Herbicide

Herbicides, also commonly known as weedkillers, are pesticides used to kill unwanted plants.[1] Selective herbicides kill specific targets, while leaving the desired crop relatively unharmed. Some of these act by interfering with the growth of the weed and are often synthetic mimics of natural plant hormones. Herbicides used to clear waste ground, industrial sites, railways and railway embankments are not selective and kill all plant material with which they come into contact. Smaller quantities are used in forestry, pasture systems, and management of areas set aside as wildlife habitat.

Herbicides are widely used in agriculture and landscape turf management. In the US, they account for about 70% of all agricultural pesticide use.[1]

History

Prior to the widespread use of chemical herbicides, cultural controls, such as altering soil pH, salinity, or fertility levels, were used to control weeds. Mechanical control (including tillage) was also (and still is) used to control weeds.

First herbicides

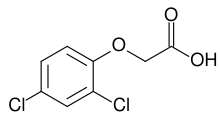

Although research into chemical herbicides began in the early 20th century, the first major breakthrough was the result of research conducted in both the UK and the US during the Second World War into the potential use of agents as biological weapons.[2] The first modern herbicide, 2,4-D, was first discovered and synthesized by W. G. Templeman at Imperial Chemical Industries. In 1940, he showed that "Growth substances applied appropriately would kill certain broad-leaved weeds in cereals without harming the crops." By 1941, his team succeeded in synthesizing the chemical. In the same year, Pokorny in the US achieved this as well.[3]

Independently, a team under Juda Hirsch Quastel, working at the Rothamsted Experimental Stationmade the same discovery. Quastel was tasked by the Agricultural Research Council (ARC) to discover methods for improving crop yield. By analyzing soil as a dynamic system, rather than an inert substance, he was able to apply techniques such as perfusion. Quastel was able to quantify the influence of various plant hormones, inhibitors and other chemicals on the activity of microorganisms in the soil and assess their direct impact on plant growth. While the full work of the unit remained secret, certain discoveries were developed for commercial use after the war, including the 2,4-D compound.[4]

When it was commercially released in 1946, it triggered a worldwide revolution in agricultural output and became the first successful selective herbicide. It allowed for greatly enhanced weed control in wheat, maize (corn), rice, and similar cereal grass crops, because it kills dicots (broadleaf plants), but not most monocots (grasses). The low cost of 2,4-D has led to continued usage today, and it remains one of the most commonly used herbicides in the world. Like other acid herbicides, current formulations use either an amine salt (often trimethylamine) or one of many esters of the parent compound. These are easier to handle than the acid.

Further discoveries

The triazine family of herbicides, which includes atrazine, were introduced in the 1950s; they have the current distinction of being the herbicide family of greatest concern regarding groundwater contamination. Atrazine does not break down readily (within a few weeks) after being applied to soils of above neutral pH. Under alkaline soil conditions, atrazine may be carried into the soil profile as far as the water table by soil water following rainfall causing the aforementioned contamination. Atrazine is thus said to have "carryover", a generally undesirable property for herbicides.

Glyphosate (Roundup) was introduced in 1974 for nonselective weed control. Following the development of glyphosate-resistant crop plants, it is now used very extensively for selective weed control in growing crops. The pairing of the herbicide with the resistant seed contributed to the consolidation of the seed and chemistry industry in the late 1990s.

Many modern chemical herbicides for agriculture are specifically formulated to decompose within a short period after application. This is desirable, as it allows crops which may be affected by the herbicide to be grown on the land in future seasons. However, herbicides with low residual activity (i.e., that decompose quickly) often do not provide season-long weed control.

Health and environmental effects

Herbicides have widely variable toxicity. In addition to acute toxicity from high exposure levels, there is concern of possible carcinogenicity,[5] as well as other long-term problems, such as contributing to Parkinson's disease.

