Humanism: Difference between revisions

Richard001 (talk | contribs) →Speciesism: Weasel words |

Richard001 (talk | contribs) Better still, a citation (Peter Singer on speciesism) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

=== Speciesism === |

=== Speciesism === |

||

Some |

Some have interpreted humanism to be a form of [[speciesism]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/200410--.htm |title=Taking Humanism Beyond Speciesism, by Peter Singer |author=[[Peter Singer]] |accessdate=2007-01-11}}</ref>, mostly because of the word itself. The term points out the focus on human affairs and concerns ''as opposed to those of gods'' and is not intended to be taken as opposed to other species, and does not imply that non-human species deserve no respect; individual humanists or humanist groups may hold any position regarding issues of [[animal rights]]. |

||

=== Optimism === |

=== Optimism === |

||

Revision as of 08:39, 11 January 2007

- See also the specific life stance known as Humanism

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

Humanism is a broad category of active ethical philosophies that affirm the dignity and worth of all people, based on the ability to determine right and wrong by appeal to universal human qualities—particularly rationalism. Humanism is a component of a variety of more specific philosophical systems, and is also incorporated into some religious schools of thought. Humanism entails a commitment to the search for truth and morality through human means in support of human interests. In focusing on the capacity for self-determination, humanism rejects transcendental justifications, such as a dependence on faith, the supernatural, or divinely revealed texts. Humanists endorse universal morality based on the commonality of human nature, suggesting that solutions to human social and cultural problems cannot be parochial.

Aspects

Religion

Humanism can be used in some ways to fulfill or supplement the role of religions and therefore qualifies as a stance on religion. It is entirely compatible with naturalism[citation needed] (and therefore atheism), but doesn't strictly require either of these, and is compatible with some religions.

While the broad category of humanism encompasses intellectual currents running through a wide variety of philosophical or religious thought, it is embraced by some people as a complete life stance. For more on this, see Humanism (life stance).

What humanism clearly rejects is deference to supernatural beliefs in resolving human affairs, not necessarily the beliefs themselves.

For that matter, agnosticism or atheism on its own doesn't necessarily entail humanism. Indeed, many different and incompatible philosophies are atheistic in nature.

Renaissance humanism, and its emphasis on returning to the sources, contributed to the Protestant reformation in helping to gain what they believe was a more accurate translation of Biblical texts.

Knowledge

According to humanism, it is up to humans to find the truth, not wait for it to be handed to them through revelation, mysticism, tradition, or anything else that is incompatible with the application of logic to the evidence. In demanding that humans avoid blindly accepting unsupported beliefs, it supports scientific skepticism and the scientific method, rejecting authoritarianism and extreme skepticism, and rendering faith an unacceptable basis for action. Likewise, humanism asserts that knowledge of right and wrong is based on one's best understanding of one's individual and joint interests, rather than stemming from a transcendental or arbitrarily local source.

Speciesism

Some have interpreted humanism to be a form of speciesism[1], mostly because of the word itself. The term points out the focus on human affairs and concerns as opposed to those of gods and is not intended to be taken as opposed to other species, and does not imply that non-human species deserve no respect; individual humanists or humanist groups may hold any position regarding issues of animal rights.

Optimism

Humanism features an optimistic attitude about the capacity of people, but it does not involve believing that human nature is purely good or that each and every person is capable of living up to the humanist ideals of rationality and morality. If anything, there is the recognition that living up to one's potential is hard work and requires the help of others. The ultimate goal is human flourishing; making life better for all humans. Even among humanists who do believe in some sort of an afterlife, the focus is on doing good and living well in the here and now, and leaving the world better for those who come after, not on suffering through life to be rewarded afterward.

History

Contemporary humanism can be traced back through the Renaissance to its ancient Greek roots.

The evolution of the meaning of the word humanism is fully explored in Nicolas Walter Humanism — What's in the Word. [2]

Greek roots

Sixth century B.C.E pantheists Thales of Miletus and Xenophanes of Colophon prepared the way for later Greek humanist thought. Thales is credited with creating the maxim "Know thyself", and Xenophanes refused to recognize the gods of his time and reserved the divine for the principle of unity in the universe. Later Anaxagoras, often described as the "first freethinker", contributed to the development of science as a method of understanding the universe. Pericles, a pupil of Anaxagoras, influenced the development of democracy, freedom of thought, and the exposure of superstitions. Although little of their work survives, Protagoras and Democritus both espoused agnosticism and a spiritual morality not based on the supernatural. The historian Thucydides is noted for his scientific and rational approach to history.

