Corruption in Venezuela

Corruption in Venezuela is high by world standards. In the case of Venezuela, the discovery of oil in the early twentieth century has worsened political corruption.[1]

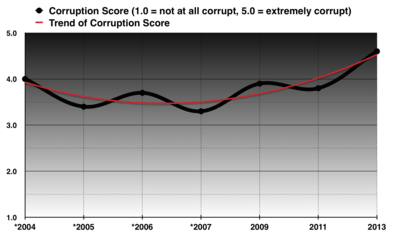

Corruption is difficult to measure reliably, but one well-known measure is the Corruption Perceptions Index, produced annually by the Berlin-based NGO, Transparency International (TNI). In recent years, corruption has worsened; it was 158th out of 180 countries in 2008, and 165th out of 176 (tied with Burundi, Chad, and Haiti)[2]). Most Venezuelans believe the government's effort against corruption is ineffective, that corruption has increased, and that government institutions such as the judicial system, parliament, legislature and police are the most corrupt.[3] According to TNI, Venezuela is currently among the top 20 most corrupt countries in the world ranking 17 with its judicial system has been deemed the most corrupt in the world.[4]

In 2014, 75% of Venezuelans believed that corruption was widespread throughout the Venezuelan government.[5] This popular discontent with corruption in the Venezuelan government was one of the primary causes of the 2014 Venezuelan protests.[6]

History

During the Venezuelan War of Independence in 1813, Simón Bolívar made a decree that any corruption was punishable by death. Inuring his presidency in the 1820's, he made two more decrees stating corruption was “the violation of the public interest” and reinforced his edict that it was punishable by death. Since then, the past 180 years of Venezuela have been defined by the "persistent and intense presence of corruption".[7] In 1991, author Ruth Capriles wrote The history of corruption in Venezuela is the history of our democracy depicting the many instances in the country.[8] In 1997, Pro Calidad de Vida, a Venezuelan NGO claimed that some $100 billion from oil revenue has been misused during the last 25 years.[7]

Joaquín Crespo

Joaquín Crespo was renowned for establishing the "ring of iron" by making connections with officials before the end of his first term in 1886, and placing his friends on congressional seats to help guarantee his reelection.[9]

Antonio Guzmán Blanco

In 1888, Antonio Guzmán Blanco led a fairly steady Venezuelan government that was allegedly ripe with corruption.[10] Guzmán Blanco reportedly stole money from the treasury, abused his power, and, after a disagreement with a bishop, expelled any clergy who disagreed with him and seized property belonging to the Catholic Church.[11][12]

Cipriano Castro

After a successful coup in 1899, the dictatorship of Cipriano Castro was one of the most corrupt periods in Venezuela's history. Once in charge, Castro began plundering the treasury and modifying the constitution to convenience his administration. He had political opponents murdered or exiled, lived extravagantly and broke down diplomacy with foreign countries. He provoked numerous foreign actions, including the blockades and bombardments by British, German, and Italian naval vessels seeking to enforce the claims of their citizens against Castro's government.[13]

Juan Vicente Gómez

From 1909 to 1935, the dictator Juan Vincente Gomez held power, with his acts of corruption only committed with "immediate collaborators".[7] By the time he died, he was by far the richest man in the country. He did little for public education and held basic democratic principles in disdain. His allegedly ruthless crushing of opponents through his secret police earned him the reputation of a tyrant. He was also accused by opponents of trying to turn the country into a personal fiefdom.

Marcos Pérez Jiménez

Marcos Pérez Jiménez seized power through a coup in 1952 and declared himself provisional president until being formally elected in 1953. The government's National Security (Seguridad Nacional, secret police) was extremely repressive against critics of the regime and ruthlessly hunted down and imprisoned those who opposed the dictatorship. In 1957 during the time of reelection, voters had only the choice between voting "yes" or "no" to another term for Jiménez. Pérez Jiménez won by a large margin, though by numerous accounts the count was blatantly rigged.

