Stephen Hawking

Stephen Hawking | |

|---|---|

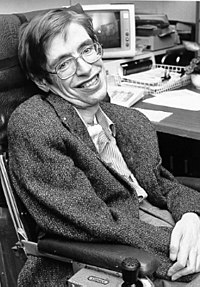

Stephen Hawking at NASA, 1980s | |

| Born | Stephen William Hawking 8 January 1942 Oxford, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouses |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Dennis Sciama |

| Other academic advisors | Robert Berman |

| Notable students | Raymond Laflamme Don Page |

Stephen William Hawking, CH, CBE, FRS, FRSA (born 8 January 1942) is a British theoretical physicist, and author. His key scientific works to date have included providing, with Roger Penrose, theorems regarding the occurrence of gravitational singularities in the framework of general relativity, and the theoretical prediction that black holes should emit radiation, which is today known as Hawking radiation (or sometimes as Bekenstein–Hawking radiation).

He is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and in 2009 was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. Hawking was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge between 1979 and 2009. Subsequently, he became research director at the university's Centre for Theoretical Cosmology.

Hawking has a motor neurone disease related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a condition that has progressed over the years. He is now almost completely paralysed and communicates through a speech generating device. He has been married twice and has three children. Hawking has achieved success with works of popular science in which he discusses his own theories and cosmology in general; these include A Brief History of Time, which stayed on the British Sunday Times best-sellers list for a record-breaking 237 weeks.

Early life and education

Stephen Hawking was born on 8 January 1942 to Frank Hawking, a research biologist, and Isobel Hawking.[1] He has two younger sisters, Philippa and Mary, and an adopted brother, Edward.[2] Although Hawking's parents were living in North London, he was born in Oxford as his parents felt it was safer to stay in Oxford for the later stages of the pregnancy. (London was under attack at the time as part of World War II).[3]

When his father became head of the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research[1] in 1950, Hawking and his family moved to St Albans, Hertfordshire.[3] Hawking attended St Albans High School for Girls from 1950 to 1953 (At that time, boys could attend the girls' school until the age of 10).[2] and then from the age of 11, he attended St Albans School, where he was a good, but not exceptional, student.[3] He maintains his connection with the school, giving his name to one of the four houses and to an extracurricular science lecture series.[4]

Hawking has named his secondary school mathematics teacher Dikran Tahta as an inspiration,[5] and originally wanted to study the subject at university. However, Hawking's father wanted him to apply to University College, Oxford, where his father had attended. As University College did not have a mathematics fellow at that time, applications were not accepted from students who wished to study that discipline. Hawking therefore applied to read natural sciences with an emphasis in Physics. He was accepted and gained a scholarship.[3] While at Oxford, he coxed a rowing team, which, he stated, helped relieve his immense boredom at the university.[6] His physics tutor, Robert Berman, later said "It was only necessary for him to know that something could be done, and he could do it without looking to see how other people did it. ... his mind was completely different from all of his contemporaries".[3]

Hawking's unimpressive study habits resulted in a final examination score on the borderline between first and second class honours, making an "oral examination" necessary.[3] Berman said of the oral examination: "And of course the examiners then were intelligent enough to realize they were talking to someone far more clever than most of themselves".[3] After receiving his B.A. degree at Oxford in 1962, he left for graduate work at Trinity Hall, Cambridge.[3]

Career

1962–1975

Although Hawking started developing symptoms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as soon as he arrived at Cambridge and did not distinguish himself in his first two years at Cambridge, he returned to working on his PhD after the disease had stabilised and with the help of his doctoral tutor, Dennis William Sciama.[7]

When Hawking began his graduate studies in the 1960s, there was much debate in the physics community about the opposing theories of the creation of the universe: big bang, and steady state.[7] Hawking and his Cambridge friend and colleague, Roger Penrose, showed in 1970 that if the universe obeys general relativity and if the universe fits any of the Friedmann models, then the universe must have begun as a singularity.[8] This work showed that, far from being mathematical curiosities which appear only in special cases, singularities are a fairly generic feature of general relativity (see Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems).[9]

Hawking's work with Brandon Carter, Werner Israel and D. Robinson, strongly supported John Wheeler's no-hair theorem – that any black hole is fully described by the three properties of mass, angular momentum, and electric charge.[10] With Bardeen and Carter, he proposed the four laws of black hole mechanics, drawing an analogy with thermodynamics.[11] In 1974, he calculated that black holes should emit thermal radiation, known today as Bekenstein-Hawking radiation, until they exhaust their energy and evaporate.[8]

