Sinhalese people

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

The Sinhalese are the majority ethnic group of Sri Lanka, constituting 74% of the Sri Lankan population. They speak Sinhala, an Indo-Aryan language, and number approximately 14 million in the world.[13] They live mainly in central, south and west Sri Lanka. According to legend they are the descendants of the exiled Prince Vijaya who arrived to Sri Lanka in 5 BCE. The Sinhalese identity is based on language, heritage and religion. The vast majority of Sinhalese are Theravada Buddhists.

Etymology

The Sinhalese are also known as "Hela" or "Sinhala". These synonyms find their origins in the two words Sinha (meaning "lion") and Hela (meaning "pristine"). The name Sinhala translates to "lion people" and refers to the myths regarding the descent of the legendary founder of the Sinhalese people, the prince Vijaya. The royal dynasty from ancient times on the island was the Sinha (Lion) royal dynasty and the word Sinha finds its origins here.

History

Ancient history

The origin legend and early recorded history of the Buddhist Sinhalese is chronicled in two documents, the Mahavamsa, written in Pāli around the 4th century BC, and the much later Chulavamsa (probably penned in the 13 century CE by the Buddhist monk Dhammakitti). These are ancient sources which cover the histories of the powerful ancient kingdoms of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. The Mahavansa describes the existence of fields of rice and reservoirs, indicating a well developed agrarian society. The oral tradition of the Sinhalese people also speaks of many royal dynasties prior to the Sinha royal dynasty: Manu, Tharaka, Mahabali, Raavana, etc.

According to the Mahavamsa, the Sinhalese are descended from the exiled Prince Vijaya and his party of seven hundred followers who arrived on the island at 543 BCE. Vijaya and his followers were said to have arrived in Sri Lanka after being exiled from the city of Sinhapura in Bengal, North East India.[14] Buddhism is then said to have been introduced to the Sinhalese from India by Mahinda, son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka the Great, during the 3rd century BC.

The historical accuracy of the Mahavansa prior to the death of Ashoka is not considered to be trustworthy and so whether the story of Vijaya and Mahinda is true is debated. See Historical accuracy of the Mahavamsa.

Medieval history

During the middle ages Sri Lanka was divided into three independent kingdoms; Jaffna kingdom, Kotte kingdom and Kandyan kingdom. Parakramabahu VI was the only Sinhalese king during this time who had control of the whole island. The invasion by Magha in the 13th century lead to the establishment of the Jaffna kingdom and forced the Sinhalese to abandon their ancient centres, such as Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva, and live in the South-West of Sri Lanka. This lead to deterioration of the irrigation works in the dry zones of Sri Lanka, as the new Wet zones were ideal for cultivation. This migration was followed by a period of conflict among the Sinhalese chiefs who tried to exert political supremacy. Trade also increased during this period, as Sri Lanka began to trade Cinammon and a large number of muslim traders were bought into the island. [15]

In the 15th Century a Kandyan Kingdom formed which divided the Sinhalese politically into low-country and up-country.[15]

Modern history

The Sinhalese have a stable birth rate and a population that has been growing at a slow pace relative to India and other Asian countries.

Culture

Sinhalese culture features a wide variety of folk beliefs and rituals traditionally. Folk poems were sung by workers of various trades in the past to accompany their work and narrate the story of their lives. ideally these poems consisted of four lines and in the composition of these poems, special attention had been payed to the rhyming patterns of the poem. Buddhist festivals are dotted by unique music using traditionally Sinhala instruments. More ancient rituals like tovils (Devil exorcism) continue to enthrall audiences today and often praised and admired the good and the power of Buddha and gods in order to exorcise the demons.

Concerning popular music, Ananda Samarakoon developed the reflective and poignant Sarala gee style with his work in the late 1930s/early 1940s. He has been followed by artists of repute such as W. D. Amaradeva, Nanda Malini, Victor Ratnayake, T. M. Jayaratne, Sanath Nandasiri, Sunil Edirisinghe, Neela Wickremasinghe, Gunadasa Kapuge, Malini Bulathsinghala and Edward Jayakody.

