Jeremiah

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (January 2012) |

Jeremiah | |

|---|---|

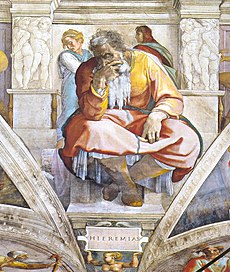

Jeremiah, as depicted by Michelangelo from the Sistine Chapel ceiling | |

| Born | c. 655 BC |

| Died | 586 BC |

| Occupation | Prophet |

| Parent | Hilkiah |

Jeremiah (/[invalid input: 'icon']dʒɛr[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈmaɪ.ə/;[1] Hebrew:יִרְמְיָה, Modern Hebrew:Yirməyāhū, IPA: jirməˈjaːhu, Tiberian:Yirmĭyahu, Greek:Ἰερεμίας), meaning "Yah exalts", also called the "Weeping prophet" [2] was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. Jeremiah is traditionally credited with authoring the Book of Jeremiah, 1 Kings, 2 Kings and the Book of Lamentations, [3] with the assistance and under the editorship of Baruch ben Neriah, his scribe and disciple. Judaism considers the Book of Jeremiah part of its canon, and regards Jeremiah as the second of the major prophets. Islam considers Jeremiah a prophet, and is listed as a prophet in all the collections of Stories of the Prophets.[citation needed] Christianity also regards Jeremiah as a prophet and he is quoted in the New Testament.[4] It has been interpreted that Jeremiah “spiritualized and individualized religion and insisted upon the primacy of the individual’s relationship with God.”[5]

About a year after King Josiah of Judah had turned the nation toward repentance from the widespread idolatrous practices of his father and grandfather. Jeremiah’s job was to reveal the sins of the people and explain the reason for the impending disaster (destruction by the Babylonian army and captivity),[6][7] “And when your people say, 'Why has the LORD our God done all these things to us?' you shall say to them, 'As you have forsaken me and served foreign gods in your land, so you shall serve foreigners in a land that is not yours.'"[8] God’s personal message to Jeremiah, “Attack you they will, overcome you they can’t,”[9] was fulfilled many times in the Biblical narrative, Jeremiah was attacked by his own brothers,[10] beaten and put into the stocks by a priest and false prophet,[11] imprisoned by the king,[12] threatened with death,[13] thrown into a cistern by Judah’s officials,[14] and opposed by a false prophet.[15] When Nebuchadnezzar seized Jerusalem in 586 BC,[16] he ordered that Jeremiah be freed from prison and treated well.[17]

Lineage and early life

According to the Book of Jeremiah, Jeremiah was a kohen (Jewish priest),[18] from a landowning family.[19] It is mentioned that he had a joyful early life,[20] however, the difficulties in Jeremiah and the Book of Lamentations have prompted scholars to refer to him as "the weeping prophet".[21] Jeremiah was called to prophetic ministry in c. 626 BC,[22] He was the son of Hilkiah from the village of Anathoth [23][24] The Book of Jeremiah says that Jeremiah was called by Elohim to prophesy Jerusalem’s destruction [25] that would occur by invaders from the North.[26] This was because Israel had been unfaithful to the laws of the covenant and had forsaken God by worshiping the Baals.[27] The people of Israel had even gone as far as building high altars to Baal in order to burn their children in fire as offerings to Baal.[28] This nation had deviated so far from God that they had actually broken the covenant, causing God to withdraw His blessings. Jeremiah was guided by God to proclaim that the nation of Israel would be faced with famine, be plundered and taken captive by foreigners who would exile them to a foreign land.[29][30]

Chronology

Jeremiah’s ministry was active from the thirteenth year of Josiah, king of Judah (3298 HC,[31] or 626 BC[32]), until after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of Solomon’s Temple in (3358 HC, or 587 BC[33]). This period spanned the reigns of five kings of Judah: Josiah, Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim, Jehoichin, and Zedekiah.[34] The Hebrew-language chronology work Seder HaDoroth gives Jeremiah's final year of prophecy to be (3350 HC), whereby he transmitted his teachings to Baruch ben Neriah.[35]

Biblical narrative

Calling

The Lord called Jeremiah to prophetic ministry in about 626 BC,[22] about one year after Josiah king of Judah had turned the nation toward repentance from the widespread idolatrous practices of his father and grandfather. Ultimately, Josiah’s reforms would not be enough to preserve Judah and Jerusalem from destruction, both because the sins of Manasseh, Josiah’s grandfather, had gone too far [36] and as a result of Judah's return to Idolatry (Jer 11.10ff.). Such was the lust of the nation for false gods that after Josiah’s death, the nation would quickly return to the gods of the surrounding nations.[37] Jeremiah was appointed to reveal the sins of the people and the coming consequences.[6][7]