Hawking was elected one of the youngest Fellows of the Royal Society in 1974,[12] and in the same year he accepted the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Scholar visiting professorship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) to work with his friend, Kip Thorne, who was a faculty member there.[13] He continues to have ties with Caltech, spending a month each year there since 1992.[14]

1975–present

The mid to late 1970s were a period of growing fame and success for Hawking, his work was now much talked about, he was appearing in popular television documentaries and in 1979 he was made the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge, a post he held for 30 years until his retirement in 2009.[14][15] Hawking's inaugural lecture as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics had the title "Is the end in sight for Theoretical Physics" and promoted the idea that supergravity would help resolve many of the outstanding problems physicists were studying. [14]

In collaboration with Jim Hartle, Hawking developed a model in which the universe had no boundary in space-time, replacing the initial singularity of the classical Big Bang models with a region akin to the North Pole: one cannot travel north of the North Pole, but there is no boundary there – it is simply the point where all north-running lines meet and end.[16] While originally the no-boundary proposal predicted a closed universe, discussions with Neil Turok led to the realisation that the no-boundary proposal is also consistent with a universe which is not closed.[17] Later work by Hawking appeared to show that, if this no-boundary proposal is correct, then when the universe stopped expanding and eventually collapsed, time would run backwards (Hawking famously used the example of broken teacups reassembling).[18] However, work by Don Page, a former student of Hawking, led to Hawking withdrawing this concept.[18]

Along with Thomas Hertog at CERN, in 2006 Hawking proposed a theory of "top-down cosmology", which says that the universe had no unique initial state, and therefore it is inappropriate for physicists to attempt to formulate a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one particular initial state.[19] Top-down cosmology posits that in some sense, the present "selects" the past from a superposition of many possible histories. In doing so, the theory suggests a possible resolution of the fine-tuning question.[20]

Thorne–Hawking–Preskill bet

In 1997 Hawking made a public scientific wager with Kip Thorne and John Preskill of Caltech concerning the black hole information paradox.[21] Thorne and Hawking argued that since general relativity made it impossible for black holes to radiate, and lose information, the mass-energy and information carried by Hawking Radiation must be "new", and must not originate from inside the black hole event horizon. Since this contradicted the idea under quantum mechanics of microcausality, quantum mechanics would need to be rewritten. Preskill argued the opposite, that since quantum mechanics suggests that the information emitted by a black hole relates to information that fell in at an earlier time, the view of black holes given by general relativity must be modified in some way.[22] The winner of the bet was to receive an encyclopedia of the loser's choice, from which information may be accessed.[21]

In 2004, Hawking announced that he was conceding the bet, and that he now believed that black hole horizons should fluctuate and leak information, in doing so providing Preskill with a copy of Total Baseball. Comparing the useless information obtainable from a black hole to "burning an encyclopedia", Hawking commented, "I gave John an encyclopedia of baseball, but maybe I should just have given him the ashes".[21]

Recognition

On 19 December 2007, a statue of Hawking by artist Ian Walters was unveiled at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology, University of Cambridge.[23] Buildings named after Hawking include the Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador, El Salvador,[24] the Stephen Hawking Building in Cambridge,[25] and the Stephen Hawking Centre at Perimeter Institute in Canada.[26]

Major awards and honours

- 1975 Eddington Medal[1]

- 1976 Hughes Medal of the Royal Society[1]

- 1979 Albert Einstein Medal[1]

- 1981 Franklin Medal[27]

- 1982 Commander of the Order of the British Empire[1]

- 1985 Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society[1]

- 1986 Member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences[1]

- 1988 Wolf Prize in Physics[1]

- 1989 Companion of Honour[1]

- 1999 Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society[28]

- 2003 Michelson Morley Award of Case Western Reserve University[1]

- 2006 Copley Medal of the Royal Society[29]

- 2008 Fonseca Prize of the University of Santiago de Compostela[30]

- 2009 Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour in the United States[31]

Personal life

Hawking has stated that, having been diagnosed with ALS during an early stage of his graduate work, he did not see much point in obtaining a doctorate if he were to die soon after. Hawking later said that the real turning point was his 1965 marriage to Jane Wilde, a language student.[3] Jane cared for him until 1990 when the couple separated.[1] They had three children: Robert, Lucy, and Timothy.[1] Hawking married his personal care assistant, Elaine Mason, in 1995; [1] the couple divorced In October 2006[32] amid claims by former nurses that she had abused him.[33] In 1999, Jane Hawking published a memoir, Music to Move the Stars, detailing the marriage and its breakdown; in 2010 she published a revised version, Travelling to Infinity, My Life with Stephen.[34]

