Hamlet

Hamlet is a revenge tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is one of his best-known plays, one of the most-quoted works in the English language and universally included on lists of the world's greatest literature.[1] Critics have called Hamlet "Shakespeare's greatest play" and it is one of his most-performed, topping, for example, the Royal Shakespeare Company's list since 1879.[2] With 4,042 lines and 29,551 words, Hamlet is also Shakespeare's longest play.[3]

Hamlet is based on a Danish legend that Saxo Grammaticus recorded in his Gesta Danorum. François de Belleforest translated this legend into French in his Histoires Tragiques (1570). Shakespeare is thought to have borrowed much of his plot from a now-lost Elizabethan play that is referred to today as the Ur-Hamlet, which is the first version of the story known to have a ghost in it. Shakespeare's Hamlet also bears many similarities to Belleforest's French translation, but whether he took these elements directly from the French, or indirectly through the Ur-Hamlet or some other source, is unknown. Shakespeare wrote his play sometime between 1599 and 1601. Three different versions of Shakespeare's play have survived, which are known as the First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio, each of which have lines—and even scenes—missing from the others.

Many commentators on the play have wondered why Prince Hamlet, the play's protagonist, waits so long to exact revenge on Claudius for his father's murder. Some see his delay as a plot device—if he kills Claudius quickly, the plot is cut short. Others view it as a response to complex philosophical and ethical issues that constituted the idea of revenge in Shakespeare's day. Another common question is whether Hamlet becomes genuinely insane during the course of the play or whether he merely feigns his madness. Since Freud, psychoanalytic critics have probed Hamlet's unconscious desires, while feminist critics have called attention to Ophelia and Gertrude's experiences within the play.

Hamlet was one of Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime. Richard Burbage, the leading tragedian of the Lord Chamberlain's Men, first performed the role.[4] It was revived during the Restoration period and has been popular ever since. Several movie adaptations have been made, beginning with silent versions in the early 20th Century.

Sources

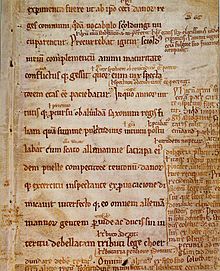

The story of the prince who plots revenge on his uncle, the current king, for killing his father, the former king, is an old one. Many of the story elements—the prince's feigned madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the testing of the prince's madness with a young woman, the prince talking to his mother and killing a hidden spy, his being sent to England with two retainers and substituting their execution for his own—are also part of a medieval tale by Saxo Grammaticus called Vita Amlethi (part of his larger Latin work Gesta Danorum), which was written around 1200 AD. Older written and oral traditions from various cultures influenced Saxo's work. Amleth, as Hamlet is called in his version, probably derived from an oral tale told throughout Scandinavia. Scholars have also uncovered references to it in Icelandic legend. Although there is no existing copy of the Icelandic version of the story, Torfaeus, an early Icelandic scholar (born 1636), described parallels to the Icelandic story of Amloi in the Spanish story of the Ambales Saga. This story contains similarities to Shakespeare's Hamlet in Prince Ambales' feigned madness, his accidental killing of the king's counsellor in his mother's bedroom, and the eventual slaying of his uncle.[5]

The two most popular candidates for written works that may have influenced Saxo, however, are the anonymous Scandinavian Saga of Hrolf Kraki and the Roman legend of Brutus, which is recorded in two separate Latin works. In Saga of Hrolf Kraki, there are two sons of the murdered king: Hroar and Helgi, who later take the names Ham and Hráni as a disguise. They spend most of the story in hiding, rather than feigning madness, though Ham does behave in a childlike manner to avoid suspicion at one point. The sequence of events differs from Shakespeare's as well. The Roman story of Brutus focuses on feigned madness, as a man called Lucius changes his name to Brutus ('dull, stupid') and plays the part in order to avoid the fate of his father and brothers. Eventually he slays his family's killer, King Tarquinus. In addition to writing in the Latin language of the Romans, Saxo adjusted the story to meet classical Roman concepts of virtue and heroism. A reasonably accurate version of Saxo's story was translated into French in 1570 by François de Belleforest in his Histoires Tragiques.[6] Belleforest embellished Saxo's text substantially, nearly doubling the total length. His version added descriptions of the hero's melancholy.[5]

Scholars have speculated about the ultimate source of the 'hero as fool' story, but no definitive candidate has emerged. Given the many different cultures from which Hamlet-like legends come (Roman, Spanish, Scandinavian and Arabic), a few have guessed that the story may be generally Indo-European in origin.[5]

Shakespeare's main source is believed to be an earlier play—now lost—known today as the Ur-Hamlet. Possibly written by Thomas Kyd, this earlier Hamlet play was in performance by 1589 and seems to have been the first to include a ghost in the story.[7] Shakespeare's company, the Chamberlain's Men, may have purchased that play and performed a version, which Shakespeare reworked, for some time.[5] Since no copy of the Ur-Hamlet has survived, however, it is impossible to compare its language and style with the known works of any candidate for its authorship; consequently, there is no direct evidence that Kyd wrote it, nor is there any evidence that the play was an early version by Shakespeare himself. This latter idea—that Shakespeare wrote Hamlet far earlier than the generally-accepted date and revised it on numerous occasions—has attracted some support, while others dismiss it as speculation.[8]

Scholars are unable to assert with any confidence how much material Shakespeare took from the Ur-Hamlet, how much from Belleforest or Saxo, and how much from other contemporary sources (such as Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy). There is no clear evidence that Shakespeare made any direct references to Saxo's version, although its Latin text was widely available at the time. There are, however, elements of Belleforest's version that appear in Shakespeare's play but not in Saxo's story. Whether Shakespeare took these from Belleforest directly or through the Ur-Hamlet remains unclear.[5]

It is clear, though, that several elements changed somewhere between Belleforest's and Shakespeare's versions. For one, unlike Saxo and Belleforest, Shakespeare's play has no all-knowing narrator, with the consequence that the audience is invited to draw its own conclusions about characters' motives. The traditional story also encompasses several years, while Shakespeare's covers a few weeks. Belleforest's version details Hamlet's plan for revenge, while in Shakespeare's play Hamlet has no apparent plan. Shakespeare also added some elements that located the action in 15th-century Christian Denmark, rather than a pagan, medieval setting. Elsinore, for example, would have been familiar to Elizabethan England, as a new castle had recently been built there, and Wittenberg, Hamlet's university, was widely known for its protestant teachings.[5] Other elements of Shakespeare's Hamlet that are not found in medieval versions include the secrecy that surrounds the old king's murder, the inclusion of Laertes and Fortinbras (who offer parallels to Hamlet), the testing of the king via a play, and Hamlet's tragic death at the moment he gains his revenge.[9]

Scholars have debunked the idea that Hamlet is in any way connected with Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet Shakespeare, who died at age eleven. Hamlet is too obviously connected to legend and the name Hamnet was quite popular at the time.[5]

Dating the play

The Register of the Stationers' Company records an entry for Hamlet on July 26, 1602, which indicates that the play was "latelie Acted by the Lo: Chamberleyne his servantes." This establishes a later limit for the dating of the play. Hamlet's frequent allusions to Julius Caesar, which has been dated to mid-1599, help to establish an earlier limit.[10] Edwards explains that, with reference to the exchanges between Hamlet and Polonius immediately before the play within a play (3.2.87–93):

Honigmann points out that it is usually assumed that John Heminges acted both the old-man parts, Caesar in the first play and Polonius in the second, and that Richard Burbage acted both Brutus and Hamlet. "Polonius would then be speaking on the extra-dramatic level in proclaiming his murder in the part of Caesar, since Hamlet (Burbage) will soon be killing him (Heminges) once more in Hamlet." There does indeed seem to be a kind of private joke here, with Heminges saying to Burbage "Here we go again!"[11]

The internal evidence of the "little eyases" that Rozencrantz mentions (2.2.315) is taken to refer to the War of the Theatres around 1601; this reference, though, is found only in the later folio text. Gabriel Harvey wrote a note in the margins of his copy of a 1598 edition of Chaucer's works that some scholars have used as evidence towards the play's dating; its evidence, however, is inconclusive. The note cites Hamlet as an example of a work by Shakespeare that "the wiser sort" enjoy as well as mentioning the Earl of Essex in a way that suggests that he was still alive. Since Essex was executed in February 1601 for rebellion, this would seem to suggest that the play was written before that date. The New Cambridge editor, however, dismisses this source; he argues that the "sense of time is so confused in Harvey's note that it is really of little use in trying to date Hamlet." This is because the same note also refers to Spenser and Watson as if they were still alive ("our flourishing metricians"), but also mentions "Owen's new epigrams", which were published in 1607.[12] In 1598, Francis Meres published his Palladis Tamia, which included a survey of English literature from Chaucer to its present day, within which a list of Shakespeare's plays appears; twelve are named, but Hamlet is not among them, suggesting that Shakespeare's play had not yet been written by that time. Shakespeare's Hamlet was very popular, Lott explains, so "it is unlikely that he [Meres] would have overlooked [...] so significant a piece."[13] Lott also refers to the internal evidence of the long exchange between Hamlet, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (2.2.326–345); this refers to the tour of the provinces on which the Globe company embarked in the autumn of 1601, he argues.[13] "Any dating of Hamlet must be tentative", Edwards cautions. Scholars date the play between 1599 and 1601.[14]

Early editions of the play

Several problems to interpreting the text are caused by differences between the three early printings of the play :[15]

- In 1603, the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell published the so-called "bad" first quarto (referred to as Q1); Valentine Simmes printed this edition. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later second quarto.