Some herbicides cause a range of health effects ranging from skin rashes to death. The pathway of attack can arise from intentional or unintentional direct consumption, improper application resulting in the herbicide coming into direct contact with people or wildlife, inhalation of aerial sprays, or food consumption prior to the labeled preharvest interval. Under some conditions, certain herbicides can be transported via leaching or surface runoff to contaminate groundwater or distant surface water sources. Generally, the conditions that promote herbicide transport include intense storm events (particularly shortly after application) and soils with limited capacity to adsorb or retain the herbicides. Herbicide properties that increase likelihood of transport include persistence (resistance to degradation) and high water solubility.[6]

Phenoxy herbicides are often contaminated with dioxins such as TCDD; research has suggested such contamination results in a small rise in cancer risk after exposure to these herbicides.[7] Triazine exposure has been implicated in a likely relationship to increased risk of breast cancer, although a causal relationship remains unclear.[8]

Herbicide manufacturers have at times made false or misleading claims about the safety of their products. Chemical manufacturer Monsanto Company agreed to change its advertising after pressure from New York attorney general Dennis Vacco; Vacco complained about misleading claims that its spray-on glyphosate-based herbicides, including Roundup, were safer than table salt and "practically non-toxic" to mammals, birds, and fish.[9] Roundup is toxic and has resulted in death after being ingested in quantities ranging from 85 to 200 ml, although it has also been ingested in quantities as large as 500 ml with only mild or moderate symptoms.[10] The manufacturer of Tordon 101 (Dow AgroSciences, owned by the Dow Chemical Company) has claimed Tordon 101 has no effects on animals and insects,[11] in spite of evidence of strong carcinogenic activity of the active ingredient[12] Picloram in studies on rats.[13]

The risk of Parkinson's disease has been shown to increase with occupational exposure to herbicides and pesticides.[14] The herbicide paraquat is suspected to be one such factor.[15]

All commercially sold, organic and nonorganic herbicides must be extensively tested prior to approval for sale and labeling by the Environmental Protection Agency. However, because of the large number of herbicides in use, concern regarding health effects is significant. In addition to health effects caused by herbicides themselves, commercial herbicide mixtures often contain other chemicals, including inactive ingredients, which have negative impacts on human health. For example, Roundup contains adjuvants which, even in low concentrations, were found to kill human embryonic, placental, and umbilical cells in vitro.[16] One study also found Roundup caused genetic damage, but the damage was not caused by the active ingredient.[17]

Ecological effects

Commercial herbicide use generally has negative impacts on bird populations, although the impacts are highly variable and often require field studies to predict accurately. Laboratory studies have at times overestimated negative impacts on birds due to toxicity, predicting serious problems that were not observed in the field.[18] Most observed effects are due not to toxicity, but to habitat changes and the decreases in abundance of species on which birds rely for food or shelter. Herbicide use in silviculture, used to favor certain types of growth following clearcutting, can cause significant drops in bird populations. Even when herbicides which have low toxicity to birds are used, they decrease the abundance of many types of vegetation on which the birds rely.[19] Herbicide use in agriculture in Britain has been linked to a decline in seed-eating bird species which rely on the weeds killed by the herbicides.[20] Heavy use of herbicides in neotropical agricultural areas has been one of many factors implicated in limiting the usefulness of such agricultural land for wintering migratory birds.[21]

Frog populations may be affected negatively by the use of herbicides as well. While some studies have shown that atrazine may be a teratogen, causing demasculinization in male frogs,[22] the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its independent Scientific Advisory Panel (SAP) examined all available studies on this topic and concluded that "atrazine does not adversely affect amphibian gonadal development based on a review of laboratory and field studies."[23]

