Qasem Soleimani

This article is being heavily edited because its subject has recently been confirmed to have died. Knowledge about the circumstances of the death and surrounding events may change rapidly as more facts come to light. Initial news reports may be unreliable, and the last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

Qasem Soleimani (Persian: قاسم سلیمانی, pronounced [ɢɒːseme solejmɒːniː]; 11 March 1957 – 3 January 2020), also spelled Qassem Suleimani or Qassim Soleimani, was an Iranian major general in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and, from 1998 until his death, commander of its Quds Force, a division primarily responsible for extraterritorial military and clandestine operations.

Soleimani began his military career in the beginning of the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s, during which he eventually commanded the 41st Division. He was later involved in extraterritorial operations, providing military assistance to Hezbollah in Lebanon. In 2012, Soleimani helped bolster the Syrian government, a key Iranian ally, during the Syrian Civil War, particularly in its operations against ISIL and its offshoots. Soleimani also assisted in the command of combined Iraqi government and Shia militia forces that advanced against ISIL in 2014–2015.

Soleimani was killed in a targeted U.S. drone strike on 3 January 2020 in Baghdad, Iraq. Also killed were Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces members and its deputy head, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.[19] Soleimani was succeeded as commander of the Quds Force by Esmail Ghaani.[20]

Early life

Soleimani was born on 11 March 1957 in the village of Qanat-e Malek, Kerman Province,[21] to an impoverished peasant family. In his youth, he moved to the city of Kerman and worked as a construction worker to help repay a debt his father owed. In 1975, he began working as a contractor for the Kerman Water Organization.[22][23] When not at work, he spent his time lifting weights in local gyms and attending the sermons of a traveling preacher, Hojjat Kamyab, a protege of Ayatollah Khomeini.[24]

Military career

Soleimani joined the Revolutionary war Guard (IRGC) in 1979 following the Iranian Revolution, which saw the Shah fall and Ayatollah Khomeini take power. Reportedly, his training was minimal, but he advanced rapidly. Early in his career as a guardsman, he was stationed in northwestern Iran, and participated in the suppression of a Kurdish separatist uprising in West Azerbaijan Province.[24]

I entered the [Iran-Iraq] war on a fifteen-day mission, and ended up staying until the end. … We were all young and wanted to serve the revolution.

— Qassem Soleimani, Quoted in Dexter Filkins (30 September 2013). "The Shadow Commander". The New Yorker.

On 22 September 1980, when Saddam Hussein launched an invasion of Iran, setting off the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), Soleimani joined the battlefield serving as the leader of a military company, consisting of men from Kerman whom he personally assembled and trained.[25] He quickly earned a reputation for bravery,[26] and rose through the ranks because of his role in the successful operations in retaking the lands Iraq had occupied, eventually becoming the commander of the 41st Sarallah Division while still in his 20s, participating in most major operations. He was mostly stationed at the southern front.[25][27] He was seriously injured in Operation Tariq-ol-Qods. In a 1990 interview, he mentioned Operation Fath-ol-Mobin as "the best" operation he participated in and "very memorable", due to its difficulties yet positive outcome.[28] He was also engaged in leading and organizing irregular warfare missions deep inside Iraq carried out by the Ramadan Headquarters. It was at this point that Suleimani established relations with Kurdish Iraqi leaders and the Shia Badr Organization, both of which were opposed to Iraq's Saddam Hussein.[25]

On 17 July 1985, Soleimani opposed the IRGC leadership’s plan to deploy forces to two islands in western Arvandroud (Shatt al-Arab).[29]

After the war, during the 1990s, he was an IRGC commander in Kerman Province.[27] In this region, which is relatively close to Afghanistan, Afghan-grown opium travels to Turkey and on to Europe. Soleimani's military experience helped him earn a reputation as a successful fighter against drug trafficking.[24]

During the 1999 student revolt in Tehran, Soleimani was one of the IRGC officers who signed a letter to President Mohammad Khatami. The letter stated that if Khatami did not crush the student rebellion the military would, and it might also launch a coup against Khatami.[24][30]