- In 1604, Nicholas Ling published the second quarto (referred to as Q2); James Roberts printed this edition. Some copies of Q2 are dated 1605, which may indicate a second impression; consequently, Q2 is often dated "1604/5". Q2 is the longest of the three editions, although it omits 85 lines that are found in F1 (these passages were most likely left out to avoid offending the queen of James I, who was from Denmark).[16]

- In 1623, Edward Blount and William and Isaac Jaggard published the First Folio (referred to as F1), the first edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works.[17]

Subsequent folios and quartos (John Smethwick's Q3, Q4, and Q5, 1611–37) are considered derivatives of these first three editions. Q1 itself has been viewed with scepticism; in practice, editors tend to rely upon Q2 and F1.[18]

Early editors of Shakespeare's works, beginning with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest sources of Hamlet then-known, Q2 and F1. Each text contains some material that the other lacks and there are many minor differences in wording—little more than 200 lines are identical in the two. Editors have tended to combine the two in an effort to create an "inclusive" text that is as close as possible to an imagined "ideal" of Shakespeare's original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time.[19] The "full text" approach that he established continues to influence editorial practice to the present day. Some contemporary scholarship, however, moves away from that approach towards a position that recognises that "an authentic Hamlet is an unrealisable ideal. [...] [T]here are texts of this play but no text."[20] The Arden Shakespeare series's 2006 publication of the different texts of Hamlet in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.[21]

Traditionally, editors of Shakespeare's plays have divided them into five acts. In the case of Hamlet, however, none of the early texts make that division; the organisation of the play into acts and scenes derives from a quarto that was first published in 1676. Modern editors generally follow this traditional division, but consider it unsatisfactory; there is an act-break at the point when Hamlet drags Polonius' body out of his mother's bedchamber between Act 3 Scene 4 and Act 4 Scene 1, after which the action appears to continue uninterrupted.[22]

The discovery in 1823 of Q1, whose existence had not even been suspected earlier, caused considerable interest and excitement and raised many questions of editorial practice and interpretation. Scholars identified apparent deficiencies of the text immediately—Q1 was instrumental in the development of the concept of a Shakespearean "bad quarto."[23] Yet Q1 also has value: it contains stage directions that reveal actual stage practices in a way that Q2 and F1 do not; it also contains an entire scene (usually labelled 4.6) that does not appear in either Q2 or F1; in addition, Q1 is useful for its comparison with the later editions. Q1 is generally thought to be a "memorial reconstruction" of the play as Shakespeare's company performed it, although there is disagreement whether the reconstruction was pirated or authorised. It is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1, apparently because of significant cuts for stage performance. It is thought that one of the actors who played a minor role (Marcellus, certainly, perhaps Voltemand as well) in the legitimate production was the source of this version.[24]

Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full-length play intended especially for travelling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular). Kathleen Irace develops this theory in her New Cambridge edition.[25] The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error but is rather a viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions; perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in Los Angeles, for which Irace herself served as dramaturge.[26] At least 28 different productions of the Q1 text since 1881 have demonstrated that it is eminently fit for the stage.

Characters

- Hamlet is the Prince of Denmark. Son to the late, and nephew to the present, king.

- Claudius is the King of Denmark, elected to the throne after the death of his brother, King Hamlet. Claudius has married Gertrude, his brother's widow.

- Gertrude is the Queen of Denmark, and King Hamlet's widow, now married to Claudius, and mother to Hamlet.

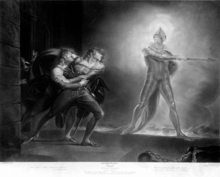

- The Ghost appears in the image of Hamlet's father, the late King Hamlet (Old Hamlet).

- Polonius is Claudius's chief advisor, and the father of Ophelia and Laertes. (This character is called "Corambis" in Q1.)

- Laertes is the son of Polonius, and has returned to Elsinore from Paris.

- Ophelia is Polonius' daughter, and Laertes' sister, who lives with her father at Elsinore.

- Horatio is a good friend of Hamlet, from the university at Wittenberg, who came to Elsinore Castle to attend King Hamlet's funeral.

- Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are childhood friends and schoolmates of Hamlet, who were summoned to Elsinore by Claudius and Gertrude.

- Marcellus, Barnardo, and Francisco are sentries who guard Elsinore Castle.

- Voltemand and Cornelius are ambassadors King Claudius sends to old King Norway.

- Reynaldo is Polonius's servant. (This character is called "Montano" in the First Quarto.)

- Players in a company of Players who arrive at Elsinore:

- First Player or Player King.

- Second Player or Player Queen, a lad.

- Third Player, Lucianus in "The Mousetrap" (or "The Murder of Gonzago")

- Fourth Player, the Prologue in "The Mousetrap" (or "The Murder of Gonzago")

- Fortinbras is the nephew of old King Norway. He is also the son of Fortinbras Sr., who was killed in single combat by Hamlet's father.

- A Captain in Fortinbras' army.

- A Gentleman who informs Gertrude of Ophelia's strange behaviour.

- Messengers

- Sailors (pirates).

- Two Clowns, a gravedigger and his companion.

- A Priest.

- Osric, a courtier (named "Ostricke" in Q2).

- English Ambassadors

- Yorick, a jester, is not a character, but his skull is unearthed by the gravedigger, and his memory is honoured by Hamlet.

- Lords, ladies, courtiers, servants, guards, officers, followers of Laertes, Norwegian soldiers.[27]

Synopsis

On a cold winter night, two sentries try to convince the sceptical student Horatio that they have seen the ghost of the recently-deceased King Hamlet, when the ghost suddenly appears. Horatio tries to question it but it stalks away. He proposes they tell the old king's son, Hamlet.

Claudius, the new king, proclaims an end to the official mourning for his brother, in light of his marriage to Gertrude, his brother's queen. Claudius and Gertrude try to persuade Hamlet to abandon his melancholy and not to return to university in Wittenberg. Hamlet promises to try to obey his mother. Left alone, he vents his frustration at her hasty remarriage. He is interrupted by Horatio and the sentries, who inform him of the portentous apparition.

That night, Hamlet speaks to his father's ghost, who reveals that he was poisoned by Claudius. He commands Hamlet to avenge his murder. Hamlet vows to do so and swears his companions to secrecy. He decides to disguise his true intents by feigning madness.

Ophelia reports to her father, the King's counsellor Polonius, how Hamlet came to her bedroom in a fit of madness. Polonius deduces an "ecstasy of love" is to blame. Meanwhile, Claudius enlists two of Hamlet's school-friends, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, to discover the cause of Hamlet's madness. Polonius puts his theory to Claudius and Gertrude.

Hamlet greets Rozencrantz and Guildenstern warmly, but soon discerns their duplicity. He professes disaffection with the world, for which Rozencrantz recommends a troupe of actors, who soon arrive. Hamlet solicits a passionate performance from one of them. Alone, he reflects on the feigned passion of the actor and his own failure to act. Uncertain whether the ghost was genuine, he resolves to confirm his uncle's guilt by observing his response to the staging of a play, which he later calls The Mousetrap.

Claudius agrees to attend the play, but first he and Polonius hide themselves, to spy on Hamlet with Ophelia. Thinking he is alone, Hamlet reflects on his predicament, until Ophelia alerts him to her presence. Hamlet berates her for her immodesty and dismisses her to a nunnery, causing her great distress. The king decides to send Hamlet to England, but Polonius persuades him first to allow the Queen to try to discover the cause of Hamlet's distemper.

Hamlet directs the actors' preparations. The court assembles and the play begins; Hamlet offers a running commentary throughout. When the action shows a king poisoned, Claudius rises abruptly and leaves, from which Hamlet deduces his guilt.