Scientific uncertainty

The health and environmental effects of many herbicides is unknown, and even the scientific community often disagrees on the risk. For example, a 1995 panel of 13 scientists reviewing studies on the carcinogenicity of 2,4-D had divided opinions on the likelihood 2,4-D causes cancer in humans.[24] As of 1992[update], studies on phenoxy herbicides were too few to accurately assess the risk of many types of cancer from these herbicides, even though evidence was stronger that exposure to these herbicides is associated with increased risk of soft tissue sarcoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[5] Furthermore, there is some suggestion that herbicides[which?] can play a role in sex reversal of certain organisms that experience temperature-dependent sex determination, which could theoretically alter sex ratios.[25]

Resistance

Scientists generally agree selection pressure applied to weed populations for a long enough period of time eventually leads to resistance. Plants have developed resistance to atrazine and to ALS-inhibitors, and more recently, to glyphosate herbicides. Marestail is one weed that has developed glyphosate resistance.[26]

Glyphophate-resistant weeds are present in the vast majority of soybean, cotton and corn farms in some U.S. states. Weeds that can resist multiple other herbicides are spreading. Few new herbicides are near commercialization, and none with a molecular mode of action for which there is no resistance. Because most herbicides could not kill all weeds, farmers rotated crops and herbicides to stop resistant weeds. During its initial years, glyphosphate was not subject to resistance and allowed farmers to reduce the use of rotation.[27]

A family of weeds that includes waterhemp (Amaranthus rudis) is the largest concern. A 2008-9 survey of 144 populations of waterhemp in 41 Missouri counties revealed glyphosate resistance in 69%. Weeds from some 500 sites throughout Iowa in 2011 and 2012 revealed glyphosate resistance in approximately 64% of waterhemp samples. The use of other killers to target "residual" weeds has become common, and may be sufficient to have stopped the spread of resistance From 2005 through 2010 researchers discovered 13 different weed species that had developed resistance to glyphosate. But since then only two more have been discovered. Weeds resistant to multiple herbicides with completely different biological action modes are on the rise. In Missouri, 43% of samples were resistant to two different herbicides; 6% resisted three; and 0.5% resisted four. In Iowa 89% of waterhemp samples resist two or more herbicides, 25% resist three, and 10% resist five.[27]

For southern cotton, herbicide costs has climbed from between $50 and $75 per hectare a few years ago to about $370 per hectare in 2013. Resistance is contributing to a massive shift away from growing cotton; over the past few years, the area planted with cotton has declined by 70% in Arkansas and by 60% in TennesseeResistance is contributing to a massive shift away from growing cotton; over the past few years, the area planted with cotton has declined by 70% in Arkansas and by 60% in Tennessee. For soybeans in Illinois, costs have risen from about $25 to $160 per hectare.[27]

Dow, Bayer CropScience, Syngenta and Monsanto are all developing seed varieties resistant to herbicides other than glyphosate, which will make it easier for farmers to use alternative weed killers. Even though weeds have already evolved some resistance to those herbicides, Powles says the new seed-and-herbicide combos should work well if used with proper rotation.[27]

Farming practices

Herbicide resistance became a critical problem after many Australian sheep farmers switched to exclusively growing wheat in their pastures in the 1970s. In wheat fields, introduced varieties of ryegrass, while good for grazing sheep, are intense competitors with wheat. Ryegrasses produce so many seeds that, if left unchecked, they can completely choke a field. Herbicides provided excellent control, while reducing soil disrupting because of less need to plough. Within little more than a decade, ryegrass and other weeds began to develop resistance. Australian farmers evolved again and began diversifying their techniques.[28]

In 1983, patches of ryegrass had become immune to Hoegrass, a family of herbicides that inhibit an enzyme called acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase.[28]

Ryegrass populations were large, and had substantial genetic diversity, because farmers had planted many varieties. Ryegrass is cross-pollinated by wind, so genes shuffle frequently. Farmers sprayed inexpensive Hoegrass year after year, creating selection pressure, but were diluting the herbicide in order to save money, increasing plants survival. Hoegrass was mostly replaced by a group of herbicides that blockacetolactate synthase, again helped by poor application practices. Ryegrass evolved a kind of "cross-resistance" that allowed it to rapidly break down a variety of herbicides. Australian farmers lost four classes of herbicides in only a few years. As of 2013 only two herbicide classes, called Photosystem II and long-chain fatty acid inhibitors, had become the last hope.[28]

Classification

Herbicides can be grouped by activity, use, chemical family, mode of action, or type of vegetation controlled.