Command of Quds Force

The exact date of his appointment as commander of the IRGC's Quds Force is not clear, but Ali Alfoneh cites it as between 10 September 1997 and 21 March 1998.[23] He was considered one of the possible successors to the post of commander of the IRGC, when General Yahya Rahim Safavi left this post in 2007. In 2008, he led a group of Iranian investigators looking into the death of Imad Mughniyah. Soleimani helped arrange a ceasefire between the Iraqi Army and Mahdi Army in March 2008.[31]

Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, Ryan Crocker, a senior State Department official in the United States, flew to Geneva to meet with Iranian diplomats who were under the direction of Soleimani with the purpose of collaborating to destroy the Taliban, which had targeted Shia Afghanis.[24] This collaboration was instrumental in defining the targets of bombing operations in Afghanistan and in capturing key Al-Qaeda operatives, but abruptly ended in January 2002, when President George W. Bush named Iran as part of the "Axis of evil" in his State of the Union address.[24]

In 2009, a leaked report stated that General Soleimani met Christopher R. Hill and General Raymond T. Odierno (America's two most senior officials in Baghdad at the time) in the office of Iraq’s president, Jalal Talabani (who knew General Soleimani for decades). Hill and General Odierno denied the occurrence of the meeting.[32]

On 24 January 2011, Soleimani was promoted to Major General by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei.[27][33] Khamenei was described as having a close relationship with him, calling Soleimani a "living martyr" and helping him financially.[24]

Soleimani was described as "the single most powerful operative in the Middle East today" and the principal military strategist and tactician in Iran's effort to combat Western influence and promote the expansion of Shiite and Iranian influence throughout the Middle East.[24] In Iraq, as the commander of the Quds force, he was believed to have strongly influenced the organization of the Iraqi government, notably supporting the election of previous Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri Al-Maliki.[24][34] Soleimani has even been described as being "Iran’s very own Erwin Rommel".[35]

According to some sources, Soleimani was the principal leader and architect of the military wing of the Lebanese Shia party Hezbollah since his appointment as Quds commander in 1998.[24] In an interview aired in October 2019, he said he was in Lebanon during the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war to oversee the conflict.[36]

Syrian Civil War

According to several sources, including Riad Hijab, a former Syrian premier who defected in August 2012, he was also one of the staunchest supporters of the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian Civil War.[24][34] In the later half of 2012, Soleimani assumed personal control of the Iranian intervention in the Syrian Civil War, when Iranians became deeply concerned about the Assad government's lack of ability to fight the opposition, and the fallout to the Islamic Republic if the Syrian government fell. He was reported to have coordinated the war from a base in Damascus at which a Lebanese Hezbollah commander and an Iraqi Shiite militia coordinator have been mobilized, in addition to Syrian and Iranian officers. Brigadier General Hossein Hamadani, the Basij’s former deputy commander, helped to run irregular militias that Soleimani hoped to continue the fight if Assad fell.[24] Under Soleimani the command "coordinated attacks, trained militias, and set up an elaborate system to monitor rebel communications". In an article for The New Yorker, Dexter Filkins said that thousands of Quds Force and Iraqi Shiite militiamen in Syria were "spread out across the entire country”[24] and that Soleimani orchestrated the The Battle of al-Qusayr of Qusayr afer it was captured by rebels.[37]

Soleimani was much credited in Syria for the strategy that assisted President Bashar al-Assad in finally repulsing rebel forces and recapture key cities and towns.[38] He was involved in the training of government-allied militias and the coordination of decisive military offensives.[24] The sighting of Iranian UAVs in Syria strongly suggested that his command, the Quds force, was involved in the civil war.[24] In a visit to the Lebanese capital Beirut on Thursday 29 January 2015, Soleimani laid wreaths at the graves of the slain Hezbollah members, including Jihad Mughniyah, the son of late Hezbollah commander Imad Mughniyah which strengthens some possibilities about his role in Hezbollah military reaction on Israel.[39]

Soleimani helped form of the National Defence Forces (NDF) in Syria.[40]

In October 2015, it was reported that he had been instrumental in devising during his visit to Moscow in July 2015 the Russian–Iranian–Syrian offensive in October 2015.[41]

War on ISIS in Iraq

Qasem Soleimani was in the Iraqi city of Amirli, to work with the Iraqi forces to push back militants from ISIL.[43][44] According to the Los Angeles Times, which reported that Amerli was the first town to successfully withstand an ISIS invasion, it was secured thanks to "an unusual partnership of Iraqi and Kurdish soldiers, Iranian-backed Shiite militias and U.S. warplanes". The US acted as a force multiplier for a number of Iranian-backed armed groups—at the same time that was present on the battlefield.[45][46]

