Jabba the Hutt

| Jabba the Hutt | |

|---|---|

| Star Wars character | |

Jabba as he appears in Return of the Jedi (1983) | |

| First appearance |

|

| Last appearance | The Clone Wars |

| Created by | George Lucas |

| Portrayed by | Declan Mulholland (Episode IV; deleted scene, later restored and overlapped with CGI for 1997 Special Edition and subsequent releases) David Barclay/Toby Philpott/Mike Edmonds (puppeteers in Episode VI) Jackson |

| Voiced by | Larry Ward (Return of the Jedi) Ed Asner (Return of the Jedi radio drama) Randy Thornton (read-along storybook CDs) Unknown actor (Star Wars post-1997 versions and Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace) Clint Bajakian (Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (video game), Star Wars: Demolition, Star Wars: Galactic Battlegrounds, Star Wars: Bounty Hunter) Kevin Michael Richardson (Star Wars: The Clone Wars film and TV series, and Disney Infinity 3.0) David W. Collins (Star Wars: The Force Unleashed) Michael Donovan (Lego Star Wars: The Yoda Chronicles) |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Jabba Desilijic Tiure |

| Gender | Male (asexual; hermaphroditic) |

| Occupation | Crime lord |

| Family |

|

| Children | Rotta the Hutt (son) |

| Homeworld | Nal Hutta |

Jabba Desilijic Tiure,[1] (colloquial: Jabba the Hutt) is a fictional character in the Star Wars franchise created by George Lucas. He is a large, slug-like[2] alien known as a Hutt who, like many others of his species, operates as a powerful crime lord within the galaxy. He is notable for never speaking Basic, the main characters' language, though able to understand it, always replying in the constructed language Huttese.

In the original theatrical releases of the original Star Wars trilogy, Jabba the Hutt first appeared in Return of the Jedi (1983). However, he is mentioned in Star Wars (1977), The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and, indirectly, in Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018), while a previously deleted scene involving Jabba the Hutt was added to the 1997 theatrical re-release and subsequent home media releases of Star Wars. When first shot, this scene featured Declan Mulholland as a humanoid version of Jabba speaking the main character's language, which was digitally superimposed over with the character's monstrous current design when the footage was reincorporated into the film. In Star Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Menace (1999), Jabba appears in a sequence recreated in CGI.

In the storyline context of the original trilogy, Jabba is introduced as the most powerful crime boss on Tatooine, who has placed a bounty on the head of heroic smuggler Han Solo and employs bounty hunters such as Greedo and Boba Fett to capture or kill him. When confronted at his home palace after managing to capture Solo, Jabba is seen surrounded by a large host of extraterrestrial acquaintances, such as various fellow criminals, entertainers such as the Max Rebo Band, and slave girls, one of which Princess Leia is briefly made before ultimately killing her captor in the midst of a climactic battle sequence. Jabba is portrayed as a cruel antagonist with a grim sense of humor, an insatiable appetite (as is typical of his species), and affinities for torture and other heinous activities.[1]

The character has incorporated prominently into Star Wars merchandising beginning with the marketing campaign corresponding with the theatrical release of Return of the Jedi. Besides the canonical films, Jabba the Hutt is additionally featured in various pieces of Star Wars Legends literature. Since his appearance in Return of the Jedi, Jabba the Hutt's image has been highly influential and recognizable in contemporary popular culture, commonly being used as a satirical literary device and/or political caricature to underscore negative qualities such as morbid obesity and corruption.[3][4]

Appearances

Jabba the Hutt appears in three of the nine live-action Star Wars films (The Phantom Menace, A New Hope and Return of the Jedi) and The Clone Wars. He has a recurring role in Star Wars expanded universe literature and stars in the comic book anthology Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal (1998), a collection of comics originally published in 1995 and 1996.