By activity:

- Contact herbicides destroy only the plant tissue in contact with the chemical. Generally, these are the fastest acting herbicides. They are less effective on perennial plants, which are able to regrow from rhizomes, roots or tubers.

- Systemic herbicides are translocated through the plant, either from foliar application down to the roots, or from soil application up to the leaves. They are capable of controlling perennial plants and may be slower-acting, but ultimately more effective than contact herbicides.

By use:

- Soil-applied herbicides are applied to the soil and are taken up by the roots and/or hypocotyl of the target plant. The three main types are:

- Preplant incorporated herbicides are soil applied prior to planting and mechanically incorporated into the soil. The objective for incorporation is to prevent dissipation through photodecomposition and/or volatility.

- Pre-emergent herbicides are applied to the soil before the crop emerges and prevent germination or early growth of weed seeds.

- Postemergent herbicides are applied after the crop has emerged.

Their classification by mechanism of action (MOA) indicates the first enzyme, protein, or biochemical step affected in the plant following application. The main mechanisms of action are:

- ACCase inhibitors compounds kill grasses. Acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCase) is part of the first step of lipid synthesis. Thus, ACCase inhibitors affect cell membrane production in the meristems of the grass plant. The ACCases of grasses are sensitive to these herbicides, whereas the ACCases of dicot plants are not.

- ALS inhibitors: the acetolactate synthase (ALS) enzyme (also known as acetohydroxyacid synthase, or AHAS) is the first step in the synthesis of the branched-chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine). These herbicides slowly starve affected plants of these amino acids, which eventually leads to inhibition of DNA synthesis. They affect grasses and dicots alike. The ALS inhibitor family includes sulfonylureas, imidazolinones, triazolopyrimidines, pyrimidinyl oxybenzoates, and sulfonylamino carbonyl triazolinones. The ALS biological pathway exists only in plants and not animals, thus making the ALS-inhibitors among the safest herbicides.[citation needed]

- EPSPS inhibitors: The enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase enzyme EPSPS is used in the synthesis of the amino acids tryptophan, phenylalanine and tyrosine. They affect grasses and dicots alike. Glyphosate (Roundup) is a systemic EPSPS inhibitor inactivated by soil contact.

- Synthetic auxins inaugurated the era of organic herbicides. They were discovered in the 1940s after a long study of the plant growth regulator auxin. Synthetic auxins mimic this plant hormone. They have several points of action on the cell membrane, and are effective in the control of dicot plants. 2,4-D is a synthetic auxin herbicide.

- Photosystem II inhibitors reduce electron flow from water to NADPH2+ at the photochemical step in photosynthesis. They bind to the Qb site on the D1 protein, and prevent quinone from binding to this site. Therefore, this group of compounds causes electrons to accumulate on chlorophyll molecules. As a consequence, oxidation reactions in excess of those normally tolerated by the cell occur, and the plant dies. The triazine herbicides (including atrazine) and urea derivatives (diuron) are photosystem II inhibitors.[29]

- Photosystem I inhibitors steal electrons from the normal pathway through FeS – Fdx – NADP leading to direct discharge of electrons on oxygen. As a result, reactive oxygen species are produced and oxidation reactions in excess of those normally tolerated by the cell occur, leading to plant death.

Bipyridinium herbicides (such as diquat and paraquat) hit the "Fe-S – Fdx step" while diphenyl ether herbicide (such as nitrofen, nitrofluorfen, and acifluorfen) hit the "Fdx – NADP step".[clarification needed][29]

Organic herbicides

Recently, the term "organic" has come to imply products used in organic farming. Under this definition, an organic herbicide is one that can be used in a farming enterprise that has been classified as organic. Commercially sold organic herbicides are expensive and may not be affordable for commercial farming.[citation needed] Depending on the application, they may be less effective than synthetic herbicides and are generally used along with cultural and mechanical weed control practices.

