Clothing in the ancient world

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The clothing used in the ancient world strongly reflects the technologies that these peoples mastered. Archaeology plays a significant role in documenting this aspect of ancient life, for fabric fibres, and leathers sometimes are well-preserved through time. In many cultures the clothing worn was indicative of the social status achieved by various members of their society.

Origin of Clothing System

The attire fashion and clothing is exclusively human characteristic and is a feature of most human societies. In the most ancient days, humans started to implement clothing system to protect their body from heat, sun, rain, cold, etc. and animal skins and vegetation were mainly used as materials to cover their bodies. Clothing and textiles in different periods and ages reflect the development of civilization and technologies in different periods of time at different places. Sources available for the study of clothing and textiles include material remains discovered via archaeology; representation of textiles and their manufacture in art; and documents concerning the manufacture, acquisition, use, and trade of fabrics, tools, and finished garments.

Ancient Egyptian clothing

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as it contains no references, and consists mostly of dubious, uncited material- See discussion. (August 2013) |

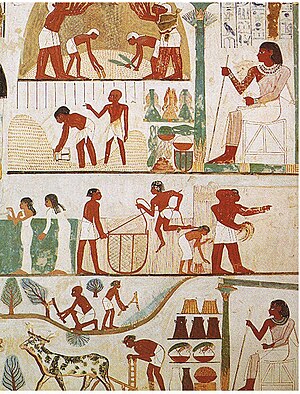

In Ancient Egypt, flax was the textile in almost exclusive use. Wool was known, but considered impure as animal fibres were considered taboo, and could only be used for coats (they were forbidden in temples and sanctuaries). People of lower class wore only the loincloth (or schenti) that was common to all. Shoes were the same for both sexes; sandals braided with leather, or, particularly for the bureaucratic and priestly classes, papyrus. The most common headgear was the kaftan, a striped fabric square worn by men. Feather headdresses were worn by the nobility.

Certain clothing was common to both genders such as the tunic and the robe. Around 1425 to 1405 BCE, a light tunic or short-sleeved shirt was popular, as well as a pleated skirt.

Clothing for adult women remained unchanged over several millennia, save for small details. Draped clothes, with very large rolls, gave the impression of wearing several items. It was in fact a hawk, often of very fine muslin[dubious – discuss]. The dress was rather narrow, even constricting, made of white or unbleached fabric for the lower classes, the sleeve starting under the chest in higher classes, and held up by suspenders tied onto the shoulders. These suspenders were sometimes wide enough to cover the breasts and were painted and colored for various reasons, for instance to imitate the plumage on the wings of Isis.

Clothing of the royal family was different, and was well documented; for instance the crowns of the pharaohs (see links below), the nemes head dress, and the khat or head cloth worn by nobility.

Perfume and cosmetics

Embalming made it possible to develop cosmetic products and perfumery very early. Perfumes in Egypt were scented oils which were very expensive. In antiquity, people made great use of them. The Egyptians used make-up much more than anyone else at the time. Kohl, used as eyeliner, was eventually obtained as a substitute[dubious – discuss] for galena or lead oxide which had been used for centuries. Eye shadow was made of crushed malachite and lipstick of ochre. Substances used in some of the cosmetics were toxic, and had adverse health effects with prolonged use. Beauty products were generally mixed with animal fats in order to make them more compact, more easily handled and to preserve them. Nails and hands were also painted with henna[dubious – discuss]. Only the lower class had tattoos[dubious – discuss]. It was also fashionable at parties for men and women to wear a perfumed cone on top of their heads. The cone was usually made of ox tallow and myrrh and as time passed, it melted and released a pleasant perfume. When the cone melted it was replaced with a new one (see the image to the right with the musician and dancers).

Wigs

Wigs were used by both sexes of the upper class. Made of real hair, they contained other decorative elements. In the court, the more elegant examples had small goblets at the top filled with perfume. Heads were shaven; shaved heads are a sign of nobility.[1] Usually children were represented with one lock of hair remaining on the sides of their heads (see the image to the right).

Ornaments

Wigs contained ornamental decorations. A peculiar ornament which the Egyptians created was gorgerin[dubious – discuss], an assembly of metal discs which rested on the chest skin or a short-sleeved shirt, and tied at the back. Some of the lower-class people of this time also created many different types of piercings and body decorations[dubious – discuss]; some of which even included genital piercings, commonly found on women prostitutes of the time[dubious – discuss].

