Evo Morales: Difference between revisions

Some good reliable sources would be needed to include these edits |

Garcialinera (talk | contribs) Despite some supporters reluctance to get these facts displayed, they are ready to be read again |

||

| Line 159: | Line 159: | ||

The presidential spokesman, [[Ivan Canelas]] later pointed out that Morales had not referred to homosexuals in his speech. He went on to highlight the fact that the new Bolivian Constitution, supported by Morales, makes Bolivia "one of the few countries that has a deep respect for all sectors and options... [the new constitution] establishes that 'all forms of discrimination are prohibited on the grounds of sex, colour, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, origin, culture, nationality, citizenship, language, religious creed, ideology, political or philosophical affiliation, civil status, social or economic condition, type of occupation, level of education, disability, pregnancy or others...'". He added that on 1st June 2009 the government had passed a supreme decree declaring 28th June to be a national day of the rights of people with diverse sexual orientation in Bolivia.<ref>[http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/04/27/index.php?section=mundo&article=026n1mun&partner=rss Evo Morales no pretendió atacar derechos de homosexuales: vocero, La Jornada, Martes 27 de abril de 2010]</ref> |

The presidential spokesman, [[Ivan Canelas]] later pointed out that Morales had not referred to homosexuals in his speech. He went on to highlight the fact that the new Bolivian Constitution, supported by Morales, makes Bolivia "one of the few countries that has a deep respect for all sectors and options... [the new constitution] establishes that 'all forms of discrimination are prohibited on the grounds of sex, colour, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, origin, culture, nationality, citizenship, language, religious creed, ideology, political or philosophical affiliation, civil status, social or economic condition, type of occupation, level of education, disability, pregnancy or others...'". He added that on 1st June 2009 the government had passed a supreme decree declaring 28th June to be a national day of the rights of people with diverse sexual orientation in Bolivia.<ref>[http://www.jornada.unam.mx/2010/04/27/index.php?section=mundo&article=026n1mun&partner=rss Evo Morales no pretendió atacar derechos de homosexuales: vocero, La Jornada, Martes 27 de abril de 2010]</ref> |

||

===Personal life=== |

===Personal life: fatherhood=== |

||

“I love to make women cry” said to the camera, Evo Morales Ayma, a long while before his election as President of Bolivia<ref> http://video.aol.com/video-detail/evo-morales-me-gusta-hacer-llorar-a-las-mujeres/1291190293%20-%2066k</ref>. The head of government and his romantic relationships with the mothers of his daughter and youngest son ended on demands for parenthood and children support payments. |

|||

Morales fathered Eva Liz Morales Alvarado, born on September 24th of 1994, and Alvaro Morales Peredo, out of wedlock. |

|||

Morales fathered Eva Liz Morales Alvarado, born on September 24th of 1994 and Alvaro Morales Peredo, both extra marital children brought into life by Francisca Alvarado, former leader of the political party Eje Pachakuti and Marisol Peredo, a teacher, respectively. |

|||

| ⚫ | On 2001, Francisca Alvarado |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | On 2001, Francisca Alvarado claimed that Morales, a member of Congress by then, was reluctant to acknowledge her five year old daughter, Eva Liz and supply the child with a maintenance fee <ref> http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo</ref> . On January 30th in 2001, Alvarado set a fatherhood claim upon the Family Court in Oruro, Bolivia to get her daughter recognized by her father and also, the mandated child support payments,<ref>http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo</ref> but the accused denied fatherhood and any release of financial support<ref> http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo</ref>. |

||

In spite of his defense, the Chamber of Deputies was recommended to punish Morales with the loss of his seniority and privileges if the representative refused a DNA test. An official resolution was ready on the 30th of October to punish him but the legal statement was not going to be executed because Morales Ayma would finally agree to recognize his daughter in exchange for a political “joint agreement” <ref>http://www.eldeber.com.bo/anteriores/20011003/nacional_4.html</ref>. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

But on 2004, Morales attorney delivered a Habeas Corpus Resource against the Judge who issued a jail order against Evo, because this one was indebting children financial support to Alvaro, his youngest son, alleging that his client enjoyed parliamentary immunity from prosecution and imprisonment. However, on June 23rd of 2004, the Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal, submitted the 0977/2004R resolution sentencing that “Evo Morales deputy must look after his son’s life, health, safety and education” and “parliamentary immunity shall not be advocated when fundamental human rights are endangered. This jurisprudence line fits this court case as Evo Morales Ayma is threatening his son fundamental rights when the mandated child support payments are not cancelled on time”<ref> http://www.tribunalconstitucional.gob.bo/resolucion9719.html</ref> . Lastly, the Chief Clerk's Office at the Chamber of Representatives, retained the owed amount of money out of the congressman salary to honor such family duty.<ref>http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 21:28, 19 May 2010