Dramatist Ediriweera Sarachchandra revitalized the drama form with Maname in 1956. Also the same year, film director Lester James Peries created the artistic masterwork Rekava which sought to create a uniquely Sinhala cinema with artistic integrity. Since then, Peries and other directors like Vasantha Obeysekera, Dharmasena Pathiraja, Mahagama Sekera, W. A. B. de Silva, Sunil Ariyaratne, Siri Gunasinghe, G. D. L. Perera, Piyasiri Gunaratne, Titus Thotawatte, D. B. Nihalsinghe, Ranjith Lal, Dayananda Gunawardena, Mudalinayake Somaratne and Prasanna Vithanage have developed an artistic Sinhala cinema. Sinhala cinema is often made colorful by the incorporation of songs and dance adding more uniqueness to the industry.

Language

The Sinhalese speak Sinhala, also known as "Helabasa"; this language has two varieties, spoken and written. Sinhala is an Indo-Aryan language[13] brought to Sri Lanka by North East Indians who settled on the island in the fifth century.[16][17] Sinhala developed in a way different from the other Indo-Aryan languages because of the geographic separation from its Indo-Aryan sister languages. Sinhala was influenced by many languages, prominently Pali, the sacred language of Southern Buddhism, and Sanskrit. Many early Sinhala texts such as the Hela Atuwa were lost after their translation into Pali. Other significant Sinhala texts include Amāvatura, Kavu Silumina, Jathaka Potha and Sala Liheeniya. Sinhala has also borrowed words from Dravidian languages of South India and the colonial languages Portuguese, Dutch, and English.[18]

Literature

Sinhala literature dates back to antiquity with the Mahavamsa and the Culavamsa. Buddhism (which was a later development of Hinduism) did not overtake Hinduism in India, but Sri Lanka (and the Sinhalese) converted to Buddhist culture through history remaining a centre of Buddhist scholarly activities.

Folk tales like Mahadana Mutha saha Golayo and Kawate Andare continue to entertain children today. Mahadana Mutha tells the tale of a fool cum Pandit who travels around the country with his followers (Golayo) creating mischief through his ignorance. Kawate Andare tells the tale of a witty court jester and his interactions with the royal court and his son.

In the Modern period, Sinhala writers such as Martin Wickremasinghe and G. B. Senanayake have drawn widespread acclaim. Other writers of repute include Mahagama Sekera and Madewela S. Ratnayake. Martin Wickramasinghe wrote the immensely popular children's novel Madol Duwa. Munadasa Cumaratunga's Hath Pana is also widely known.

Dress

Traditionally during recreation the Sinhalese wear a sarong, (sarama in Sinhala). Men may wear a long sleeved shirt with the sarong, while women wear a tight-fitting, short-sleeved jacket with a wrap-around called the 'cheeththaya'. In the more populated areas, the Sinhalese men also wear Western-style clothing wearing suits while the women wear skirts and blouses. However for formal and ceremonial occasions women wear the traditional Kandyan (Osaria) style, which consists of a full blouse which covers the midriff completely, and is partially tucked in at the front. However, modern intermingling of styles has led to most wearers baring the midriff. The Kandyan style is considered as the national dress of Sinhalese women. In many occasions and functions, even the 'saree' plays an important role in women's clothing and has become the de facto clothing for female office workers especially in government sector. An example of its use is the Uniform of air hostesses of Sri Lankan Airlines.[18]

Religion

Most of the Sinhalese follow the Theravada school of Buddhism. In 1988 almost 93% of the sinhalese speaking population in Sri Lanka were buddhist.[19] Sinhalese Buddhists include various religious elements from Hinduism in their religious practices and ancient indigenous traditions of godlings and demons, which are native to the island.[18][20][21] Sinhalese Buddhists worship Hindu gods such as Vishnu, who has a special place in their religious practices, since he is entrusted with both protecting Buddhism in the island and the island itself. He is also recognised as bodhisattva, or "awakening being" to Sinhalese Buddhists.[20][21]