Star Wars films

Jabba was first seen in 1983 in Return of the Jedi, the third installment of the original Star Wars trilogy. Directed by Richard Marquand and written by Lawrence Kasdan and George Lucas, the first act of Return of the Jedi features the attempts of Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher), the Wookiee Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew), and Jedi Knight Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) to rescue their friend, Han Solo (Harrison Ford), who had been imprisoned in carbonite in the previous film, The Empire Strikes Back.[5]

The captured Han is delivered to Jabba by the bounty hunter Boba Fett (Jeremy Bulloch) and placed on display in the crime lord's throne room as a decoration. Lando Calrissian (Billy Dee Williams), droids C-3PO (Anthony Daniels) and R2-D2 (Kenny Baker), Leia, and Chewbacca infiltrate Jabba's palace to save Han. Leia is able to free Han from the carbonite, but she is caught and enslaved by the Hutt. Chained to Jabba, she is forced to wear her iconic metal bikini. Luke arrives to "bargain for Solo's life", but Jabba rejects his offer and attempts to feed him to his pet rancor, an enormous monster. Luke kills the rancor, and he, Han, and Chewbacca are condemned to be devoured by the Sarlacc. At the Great Pit of Carkoon, Luke escapes execution with the help of R2-D2, and defeats Jabba's guards. During the subsequent confusion, Leia chokes Jabba to death with the chain she was tethered to his throne with. Luke, Leia, Han, Lando, Chewbacca, C-3PO, and R2-D2 escape, and Jabba's sail barge explodes over the Sarlacc pit in the background.[5]

The second film appearance of Jabba the Hutt was in the Special Edition of Star Wars,[a] which was released in 1997 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of its release. Here (as in the original version), Han Solo disputes with the alien bounty hunter Greedo (Paul Blake and Maria De Aragon), whom he kills, and Jabba confirms Greedo's last words and demands that Han pay the value of the payload lost by him. Han promises to compensate Jabba as soon as he receives payment for delivering Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness), Luke Skywalker, R2-D2, and C-3PO to Alderaan. Jabba agrees, but threatens to place a big price on Solo's head if he fails. This was an unfinished scene of the original 1977 film, in which Jabba was played by Declan Mulholland in human form. In the 1997 Special Edition version of the film, a CGI rendering of Jabba replaces Mulholland, and his voice is redubbed in the fictional language of Huttese.[6]

Jabba the Hutt made his third film appearance in the 1999 prequel, Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace, set 36 years before Return of the Jedi. Jabba gives the order to begin a podrace at Mos Espa on Tatooine. With this done, Jabba falls asleep, and misses the race's conclusion.[7][8]

Jabba is mentioned in the film Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018) by Han Solo's mentor Tobias Beckett, who invites Han to join a big shot gangster for putting together a crew. At the end of the movie, Han and Chewie decide to go to Tatooine for this job.

The Clone Wars

Jabba figures into the plot of the animated film Star Wars: The Clone Wars, wherein his son Rotta is captured by Separatists; Jedi Knight Anakin Skywalker (voiced by Matt Lanter) and his Padawan Ahsoka Tano (voiced by Ashley Eckstein) return him to Jabba in exchange for the safe passage of Republic ships through his territory.

Jabba subsequently appeared in a handful of episodes of The Clone Wars series, starting in the third season. In the episode "Sphere of Influence", wherein Jabba is faced by Chairman Papanoida, whose daughters were kidnapped by Greedo, Jabba allows a sample of Greedo's blood to be taken to prove him the kidnapper. In the episode "Evil Plans", Jabba hires the bounty hunter Cad Bane (voiced by Corey Burton) to bring him plans for the Senate building. When Bane returns successful, Jabba and the Hutt Council send Bane to free Jabba's uncle Ziro from prison. Jabba next makes a short appearance in the episode "Hunt for Ziro" in which he is seen laughing at his uncle's death at the hand of Sy Snootles (voiced by Nika Futterman), and pays her for delivering Ziro's holo-diary. In the fifth season episode "Eminence", Jabba and the Hutt Council are approached by Shadow Collective leaders Darth Maul (voiced by Sam Witwer), Savage Opress (voiced by Clancy Brown), and Pre Vizsla (voiced by Jon Favreau); when disappointed by these, Jabba sends bounty hunters Embo (voiced by Dave Filoni), Dengar (voiced by Simon Pegg), Sugi (voiced by Anna Graves), and Latts Razzi (voiced by Clare Grant) to capture them. After a battle, the Shadow Collective confront Jabba at his palace on Tatooine, where Jabba agrees to an alliance.

Other appearances

Expanded Universe

The first released appearances of Jabba the Hutt in any visual capacity were in Marvel Comics' adaptation of A New Hope. In Six Against the Galaxy (1977) by Roy Thomas, What Ever Happened to Jabba the Hut? (1979) and In Mortal Combat (1980), both by Archie Goodwin, Jabba the Hutt (originally spelled Hut) appeared as a tall humanoid with a walrus-like face, a topknot, and a bright uniform. The official "Jabba" was not yet established as he had yet to be seen.