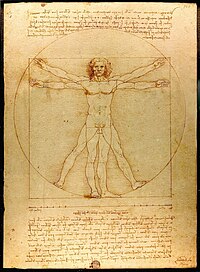

Renaissance

Renaissance humanism was a broad movement that affected the social, cultural, literary and political landscape of Europe. Beginning in Florence in the last decades of the 14th century, Renaissance humanism revived the study of Latin and Greek, with the resultant revival of the study of science, philosophy, art and poetry of classical antiquity. The revival was based on interpretations of Roman and Greek texts, whose emphasis upon art and the senses marked a great change from the contemplation on the Biblical values of humility, introspection, and meekness. Beauty was held to represent a deep inner virtue and value, and an essential element in the path towards God.

The crisis of Renaissance humanism came with the trial of Galileo, which forced the choice between basing the authority of one's beliefs on one's observations, or upon religious teaching. The trial made the contradictions between humanism and traditional religion visibly apparent to all, and humanism was branded a "dangerous doctrine."

Renaissance humanists believed that the liberal arts (music, art, grammar, rhetoric, oratory, history, poetry, using classical texts, and the studies of all of the above) should be practiced by all levels of wealth. They also approved of self, human worth and individual dignity.

Noteworthy humanists scholars from this period include the Dutch theologist Erasmus, the English author Thomas More, the French writer Francois Rabelais, and the Italian scholar Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

Modern era

One of the earliest forerunners of contemporary chartered humanist organizations was the Humanistic Religious Association formed in 1853 in London. This early group was democratically organized, with male and female members participating in the election of the leadership and promoted knowledge of the sciences, philosophy, and the arts.

In 1929 Charles Francis Potter founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included Julian Huxley, John Dewey, Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. Potter was a minister from the Unitarian tradition and in 1930 he and his wife, Clara Cook Potter, published Humanism: A New Religion. Throughout the 1930s Potter was a well-known advocate of women’s rights, access to birth control, "civil divorce laws", and an end to capital punishment. F.C.S. Schiller considered his work to be tied to the humanist movement. Schiller himself was influenced by the pragmatism of William James.

Raymond B. Bragg, the associate editor of The New Humanist, sought to consolidate the input of L. M. Birkhead, Charles Francis Potter, and several members of the Western Unitarian Conference. Bragg asked Roy Wood Sellars to draft a document based on this information which resulted in the publication of the Humanist Manifesto in 1933. The Manifesto and Potter's book became the cornerstones of modern humanism. Both of these sources envision humanism as a religion.

In 1941 the American Humanist Association was organized. Noted members of The AHA include Isaac Asimov, who was the president before his death, and writer Kurt Vonnegut, who is the current honorary president.

Modern humanist philosophies

There are many people who consider themselves humanists, and much variety in the exact type of humanism to which they subscribe. There is some disagreement over terminology and definitions, with some people using narrower or broader interpretations. Not all people who call themselves humanists hold beliefs that are genuinely humanistic, and not all people who do hold humanistic beliefs apply the label of humanism to themselves.

All of this aside, humanism can be divided into secular and religious types.

Secular humanism

Secular humanism is the branch of humanism that rejects theistic religious belief and the existence of a supernatural. It is often associated with scientists and academics, although it is not at all limited to these groups. Secular humanists generally believe that following humanist principles naturally leads to secularism, on the basis that religious views cannot be supported rationally. There are secular humanistic organizations, though these could not be accurately described as churches.

More often than not, secular humanism is what people are referring to when they speak of humanism in general, making it something of a default. Some secular humanists take this even further by denying that religious humanists qualify as genuine humanists. Others feel that the ethical side of humanism transcends the issue of religion, because being a good person is more important than supernatural beliefs.

Some people use the term humanist to refer to all atheists, though the accuracy of this usage is disputed.

Some secular humanists prefer the term Humanist (capital 'H', and no adjective), as unanimously endorsed by General Assembly of the International Humanist and Ethical Union following universal endorsement of the Amsterdam Declaration 2002.

Religious humanism

Religious humanism is the branch of humanism that considers itself religious (based on a functional definition of religion), or embraces some form of theism, deism, or supernaturalism, without necessarily being allied with organized religion, as such. If they do, religious humanists often associate themselves with Unitarian Universalism. It is often associated with artists, liberal Christians, and scholars in the liberal arts. Other types of people that may be considered religious humanists are those who, despite believing in a religion, don't consider it necessary to derive all their moral values from it. Some feel that, because their religious beliefs are moral, and therefore humane, they are humanists. In particular, it is not uncommon for religious humanitarians to be referred to as humanists, although the accuracy of this usage is disputed.