A senior Iraqi official told the BBC that when the city of Mosul fell, the rapid reaction of Iran, rather than American bombing, was what prevented a more widespread collapse.[10] Qasem Soleimani also seems to have been instrumental in planning the operation to relieve Amirli in Saladin Governorate, where ISIL had laid siege to an important city.[42] In fact the Quds force operatives under Soleimani's command seem to have been deeply involved with not only the Iraqi army and Shi'ite militias but also the Kurdish in the battle of Amirli,[47] not only providing liaisons for intelligence sharing but also the supply of arms and munitions in addition to "providing expertise".[48]

In the operation to liberate Jurf Al Sakhar, he was reportedly "present on the battlefield". Some Shia militia commanders described Soleimani as "fearless"—one pointing out that the Iranian general never wears a flak jacket, even on the front lines.[49]

Hadi al-Amiri, the former Iraqi minister of transportation and the head of the Badr Organization [an official Iraqi political party whose military wing is one of the largest armed forces in the country] highlighted the pivotal role of General Qasem Soleimani in defending Iraq's Kurdistan Region against the ISIL terrorist group, maintaining that if it were not for Iran, Heidar al-Ebadi's government would have been a government-in-exile right now[52] and he added there would be no Iraq if Gen. Soleimani hadn't helped us.[53]

There were reports by some Western sources that Soleimani was seriously wounded in action against ISIL in Samarra. The claim was rejected by Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister for Arab and African Affairs Hossein Amir-Abdollahian.[54]

Soleimani played an integral role in the organisation and planning of the crucial operation to retake the city of Tikrit in Iraq from ISIS. The city of Tikrit rests on the left bank of the Tigris river and is the largest and most important city between Baghdad and Mosul, gifting it a high strategic value. The city fell to ISIS during 2014 when ISIS made immense gains in northern and central Iraq. After its capture, ISIL's massacre at Camp Speicher led to 1,600 to 1,700 deaths of Iraqi Army cadets and soldiers. After months of careful preparation and intelligence gathering an offensive to encircle and capture Tikrit was launched in early March 2015.[51] Soleimani was directing the operations on the eastern flank from a village about 35 miles from Tikrit called Albu Rayash, captured over the weekend.[citation needed] The offensive was the biggest military operation in the Salahuddin region since the previous summer, when ISIS fighters killed hundreds of Iraq army soldiers who had abandoned their military base at Camp Speicher outside Tikrit.[citation needed]

Orchestration of military escalation in 2015

In 2015 Soleimani started to gather support from various sources in order to combat the newly resurgent ISIL and rebel groups which were both successful in taking large swathes of territory away from Assad's forces. He was reportedly the main architect of the joint intervention involving Russia as a new partner with Assad and Hezbollah.[55][56][57]

According to Reuters, at a meeting in Moscow in July, Soleimani unfurled a map of Syria to explain to his Russian hosts how a series of defeats for President Bashar al-Assad could be turned into victory—with Russia's help. Qasem Soleimani's visit to Moscow was the first step in planning for a Russian military intervention that has reshaped the Syrian war and forged a new Iranian–Russian alliance in support of the Syrian (and Iraqi) governments. Iran's supreme leader, Ali Khamenei also sent a senior envoy to Moscow to meet President Vladimir Putin. "Putin reportedly told the envoy 'Okay we will intervene. Send Qassem Soleimani'. General Soleimani went to explain the map of the theatre and coordinate the strategic escalation of military forces in Syria.[56]

Operations in Aleppo

Soleimani had a decisive impact on the theatre of operations and led to a strong advance in southern Aleppo with the government and allied forces re-capturing two military bases and dozens of towns and villages in a matter of weeks. There was also a series of major advances towards Kuweiris air-base to the north-east.[64] By mid-November, the Syrian army and its allies had gained ground in southern areas of Aleppo Governorate, capturing numerous rebel strongholds. Soleimani was reported to have personally led the drive deep into the southern Aleppo countryside where many towns and villages fell into government hands. He reportedly commanded the Syrian Arab Army’s 4th Mechanized Division, Hezbollah, Harakat Al-Nujaba (Iraqi), Kata'ib Hezbollah (Iraqi), Liwaa Abu Fadl Al-Abbas (Iraqi), and Firqa Fatayyemoun (Afghan/Iranian volunteers).[65]