Raúl Leoni

President Raúl Leoni spent $10 million of public funds to pave a road to his house, to build guest houses near his home, and to add air-conditioning to the local airport.[8]

Jaime Lusinchi

During the presidency from 1984-1989 of Jaime Lusinchi, US$36 billion were misused by the foreign exchange program RECADI.[7]

Carlos Andrés Pérez

On 20 March 1993, Attorney General Ramón Escovar Salom introduced action against President Carlos Andrés Pérez for the embezzlement of 250 million bolivars belonging to a presidential discretionary fund, or partida secreta. The issue had originally been brought to public scrutiny in November 1992 by journalist José Vicente Rangel. Pérez and his supporters claim the money was used to support the electoral process in Nicaragua. On 20 May 1993, the Supreme Court considered the accusation valid, and the following day the Senate voted to strip Pérez of his immunity. Pérez refused to resign, but after the maximum 90 days temporary leave available to the President under Article 188 of the 1961 constitution, the National Congress removed Pérez from office permanently on 31 August.[14]

Bolivarian Revolution

The government in place following the Bolivarian Revolution has been frequently accused of corruption, abuse of the economy for personal gain, propaganda, buying the loyalty of the military, officials involved in drug trade, assisting terrorists, intimidation of the media, and human rights abuses of its citizens.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24] In Gallup Poll's 2006 Corruption Index, Venezuela ranks 31st out of 101 countries according to how widespread the population perceive corruption as being in the government and in business. The index lists Venezuela as the second least corrupt nation in Latin America, behind Chile.[25] In August 2006, following assaults on a squatter and a National Assembly member, El Universal says that Chávez called on the latest Minister, Jesse Chacón to quit if he could not do the job, demanding more effort in the fight against corruption, and affirming the need to clean up and reform the local police forces. He questioned the impunity that exists in the country, and challenged authorities, like Chacón, to resign if they could not make progress against crime. He also called for greater protection of squatters settling on landed estates.[26] Some criticism came from Chávez's supporters. Chávez's own political party, Fifth Republic Movement (MVR), had been criticized as being riddled with the same cronyism, political patronage, and corruption that Chávez alleged were characteristic of the old "Fourth Republic" political parties. Venezuela's trade unionists and indigenous communities have participated in peaceful demonstrations intended to impel the government to facilitate labor and land reforms. These communities, while largely expressing their sympathy and support for Chávez, criticize what they see as Chávez's slow progress in protecting their interests against managers and mining concerns, respectively.[27][28][29]

In 2014, the World Justice Project ranked Venezuela's government in 99th place worldwide and gave it the worst ranking of countries in Latin America according to the Rule of Law Index 2014. The report says, "Venezuela is the country with the poorest performance of all countries analysed, showing decreasing trends in the performance of many areas in relation to last year. The country ranks last in the surrender of accounts by the government due to an increasing concentration of executive power and a weakened checks and balances" and that, "administrative bodies suffer inefficiencies and lack of transparency in its activity, and the judicial system, although relatively accessible, lost positions due to increasing political interference. Another area of concern is the increase in crime and violence, and violations of fundamental rights; particularly the right to freedom of opinion and expression".[23]

Hugo Chávez

In December 1998, Hugo Chavez declared three goals for the new government; "convening a constituent assembly to write a new constitution, eliminating government corruption, and fighting against social exclusion and poverty". However, during Hugo Chávez's time in power, corruption has become widespread throughout the government due to impunity towards members of the government, bribes and the lack of transparency.[7] In 2004, Hugo Chávez and his allies took over the Supreme Court, filling it with supporters of Chávez and made new measures so the government could dismiss justices from the court.[30] According to the Cato Institute, the National Electoral Council of Venezuela was under control of Chávez where he tried to "push a constitutional reform that would have allowed him unlimited opportunities for reelection".[20]

Public funds

$22.5 billion of public funds have been transferred from Venezuela to foreign accounts with half of that money being unaccounted for by anyone.[20] José Guerra, a former Central Bank executive, claims that most of that money has been used to buy political allies in countries such as Cuba and Bolivia.[20] Chávez reportedly made promises and carried out most payments of nearly $70 billion USD to foreign leaders without the consultation of the people of Venezuela and without normal legal procedures.[20]

