Down syndrome

| Down syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics, neurology |

| Frequency | 0.1% |

Down syndrome (DS) or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21.[1] Down syndrome is the most common chromosome abnormality in humans.[2] The CDC estimates that about one of every 691 babies born in the United States each year is born with Down syndrome.[3] It is typically associated with physical growth delays, a particular set of facial characteristics and a severe degree of intellectual disability.[1] The average full-scale IQ of young adults with Down syndrome is around 50 (70 and below is defined as the cut-off for intellectual disability), whereas young adult controls have an average IQ of 100.[1][4]

Many children with Down syndrome are educated in regular school classes while others require specialised educational facilities. Some children graduate from high school,[5] and, in the US, there are increasing opportunities for participating in post-secondary education.[6] Education and proper care has been shown to improve quality of life significantly.[7] Many adults with Down syndrome are able to work at paid employment in the community, while others require a more sheltered work environment.[5]

Down syndrome is named after John Langdon Down, the British physician who described the syndrome in 1866.[8] The condition was clinically described earlier by Jean Etienne Dominique Esquirol in 1838 and Edouard Seguin in 1844.[9] Down syndrome was identified as a chromosome 21 trisomy by Dr. Jérôme Lejeune in 1959. Down syndrome can be identified in a newborn by direct observation or in a fetus by prenatal screening.[1][10] Pregnancies with this diagnosis are often terminated.[11]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of Down syndrome are characterized by the neotenization of the brain and body.[12] Down syndrome is characterized by decelerated maturation (neoteny), incomplete morphogenesis (vestigia) and atavisms.[13] Individuals with Down syndrome may have some or all of the following physical characteristics: microgenia (abnormally small chin),[14] oblique eye fissures on the inner corner of the eyes,[15][16] muscle hypotonia (poor muscle tone), a flat nasal bridge, a single palmar fold, a protruding tongue (due to small oral cavity, and an enlarged tongue near the tonsils) or macroglossia,[15][16] "face is flat and broad",[17] a short neck, white spots on the iris known as Brushfield spots,[18] excessive joint laxity including atlanto-axial instability, excessive space between large toe and second toe, a single flexion furrow of the fifth finger, a higher number of ulnar loop dermatoglyphs and short fingers.[16]

Growth parameters such as height, weight, and head circumference are smaller in children with DS than with typical individuals of the same age. Adults with DS tend to have short stature and bowed legs[16]—the average height for men is 5 feet 1 inch (154 cm) and for women is 4 feet 9 inches (144 cm).[19] Individuals with DS are also at increased risk for obesity as they age.[20]

| Characteristics | Percentage[21] | Characteristics | Percentage[21] |

|---|---|---|---|

| stunted growth | 100% | flattened nose | 60% |

| mental retardation | 99.8% | small teeth | 60% |

| atypical fingerprints | 90% | clinodactyly | 52% |

| separation of the abdominal muscles | 80% | umbilical hernia | 51% |

| flexible ligaments | 80% | short neck | 50% |

| hypotonia | 80% | shortened hands | 50% |

| brachycephaly | 75% | congenital heart disease | 45% |

| smaller genitalia | 75% | single transverse palmar crease | 45% |

| eyelid crease | 75% | macroglossia (larger tongue) | 43% |

| shortened extremities | 70% | epicanthic fold | 42% |

| oval palate | 69% | strabismus | 40% |

| low-set and rounded ear | 60% | Brushfield spots (iris) | 35% |

Individuals with Down syndrome have a higher risk for many conditions. The medical consequences of the extra genetic material in Down syndrome are highly variable, may affect the function of any organ system or bodily process, and can contribute to a shorter life expectancy for people with Down syndrome. Following improvements to medical care, particularly with heart problems, the life expectancy among persons with Down syndrome has increased from 12 years in 1912, to 60 years.[22]

In March 2012, the Guinness Book of Records website listed Joyce Greenman, now 87, of London, who was born on March 14, 1925, as the oldest living person with Down syndrome, (recorded correct and checked as of 29 April 2008). The causes of death have also changed, with chronic neurodegenerative diseases becoming more common as the population ages. Most people with Down syndrome who live into their 40s and 50s begin to suffer from dementia like Alzheimer's disease.[23]

The American Academy of Pediatrics, among other health organizations, has issued a series of recommendations for screening individuals with Down syndrome for particular diseases.[24]

Neurological effects

Most individuals with Down syndrome have intellectual disability in the mild (IQ 50–70) to moderate (IQ 35–50) range,[25] with individuals having Mosaic Down syndrome typically 10–30 points higher.[26] The methodology of the IQ tests has been criticised for not taking into account accompanying physical disabilities, such as hearing and vision impairment, that would slow performance.[27]

Language skills show a difference between understanding speech and expressing speech, and commonly individuals with Down syndrome have a speech delay.[28] Fine motor skills are delayed[29] and often lag behind gross motor skills and can interfere with cognitive development. Effects of the condition on the development of gross motor skills are quite variable. Some children will begin walking at around 2 years of age, while others will not walk until age four. Physical therapy, and/or participation in a program of adapted physical education (APE), may promote enhanced development of gross motor skills in Down syndrome children.[30]

Children and adults with DS are at increased risk for developing epilepsy and also Alzheimer's disease.[31]

Congenital heart disease

The incidence of congenital heart disease in newborn babies with Down syndrome is up to 50%.[32] An atrioventricular septal defect also known as endocardial cushion defect is the most common form with up to 40% of patients affected. This is closely followed by ventricular septal defect that affects approximately 35% of patients.[32]

Cancer

Although the general incidence of cancer amongst individuals with Down syndrome is the same as in the general population,[33] there are greatly reduced incidences of many common malignancies except leukemia and testicular cancer.[34] People with Down syndrome also have a much lower risk of hardening of the arteries and diabetic retinopathy.[35]

Hematologic malignancies such as leukemia are more common in children with DS.[36] In particular, acute lymphoblastic leukemia is at least 10 times more common in DS and the megakaryoblastic form of acute myelogenous leukemia is at least 50 times more common in DS. Transient leukemia is a form of leukemia that is rare in individuals without DS but affects up to 20 percent of newborns with DS.[37] This form of leukemia is typically benign and resolves on its own over several months, though it can lead to other serious illnesses.[38] In contrast to hematologic malignancies, solid tumor malignancies are less common in DS, possibly due to increased numbers of tumor suppressor genes contained in the extra genetic material.[39]

Thyroid disorders

Individuals with DS are at increased risk for dysfunction of the thyroid gland, an organ that helps control metabolism. Low thyroid (hypothyroidism) is most common, occurring in almost a third of those with DS. This can be due to absence of the thyroid at birth (congenital hypothyroidism) or due to attack on the thyroid by the immune system.[40]

