Twilight Zone: The Movie

| Twilight Zone: The Movie | |

|---|---|

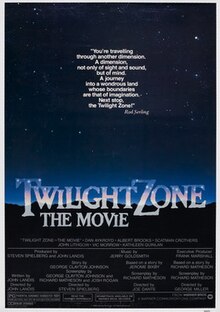

Original 1983 theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | John Landis (prologue and "Time Out" segment) Steven Spielberg ("Kick the Can" segment) Joe Dante ("It's a Good Life" segment) George Miller ("Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" segment) |

| Written by | John Landis (prologue and segment 1) George Clayton Johnson (original screenplay 'Kick the Can', segment 2) Richard Matheson and Melissa Mathison (segment 2) Jerome Bixby (story 'It's a Good Life', segment 3) Richard Matheson (segment 3) Richard Matheson (short story 'Nightmare at 20,000 Feet' and screenplay, segment 4) |

| Produced by | Steven Spielberg John Landis |

| Starring | Dan Aykroyd Albert Brooks Scatman Crothers John Lithgow Vic Morrow Kathleen Quinlan |

| Narrated by | Burgess Meredith Rod Serling |

| Cinematography | Allen Daviau John Hora Stevan Larner |

| Edited by | Malcolm Campbell Tina Hirsch Michael Kahn Howard E. Smith |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million |

| Box office | $29,450,919 |

Twilight Zone: The Movie is a 1983 anthology fantasy-science fiction horror film produced by Steven Spielberg and John Landis as a theatrical version of The Twilight Zone, a 1959 and '60s TV series created by Rod Serling. The film stars Vic Morrow, Scatman Crothers, Kathleen Quinlan and John Lithgow with Dan Aykroyd and Albert Brooks in the prologue segment. Burgess Meredith, who starred in four episodes of the original series, took on Serling's position as narrator. Unlike Serling, he did not appear on screen, nor did he receive screen credit, though his name appears in the end credits. In addition to Meredith, five actors from the original series (William Schallert, Kevin McCarthy, Bill Mumy, Murray Matheson and Patricia Barry) had roles in the film.

The film is a remake of three classic episodes of the original series and includes one original story. Landis directed the prologue and the first segment, Steven Spielberg directed the second, Joe Dante the third, and George Miller directed the final segment. Dante recalled that in the film's original conception the three stories would be interwoven with characters from one segment would appear in another segment, but later problems with the film precluded this.[1]

The film garnered notoriety before its release for the tragic stunt helicopter crash which took the lives of Vic Morrow and two child actors, Myca Dinh Le and Renee Shin-Yi Chen, during the filming of the segment directed by Landis. The two child actors were hired illegally.[2] Their deaths led to a high-profile legal case, although at the end of the trial no one was found to be criminally culpable for the accident.[3] Because of this incident, this was Vic Morrow's final film.

Plot summaries

Prologue

The film starts with a driver (Albert Brooks) and his passenger (Dan Aykroyd) driving very late at night, singing along to Creedence Clearwater Revival's cover of "Midnight Special" on a cassette, and the song ends when the tape breaks. The driver talks about a scary game he finds amusing: he switches off the car's headlights and drives in the dark. After the passenger admits he's uncomfortable, the driver laughs it off and keeps the lights on. With no tape or radio, the pair start a Name That Tune game with television theme songs such as Sea Hunt and Hawaii Five-O, and eventually the classic theme to The Twilight Zone. The conversation turns to what episodes of the series they found most scary, such as Burgess Meredith in "Time Enough at Last" and other classics. The passenger then asks the driver, "Do you want to see something really scary?" The driver obliges and reluctantly pulls over. The passenger turns his face away, then turns back around having transformed into a demon and attacks the driver.

The scene then cuts to outside the car as the familiar Twilight Zone opening theme music and monologue begin (spoken by narrator Burgess Meredith):

You unlock this door with the key of imagination. Beyond it is another dimension. A dimension of sound. A dimension of sight. A dimension of mind. You're moving into a land of both shadow and substance of things and ideas. You've just crossed over into... The Twilight Zone.

