Tobacco smoking

| Part of a series on |

| Smoking |

|---|

|

Tobacco smoking is the practice where tobacco is burned and the vapors either tasted or inhaled. The practice began as early as 5000–3000 BC.[1] Many civilizations burnt incense during religious rituals, which was later adopted for pleasure or as a social tool.[2] Tobacco was introduced to the Old World in the late 1500s where it followed common trade routes. The substance was met with frequent criticism, but became popular nonetheless.[3] Smoking kills one half of all smokers who don't manage to stop—as of 2007, about 4.9 million people worldwide each year.[4]

German scientists formally identified the link between smoking and lung cancer in the late 1920s leading the first anti-smoking campaign in modern history. The movement, however, failed to reach across enemy lines during the Second World War, and quickly became unpopular thereafter.[5] In 1950, health authorities again began to suggest a relationship between smoking and cancer.[6] Scientific evidence mounted in the 1980s, which prompted political action against the practice. Rates of consumption from 1965 onward in the developed world have either peaked or declined.[7] However, they continue to climb in the developing world.[8]

Smoking is the most common method of consuming tobacco, and tobacco is the most common substance smoked. The agricultural product is often mixed with other additives[9] and then pyrolyzed. The resulting vapors are then inhaled and the active substances absorbed through the alveoli in the lungs.[10] The active substances trigger chemical reactions in nerve endings which heightens heart rate, memory, alertness,[11] and reaction time.[12] Dopamine and later endorphins are released, which are often associated with pleasure.[13] As of 2000, smoking is practiced by some 1.22 billion people. Men are more likely to smoke than women,[14] though the gender gap declines with younger age.[15][16] The poor are more likely to smoke than the wealthy, and people of developing countries than those of developed countries.[8]

Many smokers begin during adolescence or early adulthood. Usually during the early stages, smoking provides pleasurable sensations, serving as a source of positive reinforcement. After an individual has smoked for many years, the avoidance of withdrawal symptoms and negative reinforcement become the key motivations to continue.

History

Early use

The history of smoking dates back to as early as 5000–3000 BC when the agricultural product began to be cultivated in South America; consumption later evolved into burning the plant substance either by accident or with intent of exploring other means of consumption.[1] The practice worked its way into shamanistic rituals.[17][page needed] Many ancient civilizations, such as the Babylonians, Indians and Chinese, burnt incense as a part of religious rituals, as did the Israelites and the later Catholic and Orthodox Christian churches. Smoking in the Americas probably had its origins in the incense-burning ceremonies of shamans but was later adopted for pleasure or as a social tool.[2] The smoking of tobacco and various hallucinogenic drugs was used to achieve trances and to come into contact with the spirit world.

Eastern North American tribes would carry large amounts of tobacco in pouches as a readily accepted trade item and would often smoke it in pipes, either in defined ceremonies that were considered sacred, or to seal a bargain,[18] and they would smoke it at such occasions in all stages of life, even in childhood.[19][page needed] It was believed that tobacco was a gift from the Creator and that the exhaled tobacco smoke was capable of carrying one's thoughts and prayers to heaven.[20]

Apart from smoking, tobacco had a number of uses as medicine. As a pain killer it was used for earache and toothache and occasionally as a poultice. Smoking was said by the desert Indians to be a cure for colds, especially if the tobacco was mixed with the leaves of the small Desert Sage, Salvia Dorrii, or the root of Indian Balsam or Cough Root, Leptotaenia multifida, the addition of which was thought to be particularly good for asthma and tuberculosis.[21]

Popularization

In 1612, six years after the settlement of Jamestown, John Rolfe was credited as the first settler to successfully raise tobacco as a cash crop. The demand quickly grew as tobacco, referred to as "brown gold", reviving the Virginia join stock company from its failed gold expeditions.[22] In order to meet demands from the old world, tobacco was grown in succession, quickly depleting the soil. This became a motivator to settle west into the unknown continent, and likewise an expansion of tobacco production.[23] Indentured servitude became the primary labor force up until Bacon's Rebellion, from which the focus turned to slavery.[24] This trend abated following the American revolution as slavery became regarded as unprofitable. However, the practice was revived in 1794 with the invention of the cotton gin.[25][page needed]

Frenchman Jean Nicot (from whose name the word nicotine is derived) introduced tobacco to France in 1560, and tobacco then spread to England. The first report of a smoking Englishman is of a sailor in Bristol in 1556, seen "emitting smoke from his nostrils".[3] Like tea, coffee and opium, tobacco was just one of many intoxicants that was originally used as a form of medicine.[26] Tobacco was introduced around 1600 by French merchants in what today is modern-day Gambia and Senegal. At the same time caravans from Morocco brought tobacco to the areas around Timbuktu and the Portuguese brought the commodity (and the plant) to southern Africa, establishing the popularity of tobacco throughout all of Africa by the 1650s.