Gastrointestinal

Down syndrome increases the risk of Hirschsprung's disease, in which the nerve cells that control the function of parts of the colon are not present.[41] This results in severe constipation. Other congenital anomalies occurring more frequently in DS include duodenal atresia, annular pancreas, and imperforate anus. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and celiac disease are also more common among people with DS.[42]

Infertility

Males with Down syndrome usually cannot father children, while females demonstrate significantly lower rates of conception relative to unaffected individuals.[43] Women with DS are less fertile and often have difficulties with miscarriage, premature birth, and difficult labor. Without preimplantation genetic diagnosis, approximately half of the offspring of someone with Down syndrome also have the syndrome themselves.[43] Men with DS are almost uniformly infertile, exhibiting defects in spermatogenesis.[44] There have been only three recorded instances of males with Down syndrome fathering children.[45][46]

Eye disorders

Eye disorders are more common in people with DS. Almost half have strabismus, in which the two eyes do not move in tandem. Refractive errors requiring glasses or contacts are also common. Cataracts (opacity of the lens), keratoconus (thin, cone-shaped corneas), and glaucoma (increased eye pressures) are also more common in DS.[47] Brushfield spots (small white or grayish/brown spots on the periphery of the iris) may be present.

Hearing disorders

In general, hearing impairment and otological problems are found in 38-78% of children with Down syndrome compared to 2.5% of normal children.[48][49][50] However, attentive diagnosis and aggressive treatment of chronic ear disease (e.g. otitis media, also known as glue-ear) in children with Down syndrome can bring approximately 98% of the children up to normal hearing levels.[51]

The elevated occurrence of hearing loss in individuals with Down syndrome is not surprising. Every component in the auditory system is potentially adversely affected by Down syndrome.[50]

Otitis media with effusion is the most common cause of hearing loss in Down children;[49] the infections start at birth and continue throughout the children's lives.[52] The ear infections are mainly associated with Eustachian tube dysfunction due to alterations in the skull base. However, excessive accumulation of wax can also cause obstruction of the outer ear canal as it is often narrowed in children with Down syndrome.[53] Middle ear problems account for 83% of hearing loss in children with Down syndrome.[53] The degree of hearing loss varies but even a mild degree can have major consequences for speech perception, language acquisition, development and academic achievement[52] if not detected in time and corrected.[49]

Early intervention to treat the hearing loss and adapted education are useful to facilitate the development of children with Down syndrome, especially during the preschool period. For adults, social independence depends largely on the ability to complete tasks without assistance, the willingness to separate emotionally from parents and access to personal recreational activities.[48] Given this background it is always important to rule out hearing loss as a contributing factor in social and mental deterioration.[50]

Other complications

Instability of the atlanto-axial joint occurs in approximately 15% of people with DS, probably due to ligamental laxity. It may lead to the neurologic symptoms of spinal cord compression.[54]

Genetics

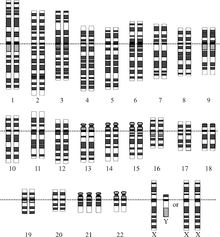

Down syndrome disorders are based on having too many copies of the genes located on chromosome 21. In general, this leads to an overexpression of the genes.[55] Understanding the genes involved may help to target medical treatment to individuals with Down syndrome. It is estimated that chromosome 21 contains 200 to 250 genes.[56] Recent research has identified a region of the chromosome that contains the main genes responsible for the pathogenesis of Down syndrome.[57]

The extra chromosomal material can come about in several distinct ways. A typical human karyotype is designated as 46,XX or 46,XY, indicating 46 chromosomes with an XX arrangement typical of females and 46 chromosomes with an XY arrangement typical of males.[58] In 1–2% of the observed Down syndromes.[59] Some of the cells in the body are normal and other cells have trisomy 21, this is called mosaic Down syndrome (46,XX/47,XX,+21).[60][61]

Trisomy 21

Trisomy 21 (47,XX,+21) is caused by a meiotic nondisjunction event. With nondisjunction, a gamete (i.e., a sperm or egg cell) is produced with an extra copy of chromosome 21; the gamete thus has 24 chromosomes. When combined with a normal gamete from the other parent, the embryo now has 47 chromosomes, with three copies of chromosome 21. Trisomy 21 is the cause of approximately 95% of observed Down syndromes, with 88% coming from nondisjunction in the maternal gamete and 8% coming from nondisjunction in the paternal gamete.[59] The actual Down syndrome "critical region" encompasses chromosome bands 21q22.1-q22.3.[62]

Robertsonian translocation

The extra chromosome 21 material that causes Down syndrome may be due to a Robertsonian translocation in the karyotype of one of the parents. In this case, the long arm of chromosome 21 is attached to another chromosome, often chromosome 14 [45,XX,der(14;21)(q10;q10)]. A person with such a translocation is phenotypically normal. During reproduction, normal disjunctions leading to gametes have a significant chance of creating a gamete with an extra chromosome 21, producing a child with Down syndrome. Translocation Down syndrome is often referred to as familial Down syndrome. It is the cause of 2–3% of observed cases of Down syndrome.[59] It does not show the maternal age effect, and is just as likely to have come from fathers as mothers.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Prenatal testing

Both ACOG and NICE guidelines recommend that screening for Down syndrome be offered to all pregnant women, regardless of age.[63][64]

A number of tests can be used to screen for Down syndrome, with varying levels of accuracy and invasiveness. They are usually used in combination to increase their detection rate, while maintaining a low false positive rate.

| Screen | When performed (weeks gestation) | Detection rate | False positive rate | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined test (Nuchal translucency/free beta-hCG/PAPP-A screen) | 10–13.5 | 85%[65] | 5% | Uses ultrasound to measure Nuchal Translucency in addition to the free beta-hCG and PAPP-A (pregnancy-associated plasma protein A). NIH has confirmed that this first trimester test is more accurate than second trimester screening methods.[66] |

| Quad screen | 15–20 | 81%[35] | 5% | This test measures the maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein, unconjugated estriol, beta-hCG, and inhibin-Alpha (INHA).[67] |

| Integrated test | 15-20 | 95%[68] | 5% | The integrated test uses measurements from both the 1st trimester combined test and the 2nd trimester quad test to yield a more accurate screening result. Because all of these tests are dependent on accurate calculation of the gestational age of the fetus, the real-world false-positive rate is >5% and may be closer to 7.5%.[citation needed] |

Ultrasound

Ultrasound imaging can be used to screen for Down syndrome. Increased fetal nuchal translucency (NT) is an indicator of increased risk of Down syndrome. A 2003 systematic review of 30 studies of NT in Down syndrome found an average sensitivity of 75-80% with a false positive rate of 5.8-6% (95% confidence intervals).[69] Therefore, while the false positive rate is too high for NT to be used alone as a screening test, it is useful as part of a combined test. Ultrasound measurement of NT is usually performed between 11 and 14 weeks gestation.