Soleimani was lightly wounded while fighting in Syria, outside of Al-Eis. Reports initially speculated that he was seriously or gravely injured.[66] He was quoted as saying, "Martyrdom is what I seek in mountains and valleys, but it isn't granted yet".[67]

In early February 2016, backed by Russian and Syrian air force airstrikes, the 4th Mechanized Division – in close coordination with Hezbollah, the National Defense Forces (NDF), Kata'eb Hezbollah, and Harakat Al-Nujaba – launched an offensive in Aleppo Governorate's northern countryside,[68] which eventually broke the three-year siege of Nubl and Al-Zahraa and cut off rebel's main supply route from Turkey. According to a senior, non-Syrian security source close to Damascus, Iranian fighters played a crucial role in the conflict. "Qassem Soleimani is there in the same area", he said.[69] In December 2016, new photos emerged of Soleimani at the Citadel of Aleppo, though the exact date of the photos is unknown.[70][71]

Operations in 2016 and 2017

In 2016, photos published by a Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) source showed Iran's Quds Force commander Qassem Suleimani and other PMF commanders discussing the Battle of Fallujah.[72]

In late March 2017, Soleimani was seen in the northern Hama Governorate countryside, reportedly aiding Maj. Gen. Suheil al-Hassan in repelling a major rebel offensive.[16]

CIA chief Mike Pompeo said that he sent Soleimani and other Iranian leaders a letter holding them responsible for any attacks on US interests by forces under their control. According to Mohammad Mohammadi Golpayegani, a senior aide for Iran's supreme leader, Soleimani ignored the letter when it was handed over to him during the Abu Kamal offensive against ISIL, saying "I will not take your letter nor read it and I have nothing to say to these people."[73][74]

In politics

In 1999, Soleimani, along with other senior IRGC commanders, signed a letter to then-President Mohammad Khatami regarding the student protests in July. They wrote "Dear Mr. Khatami, how long do we have to shed tears, sorrow over the events, practice democracy by chaos and insults, and have revolutionary patience at the expense of sabotaging the system? Dear president, if you don't make a revolutionary decision and act according to your Islamic and national missions, tomorrow will be so late and irrecoverable that cannot be even imagined."[75]

Iranian media reported in 2012 that he might be replaced as the commander of Quds Force in order to allow him to run in the 2013 presidential election.[76] He reportedly refused to be nominated for the election.[75] According to BBC News, in 2015 a campaign started among conservative bloggers for Soleimani to stand for 2017 presidential election.[77] In 2016, he was speculated as a possible candidate,[75][78] however in a statement published on 15 September 2016, he called speculations about his candidacy as "divisive reports by the enemies" and said he will "always remain a simple soldier serving Iran and the Islamic Revolution".[79]

In the summer of 2018, Soleimani and Tehran exchanged public remarks related to Red Sea shipping with American President Donald Trump which heightened tensions between the two countries and their allies in the region.[80]

Personal life

Soleimani was a Persian from Kerman. His father was a farmer who died in 2017. His mother, Fatemeh, died in 2013.[81] He came from a family of nine and had five sisters and one brother, Sohrab, who lived and worked with Soleimani in his youth.[82] Sohrab Soleimani is a warden and former director general of the Tehran Prisons Organization. The United States imposed sanctions on Sohrab Soleimani in April 2017 "for his role in abuses in Iranian prisons".[83]

Soleimani had dan in karate and was a fitness trainer in his youth. He had four children: two sons and two daughters.[84]

Sanctions

In March 2007, Soleimani was included on a list of Iranian individuals targeted with sanctions in United Nations Security Council Resolution 1747.[85] On 18 May 2011, he was sanctioned again by the United States along with Syrian president Bashar al-Assad and other senior Syrian officials due to his alleged involvement in providing material support to the Syrian government.[86]