While awaiting the sequel to Star Wars, Marvel kept the monthly comic going with their own stories, one of which includes Jabba tracking Han Solo and Chewbacca down to an old hideaway they use for smuggling. However, circumstances force Jabba to lift the bounty on Solo and Chewbacca, thus enabling them to return to Tatooine for an adventure with Luke Skywalker—who has returned to the planet in order to recruit more pilots for the Rebel Alliance. In the course of another adventure, Solo kills the space pirate Crimson Jack and busts up his operation, which Jabba bankrolled. Jabba thus renews the reward for Solo's head. Solo later kills a bounty hunter who tells him why he is hunted once more. He and Chewbacca return to the Rebels. (Solo mentions an incident with a "bounty hunter we ran into on Ord Mantell" in The Empire Strikes Back.)

The Marvel artists based this Jabba on a character later named Mosep Binneed, an alien visible only briefly in the Mos Eisley Cantina scene of A New Hope.[9][10][11][12] The 1977 mass-market paperback novelization of Lucas's Star Wars script describes Jabba as a "great mobile tub of muscle and suet topped by a shaggy scarred skull", but gives no further detail as to the character's physical appearance or species.[13]

Later Star Wars novels and comics adopt a version of the character's image as seen in the film and greatly elaborate on his background and activities prior to the events of the Star Wars films. With the 2012 acquisition of Lucasfilm by The Walt Disney Company, all literature in this category was rebranded as Star Wars Legends and designated as non-canonical to any and all new media released after April 2014.[14][15][16]

Zorba the Hutt's Revenge (1992), a young-adult novel by Paul and Hollace Davids, identifies Jabba's father as another powerful crime lord named Zorba and reveals that Jabba was born 596 years before the events of A New Hope, making him around 600 years old at the time of his death in Return of the Jedi.[17] Four comics exploring Jabba's backstory were written by Jim Woodring and released by Dark Horse Comics in 1995–96; these were collected as Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal in 1998.[18] Ann C. Crispin's novel The Hutt Gambit (1997) explains how Jabba and Han Solo become business associates and portrays the events that lead to a bounty being placed on Han's head.[19]

Tales from Jabba's Palace (1996), a collection of short stories edited by Kevin J. Anderson, pieces together the lives of Jabba the Hutt's various minions in his palace and their relationship to him during the last days of his life. These stories reveal that very few of the Hutt's servants are loyal to him, with many plans underway among their ranks to attempt his assassination. When Jabba the Hutt is killed in Return of the Jedi, his surviving former courtiers join forces with his rivals on Tatooine and his family on the Hutt homeworld Nal Hutta make claims to his palace, fortune, and criminal empire.[20] Timothy Zahn's novel Heir to the Empire (1991) reveals that a smuggler named Talon Karrde eventually replaces Jabba as the "big fish in the pond", and moves the headquarters of the Hutt's criminal empire off of Tatooine.[21]

Potential film project

Lucas has noted that there was a potential role for Jabba in future Star Wars films.[22] In August 2017, a Jabba the Hutt anthology film was reportedly in development alongside an Obi-Wan Kenobi film.[23] Although no cast or crew have been announced, Guillermo del Toro has expressed interest in directing such a project.[24]

Characterization

Jabba the Hutt exemplifies lust, greed, and gluttony.[25] The character is known throughout the Star Wars universe as a "vile gangster"[26] who amuses himself by torturing and humiliating his subjects and enemies. He surrounds himself with scantily-clad slave girls of all species, chained to his dais. The Star Wars Databank remarks that residents of his palace are not safe from his desire to dominate and torture:[27] in Return of the Jedi, the Twi'lek slave dancer Oola is fed to the rancor.[28]

Jabba the Hutt's physical appearance reinforces his personality as a criminal deviant. In Return of the Jedi, Han Solo calls Jabba a "slimy piece of worm-ridden filth". Film critic Roger Ebert described him as "a cross between a toad and the Cheshire Cat."[29] Science fiction writer Jeanne Cavelos wrote that Jabba deserved the "award for most disgusting alien".[30] Science fiction authors Tom and Martha Veitch write that Jabba's body is a "miasmic mass", and that "The Hutt's lardaceous body seemed to periodically release a greasy discharge, sending fresh waves of rotten stench" into the air.[31] Jabba's appetite is insatiable, and some authors portray him threatening to eat his subordinates.[32][33]