Maletinazo scandal

In August 2007, es, a self-identified member of the entourage of Hugo Chávez, who was about to visit Argentina, arrived in Argentina on a private flight paid for by Argentine and Venezuelan state officials. Wilson was carrying $800,000 USD in cash, which the police seized on arrival. A few days later Wilson, a Venezuelan-American and a close friend of Chávez's, was a guest at a signing ceremony involving Cristina Kirchner and Chávez at the Casa Rosada. He was later arrested on money laundering and contraband charges. It was alleged that the cash was to have been delivered to the Kirchner's as a clandestine contribution to Cristina's campaign chest from President Chávez. Fernández, as a fellow leftist, was a political ally of Chávez. This was seen as a similar move that Chávez allegedly used to give payments to leftist candidates in presidential races for Bolivia and Mexico in order to back his anti-US allies.[31] The incident led to a scandal and what Bloomberg News called “an international imbroglio,” with the U.S. accusing five men of being secret Chávez agents whose mission was to cover up the attempt to deliver the cash.[32][33]

Aiding FARC

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), "Chavez's government funded FARC's office in Caracas and gave it access to Venezuela's intelligence services" and said that during the 2002 coup attempt that, "FARC also responded to requests from (Venezuela's intelligence service) to provide training in urban terrorism involving targeted killings and the use of explosives." The IISS continued saying that "the archive offers tantalizing but ultimately unproven suggestions that FARC may have undertaken assassinations of Chavez's political opponents on behalf of the Venezuelan state." Venezuelan diplomats denounced the IISS' findings saying that the had "basic inaccuracies".[34]

Chavez's government allegedly gave money, weapons and support to the FARC, a rebel guerilla movement in Colombia known for extensive kidnappings and control of the drug trade. The suspicion of Venezuelan support was repeatedly confirmed. In 2005, captured laptops belonging to FARC leaders showed Chavez's involvement and support. The FARC rebels sought Venezuelan assistance in acquiring surface-to-air missiles. These files were confirmed by Interpol as being authentic.[35] Files found in Equador showed FARC spent $400,000 to support the presidential campaign of Rafael Correa, an ally of Chavez. The documents allege that Chavez met personally with rebel leaders.[36]

In 2007, authorities in Colombia claimed that through laptops they had seized on a raid against Raul Reyes, they found in documents that Hugo Chávez offered payments of as much as $300 million to the FARC "among other financial and political ties that date back years" along with other documents showing "high-level meetings have been held between rebels and Ecuadorean officials" and some documents claiming that FARC had "bought and sold uranium".[31][37]

Diosdado Cabello

President of the Venezuelan National Assembly Diosdado Cabello has been accused of bribery, organizing pro-govenrment paramilitary forces, and being one of the most corrupt officials in Venezuela. Information presented to the United States State Department by Stratfor that was revealed through Wikileaks said that Cabello was head of "one of the major centers of corruption in Venezuela."[38]

Derwick Associates bribes

In 2014, Cabello was charged by a court in Miami, Florida of accepting bribes from Derwick Associates including a $50 million dollar payment. These bribes were reportedly made so Derwick Associates could get public contracts from the Venezuelan government.[38]

Organizing colectivos

Cabello, along with Freddy Bernal and Eliezer Otaiza, have been accused of directing colectivos by organizing and paying them with money from the funds of Petróleos de Venezuela.[39]

Labor

In the World Report 2014 by Human Rights Watch, the organization stated that "[p]olitical discrimination against workers in state institutions remains a problem". Human Rights Watch explained that hundreds of public workers from the state oil company, the office in charge of customs and taxes, and state electrical companies, were all threatened of losing their jobs if they supported the opposition or did not show enough support for President Maduro. Minister of Housing, Ricardo Molina, also said that he would fire anyone who criticized Chavez, Maduro or the "revolution". The National Electoral Council (CNE), a government authority, is also in charge of union elections and is criticized by Human Rights Watch for "violating international standards that guarantee workers the right to elect their representatives in full freedom".[40]

Terrorist organizations and drug trade

Major government and military officials have been known for their involvement with crime. Members of the Venezuelan government were accused of providing financial aid to the Islamic militant group Hezbollah.[41]