Homemade organic herbicides include:

- Corn gluten meal (CGM) is a natural pre-emergence weed control used in turfgrass, which reduces germination of many broadleaf and grass weeds.[30]

- Spices are now effectively used in herbicides.[citation needed]

- Vinegar[31] is effective for 5–20% solutions of acetic acid, with higher concentrations most effective, but it mainly destroys surface growth, so respraying to treat regrowth is needed. Resistant plants generally succumb when weakened by respraying.

- Steam has been applied commercially, but is now considered uneconomical and inadequate.[32][33][34] It kills surface growth but not underground growth and so respraying to treat regrowth of perennials is needed.

- Flame is considered more effective than steam, but suffers from the same difficulties.[35]

- D-limonene (citrus oil) is a natural degreasing agent that strips the waxy skin or cuticle from weeds, causing dehydration and ultimately death.[citation needed]

- Saltwater or salt applied in appropriate strengths to the rootzone will kill most plants.[citation needed]

- Monocerin produced by certain fungi will kill certain weeds such as Johnson grass.[citation needed]

Application

Most herbicides are applied as water-based sprays using ground equipment. Ground equipment varies in design, but large areas can be sprayed using self-propelled sprayers equipped with long booms, of 60 to 80 feet (18 to 24 m) with flat-fan nozzles spaced about every 20 inches (510 mm). Towed, handheld, and even horse-drawn sprayers are also used.

Synthetic organic herbicides can generally be applied aerially using helicopters or airplanes, and can be applied through irrigation systems (chemigation).

A new method of herbicide application involves ridding the soil of its active weed seed bank rather than just killing the weed. Researchers at the Agricultural Research Service have found the application of herbicides to fields late in the weeds' growing season greatly reduces their seed production, and therefore fewer weeds will return the following season. Because most weeds are annual grasses, their seeds will only survive in soil for a year or two, so this method will be able to “weed out” the weed with only a few years of herbicide application.[36]

Weed-wiping may also be used, where a wick wetted with herbicide is suspended from a boom and dragged or rolled across the tops of the taller weed plants. This allows treatment of taller grassland weeds by direct contact without affecting related but desirable plants in the grassland sward beneath.

Misapplication

Herbicide volatilisation or drift may result in herbicide affecting neighboring fields or plants, particularly in windy conditions. Sometimes, the wrong field or plants may be sprayed due to error.

Terminology

- Control is the destruction of unwanted weeds, or the damage of them to the point where they are no longer competitive with the crop.

- Suppression is incomplete control still providing some economic benefit, such as reduced competition with the crop.

- Crop safety, for selective herbicides, is the relative absence of damage or stress to the crop. Most selective herbicides cause some visible stress to crop plants.

In current use

- 2,4-D is a broadleaf herbicide in the phenoxy group used in turf and no-till field crop production. Now, it is mainly used in a blend with other herbicides to allow lower rates of herbicides to be used; it is the most widely used herbicide in the world, and third most commonly used in the United States. It is an example of synthetic auxin (plant hormone).[citation needed]

- Aminopyralid is a broadleaf herbicide in the pyridine group, used to control weeds on grassland, such as docks, thistles and nettles. It is notorious for its ability to persist in compost.[citation needed]

- Atrazine, a triazine herbicide, is used in corn and sorghum for control of broadleaf weeds and grasses. Still used because of its low cost and because it works well on a broad spectrum of weeds common in the US corn belt, atrazine is commonly used with other herbicides to reduce the overall rate of atrazine and to lower the potential for groundwater contamination; it is a photosystem II inhibitor.[citation needed]

- Clopyralid is a broadleaf herbicide in the pyridine group, used mainly in turf, rangeland, and for control of noxious thistles. Notorious for its ability to persist in compost, it is another example of synthetic auxin.[citation needed]

- Dicamba, a postemergent broadleaf herbicide with some soil activity, is used on turf and field corn. It is another example of a synthetic auxin.

