Julian Bond: Difference between revisions

m WP:CHECKWIKI error #48 + general fixes using AWB (8869) |

|||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

In January 2007, he delivered the annual Martin Luther King lecture at [[Siena College]]. |

In January 2007, he delivered the annual Martin Luther King lecture at [[Siena College]]. |

||

He is a strong critic of policies that contribute to anthropogenic [[climate change]] and was amongst a group of protesters arrested at the [[White House]] for civil disobedience in opposition to the Keystone XL pipline in February 2013.<ref>http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/courts_law/sierra-club-leader-to-risk-arrest-in-protest-against-keystone-xl-oil-pipeline/2013/02/13/86d23d00-75ce-11e2-9889-60bfcbb02149_story.html</ref> |

|||

== Personal life == |

== Personal life == |

||

Revision as of 18:43, 14 February 2013

Julian Bond | |

|---|---|

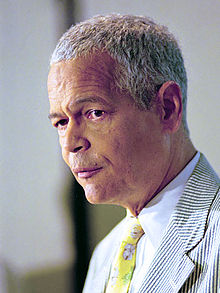

Julian Bond (Jim Wallace, 2001) | |

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives from the 32nd district | |

| In office 1967–1974 | |

| Succeeded by | Mildred Glover[1] |

| Member of the Georgia Senate from the 39th district | |

| In office 1975–1987 | |

| Preceded by | Horace T. Ward[2] |

| Succeeded by | Hildred W. Shumake[3] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Horace Julian Bond January 14, 1940 Nashville, Tennessee, USA |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Alice Clopton (1961–1989, divorced) Pamela S. Horowitz (1990–present) |

| Alma mater | George School Morehouse College (BA, English, 1971) |

Horace Julian Bond (born January 14, 1940), known as Julian Bond, is an American social activist and leader in the American civil rights movement, politician, professor, and writer. While a student at Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, during the early 1960s, he helped to establish the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Bond was elected to four terms in the Georgia House of Representatives and later to six terms in the Georgia Senate, having served a combined twenty years in both legislative chambers. From 1998 to 2010, he was chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Early life and education

Julian Bond was born at Hubbard Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, to the former Julia Agnes Washington a graduate of Fisk University, and Horace Mann Bond a prominent educator. At the time the family resided in on campus at Fort Valley State College where Horace Mann Bond was president. The house of the Bonds was a frequent stop for scholars and celebrities passing by such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. In 1945 his father was offered the position as the first African-American president of Lincoln University, and the family moved up North.[4]

In 1957, Bond graduated from George School, a private Quaker preparatory boarding school near Newtown in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.[5]

In 1960, Bond was a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and served as its communications director from 1961 to 1966. From 1960 to 1963, he led student protests against segregation in public facilities in Georgia. Bond left Morehouse in 1961 and returned to complete his BA in English in 1971 at age 31. With Morris Dees, Bond helped found the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), a public-interest law firm based in Montgomery, Alabama. He served as its president from 1971 to 1979. Bond continues on the board of directors of the SPLC.

Career

In 1965, Bond was one of eight African Americans elected to the Georgia House of Representatives after passage of civil rights legislation, including the Voting Rights Act of 1965. On January 10, 1966, however, Georgia state representatives voted 184-12 not to seat him because he publicly endorsed SNCC's policy regarding opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. They disliked Bond's stated sympathy for persons who were "unwilling to respond to a military draft".[6] A federal District Court panel ruled 2-1 that the Georgia House had not violated any of Bond's federal constitutional rights. In 1966, the United States Supreme Court ruled 9-0 in the case of Bond v. Floyd (385 U.S. 116) that the Georgia House of Representatives had denied Bond his freedom of speech and was required to seat him. From 1967 to 1975, Bond was elected for four terms as a Democratic member in the Georgia House. There he organized the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus.

In January 1967, Bond was among eleven House members who refused to vote when the legislature elected segregationist Lester Maddox of Atlanta as governor of Georgia over the Republican Howard Callaway, who had led in the 1966 general election by some three thousand votes. The choice fell on state lawmakers under the Georgia Constitution of 1824 because neither major party candidate had polled a majority in the general election. Former Governor Ellis Arnall polled more than fifty thousand votes as a write-in cadidate, a factor which led to the impasse. Bond would not support either Maddox or Callaway though he was ordered to vote by lame duck Lieutenant Governor Peter Zack Geer.[7]

Throughout his House career, Bond's district was repeatedly altered:

He went on to be elected for six terms in the Georgia Senate in which he served from 1975 to 1987.

During the 1968 presidential election, Bond led an alternate delegation from Georgia to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. There, unexpectedly and contrary to his intention, he became the first African American to be proposed as a major-party candidate for Vice President of the United States. While expressing gratitude for the honor, the 28-year-old Bond quickly declined, citing the constitutional requirement that one must be at least 35 years of age to serve in that office.