Jewelry

Jewels were heavy and rather bulky, which would indicate an Asian influence[dubious – discuss]. The lower classes wore small and simple glassware; bracelets also were heavy. The most popular stones used were Lapis Lazuli, Carnelian, and Turquoise. They wore a large disk as a necklace of strength, sometimes described as an aegis. Gold was plentiful in Nubia and imported for jewelry and other decorative arts.

(Egypt) See also

Ancient Minoan clothing

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

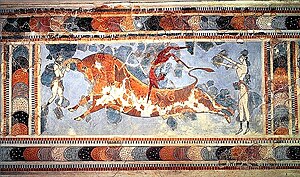

As elsewhere, Cretan clothes in the ancient times were well documented in their artwork where many items worn by priestesses and priests seem to reflect the clothing of most. Wool and flax were used. Spinning and weaving were domestic activities, dyeing was the only commercial process in keeping with everywhere else in antiquity. Fabrics were embroidered. Crimson was used the most in dyeing, in four different shades.

Female Minoan dress

Early in the culture, the loincloth was used by both sexes. The women of Crete wore the garment more as an underskirt than the men, by lengthening it. They are often illustrated in statuettes with a large dagger fixed at the belt. The provision of items intended to secure personal safety was undoubtedly one of the characteristics of female clothing in the Neolithic era[dubious – discuss], traces of the practice having been found in the peat bogs of Denmark up to the Bronze Age.

From 1750 BC, the long skirt was trimmed and began to resemble the blouse in appearance. The belt, a long or short coat, and a hat supplemented the female outfit. Cretan women's clothing included the first sewn garments known to history. Ancient brooches, widespread in the Mediterranean, were used throughout the period.

Dresses too were long and low-necked, like those of the 19th century. They were so low that the bodice was open almost all the way to the waist.

Male Minoan dress

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (February 2012) |

Practically all men wore a loincloth. Unlike the Egyptians, the shanti varied according to its cut and normally was arranged as a short skirt or apron, ending in a point sticking out similar to a tail. The fabric passed between the legs, adjusted with a belt, and almost certainly, was decorated with metal. It was worn by all men in society.

In addition to Cretan styles, Cycladelic clothing was worn as pants across the continent. A triangular front released the top of the thighs. One could say it was clothing of an athletic population, because of this and the fact that the chest always was naked. It was sometimes covered with a cask, probably ritualistically. However, long clothing was worn for protection against bad weather and eventually a coat of wool was used by the Greeks.

Men had long hair flowing to the shoulders; however several types of headgear were usual, types of bonnets and turbans, probably of skin. Shoes were boots of skin, probably of chamois, and were used only to leave the house, where one went barefoot, just as in the sanctuaries and the palaces. People studying this matter have noticed the outdoor staircases are worn down considerably, interior ones hardly at all. It's known that later, entering a house - this habit already was in use in Crete. The boots had a slightly raised end, thus indicating an Anatolian origin, similar to those found on the frescoes of Etruria

Ancient Israelite clothing

Israelite man

Undergarments

The earliest and most basic garment was the 'ezor (ay-ZOHR)[2] or ḥagor (kha-GOHR),[3] an apron around the hips or loins,[4] that in primitive times was made from the skins of animals.[5] It was a simple piece of cloth worn in various modifications, but always worn next to the skin.[4] Garments were held together by a belt or girdle, also called an 'ezor or ḥagor.[5]

The 'ezor later became displaced among the Hebrews by the kuttoneth (ke-TOH-neth).[6] an under-tunic.[4][5] The kuttoneth appears in Assyrian art as a tight-fitting undergarment, sometimes reaching only to the knee, sometimes to the ankle. [4] The kuttoneth corresponds to the undergarment of the modern Middle Eastern agricultural laborers: a rough cotton tunic with loose sleeves and open at the breast.[4] Anyone dressed only in the kuttoneth was considered naked.[5]

Outer garments

- simla

The simla (sim-LAH)[7] was the heavy outer garment or shawl of various forms.[4] It consisted of a large rectangular piece of rough, heavy woolen material, crudely sewn together so that the front was unstitched and with two openings left for the arms.[4][5] Flax is another possible material.[5]

In the day it was protection from rain and cold, and at night peasant Israelites could wrap themselves in this garment for warmth[4][5] (see Deuteronomy 24:13). The front of the simla also could be arranged in wide folds (see Exodus 4:6) and all kinds of products could be carried in it[4][5] (See 2Kings 4:39, Exodus 12:34).