Soon after its introduction to the Old World, tobacco came under frequent criticism from state and religious leaders. Murad IV, sultan of the Ottoman Empire 1623-40 was among the first to attempt a smoking ban by claiming it was a threat to public moral and health. The Chinese emperor Chongzhen issued an edict banning smoking two years before his death and the overthrow of the Ming dynasty. Later, the Manchu of the Qing dynasty, who were originally a tribe of nomadic horse warriors, would proclaim smoking "a more heinous crime than that even of neglecting archery". In Edo period Japan, some of the earliest tobacco plantations were scorned by the shogunate as being a threat to the military economy by letting valuable farmland go to waste for the use of a recreational drug instead of being used to plant food crops.[27]

Religious leaders have often been prominent among those who considered smoking immoral or outright blasphemous. In 1634 the Patriarch of Moscow forbade the sale of tobacco and sentenced men and women who flaunted the ban to have their nostrils slit and their backs whipped until skin came off their backs. The Western church leader Urban VII likewise condemned smoking in a papal bull of 1642. Despite many concerted efforts, restrictions and bans were almost universally ignored. When James I of England, a staunch anti-smoker and the author of a A Counterblaste to Tobacco, tried to curb the new trend by enforcing a 4000% tax increase on tobacco in 1604, it proved a failure, as London had some 7,000 tobacco sellers by the early 1600s. Later, scrupulous rulers would realise the futility of smoking bans and instead turned tobacco trade and cultivation into lucrative government monopolies.[28][29]

By the mid-1600s every major civilization had been introduced to tobacco smoking and in many cases had already assimilated it into the native culture, despite the attempts of many rulers to eliminate the practice with harsh penalties or fines. Tobacco, both product and plant, followed the major trade routes to major ports and markets, and then on into the hinterlands. The English language term smoking was coined in the late 1700s; before then the practice was called drinking smoke.[3][page needed]

Growth remained stable until the American Civil War in 1860s, when the primary labor force shifted from slavery to share cropping. This, along with a change in demand, lead to the industrialization of tobacco production with the cigarette. James Bonsack, a craftsman, in 1881 produce a machine to speed the production in cigarettes.[30]

Social stigma

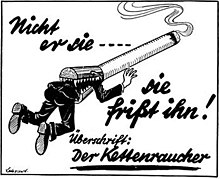

In Germany, anti-smoking groups, often associated with anti-liquor groups,[31] first published advocacy against the consumption of tobacco in the journal Der Tabakgegner (The Tobacco Opponent) in 1912 and 1932. In 1929, Fritz Lickint of Dresden, Germany, published a paper containing formal statistical evidence of a lung cancer–tobacco link. During the Great depression Adolf Hitler condemned his earlier smoking habit as a waste of money,[32] and later with stronger assertions. This movement was further strengthened with Nazi reproductive policy as women who smoked were viewed as unsuitable to be wives and mothers in a German family.[33]

The anti-tobacco movement in Nazi Germany did not reach across enemy lines during the Second World War, as anti-smoking groups quickly lost popular support. By the end of the Second World War, American cigarette manufactures quickly reentered the German black market. Illegal smuggling of tobacco became prevalent,[34] and leaders of the Nazi anti-smoking campaign were silenced.[35] As part of the Marshall Plan, the United States shipped free tobacco to Germany; with 24,000 tons in 1948 and 69,000 tons in 1949.[34] Per capita yearly cigarette consumption in post-war Germany steadily rose from 460 in 1950 to 1,523 in 1963.[5] By the end of the 1900s, anti-smoking campaigns in Germany was unable to exceed the effectiveness of the Nazi-era climax in the years 1939–41 and German tobacco health research was described by Robert N. Proctor as "muted".[5]

Richard Doll in 1950 published research in the British Medical Journal showing a close link between smoking and lung cancer.[36] Four years later, in 1954 the British Doctors Study, a study of some 40 thousand doctors over 20 years, confirmed the suggestion, based on which the government issued advice that smoking and lung cancer rates were related.[6] In 1964 the United States Surgeon General's Report on Smoking and Health likewise began suggesting the relationship between smoking and cancer.

As scientific evidence mounted in the 1980s, tobacco companies claimed contributory negligence as the adverse health effects were previously unknown or lacked substantial credibility. Health authorities sided with these claims up until 1998, from which they reversed their position. The Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, originally between the four largest US tobacco companies and the Attorneys General of 46 states, restricted certain types of tobacco advertisement and required payments for health compensation; which later amounted to the largest civil settlement in United States history.[37]

From 1965 to 2006, rates of smoking in the United States declined from 42% to 20.8%.[7] The majority of those who quit were professional, affluent men. Although the per-capita number of smokers decreased, the average number of cigarettes consumed per person per day increased from 22 in 1954 to 30 in 1978. This paradoxical event suggests that those who quit smoked less, while those who continued to smoke moved to smoke more light cigarettes.[38] Trend has been paralleled by many industrialized nations as rates have either leveled-off or declined. In the developing world, however, tobacco consumption continues to rise at 3.4% in 2002.[8] In Africa, smoking is in most areas considered to be modern, and many of the strong adverse opinions that prevail in the West receive much less attention.[39] Today Russia leads as the top consumer of tobacco followed by Indonesia, Laos, Ukraine, Belarus, Greece, Jordan, and China.[40]

Consumption

Methods

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the fresh leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. The genus contains a number of species, however, Nicotiana tabacum is the commonly grown. Nicotiana rustica follows as second containing higher concentrations of nicotine. These leaves are harvested and cured to allow for the slow oxidation and degradation of carotenoids in tobacco leaf. This produces certain compounds in the tobacco leaves which can be attributed to sweet hay, tea, rose oil, or fruity aromatic flavors. Before packaging, the tobacco is often combined with other additives in order to: enhance the addictive potency, shift the products pH, or improve the effects of smoke by making it more palatable. In the United States these additives are regulated to 599 substances.[9] The product is then processed, packaged, and shipped to consumer markets. Means of consumption has greatly expanded in scope as new methods of delivering the active substances with fewer by-products have encompassed or are beginning to encompass:

- Beedi

- Bidis smoke produce higher levels of carbon monoxide, nicotine, and tar than cigarettes typical in the United States.[41][42]

- Cigars

- Cigars are tightly rolled bundles of dried and fermented tobacco which are ignited so that smoke may be drawn into the smoker's mouth. They are generally not inhaled because the high alkalinity of the smoke, which can quickly become irritating to the trachea and lungs. The prevalence of cigar smoking varies depending on location, historical period, and population surveyed, and prevalence estimates vary somewhat depending on the survey method. The United States is the top consuming country by far, followed by Germany and the United Kingdom; the US and Western Europe account for about 75% of cigar sales worldwide.[43] As of 2005 it is estimated that 4.3% of men and 0.3% of women smoke cigars.[44]

- Cigarettes

- Cigarettes, French for "small cigar", are a product consumed through smoking and manufactured out of cured and finely cut tobacco leaves and reconstituted tobacco, often combined with other additives, which are then rolled or stuffed into a paper-wrapped cylinder.[9] Cigarettes are ignited and inhaled, usually through a cellulose acetate filter, into the mouth and lungs.

- Electronic cigarette

- Electronic cigarettes is an alternative to tobacco smoking, although no tobacco is consumed. It is a battery-powered device that provides inhaled doses of nicotine by delivering a vaporized propylene glycol/nicotine solution. Many legislation and public health investigations are currently pending in many countries due to its relatively recent emergence.

- Hookah

- Hookah are a single or multi-stemmed (often glass-based) water pipe for smoking. Originally from India, the hookah has gained immense popularity, especially in the Middle East. A hookah operates by water filtration and indirect heat. It can be used for smoking herbal fruits, tobacco, or cannabis.

- Kreteks

- Kreteks are cigarettes made with a complex blend of tobacco, cloves and a flavoring "sauce". It was first introduced in the 1880s in Kudus, Java, to deliver the medicinal eugenol of cloves to the lungs. The quality and variety of tobacco play an important role in kretek production, from which kreteks can contain more than 30 types of tobacco. Minced dried clove buds weighing about 1/3 of the tobacco blend are added to add flavoring. In 2004 the United States prohibited cigarettes from having a "characterizing flavor" of certain ingredients other than tobacco and menthol, thereby removing Kreteks from being classified as cigarettes.[45]

- Passive smoking

- Passive smoking is the involuntary consumption of smoked tobacco. Second-hand smoke (SHS) is the consumption where the burning end is present, environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) or third-hand smoke is the consumption of the smoke that remains after the burning end has been extinguished. Because of its negative implications, this form of consumption has played a central role in the regulation of tobacco products.

- Pipe smoking

- Pipe smoking typically consists of a small chamber (the bowl) for the combustion of the tobacco to be smoked and a thin stem (shank) that ends in a mouthpiece (the bit). Shredded pieces of tobacco are placed into the chamber and ignited. Tobaccos for smoking in pipes are often carefully treated and blended to achieve flavour nuances not available in other tobacco products.

- Roll-Your-Own

- Roll-Your-Own or hand-rolled cigarettes, often called 'rollies', are very popular particularly in European countries. These are prepared from loose tobacco, cigarette papers and filters all bought separately. They are usually much cheaper to make.

- Vaporizer

- A vaporizer is a device used to sublimate the active ingredients of plant material. Rather than burning the herb, which produces potentially irritating, toxic, or carcinogenic by-products; a vaporizer heats the material in a partial vacuum so that the active compounds contained in the plant boil off into a vapor. Medical administration of a smoke substance often prefer this method as to directly pyrolyzing the plant material.

Physiology

The active substances in tobacco, especially cigarettes, is administered by burning the leaves and inhaling the vaporized gas that results. This quickly and effectively delivers substances into the bloodstream by absorption through the alveoli in the lungs. The lungs contain some 300 million alveoli, which amounts to a surface area of over 70 m2 (about the size of a tennis court). This method is inefficient as not all of the smoke will be inhaled, and some amount of the active substances will be lost in the process of combustion, pyrolysis.[10] Pipe and Cigar smoke are not inhaled because of its high alkalinity, which are irritating to the trachea and lungs. However, because of its higher alkalinity (pH 8.5) compared to cigarette smoke (pH 5.3), unionized nicotine is more readily absorbed through the mucous membranes in the mouth.[46] Nicotine absorption from cigar and pipe, however, is much less than that from cigarette smoke.[47]

The inhaled substances trigger chemical reactions in nerve endings. The cholinergic receptors are often triggered by the naturally occurring neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Acetylcholine and Nicotine express chemical similarities, which allows Nicotine to trigger the receptor as well.[48] These nicotinic acetylcholine receptors takes are located in the central nervous system and at the nerve-muscle junction of skeletal muscles; whose activity increases heart rate, alertness,[11] and faster reaction times.[12] Nicotine acetylcholine stimulation is not directly addictive. However, since dopamine-releasing neurons are abundant on nicotine receptors, dopamine is released.[49] This release of dopamine, which is associated with pleasure, is reinforcing and may also increase working memory.[13][50] Nicotine and cocaine activate similar patterns of neurons, which supports the idea that common substrates among these drugs.[51]