- Glufosinate ammonium, a broad-spectrum contact herbicide, is used to control weeds after the crop emerges or for total vegetation control on land not used for cultivation.

- Fluazifop (Fuselade Forte), a post emergence, foliar absorbed, translocated grass-selective herbicide with little residual action. It is used on a very wide range of broad leaved crops for control of annual and perennial grasses.[37]

- Fluroxypyr, a systemic, selective herbicide, is used for the control of broad-leaved weeds in small grain cereals, maize, pastures, rangeland and turf. It is a synthetic auxin. In cereal growing, fluroxypyr's key importance is control of cleavers, Galium aparine. Other key broadleaf weeds are also controlled.

- Glyphosate, a systemic nonselective herbicide, is used in no-till burndown and for weed control in crops genetically modified to resist its effects. It is an example of an EPSPs inhibitor.

- Imazapyr a nonselective herbicide, is used for the control of a broad range of weeds, including terrestrial annual and perennial grasses and broadleaf herbs, woody species, and riparian and emergent aquatic species.

- Imazapic, a selective herbicide for both the pre- and postemergent control of some annual and perennial grasses and some broadleaf weeds, kills plants by inhibiting the production of branched chain amino acids (valine, leucine, and isoleucine), which are necessary for protein synthesis and cell growth.

- Imazamox, an imidazolinone manufactured by BASF for postemergence application that is an acetolactate synthase (ALS) inhibitor. Sold under trade names Raptor, Beyond, and Clearcast.[38]

- Linuron is a nonselective herbicide used in the control of grasses and broadleaf weeds. It works by inhibiting photosynthesis.

- Metolachlor is a pre-emergent herbicide widely used for control of annual grasses in corn and sorghum; it has displaced some of the atrazine in these uses.

- Paraquat is a nonselective contact herbicide used for no-till burndown and in aerial destruction of marijuana and coca plantings. It is more acutely toxic to people than any other herbicide in widespread commercial use.

- Pendimethalin, a pre-emergent herbicide, is widely used to control annual grasses and some broad-leaf weeds in a wide range of crops, including corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, many tree and vine crops, and many turfgrass species.

- Picloram, a pyridine herbicide, mainly is used to control unwanted trees in pastures and edges of fields. It is another synthetic auxin.

- Sodium chlorate, a nonselective herbicide, is considered phytotoxic to all green plant parts. It can also kill through root absorption.

- Triclopyr, a systemic, foliar herbicide in the pyridine group, is used to control broadleaf weeds while leaving grasses and conifers unaffected.

Historical interest: 2,4,5-T

- 2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) was a widely used broadleaf herbicide until being phased out starting in the late 1970s. While 2,4,5-T itself is of only moderate toxicity, the manufacturing process for 2,4,5-T contaminates this chemical with trace amounts of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). TCDD is extremely toxic to humans. With proper temperature control during production of 2,4,5-T, TCDD levels can be held to about .005 ppm. Before the TCDD risk was well understood, early production facilities lacked proper temperature controls. Individual batches tested later were found to have as much as 60 ppm of TCDD.

- 2,4,5-T was withdrawn from use in the USA in 1983, at a time of heightened public sensitivity about chemical hazards in the environment. Public concern about dioxins was high, and production and use of other (non-herbicide) chemicals potentially containing TCDD contamination was also withdrawn. These included pentachlorophenol (a wood preservative) and PCBs (mainly used as stabilizing agents in transformer oil). Some feel [who?] that the 2,4,5-T withdrawal was not based on sound science. 2,4,5-T has since largely been replaced by dicamba and triclopyr.