Evo Morales | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Bolivia | |

| Assumed office January 22, 2006 | |

| Vice President | Álvaro García Linera |

| Preceded by | Eduardo Rodríguez |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 October 1959 Orinoca, Oruro, Bolivia |

| Political party | MAS |

| Occupation | Unionist |

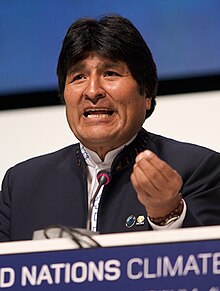

Juan Evo Morales Ayma (born October 26, 1959), popularly known as Evo (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈeβo]), has been the President of Bolivia since 2006. Morales was first elected President of Bolivia on December 18, 2005, with 53.7% of the popular vote (approximately 45% of the electorate) in an election that saw the participation of 84.5% of the national electorate.[3] Two and a half years later he substantially increased this majority; in a recall referendum on August 14, 2008, more than two thirds of voters (67.4%) voted to keep him in power (approximately 57% of the electorate).[4] Morales won presidential elections again in December 2009 by 63% and continued to his second term of presidency.[5]

Morales is the leader of a political party called the Movement for Socialism (Movimiento al Socialismo, with the Spanish acronym MAS, meaning "more"). MAS was involved in social protests such as the gas conflict and the Cochabamba protests of 2000, along with many other groups, that are collectively referred to as "social movements" in Bolivia. The MAS aims at giving more power to the country's indigenous and poor communities by means of land reforms and redistribution of gas wealth.[6]

Morales is also titular president of Bolivia's cocalero movement – a loose federation of coca growers' unions, made up of campesinos (rural laborers) who are resisting the efforts of the United States government to eradicate coca in the province of Chapare in central Bolivia. In October 2009, Morales was named "World Hero of Mother Earth" by the United Nations General Assembly.[7]

Background

Morales was born in the highlands of Orinoca, Oruro. He is of indigenous Aymara descent.[8] He was one of seven children born to Dionisio Morales Choque and Maria Mamani; only Morales and two of his siblings survived past childhood.[9] He grew up in an adobe house with a straw roof that was "no more than three by four meters."[9] At age six, he traveled with his father to Argentina to work in the sugar cane harvest.[9] As is customary for the Aymara people, his parents made offerings of coca leaves and alcohol to mother earth, or Pachamama.[9] At the age of 12, he accompanied his father in herding llamas from Oruro to the province of Independencia in Cochabamba.[9]

When he was 14, Morales showed his organizational skills by forming a soccer team with other youths; he continued herding llamas to pay the bills.[10] Three ayllus (network of families) within the community elected him technical director of selection for the canton's team when he was only 16 years old.[10] That same year, in order to attend high school, he moved to Oruro. There he worked as a bricklayer, a baker, and a trumpet player for the Royal Imperial Band (which allowed him to travel across Bolivia).[11][10][12] He attended Beltrán Ávila High School but was not able to finish school,[13] and fulfilled his mandatory military service in La Paz.[10][14]

Ethnicity

Evo Morales has declared himself the first Amerindian president, a controversial claim due to the Amerindian heritages of such prior Bolivian presidents as Andrés de Santa Cruz (1829—who claimed that through his mother he was descended from Inca rulers[citation needed]), Mariano Melgarejo (1864), Carlos Quintanilla (1939), René Barrientos (1964), Juan José Torres (1976), Luis García Meza (1980), and Celso Torrelio (1981).[15] However, none of these presidents were democratically elected, with the exception of Barrientos with the full support (and no doubt, electoral "help") of the Bolivian military establishment. While the claim is a potent symbol, it has been challenged publicly by the novelist and erstwhile right-wing Peruvian presidential candidate Mario Vargas Llosa,[16] who accuses Morales of fomenting racial divisions in an increasingly mestizo[17] Latin America.

The Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano responded to Vargas Llosa saying: "I see what is happening in Bolivia as a very significant act of affirmation of diversity [which is opposite to] racism, elitism and militarism, which leave us blind to our marvellous existence, to that rainbow that we are".[18]

Farming in the lowlands

In 1980, while Morales was in his 20s, the effects of El Niño caused a 70% decline in agriculture and killed 50% of the animals in his home region. Evo joined the Morales family when they left Orinoca to participate in the colonization of the tropics of Cochabamba, located in the eastern Bolivian lowlands.[10][12] Working on his family's land, he grew crops of oranges, grapefruit, papaya, bananas and coca.[19] Morales soon joined a trade union of coca growers. Morales claims on his website that by 1981, he became motivated to defend his fellow coca farmers after learning that one of them had been beaten, covered in gasoline, and burned alive by drunken soldiers of the government of Luis García Meza.[19] In 1981, he was made the head of his local soccer organization; after his father's death in 1983, he was forced to give up that position in order to concentrate on managing his family's farm.[19]

Union activity

By 1985, Morales was elected general secretary in a union of coca farmers and by 1988 was elected executive secretary of the Tropics Federation.[19] He retains this position to this day, even while serving as president of Bolivia. Around this time the Bolivian government, encouraged by the US, began a program to eradicate most coca production. By 1996 Morales was made president of the Coordinating Committee of the Six Federations of the Tropics of Cochabamba.[19] Morales was among those opposing the government's position on coca and lobbied for a different policy. This opposition often resulted in him being jailed and in an incident in 1989, beaten near to death by UMOPAR forces (who, assuming he had been slain, dumped his unconscious body in the bushes where it was discovered by his colleagues).[19]