When tobacco is smoked, most of the nicotine is pyrolyzed. However, a dose sufficient to cause mild somatic dependency and mild to strong psychological dependency remains. There is also a formation of harmane (a MAO inhibitor) from the acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke. This seems to play an important role in nicotine addiction—probably by facilitating a dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens as a response to nicotine stimuli.[52] Using rat studies, repeated exposure after nicotine use in in less responsive the nucleus accumbens cells responsible for reinforcement, which implicates that many events, not just nicotine itself, likewise become less reinforcing.[53]

Demographics

As of 2000, smoking is practiced by 1.22 billion people. Assuming no change in prevalence it is predicted that 1.45 billion people will smoke in 2010 and 1.5 to 1.9 billion in 2025. Assuming that prevalence will decrease at 1% a year and that there will be a modest increase of income of 2%, it is predicted the number of smokers will stand at 1.3 billion in 2010 and 2025.[14]

Smoking is generally five times higher among men than women,[14] however the gender gap declines with younger age.[15][16] In developed countries smoking rates for men have peaked and have begun to decline, however for women they continue to climb.[54]

As of 2002, about twenty percent of young teens (13–15) smoke worldwide. From which 80,000 to 100,000 children begin smoking every day—roughly half of which live in Asia. Half of those who begin smoking in adolescent years are projected to go on to smoke for 15 to 20 years.[8]

The World Health Organization (WHO) states that "Much of the disease burden and premature mortality attributable to tobacco use disproportionately affect the poor". Of the 1.22 billion smokers, 1 billion of them live in developing or transitional economies. Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world.[55] In the developing world, however, tobacco consumption is rising by 3.4% per year as of 2002.[8]

The WHO in 2004 projected 58.8 million deaths to occur globally,[56] from which 5.4 million are tobacco-attributed,[57] and 4.9 million as of 2007.[58] As of 2002, 70% of the deaths are in developing countries.[58]

Psychology

Takeup

Most smokers begin during adolescence or early adulthood. Smoking has elements of risk-taking and rebellion, which often appeal to young people. The presence of high-status models and peers may also encourage smoking. Because teenagers are influenced more by their peers than by adults, attempts by parents, schools, and health professionals at preventing people from trying cigarettes are often unsuccessful.[60][61]

Children of smoking parents are more likely to smoke than children with non-smoking parents. One study found that parental smoking cessation was associated with less adolescent smoking, except when the other parent currently smoked.[62] A current study tested the relation of adolescent smoking to rules regulating where adults are allowed to smoke in the home. Results showed that restrictive home smoking policies were associated with lower likelihood of trying smoking for both middle and high school students.[63]

Many anti-smoking organizations claim that teenagers begin their smoking habits due to peer pressure, and cultural influence portrayed by friends. However, one study found that direct pressure to smoke cigarettes did not play a significant part in adolescent smoking. In that study, adolescents also reported low levels of both normative and direct pressure to smoke cigarettes.[64] A similar study showed that individuals play a more active role in starting to smoke than has previously been acknowledged and that social processes other than peer pressure need to be taken into account.[65] Another study's results revealed that peer pressure was significantly associated with smoking behavior across all age and gender cohorts, but that intrapersonal factors were significantly more important to the smoking behavior of 12–13 year-old girls than same-age boys. Within the 14–15 year-old age group, one peer pressure variable emerged as a significantly more important predictor of girls' than boys' smoking.[66] It is debated whether peer pressure or self-selection is a greater cause of adolescent smoking.

Psychologists such as Hans Eysenck have developed a personality profile for the typical smoker. Extraversion is the trait that is most associated with smoking, and smokers tend to be sociable, impulsive, risk taking, and excitement seeking individuals.[67] Although, personality and social factors may make people likely to smoke, the actual habit is a function of operant conditioning. During the early stages, smoking provides pleasurable sensations (because of its action on the dopamine system) and thus serves as a source of positive reinforcement.

Persistence

Because they are engaging in an activity that has negative effects on health, people who smoke tend to rationalize their behavior. In other words, they develop convincing, if not necessarily logical reasons why smoking is acceptable for them to do. For example, a smoker could justify his or her behavior by concluding that everyone dies and so cigarettes do not actually change anything. Or a person could believe that smoking relieves stress or has other benefits that justify its risks.

The reasons given by smokers for this activity are broadly categorized as addictive smoking, pleasure from smoking, tension reduction/relaxation, social smoking, stimulation, habit/automatism, and handling. There are gender differences in how much each of these reasons contribute, with females more likely than males to cite tension reduction/relaxation, stimulation and social smoking.[68]

Some smokers argue that the depressant effect of smoking allows them to calm their nerves, often allowing for increased concentration. However, according to the Imperial College London, "Nicotine seems to provide both a stimulant and a depressant effect, and it is likely that the effect it has at any time is determined by the mood of the user, the environment and the circumstances of use. Studies have suggested that low doses have a depressant effect, while higher doses have stimulant effect."[69]

The lack of deterrence by the deleterious health effects is a prototypical example of optimism bias.

Patterns

A number of studies have established that cigarette sales and smoking follow distinct time-related patterns. For example, cigarette sales in the United States of America have been shown to follow a strongly seasonal pattern, with the high months being the months of summer, and the low months being the winter months.[70]

Similarly, smoking has been shown to follow distinct circadian patterns during the waking day—with the high point usually occurring shortly after waking in the morning, and shortly before going to sleep at night.[71]

Impact

Economic

In countries where there is a public health system, society covers the cost of medical care for smokers who become ill through in the form of increased taxes. Two arguments exist on this front, the "pro-smoking" argument suggesting that heavy smokers generally don't live long enough to develop the costly and chronic illnesses which affect the elderly, reducing society's healthcare burden. The "anti-smoking" argument suggests that the healthcare burden is increased because smokers get chronic illnesses younger and at a higher rate than the general population.