Other ultrasound findings have been associated with Down syndrome. Absence of the fetal nasal bone has been associated with Down syndrome. A 2001 observational study suggested that there is an increased rate of absence of nasal bone in fetuses with Down syndrome.[70] However, it is unclear how useful this would be as a screening test as the reproducibility and consistency of the procedure has not been demonstrated.

Blood tests

Several blood markers can be measured that can be used as part of combined tests to predict the risk of Down syndrome. These include α-fetoprotein, β-hCG, inhibin-A, PAPP-A and unconjugated estriol.

During the first trimester, a combination of β-hCG and PAPP-A levels can give a 60% detection rate at a 5% false positive rate.[71]

In the second trimester, various markers including β-hCG, inhibin-A, α-fetoprotein and unconjugated estriol can be used to give detection rates between 60 and 70%.[72]

Several non-invasive prenatal tests which employ DNA sequencing of fragments of fetal DNA in the mother's blood have been developed. The main method is to obtain maternal blood through venipuncture for analysis of cell-free fetal DNA (cffDNA). It can be performed at 10 weeks of gestational age.[73] Methods to analyze cffDNA are mainly either massively parallel sequencing (MPSS) or directed DNA analysis, wherein the former analyzes a random subset of cffDNA fragments.[73] MPSS is estimated to have a sensitivity of between 96 and 100%, and a specificity between 94 and 100% for detecting Down syndrome.[74] The International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis finds that this is an advanced screening test which may be of use, in conjunction with genetic counseling, in high-risk cases based upon existing screening strategies. While effective in the diagnosis of Down syndrome, it cannot assess other conditions which can be detected by invasive testing; (for pregnant women who are screen-positive using current screening protocols, Down syndrome represents about half of the fetal chromosomal abnormalities identified through amniocentesis and CVS).[75]

Amniocentesis and CVS

Where screening tests predict a high risk of the fetus having Down syndrome, more invasive diagnostic tests such as amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling may be performed. These tests have a much lower false positive rate than the screening tests, therefore they are more reliable in establishing the diagnosis of Down syndrome. However, they are invasive, and carry a slightly increased risk of miscarriage.

Abortion rates

A 2002 literature review of elective abortion rates found that 91–93% of pregnancies in the United Kingdom and Europe with a diagnosis of Down syndrome were terminated.[11] Data from the National Down Syndrome Cytogenetic Register in the United Kingdom indicates that from 1989 to 2006 the proportion of women choosing to terminate a pregnancy following prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome has remained constant at around 92%.[76][77]

In the United States a number of studies have examined the abortion rate of fetuses with Down syndrome. Three studies estimated the termination rates at 95%, 98%, and 87%.[11]

Postnatal diagnosis

In cases where prenatal tests have been negative or have not been performed, midwifery staff usually express the initial concern that a newborn has Down syndrome, such as by distinctive signs or by general appearance.[78] Clinical examination by a pediatrician can often confirm or refute this suspicion with confidence.[78] Systems of diagnostic criteria for such an examination include Fried's diagnostic index, which includes the following 8 signs: flat face, ear dysplasia, tongue protrusion, corners of mouth turned down, hypotonia, neck skin excess, epicanthic fold, and a gap between 1st and 2nd toes.[78] With 0 to 2 of these characteristics the newborn can likely be said to not have Down syndrome (with less than one in 100 false negatives), with 3 to 5 of these characteristics the situation is unclear (and genetic testing is recommended) and with 6 to 8 characteristics the newborn can confidently be said to have Down syndrome (with less than one in 100.000 false positives).[78] In cases where there are no clinical grounds for making the diagnosis, it has been suggested that parents can reasonably be kept unaware of the initial suspicion.[78] When the diagnosis remains possible, it is recommended to perform karyotype testing and inform the parents.[78]

Management

| Test | Age |

|---|---|

| Hearing test | 6 months, 12 months, then 1/year |

| T4 and TSH | 6 months, then 1/year |

| Ophthalmic evaluation | 6 months, then 1/year |

| Dental examination | 2 years, then every 6 months. |

| Coeliac disease screening | Between 2 and 3 years of age, or earlier if symptoms occur. |

| Baseline polysomnography | 3 to 4 years, or earlier if symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea occur. |

| Cervical neck x-rays | Between 3 and 5 years of age |

Many children with Down syndrome graduate from high school and can do paid work,[5] or participate in university education.[6] Management strategies such as Early childhood intervention, screening for common problems, medical treatment where indicated, a conducive family environment, and vocational training can improve the overall development of children with Down syndrome. Education and proper care will improve quality of life significantly.[7]

Plastic surgery

Plastic surgery has sometimes been advocated and performed on children with Down syndrome, based on the assumption that surgery can reduce the facial features associated with Down syndrome, therefore decreasing social stigma, and leading to a better quality of life.[80] Plastic surgery on children with Down syndrome is uncommon,[81] and continues to be controversial. Researchers have found that for facial reconstruction, "... although most patients reported improvements in their child's speech and appearance, independent raters could not readily discern improvement ..."[82] For partial glossectomy (tongue reduction), one researcher found that 1 out of 3 patients "achieved oral competence," with 2 out of 3 showing speech improvement.[83] Len Leshin, physician and author of the ds-health website, has stated, "Despite being in use for over twenty years, there is still not a lot of solid evidence in favor of the use of plastic surgery in children with Down syndrome."[84] The U.S. National Down Syndrome Society has issued a "Position Statement on Cosmetic Surgery for Children with Down Syndrome",[85] which states "The goal of inclusion and acceptance is mutual respect based on who we are as individuals, not how we look."

Cognitive development

Individuals with Down syndrome differ considerably in their language and communication skills. It is routine to screen for middle ear problems and hearing loss; low gain hearing aids or other amplification devices can be useful for language learning. Early communication intervention fosters linguistic skills. Language assessments can help profile strengths and weaknesses; for example, it is common for receptive language skills to exceed expressive skills. Individualized speech therapy can target specific speech errors, increase speech intelligibility, and in some cases encourage advanced language and literacy. Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) methods, such as pointing, body language, objects, or graphics are often used to aid communication. Relatively little research has focused on the effectiveness of communications intervention strategies.[86]

Children with Down syndrome may not age emotionally/socially and intellectually at the same rates as children without Down syndrome, so over time the intellectual and emotional gap between children with and without Down syndrome may widen. Complex thinking as required in sciences but also in history, the arts, and other subjects can often be beyond the abilities of some, or achieved much later than in other children. Children with Down syndrome may benefit from mainstreaming (whereby students of differing abilities are placed in classes with their chronological peers) provided that some adjustments are made to the curriculum.[87]

Speech delay may require speech therapy to improve expressive language.[28]

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, Down syndrome results in about 17,000 deaths.[88] About 1 out of every 691 babies born in the United States each year is born with Down syndrome.[3] Each year about 6,000 babies in the United States are born with this condition. Approximately 95% of these are trisomy 21.