Morales soon led a 600 km march from Cochabamba to the Bolivian capital La Paz. While they were often attacked by law enforcement officers, they managed to proceed by sneaking around their control posts.[19] They were often greeted by supporters who gave the marchers drink, food, clothes and shoes. They were greeted with cheers by supporters in La Paz and the government was forced to negotiate an accord with them.[19] After the marchers returned home, the government reneged on the deal and sent forces to harass them.[19] Morales claims that during this time in 1997 a United States Drug Enforcement Agency helicopter strafed farmers with automatic rifle fire, killing five of his supporters.[19] He also claims he was grazed by assassins' bullets in Villa Tunari in 2000.[19] He was recognized in 1996 by an international coalition against the "War on Drugs".[19] Morales then found an audience in Europe for his positions and traveled there to gain support and to educate people on the differences between coca leaves and cocaine.[19] In a speech on this issue, he told reporters "I am not a drug trafficker. I am a coca grower. I cultivate coca leaf, which is a natural product. I do not refine (it into) cocaine, and neither cocaine nor drugs have ever been part of the Andean culture."[11]

Style

His behavior contrasts with the usual manners of dignitaries in Latin America. For example, in January 28, 2006 he cut his salary by 57% to $1,875 a month.[20] He is single and, before the election, he shared a flat with other MAS officers. Consequently, his older sister Esther Morales Ayma fulfills the role of First Lady. He has two children from different mothers.[21] Morales is also an association football enthusiast and plays the game frequently, often with local teams.[22]

He also aroused much interest in his choice of dress after being pictured often in his striped sweater with world leaders during his world tour. Some speculated that he would wear it to the official inauguration, where he actually dressed in a white shirt without tie (itself unheard of in Latin America in modern times for a head of state at their own inauguration) and a black jacket that was not a part of a conventional suit. The sweater (in Bolivian Spanish, a chompa, from the English word jumper) became his unofficial symbol and copies of it sold widely throughout Bolivia.[23] Some accounts described Morales's signature sweater as alpaca-wool; others reported that it was actually made of common acrylic, because native materials had become too expensive for most Bolivians and were sold mostly in the tourist trade.[24]

Additionally, Morales is an outspoken supporter of the iconic Argentine Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, who was executed by CIA-assisted Bolivian soldiers in 1967. At a ceremony in Vallegrande, marking the 42nd anniversary of Che's death, Morales remarked that "Guevara is invincible in his ideals, and in all this history, after so many years, he inspires us to continue fighting, changing not only Bolivia, but all of Latin America and the world."[25] As an additional sign of admiration, Morales has had a coca leaf portrait of Guerrillero Heroico installed in the presidential palace.[26]

Early political activity

1995 election, formation of MAS

On March 27, 1995, Morales was among a united organization of farmers, colonizers and indigenous people who founded the Assembly for the Sovereignty of the Common People (ASP) and the Political Tool for the Sovereignty of the Common People (IPSP).[27] Morales and others decided to run for political office in Bolivia under this party. Since the National Electoral Court did not recognize the new organization they were forced to run under the banner of the United Left (IU), "a coalition of leftist parties that was headed by the Communist Party of Bolivia (PCB)."[27] On June 1, 1997, Morales (who carried 70% of the votes in his electoral district) was one of four IU candidates that won a seat in Congress. The area he represented included the provinces of Chapare and Carrasco and Morales received the most votes of any candidate in Bolivia.[27] Facing continual legal problems because the Bolivian Supreme Court continued to refuse to recognize IPSP,[14] for the local elections of December 5, 1999, Morales came to an agreement with the leader of MAS-U, David Añez Pedraza, to assume the acronym, name and colors of that inactive organization. So the IPSP became the Movimiento al Socialismo or Movement Towards Socialism (MAS).[27] The MAS is described as "an indigenous-based political party that calls for the nationalization of industry, legalization of the coca leaf … and fairer distribution of national resources."[28]

Expulsion from Congress

While Morales was a Member of Congress, the governments of Hugo Banzer and Jorge Quiroga broadened the eradication campaign through Plan Dignidad. The coca producing region of Chapare which Morales represented was beset with hundreds of police and military officers who were seen by Morales as "committing an innumerable amount of abuses and assassinations which violated the most basic human rights and liberties."[27] Morales denounced the militarization and said that the government was committing a massacre in the Chapare, he declared that the peasants had a right to resist militarily against the troops who were said to be shooting at protesters.[27] Then three police officers were slain when they attempted to close a coca market.[14] In light of Morales' comments about armed resistance on January 24, 2002 a 104-member majority of Congress voted to have him expelled. The Congressional Ethics Commission declared that Morales had committed "serious inadequacies in the execution of his duties."[27] With his popularity rising for standing up to an unpopular government, on March 5, 2002, he submitted an objection to the Constitutional Tribunal saying his rights had been violated. He said his right to defend himself, to the presumption of innocence, and to parliamentary immunity had all been unjustly ignored.[27]