Data on both positions is limited. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published research in 2002 claiming that the cost of each pack of cigarettes sold in the United States was more than $7 in medical care and lost productivity.[72] The cost may be higher, with another study putting it as high as $41 per pack, most of which however is on the individual and his/her family.[73] This is how one author of that study puts it when he explains the very low cost for others: "The reason the number is low is that for private pensions, Social Security, and Medicare — the biggest factors in calculating costs to society — smoking actually saves money. Smokers die at a younger age and don't draw on the funds they've paid into those systems."[73]

By contrast, some non-scientific studies, including one conducted by Philip Morris in the Czech Republic[74] and another by the Cato Institute,[75] support the opposite position. Philip Morris has explicitly apologised for the former study, saying: "The funding and public release of this study which, among other things, detailed purported cost savings to the Czech Republic due to premature deaths of smokers, exhibited terrible judgment as well as a complete and unacceptable disregard of basic human values. For one of our tobacco companies to commission this study was not just a terrible mistake, it was wrong. All of us at Philip Morris, no matter where we work, are extremely sorry for this. No one benefits from the very real, serious and significant diseases caused by smoking."[74]

Between 1970 an 1995, per-capita cigarette consumption in poorer developing countries increased by 67 percent, while it dropped by 10 percent in the richer developed world. Eighty percent of smokers now live in less developed countries. By 2030, the World Health Organization (WHO) forecasts that 10 million people a year will die of smoking-related illness, making it the single biggest cause of death worldwide, with the largest increase to be among women. WHO forecasts' the 21st century's death rate from smoking to be ten times the 20th century's rate. ("Washingtonian" magazine, December 2007).

Health

Tobacco use leads most commonly to diseases affecting the heart and lungs, with smoking being a major risk factor for heart attacks, strokes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and cancer (particularly lung cancer, cancers of the larynx and mouth, and pancreatic cancer).

The World Health Organization estimate that tobacco caused 5.4 million deaths in 2004[77] and 100 million deaths over the course of the 20th century.[78] Similarly, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes tobacco use as "the single most important preventable risk to human health in developed countries and an important cause of premature death worldwide."[79]

Rates of smoking have leveled off or declined in the developed world. Smoking rates in the United States have dropped by half from 1965 to 2006 falling from 42% to 20.8% in adults.[80] In the developing world, tobacco consumption is rising by 3.4% per year.[81]

Social

Famous smokers of the past used cigarettes or pipes as part of their image, such as Jean Paul Sartre's Gauloise-brand cigarettes; Albert Einstein's, Joseph Stalin's, Douglas MacArthur's, Bertrand Russell's, and Bing Crosby's pipes; or the news broadcaster Edward R. Murrow's cigarette. Writers in particular seemed to be known for smoking; see, for example, Cornell Professor Richard Klein's book Cigarettes are Sublime for the analysis, by this professor of French literature, of the role smoking plays in 19th and 20th century letters. The popular author Kurt Vonnegut addressed his addiction to cigarettes within his novels. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson was well known for smoking a pipe in public as was Winston Churchill for his cigars. Sherlock Holmes, the fictional detective created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle smoked a pipe, cigarettes, and cigars, besides injecting himself with cocaine, "to keep his overactive brain occupied during the dull London days, when nothing happened". The DC Vertigo comic book character, John Constantine, created by Alan Moore, is synonymous with smoking, so much so that the first storyline by Preacher creator, Garth Ennis, centered around John Constantine contracting lung cancer. Professional wrestler James Fullington, while in character as "The Sandman", is a chronic smoker in order to appear "tough".

The ceremonial smoking of tobacco, and praying with a sacred pipe, is a prominent part of the religious ceremonies of a number of Native American Nations. Sema, the Anishinaabe word for tobacco, is grown for ceremonial use and considered the ultimate sacred plant since its smoke was believed to carry prayers to the heavens. In most major religions, however, tobacco smoking is not specifically prohibited, although it may be discouraged as an immoral habit. Before the health risks of smoking were identified through controlled study, smoking was considered an immoral habit by certain Christian preachers and social reformers. The founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, Jr, recorded that on February 27, 1833, he received a revelation which discouraged tobacco use. This "Word of Wisdom" was later accepted as a commandment, and faithful Latter-day Saints abstain completely from tobacco.[82] Jehovah's Witnesses base their stand against smoking on the Bible's command to "clean ourselves of every defilement of flesh" (2 Corinthians 7:1). The Jewish Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan (1838–1933) was one of the first Jewish authorities to speak out on smoking. In the Bahá'í Faith, smoking tobacco is discouraged though not forbidden.[83]

Public policy

On February 27, 2005 the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, took effect. The FCTC is the world's first public health treaty. Countries that sign on as parties agree to a set of common goals, minimum standards for tobacco control policy, and to cooperate in dealing with cross-border challenges such as cigarette smuggling. Currently the WHO declares that 4 billion people will be covered by the treaty, which includes 168 signatories.[84] Among other steps, signatories are to put together legislation that will eliminate secondhand smoke in indoor workplaces, public transport, indoor public places and, as appropriate, other public places.