In contrast to Isaiah, who eagerly accepted his prophetic call,[38] and similar to Moses who was less than eager,[39] Jeremiah resisted the call by complaining that he was only a child and did not know how to speak.[24] However, the Lord insisted that Jeremiah go and speak as commanded, and he touched Jeremiah’s mouth and put the word of the Lord into Jeremiah’s mouth.[40] God told Jeremiah to “Get yourself ready!”[41] The character traits and practices Jeremiah was to acquire in order to be ready are specified in Jeremiah 1 and include not being afraid, standing up to speak, speaking as told, and going where sent.[42] Other disciplines that contributed to the training of the young prophet and confirmation of his message are described as not turning to the people,[43] not marrying or fathering children,[44] not going to weddings or funerals,[45] not sitting in a house with feasting,[46] and not sitting in the company of merrymakers.[47] Since Jeremiah emerges well trained and fully literate from his earliest preaching, the relationship between him and the Shaphan family has been used to suggest that he may have trained at the scribal school in Jerusalem over which Shaphan presided.[48][49]

In his early ministry, Jeremiah was primarily a preaching prophet,[50] going where the Lord directed him to preach oracles throughout Israel.[49] He condemned idolatry,[51] the greed of priests, and false prophets.[52] Many years later, God instructed Jeremiah to write down these early oracles and other messages.[53]

Persecution

Jeremiah's ministry prompted naysayers to plot against him. Even the people of Anathoth sought to kill him. (Jer.11) Unhappy with Jeremiah’s message, possibly for concern that it would shut down the Anathoth sanctuary, his priestly kin and the men of Anathoth conspired to take his life. However, the Lord revealed the conspiracy to Jeremiah, protected his life, and declared disaster for the men of Anathoth.[49][54] When Jeremiah complains to the Lord about this persecution, the Lord explains that the attacks on him will become worse.[55]

Physical persecution started when the priest Pashur ben Immer, a temple official, sought out Jeremiah to have him beaten and put him in the stocks at the Upper Gate of Benjamin for a day. After this, Jeremiah expresses lament over the difficulty that speaking God’s word has caused him and regrets becoming a laughingstock and the target of mockery.[56] He recounts how if he tries to shut the word of the Lord inside and not mention God’s name, the word becomes like fire in his heart and he is unable to hold it in.[57] The experiences are so troubling for Jeremiah, that he expresses regret at ever being born.

Conflicts with false prophets

At the same time while Jeremiah was prophesying coming destruction because of the sins of the nation, a number of other prophets were prophesying peace.[58] The Lord had Jeremiah speak against these false prophets.

For example, during the reign of King Zedekiah, The Lord instructed Jeremiah to make a yoke of the message that the nation would be subject to the king of Babylon and that listening to the false prophets would bring a much worse disaster. The prophet Hananiah opposed Jeremiah’s message. He took the yoke off of Jeremiah’s neck, broke it, and prophesied to the priests and all the people that within two years the Lord would break the yoke of the king of Babylon, but the lord spoke to Jeremiah saying "Go and speak to Hananiah saying, you have broken the yoke of wood, but you have made instead a yoke of iron." (see: Jeremiah 28:13)

Babylon

The Biblical narrative portrays Jeremiah as being subject to additional persecutions. After Jeremiah prophesied that Jerusalem would be handed over to the Babylonian army, the king’s officials, including Pashur the priest, tried to convince King Zedekiah that Jeremiah should be put to death because he was discouraging the soldiers as well as the people. Zedekiah answered that he would not oppose them. Consequently, the king’s officials took Jeremiah and put him down into a cistern, where he sank down into the mud. The intent seemed to be to kill Jeremiah by allowing him to starve to death in a manner designed to allow the officials to claim to be innocent of his blood.[59] A Cushite rescued Jeremiah by pulling him out of the cistern, but Jeremiah remained imprisoned until Jerusalem fell to the Babylonian army in 587 BC.[60]

The Babylonians released Jeremiah, and showed him great kindness, allowing Jeremiah to choose the place of his residence, according to a Babylonian edict. Jeremiah accordingly went to Mizpah in Benjamin with Gedaliah, who had been made governor of Judea.[61]

Egypt

Johanan succeeded Gedaliah, who had been assassinated by an Israelite prince in the pay of Ammon "for working with the Babylonians." Refusing to listen to Jeremiah's counsel, Johanan fled to Egypt, taking with him Jeremiah and Baruch, Jeremiah's faithful scribe and servant, and the king's daughters.[62] There, the prophet probably spent the remainder of his life, still seeking in vain to turn the people to God from whom they had so long revolted.[63] There is no authentic record of his death.