Maternal age influences the chances of conceiving a baby with Down syndrome. At maternal age 20 to 24, the probability is one in 1562; at age 35 to 39 the probability is one in 214, and above age 45 the probability is one in 19.[89] Although the probability increases with maternal age, 80% of children with Down syndrome are born to women under the age of 35,[90] reflecting the overall fertility of that age group. Recent data also suggest that paternal age, especially beyond 42,[91] also increases the risk of Down syndrome manifesting.[92]

History

English physician John Langdon Down first characterized Down syndrome as a distinct form of mental disability in 1862, and in a more widely published report in 1866.[93] Due to his perception that children with Down syndrome shared physical facial similarities (epicanthic folds) with those of Blumenbach's Mongolian race, Down used the term mongoloid, derived from prevailing ethnic theory.[17] While the term "mongoloid" (also "mongol" or "mongoloid idiot") continued to be used until the early 1970s, it is now considered pejorative and inaccurate and is no longer in common use.[94]

By the 20th century, Down syndrome had become the most recognizable form of mental disability. Most individuals with Down syndrome were institutionalized, few of the associated medical problems were treated, and most died in infancy or early adult life. With the rise of the eugenics movement, 33 of the (then) 48 U.S. states and several countries began programs of forced sterilization of individuals with Down syndrome and comparable degrees of disability. "Action T4" in Nazi Germany made public policy of a program of systematic involuntary euthanization.[95]

Until the middle of the 20th century, the cause of Down syndrome remained unknown. However, the presence in all races, the association with older maternal age, and the rarity of recurrence had been noticed. Standard medical texts assumed it was caused by a combination of inheritable factors that had not been identified. Other theories focused on injuries sustained during birth.[96]

With the discovery of karyotype techniques in the 1950s, it became possible to identify abnormalities of chromosomal number or shape. In 1958, Jérôme Lejeune discovered that Down syndrome resulted from an extra chromosome.[97] and, as a result, the condition became known as trisomy 21.[95]

In 1961, 18 geneticists wrote to the editor of The Lancet suggesting that Mongolian idiocy had "misleading connotations," had become "an embarrassing term," and should be changed.[98] The Lancet supported Down's Syndrome. The World Health Organization (WHO) officially dropped references to mongolism in 1965 after a request by the Mongolian delegate.[94] Advocacy groups adapted and parents groups welcomed the elimination of the Mongoloid label that had been a burden to their children. The first parents group in the United States, the Mongoloid Development Council, changed its name to the National Association for Down Syndrome in 1972.[99]

In 1975, the United States National Institutes of Health convened a conference to standardize the nomenclature of malformations. They recommended eliminating the possessive form: "The possessive use of an eponym should be discontinued, since the author neither had nor owned the condition."[100] Although both the possessive and non-possessive forms are used in the general population, Down syndrome is the accepted term among professionals in the U.S., Canada and other countries; Down's syndrome is still used in the UK and other areas.[101]

Society and culture

In most developed countries, since the early 20th century many people with Down syndrome were housed in institutions or colonies and excluded from society. However, since the early 1960s parents and their organizations, educators and other professionals have generally advocated a policy of inclusion,[102] bringing people with mental and/or physical disabilities into general society as much as possible. Organizations advocating for the inclusion of people with Down Syndrome include MENCAP advocating for all people with mental disabilities, which was founded in the UK in 1946 by Judy Fryd;[103] the National Association for Down Syndrome, the first known organization advocating for Down syndrome individuals in the United States, which was founded by Kathryn McGee in 1960;[104] the National Down Syndrome Congress, the first truly national organization in the U.S. advocating for Down syndrome families, founded in 1973 by Kathryn McGee and others,[105] and the National Down Syndrome Society, founded in 1979 in the U.S.[106]

In May 2008, the [U.S.] Congressional Down Syndrome Caucus (CDSC) was formed under the leadership of congresswoman Cathy McMorris Rodgers, to educate members of congress and their staff about Down syndrome and work with the National Down Syndrome Society to support legislative activities to improve Down syndrome research, education, and treatment, and promote public policies that would enhance the quality of life for those with Down syndrome.[107]

In September 2011, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established an NIH Down Syndrome Consortium. The purpose of the Consortium is to foster the exchange of information on biomedical and biobehavioral research on Down syndrome being conducted by NIH institutes and centers working on Down syndrome-related topics and the national Down syndrome community.[107]

Ethical issues

Medical ethicist Ronald Green argues that parents have an obligation to avoid 'genetic harm' to their offspring,[108] and Claire Rayner, then a patron of the Down's Syndrome Association, defended testing and abortion saying

"The hard facts are that it is costly in terms of human effort, compassion, energy, and finite resources such as money, to care for individuals with handicaps ... People who are not yet parents should ask themselves if they have the right to inflict such burdens on others, however willing they are themselves to take their share of the burden in the beginning."[109]

Some physicians and ethicists are concerned about the ethical ramifications of the high abortion rate for this condition.[110] Conservative commentator and father of a son with Down syndrome George Will called it "eugenics by abortion".[111][112] British peer Lord Rix stated that "alas, the birth of a child with Down's syndrome is still considered by many to be an utter tragedy" and that the "ghost of the biologist Sir Francis Galton, who founded the eugenics movement in 1885, still stalks the corridors of many a teaching hospital".[113] Doctor David Mortimer has argued in Ethics & Medicine that "Down's syndrome infants have long been disparaged by some doctors and government bean counters."[114] Some members of the disability rights movement "believe that public support for prenatal diagnosis and abortion based on disability contravenes the movement's basic philosophy and goals."[115] Peter Singer argued that

"neither haemophilia nor Down's syndrome is so crippling as to make life not worth living from the inner perspective of the person with the condition. To abort a fetus with one of these disabilities, intending to have another child who will not be disabled, is to treat fetuses as interchangeable or replaceable. If the mother has previously decided to have a certain number of children, say two, then what she is doing, in effect, is rejecting one potential child in favour of another. She could, in defence of her actions, say: the loss of life of the aborted fetus is outweighed by the gain of a better life for the normal child who will be conceived only if the disabled one dies."[116]

World Down Syndrome Day

The first World Down Syndrome Day (WDSD) was held on 21 March 2006. The day and month were chosen to correspond with 21 and trisomy respectively. It was proclaimed by European Down Syndrome Association during their European congress in Palma de Mallorca (February 2005). In the United States, the National Down Syndrome Society observes Down Syndrome Month every October as "a forum for dispelling stereotypes, providing accurate information, and raising awareness of the potential of individuals with Down syndrome."[117] In South Africa, Down Syndrome Awareness Day is held every October 20.[118]