Taxation

Many governments have introduced excise taxes on cigarettes in order to reduce the consumption of cigarettes.

In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said that each pack of cigarettes sold in the United States costs the nation more than $7 in medical care and lost productivity,[72] over $2000 per year per smoker. Another study by a team of health economists finds the combined price paid by their families and society is about $41 per pack of cigarettes.[85]

Substantial scientific evidence shows that higher cigarette prices result in lower overall cigarette consumption. Most studies indicate that a 10% increase in price will reduce overall cigarette consumption by 3% to 5%. Youth, minorities, and low-income smokers are two to three times more likely to quit or smoke less than other smokers in response to price increases.[86][87] Smoking is often cited as an example of an inelastic good, however, i.e. a large rise in price will only result in a small decrease in consumption.

Many nations have implemented some form of tobacco taxation. As of 1997, Denmark had the highest cigarette tax burden of $4.02 per pack. Taiwan only had a tax burden of $0.62 per pack. Currently, the average price and excise tax on cigarettes in the United States is well below those in many other industrialized nations.[88]

Cigarette taxes vary widely from state to state in the United States. For example, South Carolina has a cigarette tax of only 7 cents per pack, the nation's lowest, while Rhode Island has the highest cigarette tax in the U.S.: $3.46 per pack. In Alabama, Illinois, Missouri, New York City, Tennessee, and Virginia, counties and cities may impose an additional limited tax on the price of cigarettes.[89]

In the United Kingdom, a packet of 20 cigarettes typically costs between £4.25 and £5.50 depending on the brand purchased and where the purchase was made.[90] The UK has a strong black market for cigarettes which has formed as a result of the high taxation, and it is estimated 27% of cigarette and 68% of handrolling tobacco consumption was non-UK duty paid (NUKDP).[91]

In Australia total taxes account for 62.5% of the final price of a packet of cigarettes (2007 figures). These taxes include federal excise or customs duty, and the more recently introduced Goods and Services Tax (GST). [92]

Restrictions

In June 1967, the Federal Communications Commission ruled that programs broadcast on a television station that discussed smoking and health were insufficient to offset the effects of paid advertisements that were broadcast for five to ten minutes each day. In April 1970, Congress passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act banning the advertising of cigarettes on television and radio starting on January 2, 1971.[93]

The Tobacco Advertising Prohibition Act 1992 expressly prohibited almost all forms of Tobacco advertising in Australia, including the sponsorship of sporting or other cultural events by cigarette brands.

All tobacco advertising and sponsorship on television has been banned within the European Union since 1991 under the Television Without Frontiers Directive (1989)[94] This ban was extended by the Tobacco Advertising Directive, which took effect in July 2005 to cover other forms of media such as the internet, print media, and radio. The directive does not include advertising in cinemas and on billboards or using merchandising – or tobacco sponsorship of cultural and sporting events which are purely local, with participants coming from only one Member State[95] as these fall outside the jurisdiction of the European Commission. However, most member states have transposed the directive with national laws that are wider in scope than the directive and cover local advertising. A 2008 European Commission report concluded that the directive had been successfully transposed into national law in all EU member states, and that these laws were well implemented.[96]

Some countries also impose legal requirements on the packaging of tobacco products. For example in the countries of the European Union, Turkey, Australia[97] and South Africa, cigarette packs must be prominently labeled with the health risks associated with smoking.[98] Canada, Australia, Thailand, Iceland and Brazil have also imposed labels upon cigarette packs warning smokers of the effects, and they include graphic images of the potential health effects of smoking. Cards are also inserted into cigarette packs in Canada. There are sixteen of them, and only one comes in a pack. They explain different methods of quitting smoking. Also, in the United Kingdom, there have been a number of graphic NHS advertisements, one showing a cigarette filled with fatty deposits, as if the cigarette is symbolising the artery of a smoker.

Many countries have a smoking age, In many countries, including the United States, most European Union member states, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Israel, India, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Australia, it is illegal to sell tobacco products to minors and in the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Denmark and South Africa it is illegal to sell tobacco products to people under the age of 16. On September 1, 2007 the minimum age to buy tobacco products in Germany rose from 16 to 18, as well as in Great Britain where on October 1, 2007 it rose from 16 to 18.[99] Underlying such laws is the belief that people should make an informed decision regarding the risks of tobacco use. These laws have a lax enforcement in some nations and states. In China, Turkey, and many other countries usually a child will have little problem buying tobacco products, because they are often told to go to the store to buy tobacco for their parents.

Several countries such as Ireland, Latvia, Estonia, the Netherlands, France, Finland, Norway, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Portugal, Singapore, Italy, Indonesia, India, Lithuania, Chile, Spain, Iceland, United Kingdom, Slovenia and Malta have legislated against smoking in public places, often including bars and restaurants. Restaurateurs have been permitted in some jurisdictions to build designated smoking areas (or to prohibit smoking). In the United States, many states prohibit smoking in restaurants, and some also prohibit smoking in bars. In provinces of Canada, smoking is illegal in indoor workplaces and public places, including bars and restaurants. As of March 31, 2008 Canada has introduced a smoking ban in all public places, as well as within 10 meters of an entrance to any public place. In Australia, smoking bans vary from state to state. Currently, Queensland has total bans within all public interiors (including workplaces, bars, pubs and eateries) as well as patrolled beaches and some outdoor public areas. There are, however, exceptions for designated smoking areas. In Victoria, smoking is banned in train stations, bus stops and tram stops as these are public locations where second hand smoke can affect non-smokers waiting for public transport, and since July 1, 2007 is now extended to all indoor public places. In New Zealand and Brazil, smoking is banned in enclosed public places mainly bars, restaurants and pubs. Hong Kong banned smoking on January 1, 2007 in the workplace, public spaces such as restaurants, karaoke rooms, buildings, and public parks. Bars serving alcohol who do not admit minors were exempt until 2009. In Romania smoking is illegal in trains, metro stations, public institutions (except where designated, usually outside) and public transportation.