Prophetic parables

The biblical narrative includes a number of cases of Jeremiah being given unusual instructions requiring him to act out parables or behave in ways contrary to expectations of prophetic office. Much like the prophet Isaiah who had to walk stripped and barefoot for three years[64] and the prophet Ezekiel who had to lie on his side for 390 days and eat measured food,[65] Jeremiah is instructed to perform a number of prophetic parables[66] to illustrate the Lord’s message to his people. For example, Jeremiah buys a clay jar and smashes it in the Valley of Ben Hinnom in front of elders and priests to illustrate that the Lord will smash the nation of Judah and the city of Judah beyond repair.[67] The Lord instructs Jeremiah to make a yoke from wood and leather straps and to put it on his own neck to demonstrate how the Lord will put the nation under the yoke of the king of Babylon.[68]

The linen belt

In this parable, the Lord asked Jeremiah to buy a belt and wear it around his waist for a time ensuring that it did not come in contact with water. Later, the Lord came to Jeremiah again and then asked him to take the belt to Perath and to hide it in a rock crevice. Several days later he was asked to return to where he hid the belt and retrieve it. When Jeremiah did so, the belt was completely ruined and useless. Just as a belt is bound around the waist, God had bound the people of Israel to his covenant. The ruining of the belt was to be like the ruining of Judah and Jerusalem’s pride. Its uselessness is as useless as the gods they served and worshiped.[69]

Wineskins

In Jeremiah's ministry, he declared that God had likened the filling of wineskins to filling with drunkenness all who lived in the land of Israel, including the kings who sat on David’s throne, the priests, the prophets and all those in Jerusalem. Then it was proclaimed that God would smash them one against the other, both parents and children, and they were not to be interceded for with pity, mercy nor compassion.[70] God was so angry over their sins, that he says that even if Moses and Samuel were to intercede for the people, he would not relent.[71]

The potter

While at the potter's house, Jeremiah watched a craftsman shaping a bowl from clay on the wheel. When it became marred in his hands, the potter then reshaped it into another bowl that suited best. This is how God wanted Jeremiah to envision the reshaping of Israel.(Jeremiah 18:1–6)

The Rechabites

In order to contrast the people’s disobedience with the obedience of the Rechabites, the Lord has Jeremiah invite the Rechabites to drink wine, in disobedience to their ancestor’s command. The Rechabites refused, and God commended them.

"This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: Go and tell the men of Judah and the people of Jerusalem, “Will you not learn a lesson and obey my words?” declares the Lord. “Jonadab son of Recab ordered his sons not to drink wine and this command has been kept. To this day they do not drink wine, because they obey their forefather's command. But I have spoken to you again and again, yet you have not obeyed me. Again and again I sent all my servants the prophets to you. They said, ‘Each of you must turn from your wicked ways and reform your actions; do not follow other gods to serve them. Then you will live in the land I have given to you and your fathers.’ But you have not paid attention or listened to me. The descendants of Jonadab son of Recab have carried out the command their forefather gave them, but these people have not obeyed me.” Jeremiah 35:13–16 (NIV)

The field

During the siege of Jerusalem, when it was finally obvious that Jeremiah’s prophecies of disaster would be fulfilled and that destruction and exile were imminent, the Lord instructed Jeremiah to make a real-estate investment by purchasing a field at Anathoth from his cousin Hanamel. Jeremiah obeyed, weighed out the silver on scales, and had the deed witnessed and sealed. The Lord was making the point that the nation would eventually be restored and that houses and fields would once again be bought in the land.[72]

World views

Jewish views

Commentator Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote that the book is written as if Jeremiah not only heard as words but personally felt in his body and emotions the experience of what he prophesied:

- "Are not all my words as fire, sayeth the LORD, and a hammer that shatters rock"

was a clue as to how difficult the overwhelming, personality-shattering experience of being a vehicle for Divine revelation was, on one of the most difficult tasks ever assigned, and how difficult it was to be able to see, in advance, one's own failure.