Senior Venezuelan government officials have been known to associate with the narcotic terrorist organization FARC and "armed, abetted, and funded the FARC, even as it terrorized and kidnapped innocents".[42] There have been several incidents involving drugs being trafficked from Venezuela with supposed aid from corrupt officials. In September 2013, an incident involving men from the Venezuelan National Guard placing 31 suitcases containing 1.3 tons of cocaine on a Paris flight astonished French authorities.[17] According to former Venezuelan Supreme Court Justice Eladio Aponte, he was forced to acquit an army commander who had connections with a 2 metric ton shipment of cocaine. Aponte also claimed that Henry Rangel, former defense minister of Venezuela and General Clíver Alcalá Cordones were both involved with the drug trade in Venezuela.[17] Venezuelan officials have also been allegedly working with Mexican drug cartels.[17]

On 15 February 2014, a commander for the Venezuelan National Guard was stopped while driving to Valencia with his family and was arrested for having 554 kilos of cocaine in his possession.[43]

Judicial system

Venezuela's judicial system has been deemed the most corrupt in the world by Transparency International.[4] In 2004, Hugo Chávez and his allies took over of the Supreme Court, filling it with supporters and making new measures allowing the government to dismiss justices from the court.[30] In 2010, legislators from Chávez’s political party appointed 9 permanent judges and 32 stand-ins, which included several allies.[30] Judges may face reprisals if they rule against government interests.[30] According to a 2014 Gallup poll, 61% of Venezuelan's lack confidence in the judicial system.[5]

National Electoral Council

According to the Cato Institute, the National Electoral Council of Venezuela was under control of Chávez where he tried to "push a constitutional reform that would have allowed him unlimited opportunities for reelection".[20]

Police force

According to some sources Venezuela's corruption includes widespread corruption in the police force.[44] Many victims are afraid to report crimes to the police because many officers are involved with criminals and may bring even more harm to the victims.[45] Human Rights Watch claims that the "police commit one of every five crimes" and that thousands of people have been killed by police officers acting with impunity (only 3% of officers have been charged in cases against them).[30] The Metropolitan Police force in Caracas was so corrupt that it was disbanded and was even accused of assisting in many of the 17,000 kidnappings.[46] Medium says that the Venezuelan police are "seen as brutal and corrupt" and are "more likely to rob you than help".[47]

See also

General:

References

- ^ From 1917, "greater awareness of the country's oil potential had the pernicious effect of increasing the corruption and intrigue amongst Gomez's family and entourage, the consequences of which would be felt up to 1935 – B. S. McBeth (2002), Juan Vicente Gómez and the Oil Companies in Venezuela, 1908–1935, Cambridge University Press, p17.

- ^ "Factbox: Transparency International's global corruption index". Reuters. 5 December 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ "GLOBAL CORRUPTION BAROMETER 2010/11". Transparency International. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ a b "CORRUPTION BY COUNTRY / TERRITORY: VENEZUELA". Transparency International. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Venezuelans Saw Political Instability Before Protests". Gallup. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Venezuelans in US March Against Their Country's Violent, Corrupt Government". Christian Post. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Coronel, Gustavo. "Corruption, Mismanagement, and Abuse of Power in Hugo Chávez's Venezuela". Cato Institute.

- ^ a b Marx, Gary (22 September 1991). "Venezuela Corruption-from A To Z". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ McBeth, Brian S. (2001). Gunboats, corruption, and claims : foreign intervention in Venezuela, 1899-1908 (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0313313561.

- ^ Levin, Judith (2007). Hugo Chavez. New York: Chelsea House. p. 119. ISBN 978-0791092583.

- ^ Lewis, Paul H. (2006). Authoritarian regimes in Latin America : dictators, despots, and tyrants. Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 62. ISBN 978-0742537392.

- ^ Marshall, edited by Paul A. (2008). Religious freedom in the world. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 424. ISBN 978-0742562134.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ Lewis, Paul H. (2006). Authoritarian regimes in Latin America : dictators, despots, and tyrants. Lanham, Md. [u.a.]: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742537392.