Cast

- Burgess Meredith - Narrator

- Dan Aykroyd - Passenger

- Albert Brooks - Car Driver

Time Out

The film's only original segment was the first, directed by John Landis. It is loosely based on the original Twilight Zone episode "A Quality of Mercy", with the opening narration borrowing from "What You Need" and "A Nice Place to Visit". The narrator starts with this monologue:

You're about to meet an angry man: Mr. William Connor, who carries on his shoulder a chip the size of the national debt. This is a sour man, a lonely man, who's tired of waiting for the breaks that come to others, but never to him. Mr. William Connor, whose own blind hatred is about to catapult him into the darkest corner of the Twilight Zone.

Bill Connor (Vic Morrow) is an outspoken bigot who is bitter after being passed over for a promotion. Drinking in a bar after work with his friends, Bill makes prejudiced remarks and racial slurs towards Jews, blacks and Asians, attracting the attention of a group of black men sitting near them who strongly resent his racist comments. Bill leaves the bar very angry, but when he walks outside, the supernatural tone begins.

He inexplicably proceeds to assume the racial ethnicities of people against whom he was always prejudiced.

First, he finds himself in occupied France during World War II. He is spotted by a pair of SS officers patrolling the streets, who see him as a Jewish man. A chase ensues around the city, and Bill is shot in his arm by one of the German officers.

Bill falls from the ledge of a building and abruptly finds himself in the rural South during the 1940s. There a group of Ku Klux Klansmen (including John Larroquette) sees him as an African American whom they are about to lynch. Bill is scared and confused; he vehemently tells them he is white.

While trying to escape the Klansmen, he suddenly finds himself in a jungle during the Vietnam War, as a Vietnamese man is blown to bits by U.S. soldiers.

Instead of killing him, the grenade thrown by the soldiers blasts him into occupied France again. There he is captured by Nazi soldiers and put into an enclosed railroad freight car, along with other Jewish Holocaust prisoners. With no apparent possibility of redemption or rescue, Bill sees and uselessly screams for help to his friends from the bar, who have come out to the parking lot and cannot hear his cries, nor see him or the train as it pulls away to a concentration camp, thus leaving them to wonder about his whereabouts and the viewer to wonder about his fate.

Cast

- Burgess Meredith - Narrator

- Vic Morrow - Bill Connor

- Doug McGrath - Larry

- Charles Hallahan - Ray

- Rainer Peets - German Officer 1

- Kai Wulff - German Officer 2

- Sue Dugan - Waitress No. 1

- Debby Porter - Waitress No. 2

- Steven Williams - Bar Patron

- Annette Claudier - French Monther

- Joseph Hieu - Vietnamese

- Al Leong - Vietnamese

- Stephen Bishop - Charming G.I.[4]

- Thomas Byrd 0 G.I.

- Vincent J. Isaac 0 G.I.

- Bill Taylor 0 G.I.

- William S. Taylor - G.I.

- Domingo Ambriz - G.I.

- Eddy Donno - Ku Klux Klan Member

- Michael Milgrom - Ku Klux Klan Member

- John Larroquette - Ku Klux Klan Member

- Norbert Weisser - Soldier No. 1

Kick the Can

The second segment was directed by Steven Spielberg and is a remake of the episode "Kick the Can." The narrator starts with this monologue:

It is sometimes said that where there is no hope, there is no life. Case in point: the residents of Sunnyvale Rest Home, where hope is just a memory. But hope just checked into Sunnyvale, disguised as an elderly optimist, who carries his magic in a shiny tin can.

An old man named Mr. Bloom (Scatman Crothers) has just moved into Sunnyvale Retirement Home. Upon his arrival, he sits around kindly and smiles as he listens to the other elders reminisce about the joys they experienced in their youth. Mr. Bloom implies to them just because they are old does not mean they cannot enjoy life anymore, and that feeling young and active has to do with your attitude, not your age. He tells them that later that night, he will wake them and that they can join him in a game of kick the can. All agree; however, Leo Conroy (Bill Quinn) disagrees, saying that now that they are all old they cannot engage in physical activity and play the games they once did as children.