Rabbinic literature

In Jewish rabbinic literature, especially the aggadah, Jeremiah and Moses are often mentioned together;[73] their life and works being presented in parallel lines. The following ancient midrash is especially interesting, in connection with Deut. xviii. 18, in which "a prophet like Moses" is promised: "As Moses was a prophet for forty years, so was Jeremiah; as Moses prophesied concerning Judah and Benjamin, so did Jeremiah; as Moses' own tribe [the Levites under Korah] rose up against him, so did Jeremiah's tribe revolt against him; Moses was cast into the water, Jeremiah into a pit; as Moses was saved by a slave (the slave of Pharaoh's daughter); so, Jeremiah was rescued by a slave (Ebed-melech); Moses reprimanded the people in discourses; so did Jeremiah."[74]

Islamic views

As with many other prophets of the Hebrew Bible, Jeremiah is also regarded as a prophet in Islam by many Muslims. Jeremiah is not mentioned in the Qur'an, but Muslim exegesis and literature narrates many instances from the life of Jeremiah and tradition fleshes out his narrative. Muslim literature narrates a detailed account of the destruction of Jerusalem, which parallels the account given in the Book of Jeremiah.[75]

Christian views

God is the one who gives a heart to His people to know Him in Jeremiah 24:7. This theme is carried through a promise of a New Covenant which rests on God. In Augustine's view even the perseverance rests on God. Augustine says, drawing from Jeremiah 32:40, "Because perseverance is much more difficult when the persecutor is engaged in preventing a man's perseverance; and therefore he is sustained in his perseverance unto death. Hence it is more difficult to have the former perseverance,-easier to have the latter; but to Him to whom nothing is difficult it is easy to give both. For God has promised this, saying, 'I will put my fear in their hearts, that they may not depart from me.' And what else is this than, “Such and so great shall be my fear that I will put into their hearts that they will perseveringly cleave to me”?" in his work , On the Gift of Perseverance 2. [76]

Scholarly views

Scholars cannot with any certainty prove the authorship of Jeremiah, although consensus has gathered around a thesis of multiple sources, mainly because of the contrast between the poetic discourses and the prose narrative. It is possible that the Deuteronomist and/or the scribe Baruch recorded and edited the original prophecies.[77] Some modern Scholars think the Deuteronomic School edited Jeremiah because of the similarity of phrasing between the books of Jeremiah and Deuteronomy. For example, Egypt is referred to as an "iron furnace" in both Jeremiah 11:4 and Deuteronomy 4:20.[78] They also share a similar view of divine justice.[78]

Nebo-Sarsekim tablet

In July 2007, Assyrologist Michael Jursa translated a cuneiform tablet dated to 595 BC, as describing a Nabusharrussu-ukin as "the chief eunuch" of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. Jursa hypothesized that this reference might be to the same individual as the Nebo-Sarsekim mentioned in Jeremiah 39:3.[79][80]

Cultural influence

Jeremiah inspired the French noun jérémiade, and subsequently the English jeremiad, meaning "a lamentation; mournful complaint,"[81] or further, "a cautionary or angry harangue."[82]

Jeremiah has periodically been a popular first name in the United States, beginning with the early Puritan settlers, who often took the names of Biblical prophets and apostles. In Ireland, Jeremiah was used to "translate" the Irish name Diarmuid.

Notes

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 383. ISBN 978-0-582-05383-0.) entry "Jeremiah"

- ^ Jeremiah, New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, Wheaton, IL, USA 1987.

- ^ ’’Lamentations’’, The Anchor Bible, commentary by Delbert R. Hillers, 1972, pp.XIX-XXIV

- ^ Hebrews 8:8-12 ESV Hebrews 10:16-17 ESV

- ^ The New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, 1982 p. 563; See also Jeremiah 31

- ^ a b Jeremiah 1-2

- ^ a b Jeremiah and Lamentations: From Sorrow to Hope, Philip Graham Ryken, R. Kent Hughes, 2001, pp.19-36

- ^ Jeremiah 5:19 ESV

- ^ Jeremiah 1:19 The Anchor Bible

- ^ Jeremiah 12:6

- ^ Jeremiah 20:1-4, See also The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan, 1995, p. 1501

- ^ Jeremiah 37:18, Jeremiah 38:28

- ^ Jeremiah 38:4

- ^ Jeremiah 38:6

- ^ Jeremiah 28

- ^ ’’Jeremiah, Lamentations’’, F.B. Huey, Broadman Press, 1993 pp. 433-439

- ^ Jeremiah 39:11-40:5

- ^ Jeremiah, chap. 1

- ^ Jeremiah 32:9

- ^ Jeremiah 8:18

- ^ "Who Weeps in Jeremiah VIII 23 (IX 1)? Identifying Dramatic Speakers in the Poetry of Jeremiah," Joseph M. Henderson, Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 52, Fasc. 2 (Apr., 2002), pp. 191-206