In an interview in November 2002 with The Ecologist, Morales spoke about the expulsion saying "I was the congressman with the highest proportion of votes for his area and ‘obeying an order from the US’ they voted to expel me from Congress. It is only recently that the constitutional court finally declared the whole farce illegal, and now they are having to pay compensation for what they did."[14]

The 2002 elections

The same day he petitioned the Constitutional Tribunal, Morales resigned from the Confederation of Coca Producers of Cochabamba and was endorsed by the Six Federations of the Tropics as the MAS 2002 presidential candidate.[27] The supportive crowd cheered him on saying "Kausachum coca!" ("Long live coca!") and "Huaiñuchum yanquis!" ("Down with Yankees!"), they also "hoisted the wiphala, the multi-colored checkered flag that is the emblem of the Andean cultures, along with the standard tri-colored Bolivian flag."[27]

In the 2002 presidential election, Morales came in second place, a surprising upset for Bolivia's traditional parties. This made the indigenous activist an instant celebrity throughout the continent. Morales credited his near victory in part to comments made by then U.S. Ambassador to Bolivia Manuel Rocha, who warned, "As a representative of the United States, I want to remind the Bolivian electorate that if you elect those who want Bolivia to become a major cocaine exporter again, this will endanger the future of U.S. assistance to Bolivia."[29] Morales said that these remarks helped to "awaken the conscience of the people."

The 2005 elections

In 2005, President Carlos Mesa resigned under pressure by MAS and their supporters, led by Morales, by means of road blocks and riots[30][31]. Because of this, and as a result of growing discontent and popular unrest, Congress and President Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé decided to move up the 2007 elections to December 2005.

At a gathering of farmers celebrating the 10th anniversary of the founding of MAS in March 2005, Morales declared, "MAS is ready to rule Bolivia", having "consolidated its position as the [prime] political force in the country". He also said, "the problem is not winning the elections anymore but knowing how to rule the country."[32]

Preliminary polls placed Morales and the Movement Toward Socialism in an uncomfortable three-way tie with center and right wing forces and urban majority leaders Jorge Quiroga, from the party Social and Democratic Power (PODEMOS), and Samuel Doria Medina, with only a few points' difference. By August 21, Morales had chosen his running mate for the presidential elections, left-wing ideologist, sociologist, mathematician, and political analyst Álvaro García Linera, who fought alongside of Felipe Quispe as part of the Tupac Katari Guerrilla Army (EGTK).

By December 4, Morales had moved ahead in the polls to around 32% of the vote. Quiroga hovered around 27% with Samuel Doria Medina coming in at less than 15%. All of the parties promised national solidarity, nationalization (in some form) of the hydrocarbons, and wealth for the people.

On December 14, the Wall Street Journal reported, "Most polls give the 46-year-old Mr. Morales a lead of about 34% to 29% over his nearest rival, conservative former President Jorge Quiroga." Over 100,000 election judges were sworn in as the country prepared for the elections on December 18.

Exit polls were published almost as soon as voting closed, with Morales expected to win 42–45% of the vote and Quiroga 33–37%. Quiroga conceded defeat within a few hours.

By December 22, the official count was at 53.899% of the vote, with 98.697% of the ballots tallied, and no congressional vote was necessary to determine the winner.

Inauguration

On January 21, 2006, Morales attended an indigenous spiritual ceremony at the pre-Columbian archaeological site and modern spiritual center of Tiwanaku where he was crowned as Apu Mallku or Supreme Leader of the Aymara, the indigenous group to which Morales belongs, and received gifts from many groups representing indigenous peoples from various parts of Latin America and the world. Morales claims this is the first time since the days of Tupac Amaru that an indigenous person has held sovereign power in Bolivia. The ceremony was attended by the Slovenian president, Janez Drnovšek.[33]

On January 22 he officially received power in a ceremony in La Paz attended by multiple heads of state, including Argentine President Néstor Kirchner and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.[34] Chilean President Ricardo Lagos, whose country has had a history of diplomatic conflict with Bolivia (see War of the Pacific) was also present and met with the dignitary in private. Morales described his presidency as marking a new era, and that the 500 years of colonialism were now at an end.

Domestic policy

Foreign policy

Controversies

Conflict with Reyes Villa

Among Morales's most outspoken political opponents is Cochabamba Governor Manfred Reyes Villa. In early 2007 his opposition to Morales' policies inspired many of the President's supporters to take to the streets and demand his resignation. As the group interacted with police and Reyes Villa's supporters events escalated into violence, leaving two dead and 100 injured before calm could be restored.