Every respectable man generally wore the simla over the kuttoneth (See Isaiah 20:2–3), but since the simla hindered work, it was either left home or removed when working.[4][5] (See Matthew 24:18). From this simple item of the common people developed the richly ornamented mantle of the well-off, which reached from the neck to the knees and had short sleeves.[4]

- me'il

The me'il (me-EEL)[8] or cloak was generally worn over the undergarment,[5] (See 1Samuel 2:19, 1Samuel 15:27). The me'il was a costly wrap (See 1Samuel 2:19, 1Samuel 18:4, 1Samuel 24:5, 1Samuel 24:11) and, according to the description of the priest's me'il, was similar to the sleeveless abaya (Exodus 28:31).[4] This, like the me'il of the high priest, may have reached only to the knees, but it is commonly supposed to have been a long-sleeved garment made of a light fabric, probably imported from Syria.[5]

Religious wear

The Torah commands that Israelites wear tassels or fringes (ẓiẓit, tsee-TSEET[9] or gedilim, ghed-EEL[10]) attached to the corners of garments (see Deuteronomy 22:12, Numbers 15:38).

Phylacteries or tefillin (Hebrew: תְפִלִּין) are in use by New Testament times (see Matthew 23:5). Tefillin are boxes containing biblical verses that are attached to the forehead and arm by leather straps.[11]

Headwear

Depictions show some Hebrews and Syrians bareheaded or wearing merely a band to hold the hair together.[4] Hebrew peasants undoubtedly also wore head coverings similar to the modern keffiyeh, a large square piece of woolen cloth folded diagonally in half into a triangle.[4] The fold is worn across the forehead, with the keffiyeh loosely draped around the back and shoulders, often held in place by a cord circlet. Men and women of the upper classes wore a kind of turban, cloth wound about the head. The shape varied greatly.[4]

Footwear

Sandals (na'alayim) of leather were worn to protect the feet from burning sand and dampness.[5] Sandals might also be of wood, with leather straps (Genesis 14:23, Isaiah 5:27).[4] Sandals were not worn in the house nor in the sanctuary[4][5] (see Exodus 3:5, Joshua 5:15).

Israelite women

A woman's garments mostly corresponded to those of men: they wore simla and kuttoneth.[4][5] Women's garments evidently differed too from that of a men[4][5] (see Deuteronomy 22:5). Women's garments were probably longer (compare Nahum 3:5, Jeremiah 13:22, Jeremiah 13:26, Isaiah 47:2), had sleeves (2Samuel 13:19), presumably were brighter colors and more ornamented, and may also have been of finer material.[4][5]

Further, mention is made of the mițpaḥațh, a kind of veil or shawl (Ruth 3:15). This was ordinarily just a woman's neckcloth. Other than the use by a bride (Genesis 24:65) and other cases (Genesis 38:14, Ruth 3:3), a woman did not go veiled (Genesis 12:14, Genesis 24:15). The present custom in the Middle East to veil the face are due to Islam. According to ancient laws, it reached from the forehead, over the back of the head to the hips or lower, and was like the neckerchief of the peasant woman in Palestine today.[4]

Ancient Greek clothing

Ancient Greece is famous for its philosophy, art, literature, and politics. As a result, classical period Greek style in dress often has been revived when later societies wished to evoke some revered aspect of ancient Greek civilization, such as democratic government. A Greek style in dress became fashionable in France shortly after the French Revolution (1789–1799), because the style was thought to express the democratic ideals for which that revolution was fought, no matter how incorrect the understanding of the historical reality was.

Clothing reformers later in the 19th century admired ancient Grecian dress because they thought it represented timeless beauty, the opposite of complicated and rapidly changing fashions of their time, as well as the more practical reasoning that Grecian-style dresses required far less cloth than those of the Rococo period.

Clothing in ancient Greece primarily consisted of the chiton, peplos, himation, and chlamys. While no clothes have survived from this period, descriptions exist from contemporary accounts and artistic depiction. Clothes were mainly homemade, and often served many purposes (such as bedding). Despite popular imagination and media depictions of all-white clothing, elaborate design and bright colors were favored.[12]

Ancient Greek clothing consisted of lengths of linen or wool fabric, which generally was rectangular. Clothes were secured with ornamental clasps or pins (περόνη, perónē; cf. fibula), and a belt, sash, or girdle (zone) might secure the waist.