- ^ a b Jeremiah, Lamentations, Tremper Longman, Hendrickson Publishers, 2008, p. 6

- ^ (Jeremiah 1:1)

- ^ a b ’’Jeremiah (Prophet)’’, The Anchor Bible Dictionary Volume 3, Doubleday, 1992 p.686

- ^ (Jer.1)

- ^ (Jer.4)

- ^ Jer.2, Jer.3, Jer.5, Jer.9

- ^ (Jeremiah 19:4,5)

- ^ (Jer.10

- ^ 11)

- ^ seder hadorot year 3298

- ^ ’’Jeremiah’’, New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 pp. 559-560

- ^ ’’Introduction to Jeremiah’’, The Jewish Study Bible, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 917

- ^ ’’Jeremiah’’, New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 pp. 559-560

- ^ seder hadoroth, year 3350

- ^ 2 Kings 23:26-27

- ^ 2 Kings 23:32

- ^ Isaiah 6

- ^ Exodus 4:10-17

- ^ Jeremiah 1:6-9

- ^ Jeremiah 1:17 NIV

- ^ Jeremiah 1

- ^ Jeremiah 15:19

- ^ Jeremiah 16:2

- ^ Jeremiah 16:5

- ^ Jeremiah 16:8

- ^ Jeremiah 15:17

- ^ 2 Kings 22:8-10

- ^ a b c ’’Jeremiah (Prophet)’’, The Anchor Bible Dictionary Volume 3, Doubleday, 1992 p.687

- ^ Jeremiah 1:7

- ^ Jeremiah 3:12-23, Jeremiah 4:1-4

- ^ Jeremiah 6:13-14

- ^ Jeremiah 36:1-10

- ^ Jeremiah 11:18-2:6

- ^ Commentary on Jeremiah, The Jewish Study Bible, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 950

- ^ Jeremiah 20:7

- ^ Jeremiah 20:9

- ^ Jeremiah 6:13-15, Jeremiah 14:14-16, Jeremiah 23:9-40, Jeremiah 27-28, Lamentations 2:14

- ^ Commentary of Jeremiah, The NIV Study Bible, Zondervan, 1995, p. 1544

- ^ Jeremiah 38

- ^ Jeremiah 40

- ^ Jeremiah 43

- ^ Jeremiah 44

- ^ Isaiah 20

- ^ Ezekiel 4

- ^ All the Parables of the Bible, Herbert Lockyer, Zondervan, 1963, pp. 51-61

- ^ Jeremiah 19

- ^ Jeremiah 27-28

- ^ (Jeremiah 13:1–11)

- ^ (Jeremiah 13:12–14)

- ^ Jeremiah 15:1

- ^ Jeremiah 32

- ^ This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

- ^ Pesiqta, ed. Buber, xiii. 112a

- ^ Tabari, i, 646f.

- ^ http://www.ccel.org/fathers2/NPNF1-05/npnf1-05-44.htm#P6934_2648698

- ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ a b Michael D. Coogan, A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament (New York: Oxford, 2009), 300.

- ^ "Ancient Document Confirms Existence Of Biblical Figure". Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ^ John F. Hobbins (with details on Assyrian names by Charles Halton)

- ^ Webster's encyclopedic unabridged dictionary of the English language. New York: Portland House. 1989. p. 766. ISBN 978-0-517-68781-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ "jeremiad - Definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

References

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote The Bible?, Harper and Row, NY, USA, 1987.

- Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Prophets. HarperCollins Paperback, 1975. ISBN 978-0-06-131421-6

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

- Ackroyd, Peter R. (1968). Exile and Restoration: A Study of Hebrew Thought in the Sixth Century BC. Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

- Bright, John (1965). The Anchor Bible: Jeremiah (2nd ed.). New York: Doubleday.

- Meyer, F.B. (1980). Jeremiah, priest and prophet (Revised ed.). Fort Washington, PA: Christian Literature Crusade. ISBN 0-87508-355-2.

- Perdue, Leo G.; Kovacs, Brian W., eds. (1984). A Prophet to the nations : essays in Jeremiah studies. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-20-X.

- Rosenberg, Joel (1987). "Jeremiah and Ezekiel". In Alter, Robert; Kermode, Frank (eds.). The literary guide to the Bible. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-87530-3.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Download Lamentations with linear Hebrew and English and afterword, from neohasid.org

- History of ancient Israel and Judah