Notable individuals

- Chris Burke is an American actor, folk singer, and motivational speaker. He is best known for his character Charles "Corky" Thacher on the television series Life Goes On.[citation needed]

- Andrea Friedman: actress who portrayed Corky's girlfriend Amanda in Life Goes On and Ellen in the Family Guy episode "Extra Large Medium".[119]

- Dr. Karen Gaffney became the first living person with Down syndrome to receive a Doctor of Humane Letters degree, presented by the University of Portland in 2013, for her long-standing humanitarian work in raising awareness about the capabilities of people who have Down syndrome through her roles as an accomplished sports figure, public speaker, and advocate.[120]

- Stephane Ginnsz, actor — In 1996 was the first actor with Down syndrome in the lead part of a motion picture, Duo.[121]

- Sandra Jensen was denied a heart-lung transplant by the Stanford University School of Medicine in California because she had Down syndrome. After pressure from disability rights activists, Stanford University School of Medicine administrators reversed their decision. In 1996, Jensen became the first person with Down syndrome to receive a heart-lung transplant.[122]

- Tommy Jessop, British actor who starred with Nicholas Hoult in the BAFTA-nominated BBC drama Coming Down the Mountain.[123] In 2012 he became the first actor with Down Syndrome to play Hamlet professionally, in a production by Blue Apple Theatre.[124]

- Rene Moreno, subject of "Up Syndrome"—a documentary film about life with Down syndrome.[125][126]

- Joey Moss, Edmonton Oilers locker room attendant.[127]

- Pablo Pineda, Spanish actor who starred in the semi-autobiographical film Yo También and first student with Down syndrome in Europe to obtain a university degree.[128]

- Lauren Potter, American actress, best known for her role as Becky Jackson on the television show Glee.

- Isabella Pujols, adopted daughter of Los Angeles Angels first baseman Albert Pujols and inspiration for the Pujols Family Foundation.[129]

- Paula Sage, Scottish film actress and Special Olympics netball athlete.[130] Her role in the 2003 film AfterLife brought her a BAFTA Scotland award for best first time performance and Best Actress in the Bratislava International Film Festival, 2004.[131]

- Judith Scott (May 1, 1943 – March 15, 2005) was a highly regarded American outsider sculptor and fiber artist, whose work features in a number of galleries.[132]

- Giusi Spagnolo was the first woman with Down Syndrome to graduate from university in Europe (she graduated from the University of Palermo in Italy in 2011).[133][134]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Gordon Grant; Peter Goward; Paul Ramcharan (1 May 2010). Learning Disability: A Life Cycle Approach to Valuing People. McGraw-Hill International. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-335-21439-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Amniocentesis - American Pregnancy Association". Americanpregnancy.org. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ a b "CDC - Birth Defects, Down Syndrome - NCBDDD". Cdc.gov. 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ Liptak, Gregory S (December 2008). "Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21; Trisomy G)". Merck Manual. Retrieved 2010-12-04.

Symptoms

- ^ a b c "Facts About Down Syndrome". National Association for Down Syndrome. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b Calefati, Jessica (13 February 2009). "College Is Possible for Students With Intellectual Disabilities". US News and World Report. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ a b Roizen, NJ; Patterson, D (2003). "Down's syndrome". Lancet. 361 (9365): 1281–89. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. PMID 12699967.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Janet Carr; Janet H. Carr (24 November 1995). Down's Syndrome: Children Growing Up. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-46933-3. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Genes, Nicholas. "Down Syndrome Through the Ages". the good old days... med Gadget. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Lennard J. Davis (26 February 2010). The Disability Studies Reader. Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-415-87374-1. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Caroline Mansfield, Suellen Hopfer, Theresa M Marteau (1999). "Termination rates after prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome, spina bifida, anencephaly, and Turner and Klinefelter syndromes: a systematic literature review". Prenatal Diagnosis. 19 (9): 808–12. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199909)19:9<808::AID-PD637>3.0.CO;2-B. PMID 10521836.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) This is similar to 90% results found by Britt, David W; Risinger, Samantha T; Miller, Virginia; Mans, Mary K; Krivchenia, Eric L; Evans, Mark I (1999). "Determinants of parental decisions after the prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: Bringing in context". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 93 (5): 410–16. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(20000828)93:5<410::AID-AJMG12>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10951466.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Opitz John M., Gilbert-Barness Enid F. (1990). "Reflections on the Pathogenesis of Down Syndrome". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 7: 38–51 [44]. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320370707. PMID 2149972.

- ^ Optiz, J.M. (1990). Reflections on the pathogenesis of Down syndrome. In American Journal of Medical Genetics Supplement. 7:38.

- ^ Meira Weiss (1994-02). Conditional love: parents' attitudes toward handicapped children. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-89789-324-4. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b This discussion by Myron Belfer, MD, book by Gottfried Lemperie, MD, and Dorin Radu, MD (1980). "Facial Plastic Surgery in Children with Down's Syndrome (preview page, with link to full content on plasreconsurg.com)". p. 343. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Richards, M.C. Toward wholeness: Rudolf Steiner education in America. 1980. University Press of New England, N.H.

- ^ a b Conor, WO (1999). "John Langdon Down: The Man and the Message". Down Syndrome Research and Practice. 6 (1): 19–24. doi:10.3104/perspectives.94.

- ^ "Definition of Brushfield's Spots".

- ^ Cronk, C; Crocker, AC; Pueschel, SM; Shea, AM; Zackai, E; Pickens, G; Reed, RB (1988). "Growth charts for children with Down syndrome: 1 month to 18 years of age". Pediatrics. 81 (1): 102–10. PMID 2962062.

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ a b Fuente: Series de porcentajes obtenidas en un amplio estudio realizado por el CMD (Centro Médico Down) de la Fundación Catalana del Síndrome de Down, sobre 796 personas con SD. Estudio completo en Josep M. Corretger et al (2005). Síndrome de Down: Aspectos médicos actuales. Ed. Masson, para la Fundación Catalana del Síndrome de Down. ISBN 84-458-1504-0. Pag. 24-32.