- Peplos, Chitons

The inner tunic was a peplos or chiton. The peplos was a worn by women. It was usually a heavier woollen garment, more distinctively Greek, with its shoulder clasps. The upper part of the peplos was folded down to the waist to form an apoptygma. The chiton was a simple tunic garment of lighter linen, worn by both genders and all ages. Men's chitons hung to the knees, whereas women's chitons fell to their ankles. Often the chiton is shown as pleated. Either garment could be pulled up under the belt to blouse the fabric: kolpos.

- Strophion, Epiblema, Veil

A strophion was an undergarment sometimes worn by women around the mid-portion of the body, and a shawl (epiblema) could be draped over the tunic. Women dressed similarly in most areas of ancient Greece although in some regions, they also wore a loose veil as well at public events and market.

- Chlamys

The chlamys was made from a seamless rectangle of woolen material worn by men as a cloak. The it was about the size of a blanket, usually bordered. The chlamys was typical Greek military attire from the 5th to the 3rd century BC. As worn by soldiers, it could be wrapped around the arm and used as a light shield in combat.

- Himation

The basic outer garment during winter was the himation, a larger cloak worn over the peplos or chlamys. The himation has been most influential perhaps on later fashion.

- Athletics and nudity

During Classical times in Greece, male nudity received a religious sanction following profound changes in the culture. After that time, male athletes participated in ritualized athletic competitions such as the classical version of the ancient Olympic Games, in the nude as women became barred from the competition except as the owners of racing chariots. Their ancient events were discontinued, one of which (a footrace for women) had been the sole original competition. Myths relate that after this prohibition, a woman was discovered to have won the competition while wearing the clothing of a man—instituting the policy of nudity among the competitors that prevented such embarrassment again.

Ancient Roman and Italic clothing

The clothing of ancient Italy, like that of ancient Greece, is well known from art, literature & archaeology. Although aspects of Roman clothing have had an enormous appeal to the Western imagination, the dress and customs of the Etruscan civilization that inhabited Italy before the Romans are less well imitated (see the image to the right), but the resemblance in their clothing may be noted. The Etruscan culture is dated from 1200 BC through the first two phases of the Roman periods. At its maximum extent during the foundation period of Rome and the Roman kingdom, it flourished in three confederacies of cities: of Etruria, of the Po valley with the eastern Alps, and of Latium and Campania. Rome was sited in Etruscan territory. There is considerable evidence that early Rome was dominated by Etruscans until the Romans sacked Veii in 396 BC.

In Ancient Rome, boys after the age of sixteen had their clothes burned as a sign of growing up.[13] Roman girls also wore white until they were married to say they were pure and virginal.[14]

Toga and tunics

Probably the most significant item in the ancient Roman wardrobe was the toga, a one-piece woolen garment that draped loosely around the shoulders and down the body. Togas could be wrapped in different ways, and they became larger and more voluminous over the centuries. Some innovations were purely fashionable. Because it was not easy to wear a toga without tripping over it or trailing drapery, some variations in wrapping served a practical function. Other styles were required, for instance, for covering the head during ceremonies.

Historians believe that originally the toga was worn by all Romans during the combined centuries of the Roman monarchy and its successor, the Roman Republic. At this time it is thought that the toga was worn without undergarments.[citation needed] Free citizens were required to wear togas.[13] because only slaves and children wore tunics.[15] By the 2nd century BC, however, it was worn over a tunic, and the tunic became the basic item of dress for both men and women. Women wore an outer garment known as a stola, which was a long pleated dress similar to the Greek chitons.

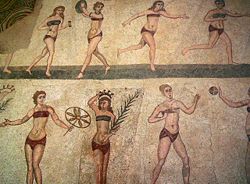

Although togas are now thought of as the only clothing worn in ancient Italy, in fact, many other styles of clothing were worn and also are familiar in images seen in artwork from the period. Garments could be quite specialized, for instance, for warfare, specific occupations, or for sports. In ancient Rome women athletes wore leather briefs and brassiere for maximum coverage but the ability to compete.[15]

Girls and boys under the age of puberty sometimes wore a special kind of toga with a reddish-purple band on the lower edge, called the toga praetexta. This toga also was worn by magistrates and high priests as an indication of their status. The toga candida, an especially whitened toga, was worn by political candidates. Prostitutes wore the toga muliebris, rather than the tunics worn by most women. The toga pulla was dark-colored and worn for mourning, while the toga purpurea, of purple-dyed wool, was worn in times of triumph and by the Roman emperor.