- Agent Orange was an herbicide blend used by the British military during the Malayan Emergency and the U.S. military during the Vietnam War between January 1965 and April 1970 as a defoliant. It was a 50/50 mixture of the n-butyl esters of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. Because of TCDD contamination in the 2,4,5-T component,[citation needed] it has been blamed for serious illnesses in many people who were exposed to it. However, research on populations exposed to its dioxin contaminant have been inconsistent and inconclusive.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b Kellogg RL, Nehring R, Grube A, Goss DW, and Plotkin S (February 2000). "Environmental indicators of pesticide leaching and runoff from farm fields". United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andrew H. Cobb, John P. H. Reade (2011). "7.1". Herbicides and Plant Physiology. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Robert L Zimdahl (2007). A History of Weed Science in the United States. Elsevier.

- ^ Quastel, J. H. (1950). "Agricultural Control Chemicals". Advances in Chemistry. 1: 244. doi:10.1021/ba-1950-0001.ch045. ISBN 0-8412-2442-0.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Howard I. Morrison, Kathryn Wilkins, Robert Semenciw, Yang Mao, Don Wigle (1992). "Herbicides and Cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 84 (24): 1866–1874. doi:10.1093/jnci/84.24.1866. PMID 1460670.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ PL Havens, GK Sims, S Erhardt-Zabik. 1995. Fate of herbicides in the environment. Handbook of weed management systems. M. Dekker, 245-278

- ^ Kogevinas, M; Becher, H; Benn, T; Bertazzi, PA; Boffetta, P; Bueno-De-Mesquita, HB; Coggon, D; Colin, D; Flesch-Janys, D (1997). "Cancer mortality in workers exposed to phenoxy herbicides, chlorophenols, and dioxins. An expanded and updated international cohort study". American journal of epidemiology. 145 (12): 1061–75. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009069. PMID 9199536.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Kettles, MK; Browning, SR; Prince, TS; Horstman, SW (1997). "Triazine herbicide exposure and breast cancer incidence: An ecologic study of Kentucky counties". Environmental health perspectives. 105 (11): 1222–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.971051222. PMC 1470339. PMID 9370519.

- ^ "Monsanto Pulls Roundup Advertising in New York". Wichita Eagle. Nov 27, 1996.

- ^ Talbot, AR; Shiaw, MH; Huang, JS; Yang, SF; Goo, TS; Wang, SH; Chen, CL; Sanford, TR (1991). "Acute poisoning with a glyphosate-surfactant herbicide ('Roundup'): A review of 93 cases". Human & experimental toxicology. 10 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1177/096032719101000101. PMID 1673618.

- ^ "Complaints halt herbicide spraying in Eastern Shore". CBC News. June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Tordon 101: picloram/2,4-D", Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food & Rural Affairs

- ^ Reuber, MD (1981). "Carcinogenicity of Picloram". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. 7 (2): 207–222. doi:10.1080/15287398109529973. PMID 7014921.

- ^ Gorell, JM; Johnson, CC; Rybicki, BA; Peterson, EL; Richardson, RJ (1998). "The risk of Parkinson's disease with exposure to pesticides, farming, well water, and rural living". Neurology. 50 (5): 1346–50. doi:10.1212/WNL.50.5.1346. PMID 9595985.

- ^ Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Remião, F.; Carmo, H.; Duarte, J.A.; Navarro, A. Sánchez; Bastos, M.L.; Carvalho, F. (2006). "Paraquat exposure as an etiological factor of Parkinson's disease". NeuroToxicology. 27 (6): 1110–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2006.05.012. PMID 16815551.

- ^ Benachour, Nora (December 23, 2008). "Glyphosate Formulations Induce Apoptosis and Necrosis in Human Umbilical, Embryonic, and Placental Cells". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 22 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1021/tx800218n. PMID 19105591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Peluso, M; Munnia, A; Bolognesi, C; Parodi, S (1998). "32P-postlabeling detection of DNA adducts in mice treated with the herbicide Roundup". Environmental and molecular mutagenesis. 31 (1): 55–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1998)31:1<55::AID-EM8>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 9464316.