That night, Mr. Bloom gathers the rest of the optimistic residents outside and plays the game, during which they are transformed into childhood versions of themselves. Although they are extremely ecstatic to be young again and engage in the activities they once enjoyed so long ago, they also realize that being young again means you not only experience the good aspects of life again but also the bad. They request to be old again, which Mr. Bloom grants to them. Leo Conroy witnesses one resident, Mr. Agee (Murray Matheson, who had a role in "Five Characters in Search of an Exit") that still remains young, and says that he wants to go with him before the boy runs off. Conroy realizes that he does not have to stop enjoying life because of his old age.

The segment ends with Mr. Bloom leaving to another retirement home, and Conroy outside happily kicking a can around the yard, having learned being young at heart is what really matters.

Cast

- Burgess Meredith - Narrator

- Scatman Crothers - Mr. Bloom

- Bill Quinn - Leo Conroy

- Martin Garner - Mr. Weinstein

- Selma Diamond - Mrs. Weinstein

- Helen Shaw - Mrs. Dempsey

- Murray Matheson - Mr. Agee

- Peter Brocco - Mr. Mute

- Priscilla Pointer - Miss Cox

- Scott Nemes - Young Mr. Weinstein

- Tanya Fenmore - Young Mrs. Weinstein

- Evan Richards - Young Mr. Agee

- Laura Mooney - Young Mrs. Dempsey

- Christopher Eisenmann - Young Mr. Mute

- Richard Swingler - Mr. Gray Panther

- Alan Haufrect - Mr. Conroy's Son

- Cheryl Socher - Mr. Conroy's Daughter-in-Law

- Elsa Raven - Nurse No. 2

It's a Good Life

The third segment, a remake of the episode "It's a Good Life," was directed by Joe Dante. Its opening narration is borrowed, in part, from "Night Call." The name of the main character Helen Foley is from the original series episode "Nightmare as a Child" The narrator starts with this monologue:

Portrait of a woman in transit: Helen Foley, age 27. Occupation: schoolteacher. Up until now, the pattern of her life has been one of unrelenting sameness, waiting for something different to happen. Helen Foley doesn't know it yet, but her waiting has just ended.

Mild-mannered Helen Foley (Kathleen Quinlan), traveling to a new job, visits a rural bar for directions. While talking to the owner Walter Paisley (Dick Miller), she witnesses Anthony, a young boy (Jeremy Licht) playing an arcade game, who is being blamed by a pair of locals (one of whom portrayed Anthony in the original episode, Bill Mumy) for "accidentally" causing interference on the TV by slapping the side of the game machine. When one of the men pushes Anthony away from the game and pulls the plug, Helen comes to the boy's defense, but Anthony runs out of the restaurant. As Helen leaves, she backs into the boy with her car in the parking lot, damaging his bicycle. Helen offers Anthony a ride home.

They eventually arrive at Anthony's house, which is an immense home in the country. When Helen arrives, she meets Anthony's family: Uncle Walt (Kevin McCarthy, who starred in "Long Live Walter Jameson"); sister Ethel (Nancy Cartwright); and Anthony and Ethel's mother (Patricia Barry, who starred in "I Dream of Genie" and "The Chaser") and father (William Schallert, who played a role in "Mr. Bevis"). Anthony's family seems overly welcoming, but Helen at first dismisses this. Anthony starts to show Helen around the house (while the family rifles through Helen's purse and coat); there is a television set in every room showing cartoons. She loses Anthony and comes to the room of another sister, Sara (Cherie Currie). Helen calls out to the girl, who is in a wheelchair and watching a television displaying cartoons, and gets no response. Anthony appears and explains that Sara had been in an accident; Helen isn't able to see that the girl has no mouth.