Among Jabba's only displays of any positive qualities within the franchise occur in Star Wars: The Clone Wars, where he demonstrates genuine affection for his son Rotta and is worried by his kidnapping and angered by his supposed death. In one Expanded Universe story, Jabba prevents a Chevin named Ephant Mon from freezing to death on an ice planet, whereafter Ephant Mon becomes one of his most loyal servants.[34]

Concept and creation

Episode IV: A New Hope

The original script to Star Wars[a] describes Jabba as a "fat, slug-like creature with eyes on extended feelers and a huge ugly mouth",[12] but Lucas stated in an interview that the initial character he had in mind was much furrier and resembled a Wookiee. When filming the scene between Han Solo and Jabba in 1976, Lucas employed Northern Irish actor Declan Mulholland to stand-in for Jabba the Hutt, wearing a shaggy brown costume. Lucas planned to replace Mulholland in post-production with a stop-motion creature. The scene was meant to connect Star Wars to Return of the Jedi and explain why Han Solo was imprisoned at the end of The Empire Strikes Back.[35] Nevertheless, Lucas decided to leave the scene out of the final film on account of budget and time constraints and because he felt that it did not enhance the film's plot.[36] The scene remained in the novelization, comic book, and radio adaptations of the film.

Lucas revisited the scene in the 1997 Special Edition release of A New Hope, restoring the sequence and replacing Mulholland with a CGI version of Jabba the Hutt and the English dialogue with Huttese, a fictional language created by sound designer Ben Burtt. Joseph Letteri, the visual effects supervisor for the Special Edition, explained that the ultimate goal of the revised scene was to make it look as if Jabba the Hutt was actually on the set talking to and acting with Harrison Ford and that the crew had merely photographed it. Letteri stated that the new scene consisted of five shots that took over a year to complete.[37][38] The scene was polished further for the 2004 release on DVD, improving Jabba's appearance with advancements in CGI techniques, although neither release looks exactly like the original Jabba the Hutt puppet.[39]

At one point of the original scene, Ford walks behind Mulholland. This became a problem when adding the CGI Jabba since his tail would be in the way. The solution was to have Solo step on Jabba's tail, causing him to grunt in pain. In the 2004 DVD release, Jabba reacts more strongly, winding up as if to punch Han. In this version, shadows of Han can be seen on Jabba's body to make the CGI more convincing.

Lucas confesses that people were disappointingly upset about the CGI Jabba's appearance, complaining that the character "looked fake". Lucas dismisses this, stating that whether a character is ultimately portrayed as a puppet or as CGI, it will always be "fake" since the character is ultimately not real. He says he sees no difference between a puppet made of latex and one generated by a computer.[40]

Episode VI: Return of the Jedi

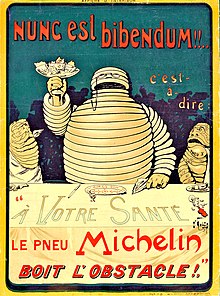

Lucas based the CGI on the character as he originally appeared in Return of the Jedi. In this film, Jabba the Hutt is an immense, sedentary, slug-like creature designed by Lucas's Industrial Light & Magic Creature Shop. Design consultant Ralph McQuarrie claimed, "In my sketches Jabba was huge, agile, sort of an apelike figure. But then the design went into another direction, and Jabba became more like a worm kind of creature."[41] According to the 1985 documentary From Star Wars to Jedi, Lucas rejected initial designs of the character. One made Jabba appear too human—almost like a Fu Manchu character—while a second made him look too snail-like. Lucas finally settled on a design that was a hybrid of the two, drawing for further inspiration on an O'Galop cartoon figure flanking an early depiction of Bibendum (also known as the "Michelin Man").[42] Return of the Jedi costume designer Nilo Rodis-Jamero commented,

My vision of Jabba was literally Orson Welles when he was older. I saw him as a very refined man. Most of the villains we like are very smart people. But Phil Tippett kept imagining him as some kind of slug, almost like in Alice in Wonderland. At one time he sculpted a creature that looked like a slug that's smoking. I kept thinking I must be really off, but eventually that's where it led up to."[43]