Prominent Sri Lankan anthropologists Gananath Obeyesekere and Kitsiri Malalgoda used the term "Protestant Buddhism" to describe a type of buddhism that appeared among the sinhalese in Sri Lanka as a response to Protestant Christian missionaries and their evangelical activities during the British colonial period. This kind of Buddhism involved emulating the Protestant method of converting, by the establishment of Buddhist schools and Buddhist organizations such as the Young Men's Buddhist Association. As well as printing pamphlets to encourage people to participate in debates and religious controversies to defend Buddhism.[22]

There is also a siginifiant Sinhalese Christian community, in the maritime provinces of Sri Lanka.[18] Christianity was brought to the Sinhalese by Portuguese, Dutch, and British missionary groups during their respective periods of rule.[23] Sinhalese Christians mainly follow Roman Catholicism, followed by Protestantism.[19] Their cultural centre is Negombo.

Religion is considered very important among the Sinhalese. According to a 2008 Gallup poll, 99% of Sri Lankans considered religion an important aspect of their daily lives.[24]

Education

The Sinhalese have a long history of literacy and formal learning. Instruction in basic fields like writing and reading by Buddhist Monks pre-date the birth of Christ. This traditional system followed religious rule and was meant to foster Buddhist understanding. Training of officials in such skills as keeping track of revenue and other records for administrative purposes occurred under this institution.[25]

Technical education such as the building of reservoirs and canals was passed down from generation to generation through home training and outside craft apprenticeships.[25]

The arrival of the Portuguese and Dutch and the subsequent colonization maintained religion as the center of education though in certain communities under Catholic and Presbyterian hierarchy. The British in the 1800s initially followed the same course. Following 1870 however they began a campaign for better education facilities in the region. Christian missionary groups were at the forefront of this development contributing to a high literacy among Christians.[25]

By 1901 schools in the South and the North were well tended. The inner regions lagged behind however. Also, English education facilities presented hurdles for the general populace through fees and lack of access.[25]

Geographic distribution

In Sri Lanka

Within Sri Lanka the majority of the Sinhalese reside in the south, central and western parts of the country. This districts with the largest sinhalese populations in Sri Lanka (>90%) are Hambantota, Galle, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Moneragala and Polonnaruwa.[26]

Outside Sri Lanka

As with many of the people from former colonies, Sinhalese have emigrated to several countries. There are small communities in the UK, Australia, United States and Canada with Sinhalese ancestry. In addition to this there are many Sinhalese, who reside in the above mentioned countries and countries in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Europe, temporarily in connection with empolyment and education. They are often employed as guest workers in the Middle East and professionals in the other regions.

Australia

The 2006 Census in Australia found that there were approximately 29,055 Sinhalese Australians (0.1 percent of the population). That was an addition of 8,395 Sinhalese Australians (a 40.6 percent increase) from the 2001 Census. There are 73,849 Australians (0.4 of the population) who reported having Sinhalese ancestry in 2006. This was 26 percent more in 2001, in which 58,602 Australia reported having Sinhalese ancestry. The census is counted by Sri Lankans who speak the Sinhalese language at home.

Census data released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2004 reported that Sinhalese Australians are by religion 29.7 percent Catholic; 8.0 percent Anglican, 9.9% other Christian; 46.9 percent "Other Religions" (mainly Buddhist), and 5.5 percent no religion. The Sinhalese language was also reported to be the 29th-fastest-growing language in Australia (ranking above Somali but behind Hindi and Belarusian).

Sinhalese Australians have an exceptionally low rate of return migration to Sri Lanka. In December 2001, the Department of Foreign Affairs estimated that there were 800 Australian citizens resident in Sri Lanka. It is unclear whether these were returning Sri Lankan emigrants with Australian citizenship, their Sri Lankan Australian children, or other Australians present on business or for some other reason.