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ McPhee, J; Tierney, Lawrence M; Papadakis, Maxine A (1999). Current medical diagnosis & treatment 1999. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange. p. 1546. ISBN 0-8385-1550-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics (2001). "Health Supervision for Children With Down Syndrome". Pediatrics. 107 (2): 442–49. Retrieved 13 August 2006.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Genetics (2001). "American Academy of Pediatrics: Health supervision for children with Down syndrome". Pediatrics. 107 (2): 442–49. doi:10.1542/peds.107.2.442. PMID 11158488.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Strom, C. "FAQ from Mosaic Down Syndrome Society". Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- ^ Borthwick, C. (1996). Racism, IQ and Down's Syndrome. In Disability & Society, Vol 11, No. 3, 1996, pp. 403–410

- ^ a b Bird, G; Thomas, S (2002). "Providing effective speech and language therapy for children with Down syndrome in mainstream settings: A case example". Down Syndrome News and Update. 2 (1): 30–31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Also, Kumin, Libby (1998). "Comprehensive speech and language treatment for infants, toddlers, and children with Down syndrome". In Hassold, TJ; Patterson, D (ed.). Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together. New York: Wiley-Liss.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Development of Fine Motor Skills in Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ Bruni M. "Occupational Therapy and the Child with Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ^ Menéndez, M (2005). "Down syndrome, Alzheimer's disease and seizures". Brain & development. 27 (4): 246–52. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2004.07.008. PMID 15862185.

- ^ a b Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Yang, Q; Rasmussen, SA; Friedman, JM (2002). "Mortality associated with Down's syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study". Lancet. 359 (9311): 1019–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08092-3. PMID 11937181.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b ACOG Guidelines Bulletin #77 clearly state that the sensitivity of the Quad Test is 81%

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Richard Urbano (9 September 2010). Health Issues Among Persons With Down Syndrome. Academic Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-12-374477-7. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Zipursky, A (2003). "Transient leukaemia--a benign form of leukaemia in newborn infants with trisomy 21". British journal of haematology. 120 (6): 930–38. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04229.x. PMID 12648061.

- ^ Hasle, H; Clemmensen, IH; Mikkelsen, M (2000). "Risks of leukaemia and solid tumours in individuals with Down's syndrome". Lancet. 355 (9199): 165–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05264-2. PMID 10675114.

- ^ Karlsson, B; Gustafsson, J; Hedov, G; Ivarsson, SA; Annerén, G (1998). "Thyroid dysfunction in Down's syndrome: relation to age and thyroid autoimmunity". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 79 (3): 242–45. doi:10.1136/adc.79.3.242. PMC 1717691. PMID 9875020.

- ^ Ikeda, K; Goto, S (1986). "Additional anomalies in Hirschsprung's disease: an analysis based on the nationwide survey in Japan". Zeitschrift fur Kinderchirurgie : organ der Deutschen, der Schweizerischen und der Osterreichischen Gesellschaft fur Kinderchirurgie = Surgery in infancy and childhood. 41 (5): 279–81. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1043359. PMID 2947399.

- ^ Zachor, DA; Mroczek-Musulman, E; Brown, P (2000). "Prevalence of celiac disease in Down syndrome in the United States". Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 31 (3): 275–79. doi:10.1097/00005176-200009000-00014. PMID 10997372.

- ^ a b Hsiang, YH; Berkovitz, GD; Bland, GL; Migeon, CJ; Warren, AC (1987). "Gonadal function in patients with Down syndrome". Am. J. Med. Genet. 27 (2): 449–58. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320270223. PMID 2955699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johannisson, R; Gropp, A; Winking, H; Coerdt, W; Rehder, H; Schwinger, E (1983). "Down's syndrome in the male. Reproductive pathology and meiotic studies". Human Genetics. 63 (2): 132–38. doi:10.1007/BF00291532. PMID 6220959.

- ^ Sheridan R, Llerena J, Matkins S, Debenham P, Cawood A, Bobrow M (1989). "Fertility in a male with trisomy 21". J Med Genet. 26 (5): 294–98. doi:10.1136/jmg.26.5.294. PMC 1015594. PMID 2567354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pradhan, M; Dalal, A; Khan, F; Agrawal, S (2006). "Fertility in men with Down syndrome: a case report". Fertil Steril. 86 (6): 1765.e1–3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.03.071. PMID 17094988.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Caputo, AR; Wagner, RS; Reynolds, DR; Guo, SQ; Goel, AK (1989). "Down syndrome. Clinical review of ocular features". Clinical pediatrics. 28 (8): 355–58. doi:10.1177/000992288902800804. PMID 2527102.

- ^ a b Weijerman ME, de Winter JP. Clinical practice: The care of children with Down syndrome. European journal of pediatric. 2010;169:1445–1452.

- ^ a b c Sheehan PZ, Hans PS. UK and Ireland experience of bone anchored hearing aids (BAHA) in individuals with Down Syndrome. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2006; 70, 981-986.

- ^ a b c Porter H, Tharpe AM. Hearing loss among persons with Down syndrome. Int Rev Res Mental Retardation. 2010; 39, 195-220

- ^ Shott, SR; Joseph, A; Heithaus, D (2001). "Hearing loss in children with Down syndrome". Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 61 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1016/S0165-5876(01)00572-9. PMID 11700189.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Shott SR, Joseph A, Heithaus D (2001). "Hearing loss in children with Down syndrome". International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 61 (3): 199–205.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Balkany T.J., Mischke R.E., Downs M.P., Jafek B.W. (1979). "Ossicular abnormalities in Down's syndrome". Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 87: 372–384.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pueschel, SM; Scola, FH (1987). "Atlantoaxial instability in individuals with Down syndrome: epidemiologic, radiographic, and clinical studies". Pediatrics. 80 (4): 555–60. PMID 2958770.

- ^ Rong Mao, X Wang, EL Spitznagel, LP Frelin, JC Ting, H Ding, J Kim, I Ruczinski, TJ Downey, J Pevsner (2005). "Primary and secondary transcriptional effects in the developing human Down syndrome brain and heart". Genome Biology. 6 (13): R107. doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-13-r107. PMC 1414106. PMID 16420667.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ See Leshin, L. (2003). "Trisomy 21: The Story of Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2006-05-21.

- ^ Zohra Rahmani, Jean-Louis Blouin, Nicole Créau-Goldberg, Paul C. Watkins, Jean-François Mattei, Marc Poissonnier, Marguerite Prieur, Zoubida Chettouh, Annie Nicole, Alain Aurias, Pierre-Marie Sinet, Jean-Maurice Delabar (2005). "Down syndrome critical region around D21S55 on proximal 21q22.3". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 37 (S7): 98–103. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320370720. PMID 2149984.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ For a description of human karyotype see Mittleman, A (editor) (1995). "An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomeclature". Retrieved 2006-06-04.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c "Down syndrome occurrence rates (NIH)". Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ^ Mosaic Down syndrome on the Web.

- ^ International Mosaic Down syndrome Association.

- ^ "Genetics of Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2011-05-29.