On 24 June 2011, the Official Journal of the European Union said the three Iranian Revolutionary Guard members now subject to sanctions had been "providing equipment and support to help the Syrian government suppress protests in Syria".[87] The Iranians added to the EU sanctions list were two Revolutionary Guard commanders, Soleimani, Mohammad Ali Jafari, and the Guard's deputy commander for intelligence, Hossein Taeb.[88] Soleimani was also sanctioned by the Swiss government in September 2011 due to the same grounds cited by the European Union.[89]

He was listed by the United States as a known terrorist, which forbade U.S. citizens from doing business with him.[31][90] The list, published in the EU's Official Journal on 24 June 2011, also included a Syrian property firm, an investment fund and two other enterprises accused of funding the Syrian government. The list also included Mohammad Ali Jafari and Hossein Taeb.[91]

On 13 November 2018, the United States sanctioned an Iraqi military leader named Shibl Muhsin ‘Ubayd Al-Zaydi and others who allegedly were acting on Qasem Soleimani's behalf in financing military actions in Syria or otherwise providing support for terrorism in the region.[92]

Death

Soleimani was killed on 3 January 2020 around 1 am local time (22:00 UTC on 2 January)[93], after missiles shot from American drones targeted his convoy near Baghdad International Airport.[94] He had just left his plane, which arrived in Iraq from Lebanon or Syria.[95] His body was identified using a ring he wore on his finger, with DNA confirmation still pending.[96] Also killed were four members of the Popular Mobilization Forces, including Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the Iraqi-Iranian military commander who headed the PMF.[97]

The airstrike followed attacks on the American embassy in Baghdad by supporters of an Iran-backed Iraqi Shia militia and the 2019 K-1 Air Base attack.[98]

The United States Department of Defense issued a statement that said the U.S. strike was carried out "at the direction of the President" and asserted that Soleimani had been planning further attacks on American diplomats and military personnel and had approved the attacks on the American embassy in Baghdad in response to U.S. airstrikes in Iraq and Syria on 29 December 2019, and that the strike was meant to deter future attacks.[99][100]

He was succeeded by Esmail Ghaani as commander of the Quds Force.[20]

Cultural depictions

He was described as having "a calm presence",[101] and as carrying himself "inconspicuously and rarely rais[ing] his voice", exhibiting "understated charisma".[26] In Western sources, Suleimani's personality was compared to the fictional characters Karla, Keyser Söze,[26] and The Scarlet Pimpernel.[102]

Unlike other IRGC commanders, he usually did not appear in his official military clothing, even in the battlefield.[103][104]

In January 2015, Hadi Al-Ameri the head of the Badr Organization in Iraq said of him: "If Qasem Soleimani were not present in Iraq, Haider al-Abadi would not be able to form his cabinet within Iraq".[105]

The British magazine The Week featured a cartoon Soleimani of in bed with Uncle Sam in 2015, which indicated to both sides fighting ISIS, although Soleimani was leading militant groups that killed hundreds of Americans during the Iraq War.[106]

The 2016 movie Bodyguard, directed by Ebrahim Hatamikia, was inspired by Soleimani's activities.[107]

The 2016 Persian book Noble Comrades 17: Hajj Qassem, written by Ali Akbari Mozdabadi, contains memoirs of Qassem Soleimani.[108]

Gallery

-

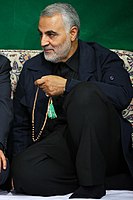

in Hussainiya

-

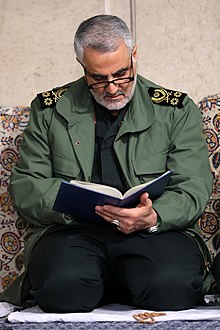

While praying

-

Soleimani with Ali Khamenei.

-

Soleimani in the NAC conference.

See also

- List of Iranian two-star generals since 1979

- Hossein Salami

- Mohammad Bagheri (Iranian commander)

- Iran–Saudi Arabia proxy conflict

- Iran–United States relations

References

- ^ "Qassem Suleimani not Just a Commander! – Taking a Closer Look at Religious Character of Iranian General". abna24. 10 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Dexter Filkins (30 September 2013). "The Shadow Commander". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Joanna Paraszczuk (16 October 2014). "Iran's 'Shadow Commander' Steps Into the Light". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Kambiz Foroohar. "Iran's Shadow Commander". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "RealClearWorld - Syria's Iranian Shadow Commander". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Iran's 'shadow commander' steps into the spotlight". The Observers. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Qasem Soleimani among those killed in Baghdad Airport attack – report". Reuters. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "لشکر 41 ثارالله (ع) | دفاعمقدس". defamoghaddas.ir. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "عملیاتی که در آن سردار سلیمانی شدیداً مجروح شد". yjc.ir. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ a b "El iraní Qasem Soleimani, "el hombre más poderoso en Irak"". Terra. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ soleimani reveals details role he played 2006 israel hezbollah war Archived 24 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine aawsat.com