- ^ Kada, Naoko (2003), "Impeachment as a punishment for corruption? The cases of Brazil and Venezuela", in Jody C. Baumgartner, Naoko Kada (eds, 2003), Checking executive power: presidential impeachment in comparative perspective, Greenwood Publishing Group

- ^ Marshall, edited by Paul A. (2008). Religious freedom in the world. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 423, 424. ISBN 978-0742562134.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "Treasury Targets Venezuelan Government Officials Supporting the FARC". Press Release. United States Department of Treasury. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d Meza, Alfredo (26 September 2013). "Corrupt military officials helping Venezuela drug trade flourish". El Pais. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Treasury Targets Hizballah in Venezuela". Press Release. United State Department of Treasury. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Romero, Simon (4 February 2011). "In Venezuela, an American Has the President's Ear". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Coronel, Gustavo. "The Corruption of Democracy in Venezuela". Cato Institute. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Venezuela's Drug-Running Generals May Be Who Finally Ousts Maduro". Vice News. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "World Report 2012: Venezuela". The Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Venezuela ocupa último lugar de naciones latinoamericanas analizadas". El Nacional. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Venezuela violates human rights, OAS commission reports". CNN. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ Steve Crabtree and Nicole Naurath Gallup Launches Worldwide Corruption Index Gallup Poll News Service Accessed 21 Dec 2006.

- ^ Diaz, Sara Carolina. Chávez exige acabar con latifundios. El Universal (7 August 2006).

- ^ Fuentes, F. (2005), "Challenges for Venezuela's Workers’ Movement". Green Left Weekly. Accessed 15 February 2006.

- ^ Márquez, H. (2005), [1] Inter Press Service. Accessed 2 February 2006.

- ^ Parma, A. Venezuela Analysis (2005a), "Pro-Chavez Union Leaders in Venezuela Urge Chavez to Do Better". Venezuela Analysis. Accessed 26 January 2006.

- ^ a b c d e "World Report 2012: Venezuela". Report. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ a b Padgett, Tim (3 September 2008). "Chávez and the Cash-Filled Suitcase". TIME. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ http://en.mercopress.com/2007/08/10/another-stashed-money-scandal-rocks-kirchner-s-administration

- ^ http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a73rBCz3iDho&refer=latin_america

- ^ Martinez, Michael (10 May 2011). "Study: Colombian rebels were willing to kill for Venezuela's Chavez". CNN. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Forero, Juan (16 May 2008). "FARC Computer Files Are Authentic, Interpol Probe Finds". Washington Post. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "FARC files 'show ties to Chavez'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Colombia: Chavez funding FARC rebels". USA Today. 4 March 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Demanda afirma que Diosdado Cabello recibió sobornos por $50 millones". El Nuevo Herald. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "NC COMMAND ATTACKS CRIMINAL TEAM: Diosdado Cabello-Freddy Bernal-Eliezer Otaiza". Ahora Vision. 29 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ "WORLD REPORT | 2014" (PDF). Report. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Treasury Targets Hizballah in Venezuela". Press Release. United State Department of Treasury. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Treasury Targets Venezuelan Government Officials Supporting the FARC". Press Release. United States Department of Treasury. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Sanchez, Nora (15 February 2014). "Detienen a comandante de la Milicia con cargamento de drogas". El Universal. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ Reel, M. "Crime Brings Venezuelans Into Streets". Washington Post (10 May 2006), p. A17. Accessed 24 June 2006.

- ^ Wills, Santiago (10 July 2013). "The World Is Getting More Corrupt, and These Are the 5 Worst Offenders". Fusion. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Venezuela: Police corruption blamed for kidnapping epidemic". The Scotsman. 30 May 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Beckhusen, Robert (20 February 2014). "Pro-Government Motorcycle Militias Terrorize Venezuela". Medium. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

Further reading

- Venezuela Corruption Profile from the Business Anti-Corruption Portal

- Gregory Wilpert (November–December 2006). "Corrupt Data". Extra!.

- Kiraz Janicke (18 June 2008). "Venezuela's Electoral Council to Respect Disqualification of Candidates Accused of Corruption". Venezuela Analysis.