Canada

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2010) |

India

There are a small amount of Sinhalese people in India, scattered all around the country, but mainly living in and around the northern and southern regions. Delhi has the largest concentration of Sinhalese people with 1,100, the states of Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra have 800 and 400 respectively. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the state of Gujarat have 200 each while other states such as Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, West Bengal, Jharkhand have populations ranging from 60 to 30 people.[27]

Italy

It is estimated that there are 30,000-33,000 Sinhalese in Italy. The major Sinhalese communities in Italy are located in Lombardia (In the districts Loreto and Lazzaretto), Milan, Lazio, Rome, Naples and Southern Italy (Particularly Palermo, Messina and Catania). Most Italian Sinhalese work as domestic workers. But they have also opened businesses such as restaurants, cleaning enterprises (eg. Cooperativa Multietnica di Pulizie Sud-Est), call centres, video-shops, traditional food shops and minimarkets.[28]

Many Sinhalese have migrated to Italy since the 1970's. Italy was attractive to the Sinhalese due to perceived easier employment opportunities and entry, compared to other European countries.[28]

In the late 70's, Sinhalese Catholic women migrated to Italy to work in elderley homes. This was followed by a wave of Sinhalese migrants who worked for Italian entrepreneurs in the early 80s. Italy was often seen as a temporary destination, but many Sinhalese decided to settle there. Many Sinhalese have also illegally migrated to Italy, mainly through the Balkans and Austria.[28]

Admission acts also encouraged more Sinhalese to migrate to Italy. For example, the Dini Decree in 1996 made it more easier for Sinhalese workers to bring their family to Italy. In Rome, Naples and Milan, the Sinhalese have built up "enlarged families", where jobs are exchanged among relatives and compatriots.[28]

The Sinhalese prefer to send their children to English speaking countries for their education and consider Italian education mediocre.[28]

The major organisation representing the Sinhalese in Italy is the Sri Lanka Association Italy. [28]

New Zealand

The early arrivals to came to New Zealand from what was then British Ceylon were a few prospectors attracted to the gold rushes. By 1874 there were a mere 33 New Zealand residents born in Ceylon.

After 1950 under the Colombo Plan some students and trainees received education in New Zealand. Up until the late 1960s the number of New Zealand residents born in Ceylon remained static. As a demand for skilled professionals in New Zealand grew it led to a noticeable increase in the number of immigrants about this time. Racial and economic tensions in Dominion of Ceylon, made worse after the declaration of the republic in 1972, also swelled immigrant numbers.[29]

In 1983 the Sri Lankan Civil War began with Sinhalese political dominance being challenged by the militant Tamil Tigers, who sought a separate Tamil state within Sri Lanka.[30] After the 1983 riots in Sri Lanka ushered in an extended civil war many Sri Lankans, both Tamil and Sinhalese, fled Sri Lanka, the number of arrivals from Sri Lanka to New Zealand and the Sri Lankan-born population in New Zealand rose dramatically.[31]

The numbers arriving continued to increase, and at the 2006 census there were over 7,000 Sri Lankans living in New Zealand.[32]

Sri Lankan New Zealanders comprised 3% of the Asian population of New Zealand in 2001. Out of the Asians, the Sri Lankans were the most likely to hold a formal qualification and to work in white-collar occupations. Sri Lankans mainly worked in health professions, business and property services, and the retail and manufacturing sectors, in large numbers. Most lived in Auckland and Wellington, with smaller populations in Waikato, Manawatū–Wanganui, Canterbury and others.[33]

United Kingdom

The main and oldest organisation representing the Sinhalese community in the UK are the UK Sinhala association.[34] The number of Sinhalese people in the UK is not known as the UK government doesn’t record statistics on language and the Sinhalese have to classify themselves as either Asian British or Asian Other.