- ^ Shadowy Iran commander Qassem Soleimani gives rare interview on 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war Archived 24 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine thenational.ae

- ^ "Pictures reportedly place Iranian general in Daraa". Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Iran's Revolutionary Guards executes 12 Assad's forces elements". Iraqi News. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Hermann, Rainer (15 October 2016). "Die Völkerschlacht von Aleppo". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ a b Amir Toumaj (2 April 2017). "Qassem Soleimani reportedly spotted in Syria's Hama province". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ^ "Leader awards General Soleimani with Iran's highest military order". Press TV. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "عکس/ مدال های فرمانده نیروی قدس سپاه". Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ CNN, Zachary Cohen, Hamdi Alkhshali, Arwa Damon and Kareem Khadder. "US drone strike ordered by Trump kills top Iranian commander in Baghdad". CNN. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Soleimani's Deputy Esmail Ghaani Named Iran's Quds Force Chief". Bloomberg. 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Iran Guards Intelligence Chief Says Plot To Kill Soleimani Neutralized". Radio Farda. 3 October 2019. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ O'Hern, Steven (31 October 2012). Iran's Revolutionary Guard: The Threat That Grows While America Sleeps. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-59797-701-2.

- ^ a b Alfoneh, Ali (January 2011). "Brigadier General Qassem Suleimani: A Biography" (PDF). Middle Eastern Outlooks. 1: 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Filkins, Dexter (30 September 2013). "The Shadow Commander". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b c "The enigma of Qasem Soleimani and his role in Iraq". Al Monitor. 13 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Weiss, Michael (2 July 2014). "Iran's Top Spy Is the Modern-Day Karla, John Le Carré's Villainous Mastermind". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ a b c Alfoneh, Ali (March 2011). "Iran's Secret Network: Major General Qassem Suleimani's Inner Circle" (PDF). Middle Eastern Outlooks. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "بخشهای خواندنی کتاب "حاج قاسم"". yjc.ir. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "News & Views". The Iranian. July 1999. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Iranian who brokered Iraqi peace is on U.S. terrorist watch list". McClatchy Newspapers. 31 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 July 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ Iraq and its neighbours: A regional cockpit Archived 24 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Economist

- ^ "The Islamic Republic's 13 generals". Iran Briefing. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ a b Abbas, Mushreq (12 March 2013). "Iran's Man in Iraq and Syria". Al Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ Bret Stephens (16 March 2015). "Bret Stephens: What Assad Knows – WSJ". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Soleimani: Mastermind of Iran's Expansion". The Iran Primer. 14 October 2019.

- ^ Filkins, Dexter (23 September 2013). "The Shadow Commander". New Yorker. New Yorker.

A turning point came in April, after rebels captured the Syrian town of Qusayr, near the Lebanese border. To retake the town, Suleimani called on Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah's leader, to send in more than two thousand fighters...On June 5th, the town fell. "The whole operation was orchestrated by Suleimani," Maguire, who is still active in the region, said.