Product safety

An indirect public health problem posed by cigarettes is that of accidental fires, usually linked with consumption of alcohol. Numerous cigarette designs have been proposed, some by tobacco companies themselves, which would extinguish a cigarette left unattended for more than a minute or two, thereby reducing the risk of fire. Among American tobacco companies, some have resisted this idea, while others have embraced it. RJ Reynolds was a leader in making prototypes of these cigarettes in 1983[100] and will make all of their U.S. market cigarettes to be fire-safe by 2010.[101] Phillip Morris is not in active support of it.[102] Lorillard, the nation's third largest tobacco company, seems to be ambivalent.[102]

Gateway drug theory

The relationship between tobacco and other drug use has been well-established, however the nature of this association remains unclear. The two main theories are the phenotypic causation (gateway) model and the correlated liabilities model. The causation model argues that smoking is a primary influence on future drug use,[103] while the correlated liabilities model argues that smoking and other drug use are predicated on genetic or environmental factors.[104]

Cessation

Smoking cessation, referred to as "quitting" is the action leading towards abstinence of tobacco smoking. There are a number of methods such as cold turkey, nicotine replacement therapy, antidepressants, hypnosis, self-help, and support groups.

References

- ^ a b Gately, Iain (2004) [2003]. Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Diane. pp. 3–7. ISBN 0-80213-960-4. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Robicsek, Francis (1979). "The Smoking Gods: Tobacco in Maya Art, History, and Religion" (Document). University of Oklahoma Press. p. 30.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Lloyd, John; Mitchinson, John (2008-07-25). "The Book of General Ignorance" (Document). Harmony Books.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help) - ^ West, Robert and Shiffman, Saul (2007). Fast Facts: Smoking Cessation. Health Press Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-903734-98-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Proctor 2000, p. 228

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1529, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1529instead. - ^ a b VJ Rock, MPH, A Malarcher, PhD, JW Kahende, PhD, K Asman, MSPH, C Husten, MD, R Caraballo, PhD (2007-11-09). "Cigarette Smoking Among Adults --- United States, 2006". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

In 2006, an estimated 20.8% (45.3 million) of U.S. adults[...]

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "WHO/WPRO-Smoking Statistics". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2002-05-28. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ^ a b c Wingand, Jeffrey S. (2006). "ADDITIVES, CIGARETTE DESIGN and TOBACCO PRODUCT REGULATION" (PDF). Mt. Pleasant, MI 48804: Jeffrey Wigand. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Gilman & Xun 2004, p. 318

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/BF00442260, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/BF00442260instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s002130050553, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s002130050553instead. - ^ a b Gilman & Xun 2004, pp. 320–321

- ^ a b c Guindon, G. Emmanuel; Boisclair, David (2003). "Past, current and future trends in tobacco use" (Document). Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. pp. 13–16.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b The World Health Organization, and the Institute for Global Tobacco Control, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health (2001). "Women and the Tobacco Epidemic: Challenges for the 21st Century" (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Surgeon General's Report—Women and Smoking". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2001. p. 47. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ^ Wilbert, Johannes (1993-07-28). "Tobacco and Shamanism in South America" (Document). Yale University Press.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Heckewelder, John Gottlieb Ernestus; Reichel, William Cornelius (1971) [1876]. "History, manners, and customs of the Indian nations who once inhabited Pennsylvania and the neighbouring states" (Document). The Historical society of Pennsylvania. p. 149.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|format=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Diéreville; Webster, John Clarence; Webster, Alice de Kessler Lusk (1933). "Relation of the voyage to Port Royal in Acadia or New France" (Document). The Champlain Society.

They smoke with excessive eagerness […] men, women, girls and boys, all find their keenest pleasure in this way

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help) - ^ Gottsegen, Jack Jacob (1940). "Tobacco: A Study of Its Consumption in the United States" (Document). Pitman Publishing Company. p. 107.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Balls, Edward K. (1962-10-01). "Early Uses of California Plants" (Document). University of California Press. pp. 81–85.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Jordan, Jr., Ervin L. "Jamestown, Virginia, 1607-1907: An Overview" (Document). University of Virginia.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Kulikoff, Allan (1986-08-01). "Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake" (Document). The University of North Carolina Press.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Cooper, William James (2000). "Liberty and Slavery: Southern Politics to 1860" (Document). Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 9.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Trager, James (1994). "The People's Chronology: A Year-by-year Record of Human Events from Prehistory to the Present" (Document). Holt.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gilman & Xun 2004, p. 38

- ^ Gilman & Xun 2004, pp. 92–99

- ^ Gilman & Xun 2004, pp. 15–16

- ^ "A Counterblaste to Tobacco" (Document). University of Texas at Austin. 2002-04-16 [1604].