The newspaper Lanka Viththi was created in 1997 to provide a Sinhala newspaper for the Sinhalese UK community. [35]

In 2006, a Sinhala TV channel called Kesara TV was set up in London to provide the Sinhala speaking people of the UK a TV channel in Sinhala.[36]

Some of the Sinhalese community have been against the public display of support for the LTTE in the 2009 Tamil Diaspora protests in Westminster, London.[37] Some of the Sinhalese community in the UK have faced violence from some British Sri lankan tamils over the ethnic conflict in the Sri Lankan Civil War. Several Sinhala owned Fried Chicken Shops in North London and a Sinhalese Buddhist temple in Kingsbury were vandalised in 2009.[38]

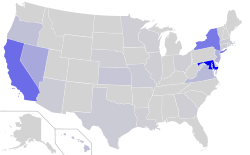

United States

The Sinhalese number about 12,000 in USA. They are mainly located in the states of California, New York, Maryland, Texas, New Jersey, Virginia, Illinois, Ohio, Florida and Massachusetts.[39]

Genetic Studies

Studies looking at the origin of the Sinhalese have been contradictory. Older studies suggest a predominantly Tamil origin followed by a significant Bengali contribution with no North Western Indian contribution.[40][41] While modern studies point towards a predominantly Bengali contribution and a minor Tamil and North Western Indian contribution.[42][43] [44]

All studies agree however, that the there is a significant relationship between the Sinhalese and the Tamil and Bengali. This is also supported by a genetic distance study, which showed low differences in genetic distance between the Sinhalese and the Tamil, Keralite and Bengali volunteers.[42]

See also

References

- ^ Department of Census and Statistics in Sri Lanka. (2001). Number and percentage of population by district and ethnic group. Available: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/PopHouSat/PDF/Population/p9p8%20Ethnicity.pdf

- ^ Nihal Jayasinghe. (2010). Letter to William Hague MP. Available: http://www.slhclondon.org/news/Letter%20to%20Mr%20William%20Hague,%20MP.pdf. Last accessed 03 May 2010.

- ^ Australian Government. (2008). Population of Australia. Available: http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/research/_pdf/poa-2008.pdf. Last accessed 03 March 2008. The People of Australia - Statistics from the 2006 Census

- ^ Italian Government. (2008). Statistiche demografiche ISTAT. Available: http://demo.istat.it/str2008/index.html. Last accessed 03 March 2009.

- ^ Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung. (2006). HISTORICAL CENSUS STATISTICS ON THE FOREIGN-BORN POPULATION OF THE UNITED STATES: 1850 TO 2000. Available: http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0081/twps0081.pdf US Census Bureau. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.ethnologue.org/show_language.asp?code=sin

- ^ Stuart Michael. (2009). A traditional Sinhalese affair. Available: http://thestar.com.my/metro/story.asp?file=/2009/11/11/central/5069773&sec=central. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/sri-lankans/3

- ^ http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/tbt/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=92333&PRID=0&PTYPE=88971,97154&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=801&Temporal=2006&THEME=80&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=

- ^ http://www.joshuaproject.net/peopctry.php?rop3=109305&rog3=IN

- ^ http://www.joshuaproject.net/countries.php?rog3=IN&sf=primarylanguagename&so=asc

- ^ http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=sin

- ^ a b Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/

- ^ Chelvadurai Manogaran (1987). Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka . United States of America: University of Hawaii Press. 20.

- ^ a b G.C. Mendis (2006). Ceylon under the British. Colombo: Asian Educational Services. 4. Medieval history

- ^ The Mahavamsa.org . (2007). The Mahavamsa - Great Chronicle - History of Sri Lanka - Mahawansa. Available: http://mahavamsa.org/. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ Asiff Hussein . (2009). Evolution of the Sinhala language. Available: http://www.lankalibrary.com/books/sinhala.htm. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d Everyculture. (2009). Sinhalese - Religion and Expressive Culture . Available: http://www.everyculture.com/South-Asia/Sinhalese-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ a b The Library of Congress. (2009). A Country Study: Sri Lanka. Available: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/lktoc.html. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ a b Buddhism transformed: religious change in Sri Lanka, by Richard Gombrich, Gananath Obeyesekere, 1999

