History of Sindh

| History of Sindh |

|---|

|

| History of Pakistan |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

The history of Sindh or Sind (Sindhi: سنڌ جي تاريخ, Urdu: سندھ کی تاریخ) is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and surrounding regions. Sindh was at the center of the Indus Valley civilization, one of the cradle of civilization; and currently a province of modern-day Pakistan.

Vedic Era

Indus Valley Civilisation

It is believed by most scholars that the earliest trace of human inhabitation in India traces to the Soan valley between the Indus and the Jhelum rivers. This period goes back to the first inter-glacial period in the Second Ice Age, and remnants of stone and flint tools have been found.[1]

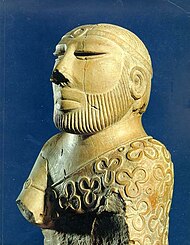

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand year old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Hundreds of settlements have been found spanning an area of about a hundred miles. These ancient towns and cities had advanced features such as city-planning, brick-built houses, sewage and draining systems, as well as public baths. The people of the Indus Valley also developed a writing system, that has to this day still not been fully deciphered.[2] The people of the Indus Valley had domesticated bovines, sheep, elephants, and camels. The civilization also had knowledge of metallurgy. Gold, silver, copper, tin, and alloys wre widely in use. Arts and crafts flourished during this time as well; the use of beads, seals, pottery, and bracelets are evident.[3]

Vedic Descriptions

Literary evidence from the Vedic era suggests a transition from early small janas, or tribes, to many Janapadas (territorial civilizations) and gana-samgha societies. The gana samgha soceties are loosely translated to being oligarchies or republics. These political entities were represented from the Rig Veda to the Astadhyayi by Panini.[4] Many Janapadas were mentioned from vedic texts and are confirmed by Ancient Greek historical sources. Most of the Janapadas that had exerted large territorial influence, or Mahajanapadas, had been raised in the Indo-Gangetic plain with the exception of Gandhara in modern-day Afghanistan. There was a large level of contact between all the Janapadas of ancient India with descriptions being given of trading caravans, movement of students from universities, and itineraries of Princes.[5]

Mauryan Era

Chandragupta Maurya, with the aid of Kautilya, had established his empire around 320 B.C. The early life of Chandragupta Maurya is not clear. Kautilya took a young Chandragupta to the University at Taxila and enrolled him in order to educate him in the arts, sciences, logic, mathematics, warfare, and administration. Chankya's main task was to liberate India from Greek rule. With the help of the small Janapadas of Punjab and Sindh, he had went on to conquer much of the North West. He then defeated the Nanda rulers in Pataliputra to capture the throne. Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[6]

Mauryan rule was advanced for its time, and foreign accounts of Indian cities mention many temples, libraries, universities, gardens, and parks. A notable account was that of the Greek ambassador Megasthenes who had visited the Mauryan capital of Pataliputra. Chandragupta's rule was a very well organized one. The Mauryans had a strong centralized government with a competent bureaucracy. This bureaucracy had concerned itself with the affairs of tax collection, trade and commerce, industrial activities, mining, statistics and data, maintenance of public places, and upkeep of temples.[6]

The Mauryan Empire was greatly weakened following the death of Ashoka. The dynasty lasted until c.184 B.C when the commander-in-chief captured the throne from Brihadratha. What remained under the power of the Mauryans was ruled by the subsequent Sunga dynasty. [7]

Islamic Invasions

Arab Invasions

The Islamic conquest of half of the known world within 50 years, immediately after the death of the Prophet Mohammed, has been described as one of the most noteworthy events in history. Motivated by the desire to convert other people to the faith, the Muslims conquered North Africa, Spain, and other surrounding areas; as well as destroying the Persian Empire. The only area that was able to resist much of the invasions was India, with the first invasion at Sindh being repelled. [8][9]

In 712, Mohammed Bin Qasim advanced to Sindh with his army. Debal was the first to fall to Qasim; and Raja Dahir, the ruler of the area, did not make any preparation for defence. The inhabitants of the city were forced to convert to Islam, and those who refused were slain or sold in to slavery. Almost all young men were executed, and the women and children were sold into slavery. [10] [unreliable source?]