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Burns, Eric (2006-09-28). "The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco" (Document). Temple University Press. pp. 134–135.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Proctor 2000, p. 178

- ^ Proctor 2000, p. 219

- ^ Proctor 2000, p. 187

- ^ a b Proctor 2000, p. 245

- ^ Proctor, Robert N. (1996). "Nazi Medicine and Public Health Policy" (Document). Dimensions, Anti-Defamation League.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14772469, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14772469instead. - ^ Milo Geyelin (November 23, 1998). "Forty-Six States Agree to Accept $206 Billion Tobacco Settlement". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Hilton, Matthew (2000-05-04). "Smoking in British Popular Culture, 1800-2000: Perfect Pleasures" (Document). Manchester University Press. pp. 229–241.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Gilman & Xun 2004, pp. 46–57

- ^ a b MPOWER 2008, pp. 267–288

- ^ "Bidi Use Among Urban Youth – Massachusetts, March-April 1999". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999-09-17. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9862656, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9862656instead. - ^ Rarick CA (2008-04-02). "Note on the premium cigar industry". SSRN. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mariolis P, Rock VJ, Asman K; et al. (2006). "Tobacco use among adults—United States, 2005". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 55 (42): 1145–8. PMID 17065979.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "A bill to protect the public health by providing the Food and Drug Administration with certain authority to regulate tobacco products. (Summary)" (Press release). Library of Congress. 2004-05-20. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ^ Template:Cite pmc

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/2261231a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/2261231a0instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10073-4, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0166-2236(96)10073-4instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/382255a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/382255a0instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 761168, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=761168instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8974398, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8974398instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.026, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.01.026instead. - ^ Peto, Richard; Lopez, Alan D; Boreham, Jillian; Thun, Michael (2006). "Mortality from Smoking in Developed Countries 1950-2000: indirect estimates from national vital statistics" (Document). Oxford University Press. p. 9.

{{cite document}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19910909, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19910909instead. - ^ GBD 2008, p. 8

- ^ GBD 2008, p. 23

- ^ a b "WHO/WPRO-Tobacco Fact sheet". World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2007-05-29. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ^ Gay, Peter (1988). Freud: A Life for Our Time. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 650–651. ISBN 0393328619.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/0193-3973(92)90010-F, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/0193-3973(92)90010-Finstead. - ^ Harris, Judith Rich; Pinker, Steven (1998-09-04). "The nurture assumption: why children turn out the way they do" (Document). Simon and Schuster.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.485, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.485instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/713688125, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/713688125instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/0306-4603(90)90067-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/0306-4603(90)90067-8instead. - ^ Michell L, West P (1996). "Peer pressure to smoke: the meaning depends on the method". 11 (1): 39–49.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1300/J079v26n01_03, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1300/J079v26n01_03instead. - ^ Eysenck, Hans J.; Brody, Stuart (2000-11). "Smoking, health and personality" (Document). Transaction.

{{cite document}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00523.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00523.xinstead. - ^ "Nicotine" (Document). Imperial College London.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/tc.12.1.105, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/tc.12.1.105instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.67, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1037/1064-1297.15.1.67instead. - ^ a b Cigarettes Cost U.S. $7 Per Pack Sold, Study Says

- ^ a b Study: Cigarettes cost families, society $41 per pack

- ^ a b "Public Finance Balance of Smoking in the Czech Republic".

- ^ "Snuff the Facts".

- ^ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; Mitchell, Richard (2007-05-18). "Chapter 8: Environmental and Nutritional Diseases". Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. p. 288, Figure 8-6. ISBN 9781416029731.

- ^ WHO global burden of disease report 2008

- ^ WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008

- ^ "Nicotine: A Powerful Addiction." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ Cigarette Smoking Among Adults - United States, 2006

- ^ WHO/WPRO-Smoking Statistics

- ^ Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (2009). "Obey the Word of Wisdom". Basic Beliefs - The Commandments. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ Smith, Peter (2000). "smoking". A concise encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford: Oneworld Publications. p. 323. ISBN 1-85168-184-1.

- ^ Updated status of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- ^ 26, 2004-smoking-costs_x.htm Study: Cigarettes cost families, society $41 per pack

- ^ Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of The Surgeon General

- ^ Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns

- ^ Cigarette Tax Burden - U.S. & International - IPRC

- ^ State Tax Rates on Cigarettes

- ^ Price of cigarettes across the EU

- ^ Smuggling & Crossborder Shopping

- ^ Scollo, Michelle (2008). "13.2 Tobacco taxes in Australia". Tobacco in Australia. Cancer Council Victoria. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ History of Tobacco Regulation

- ^ Television Without Frontiers Directive 1989

- ^ European Union - Tobacco advertising ban takes effect 31 July

- ^ Report on the implementation of the EU Tobacco Advertising Directive

- ^ Tobacco - Health warnings Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved August 29, 2008

- ^ Public Health at a Glance - Tobacco Pack Information

- ^ Tobacco 18

- ^ NFPA:: Press Room:: News releases

- ^ Reynolds Letter

- ^ a b Fire Safe Cigarettes:: Letter to tobacco companies

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00034-4, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00034-4instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2136102, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2136102instead.

Bibliography

- Gilman, Sander L.; Xun, Zhou (2004-08-15). "Smoke: A Global History of Smoking" (Document). Reaktion Books.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - Proctor, Robert N. (2000-11-15). "The Nazi War on Cancer" (Document). Princeton University Press.

{{cite document}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|isbn=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - World Health Organization (2008). The Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update (PDF). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-156371-0. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- World Health Organization (2008). WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package (PDF). World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-159628-2. Retrieved 2008-01-01.