After the tour, Anthony announces that it is time for dinner, which consists of Anthony's favorite foods: including ice cream, candy apples, and hamburgers topped with peanut butter. Confused at first at how the family eats, Helen thinks that this is a birthday dinner for Anthony. Ethel complains at the prospect of another birthday; Anthony glares at her, and her plate flies out of her hands onto the ground. Helen hurredly attempts to leave, but Anthony urges Helen to stay and see Uncle Walt's "hat trick". Helen is stunned to see that a top hat has suddenly appeared on top of the television set. Uncle Walt is very nervous about what could be in the hat, but he pulls an ordinary rabbit out of it. The family members are relieved, but Anthony insists on more, and a large, cartoonish rabbit springs from the hat. Helen screams, and Anthony orders it to go away. As she attempts to flee, she falls and spills the contents of her purse, and Anthony finds a note slipped in from one of the Fremonts stating "Help us! Anthony is a monster!" When the family points the finger at Ethel, Anthony wills her into the television set where she is eaten by a large dragon-like cartoon character.

Helen attempts to escape only to have the door open up to a human eye. She closes it quickly only to see Anthony at the top of the stairs pleading her to stay. She then is led back into the room to see Anthony with a demonic creature, which she demands to disappear. In a fit of irritation, Anthony makes the entire house disappear, and his family with it, leaving himself and Helen literally nowhere. Anthony explains that, since they were not happy living with him anymore, he sent them all back where they came from. Now, at last, Anthony realizes the horrific loneliness that comes with being omnipotent. For once, he expresses the tremendous insecurity and pain that seethes within him instead of burying it.

Helen offers to be Anthony's teacher, and also his student. Together, she says, they can find uses for his power that even he never dreamed of. Having been confronted with the true end results of his reign of terror, Anthony welcomes Helen's offer and makes her car reappear. Both ride off toward her new home and job, surrounded by bright meadows filled with flowers.

Cast

- Burgess Meredith - Narrator

- Kathleen Quinlan - Helen Foley

- Jeremy Licht - Anthony

- Kevin McCarthy - Uncle Walt

- Patricia Barry - Mother

- William Schallert - Father

- Nancy Cartwright - Ethel

- Dick Miller - Walter Paisley

- Cherie Currie - Sara

- Bill Mumy - Tim

- Jeffrey Bannister - Charlie

Nightmare at 20,000 Feet

The fourth segment is a remake of the episode "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet", directed by George Miller. Its opening narration is borrowed, in part, from "In His Image." The narrator starts with this monologue:

What you're looking at could be the end of a particularly terrifying nightmare. It isn't. It's the beginning. Introducing Mr. John Valentine, air traveller. His destination: the Twilight Zone.

Nervous airline passenger Mr. John Valentine (John Lithgow) is in an airplane lavatory as he tries to recover from what seems to be a panic attack. The flight attendants attempt to coax Mr. Valentine from the lavatory, and they repeatedly assure him that everything is going to be all right, but his nerves and antics disturb the surrounding passengers.

As Mr. Valentine takes his seat, he notices a hideous gremlin (Larry Cedar) on the wing of the plane and begins to spiral into another severe panic. He watches as the creature wreaks havoc on the wing, damaging the plane's engine, losing more control each time he sees it do something new. Valentine finally snaps, grabs a hand gun from a sleeping airplane security guard, breaks the window with a fire extinguisher (causing a breach in the pressurized cabin), and begins firing at the gremlin. This only serves to catch the attention of the gremlin, who rushes up to Valentine and promptly destroys the gun. After a tense moment, in which they notice that the plane is landing, the gremlin grabs Valentine's face, then simply scolds him by wagging its finger in his face. The creature leaps into the sky as the airplane begins its emergency landing.

On the ground as a straitjacketed Valentine is carried off in an ambulance claiming to be a hero, the police, crew and passengers begin to discuss the incident writing off Valentine as insane. However, the aircraft maintenance crew soon arrives and everyone gathers to examine the unexplained damage to the plane's engines complete with claw marks.