Illness

Hawking has a motor neurone disease that is related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a condition that has progressed over the years. He is now almost completely paralysed and communicates through a speech generating device. Hawking's illness has progressed more slowly than typical cases of ALS: survival for more than 10 years after diagnosis is uncommon.[35][36]

Symptoms of the disorder first appeared while he was enrolled at University of Cambridge; he lost his balance and fell down a flight of stairs, hitting his head.[6] The diagnosis of motor neurone disease came when Hawking was 21, shortly before his first marriage, and doctors said he would not survive more than two or three years. By 1974, he was unable to feed himself or get out of bed. His speech became slurred so that he could be understood only by people who knew him well. During a visit to CERN in Geneva in 1985, Hawking contracted pneumonia, which in his condition was life-threatening as it further restricted his already limited respiratory capacity. He had an emergency tracheotomy, and as a result lost what remained of his ability to speak.[37] A speech generating device was built in Cambridge, using software from an American company, that enabled Hawking to write onto a computer with small movements of his body, and then have a voice synthesiser speak what he typed.[38]

The particular voice synthesiser hardware he uses, which has an American English accent, is no longer being produced. Asked why he has still kept the same voice after so many years, Hawking stated that he has not heard a voice he likes better and that he identifies with it even though the synthesiser is both large and fragile by current standards. For lectures and media appearances, Hawking appears to speak fluently through his synthesiser; however when preparing answers his system produces words at a rate of about one per minute.[39] Hawking's setup uses a predictive text entry system, which requires only the first few characters in order to auto-complete the word, but as he is only able to use his cheek for data entry, constructing complete sentences takes time.[39]

He describes himself as lucky, despite his disease. Its slow progression has allowed him time to make influential discoveries and has not hindered him from having, in his own words, "a very attractive family".[38]

In popular culture

As a person of great interest to the public, Hawking has been referenced or asked to appear in a great many works of popular culture. Hawking has appeared as himself on episodes of, Star Trek: The Next Generation,[40] The Simpsons, Futurama,[41] and The Big Bang Theory.[42] His actual synthesiser voice was used on parts of the Pink Floyd song "Keep Talking", as well as on Turbonegro's "Intro: The Party Zone".

Hawking's early life and the onset of his illness was the subject of the 2004 BBC4 TV film Hawking in which he was portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch. In 2008, Hawking was the subject of and featured in the documentary series Stephen Hawking, Master of the Universe for Channel 4. In September 2008, Hawking presided over the unveiling of the 'Chronophage' (time-eating) Corpus Clock at Corpus Christi College Cambridge.[43]

Space and spaceflight

Hawking has suggested that space is the Earth's long term hope[44] and has indicated that he is almost certain that alien life exists in other parts of the universe, "To my mathematical brain, the numbers alone make thinking about aliens perfectly rational. The real challenge is to work out what aliens might actually be like".[45] He believes alien life not only certainly exists on planets but perhaps even in other places, like within stars or even floating in outer space. He has also warned that a few of these species might be intelligent and threaten Earth.[46] "If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn't turn out well for the Native Americans," he said.[45] He has advocated that, rather than try to establish contact, humans should try to avoid contact with alien life forms.[45]

In 2007, Hawking took a zero-gravity flight in a "Vomit Comet" of Zero Gravity Corporation, during which he experienced weightlessness eight times.[47] He became the first quadriplegic to float in zero gravity. The fee is normally US$3,750 for 10 to 15 plunges, but Hawking was not required to pay. Before the flight Hawking said:

Many people have asked me why I am taking this flight. I am doing it for many reasons. First of all, I believe that life on Earth is at an ever-increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster such as sudden nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, or other dangers. I think the human race has no future if it doesn't go into space. I therefore want to encourage public interest in space.[48]

Religious and philosophical views

In his early work, Hawking spoke of God in a metaphorical sense, such as in A Brief History of Time: "If we discover a complete theory, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason – for then we should know the mind of God."[49] In the same book he suggested the existence of God was unnecessary to explain the origin of the universe.[50]

His ex-wife, Jane, has described him as an atheist.[51] Hawking has stated that he is "not religious in the normal sense" and he believes that "the universe is governed by the laws of science. The laws may have been decreed by God, but God does not intervene to break the laws."[52] In an interview published in The Guardian newspaper, Hawking regarded the concept of Heaven as a myth, believing that there is "no heaven or afterlife" and that such a notion was a "fairy story for people afraid of the dark."[53][54]