After his victory, Qasim marched to the fort of Nerun. The son of the Raja had left his son under command of Nerun, who had in turn given control of the fort to one of his commanders. Qasim next marched onto Sehwan, which had surrendered after a week's siege. After taking Brahmanabad, Qasim marched towards Rawer; at this point, the army of Raja Dahir stood face to face with that of the Arab general.Dahir was killed on the battlefield, and the Queen had subsequently attempted to resist the invasion. After defeat, the Queen chose to perform Sati. Other accounts mention that Mohammed Qasim had taken Queen Ladi to be his wife. Parmaldevi and Asuryadevi, the daughters of the royal family, were taken to the Caliph and were reportedly taken of their chastity. [11] [12]

The later Arab governors of Sindh had made continuous efforts to extend their territory. Junaid, the successor to Qasim, had in 725 attempted to conquer Gujarat and Malwa. Though initially successful, the campaign had failed to achieve its objective. In 731, Junaid's successor Tameem had attempted to attack the Deccan. This endeavor had failed as well, due to the defeat of the Muslims by Pulikesena Chalukya at Navasari in 738. These failures did not stop the Islamic armies, as a later attack had reportedly reached as far as Ujjain. This attack was later replled by the Gurjara king Nagabhata. [13] After Nagabhata's victory, Islam was not to be a threat to India in another three centuries. Various warring Hindu kings had control of the region, and were oblivious to external threats.[14]

Some of the territory in Sindh found itself under raid from the Ghaznavid Empire.In 974 Pirin, the slave-governor of Ghazni, repulsed a force sent from India to seize that stronghold, then in 977 Sabuktagin, his successor, became virtually independent and founded the dynasty of the Ghaznavids. Sabuktagin's son Mahmud of Ghazni had pushed further into the subcontinent, as far as east as modern day Agra. During his campaigns, many Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries had been looted and destroyed, as well as many people being forcibly converted into Islam. The primary motivation of his raids were the destruction and looting of Hindu temples, with examples being that of Somnath and the temples at Mathura.[15][16][unreliable source?]

Modern era

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin). In fact, this pun first appeared as a cartoon in Punch magazine. The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[17]

The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. Distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered time from time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[17]

The British desired to increase their profitability from Sindh and carried out extensive work on the irrigation system in Sindh, for example the Jamrao Canal project. However, the local Sindhis were described as both eager and lazy and for this reason the British authorities encouraged the immigration of Punjabi peasants into Sindh as they were deemed more hard-working. Punjabi migrations to Sindh paralleled the further development of Sindh’s irrigation system in the early 20th century. Sindhi apprehension of a ‘Punjabi invasion’ grew.[17]

In his backdrop, desire for a separate administrative status for Sindh grew. At the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1913, a Sindhi Hindu put forward the demand for Sindh’s separation from the Bombay Presidency on the grounds of Sindh’s unique cultural character. This reflected the desire of Sindh’s predominantly Hindu commercial class to free itself from competing with the more powerful Bombay’s business interests.[17] Meanwhile, Sindhi politics was characterised in the 1920s by the growing importance of Karachi and the Khilafat Movement.[18] A number of Sindhi pirs, descendants of Sufi saints who had proselytised in Sindh, joined the Khilafat Movement, which propagated the protection of the Ottoman Caliphate, and those pirs who did not join the movement found a decline in their following.[19] The pirs generated huge support for the Khilafat cause in Sindh.[20] Sindh came to be at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement.[21]

Although Sindh had a cleaner record of communal harmony than other parts of India, the province’s Muslim elite and emerging Muslim middle class demanded separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency as a safeguard for their own interests. In this campaign local Sindhi Muslims identified ‘Hindu’ with Bombay instead of Sindh. Sindhi Hindus were seen as representing the interests of Bombay instead of the majority of Sindhi Muslims. Sindhi Hindus, for the most part, opposed the separation of Sindh from Bombay.[17] Sindh’s Hindu and Muslim communities lived in close proximity to each other and extensively influenced each other’s culture. Scholars have discussed that it was found that Hindu practices in Sindh differed from orthodox Hinduism in the rest of India. Hinduism in Sindh was to a large extent influenced by Islam, Sikhism and Sufism. Sindh’s religious syncretism was a result of Sufism. Sufism was a vital component of Sindhi Muslim identity and Sindhi Hindus, more than Hindus in any other part of India, came under the influence of Sufi thought and practices and the majority of them were murids (followers) of Sufi Muslim saints.[22]