- ^ "Iran's Qasem Soleimani wields power behind the scenes in Iraq". BBC News. 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Iran's Soleimani pays tribute to fallen Hezbollah fighters". Mehr News. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ Merat, Arron (10 October 2019). "In an attack on Iran, misunderstanding Qasim Soleimani could be America's downfall". Prospect. Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "How Iranian general plotted out Syrian assault in Moscow". Reuters. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Suleimani was present during battle for Amerli". Business Insider. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ^ "Iraqi and Kurdish troops enter the sieged Amirli". BBC News. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 August 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "So hilft Israels Todfeind den USA im Kampf gegen ISIS!". Bild. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ Bengali, Shashank (2 September 2014). "In Iraq, residents of Amerli celebrate end of militant siege". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ "Soleimani: Iran to help Iraq as needed". Tehran Times. 28 May 2016. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Ahmed, Azam (3 September 2014). "Waging Desperate Campaign, Iraqi Town Held Off Militants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Iranians play role in breaking ISIS siege of Iraqi town". Reuters. 1 September 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Abdul-Zahra, Qassim; Salama, Vivian (5 November 2014). "Iran general said to mastermind Iraq ground war". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ "Iranian General Again in Iraq for Tikrit Offensive". defensenews.com. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ a b Rasheed, Ahmad (3 March 2015). "Iraqi army and militias surround Isis in major offensive in the battle for Tikrit". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ "Iraq owes many victories against ISIL to Iran". MehrNews. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "هادي العامري: لولا ايران وسليماني لما كانت الحكومة العراقية موجودة في بغداد". وكالة مهر للانباء. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Major General Soleimani not injured: Iran". Press TV. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "Iranian General Attended Moscow Meeting To Plan Syrian Assault". Headlines & Global News. 7 October 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ a b "How Iranian general plotted out Syrian assault in Moscow". Reuters. 6 October 2015. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Thiessen, Marc A. (7 October 2015). "How an Iranian terrorist plotted Russia's Syria intervention". American Enterprise Institute. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Syrian Army Captures Al-Nasiriyah in East Aleppo: 7km from Kuweires Military Airport". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Syrian Army and Hezbollah Capture 25km of Territory in Southern Aleppo While the Islamists Counter". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Syrian Army and Hezbollah Continue to Roll in Southern Aleppo: Several Sites Captured". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Cheetah Forces Press Further in East Aleppo: Hilltops Overlooking Tal Sab'een Captured". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Cheetah Forces Capture Tal Sab'een Amid Russian Airstrikes in East Aleppo". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 22 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Hezbollah and the Syrian Army Seize Several Sites in Southern Aleppo". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ Alami, Mona (23 October 2015). "What the Aleppo offensive hides". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ Leith Fadel. "Where is Major General Qassem Suleimani?". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Iran general Soleimani lightly wounded in Syria". Yahoo News. 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ اﻟﺘﺤﻟﻴﻟﻲ, موقع الوقت (30 November 2015). "Alwaght Exclusive: Qasem Soleimani Talks about Rokn Abadi and Himselfs Death Rumors". الوقت. Archived from the original on 4 December 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ Syrian Army, Hezbollah launch preliminary offensive in northern Aleppo Archived 31 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine almasdarnews.com

- ^ "Russia and Turkey trade accusations over Syria". 5 February 2016. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Reuters.

- ^ Toumaj, Amir (18 December 2016). "IRGC Qods Force chief spotted in Aleppo". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016.

On Friday, photos emerged of Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Qods Force, in conquered eastern Aleppo, Syria (photos 1, 2). Another photo showed him by the Citadel of Aleppo (photo 3). It was not immediately clear when the photos were taken.

- ^ "Syria: Iran's General Soleimani in Aleppo". Fars News Agency. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016.

New photos show the Commander of the Quds Force of Iran's Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) Major General Qassem Soleimani at the Citadel of Aleppo after its liberation as Syria is preparing to celebrate its victory in the crucially important city

- ^ "Iran's Gen. Soleimani in Fallujah Operations Room". Fars News. Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ^ "CIA chief Pompeo says he warned Iran's Soleimani over Iraq aggression". Reuters. 2017. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ "CIA director sent warning to Iran over threatened US interests in Iraq". The Guardian. Associated Press. 3 December 2017. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Nozhan Etezadosaltaneh (16 May 2016), "Will Qasem Soleimani Become the Next President of Iran?", International Policy Digest, archived from the original on 15 April 2017, retrieved 1 January 2017

- ^ Iran's Conservatives Grapple for Power, Stratfor, 1 March 2012, archived from the original on 10 October 2017, retrieved 1 January 2017

- ^ Bozorgmehr Sharafedin (6 March 2015), General Qasem Soleimani: Iran's rising star, BBC News, archived from the original on 27 December 2016, retrieved 1 January 2017

- ^ Akbar Ganji (13 May 2015), "Iran's Hardliners Might Be Making a Comeback -- And the West Should Pay Attention", Huffington Post, archived from the original on 29 February 2016, retrieved 1 January 2016