Ponchos Rojos

On January 23, 2007, Morales and Bolivian military chiefs attended an indigenous peoples rally of the "Red Ponchos" (Ponchos Rojos) who support him in the Andean region of Omasuyos. At the rally Morales thanked the group, saying "I urge our Armed Forces along with the ‘Ponchos Rojos’ to defend our unity and our territorial integrity." Because the group is seen as armed and militant by Morales's opposition they accused him and the Armed Forces of supporting "illegal militias."[35] The rally was held in Achacachi which during the 1970s was the center of the leftist guerrilla movement EGTK (Tupac Katari Guerrilla Army) which had Morales' vice president Álvaro García Linera in their membership.[36] To the cheers of the crowd Morales chastised those calling for regional autonomy saying, "No caballero [a term for white colonizers] will be able to split apart Bolivia."[36]

Advisor faces terrorism charges in Peru

Walter Chávez resigned on February 1, 2007, after being indicted for acts of terrorism in his native country of Peru, which seeks his extradition. Chavez fled Peru following the 1992 coup by Alberto Fujimori, to Bolivia. There, he sought and gained refugee status after presenting his case to the Bolivian government and the United Nations. For 15 years, Chavez made a name for himself in public life as a journalist for numerous newspapers, including La Razon—perhaps Bolivia's most important daily newspaper.

Chávez was hired by the Morales’ Presidential campaign and continued on as media advisor for the Presidency once Morales took office. Peruvian authorities accuse him of "having been a member of the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement guerrilla group that carried out bombings and kidnappings in the 1980s and 1990s."[37] The specific charges against Chávez is that he was "a MRTA member who extorted two Peruvian businessmen on behalf of the group in 1990. …[that same year] Chávez was arrested after receiving $10,000 from one of the men, was released on bail a month later and in 1992 fled to Bolivia."[37] He is also accused "of receiving $5,000 in another case."[38] Chávez has repeatedly denied the charges, saying "They accused me of being part of an MRTA cell but they never proved anything against me."[38]

The resignation came as the Bolivian Senate (which is led by an alliance of opposition parties) announced its intention to rapidly investigate the extent of "Chávez's duties and how he obtained residency in the country."[38] Peruvian television, Bolivian newspapers and the Miami Herald were also pursuing the story with ever more vigor, in the days leading to Chávez leaving the Morales government. He explained his resignation to the Miami Herald, saying that "A lot of things have been said that weren't true. This is beginning to hurt the government."[37] In 2006, Peru had quietly asked for the extradition of Chávez but was turned down as he had been granted political asylum by the Bolivian government. Peru announced that it would be re-filing its extradition request. Chávez said he has no plans to defend himself in court by going to Peru.[37]

Miners protest

In early February 2007, parts of the Bolivian region of La Paz were brought to a standstill as 20,000 miners took to the roads and streets to protest a tax hike to the Complementary Mining Tax (ICM) by the Morales government.[39][40] The protesting miners threw dynamite and clashed with those passing by. The Morales government had attempted to head-off the demonstration by announcing on February 5, 2007, that the tax increase was not directed at the 50,000 miners who are co-op members but at larger private mining companies.[39] This did not dissuade the thousands of protestors who had already gathered nearby the capital in the less affluent city of El Alto.[41]

Movements for regional autonomy

Morales's economic policies have generated opposition from some departments, including Santa Cruz, which have oil and agricultural resources. Political parties that oppose Morales, along with pro-market groups disrupted the workings of Bolivia's Constitutional Assembly by disputing voting mechanisms within the assembly and then by introducing a divisive debate about which city should be Bolivia's capital.[42] Four of the country's nine governors are also demanding more autonomy from the central government and a larger share of government revenues.

The four are the governors of Santa Cruz, Chuquisaca, Beni, and Tarija. The remaining five governors are part of Morales's Movimiento al Socialismo party.[36][43] They are among the first generation of popularly (directly) elected governors. Before December 2005, all governors were political appointees of the President.[43]

The call for autonomy comes mainly from the wealthy lowland regions of Bolivia, which are centers of opposition against Morales. It has been alleged that the autonomy question "has relatively little to do with language, culture, [and] religion… it is mostly about money and resources — specifically, who controls Bolivia's valuable natural gas reserves, second largest in South America after Venezuela's."[36] There are also racial overtones to the autonomy movement, quasi-fascist groups such as the Nación Camba and the Unión Juvenil Cruceñista use violence and intimidation tactics against indigenous groups, using autonomy as a tool to subvert the elected government.[44] The UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, also published a report on the situation in Santa Cruz following a visit in December 2007 and observed that the political climate had give rise to ‘manifestations of racism more suited to a colonial society than a modern democratic state’.[45][46]

Morales sees some of the calls for autonomy as an attempt to disintegrate Bolivia and has vowed to fight them. He has "repeatedly charged that rich landowners and businesspeople from the eastern city of Santa Cruz, an anti-Morales stronghold, were fomenting and funding the autonomy movement in a bid to grab national resources."[36]

Four departments, Santa Cruz, Tarija, Beni and Pando, announced in December 2007, shortly after the proposal of a new Bolivian constitution, that they would seek more autonomy and self-government.[47][48] Santa Cruz and Beni called referendums on autonomy which were held on May 4, 2008 and June 1, 2008 respectively. However, the autonomy statutes which they have proposed have been declared illegal and unconstitutional by the National Electoral Court of Bolivia.[49][50]