- ^ a b Peter R. Blood. (2009). Popular Sinhalese Religion. Available: http://www.kataragama.org/docs/popular-religion.htm. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ Mahinda Deegalle. (1997). A Bibliography on Sinhala Buddhism. Available: http://www.buddhistethics.org/4/deeg1.html. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ Conversion and Demonism: Colonial Christian Discourse and Religion in Sri Lanka, David Scott, Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Apr., 1992), pp. 331-365, Published by: Cambridge University Press, Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/178949

- ^ Steve Crabtree and Brett Pelham. (2009). What Alabamians and Iranians Have in Common. Available: http://www.gallup.com/poll/114211/Alabamians-Iranians-Common.aspx. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d de Silva, K. M. (1977). Sri Lanka: A Survey. Institute of Asian Affairs, Hamburg. ISBN 0-8248-0568-2.

- ^ Sri Lankan Government. (2001). Number and percentage of population by district and ethnic group. Available: http://www.statistics.gov.lk/PopHouSat/PDF/Population/p9p8%20Ethnicity.pdf. Last accessed 03 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.joshuaproject.net/peopctry.php?rog3=IN&rop3=109305

- ^ a b c d e f Ranjith Henayaka-Lochbihler & Miriam Lambusta. (2004). The Sri Lankan Diaspora in Italy. Available: http://www.berghof-center.org/uploads/download/sri_lankan_diaspora_in_italy.pdf. Last accessed 03 April 2010.

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/sri-lankans/1

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/sri-lankans/1

- ^ http://www.nzonscreen.com/title/from-sri-lanka-with-sorrow-1996

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/sri-lankans/1

- ^ http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/sri-lankans/2

- ^ httpDr. Tilak S. Fernando . (2007). Meeting with Labour Party in London . Available: Dr. Tilak S. Fernando . Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ^ Dr. Tilak S. Fernando . (2007). TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF SINHALA NEWSPAPER IN THE U.K. . Available: http://www.infolanka.com/org/diary/219.html. Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ^ Lanka Newspapers. (2006). Sri Lankan launches Sinhala TV channel in UK . Available: http://www.lankanewspapers.com/news/2006/7/7632.html. Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ^ Walter Jayawardhana . (2009). UK SINHALA ASSOCIATION PRESIDENT TELLS MAYOR OF LONDON THAT BANNED TERRORIST GROUPS SHOULD NOT RULE LONDON STREETS. Available: http://sinhale.wordpress.com/2009/04/10/uk-sinhala-association-president-tells-mayor-of-london-that-banned-terrorist-groups-should-not-rule-london-streets/. Last accessed 28 March 2010.

- ^ http://www.thisislocallondon.co.uk/news/4394755.Sinhalese_chicken_shops_under_attack/

- ^ Joshua Project. (2010). Sinhalese of United States Ethnic People Profile. Available: http://www.joshuaproject.net/peopctry.php?rop3=109305&rog3=US. Last accessed 03 April 2010.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid8543296was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

sahawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Kirk, R. L. (1976). "The legend of Prince Vijaya — a study of Sinhalese origins". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45: 91. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450112.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mastanawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

krepwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Other references

- De Silva, K.M. History of Sri Lanka (Univ. of Calif. Press, 1981)

- Gunasekera, Tamara. Hierarchy and Egalitarianism: Caste, Class, and Power in Sinhalese Peasant Society (Athlone, 1994).

- Roberts, Michael. Sri Lanka: Collective Identities Revisited (Colombo-Marga Institute, 1997).

- Wickremeratne, Ananda. Buddhism and Ethnicity in Sri Lanka: A Historical Analysis (New Delhi-Vikas Publishing House, 1995).

External links

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

- [1]

- Department of Census and Statistics-Sri Lanka

- Ethnologue-Sinhala, a language of Sri Lanka

- CIA Factbook-Sri Lanka

- Sinhalese

- Who are the Sinhalese