Hamlet is summoned to his mother's bedchamber. On his way, he discovers Claudius praying. Poised to kill, Hamlet hesitates, reasoning that to kill Claudius in prayer would send him to heaven.

Hamlet confronts his mother in her chamber. Gertrude panics and cries out. Polonius, hiding behind a tapestry, responds, prompting Hamlet to stab wildly in that direction. Hoping it was the king, he discovers Polonius' corpse. Hamlet directs a sustained accusation at Gertrude, who admits some guilt. The ghost appears to bid him treat her gently and to spur him on to his revenge. Unable to see the apparition, Gertrude takes Hamlet's behaviour for a sign of madness. Hamlet drags the corpse away.

Claudius sends Hamlet to England with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, who carry a secret request for his execution. Having watched the army of Fortinbras (nephew to the Norwegian king) pass through, Hamlet reflects on his own inaction.

Ophelia wanders the court in grief-induced madness, singing incoherently. Laertes (Polonius’s son recently returned from abroad), seeking revenge for his father's murder, bursts into the royal chamber at the head of a rabble that clamours for him to be king. The sight of his sister, Ophelia, in her distracted state further incenses him. Claudius convinces Laertes that Hamlet is to blame. Learning of Hamlet's escape and return to Denmark, Claudius proposes a rigged fencing-match, using poisoned rapiers, as a surreptitious vehicle for Laertes' revenge. Gertrude interrupts to report that Ophelia has drowned.

Two clowns debate the legality of Ophelia's apparent suicide, whilst digging her grave. Hamlet arrives with Horatio and banters with a gravedigger, who unearths the skull of a jester from Hamlet's childhood, Yorick. A funeral procession approaches. On hearing that it is Ophelia's and seeing Laertes leap into her grave, Hamlet advances and the two grapple.

Back at Elsinore, Hamlet tells Horatio the story of his escape and how he arranged the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. A courtier informs Hamlet of the king's wager on a fencing match with Laertes. Hamlet agrees to participate.

The court enters, ready for the match. Claudius orders cups of wine prepared, one of which he has poisoned. During the bout, Gertrude drinks from the poisoned cup. Laertes succeeds in piercing Hamlet with a poisoned blade, but, in the struggle, is wounded by it himself. Gertrude dies. With his dying breath, Laertes reveals the king’s plot. Hamlet kills Claudius. Hamlet and Laertes forgive each other as Laertes dies. Before succumbing to the poison, Hamlet names Fortinbras as heir. As Fortinbras arrives, Horatio promises to recount the tale. Fortinbras orders Hamlet’s body borne off in honour.

Analysis and criticism

Critical history

From the beginning, Hamlet has prompted questions from critics regarding Hamlet's supposed madness and melancholy. Critics in Shakespeare's day focused on these themes in their understanding of the play; these aspects were portrayed more violently than they would come to be in subsequent times.[28] During the Restoration period, critics disapproved of the play's lack of unity in time and space, as well as the perceived immodesty of Ophelia's madness in the flower scene.[29] Views of the play improved, however, in the 18th century. Critics came to regard Hamlet as a hero—a pure, brilliant young man thrust into unfortunate circumstances.[30] Psychological and mystical readings increased with the rise of Gothic literature in this period. Hamlet's madness and the ghost both attracted significant attention.[31] The Romantic period viewed Hamlet as the epitome of a tragic fall.[32] 19th-century critics focused on Hamlet's individual drive and internal struggle; he came to be regarded as a political rebel and intellectual rather than an over-sensitive melancholic. This period also introduced questions as to why Hamlet delays in killing the king, which critics of earlier periods had largely ignored as a mere plot device.[30] In the 20th century, criticism branched in several directions. Ernest Jones developed Sigmund Freud's suggestion that Hamlet had an unresolved Oedipus complex, while feminist critics introduced new points of view towards Gertrude and Ophelia. New Historicist and cultural materialist critics have examined the play in its historical context, attempting to piece together the cultural environment within which the play existed.[30]

Dramatic structure

In creating Hamlet, Shakespeare broke several rules, one of the largest being the rule of action over character. In his day, plays were usually expected to follow the advice of Aristotle in his Poetics, which declared that a drama should not focus on character so much as action. The highlights of Hamlet, however, are not the action scenes, but the soliloquies, wherein Hamlet reveals his motives and thoughts to the audience. Also, unlike Shakespeare's other plays, there is no strong subplot; all plot forks are directly connected to the main vein of Hamlet struggling to gain revenge. The play is full of seeming discontinuities and irregularities of action. At one point, Hamlet is resolved to kill Claudius: in the next scene, he is suddenly tame. Scholars still debate whether these odd plot turns are mistakes or intentional additions to add to the play's theme of confusion and duality.[33]

Language

Much of the play's language is in the elaborate, witty discourse expected in a royal court. This is in line with Baldassare Castiglione's work, The Courtier (published in 1528), which outlines several courtly rules, specifically advising servants of royals to amuse their rulers with their inventive language. Osric and Polonius seem, especially, to respect this suggestion. Claudius' speech is full of rhetorical figures, as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's, while Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers use simpler methods of speech. Claudius demonstrates an authoritative control over the language of a King, referring to himself in the first person plural ("we" or "us"), and using anaphora mixed with metaphor that hearkens back to Greek political speeches. Hamlet seems the most educated in rhetoric of all the characters, using anaphora, as the king does, but also asyndeton and highly developed metaphors, while at the same time managing to be precise and unflowery (as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother, saying "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe."). His language is very self-conscious, and relies heavily on puns. Especially when pretending to be mad, Hamlet uses puns to reveal his true thoughts while at the same time hiding them. Psychologists have since associated a heavy use of puns with schizophrenia.[34]

Hendiadys is one rhetorical type found in several places in the play, as in Ophelia's speech after the nunnery scene ("Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state" and "I, of all ladies, most deject and wretched" are two examples). Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. Hamlet was written later in his life, when he was better at matching rhetorical figures with the characters and the plot than early in his career. Wright, however, has proposed that hendiadys is used to heighten the sense of duality in the play.[35]

Hamlet's soliloquies have captured the attention of scholars as well. Early critics viewed such speeches as To be or not to be as Shakespeare's expressions of his own personal beliefs. Later scholars, such as Charney, have rejected this theory saying the soliloquies are expressions of Hamlet's thought process. During his speeches, Hamlet interrupts himself, expressing either disgust or agreement with himself, and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly, and instead skirts around the basic idea of his thought. Not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, is Hamlet really able to be direct and sure in his speech.[36]

Contexts

Religious

The play makes several references to both Catholicism and Protestantism, the two most powerful theological forces of the time in Europe. The Ghost describes himself as being in purgatory, and as having died without receiving his last rites. This, along with Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is uniquely Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have pointed that revenge tragedies were traditionally Catholic, possibly because of their sources: Spain and Italy, both Catholic nations. Scholars have pointed out that knowledge of the play's Catholicism can reveal important paradoxes in Hamlet's decision process. According to Catholic doctrine, the strongest duty is to God and family. Hamlet's father being killed and calling for revenge thus offers a contradiction: does he avenge his father and kill Claudius, or does he leave the vengeance to God, as his religion requires?[37]

The play's Protestantism lies in its location in Denmark, a Protestant country in Shakespeare's day, though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to mirror this fact. The play does mention Wittenburg, which is where Hamlet is attending university, and where Martin Luther first nailed his 95 theses.[38] One of the more famous lines in the play related to Protestantism is: "There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be not now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet will it come—the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is't to leave betimes, let be."[39]

In the First Quarto, the same line reads: “There's a predestinate providence in the fall of a sparrow." Scholars have wondered whether Shakespeare was censored, as the word “predestined” appears in this one Quarto of Hamlet, but not in others, and as censoring of plays was far from unusual at the time.[40] Rulers and religious leaders feared that the doctrine of predestination would lead people to excuse the most traitorous of actions, with the excuse, “God made me do it.” English Puritans, for example, believed that conscience was a more powerful force than the law, due to the new ideas at the time that conscience came not from religious or government leaders, but from God directly to the individual. Many leaders at the time condemned the doctrine, as: “unfit 'to keepe subjects in obedience to their sovereigns” as people might “openly maintayne that God hath as well pre-destinated men to be trayters as to be kings."[41] King James, as well, often wrote about his dislike of Protestant leaders' taste for standing up to kings, seeing it as a dangerous trouble to society.[42] Throughout the play, Shakespeare mixes the two religions, making interpretation difficult. At one moment, the play is Catholic and medieval, in the next, it is logical and Protestant. Scholars continue to debate what part religion and religious contexts play in Hamlet.[43]