A number of religious humanists feel that secular humanism is too coldly logical and rejects the full emotional experience that makes humans human. From this comes the notion that secular humanism is inadequate in meeting the human need for a socially fulfilling philosophy of life. Disagreements over things of this nature have resulted in friction between secular and religious humanists, despite their similarities.

Other forms of humanism

Humanism is also sometimes used to describe "humanities" scholars, (particularly scholars of the Greco-Roman classics). As mentioned above, it is sometimes used to mean humanitarianism. There is also a school of humanistic psychology, and an educational method.

Educational humanism

Humanism, as a current in education, began to dominate school systems in the 17th century. It held that the studies that develop human intellect are those that make humans "most truly human". The practical basis for this was faculty psychology, or the belief in distinct intellectual faculties, such as the analytical, the mathematical, the linguistic, etc. Strengthening one faculty was believed to benefit other faculties as well (transfer of training). A key player in the late 19th-century educational humanism was U.S. Commissioner of Education W.T. Harris, whose "Five Windows of the Soul" (mathematics, geography, history, grammar, and literature/art) were believed especially appropriate for "development of the faculties". Educational humanists believe that "the best studies, for the best kids" are "the best studies" for all kids. While humanism as an educational current was largely discredited by the innovations of the early 20th century, it still holds out, in some elite preparatory schools and some high school disciplines (especially, in literature).

See also

Manifestos and statements setting out humanist viewpoints

Forms of humanism

- Marxist humanism

- New Humanism

- Posthumanism

- Religious humanism

- Renaissance humanism

- Secular humanism

- Transhumanism

- Incarnational humanism

Related philosophies

Organizations

- Institute for Humanist Studies

- International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU)

- Rationalist International

- Freethought Association

- Council for Secular Humanism

- International Humanist and Ethical Union

- Rationalist International

- Institute for Humanist Studies

- American Humanist Association

- British Humanist Association

- Human-Etisk Forbund, the Norwegian Humanist Association

- Humanist Society of Scotland

- Humanist Association of Ireland

- Sidmennt, the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association

- Society for Humanistic Judaism

- Humanist International

- Humanist Movement

- Humanist Party

For more organizations see Category:Humanist associations

Other

- Antihumanism

- Humanistic psychology

- Social psychology

- Religious freedom — freedom of religion and belief

- Speciesism

References

Notes

- ^ Peter Singer. "Taking Humanism Beyond Speciesism, by Peter Singer". Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ^ Walter, Nicolas, 1997 Humanism — What's in the Word, Rationalist Press Association, London, ISBN 0-301-97001-7.

Bibliography

- Petrosyan, M. 1972 Humanism: Its Philosophical, Ethical, and Sociological Aspects, Progress Publishers, Moscow.

External links

Manifestos and statements setting out humanist viewpoints

- Humanist Manifesto I (1933)

- Humanist Manifesto II (1973)

- A Secular Humanist Declaration (1980)

- Amsterdam Declaration (2002)

- Humanist Manifesto III (2003)

Introductions to humanism

- What Is Humanism? from the American Humanist Association

- Humanism: Why, What, and What For, In 882 Words

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Civic Humanism

- Catholic Encyclopedia article on Renaissance Humanism

Organizations

- International

- Europe

- British Humanist Association

- Humanist Society of Scotland

- UK Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association

- Humanist Movement — Europe

- Humanist Movement — German

- Humanist Association of N. Ireland

- Humanist Association of Ireland

- Humanist Movement — Italy

- Humanist n.e.t. — German/ English

- Norwegian Humanist Association

- Swedish Humanist Association

- Romanian association Solidarity for Freedom of Conscience — Romanian/ English

- Virtual Sociedade Humanista Mineira

- North America

- American Humanist Association

- The Church of Spiritual Humanism

- HUUmanists, Unitarian Universalist publishers of the journal Religious Humanism

- Humanist Association of Canada

- Chicago humanist wiki pages

- Institute for Humanist Studies

- Humanist Association of Manitoba

- Society of Ontario Freethinkers

- The Humanist Fellowship of San Diego

- Council for Secular Humanism

- Freethought Association of West Michigan

Web articles

- New Humanist British magazine from the Rationalist Press Association (RPA)

- Nanovirus — A humanist perspective on politics, technology and culture

- Modern Humanist An Online Journal for Modern Humanism, Humanist Philosophy & Life