Cast

- Burgess Meredith - Narrator

- John Lithgow - John Valentine

- Abbe Lane - Sr. Stewardess

- Donna Dixon - Jr. Stewardess

- John Dennis Johnston - Co-Pilot

- Larry Cedar - Gremlin

- Charles Knapp - Air Marshal

- Byron McFarland - Pilot Announcement

- Christina Nigra - Little Girl who killed edward

- Lana Schwab - Mother

- Margaret Wheeler - Old Woman

- Eduard Franz - Old Man

- Margaret Fitzgerald - Young Girl

- Jeffrey Weissman - Young Man

- Jeffrey Lampert - Mechanic

- Frank Toth - Mechanic

- Carol Serling - Mechanic

Epilogue

The fourth segment ends with a scene reminiscent of the prologue. Valentine is in an ambulance when the driver (Dan Aykroyd) starts playing Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Midnight Special". The driver turns and says "Heard you had a big scare up there, huh? Wanna see something really scary?" Valentine's eyes widen as the ambulance continues driving. The scene fades out to a starry night sky accompanied by Rod Serling's opening monologue from the first season of The Twilight Zone:

There is a fifth dimension, beyond that which is known to man. It is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition, and it lies between the pit of man's fears and the summit of his knowledge. This is the dimension of imagination. It is an area which we call the Twilight Zone.

Cast

- John Lithgow - John Valentine

- Dan Aykroyd - Ambulance Driver

Helicopter accident

During the filming of the "Time Out" segment directed by John Landis on July 23, 1982 at around 2:30 a.m., actor Vic Morrow and child actors Myca Dinh Le (age 7) and Renee Shin-Yi Chen (陳欣怡,[5] age 6) died in an accident involving a helicopter being used on the set. The two child actors were hired in violation of California law, which prohibits child actors from working at night or in proximity to explosions, and requires the presence of a teacher/social worker. During the subsequent trial, the illegality of the children's hiring was admitted by the defense, with Landis admitting culpability for that (but not the accident), and admitting that their hiring was "wrong."[2]

In the scene that served as the original ending, Morrow's character was to have traveled back through time again and stumbled into a deserted Vietnamese village where he finds two young Vietnamese children left behind when a U.S. Army helicopter appears and begins shooting at them. Morrow was to take both children under his arms and escape out of the village as the hovering helicopter destroyed the village with multiple explosions which would have led to his character's redemption. The helicopter pilot had trouble navigating through the fireballs created by pyrotechnic effects for the sequence. A technician didn't know this and detonated two of the pyrotechnic charges close together. The explosions caused the low-flying helicopter to spin out of control and crash land on top of Morrow and the two children as they were crossing a small pond away from the village mock-up. All three were killed instantly; Morrow and Myca were decapitated and mutilated by the helicopter's top rotor blades while Renee was crushed by one of the skids.[6]

The probable cause of the accident was the detonation of debris-laden high-temperature special effects explosions too near a low-flying helicopter leading to foreign object damage to one rotor blade and delamination due to heat to the other rotor blade, the separation of the helicopter's tail rotor assembly, and the uncontrolled descent of the helicopter. The proximity of the helicopter (around 25 feet off the ground) to the special effects explosions was due to the failure to establish direct communications and coordination between the pilot, who was in command of the helicopter operation, and the film director, who was in charge of the filming operation.[7]

The deaths were recorded on film from at least three different camera angles. As a result of Morrow's death, the remaining few scenes of the segment could not be filmed and all of the scenes that were filmed involving the two Vietnamese children, Myca and Renee, were deleted from the final cut of the segment.[8]

Myca and Renee were being paid under the table to circumvent California's child-labor laws. California did not allow children to work at night. Landis opted not to seek a waiver, either because he didn't think he'd get one for such a late hour or because he knew he would never get approval to have young children as part of a scene with a large number of explosives. The casting agents didn't know that the children would be involved in the scene. Associate producer George Folsey, Jr. told the children's parents not to tell any firefighters on set that the children were part of the scene, and also hid them from a fire safety officer who also worked as a welfare worker. A fire safety officer was concerned the blasts would cause a crash, but didn't tell Landis of his concerns.[6][2]