Philosophical

Hamlet is often perceived as a philosophical character. Some of the most prominent philosophical theories in Hamlet are relativism, existentialism, and scepticism. Hamlet expresses a relativist idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so" (2.2.239–240). The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek Sophists, who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses, and all men felt and sensed things differently, truth was entirely relative. There was no absolute truth.[44] This same line of Hamlet's also introduces theories of existentialism. A double-meaning can be read into the word "is", which introduces the question of whether anything "is" or can be if thinking doesn't make it so. This is tied into his To be, or not to be speech, where "to be" can be read as a question of existence. Hamlet's contemplation on suicide in this scene, however, is more religious than philosophical. He believes that he will continue to exist after death.[45]

Hamlet is perhaps most affected by the prevailing scepticism in Shakespeare's day in response to the Renaissance's humanism. Humanists living prior to Shakespeare's time had argued that man was godlike, capable of anything. They argued that man was the God's greatest creation. Scepticism toward this attitude is clearly expressed in Hamlet's What a piece of work is a man speech:[46]

... this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man—how noble in reason; how infinite in faculties, in form and moving; how express and admirable in action; how like an angel in apprehension; how like a god; the beauty of the world; the paragon of animals. And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? (Q2, 2.2.264–274)[47]

Scholars have pointed out this section's similarities to lines written by Michel de Montaigne in his Essais:

Who have persuaded [man] that this admirable moving of heavens vaults, that the eternal light of these lampes so fiercely rowling over his head, that the horror-moving and continuall motion of this infinite vaste ocean were established, and contine so many ages for his commoditie and service? Is it possible to imagine so ridiculous as this miserable and wretched creature, which is not so much as master of himselfe, exposed and subject to offences of all things, and yet dareth call himself Master and Emperor.

Rather than being a direct influence on Shakespeare, however, Montaigne may have been reacting to the same general atmosphere of the time, making the source of these lines one of context rather than direct influence.[48]

Political

Political satire resulted in the punishment of many notable playwrights for plays deemed "offensive" during this period: Ben Jonson was jailed for his participation in The Isle of Dogs and it is thought that Thomas Middleton was banned from writing for the stage after the Privy Council closed his A Game of Chess after nine performances.[49] Shakespeare was not censured in this way, though some have conjectured that in Hamlet, through the character of Polonius, he satirised William Cecil (Lord Burghley), Lord High Treasurer and chief counsellor to Queen Elizabeth.[50]

Several parallels have been drawn between the two, including: that Polonius's role as counsellor might be said to stand in the same relation to the monarch as Burghley's role to Elizabeth had done in the past;[51] that Polonius' precepts to Laertes may echo Burghley's private precepts to his son Robert Cecil;[52] that Polonius's tedious verbosity may resemble Burghley's verbal patterns;[53] that "Corambis," the form in which the character's name appears in Q1, resembles the Latin for "double-hearted"—which may satirise Lord Burghley's Latin motto Cor unum, via una ("One heart, one way");[54] that Polonius's daughter Ophelia's relationship with Hamlet may be compared to Burghley's daughter Anne Cecil's relationship with the Earl of Oxford, Edward de Vere.[55] These arguments have, in the most part, been offered to support the authorship claims for the Earl of Oxford.[56]

Far from being suppressed, Hamlet was given the royal seal of approval, as the appearance of the royal arms on the frontispiece of the 1604 Hamlet printed by James Roberts indicates.[57]

Other interpretations

Psychoanalytic

Two of the intellectual giants of psychoanalysis—Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan—have offered interpretations of Hamlet.[58] In his The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud proceeds from his recognition of what he perceives to be a fundamental contradiction in the text: "the play is built up on Hamlet's hesitations over fulfilling the task of revenge that is assigned to him; but its text offers no reasons or motives for these hesitations".[59] He considers Goethe's 'paralysis from over-intellectualization' explanation as well as the idea that Hamlet is a "pathologically irresolute character". He rejects both, citing the evidence that the play presents of Hamlet's ability to take action: his impulsive murder of Polonius and his Machiavellian murder of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Instead, Freud argues, Hamlet's inhibition against taking vengeance on Claudius has an unconscious origin.

In an anticipation of his later theories of the Oedipus complex, Freud suggests that Claudius has shown Hamlet "the repressed wishes of his own childhood realised" (his desire to kill his father and take his father's place with his mother). Confronted with this image of his own repressed desires, Hamlet responds with "self-reproaches" and "scruples of conscience, which remind him that he himself is literally no better than the sinner whom he is to punish."[59] Freud goes on to suggest that Hamlet's apparent "distaste for sexuality", as expressed in his conversation with Ophelia (presumably in the 'nunnery scene' rather than during the play-within-a-play), "fits in well" with this interpretation.[60]

Following Freud's suggestion, the Welsh psychoanalyst Ernest Jones developed these ideas in a series of essays that culminated in his book Hamlet and Oedipus (1949). Under the influence of these psychoanalytic explorations, several productions have portrayed the 'closet scene', in which Hamlet confronts his mother in her private quarters, in a sexual light. In this reading, Hamlet scolds his mother for her sexual relationship with Claudius while simultaneously wishing (unconsciously) that he could take Claudius' place; adultery and incest are what he simultaneously loves and hates about his mother. Ophelia's madness after her father's death may be read through the Freudian lens as a reaction to the death of her hoped-for lover, her father. Her unrequited love for him suddenly slain is too much for her and she drifts into insanity.[61]

In addition to the brief psychoanalysis of Hamlet, Freud offers a correlation with Shakespeare's own life: Hamlet was written in the wake of the death of his father (in 1601), which revived his own repressed childhood wishes; Freud also points to the identity of Shakespeare's dead son Hamnet and the name 'Hamlet'. "Just as Hamlet deals with the relation of a son to his parents," Freud concludes, "so Macbeth (written at approximately the same period) is concerned with the subject of childlessness." Having made these suggestions, however, Freud offers a caveat: he has unpacked only one of the many motives and impulses operating in the author's mind, albeit, Freud claims, one that operates from "the deepest layer".[60]

Later in the same book, having used psychoanalysis to explain Hamlet, Freud uses Hamlet to explain the nature of dreams: in disguising himself as a madman and adopting the license of the fool, Hamlet "was behaving just as dreams do in reality [...] concealing the true circumstances under a cloak of wit and unintelligibility". When we sleep, each of us adopts Hamlet's "antic disposition".[62]

Feminist

Feminist critics have focused on the gender system of early modern England. For example, they point to the common classification of women as maid, wife or widow, with only whores outside this trilogy. Using this analysis, the problem of Hamlet becomes the central character's identification of his mother as a whore due to her failure to remain faithful to Old Hamlet, in consequence of which he loses his faith in all women, treating Ophelia as if she were a whore also.[63]

Carolyn Heilbrun published an essay on Hamlet in 1957 entitled "Hamlet's Mother". In it, she defended Gertrude, arguing that the text never hints that Gertrude knew of Claudius poisoning King Hamlet. This view has been championed by many feminists. Heilbrun argued that the men who had interpreted the play over the centuries had completely misinterpreted Gertrude, believing what Hamlet said about her rather than the actual text of the play. In this view, no clear evidence suggests that Gertrude was an adulteress. She was merely adapting to the circumstances of her husband's death for the good of the kingdom.[64]

Ophelia, also, has been defended by feminists, most notably Elaine Showalter.[65] Ophelia is surrounded by powerful men: her father, brother, and Hamlet. All three disappear: Laertes leaves, Hamlet abandons her, and Polonius dies. Conventional theories had argued that without these three powerful men making decisions for her, Ophelia was driven into madness.[66] Feminist theorists argue that she goes mad with guilt because, when Hamlet kills her father, he has fulfilled her sexual desire to have Hamlet kill her father so they can be together. Showalter points out that Ophelia has become the symbol of the distraught and hysterical woman in modern culture, a symbol which may not be entirely accurate nor healthy for women.[67]

Performance history

Shakespeare's day to the Interregnum

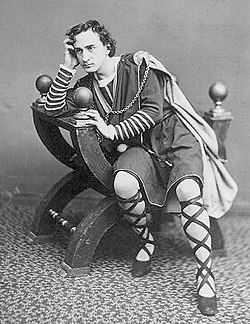

Shakespeare wrote the role of Hamlet for Richard Burbage, who was the chief tragedian of the Lord Chamberlain's Men and an actor with a capacious memory for lines and a wide emotional range.[4] Hamlet appears to have been Shakespeare's fourth most popular play during his lifetime—only Henry VI Part 1, Richard III and Pericles eclipsed it.[68] Shakespeare does not provide a firm indication of when his play is set, but, following the theatrical conventions of the time, the play would have been performed at the Globe in Elizabethan dress.[69]