Bond resigned from the Georgia Senate in 1987 to run for the United States House of Representatives from Georgia's 5th congressional district. He lost the Democratic nomination in a runoff to rival civil rights leader John Lewis in a bitter contest, in which Bond was accused of using cocaine and other drugs.[11] As the 5th district had a huge Democratic majority, the nomination delivered the seat to Lewis, who still serves as congressman.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Bond taught at several universities in major cities of the North and South, including American, Drexel, Harvard, and the University of Virginia.

In 1998, Bond was selected as chairman of the NAACP. In November 2008, he announced that he would not seek another term as chairman.[12] Bond agreed to stay on in the position through 2009 as the organization celebrated its 100th anniversary. Roslyn M. Brock was chosen as Bond's successor on February 20, 2010.[13]

He continues to write and lecture about the history of the civil rights movement and the condition of African Americans and the poor. He is President Emeritus of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

From 1980 to 1997 he hosted America's Black Forum. He remains a commentator for the Forum, for radio's Byline, and for NBC's The Today Show. He authored the nationally syndicated newspaper column Viewpoint. He narrated the critically acclaimed PBS series Eyes on the Prize in 1987 and 1990.

Bond has been an outspoken supporter of the rights of gays and lesbians. He has publicly stated his support for same-sex marriage. Most notably he boycotted the funeral services for Coretta Scott King on the grounds that the King children had chosen an anti-gay megachurch. This was in contradiction to their mother's longstanding support for the rights of gay and lesbian people.[14] In a 2005 speech in Richmond, VA, Bond stated:

- African Americans ... were the only Americans who were enslaved for two centuries, but we were far from the only Americans suffering discrimination then and now. ... Sexual disposition parallels race. I was born this way. I have no choice. I wouldn’t change it if I could. Sexuality is unchangeable.[15]

In a 2007 speech on the Martin Luther King Day Celebration at Clayton State University in Morrow, GA, Bond said, "If you don't like gay marriage, don't get gay married." His positions have pitted elements of the NAACP against religious groups in the Black Civil Rights movement who oppose gay marriage mostly within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) who was blamed partly for the success of the recent gay marriage ban amendment in California.[citation needed]

Today, Bond is a Distinguished Professor in Residence at American University in Washington, D.C. He also is a faculty member in the history department at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville, where he teaches history of the Civil Rights Movement.[16]

In January 2007, he delivered the annual Martin Luther King lecture at Siena College.

He is a strong critic of policies that contribute to anthropogenic climate change and was amongst a group of protesters arrested at the White House for civil disobedience in opposition to the Keystone XL pipline in February 2013.[17]

Personal life

On July 28, 1961, Bond married Alice Clopton, a student at Spelman College. They divorced on November 10, 1989. They had five children: Phyllis Jane Bond-McMillan, Horace Mann Bond II, Michael Julian Bond, (an At-large member of Atlanta’s Council), Jeffrey Alvin Bond and Julia "Cookie" Louise Bond. He married Pamela S. Horowitz, an attorney, on March 17, 1990.

Legacy and honors

- 2002 - National Freedom Award

- In 1999, an honorary LL.D. from Bates College.

- In 2008, an honorary degree from George Washington University. Bond was the 2008 Commencement Keynote Speaker.[18]

- In 2009, he was awarded the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP.[19]

- On October 1, 2009, an honorary L.H.D. from Macalester College.

The above four are among 25 honorary degrees which he has been awarded.

Eyes on the Prize

Julian Bond was the narrator of the PBS video, Eyes on the Prize, recounting the civil rights controversies of the 1950s and 1960s.

Julian Bond: Reflection from the Civil Rights Movement

Julian Bond is the protagonist on Julian Bond: Reflections from the Frontlines of the Civil Rights Movement, a documentary film by Eduardo Montes-Bradley. Produced by the Heritage Film Project and distributed by the Filmakers Library.[20]

Controversial comments

As NAACP chairman, Bond strongly criticized the Republican Party. WorldNetDaily, a conservative Internet-based news service, which inaccurately reported Bond as saying: "[The Republicans'] idea of equal rights is the American flag and the Confederate swastika flying side-by-side." WorldNetDaily accused him of calling Secretary of State Rice and former Secretary Powell "tokens" and comparing the judicial nominees of President George W. Bush to the Taliban.[21] His actual words were that the Republican Party uses them "as kinds of human shields against any criticism of their record on civil rights."[22] The issue was resolved when the Fayetteville Observer reported on its review of the audio recordings of the speech.

Bond was a strong critic of the Bush administration from its assumption of office in 2001, in large part because Bond believed the administration was illegitimate. Twice that year, first in February to the NAACP board and then in July at that organization's national convention, he attacked the administration for selecting Cabinet secretaries "from the Taliban wing of American politics". Bond specifically targeted Attorney General John Ashcroft, who had opposed affirmative action, and Interior Secretary Gale Norton, who defended the Confederacy in a 1996 speech on states' rights. The selection of these two individuals, Bond said, "...whose devotion to the Confederacy is nearly canine in its uncritical affection", "appeased the wretched appetites of the extreme right wing". Then-House Majority Leader Dick Armey responded to Bond's statement with a letter accusing NAACP leaders of "racial McCarthyism."[23]

In 2003 Bond was quoted in a New York Times article criticizing the names of public schools named for Confederate leaders by saying, "If it had been up to Robert E. Lee, these kids wouldn't be going to school as they are today. They can't help but wonder about honoring a man who wanted to keep them in servitude."