Production and design

Designed by visual effects artist Phil Tippett,[44] Jabba the Hutt was inspired by the anatomy of several animal species. His body structure and reproductive processes were based on annelid worms, hairless animals that have no skeleton and are hermaphroditic. Jabba's head was modeled after that of a snake, complete with bulbous, slit-pupilled eyes and a mouth that opens wide enough to swallow large prey, even a humanoid. His skin was given moist, amphibian qualities. Jabba's design would come to represent almost all members of the Hutt species in subsequent Star Wars fiction.[45]

In Return of the Jedi, Jabba is portrayed by a one-ton puppet that took three months and half a million dollars to construct. While filming the movie, the puppet had its own makeup artist. The puppet required three puppeteers to operate, making it one of the largest ever used in a motion picture.[42] Stuart Freeborn designed the puppet, while John Coppinger sculpted its latex, clay, and foam pieces. Puppeteers included David Alan Barclay, Toby Philpott, and Mike Edmonds, who were members of Jim Henson's Muppet group. Barclay operated the right arm and mouth and read the character's English dialogue, while Philpott controlled the left arm, head, and tongue. The tongue was a light beige color and came out of Jabba’s mouth several times. When he encountered Leia Organa for the first time and enslaved her, he extended his tongue and licked at her face. The reason Leia reacted with such disgust upon seeing the tongue, was because in one take, Philpott moved the tongue closer then Carrie Fisher was comfortable with, and it licked her unintentionally. Edmonds, the shortest of the three men (he also played the Ewok Logray in later scenes) was responsible for the movement of Jabba's tail. Tony Cox, who also played an Ewok, would assist as well. The eyes and facial expressions were operated by radio control.[12][40][42]

Lucas voiced displeasure in the puppet's appearance and immobility, complaining that the puppet had to be moved around the set to film different scenes. In the DVD commentary to the Special Edition of Return of the Jedi, Lucas notes that if the technology had been available in 1983, Jabba the Hutt would have been a CGI character similar to the one that appears in the Special Edition scene of A New Hope.[40]

Jabba the Hutt only speaks Huttese on film, but his lines are subtitled in English. His voice and Huttese-language dialogue were performed by voice actor Larry Ward, whose work is not listed in the end credits. A heavy, booming quality was given to Ward's voice by pitching it an octave lower than normal and processing it through a subharmonic generator.[46] A soundtrack of wet, slimy sound effects was recorded to accompany the movement of the puppet's limbs and mouth.[47]

Jabba the Hutt's musical theme throughout the film, composed by John Williams, is played on a tuba.[48] The theme is very similar to one Williams wrote for a heavyset character in Fitzwilly (1967), though the theme does not appear on that film's soundtrack album. Williams later turned the theme into a symphonic piece performed by the Boston Pops Orchestra featuring a tuba solo by Chester Schmitz. The role of the piece in film and popular culture has become a focus of study by musicologists such as Gerald Sloan, who says Williams' piece "blends the monstrous and the lyrical."[49]

According to film historian Laurent Bouzereau, Jabba the Hutt's death in Return of the Jedi was suggested by script writer Lawrence Kasdan. Lucas decided Leia should strangle him with her slave chain. He was inspired by a scene from The Godfather (1972) where an obese character named Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana) is garroted by an assassin.[50]

Portrayal

Jabba the Hutt was played by Declan Mulholland in scenes cut from the 1977 release of Star Wars. In Mulholland's scenes as Jabba, Jabba is represented as a rotund human dressed in a shaggy fur coat. George Lucas has stated his intention was to use an alien creature for Jabba, but the special effects technology of the time was not up to the task of replacing Mulholland. In 1997, the "Special Edition" re-releases restored and altered the original scene to include a computer generated portrayal of Jabba. In Return of the Jedi, he was played by puppeteers Mike Edmonds, Toby Philpott, David Alan Barclay[51] and voiced by Larry Ward. Jabba was voiced by an unknown actor in post-1997 editions of Star Wars and in The Phantom Menace. In The Phantom Menace's end credits, Jabba was jokingly credited as playing himself. His puppeteers have appeared in the documentaries From Star Wars to Jedi: The Making of a Saga and Classic Creatures: Return of the Jedi. David Alan Barclay, who was one of the puppeteers for Jabba in the film, voiced Jabba in the Super NES video game adaptation of Return of the Jedi. In the radio drama adaption of the original trilogy, Jabba is played by Ed Asner. In the film Star Wars: The Clone Wars and the following television series, Jabba is portrayed by Kevin Michael Richardson. All other video game appearances of Jabba were played by Clint Bajakian. Jabba was supposed to appear in Star Wars: The Force Unleashed, but was left out due to time constraints. A cutscene was produced featuring a conversation between Jabba and Juno Eclipse (voiced by Nathalie Cox), which was scrapped from the game. He appears in the Ultimate Sith Edition.