Firm evidence for specific performances of the play is scant. Hamlet had toured in Germany within five years of Shakespeare's death.[70] The crew of the ship Dragon, off Sierra Leone, performed Hamlet in September 1607.[71] Shakespeare's company performed the play before James I in 1619 and Charles I in 1637, the latter on January 24 at Hampton Court Palace.[72] Hibbard argues that, since Hamlet is second only to Falstaff among Shakespeare's characters in the number of allusions and references in the literature of the period, the play must have been performed with a frequency that the historical record misses.[73]

Restoration and 18th century

The play was revived early in the Restoration era: in the division of existing plays between the two patent companies, Hamlet was the only Shakespearean favourite that Sir William Davenant's Duke's Company secured.[74] Davenant cast Thomas Betterton in the central role, who would continue to pay Hamlet until he was 74.[75] David Garrick at Drury Lane produced a version that adapted Shakespeare heavily; he declared: "I had sworn I would not leave the stage till I had rescued that noble play from all the rubbish of the fifth act. I have brought it forth without the grave-digger's trick, Osrick, & the fencing match."[76] The first actor known to have played Hamlet in North America is Lewis Hallam, Jr. in the American Company's production in Philadelphia in 1759.[77]

John Philip Kemble made his Drury Lane debut as Hamlet, in 1783.[78] His performance was said to be twenty minutes longer than anyone else's and his lengthy pauses led to the cruel suggestion that "music should be played between the words."[79] Sarah Siddons is the first actress known to have played Hamlet; many women have played Hamlet as a breeches role since, to great acclaim.[80] In 1748, Alexander Sumarokov wrote a Russian adaptation that focused on Prince Hamlet as the embodiment of an opposition to Claudius' tyranny—a recurrent treatment that would pervade Eastern European adaptations into the twentieth century.[81] In the years following America's independence, Thomas Abthorpe Cooper was the young nation's leading tragedian, performing Hamlet (among other plays) at the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia and the Park Theatre in New York. Although chided for "acknowledging acquaintances in the audience" and "inadequate memorisation of his lines", he became a national celebrity.[82]

19th century

In the romantic and early Victorian eras, leading London actors on tour provided the highest-quality Shakespearean performances in the United States, including George Frederick Cooke, Junius Brutus Booth, Edmund Kean, William Charles Macready and Charles Kemble. Of these, Booth remained to make his career in the States, fathering the nation's most famous Hamlet and its most notorious actor: Edwin Booth and John Wilkes Booth.[83] Charles Kemble initiated an enthusiasm for Shakespeare in the French: leading members of the Romantic Movement saw his 1827 Paris performance of Hamlet, including Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas, who particularly admired Harriet Smithson's performance of Ophelia in the mad scenes.[84] Edmund Kean was the first Hamlet to abandon the regal finery usually associated with the role in favour of a plain costume and the first to play Hamlet as serious and introspective.[85] The actor-managers of the Victorian era (including Kean, Phelps, Macready and Irving) staged Shakespeare in a grand manner, with elaborate scenery and costumes.[86] In stark contrast, William Poel's production of the first quarto text in 1881 was an early attempt at reconstructing Elizabethan theatre conditions; he set the play against red curtains.[87]

The tendency of the actor-managers to emphasise the importance of their own central character did not always meet with the critics' approval. Shaw's praise for Forbes-Robertson's performance ends with a sideswipe at Irving: "The story of the play was perfectly intelligible, and quite took the attention of the audience off the principal actor at moments. What is the Lyceum coming to?"[88] By the middle of the nineteenth century Hamlet had become so assimilated into German culture that Ferdinand Freiligrath declared that "Germany is Hamlet"[89] From the 1850s in India, the Parsi theatre tradition transformed Hamlet into folk performances, with dozens of songs added.[90] In the United States, Edwin Booth's Hamlet became a theatrical legend. He was described as "like the dark, mad, dreamy, mysterious hero of a poem... [acted] in an ideal manner, as far removed as possible from the plane of actual life."[91] Booth played Hamlet for 100 nights in the 1864/5 season at the Winter Garden Theatre, inaugurating the era of long-run Shakespeare in America.[92] Sarah Bernhardt played the prince in her popular 1899 London production. In contrast to the "effeminate" view of the central character that usually accompanied a female casting, she described her character as "manly and resolute, but nonetheless thoughtful... [he] thinks before he acts, a trait indicative of great strength and great spiritual power."[93]

20th century

Apart from some western troupes' 19th-century visits, the first professional performance of Hamlet in Japan was Otojiro Kawakami's 1903 Shimpa ("new school theatre") adaptation.[94] Shoyo Tsubouchi translated Hamlet and produced a performance in 1911 that blended Shingeki ("new drama") and Kabuki styles.[95] This hybrid-genre reached its peak in Fukuda Tsuneari's 1955 Hamlet.[96] In 1998, Yukio Ninagawa produced an acclaimed version of Hamlet in the style of Nō theatre, which he took to London.[97]

Constantin Stanislavski and Edward Gordon Craig—two of the 20th century's most influential theatre practitioners—collaborated on the Moscow Art Theatre's seminal production of 1911–12.[98] While Craig favoured stylised abstraction, Stanislavski, armed with his 'system', explored psychological motivation.[99] Craig conceived of the play as a symbolist monodrama, offering a dream-like vision as seen through Hamlet's eyes alone.[100] This was most evident in the staging of the first court scene (1.2).[101] The most famous aspect of the production is Craig's use of large, abstract screens that altered the size and shape of the acting area for each scene, representing the character's state of mind spatially or visualising a dramaturgical progression.[102] The production attracted enthusiastic and unprecedented worldwide attention for the theatre and placed it "on the cultural map for Western Europe."[103]

Hamlet is often played with contemporary political overtones: Leopold Jessner's 1926 production at the Berlin Staatstheater portrayed Claudius' court as a parody of the corrupt and fawning court of Kaiser Wilhelm.[104] Hamlet is also a psychological play: John Barrymore introduced Freudian overtones into the closet scene and mad scene of his landmark 1922 production in New York, which ran for 101 nights (breaking Booth's record). He took the production to the Haymarket in London in 1925 and it greatly influenced subsequent performances by John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier.[105] Gielgud played the central role many times: his 1936 New York production ran for 136 performances, leading to the accolade that he was "the finest interpreter of the role since Barrymore."[106] Although "posterity has treated Maurice Evans less kindly", throughout the 1930s and 1940s it was he, not Gielgud or Olivier, who was regarded as the leading interpreter of Shakespeare in the United States and in the 1938/9 season he presented Broadway's first uncut Hamlet, running four and a half hours.[107]

In 1937, Tyrone Guthrie directed Olivier in a Hamlet at the Old Vic based on psychoanalyst Ernest Jones' "Oedipus complex" theory of Hamlet's behaviour.[108] Olivier was involved in another landmark production, directing Peter O'Toole as Hamlet in the inaugural performance of the newly-formed National Theatre, in 1963.[109]

In Poland, the number of productions of Hamlet has tended to increase at times of political unrest, since its political themes (suspected crimes, coups, surveillance) can be used to comment on a contemporary situation.[110] Similarly, Czech directors have used the play at times of occupation: a 1941 Vinohrady Theatre production "emphasised, with due caution, the helpless situation of an intellectual attempting to endure in a ruthless environment."[111] In China, performances of Hamlet often have political significance: Gu Wuwei's 1916 The Usurper of State Power, an amalgam of Hamlet and Macbeth, was an attack on Yuan Shikai's attempt to overthrow the republic.[112] In 1942, Jiao Juyin directed the play in a Confucian temple in Sichuan Province, to which the government had retreated from the advancing Japanese.[113] In the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the protests at Tiananmen Square, Lin Zhaohua staged a 1990 Hamlet in which the prince was an ordinary individual tortured by a loss of meaning. In this production, the actors playing Hamlet, Claudius and Polonius exchanged roles at crucial moments in the performance, including the moment of Claudius' death, at which point the actor mainly associated with Hamlet fell to the ground.[114]