Media appearances

During his tenure with the NAACP, Bond was frequently interviewed and appeared on numerous news shows. He also had a small appearance in the movie Ray (2004).

Bond hosted Saturday Night Live on April 9, 1977, becoming the first black political figure to host the show. The famous segment from this appearance is the "Black Perspective" skit with then-SNL cast member Garrett Morris. Bond explained perceptions of white and black IQ differences with the tongue-in-cheek "theory" that "light-skinned blacks are smarter than dark-skinned blacks."[24]

On October 11, 2009 Julian appeared at the National Equality March in Washington, D.C. and spoke upon the rights of LGBT community which was aired live on C-SPAN.[25][26]

Writings

- Black Candidates: Southern Campaign Experiences. Atlanta: Voter Education Project, Southern Regional Council, 1969.

- A Time To Speak, A Time To Act: The Movement in Politics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

- Gonna Sit at the Welcome Table: A Documentary History of the Civil Rights Movement. (with Andrew Lewis). American Heritage, 1995.

- Lift Every Voice and Sing: A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem, 100 Years, 100 Voices. (with Sondra Kathryn Wilson, eds.) New York: Random House, 2000.

- Nationally syndicated column Viewpoint.

- Poems and articles have appeared in a national list of magazines and newspapers.

- Julian Bond's papers reside at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

Further reading

References

- ^ "Members of Georgia House of Representatives alphabetically arranged according to names, with districts and post offices for the term 1974-1975", Acts and resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, vol. 1, Georgia Legislature, p. 2019, 1974

- ^ "Members of the Senate of Georgia by Districts in Numberical Order and Post Offices for the Term 1973-1974", Acts and Resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, vol. 1, p. 1671, 1973

- ^ "Members of Georgia House of Representatives for the term 1987-1988 by districts and addresses", Acts and resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, Georgia Legislature, p. CLXXIV

- ^ Denise M. Jordan. "Julian Bond" Enslow Publishers, Inc. Chapter II. P. 11,12,13

- ^ "Julian Bond: Reflections from the Civil Rights Movement" by Eduardo Montes Bradley. Filmakers Library. 2012 New York, USA

- ^ The World Almanac 1967, pp. 54–55

- ^ Billy Hathorn, "The Frustration of Opportunity: Georgia Republicans and the Election of 1966", Atlanta History: A Journal of Georgia and the South, XXXI (Winter 1987-1988), p. 47

- ^ Acts and resolutions, 1967, 1968

- ^ 1969-1970 house roster (page 1284)

- ^ [1]

- ^ Jet Magazine. 72 (5). Johnson Publishing Company: 54–55. 1987.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Bond won't seek re-election as NAACP Chairman". International Herald Tribune. 2008-11-18. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ^ "NAACP chooses successor to Chairman Julian Bond". CNN. 2010-02-20. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ Black Voices Q&A 09/25/06 http://www.blackvoices.com/black_news/canvas_directory_headlines_features/_a/bv-qanda-with-julian-bond/20060908115409990002

- ^ "NAACP chair says 'gay rights are civil rights'". Washington Blade. 2004-04-08. Archived from the original on March 21, 2006. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ^ http://www.american.edu/spa/faculty/hjb7g.cfm

- ^ http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/courts_law/sierra-club-leader-to-risk-arrest-in-protest-against-keystone-xl-oil-pipeline/2013/02/13/86d23d00-75ce-11e2-9889-60bfcbb02149_story.html

- ^ "NAACP chairman will speak at Commencement". The GW Hatchet. 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ NAACP Spingarn Medal

- ^ Filmakers Library | Alexander Street Press. Catalogue 2013. page 57.

- ^ WorldNetDaily: NAACP chairman compares GOP to Nazis

- ^ http://www.fayettevillenc.com/article?id=225894 [dead link]

- ^ Wickham, DeWayne (2001-07-16). "Julian Bond: Master needler" (Opinion). USA Today. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Julian Bond / Tom Waits". Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ^ Street vs. suite by Richard J. Rosendall. October 13, 2009. Bay Windows

- ^ C-Span archive

External links

- NAACP biography

- SPLC biography

- Julian Bond at IMDb

- Brief video clip From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

- Julian Bond at Answers.com

- Oral History Interview with Julian Bond from Oral Histories of the American South

- Faculty Profile

- Articles with dead external links from November 2008

- African-American politicians

- African Americans' rights activists

- African-American television personalities

- American columnists

- American television personalities

- American University faculty and staff

- Georgia (U.S. state) State Senators

- Members of the Georgia House of Representatives

- Morehouse College alumni

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

- People from Nashville, Tennessee

- Harvard University faculty

- University of Virginia faculty

- 1940 births

- Living people

- Spingarn Medal winners

- 20th-century African-American activists

- Southern Poverty Law Center

- Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats

- People from Bucks County, Pennsylvania