The accident led to civil and criminal action against the filmmakers which lasted nearly a decade. Landis, Folsey, production manager Dan Allingham, pilot Dorcey Wingo and explosives specialist Paul Stewart were tried and acquitted on charges of manslaughter in a nine-month trial in 1986 and 1987.[2][9] As a result of the accident, second assistant director Andy House had his name removed from the credits and replaced with the pseudonym Alan Smithee.[2]

Release and reaction

Twilight Zone: The Movie opened on June 24, 1983 and received mixed to positive reviews. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times rated each segment individually, awarding them (on a scale of four stars): two for the prologue and first segment, one-and-a-half for the second, three-and-a-half stars for the third, and three-and-a-half for the final. Ebert noted that "the surprising thing is, the two superstar directors are thoroughly routed by two less-known directors whose previous credits have been horror and action pictures... Spielberg, who produced the whole project, perhaps sensed that he and Landis had the weakest results, since he assembles the stories in an ascending order of excitement. Twilight Zone starts slow, almost grinds to a halt, and then has a fast comeback."[10] The New York Times' Vincent Canby called the movie a "flabby, mini-minded behemoth."[11]

According to boxofficemojo.com, it opened at #4, grossing $6,614,366 in its opening weekend at 1,275 theaters, averaging $5,188 per theater (adjusting to $15,076,555 and a $11,825 average in 2009). It later expanded to 1,288 theaters and ended up grossing $29,450,919 (adjusting to $67,129,396 in 2009).[12] Having cost $10 million to make, it was not the enormous hit which executives were looking for, but it was still a financial success and it helped stir enough interest for CBS to give the go-ahead to the 1980s TV version of The Twilight Zone.

It was released to LaserDisc and VHS several times, most recently as part of WB's "Hits" line, and was released for DVD, HD DVD and Blu-ray on October 9, 2007.

Novelization

Robert Bloch wrote the book adaptation of Twilight Zone: The Movie. Bloch's order of segments does not match the order in the film itself, as he was given the original screenplay to work with, in which "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" was the second segment, and "Kick the Can" was the fourth. Both the movie's prologue and epilogue are missing in the novelization. Bloch claimed that no one told him the anthology had a wraparound sequence. Bloch also said that in the six weeks he was given to write the book, he only saw a screening of two of the segments; he had to hurriedly change the ending of the first segment, after the helicopter accident that occurred during filming.[13] As originally written, the first segment would have ended as it did in the original screenplay (Connor finds redemption by saving two Vietnamese children whose village is being destroyed by the Air Cavalry). The finished book reflects how the first segment ends in the final cut of the film. it was terible

Soundtrack

Jerry Goldsmith, who scored several episodes of the original series, composed the music for the movie and re-recorded Marius Constant's series theme. The original soundtrack album was released by Warner Bros. Records.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Twilight Zone Main Title" | 0:42 | ||

| 2. | "Overture" | 5:13 | ||

| 3. | "Time Out" | 6:45 | ||

| 4. | "Kick The Can" | 10:12 | ||

| 5. | "Nights Are Forever" | Goldsmith | Jennifer Warnes | 3:39 |

| 6. | "It's A Good Life" | 10:52 | ||

| 7. | "Nightmare At 20,000 Feet" | 6:53 | ||

| 8. | "Twilight Zone End Title" | 0:45 | ||

| Total length: | 45:01 | |||

"Time Out" is the only segment whose music is not included in the overture (actually the film's end title music).

A complete recording of the dramatic score, including a previously-unreleased song by Joseph Williams, was released in April 2009 by Film Score Monthly, representing the soundtrack's first US release on compact disc. Both songs were used in "Time Out" and were produced by Bruce Botnick with James Newton Howard (Howard also arranged "Nights Are Forever"). The promotional song from this movie, "Nights Are Forever", written by Jerry Goldsmith with lyricist John Bettis, and sung by Jennifer Warnes, is heard briefly during the jukebox scene in the opening segment with Vic Morrow.