Screen performances

The earliest screen success for Hamlet was Sarah Bernhardt's five-minute film of the fencing scene, in 1900. The film was a crude talkie, in that music and words were recorded on phonograph records, to be played along with the film.[115] Silent versions were released in 1907, 1908, 1910, 1913 and 1917.[116] In 1920, Asta Nielsen played Hamlet as a woman who spends her life disguised as a man.[117] Laurence Olivier's 1948 film noir feature won best picture and best actor Oscars. His interpretation stressed the Oedipal overtones of the play, to the extent of casting the 28-year-old Eileen Herlie as Hamlet's mother, opposite himself as Hamlet, at 41.[118] Gamlet ([Гамлет] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a 1964 film adaptation in Russian, based on a translation by Boris Pasternak and directed by Grigori Kozintsev, with a score by Dmitri Shostakovich.[119] John Gielgud directed Richard Burton at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre in 1964–5, and a film of a live performance was produced, in ELECTRONOVISION.[120] Franco Zeffirelli's Shakespeare films have been described as "sensual rather than cerebral": his aim to make Shakespeare "even more popular".[121] To this end, he cast the Australian actor Mel Gibson—then famous as Mad Max—in the title role of his 1990 version, and Glenn Close—then famous as the psychotic other woman in Fatal Attraction—as Gertrude.[122]

In contrast to Zeffirelli's heavily cut Hamlet, in 1996 Kenneth Branagh adapted, directed and starred in a version containing every word of Shakespeare's play, running for slightly under four hours.[123] Branagh set the film with Victorian era costuming and furnishings; and Blenheim Palace, built in the early 18th century, became Elsinore Castle in the external scenes. The film is structured as an epic and makes frequent use of flashbacks to highlight elements not made explicit in the play: Hamlet's sexual relationship with Kate Winslet's Ophelia, for example, or his childhood affection for Ken Dodd's Yorick.[124] In 2000, Michael Almereyda set the story in contemporary Manhattan, with Ethan Hawke playing Hamlet as a film student. Claudius became the CEO of "Denmark Corporation", having taken over the company by killing his brother.[125]

Adaptations

Hamlet has been adapted into stories that deal with civil corruption by the West German director Helmut Käutner in Der Rest is Schweigen (The Rest is Silence) and by the Japanese director Akira Kurosawa in Warui Yatsu Hodo Yoku Nemeru (The Bad Sleep Well).[126] In Claude Chabrol's Ophélia (France, 1962) the central character, Yvan, watches Olivier's Hamlet and convinces himself—wrongly and with tragic results—that he is in Hamlet's situation.[127] In 1977, East German playwright Heiner Müller wrote Die Hamletmaschine (Hamletmachine) a postmodernist, condensed version of Hamlet; this adaptation was subsequently incorporated into his translation of Shakespeare's play in his 1989/1990 production Hamlet/Maschine (Hamlet/Machine).[128] Tom Stoppard directed a 1990 film version of his own play Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead.[129] The highest-grossing Hamlet adaptation to-date is Disney's Academy Award-winning animated feature The Lion King: although, as befits the genre, the play's tragic ending is avoided.[130] In addition to these adaptations, there are innumerable references to Hamlet in other works of art.

References

Footnotes

- ^ Hamlet has 208 quotations in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations; it takes up 10 of 85 pages dedicated to Shakespeare in the 1986 Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (14th ed. 1968). For examples of lists of the greatest books, see Harvard Classics, Great Books, Great Books of the Western World, Harold Bloom's The Western Canon, St. John's College reading list, and Columbia College Core Curriculum.

- ^ See Shapiro (2005) and Crystal and Crystal (2005, 66).

- ^ Based on the length of the first edition of The Riverside Shakespeare (1974).

- ^ a b See Taylor (2002, 4); Banham (1998, 141); Hattaway asserts that "Richard Burbage [...] played Hieronimo and also Richard III but then was the first Hamlet, Lear, and Othello" (1982, 91); Peter Thomson argues that the identity of Hamlet as Burbage is built into the dramaturgy of several moments of the play: "we will profoundly misjudge the position if we do not recognise that, whilst this is Hamlet talking about the groundlings, it is also Burbage talking to the groundlings" (1983, 24); see also Thomson on the first player's beard (1983, 110). A researcher at the British Library feels able to assert only that Burbage "probably" played Hamlet; see its page on Hamlet.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saxo and William Hansen (1983).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 1–2).

- ^ Jenkins (1982, 82–5).

- ^ In his 1936 book The Problem of Hamlet: A Solution Andrew Carincross asserted that the Hamlet referred to in 1589 was written by Shakespeare; Peter Alexander (1964), Eric Sams (according to Jackson 1991, 267) and, more recently, Harold Bloom (2001, xiii and 383; 2003, 154) have agreed. It is an opinion that is also held by anti-Stratfordians (Ogburn 1988, 631). Harold Jenkins, the editor of the second series Arden edition of the play, dismisses the idea as groundless (1982, 84 n4). Francis Meres's Palladis Tamia (published in 1598, probably October) provides a list of Shakespeare's plays in which twelve are named, but Hamlet is not among them (Lott 1970, xlvi).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 2). See Jenkins for a detailed discussion of many possible influences that may have found their way into the play (1982, 82–122).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 12–13) and Edwards (1985, 5–6).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 5).

- ^ Edwards (1985, 5).

- ^ a b Lott (1970, xlvi).

- ^ James Shapiro offers 1599 (2005); the editor of the New Cambridge edition settles on mid-1601 (Edwards 1985, 8); the editor of the New Swan Shakespeare Advanced Series edition agrees with 1601 (Lott 1970, xlvi);

- ^ Chambers (1923 vol. 3, 486–7) and Halliday (1964, 204–5).

- ^ Halliday (1964, 204).

- ^ Greg (1955).

- ^ Jenkins (1955) and Wilson (1934).

- ^ Hibbard (1987, 22–3).

- ^ Hattaway 1987, 16).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor published the Second Quarto text, with appendices, in its first volume (2006a) and the Folio and First Quarto texts in its second volume (2006b). Bate and Rasmussen (2007) is an edition of the Folio text with the additional passages from the Second Quarto in an appendix. The New Cambridge series has begun to publish separate volumes for the quarto versions that exist of Shakespeare's plays (Irace 1998).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006a, 543–552).

- ^ Jenkins (1982, 14).

- ^ Duthie (1941).

- ^ Irace (1998).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006b, 17).

- ^ Character list collated from Spencer (1980, 61–2); Thomson & Taylor (2006a, 140)

- ^ Wofford (1994) and Kirsch (1968).

- ^ Vickers (1974a, 447) and (1974b, 92).

- ^ a b c Wofford (1994).

- ^ Vickers (1974c, 5).

- ^ Rosenberg (1992, 179).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 67–72, 84).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 84–85; 89–90).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 87–88).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 91–93).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 37–38); in the New Testament, see Romans 12:19: "'vengeance is mine, I will repay' sayeth the Lord".

- ^ MacCary (1998, 38).

- ^ Hamlet (5.2.202–206).

- ^ Blits (2001, 3–21).

- ^ Matheson (1995).

- ^ Ward (1992).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 37–45).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 47–48).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 28–49).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 49).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006, 256–7)

- ^ Knowles (1999) and MacCary (1998, 49).

- ^ See Patterson (1984) and Marcus (1988).

- ^ French writes in 1869: "The next important personages in the play are the 'Lord Chamberlain,' Polonius; his son, Laertes; and daughter, Ophelia; and these are supposed to stand for Queen Elizabeth's celebrated Lord High Treasurer, Sir William Cecil, Lord Burleigh; his second son, Robert Cecil; and his daughter, Anne Cecil" (301). Excepts from his speculations may be found here. In 1932, John Dover Wilson wrote: "the figure of Polonius is almost without doubt intended as a caricature of Burleigh, who died on August 4, 1598" (1932, 104).

- ^ Winstanley (1921, 112). Winstanley devotes 20 pages to his proposals for connections between scenes involving Polonius and people and events in Elizabethan England.

- ^ See Chambers (1930, 418); in 1964, Hurstfield and Sutherland wrote: "The governing classes were both paternalistic and patronizing; and nowhere is this attitude better displayed than in the advice which that archetype of elder statesmen William Cecil, Lord Burghley—Shakespeare's Polonius—prepared for his son" (1964, 35).

- ^ Rowse (1963, 323).

- ^ Ogburn (1988, 202–203). As glossed by Mark Anderson, "With 'cor' meaning 'heart' and with 'bis' or 'ambis' meaning 'twice' or 'double', Corambis can be taken for the Latin of 'double-hearted,' which implies 'deceitful' or 'two-faced'."

- ^ Winstanley (1921, 122–124).

- ^ Ogburn (1988).

- ^ Matus (1994, 234–237).

- ^ See Lacan (1959) and Showalter (1985).

- ^ a b Freud (1900, 367).

- ^ a b Freud (1900, 368).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 104–107, 113–116) and de Grazia (2007, 168–170).