- ^ "New Recommendations for Down Syndrome Call for Offering Screening to All Pregnant Women". ACOG. 2012-12-20. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008). "CG62: Antenatal care". London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ ACOG Guidelines Bulletin #77 state that the sensitivity of the Combined Test is 82-87%

- ^ NIH FASTER study (NEJM 2005 (353):2001). See also JL Simpson's editorial (NEJM 2005 (353):19).

- ^ For a current estimate of rates, see Benn, PA; Ying, J; Beazoglou, T; Egan, JF (2001). "Estimates for the sensitivity and false-positive rates for second trimester serum screening for Down syndrome and trisomy 18 with adjustment for cross-identification and double-positive results". Prenat. Diagn. 21 (1): 46–51. doi:10.1002/1097-0223(200101)21:1<46::AID-PD984>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 11180240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ACOG Guidelines Bulletin #77 state that the sensitivity of the Integrated Test is 94–96%

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14672489, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14672489instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11728540, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11728540instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10551789, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10551789instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22696388, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22696388instead. - ^ a b Noninvasive Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Aneuploidy Using Cell-Free Fetal Nucleic Acids in Maternal Blood: Clinical Policy (Effective 05/01/2013) from Oxford Health Plans

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt001, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/humupd/dmt001instead. - ^ Committee: Peter Benn, Antoni Borrell, Howard Cuckle, Lorraine Dugoff, Susan Gross, Jo-Ann Johnson, Ron Maymon, Anthony Odibo, Peter Schielen, Kevin Spencer, Dave Wright and Yuval Yaron (October 24, 2011). "Prenatal Detection of Down Syndrome using Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS): a rapid response statement from a committee on behalf of the Board of the International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis" (PDF). ISPD rapid response statement. Charlottesville, VA: International Society for Prenatal Diagnosis. Retrieved October 25, 2011Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Society 'more positive on Down's'". BBC News. 2008-11-24.

- ^ Horrocks Peter (2008-12-05). "Changing attitudes?". BBC News.

- ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/fn.87.3.F220, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/fn.87.3.F220instead. [1] - ^ Down's syndrome monitoring by the BMJ Group. In turn citing: Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1605, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1542/peds.2011-1605instead. - ^ Olbrisch RR (1982). "Plastic surgical management of children with Down syndrome: indications and results". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 35 (2): 195–200. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(82)90163-1. PMID 6211206.

- ^ Parens E (editor) (2006). Surgically Shaping Children : Technology, Ethics, and the Pursuit of Normality. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8305-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Klaiman, P and Arndt, E (1989). "Facial reconstruction in Down syndrome: perceptions of the results by parents and normal adolescents". Cleft Palate Journal. 26 (3): 186–90, discussion 190–92. PMID 2527096.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Also, see Arndt EM, Lefebvre, A; Travis, F; Munro, IR (1986). "Fact and fantasy: psychosocial consequences of facial surgery in 24 Down syndrome children". Br J Plast Surg. 39 (4): 498–504. doi:10.1016/0007-1226(86)90120-7. PMID 2946342.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ SA Pensler; Pensler, JM (1990). "The efficacy of tongue resection in treatment of symptomatic macroglossia in the child". Ann Plast Surg. 25 (1): 14–17. doi:10.1097/00000637-199007000-00003. PMID 2143060.See also Van Lierde KM, Vermeersch H, Van Borsel J, Van Cauwenberge P (2002/2003). "The impact of a partial glossectomy on articulation and speech intelligibility". Oto-Rhino-Laryngologia Nova. 12 (6): 305–10. doi:10.1159/000083122.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Leshin, L (2000). "Plastic Surgery in Children with Down Syndrome". Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- ^ National Down Syndrome Society. "Position Statement on Cosmetic Surgery for Children with Down Syndrome". Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ^ Roberts, JE; Price, J; Malkin, C (2007). "Language and communication development in Down syndrome". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 13 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20136. PMID 17326116.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armstrong SE. "Inclusion: Educating Students with Down Syndrome with Their Non-Disabled Peers". Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2006-05-12. Also, see Bosworth Debra L. "Benefits to Students with Down Syndrome in the Inclusion Classroom: K-3". Retrieved 2006-06-12.[dead link] Finally, see a survey by NDSS on inclusion, Wolpert Gloria (1996). "The Educational Challenges Inclusion Study". National Down Syndrome Society. Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. Retrieved 2006-06-28.

- ^ Lozano, R (2012 Dec 15). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Huether, CA; Ivanovich, J; Goodwin, BS; Krivchenia, EL; Hertzberg, VS; Edmonds, LD; May, DS; Priest, J H (1998). "Maternal age specific risk rate estimates for Down syndrome among live births in whites and other races from Ohio and metropolitan Atlanta, 1970–1989". J Med Genet. 35 (6): 482–90. doi:10.1136/jmg.35.6.482. PMC 1051343. PMID 9643290.

- ^ Estimate from "National Down Syndrome Center". Retrieved 2006-04-21.

- ^ "Prevalence and Incidence of Down Syndrome". Diseases Center-Down Syndrome. Adviware Pty Ltd. 2008-02-04. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

incidence increases ... especially when ... the father is older than age 42

- ^ Warner, Jennifer. "Dad's Age Raises Down Syndrome Risk, Too", "WebMD Medical News". Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Down, JLH (1866). "Observations on an ethnic classification of idiots". Clinical Lecture Reports, London Hospital. 3: 259–62. Retrieved 2006-07-14. For a history of the condition, see Conor, WO (1998). John Langdon Down, 1828–1896. Royal Society of Medicine Press. ISBN 1-85315-374-5. or Conor, Ward. "John Langdon Down and Down's syndrome (1828–1896)". Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. Retrieved 2006-06-02.

- ^ a b Howard-Jones, Norman (1979). "On the diagnostic term "Down's disease"". Medical History. 23 (1): 102–04. PMC 1082401. PMID 153994.

- ^ a b David Wright (25 August 2011). Downs:The history of a disability: The history of a disability. Oxford University Press. pp. 104–108. ISBN 978-0-19-956793-5. Retrieved 25 August 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Wright2011" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Warkany, J (1971). Congenital Malformations. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, Inc. pp. 313–14. ISBN 0-8151-9098-0.

- ^ Lejeune, J; Gautier, M; Turpin, R (1959). "Etude des chromosomes somatiques de neuf enfants mongoliens". Comptes Rendus Hebd Seances Acad Sci. 248 (11): 1721–22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gordon, Allen (1961). "Mongolism (Correspondence)". The Lancet. 1 (7180): 775.

- ^ Syndrome (Name Change) from Mongoloid-Charter Document filed by Kay McGee

- ^ A planning meeting was held on 20 March 1974, resulting in a letter to The Lancet."Classification and nomenclature of malformation (Discussion)". The Lancet. 303 (7861): 798. 1974. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(74)92858-X. PMID 4132724. The conference was held 10–11 February 1975, and reported to The Lancet shortly afterward."Classification and nomenclature of morphological defects (Discussion)". The Lancet. 305 (7905): 513. 1975. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(75)92847-0. PMID 46972.