On May 4, 2008, authorities in Santa Cruz held a local referendum on the autonomy statutes that had been presented in December 2007. The scheduled referendum vote was struck down by Bolivia's National Electoral Court and no international observers were present, as both the Organization of American States and the European Union declined to send observers.[51] There was a high rate of abstention from the referendum and some polling booths were blocked and ballot boxes destroyed.[52] Protests were somewhat pronounced in areas of major immigration from the western highlands, like Yapacani and San Julián, as well as in areas under indigenous control. In Guaraní territory, ballot boxes were burned in a rejection of the legitimacy of the vote. There were also allegations of fraud and ballot box interference. Reports allege that ballot boxes were delivered already containing pre-marked ballot papers on which crosses had been placed next to the YES option.[52] Many of the protesters accused Santa Cruz leaders of trying to secede from Bolivia and expressed support for a draft constitution written by Bolivia's Constituent Assembly that grants several different levels of autonomy including departmental and indigenous autonomy. Despite this, results showed 85% approval for the autonomy statute, though abstention was recorded at 39%. The Santa Cruz autonomy movement conflicts with the constitutional reform proposed by Evo Morales, who seeks to create, as Morales and his supporters perceive it, a fairer state which includes full rights and recognition of the previously marginalized indigenous majority.[53]

The results thrilled leaders in the eastern Bolivian province of Santa Cruz, who had defied the order of the National Electoral Court, the Congress and President Evo Morales by putting the statute up for a vote. The statute would give the department additional powers such as the right to form its own police, set tax and land-use policies and elect a governor.

On May 8, the National Congress passed a law establishing a recall election for the mandates of the President, Vice President and eight of the nine departmental Prefects (six of whom were sympathetic to the opposition). President Evo Morales supported this initiative.[54][55]

The elements of the autonomy movement came to the fore in the city of Sucre on May 24, 2008. Peasants from settlements outside Sucre came to the centre of the city to participate in a ceremony with President Morales. Instead they were accosted by an aggressive group of young people and marched to Sucre's central square. There they were made to strip to the waist and burn their ponchos, the flag of the MAS party and the wiphala (the flag of the Aymara). While they were doing this they were forced to shout anti-government slogans and were physically assaulted. Present in the square at the time were Jorge "Tuto" Quiroga, former president and leader of the opposition party Podemos, opposition Senator Oscar Ortiz and Prefect of Cochabamba, Manfred Reyes Villa.[56] After these events the government declared it to be a "day of national shame".

Evo Morales and the MAS government have now adopted autonomy as a government policy and departmental autonomies are recognised in the new Bolivian constitution, approved in a referendum in January 2009. As well as departmental autonomy, the new constitution recognises municipal, provincial and indigenous autonomies.[57][58]

Recall Referendum

On August 10, 2008, a recall referendum was held in Bolivia on the mandates of President Evo Morales, his Vice-president Alvaro Garcia Linera and eight of the nine regional prefects. Evo Morales won the referendum with a resounding 67% 'yes' vote, and he and Garcia Linera were ratified in post.[59] Two of the prefects, both aligned with the political opposition in the country, failed to gain enough support and had their mandates recalled with new prefects to be elected in their place.[59] The elections were monitored by over 400 observers, including election observers from the Organization of American States, European Parliament and Mercosur.[59]

Alleged assassination attempt

On April 16, 2009, Bolivian police killed three men and arrested two others in what was an "assassination plot" against Morales.[60] The three men were all foreigners: Eduardo Rózsa-Flores, from Hungary; Michael Dwyer, from Ireland; and Arpad Magyarosi, from Romania. Police said the men discussed bombing a boat on Lake Titicaca where Morales and his cabinet had been meeting on April 3, 2009.[61]

April 2010 environmental conference

The Bolivian government hosted the World People's Conference on Climate Change in Cochabamba and Tiquipaya during late April 2010. In his opening address to the conference, Evo Morales spoke on the theme of comprehensive changes to economies and societies to respond to ecological crisis. During the speech, Morales warned of his belief that chicken producers inject chicken with female hormones "and because of that, men who consume them have problems being men." He also suggested it could also lead to baldness.[62] prompting laughter among the crowd.[63] His comments were described as homophobic by the leading Spain's National Federation of Lesbians, Gays, Transsexuals and Bisexuals, which delivered a letter to the Bolivian embassy in Madrid in protest. President of Homosexual Community Argentina Cesar Cigliutt labeled his remarks "an absurdity". [64]

The presidential spokesman, Ivan Canelas later pointed out that Morales had not referred to homosexuals in his speech. He went on to highlight the fact that the new Bolivian Constitution, supported by Morales, makes Bolivia "one of the few countries that has a deep respect for all sectors and options... [the new constitution] establishes that 'all forms of discrimination are prohibited on the grounds of sex, colour, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, origin, culture, nationality, citizenship, language, religious creed, ideology, political or philosophical affiliation, civil status, social or economic condition, type of occupation, level of education, disability, pregnancy or others...'". He added that on 1st June 2009 the government had passed a supreme decree declaring 28th June to be a national day of the rights of people with diverse sexual orientation in Bolivia.[65]

Personal life: fatherhood

“I love to make women cry” said to the camera, Evo Morales Ayma, a long while before his election as President of Bolivia[66]. The head of government and his romantic relationships with the mothers of his daughter and youngest son ended on demands for parenthood and children support payments.