- ^ Freud (1900, 575).

- ^ Howard (2003, 411–415).

- ^ Bloom (2003, 58–59); Thompson (2001, 4).

- ^ Showalter (1985).

- ^ Bloom (2003, 57).

- ^ MacCary (1998, 111–113).

- ^ Taylor (2002, 18).

- ^ Taylor (2002, 13).

- ^ Dawson (2002, 176).

- ^ Chambers (1930, vol. 1, 334), cited by Dawson (2002, 176).

- ^ Pitcher and Woudhuysen (1969, 204).

- ^ Hibbard (1987, 17).

- ^ Marsden (2002, 21–22).

- ^ Thompson and Taylor (2006a, 98–99).

- ^ Letter to Sir William Young, 10 January 1773, quoted by Uglow (1977, 473).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 231).

- ^ Moody (2002, 41).

- ^ Moody (2002, 44), quoting Sheridan.

- ^ Gay (2002, 159).

- ^ Dawson (2002, 185–7).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 232–3).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 235–7).

- ^ Holland (2002, 203–5).

- ^ Moody (2002, 54).

- ^ Schoch (2002, 58–75).

- ^ Halliday (1964, 204) and O'Connor (2002, 77).

- ^ George Bernard Shaw in The Saturday Review 2 October, 1897, quoted in Shaw (1961, 81).

- ^ Dawson (2002, 184).

- ^ Dawson (2002, 188).

- ^ William Winter, New York Tribune 26 October 1875, quoted by Morrison (2002, 241).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 241).

- ^ Sarah Bernhardt, in a letter to the London Daily Telegraph, quoted by Gay (2002, 164).

- ^ Gillies et al (2002, 259).

- ^ Gillies et. al. (2002, 261).

- ^ Gillies et. al. (2002, 262).

- ^ Dawson (2002, 180).

- ^ For more on this production, see The MAT production of Hamlet. Craig and Stanislavski began planning the production in 1908 but, due to a serious illness of Stanislavski's, it was delayed until December, 1911. See Benedetti (1998, 188–211).

- ^ Benedetti (1999, 189, 195).

- ^ On Craig's relationship to Russian symbolism and its principles of monodrama in particular, see Taxidou (1998, 38–41); on Craig's staging proposals, see Innes (1983, 153); on the centrality of the protagonist and his mirroring of the 'authorial self', see Taxidou (1998, 181, 188) and Innes (1983, 153).

- ^ A brightly-lit, golden pyramid descended from Claudius' throne, representing the feudal hierarchy, giving the illusion of a single, unified mass of bodies. In the dark, shadowy foreground, separated by a gauze, Hamlet lay, as if dreaming. On Claudius' exit-line the figures remained but the gauze was loosened, so that they appeared to melt away as if Hamlet's thoughts had turned elsewhere. For this effect, the scene received an ovation, which was unheard of at the MAT. See Innes (1983, 152).

- ^ See Innes (1983, 140–175; esp. 165–167 on the use of the screens).

- ^ Innes (1983, 172).

- ^ Hortmann (2002, 214).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 247–8).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 249).

- ^ Morrison (2002, 249–50).

- ^ Smallwood (2002, 102).

- ^ Smallwood (2002, 108).

- ^ Hortmann (2002, 223).

- ^ Burian (1993), quoted by Hortmann (2002, 224–5).

- ^ Gillies et. al. (2002, 267).

- ^ Gillies et. al. (2002, 267).

- ^ Gillies et. al. (2002, 268–9).

- ^ Brode (2001, 117).

- ^ Brode (2001, 117)

- ^ Brode (2001, 118).

- ^ Davies (2000, 171).

- ^ Guntner (2000, 120–121).

- ^ Brode (2001, 125–7).

- ^ Both quotations from Cartmell (2000, 212), where the aim of making Shakespeare "even more popular" is attributed to Zeffirelli himself in an interview given to The South Bank Show in December 1997.

- ^ Guntner (2000, 121–122).

- ^ Crowl (2000, 232).

- ^ Keyishian (2000 78, 79)

- ^ Burnett (2000).

- ^ Howard (2000, 300–301).

- ^ Howard (2000, 301–2).

- ^ Teraoka (1985, 13).

- ^ Brode (2001, 150).

- ^ Vogler (1992, 267–275).

Editions of Hamlet

- Bate, Jonathan, and Eric Rasmussen, eds. 2007. Complete Works. By William Shakespeare. The RSC Shakespeare. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0679642951.

- Edwards, Phillip, ed. 1985. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521293669.

- Hibbard, G. R., ed. 1987. Hamlet. Oxford World's Classics ser. Oxford. ISBN 0192834169.

- Irace, Kathleen O. 1998. The First Quarto of Hamlet. New Cambridge Shakespeare ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521653908.

- Jenkins, Harold, ed. 1982. Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare, second ser. London: Methuen. ISBN 1903436672.

- Lott, Bernard, ed. 1970. Hamlet. New Swan Shakespeare Advanced ser. New ed. London: Longman. ISBN 0582527422.

- Spencer, T. J. B., ed. 1980 Hamlet. New Penguin Shakespeare ser. London: Penguin. ISBN 0140707344.

- Thompson, Ann and Neil Taylor, eds. 2006a. Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare, third ser. Volume one. London: Arden. ISBN 1904271332.

- ———. 2006b. Hamlet: The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare, third ser. Volume two. London: Arden. ISBN 1904271804.

- Wells, Stanley, and Gary Taylor, eds. 1988. The Complete Works. By William Shakespeare. The Oxford Shakespeare. Compact ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198711905.

Secondary sources

- Alexander, Peter. 1964. Alexander's Introductions to Shakespeare. London: Collins.

- Banham, Martin, ed. 1998. The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521434378.

- Benedetti, Jean. 1999. Stanislavski: His Life and Art. Revised edition. Original edition published in 1988. London: Methuen. ISBN 0413525201.

- Blits, Jan H. 2001. Introduction. In Deadly Thought: "Hamlet" and the Human Soul. Langham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 0739102141. 3–22.

- Bloom, Harold. 2001. Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. Open Market ed. Harlow, Essex: Longman. ISBN 157322751X.

- ———. 2003. Hamlet: Poem Unlimited. Edinburgh: Cannongate. ISBN 1841954616.

- Brode, Douglas 2001. Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books. ISBN 0425181766.

- Brown, John Russell. 2006. Hamlet: A Guide to the Text and its Theatrical Life. Shakespeare Handbooks ser. Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403920923.

- Burian, Jarka. 1993. "Hamlet in Postwar Czech Theatre". In Foreign Shakespeare: Contemporary Performance. Ed. Dennis Kennedy. New edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521617081.

- Burnett, Mark Thornton. 2000. "'To Hear and See the Matter': Communicating Technology in Michael Almereyda's Hamlet (2000)". Cinema Journal 42.3: 48–69.

- Carincross, Andrew S. 1936. The Problem of Hamlet: A Solution. Reprint ed. Norwood, PA.: Norwood Editions, 1975. ISBN 0883051303.

- Cartmell, Deborah. 2000. "Franco Zeffirelli and Shakespeare". In Jackson (2000, 212–221).

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever. 1923. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 volumes, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198115113.

- ———. 1930. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988. ISBN 0198117744.

- Crowl, Samuel. 2000. "Framboyant Realist: Kenneth Branagh". In Jackson (2000, 222–240).

- Crystal, David, and Ben Crystal. 2005. The Shakespeare Miscellany. New York: Penguin. ISBN 0140515550.

- Davies, Anthony. 2000. "The Shakespeare films of Laurence Olivier". In Jackson (2000, 163–182).

- Dawson, Anthony B. 1995. Hamlet. Shakespeare in Performance ser. New ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN 0719046254.

- ———. 2002. "International Shakespeare". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 174–193).

- Duthie, George Ian. 1941. The "Bad" Quarto of "Hamlet": A Critical Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eliot, T.S. 1920. "Hamlet and his Problems". In The Sacred Wood: Essays in Poetry and Criticism. London: Faber & Gwyer. ISBN 0416374107.

- Foakes, R. A. 1993. Hamlet versus Lear: Cultural Politics and Shakespeare's Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521607051.

- French, George Russell. 1869. Shakspeareana Geologica. London: Macmillan. Reprinted New York: AMS, 1975. ISBN 0404025757.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1900. The Interpretation of Dreams. Trans. James Strachey. Ed. Angela Richards. The Penguin Freud Library, vol. 4. London: Penguin, 1991. ISBN 0140147947.

- Gay, Penny. 2002. "Women and Shakespearean Performance". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 155–173).