After the transition of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire in c. 44 BC, only men who were citizens of Rome wore the toga. Women, slaves, foreigners, and others who were not citizens of Rome wore tunics and were forbidden from wearing the toga. By the same token, Roman citizens were required to wear the toga when conducting official business. Over time, the toga evolved from a national to a ceremonial costume. Different types of togas indicated age, profession, and social rank. Roman writer Seneca criticized men who wore their togas too loosely or carelessly. He also criticized men who wore what were considered feminine or outrageous styles, including togas that were slightly transparent.

The late toga of adult citizens, the toga virilis, was made of plain white wool and worn after the age of fourteen. A woman convicted of adultery might be forced to wear a toga as a badge of shame and curiously, as a symbol of the loss of her female identity.

The ancient Romans were aware that their clothing differed from that of other peoples. In particular, they noted the long trousers worn by people they considered barbarians from the north, including the Germanic Franks and Goths. The figures depicted on ancient Roman armored breastplates often include barbarian warriors in shirts and trousers.

-

Mosaic of ancient women dressed for sports - Roman villa near Piazza Armerina - Sicily

-

Livia Drusilla (58 BC–29 AD) wearing a stola and palla - early 1st century - Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España, Madrid

-

Augustus (63 BC–14 AD) wearing a toga and calcei patricii (shoes reserved for Patricians), a capsa (container for documents) lies at his feet - late 1st century AD - Museo Nazionale Romano Rome

Symbolism and influence

Roman clothing took on symbolic meaning for later generations. Roman armour, particularly the muscle cuirass, has symbolized amazing power. In Europe during the Renaissance (15th and 16th centuries), painters and sculptors sometimes depicted rulers wearing pseudo-Roman military attire, including the cuirass, military cloak, and sandals.

Later, during the French Revolution, an effort was made to dress officials in uniforms based on the Roman toga, to symbolize the importance of citizenship to a republic. Adopted by the rank and file revolutionaries, the 18th-century liberty cap, a brimless, limp cap fitting snugly around the head, was based on a bonnet worn by freed slaves in ancient Rome, the Phrygian cap.

The modern Western bride also has inherited elements from ancient Roman wedding attire, such as the bridal veil and the wedding ring.

Ancient Indian Clothing

Introduction

Clothing System in India

Indians wore mainly clothing made up of cotton of locally grown. India was the one of the first places where cotton was cultivated and used even as early as 2500 during the Harappan Era. The remnants of the ancient Indian clothing can be found in the figurines discovered from the sites of the Indus valley civilization, the rock cut sculptures, the cave paintings, and human art forms found in temples and monuments. These scriptures show the figures of human wearing the clothes which can be wrapped around the body. Taking the instances of the Sari to that of turban and the dhoti, the traditional Indian wears were mostly tied around the body in various ways.

Clothing and Socio-economic Status

The clothing system was also related to the social and economic status of the person. The upper classes of the society wore fine muslin garments and silk fabrics while the common classes wore garments made up of locally made fabrics. For instance, Women from Rich families wore clothes (Sari specifically) made up of silk from China, but the common women wore sari made up of cotton or local fabrics. The Indus civilization knew the process of silk production. Recent analysis of Harappan silk fibres in beads have shown that silk was made by the process of reeling, the art known only to China till the early centuries AD.

Clothing in Indus Valley Civilization Period

Evidences for textiles in Indus valley civilization are not available from preserved textiles but from impressions made into clay and from preserved pseudomorphs. The only evidence found for clothing is form iconography and some unearthed Harappan figurines which are usually unclothed. These little depictions show that usually men wore a long cloth wrapped over their waste and fastened it at the back (just like a close clinging dhoti). Turban was also in custom in some communities as shown by some of the male figurines. Evidences also show that there was a tradition of wearing a long robe over the left shoulder in higher class society to show their opulence. The normal attire of the women at that time was a very scanty skirt up to knee length leaving the waist bare. Cotton made head dresses were also worn by the women.