Cultural impact

With the premiere of Return of the Jedi in 1983 and the accompanying merchandising campaign, Jabba the Hutt became an icon of not just Star Wars, but American popular culture as a whole. The character was produced and marketed as a series of action figure play sets by Kenner/Hasbro from 1983 to 2004.[52] In the 1990s, Jabba the Hutt starred in his own comic book series, Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal (a reference to the book of the same title by Donald Trump).[53]

Jabba's role in popular culture extends beyond the Star Wars universe and its fans. In Mel Brooks' Star Wars spoof film Spaceballs (1987), Jabba the Hutt is parodied as the character Pizza the Hutt, a cheesy blob shaped like a slice of pizza whose name is a double pun on Jabba the Hutt and the restaurant franchise Pizza Hut. Like Jabba, Pizza the Hutt is a loan shark and mobster. The character meets his demise at the end of Spaceballs when he becomes "locked in his car and [eats] himself to death."[54]

The Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, included a display on Jabba the Hutt in the temporary exhibition Star Wars: The Magic of Myth, which closed in 1999. Jabba's display was called "The Hero's Return," referencing Luke Skywalker's journey toward becoming a Jedi.[55]

The game "Tongue of the Fatman" is probably based on this character.

Mass media

Since the release of Return of the Jedi, the name Jabba the Hutt has become synonymous in American mass media with repulsive obesity. The name is utilized as a literary device—either as a simile or metaphor—to illustrate character flaws. For example, in Under the Duvet (2001), Marian Keyes references a problem with gluttony when she writes, "wheel out the birthday cake, I feel a Jabba the Hutt moment coming on."[56] Likewise, in the novel Steps and Exes: A Novel of Family (2000), Laura Kalpakian uses Jabba the Hutt to emphasize the weight of a character's father: "The girls used to call Janice's parents Jabba the Hutt and the Wookiee. But then Jabba (Janice's father) died, and it didn't seem right to speak of the dead on those terms."[57] In Dan Brown's first novel Digital Fortress, an NSA technician is affectionately nicknamed Jabba the Hutt.

In his book of humor and popular culture The Dharma of Star Wars (2005), writer Matthew Bortolin attempts to show similarities between Buddhist teachings and aspects of Star Wars fiction. Bartolin insists that if a person makes decisions that Jabba the Hutt would make, then that person is not practicing the proper spiritual concept of dharma. Bortolin's book reinforces the idea that Jabba's name is synonymous with negativity:

One way to see if we are practicing right livelihood is to compare our trade with that of Jabba the Hutt. Jabba has his fat, stubby fingers in many of the pots that led to the dark side. He dealt largely in illegal "spice" trade—an illicit drug in the Star Wars galaxy. He also transacts business in the slave trade. He has many slaves himself, and some he fed to the Rancor, a creature he kept caged and tormented in his dungeon. Jabba uses deception and violence to maintain his position.[58]

Outside literature, the character's name has become an insulting term of disparagement. To say that someone "looks like Jabba the Hutt" is commonly understood as a slur to impugn that person's weight or appearance.[3] The term is often employed by the media as an attack on prominent figures.

In another sense of the term, Jabba the Hutt has come to represent greed and anarchy, especially in the business world.[4] Jabba the Hutt ranked #4 on the Forbes Fictional 15 list of wealthiest fictional characters in 2008.

Jabba the Hutt has likewise become a popular means of caricature in American politics. William G. Ouchi uses the term to describe what he sees as the inefficient bureaucracy of the public school system: "With all of these unnecessary layers of organizational fat, school districts have come to resemble Jabba the Hutt—the pirate leader in Star Wars."[59]

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b Later titled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope

Citations

- ^ a b Sansweet, Steven J. (2008). "Jabba". Star Wars Encyclopedia. New York City: Del Ray Books. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0345477637.

- ^ "Is Jabba the Hutt a Slug?". Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "Fat Wars: The Obesity Empire Strikes Back". consumerfreedom.com. Center for Consumer Freedom. May 26, 2005. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007.