- ^ Blus, Lawrence J.; Henny, Charles J. (1997). "Field Studies on Pesticides and Birds: Unexpected and Unique Relations". Ecological Applications. 7 (4): 1125. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1997)007[1125:FSOPAB]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ MacKinnon, D. S. and Freedman, B. (1993). "Effects of Silvicultural Use of the Herbicide Glyphosate on Breeding Birds of Regenerating Clearcuts in Nova Scotia, Canada". Journal of Applied Ecology. 30 (3): 395–406. doi:10.2307/2404181. JSTOR 2404181.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newton, Ian (2004). "The recent declines of farmland bird populations in Britain: An appraisal of causal factors and conservation actions". Ibis. 146 (4): 579. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00375.x.

- ^ Robbins, C.S.; Dowell, B.A.; Dawson, D.K.; Colon, J.A.; Estrada, R.; Sutton, A.; Sutton, R.; Weyer, D. (1992). "Comparison of neotropical migrant landbird populations wintering in tropical forest, isolated forest fragments, and agricultural habitats". Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical Migrant Landbirds. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London. pp. 207–220. ISBN 156098113X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayes, Tyrone B., et al. "Hermaphroditic, demasculinized frogs after exposure to the herbicide atrazine at low ecologically relevant doses." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99.8 (2002): 5476-5480.

- ^ Environmental Protection Agency: Atrazine Updates. Current as of January 2013, URL accessed August 24, 2013.

- ^ Ibrahim MA, Bond GG, Burke TA, Cole P, Dost FN, Enterline PE, Gough M, Greenberg RS, Halperin WE, McConnell E; et al. (1991). "Weight of the evidence on the human carcinogenicity of 2,4-D". Environ Health Perspect. 96: 213–222. PMC 1568222. PMID 1820267.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gilbert, Scott F (2010). Developmental Biology (9th ed.). Sinauer Associates. p. [page needed]. ISBN 978-0-87893-384-6.

- ^ Marking, Syl (January 1, 2002) "Marestail Jumps Glyphosate Fence", Corn and Soybean Digest.

- ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.341.6152.1329, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.341.6152.1329instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.341.6147.734, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.341.6147.734instead. - ^ a b Stryer, Lubert (1995). Biochemistry, 4th Edition. W.H. Freeman and Company. p. 670. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ McDade, Melissa C.; Christians, Nick E. (2009). "Corn gluten meal—a natural preemergence herbicide: Effect on vegetable seedling survival and weed cover". American Journal of Alternative Agriculture. 15 (4): 189. doi:10.1017/S0889189300008778.

- ^ Spray Weeds With Vinegar?. Ars.usda.gov. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Weed Management in Landscapes. Ipm.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ Lanini, W. Thomas Organic Weed Management in Vineyards. University of California, Davis

- ^ Kolberg, Robert L., and Lori J. Wiles (2002). "Effect of Steam Application on Cropland Weeds1". Weed Technology. 16: 43. doi:10.1614/0890-037X(2002)016[0043:EOSAOC]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Flame weeding for vegetable crops. Attra.ncat.org (2011-10-12). Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ "A New Way to Use Herbicides: To Sterilize, Not Kill Weeds". USDA Agricultural Research Service. May 5, 2010.

- ^ Fluazifop. Herbiguide.com.au. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

- ^ IMAZAMOX | Pacific Northwest Weed Management Handbook. Pnwhandbooks.org. Retrieved on 2013-03-05.

Further reading

- A Brief History of On-track Weed Control in the N.S.W. SRA during the Steam Era Longworth, Jim Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, April, 1996 pp99–116

External links

- General Information

- National Pesticide Information Center, Information about pesticide-related topics

- National Agricultural Statistics Service

- Regulatory policy