- Gillies, John, Ryuta Minami, Ruru Li, and Poonam Trivedi. 2002. "Shakespeare on the Stages of Asia". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 259–283).

- Greg, Walter Wilson. 1955. The Shakespeare First Folio, its Bibliographical and Textual History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 115185549X.

- Guntner, J. Lawrence. 2000. "Hamlet, Macbeth and King Lear on film". In Jackson (2000, 117–134).

- Halliday, F. E. 1964. A Shakespeare Companion 1564–1964. Shakespeare Library ser. Baltimore, Penguin, 1969. ISBN 0140530118.

- Hattaway, Michael. 1982. Elizabethan Popular Theatre: Plays in Performance. Theatre Production ser. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710090528.

- Holland, Peter. 2002. "Touring Shakespeare". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 194–211).

- Hortmann, Wilhelm. 2002. "Shakespeare on the Political Stage in the Twentieth Century". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 212–229).

- Howard, Jean E. 2003. "Feminist Criticism". In Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Ed. Stanley Wells and Lena Orlin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199245223. 411–423.

- Howard, Tony. 2000. "Shakespeare's Cinematic Offshoots". In Jackson (2000, 303–323).

- Hurstfield, Joel and James Sutherland. 1964. Shakespeare's World. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Innes, Christopher. 1983. Edward Gordon Craig. Directors in Perspective ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521273838.

- Jackson, MacDonald P. 1991. "Editions and Textual Studies Reviewed". In Shakespeare Survey 43, The Tempest and After. Ed. Stanley Wells. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521395291. 255–270.

- Jackson, Russell, ed. 2000. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge Companions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521639751.

- Jenkins, Harold. 1955. "The Relation Between the Second Quarto and the Folio Text of Hamlet". Studies in Bibliography 7: 69–83.

- Keyishian, Harry. 2000. "Shakespeare and Movie Genre: The Case of Hamlet". In Jackson (2000, 72–84).

- Kirsch, A. C. 1968. "A Caroline Commentary on the Drama". Modern Philology 66: 256-61.

- Knowles, Ronald. 1999. "Hamlet and Counter-Humanism." Renaissance Quarterly 52.4: 1046–69.

- Lacan, Jacques. 1959. "Desire and the Interpretation of Desire in Hamlet". In Literature and Psychoanalysis: The Question of Reading Otherwise. Ed. Shoshana Felman. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982. Originally appeared as a double issue of Yale French Studies, nos. 55/56 (1977). ISBN 080182754X.

- Lennard, John. 2007. William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Literature Insights ser. Humanities-Ebooks, 2007. ISBN 184760028X.

- MacCary, W Thomas. 1998. "Hamlet": A Guide to the Play. Greenwood Guides to Shakespeare ser. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313300828.

- Marcus, Leah S. 1988. Puzzling Shakespeare: Local Readings and Its Discontents. The New Historicism: Studies in Cultural Poetics ser. Reprinted ed. Berkley: University of California Press, 1992. ISBN 0520071913.

- Marsden, Jean I. 2002. "Improving Shakespeare: from the Restoration to Garrick". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 21–36).

- Matheson, Mark. 1995. "Hamlet and 'A Matter Tender and Dangerous'". Shakespeare Quarterly 46.4: 383-97.

- Matus, Irvin Leigh. 1994. Shakespeare, in Fact. New ed. New York: Continuum International Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0826409288.

- Moody, Jane. 2002. "Romantic Shakespeare". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 37–57).

- Morrison, Michael A. 2002. "Shakespeare in North America". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 230–258).

- O'Connor, Marion. 2002. "Reconstructive Shakespeare: Reproducing Elizabethan and Jacobean Stages". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 76–97).

- Ogburn, Charlton. 1988. The Mystery of William Shakespeare. London : Cardinal. ISBN 0747402558.

- Patterson, Annabel. 1984. Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England. Reprint ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991. ISBN 0299099547.

- Pennington, Michael. 1996. "Hamlet": A User's Guide. London: Nick Hern. ISBN 185459284X.

- Pitcher, John and Henry Woudhuysen. 1969. Shakespeare Companion, 1564–1964. London: Penguin. ISBN 0140530118.

- Rosenberg, Marvin. 1992. The Masks of Hamlet. London: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0874134803.

- Rowse, Alfred Leslie. 1963. William Shakespeare: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. Reprinted New York : Barnes & Noble Books, 1995. ISBN 1566198046.

- Saxo, and William Hansen. 1983. Saxo Grammaticus & the Life of Hamlet. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803223188.

- Schoch, Richard W. 2002. "Pictorial Shakespeare". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 58–75).

- Shapiro, James. 2005. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. London: Faber, 2006. ISBN 0571214819.

- Shaw, George Bernard. 1961. Shaw on Shakespeare. Ed. Edwin Wilson. New York: Applause. ISBN 1557835616.

- Showalter, Elaine. 1985. "Representing Ophelia: Women, Madness, and the Responsibilities of Feminist Criticism." In Shakespeare and the Question of Theory. Ed. Patricia Parker and Geoffrey Hartman. New York and London: Methuen. ISBN 0416369308. 77–94.

- Smallwood, Robert. 2002. "Twentieth-century Performance: The Stratford and London Companies". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 98–117).

- Taxidou, Olga. 1998. The Mask: A Periodical Performance by Edward Gordon Craig. Contemporary Theatre Studies ser. volume 30. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 9057550466.

- Taylor, Gary. 2002. "Shakespeare Plays on Renaissance Stages". In Wells and Stanton (2002, 1–20).

- Teraoka, Arlene Akiko. 1985. The Silence of Entropy or Universal Discourse : the Postmodernist Poetics of Heiner Müller. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0820401900.

- Thompson, Ann. 2001. "Shakespeare and sexuality" in Catherine M S Alexander and Stanley Wells Shakespeare and Sexuality. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521804752. 1–13.

- Thomson, Peter. 1983. Shakespeare's Theatre. Theatre Production ser. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0710094809.

- Tomm, Nigel. 2006. Shakespeare's "Hamlet" Remixed. BookSurge. ISBN 1419648926.

- Uglow, Jenny. 1977. Hogarth: A Life and a World. New ed. London: Faber and Faber, 2002. ISBN 0571193765.

- Vickers, Brian, ed. 1974a. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage. Volume one (1623–1692). New ed. London: Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0415134048.

- ———. 1974b. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage. Volume four (1753–1765). New ed. London: Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0415134072.

- ———. 1974c. Shakespeare: The Critical Heritage. Volume five (1765–1774). New ed. London: Routledge, 1995. ISBN 0415134080.

- Vogler, Christopher. 1992. The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters. Second revised ed. London: Pan Books, 1999. ISBN 0330375911.

- Ward, David. 1992. "The King and 'Hamlet'". Shakespeare Quarterly 43.3: 280–302.

- Weimann, Robert. 1985. "Mimesis in Hamlet". In Shakespeare and the Question of Theory. Ed. Patricia Parker and Geoffrey Hartman. New York and London: Methuen. ISBN 0416369308. 275–291.

- Wells, Stanley, and Sarah Stanton, eds. 2002. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Stage. Cambridge Companions to Literature ser. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052179711X.

- Wilson, John Dover. 1932. The Essential Shakespeare: A Biographical Adventure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ———. 1934. The Manuscript of Shakespeare's "Hamlet" and the Problems of its Transmission: An Essay in Critical Bibliography. 2 volumes. Cambridge: The University Press.

- ———. 1935. What Happens in Hamlet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959. ISBN 0521068355.

- Winstanley, Lilian. 1921. Hamlet and the Scottish succession, Being an Examination of the Relations of the Play of Hamlet to the Scottish Succession and the Essex Conspiracy. London: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted Philadelphia : R. West, 1977. ISBN 084922912X.

- Wofford, Susanne L. 1994. "A Critical History of Hamlet." In Hamlet: Complete, Authoritative Text with Biographical and Historical Contexts, Critical History, and Essays from Five Contemporary Critical Perspectives. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martins Press. ISBN 0312089864.

External links

- Hamlet on the Ramparts — from MIT's Shakespeare Electronic Archive

- Hamletworks.org A highly-respected scholarly resource with multiple versions of Hamlet, numerous commentaries, concordances, facsimiles, and more.

- ISE — Internet Shakespeare Editions provides authentic transcripts and facsimilies of the First Quarto, Second Quarto, and First Folio versions of the play.

- Hamlet — plain vanilla text at Project Gutenberg.

- "Nine Hamlets" — An analysis of the play and 9 film versions, at the Bright Lights Film Journal

- "The Hamlet Weblog" — a weblog about the play.

- "HyperHamlet" — A project at the University of Basel