Fibre for clothing generally used were cotton, flax, silk, wool, linen, leather, etc. one fragment of coloured cloth is available in evidences which is dyed with red madder show that people in Harappan civilization dyed their cotton clothes with a range of colours.

One thing was common in both the sexes that both men and women were fond of jewellery. The ornaments include necklaces, bracelets, earrings, anklet, rings, bangles, pectorals, etc. which were generally made of gold, silver, copper, stones like lapis lazuli, turquoise, Amazonite, quartz, etc. Many of the male figurines also reveal the fact that men at that time were interested in dressing their hair in various styles like the hair woven into a bun, hair coiled in a ring on the top of the head, beards were usually trimmed.

Clothing in Vedic Period

The Vedic age or the Vedic period was the time duration between 1500 to 500 BC

The garments worn in Vedic period mainly included a single cloth wrapped around the whole body and draped over the shoulder. People used to wear the lower garment called Paridhana which was pleated in front and used to tie with a belt called Mekhala and an upper garment called Uttariya (covered like a shawl) which they used to remove during summers. Orthodox males and females usually wore the uttariya by throwing it over the left shoulder only, in the style called upavita.[16] There was another garment called Pravara that they used to wear in cold. This was the general garb of both the sexes but the difference existed only in size of cloth and manner of wearing. Sometimes the poor people used to wear the lower garment as a loincloth only while rich used to wear it up to their feet to brag their prestige off in society.

Sari was the main costume for women in Vedic culture. Women used to wrap it around their waste, pleated in front over the bailey and drape it over their shoulder covering their bust area and fastened it with a pin at the shoulder. ‘Choli’or blouse, as an upper garment was introduced in the later Vedic period with sleeves and a neck. A new version of sari, little smaller than sari, called Dupatta, was also incorporated later and it was used to wear along with Ghaghara (frilled skirt up to feet). The word sari is derived from Sanskrit शाटी śāṭī[17] which means 'strip of cloth'and शाडी śāḍī or साडी sāḍī in Prakrit, and became sāṛī in Hindi. Most initial attires of men in those times were Dhoti and Lungi. Dhoti is basically a single cloth wrapped around the waist and by partitioning at the centre, is fastened at the back. A dhoti is from four to six feet long white or colour strip of cotton.[18] Generally, in those times, no upper garment was worn and Dhoti was the only single clothing that men used to drape it over their bodies. Later on, many costumes evolved like kurtas, pajamas, trousers, turbans, etc. Wool, linen, diaphanous silks and muslin were the main fibres used for making cloth and patterns with gray strips and checks were made over clothes.

The 11th-century BCE Rig-veda mentions dyed and embroidered garments (known as paridhan and pesas respectively) and thus highlights the development of sophisticated garment manufacturing techniques during this period.[19]In the Rig Veda, mainly three terms were described like Adhivastra, Kurlra and Andpratidhi for garments which correspondingly denotes the outer cover (veil), a head-ornament or head-dress (turban) and part of woman's dress. Many evidences are found for ornaments like Niska, Rukma were used to wear in the ear and neck; there was a great use of gold beads in necklaces which show that gold was mainly used in jewellery. Rajata-Hiranya (white gold), also known as silver was not in that much of use as no evidence of silver is figured out in the Rig Veda.

In the Atharva Veda, garments began to be made of inner cover, an outer cover and a chest-cover. Besides Kurlra and Andpratidhi (which already mentioned in the Rig Veda), there are other parts like as Nivi, Vavri, Upavasana, Kumba, Usnlsa, and Tirlta also appeared in Atharva Veda, which correspondingly denotes underwear, upper garment, veil and the last three denoting some kinds of head-dress (head-ornament). There were also mentioned Updnaha (Footwear) and kambala (blanket) , Mani (jewel) is also mentioned for making ornaments in this Vedic text.

Clothing in Mauryan period

TheMauryan dynasty (322-185 B.C.E.) was one of the largest empires in the world in its time. Evidences of women clothing in Mauryan times is available from the statues of Yakshis, the female epitome of fertility. The most common attire of the people at that time was antariya, which they used to wear as a lower garment. Generally made of cotton, linen or muslin and decorated with gemstone, it is fastened at the centre of the waist tied in a looped knot. A cloth was covered in lehnga style around the hips to form a tubular skirt. An embellished long piece of cloth, hanging at the front, wrapped around the waist is pleated into the antariya is called patka. Ladies in the Mauryan Empire often used to wear an embroidered fabric waistband with drum headed knots at the ends. As an upper garment, people’s main garb was uttariya, a long scarf. The difference existed only in the manner of wearing. Sometimes, its one end is thrown over one shoulder and sometimes it is draped over both the shoulders.