- ^ a b Kuiper, Koenraad (Spring 1988). "Star Wars: An Imperial Myth". Journal of Popular Culture. 21 (4): 78.

- ^ a b Richard Marquand (director) (2005) [1983]. Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, Special Edition, dir. George Lucas (DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2005), disc 1.

- ^ "Mos Espa Grand Arena" at the Star Wars Databank.

- ^ Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, dir. George Lucas (DVD, 20th Century Fox, 1999), disc 1.

- ^ Roy Thomas (w). "Six Against the Galaxy" Marvel Star Wars, no. 2 (August 1977). Marvel.

- ^ Archie Goodwin (w). "What Ever Happened to Jabba the Hut?" Marvel Star Wars, no. 28 (October 1979). Marvel.

- ^ Archie Goodwin (w). "In Mortal Combat" Marvel Star Wars, no. 37 (July 1980). Marvel..

- ^ a b c "Jabba the Hutt, Behind the Scenes". StarWars.com. Star Wars Databank. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Lucas, George (1977). Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker (paperback ed.). New York: Del Rey. p. 107. ISBN 0-345-26079-1.

- ^ McMilian, Graeme (April 25, 2014). "Lucasfilm Unveils New Plans for Star Wars Expanded Universe". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "The Legendary Star Wars Expanded Universe Turns a New Page". StarWars.com. April 25, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ "Disney and Random House announce relaunch of Star Wars Adult Fiction line". StarWars.com. April 25, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ Davids, Paul; Davids, Hollace (1992). Zorba the Hutt's Revenge. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-15889-9.

- ^ Jim Woodring (w). Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal (1998). Dark Horse Comics, ISBN 1-56971-310-3.

- ^ Crispin, Anne C. (1997). The Hutt Gambit. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-57416-7.

- ^ Anderson, Kevin J., ed. (1996). Tales from Jabba's Palace. New York City: Bantam Spectra. ISBN 0-553-56815-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Zahn, Timothy (1991). Heir to the Empire. New York City: Bantam Spectra. p. 27. ISBN 0-553-29612-4.

- ^ Berger, Arthur Asa (May 1984). "Return of the Jedi: The rewards of myth". Society. 21 (4). New York City: Springer Link: 71–75. doi:10.1007/BF02695105. ISSN 1936-4725.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (August 17, 2017). "'Star Wars' Obi-Wan Kenobi Movie in Early Development at Disney". Variety. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Peters, Megan (April 11, 2017). "Star Wars: Guillermo Del Toro Would Make A Jabba The Hutt Movie". Comic Book. Gamespot. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Pomerance, Murray (2004). Schneider, Steven Jay (ed.). "Hitchcock and the Dramaturgy of Screen Violence". New Hollywood Violence. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press: 47. ISBN 0-7190-6723-5.

- ^ From the title crawl of Return of the Jedi; also a description from the Return of the Jedi novelization at Penguin Random House. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ "Jabba the Hutt, The Movies". Star Wars Databank. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Tyers, Kathy (1996). "A Time to Mourn, A Time to Dance: Oola's Tale". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from Jabba's Palace. p. 80.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (May 25, 1983). "Return of the Jedi review". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago: Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Cavelos, Jeanne (1999). Just Because It Goes 'Ho Ho Ho' Doesn't Mean It's Santa: The Science of Star Wars: An Astrophysicist's Independent Examination of Space Travel, Aliens, Planets, and Robots as Portrayed in the Star Wars Films and Books. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-312-20958-4.

- ^ Veitch, Tom; Veitch, Martha (1995). "A Hunter's Fate: Greedo's Tale". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina. New York: Bantam Spectra. pp. 49–53. ISBN 0-553-56468-4.

- ^ Windham, Ryder (1996). "This Crumb for Hire". A Decade of Dark Horse #2. Dark Horse Comics.

- ^ Friesner, Esther M. "That's Entertainment: The Tale of Salacious Crumb". In Anderson, Kevin J. (ed.). Tales from Jabba's Palace. pp. 60–79.

- ^ "Ephant Mon, Expanded Universe". Star Wars Databank. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ George Lucas interview, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, Special Edition (VHS, 20th Century Fox, 1997).

- ^ George Lucas commentary, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, Special Edition, dir. George Lucas, (DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2004).