However, both the Muslim landed elite, waderas, and the Hindu commercial elements, banias, collaborated in oppressing the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Sindh who were economically exploited. In Sindh’s first provincial election after its separation from Bombay in 1936, economic interests were an essential factor of politics informed by religious and cultural issues.[23] Due to British policies, much land in Sindh was transferred from Muslim to Hindu hands over the decades.[24] The exploitation of Sindhi Muslims by Sindhi Hindus had reached alarming proportions.[25] Religious tensions rose in Sindh over the Sukkur Manzilgah issue where Muslims and Hindus disputed over an abandoned mosque in proximity to an area sacred to Hindus. The Sindh Muslim League exploited the issue and agitated for the return of the mosque to Muslims. Consequentially, a thousand members of the Muslim League were imprisoned. Eventually, due to panic the government restored the mosque to Muslims.[23]

The separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency triggered Sindhi Muslim nationalists to support the Pakistan Movement. Even while the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province were ruled by parties hostile to the Muslim League, Sindh remained loyal to Jinnah.[26] Although the prominent Sindhi Muslim nationalist G.M. Syed left the All India Muslim League in the mid-1940s and his relationship with Jinnah never improved, the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan, seeing in it their deliverance.[18] Sindhi support for the Pakistan Movement arose from the desire of the Sindhi Muslim business class to drive out their Hindu competitors.[27] The Muslims League’s rise to becoming the party with the strongest support in Sindh was in large part linked to its winning over of the religious pir families. Although the Muslim Leaue had previously fared poorly in the 1937 elections in Sindh, when local Sindhi Muslim parties won more seats,[28] the Muslim League’s cultivation of support from the pirs and saiyids of Sindh in 1946 helped it gain a foothold in the province.[29]

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.[30]

References

- ^ Singh, Mohinder. History and Culture of Panjab. Atlantic Publishers. p. 1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Singh, Mohinder. History and Culture of Panjab. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 2–3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Panikkar, K.M (1966). A Survey of Indian History. Asia Publishing House.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (2003). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts, and Historical Issues. Permanent Black Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 81-7824-143-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (2003). Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts, and Historical Issues. Permanent Black Publishers. pp. 56–57. ISBN 81-7824-143-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Thorpe, p. 33.

- ^ Chaurasia, p. 126.

- ^ Panikkar, p. 113.

- ^ Tandle, p. 269.

- ^ Tandle, p. 270.

- ^ Tandle, p. 270-271.

- ^ Kazi 1990, p. 8.

- ^ Panikkar, p. 113-114.

- ^ Panikkar, p. 114.

- ^ Panikkar, p. 115.

- ^ Wynbrandt, p. 52-55.

- ^ a b c d e Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4.

- ^ a b I. Malik (3 June 1999). Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0.

- ^ Gail Minault (1982). The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India. Columbia University Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-231-05072-2.

- ^ Sarah F. D. Ansari (31 January 1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

- ^ Pakistan Historical Society (2007). Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 245.

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 775, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ a b Ayesha Jalal (4 January 2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. pp. 415–. ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0.

- ^ Amritjit Singh; Nalini Iyer; Rahul K. Gairola (15 June 2016). Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics. Lexington Books. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4.

- ^ Muhammad Soaleh Korejo (1993). The Frontier Gandhi: His Place in History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-577461-0.

- ^ Khaled Ahmed (18 August 2016). Sleepwalking to Surrender: Dealing with Terrorism in Pakistan. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 230–. ISBN 978-93-86057-62-4.

- ^ Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

- ^ Sarah F. D. Ansari (31 January 1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

- ^ Sarah F. D. Ansari (31 January 1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 776-777, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

Sources

- "A Survey Of Indian History K. M. Panikkar". 15 August 1947.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - Tandle, S. Indian History. Lulu. ISBN 978-1-312-37211-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. New York: Infobase Publishing.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Thorpe, Showick; Thorpe, Edgar (2009). The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1/e. Pearson. ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9.

- Chaurasia, R.S. (2002). History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Limited. ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kazi, M.A. (1990). Journey Through Judiciary. Royal Book Company. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)