Morales fathered Eva Liz Morales Alvarado, born on September 24th of 1994 and Alvaro Morales Peredo, both extra marital children brought into life by Francisca Alvarado, former leader of the political party Eje Pachakuti and Marisol Peredo, a teacher, respectively.

On 2001, Francisca Alvarado claimed that Morales, a member of Congress by then, was reluctant to acknowledge her five year old daughter, Eva Liz and supply the child with a maintenance fee [67] . On January 30th in 2001, Alvarado set a fatherhood claim upon the Family Court in Oruro, Bolivia to get her daughter recognized by her father and also, the mandated child support payments,[68] but the accused denied fatherhood and any release of financial support[69].

In spite of his defense, the Chamber of Deputies was recommended to punish Morales with the loss of his seniority and privileges if the representative refused a DNA test. An official resolution was ready on the 30th of October to punish him but the legal statement was not going to be executed because Morales Ayma would finally agree to recognize his daughter in exchange for a political “joint agreement” [70]. Not very long after, Morales would accuse a politician, Sergio Cardenas, of “bringing into play a woman to discredit me”. [71]

But on 2004, Morales attorney delivered a Habeas Corpus Resource against the Judge who issued a jail order against Evo, because this one was indebting children financial support to Alvaro, his youngest son, alleging that his client enjoyed parliamentary immunity from prosecution and imprisonment. However, on June 23rd of 2004, the Bolivian Constitutional Tribunal, submitted the 0977/2004R resolution sentencing that “Evo Morales deputy must look after his son’s life, health, safety and education” and “parliamentary immunity shall not be advocated when fundamental human rights are endangered. This jurisprudence line fits this court case as Evo Morales Ayma is threatening his son fundamental rights when the mandated child support payments are not cancelled on time”[72] . Lastly, the Chief Clerk's Office at the Chamber of Representatives, retained the owed amount of money out of the congressman salary to honor such family duty.[73]

See also

References

- ^ Agencia Boliviana de Informacion

- ^ Evo Morales consecrated Spiritual Leader of Native Religion

- ^ http://www.evomorales.net/paginasEng/perfil_Eng_poder.aspx

- ^ http://www.economist.com/world/americas/displaystory.cfm?story_id=11920813

- ^ Guardian.co.uk - Evo Morales wins landslide victory in Bolivian presidential elections Retrieved on 18 December 2009

- ^ "Chavez acts over US-Bolivia row". BBC News. September 12, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Morales Named "World Hero of Mother Earth" by UN General Assembly by the Latin American Herald Tribune

- ^ Bolivia's new leader vows change

- ^ a b c d e "Evo Morales profile > childhood". Retrieved on February 13, 2007

- ^ a b c d e "Evo Morales — profile > youth". Retrieved on February 13, 2007

- ^ a b "Profile: Evo Morales". BBC News Online. December 14, 2005.

- ^ a b "Bolivia's Morales plans referendum on coca". MSNBC. December 20, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2007.

- ^ Evonobel2007.com Retrieved on November 13, 2007

- ^ a b c d Benjamin Blackwell (November 11, 2002). "From Coca to Congress". The Ecologist. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ Mesa, José, Gisbert, Teresa, Mesa Gisbert, Carlos D. Historia de Bolivia: Segunda Edición corregida y actualizada. Editorial Gisbert. La Paz, 1998

- ^ "Vargas Llosa: "un nuevo racismo"". BBC Mundo. January 21, 2006.

- ^ "Los Tiempos: "Bolivia: A Country of Mestizos"". HACER. March 15, 2009.

- ^ "Galeano le contesta a Vargas Llosa" (in Spanish). BBC. 2006-01-22. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Evo Morales — profile > coca farmer". Retrieved on February 13, 2007

- ^ "Bolivian president slashes salary for public schools". USA Today. January 28, 2006. Retrieved on February 1, 2007.

- ^ Template:Es icon "Hermana de Evo Morales sera primera dama". Es Más. February 5, 2007.

- ^ "Footballing president breaks nose". BBC News Online. July 31, 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ^ "'Evo Fashion' arrives in Bolivia". BBC News Online. 20 January 2006. Retrieved on February 1, 2007.

- ^ "Morales to Ban Used Clothing in Bolivia". Salon.com. 17 July 2007. Retrieved on July 18, 2007.

- ^ Bolivian Leader Joins in Tribute to Che Guevara Associated Press, October 8, 2009

- ^ Image of Morales' new coca leaf portrait of Che Guevara in the Presidential Palace

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Evo Morales: profile > member of parliament". Retrieved on February 13, 2007

- ^ America Vera-Zavala (December 18, 2005). "Evo Morales Has Plans for Bolivia". In These Times. Retrieved February 7, 2007.