In textiles, mainly cotton, silk, linen, wool, muslin, etc. are used as fibres. Ornaments latched on to a special place in this era also. Some of the jewelleries had their specific names also. Satlari, chaulari, paklari were some of the necklaces. Similarly, bajuband, kangan, sitara, patna were also prominent during that time.

Clothing in Gupta Period

The Gupta period is called the golden age of India lasted from 320 AD to 550 AD. Chandragupta was the founder of this empire. Stitched garments became very popular in this period only. Stitched garment became the sign of royalty. But antariya, uttariya, and other cloth still were in use.

Gradually, the antariya worn by the women turned into gagri, which has many swirling effects exalted by its many folds. That’s why, dancers used to wear it a lot. As it is evident from many sources, women used to wear only the lower garment in those times, leaving the bust part bare. Later on, various kinds of blouses (Cholis) evolved. Some of them had strings attached leaving the back open while others was used to tie from front side, exposing the midriff. Calanika was an antariya which could be worn as kachcha and lehnga style together. Women sometimes wore antariya in saree style, throwing one end of it over the shoulder, but the main feature is that they did not use it to cover their heads as it was prominent in earlier periods.

Clothing in Gupta period mainly comprised of cut and sewn garments. A long sleeved brocaded tunic[20] became the main costume for privileged people like the nobles and courtiers. The main costume for the king was most often a blue closely woven silk antariya, perhaps with a block printed pattern. In order to tight the antariya, a plane belt took the position of kayabandh. Mukatavati (necklace which has a string with pearls), kayura (armband), kundala (earring), kinkini (small anklet with bells), mekhala (pendant hung at the centre, also known as katisutra), nupura (anklet made of beads) were some of the ornaments made of gold, used in that time. There was an extensive use of ivory during that period for jewellery and ornaments.

During Gupta period, men use to have long hair along with beautiful curls and this style was popularly known as gurna kuntala style. In order to decorate their hair, they sometimes put headgear, a band of fabric around their hairs. On the other hand, women used to decorate their hairs with luxuriant ringlets or a jewelled band or a chaplet of flowers. They often used to make a bun on the top of head or sometimes low on the neck, surrounded by flowers or ratnajali (bejewelled net) or muktajala (net of pearls).

Clothing in Mughal period

Mughal dynasty was one of the greatest empires in India. Their uxurious and relaxed life are the proofs of their impassioned interest towards art, poetry and textile as well. Both the ladies and gents were fond of jewellery and their dressing style was highly alluring. Their clothing fibers generally included muslin which is again of three types: Ab-e-Rawan (running water), Baft Hawa (woven air) and Shabnam (evening dew) and the other fibers were silks, velvets and brocades. Besides being beautiful and expensive, these Mughal royal dresses consisted of many parts as listed below.-

Mughal men clothing

Jama: this was considered as the man royal garb of Mughal emperors. It is a tight fitting frock coat with flared skirt up to knee length fastened on the right side of the body.

Patka: for keeping the jeweled sword around the waist of Jama, Patka is used. It is a type of girdle made of a fine fiber which is hand- painted, printed or embroidered.

Chogha: these are embroidered long sleeved coats generally worn over Jamas, Angrakhas and other garments. It is generally up to knee length and is open from the front.

Pagri or turban: this was the main attire of mughals as it proclaims their status, their standard in society. To give turban to somebody means you are vanquishing your powers of them. On the other hand, removal of turban was considered as a mortifying punishment that could be given to ay Indian man.

Mughal women clothing

Mughal women loaded themselves with a large variety of ornaments from head to toe. Their costumes generally include Peshwaj, Yalek, Pa-jama, Churidar, Shalwar, Dhilija, Garara, Farshi. Among them, manly include head ornaments, anklets, and necklaces. Ornaments were like a thing of pleasure for them. This was also the distinctive mark of their prosperity, their rank and dignity in society. Caps were worn by Mughal women also and were available in various styles. In Mughal times, there was a great tradition of wearing embroidered footwear’s, ornamented on leather and also implicated with the art of Aughi. In those times, Lucknow footwear were generally liked by the noble and kings.