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Twilight Zone Main Title" | Marius Constant | 0:45 |

| 2. | "Time Out — Time Change/Questions/The Ledge" | 4:51 | |

| 3. | "The K.K.K./Yellow Star" | 3:53 | |

| 4. | "Kick the Can — Harp and Love" | 1:27 | |

| 5. | "Weekend Visit" | 1:34 | |

| 6. | "Kick the Can" | 0:37 | |

| 7. | "Night Games" | 1:53 | |

| 8. | "Young Again/Take Me With You/A New Guest" | 10:10 | |

| 9. | "It's a Good Life — I Remember/The House" | 2:29 | |

| 10. | "The Picture/The Sister/I Didn't Do It" | 1:20 | |

| 11. | "Cartoon Monster" | 3:06 | |

| 12. | "That's All, Ethel" | 1:47 | |

| 13. | "Teach Me/No More Tricks" | 3:54 | |

| 14. | "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet' — Cabin Fever/Nervous Pills" | 2:39 | |

| 15. | "On the Wing" | 1:20 | |

| 16. | "A Face in the Window" | 2:10 | |

| 17. | "Hungry Monster/Engine Failure" | 01:35 | |

| 18. | "Overture (Twilight Zone Theme and End Title)" | 05:55 | |

| 19. | "Nights Are Forever — Jennifer Warnes" | 3:36 | |

| 20. | "Anesthesia — music and lyrics by Joseph Williams and Paul Gordon, performed by Joseph Williams" | 3:02 | |

| 21. | "Time Change/Questions/The Ledge (Time Out: album edit)" | 3:01 | |

| 22. | "Young Again/Take Me With You/A New Guest (Kick the Can: alternate segments)" | 05:01 | |

| 23. | "Cartoon Monster/That's All Ethel (It's a Good Life: album edit)" | 04:29 | |

| 24. | "Cartoon Music (It's a Good Life)" | 01:26 | |

| 25. | "On the Wing/A Face in the Window/Hungry Monster/Twilight Zone Theme (Nightmare at 20,000 Feet: album edit)" | 4:59 | |

| Total length: | 1:16:59 | ||

References

- ^ Joe Dante, 'The Hole' Director On New Horror, '80s Favorites And More 'Gremlins'

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Farber; Marc Green (1988). "Outrageous Conduct: Art, Ego and the Twilight Zone Case". Arbor House (Morrow).

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) [page needed] - ^ Weber, Bruce. "James F. Neal, Litigated Historic Cases, Dies at 81", The New York Times, October 22, 2010. Accessed October 23, 2010.

- ^ http://www.starpulse.com/Actors/Bishop,_Stephen/Biography/

- ^ http://www.findadeath.com/Deceased/m/Vic%20Morrow/reneegrave.JPG

- ^ a b Noe, Denise. The Twilight Zone Tragedy. Crime Library. Accessed 2011-02-09.

- ^ "Aircraft Accident Report" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ Twilight Zone: The Movie

- ^ Feldman, Paul (May 29, 1987). "John Landis Not Guilty in 3 'Twilight Zone' Deaths : Jury Also Exonerates Four Others". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Twilight Zone -- The Movie". Sun Times. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983)". Rottren Tomatoes. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Twilight Zone: The Movie". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ^ Bloch, Robert (1983). Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography. Tor Books. pp. 388–389.

External links

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at IMDb

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at the TCM Movie Database

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at AllMovie

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at Rotten Tomatoes

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at Box Office Mojo

- The Anorak Zone presents... The Twilight Zone

- Twilight Zone: The Movie at Curlie

- NTSB report on the helicopter accident

- Google Earth view of the accident site in Indian Dunes, CA.

- All About the Twilight Zone tragedy by Denise Noe, Crime Library

- 1983 films

- 1983 horror films

- 1980s fantasy films

- 1980s science fiction films

- American science fiction films

- Anthology films

- Aviation films

- American fantasy films

- Dark fantasy films

- Nazis in fiction

- Filmed deaths

- Films based on works by Richard Matheson

- Films based on short fiction

- Films based on television series

- Films directed by John Landis

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Films directed by Joe Dante

- Films directed by George Miller

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Films set on airplanes

- Screenplays by Richard Matheson

- The Twilight Zone (franchise)

- Warner Bros. films

- Film scores by Jerry Goldsmith