- ^ Erin Ralston (July 15, 2002). "Evo Morales and opposition to the US in Bolivia". ZNet. Retrieved February 1, 2007.

- ^ Terra Networks Online Newspaper Mesa resigns as President of Bolivia presed by demonstrators

- ^ BBC Mundo New Road Blocks in Bolivia

- ^ "No Registrado". Prensa Latina. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ^ "President Drnovšek attends the inauguration of the new president of Bolivia". Ljubljana. January 21, 2006. Retrieved on February 2, 2007.

- ^ CNN http://edition.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/americas/01/22/bolivia.list.ap/.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Bolivia's Morales reshuffles cabinet and ratifies reforms". MercoPress. January 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Patrick J. Mcdonnell (January 28, 2007). "Morales faces middle-class protests in Bolivia". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on January 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Tyler Bridges (February 2, 2007). "Morales aide resigns over terror uproar". Miami Herald. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c Álvaro Zuazo (January 30, 2007). "Peru Wants Adviser of Bolivian President". Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ a b "Clashes as Bolivia miners protest". BBC News Online. February 7, 2007. Retrieved February 7, 2007.

- ^ Dorothy Kosich (7 February 2007). "20,000 miners march against Bolivia's ICM tax hike, concession policies". Retrieved on February 7, 2007.

- ^ Dan Keane (February 6, 2007). "Bolivian Miners Protest Tax Increase". Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved on February 6, 2007.

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum news, "New constitution outlined"

- ^ a b David Mercado (January 12, 2007). "Morales allies vow to step up protests in Bolivia". Reuters. Retrieved on January 31, 2007.

- ^ BIF Bulletin No 8 Santa Cruz and the banner of autonomy

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum News May 2008

- ^ UN Special Rapporteur preliminary report on Bolivia, April 2008

- ^ "Bolivia on alert over states' autonomy push". International Herald Tribune. 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ^ "Bolivia set on collision course over autonomy". Financial Times. 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum News Briefing

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum Briefing Bolivia constitution text sparks right-wing secession threat

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum - News

- ^ a b Bolivia Information Forum News Briefing May 2008

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum Bulletin Special Edition May 2008

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum News Briefing May 2008

- ^ "Bolivian president agrees to vote of confidence - CNN.com". CNN. May 8, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Bolivia Information Forum News Briefing May 2008

- ^ BIF Briefing February 2009

- ^ "Bolivia: after the vote", John Crabtree, Open Democracy, 2 February 2009

- ^ a b c Bolivia Information Forum News

- ^ The Irishman and the 'plot' to kill the Bolivian President

- ^ Prosecutor claims he has video of Dwyer discussing assassination

- ^ "Bolivian leader knocks industrial chicken, soda". Associated Press. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Evo Morales asegura que los hombres que comen pollo "de granja" se vuelven homosexuales". noticias24. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ http://www.digitalspy.com/odd/news/a216201/president-eating-chicken-causes-deviance.html

- ^ Evo Morales no pretendió atacar derechos de homosexuales: vocero, La Jornada, Martes 27 de abril de 2010

- ^ http://video.aol.com/video-detail/evo-morales-me-gusta-hacer-llorar-a-las-mujeres/1291190293%20-%2066k

- ^ http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo

- ^ http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo

- ^ http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo

- ^ http://www.eldeber.com.bo/anteriores/20011003/nacional_4.html

- ^ http://www.eldeber.com.bo/anteriores/20011003/nacional_4.html

- ^ http://www.tribunalconstitucional.gob.bo/resolucion9719.html

- ^ http://www.ernestojustiniano.org/foro/topic/evo-el-padre-modelo

External links

- www.evemorales.net - Information site about Morales and Bolivia

- Morales ‘Open Letter Regarding the European Union “Return Directive”, 2008

- Morales: I Believe Only In The Power Of The People

- Interview (on CounterPunch)

- Profile: Evo Morales, BBC News Online

- "Bolivia's Home-Grown President" Article in The Nation, (December 21, 2005).

- "'Evo Fashion' arrives in Bolivia", Morales's distinctive dress sense, on BBC News Online

- "Bolivia's first Indian president sworn in", Morales' inauguration ceremony on CNN's website

- "Direct Intervention: A Call for Bush and Bolivia’s Morales to Take a Leap of Faith and Change Presidential Issues into Personal Ones", From the Council on Hemispheric Affairs

- "Bolivian President Evo Morales on Latin America, U.S. Foreign Policy and the Role of the Indigenous People of Bolivia", Interview on Democracy Now!

- Bolivia: On the Road With Evo — The making of an unlikely president

- Bolivia Information Forum Information and background about Evo Morales and MAS party

- Evo Morales Interview with BBC

- Review of a speech Morales gave in NYC from PBS

- A Nobel Prize for Evo by Fidel Castro, Monthly Review, October 15, 2009

- Evo Morales on Climate Debt, Capitalism, & Why He Wants a Tribunal for Climate Justice - video report by Democracy Now!