At Google's Zeitgeist Conference in 2011, Hawking said that "philosophy is dead." He believes philosophers "have not kept up with modern developments in science" and that scientists "have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge." He said that philosophical problems can be answered by science, particularly new scientific theories which "lead us to a new and very different picture of the universe and our place in it".[55]

Publications

Hawking's first popular science book, A Brief History of Time, was published on 1 April 1988. It stayed on the British Sunday Times best-sellers list for a record-breaking 237 weeks.[56] A Brief History of Time was followed by The Universe in a Nutshell (2001). A collection of essays titled Black Holes and Baby Universes (1993) was also popular. His book, A Briefer History of Time (2005), co-written by Leonard Mlodinow, updated his earlier works to make them accessible to a wider audience. In 2007 Hawking and his daughter, Lucy Hawking, published George's Secret Key to the Universe, a children's book focusing on science that Lucy Hawking described as "a bit like Harry Potter but without the magic."[57]

Popular

- A Brief History of Time (1988)[58]

- Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (1994) [59]

- The Universe in a Nutshell (2001)[58]

- On The Shoulders of Giants (2002)[58]

- A Briefer History of Time (2005)[58]

- God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History (2005)[58]

- The Grand Design (2010)[58]

Children's fiction

These are co-written with his daughter Lucy.

- George's Secret Key to the Universe, (2007)[58]

- George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt, (2009)[58]

- George and the Big Bang, (2011)[58]

Films and series

- A Brief History of Time (1991)[60]

- Stephen Hawking's Universe (1997)[61]

- Horizon: The Hawking Paradox (2005)[62]

- Masters of Science Fiction (2007)[63]

- Stephen Hawking: Master of the Universe (2008)[64]

- Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking (2010)[65]

- Brave New World with Stephen Hawking (2011)[66]

See also

- Bekenstein–Hawking formula

- Gibbons–Hawking ansatz

- Gibbons–Hawking effect

- Gibbons–Hawking space

- Gibbons–Hawking–York boundary term

- Hartle–Hawking state

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Larsen 2005, pp. x–xix.

- ^ a b Larsen 2005, pp. 3–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ferguson 2011, Chapter 3.

- ^ Kirsop, Sam (13 May 2006). "Hawking Lectures Sign Off with Dinner". St Albans School. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Hoare, Geoffrey; Love, Eric (5 January 2007). "Dick Tahta". guardian.co.uk. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ a b Hawking 1992, p. 44.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, Chapter 4.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, Chapter 6.

- ^ Hawking, Stephen; Penrose, Roger (1970). "The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 314 (1519): 529–548. Bibcode:1970RSPSA.314..529H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1970.0021.

- ^ Hawking & Israel 1989, p. 278.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Ferguson 2011, Chapter 7.

- ^ a b c Ferguson 2011, Chapter 8.

- ^ "Hawking gives up academic title". BBC News. 30 September 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Baird 2007, p. 234.

- ^ Yulsman 2003, pp. 174–176.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2011, Chapter 14.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (26 June 2008). "Stephen Hawking's explosive new theory". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Hawking, S.W.; Hertog, T. (2006). "Populating the landscape: A top-down approach". Physical Review D. 73 (12). arXiv:hep-th/0602091. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.123527.

- ^ a b c Hawking, S.W. (2005). "Information loss in black holes". Physical Review D. 72 (8). arXiv:hep-th/0507171. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.72.084013.

- ^ Preskill, John. "John Preskill's comments about Stephen Hawking's concession". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "Vice-Chancellor unveils Hawking statue". University of Cambridge. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ^ Komar, Oliver; Buechner, Linda (October 2000). "The Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador Central America Honours the Fortitude of a Great Living Scientist". Journal of College Science Teaching. XXX (2). Archived from the original on 30 July 2009. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "The Stephen Hawking Building". BBC News. 18 April 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Grand Opening of the Stephen Hawking Centre at Perimeter Institute". Perimeter Institute. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 63.

- ^ "Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize". American Physical Society. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "Oldest, space-travelled, science prize awarded to Hawking". The Royal Society. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- ^ "Fonseca Prize 2008". University of Santiago de Compostela. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (13 August 2009). "Obama presents presidential medal of freedom to 16 recipients". guardian.co.uk. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Sapsted, David (20 October 2006). "Hawking and second wife agree to divorce". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ "Hawking's nurse reveals why she is not surprised his marriage is over". Daily Mail. 20 October 2006. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Welcome back to the family, Stephen". The Times. 6 May 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ Mitsumoto & Munsat 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Harmon, Katherine (7 January 2012). "How Has Stephen Hawking Lived to 70 with ALS?". Scientific American. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Larsen 2005, p. 72–81.