- ^ Leshin, Len (2003). "What's in a name". Retrieved 2006-05-12.

- ^ Inclusion. National Down Syndrome Society. Archived from the original on 2008-06-08. Retrieved 2006-05-21.

- ^ Timeline-Key dates in Mencap's history

- ^ NADS Honors our Founder: Kay McGee

- ^ National Down Syndrome Congress - History

- ^ NDSS History

- ^ a b http://www.ndss.org/About-NDSS/NDSS-History/#sthash.iYHmLQ83.dpuf

- ^ Green, RM (1997). "Parental autonomy and the obligation not to harm one's child genetically". J Law Med Ethics. 25 (1): 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.1997.tb01389.x. PMID 11066476.

- ^ Rayner, Clare (27 June 1995). "ANOTHER VIEW: A duty to choose unselfishly". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ^ Glover NM and Glover SJ (1996). "Ethical and legal issues regarding selective abortion of fetuses with Down syndrome". Ment. Retard. 34 (4): 207–14. PMID 8828339.

- ^ Will, George (2005-04-01). "Eugenics By Abortion: Is perfection an entitlement?". Washington Post: A37.

- ^ Will, George (May 2, 2012). "Jon Will's gift". Washington Post.

- ^ "Letter: Ghost of eugenics stalks Down's babies | Independent, The (London) | Find Articles at BNET.com".

- ^ "New Eugenics and the newborn: The historical "cousinage" of eugenics and infanticide, The". Ethics & Medicine. 2003.

- ^ Erik Parens and Adrienne Asch (2003). "Disability rights critique of prenatal genetic testing: Reflections and recommendations". Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 9 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10056. PMID 12587137. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

- ^ Singer, Peter (1993). "Taking Life: Humans". Practical ethics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 395. ISBN 0-521-43971-X.

- ^ National Down Syndrome Society[dead link]

- ^ Down Syndrome South Africa.

- ^ DSIAM—Down Syndrome in Arts & Media website. Retrieved 02-18-10.

- ^ "Dr. Karen Gaffney: First living person with Down syndrome to receive honorary doctorate". Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ Ginnsz, Stephane. "Film Actor with Down syndrome". ginnsz.com. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ "Disabled woman who fought for transplant dies - SF Gate". Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Osborn, Michael (2007-08-31). "Haddon Debut Captures Teen Crisis". BBC. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Down's actor tackles Hamlet". This is Cornwall. 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ "Up Syndrome on the Internet Movie Database". Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ "Friends on Both Sides of Film". Retrieved 2001-04-27. from the Corpus-Christi Caller Times

- ^ Lomon, Chris (2003-02-28). "NHL Alumni RBC All-Star Awards Dinner". NHL Alumni. Archived from the original on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ "Yo También on the Internet Movie Database". Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ "Pujols Family Foundation Home Page". Retrieved 2006-12-08.[dead link]

- ^ "Special Olympic Athlete Stars in Movie". Retrieved 2007-11-05.[dead link]

- ^ "Bratislava International Film festival 2004". Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ "Judith Scott: Finding a Voice". Retrieved 2012-03-03.

- ^ http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=it&u=http://pasquinoweb.wordpress.com/2011/03/22/crederci-io-sono-giusi-giusi-spagnolo/&ei=TghRTtCzHY2%7CSgQfetOSIBw&sa=X&oi=translate&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CB8Q7gEwAA&prev=/search%3Fq%3D%2522giusi%2Bspagnolo%2522%26hl%3Den%26biw%3D1525%26bih%3D684%26prmd%3%7CDivnso

- ^ http://www.lottimista.com/2011/04/18/giusi-spagnolo-la-prima-laureata-down-d%E2%80%99italia/

References

- Arron, JR; Winslow, MM; Polleri A (2006). "NFAT dysregulation by increased dosage of DSCR1 and DYRK1A on chromosome 21". Nature. 441 (7093): 595–600. doi:10.1038/nature04678. PMID 16554754.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Epstein CJ (2006). "Down's syndrome: critical genes in a critical region". Nature. 441 (7093): 582–83. doi:10.1038/441582a. PMID 16738647.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ganong, WJ (2005). Review of Medical Physiology (21st ed.). New York: Mc-Graw Hill. ISBN 0-07-140236-5.

- Nelson, DL; Gibbs, RA (2004). "Genetics. The critical region in trisomy 21". Science. 306 (5696): 619–21. doi:10.1126/science.1105226. PMID 15499000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Olson, LE; Richtsmeier, JT; Leszl, J; Reeves, RH (2004). "A chromosome 21 critical region does not cause specific Down syndrome phenotypes". Science. 306 (5696): 687–90. doi:10.1126/science.1098992. PMID 15499018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hattori, M; Fujiyama, A; Taylor, TD (2000). "The DNA sequence of human chromosome 21". Nature. 405 (6784): 311–19. doi:10.1038/35012518. PMID 10830953.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Underwood, JCE (2004). General and Systematic Pathology (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-07334-1.

- Beck, MN (1999). Expecting Adam. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 0-425-17448-4.

- Buckley, S (2000). Living with Down Syndrome. Portsmouth, UK: The Down Syndrome Educational Trust. ISBN 1-903806-01-1.

- Down's Syndrome Research Foundation (2005). Bright Beginnings: A Guide for New Parents (PDF). Buckinghamshire, UK: Down's Syndrome Research Foundation.

- Dykens EM (2007). "Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in persons with Down syndrome". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 13 (3): 272–78. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20159. PMID 17910080.

- Hassold, TJ; Patterson, D eds. (1999). Down Syndrome: A Promising Future, Together. New York: Wiley Liss.

- Kingsley, J (1994). Count Us In: Growing up with Down Syndrome. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. ISBN 0-15-622660-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Koch, Richard; De La Cruz, Felix F, eds. (1975). Downs Syndrome...: Research, Prevention and Management. Proceedings of a Conference on Down's Syndrome. New York: Brunner/Mazel. ISBN 0-87630-093-X.

- Pueschel, SM; Sustrova, M eds. (1997). Adolescents with Down Syndrome: Toward a More Fulfilling Life. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Paul H

- Selikowitz, M (1997). Down Syndrome: The Facts (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262662-0.

- Van Dyke, DC (1995). Medical and Surgical Care for Children with Down Syndrome. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House. ISBN 0-933149-54-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Zuckoff, M (2002). Choosing Naia: A Family's Journey. New York: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-2817-7.

External links

- Facts about Down Syndrome from the National Institutes of Health

- Tying Your Own Shoes An animated documentary that provides insight into the lives of four adult artists with Down Syndrome, by National Film Board of Canada