Clothing in Rajput period

Rajputs emerged in 7th and 8th century as a new community of Kshatriya people. Rajputs followed a traditional life style for living which shows their martial spirit, ethnicity and chivalric grandeur.

Men's Clothing

Rajputs’ main costumes were the aristocratic dresses (court-dress) which includes Angarkhi, pagdi, chudidar pyjama and a cummerbund (belt). Angarkhi (short jacket) is long upper part of garments which they used to wear over a sleeveless close fitting cloth. Nobles of Rajputs generally attired themselves in the Jama, Shervani as an upper garment and Salvar, Churidar-Pyjama (a pair of shaped trousers) as lower garments. The Dhoti was also in tradition in that time but styles were different to wear it. Tevata style of dhoti was prominent in Desert region and Tilangi style in the other regions.

Women's Clothing

Rajput women's main attire was the Sari (wrapped over whole body and one of the end thrown on the right shoulder) or Lengha related with the Rajasthani traditional dress. On the occasion (marriage) women preferred Angia. After marriage of Kanchli, Kurti, and angia were the main garb of women. The young girls used to wear the Puthia as an upper garment made of pure cotton fabric and the Sulhanki as lower garments (loose pyjama). Widows and unmarried women clothed themselves with Polka (half sleeved which ends at the waist) and Ghaghra as a voluminous gored skirt made of line satin, organza or silk. Other important part of clothing is Odhna of women which is worked in silk.

Jewelleries preferred by women were exquisite in the style or design. One of the most jewellery called Rakhdi (head ornament), Machi-suliya (ears) and Tevata, Pattia, and the aad (all is necklace). Rakhdi, nath and chuda shows the married woman's status. The footwear is same for men and women and named Juti made of leather.

Women's clothing and orthodox

Many myths related to women clothing were prevalent in orthodox Indian society. One of them was Purdah pratha. More simply, it is the practice of preventing men from seeing the women. During that time, it was not considered ethical if a woman appears before a man without covering her face. The system was not a part of ancient Hindu life at all. [21]. But it was adopted by middle and upper class Hindu during the Mughal and British rule, to improve their position in the social hierarchy. In this system, women cover their faces completely so can no male member of their house or of the society can see their faces. Even their sons were not allowed to see their faces. It was mainly prevalent in northern India, and it is an indisputable fact that during the war and foreign domination, women are often raped and kidnapped. That’s why we can have the glimpses of the system in some parts of North India. In fact, this system has become a ritual in some communities.

See also

References

- ^ http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Wigs.aspx#1

- ^ "'ezowr". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "Chagowr". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Dress and Ornament, Hebrew". Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Baker Book House. 1907.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: External link in|title= - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Costume: In Biblical Times". Jewish Encyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls. 1901.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: External link in|title= - ^ "K@thoneth". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Biblestudytools.com Hebrew lexicon: simlah; The Hebrew lexicon is Brown, Driver, Briggs, Gesenius Lexicon. See also salmah.

- ^ "M@`iyl". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Biblestudytools.com Hebrew lexicon: ẓiẓit; The Hebrew lexicon is Brown, Driver, Briggs, Gesenius Lexicon

- ^ "G@dil". BibleStudyTools.com. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Tefillin, "The Book of Jewish Knowledge", Nathan Ausubel, Crown Publishers, NY, 1964, p.458

- ^ "Ancient Greek Dress". Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ a b Steele,Philip. "Clothes and Crafts in Roman Times". Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2000, p. 20

- ^ Steele,Philip. "Clothes and Crafts in Roman Times". Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2000, p. 23

- ^ a b Steele,Philip. "Clothes and Crafts in Roman Times". Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2000, p. 21

- ^ Ayyar, Sulochana (1987). Costumes and Ornaments as Depicted in the Sculptures of Gwalior Museum. Mittal Publications. pp. 95–96.

- ^ R. S. McGregor, ed. (1997). The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 1003. ISBN 978-0-19-864339-5.

- ^ Michael Dahl (January 2006). India. Capstone Press. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-0-7368-8374-0. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ Verma, S.P. (2005). Ancient system of oriental medicine. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 81-261-2127-0.

- ^ Alkazi, Roshen. Ancient India Costume. Paperback(Edition:2010). p. 87. ISBN 9788123716879.

- ^ "Rajput". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2014.