- ^ a b Hawking, Stephen. "Living with ALS". Stephen Hawking Official Website. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ a b de Lange, Catherine (30 December 2011). "The man who saves Stephen Hawking's voice". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Okuda & Okuda 1999, p. 380.

- ^ Cheng, Maria (5 January 2012). "Stephen Hawking to turn 70, defying disease". Boston.com. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Professor Stephen Hawking films Big Bang Theory cameo". BBC news. 12 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Time to unveil Corpus Clock". Cambridgenetwork.co.uk. 22 September 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (16 October 2001). "Colonies in space may be only hope, says Hawking". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ a b c "Stephen Hawking warns over making contact with aliens". BBC News. 25 April 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Hickman, Leo (25 April 2010). "Stephen Hawking takes a hard line on aliens". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ "Hawking takes zero-gravity flight". BBC News. 27 April 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ "Physicist Hawking experiences zero gravity". CNN. 26 April 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ Sample, Ian (15 May 2011). "Stephen Hawking: 'There is no heaven; it's a fairy story'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (29 December 1991). "Towards a Theory of Everything". The Observer. p. 42.

Though A Brief History of Time brings in God as a useful metaphor, Hawking is an atheist

- ^ Adams, Tim (4 April 2004). "A Brief History of a First Wife". The Observer. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Phil (31 October 2008). "Pope sees physicist Hawking at evolution gathering". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Sample, Ian (15 May 2011). "Stephen Hawking: 'There is no heaven; it's a fairy story'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking: Heaven Is A Myth". The Huffington Post. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Warman, Matt (17 May 2011). "Stephen Hawking tells Google 'philosophy is dead'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ Radford, Tim (31 July 2009). "How God propelled Stephen Hawking into the bestsellers lists". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Man must conquer other planets to survive, says Hawking". Daily Mail. 13 June 2006. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Books". Stephen Hawking Official Website. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Black Holes and Baby Universes". Kirkus Reviews. 20 March 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "A Brief History of Time: Synopsis". Errol Morris. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking's Universe". PBS. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "The Hawking Paradox". BBC. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Stephen Hawking's Sci Fi Masters". Science Channel. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Master of the Universe". Channel 4. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ "Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking". Discovery Channel. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Brave New World with Stephen Hawking". Channel 4. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

Bibliography

- Baird, Eric (2007). Relativity in Curved Spacetime: Life Without Special Relativity. Chocolate Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-9557068-0-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Ferguson, Kitty (2011). Stephen Hawking: His Life and Work. Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4481-1047-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hawking, Stephen W.; Israel, Werner (1989). Three Hundred Years of Gravitation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37976-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hawking, Stephen W. (1992). Stephen Hawking's A brief history of time: a reader's companion. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-07772-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hawking, Stephen W. (1994). Black holes and baby universes and other essays. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-37411-7.

- Larsen, Kristine (2005). Stephen Hawking: a biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32392-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Okuda, Michael; Okuda, Denise (1999). The Star trek encyclopedia: a reference guide to the future. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-671-53609-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Mitsumoto, Hiroshi; Munsat, Theodore L. (2001). Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a guide for patients and families. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-888799-28-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Yulsman, Tom (2003). Origins: the quest for our cosmic roots. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-7503-0765-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Boslough, John (1 June 1989). Stephen Hawking's universe: an introduction to the most remarkable scientist of our time. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-70763-8. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- Pickover, Clifford A. (16 April 2008). Archimedes to Hawking: laws of science and the great minds behind them. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533611-5. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

External links

- Stephen Hawking's web site

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Stephen Hawking at IMDb

- Stephen Hawking at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Template:Worldcat id

- Stephen Hawking collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Stephen Hawking collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- "Archival material relating to Stephen Hawking". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Stephen William Hawking at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Use dmy dates from March 2012

- 1942 births

- Academics of the University of Cambridge

- Adams Prize recipients

- Albert Einstein Medal recipients

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- Alumni of University College, Oxford

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Cosmologists

- English astronomers

- English atheists

- English people with disabilities

- English physicists

- English science writers

- Fellows of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- People educated at St Albans School, Hertfordshire

- Honorary Fellows of University College, Oxford

- Living people

- Lucasian Professors of Mathematics

- Members of the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Mental calculators

- People educated at St Albans High School for Girls

- People from Oxford

- People from St Albans

- People with motor neurone disease

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Recipients of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Religious skeptics

- Theoretical physicists

- Wolf Prize in Physics laureates

- 20th-century philosophers

- 21st-century philosophers