- ^ Who will be Iran's next president?, The Iran Project, 29 September 2016, archived from the original on 4 January 2017, retrieved 1 January 2017

- ^ Cunningham, Erin; Fahim, Kareem (26 July 2018). "Top Iranian general warns Trump that war would unravel U.S. power in region". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ "مادر حاج قاسم سلیمانی درگذشت". 18 June 1392. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "پاسخ پرمعنای پدر سردار قاسم سلیمانی به استاندار". Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ "U.S. sanctions brother of Iran's Quds force commander: White House". Reuters. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ "خبرگزاری فارس - رازهای زندگی سردار ایرانی/ حاج قاسم چگونه زندگی میکند". خبرگزاری فارس. 24 August 2015. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "United Nations Security Council Resolution 1747" (PDF). United Nations. 24 March 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ Alfoneh, Ali (July 2011). "Iran's Most Dangerous General" (PDF). Middle Eastern Outlooks. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 611/2011 of 23 June 2011". Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Syria: Deadly protests erupt against Bashar al-Assad". BBC News. 24 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Ordinance instituting measures against Syria" (PDF). Federal Department of Economy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "Designation of Iranian Entities and Individuals for Proliferation Activities and Support for Terrorism". United States Department of State. 25 October 2007. Archived from the original on 4 February 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ "EU expands sanctions against Syria". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 24 October 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ United States Department of Treasury. (Press release 13 November 2018). "Action follows signing of new Hizballah sanctions legislation and re-imposition of Iran-related sanctions". US. Dept of Treasury website Archived 17 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Ghattas, Kim (3 January 2020). "Qassem Soleimani Haunted the Arab World". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Tom O'Connor; James Laporta. "Iraq Militia Officials, Iran's Quds Force Head Killed in U.S. Drone Strike". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "US kills Iran's most powerful general in Baghdad airstrike". AP News. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Barbara Campbell (2 January 2020). "Iraqi TV Says Top Iranian Military Leader Killed In Rocket Strikes on Iraqi Airport". NPR. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Trump Orders Strike Killing Top Iranian General Qassim Suleimani in Baghdad". The New York Times. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Top Iranian general killed in US airstrike in Baghdad, Pentagon confirms". CNBC. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Statement by the Department of Defense". United States Department of Defense. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Iran general Qassem Suleimani killed in Baghdad drone strike ordered by Trump". The Guardian. 3 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Gorman, Jay Solomon And Siobhan (6 April 2012). "Iran's Spymaster Counters U.S. Moves in the Mideast". Archived from the original on 7 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Black, Ian; Dehghan, Saeed Kamali (16 June 2014). "Qassem Suleimani: commander of Quds force, puppeteer of the Middle East". Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ "Subscribe to read". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ Azodi, Sina. "Qasem Soleimani, Iran's Celebrity Warlord". Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "هادي العامري: لولا ايران وسليماني لما كانت الحكومة العراقية موجودة في بغداد". Mehr News Agency. 5 January 2015. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "The war on ISIS is getting weird in Iraq". Business Insider. 25 March 2015.

- ^ Peterson, Scott (15 February 2016). "Gen. Soleimani: A new brand of Iranian hero for nationalist times". Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016 – via Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "یاران ناب 17 : حاج قاسم : جستاری در | خرید کتاب یاران ناب 17 : حاج قاسم : جستاری در | فروشگاه کتاب کتابخون". ketabkhon.ir. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

External links

- David Ignatius, At the Tip of Iran's Spear, Washington Post, 8 June 2008

- Martin Chulov, Qassem Suleimani: the Iranian general 'secretly running' Iraq, The Guardian, 28 July 2011

- Dexter Filkins, The Shadow Commander, The New Yorker, 30 September 2013

- Ali Mamouri, The Enigma of Qasem Soleimani And His Role in Iraq, Al-Monitor, 13 October 2013

- BBC Radio 4 Profile

- Recent deaths

- 1957 births

- 2020 deaths

- Deaths by American airstrikes

- Persian people

- People from Kerman Province

- Recipients of the Order of Fath

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Major generals

- Iranian Shia Muslims

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps personnel of the Iran–Iraq War

- Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps personnel of the Syrian Civil War

- Quds Force personnel

- Assassinations in Iraq

- Criticism of the United States

- People of the Iraqi Civil War

- Assassinated Iranian people