- ^ Joseph Letteri interview, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope, Special Edition (VHS, 20th Century Fox, 1997).

- ^ "A New Hope: Special Edition — What has changed?: Jabba the Hutt", January 15, 1997, at "A New Hope: Special Edition – What has changed?". Archived from the original on March 1, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2016.. Retrieved July 3, 2006. "A New Hope: Special Edition – What has changed?". Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Star Wars: The Changes — Part One" at DVDActic.com. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ a b c George Lucas commentary, Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi, Special Edition, dir. Richard Marquand (DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2004).

- ^ Ralph McQuarrie, quoted in Laurent Bouzereau, Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays (New York: Del Rey, 1997), p. 239, ISBN 0-345-40981-7.

- ^ a b c From Star Wars to Jedi: The Making of a Saga, narrated by Mark Hamill (1985; VHS, CBS Fox Video, 1992).

- ^ Nilo Rodis-Jamero, quoted in Bouzereau, Annotated Screenplays, p. 239.

- ^ "Biography of Phil Tippett". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2006. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Sansweet, Stephen J. (1998). Hutt. New York: Del Rey. p. 134. ISBN 0-345-40227-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Holman, Tomlinson (2002). Sound for Film and Television. Burlington, Massachusetts: Focal Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-240-80453-8.

- ^ Ben Burtt commentary, Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi, Special Edition, dir. Richard Marquand (DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2004).

- ^ "Review of Return of the Jedi soundtrack". Filmtracks.com. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Sloan, Gerald (June 27, 2000). "Evening The Score: UA Professor Explores Tuba Music In Film". Daily Digest. University of Arkansas. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2006.

- ^ Bourezeau, Laurent (1997). Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. Ballantine Books. p. 259. ISBN 978-0345409812.

- ^ "Dave Barclay". davebarclay.com.

- ^ Carlton, Geoffrey T. (2003). Star Wars Super Collector's Wish Book: Identification & Values. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. p. 13. ISBN 1-57432-334-2. A complete Jabba the Hutt play set sold by Kenner in 1983 was valued at $70 in 2003 by collectors if in mint condition and with original packaging.

- ^ Von Busack, Richard (August 6, 1998). "Jabba the Hutt slimes his way through a new graphic novel". metroactive.com. Metroactive Books. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ Spaceballs, Dir. Mel Brooks (MGM, 1987).

- ^ "The Hero's Return". Star Wars: The Myth of Magic exhibition. National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008..

- ^ Keyes, Marian (2001). Under the Duvet: Shoes, Reviews, Having the Blues, Builders, Babies, Families and Other Calamities. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 199. ISBN 0-06-056208-0.

- ^ Kalpakian, Laura (2000). Steps and Exes: A Novel of Family. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 58. ISBN 0-380-80659-2.

- ^ Bortolin, Matthew (2005). The Dharma of Star Wars. Somerville, Massachusetts: Wisdom Publications. p. 139. ISBN 0-86171-497-0.

- ^ Ouchi, William G. Making Schools Work: A Revolutionary Plan to Get Your Children the Education They Need (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003), p. 96. ISBN 0-7432-4630-6

Further reading

- Mangels, Andy. The Essential Guide to Characters. New York: Del Rey, 1995. ISBN 0-345-39535-2.

- Reynolds, David West. Star Wars Episode I: The Visual Dictionary. New York: DK Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7894-4701-0.

- Wallace, Daniel and Kay How. The New Essential Guide to Characters. New York: Del Rey, 2002. ISBN 0-345-44900-2.

- Wallace, Daniel, and Kevin J. Anderson. The New Essential Chronology. New York: Del Rey, 2005. ISBN 0-345-49053-3.

- Wixted, Martin. Star Wars Galaxy Guide 7: Mos Eisley. Honesdale, Penn.: West End Games, 1993. ISBN 0-87431-187-X.

External links

- Jabba the Hutt in the StarWars.com Databank

- Jabba Desilijic Tiure on Wookieepedia, a Star Wars wiki

- Characters created by George Lucas

- Film characters introduced in 1983

- Fictional asexuals

- Fictional crime bosses

- Fictional drug dealers

- Fictional gangsters

- Fictional gamblers

- Fictional torturers

- Fictional kidnappers

- Extraterrestrial supervillains

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in television

- Star Wars CGI characters

- Star Wars puppets

- Star Wars Skywalker Saga characters

- Male film villains

- Return of the Jedi