Peking Man

| Homo erectus pekinensis Temporal range: Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

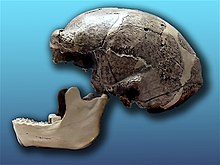

| First cranium of Homo erectus pekinensis (Sinathropus pekinensis) discovered in 1929 in Zhoukoudian, today missing (Replica) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | H. e. pekinensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus pekinensis (Black, 1927)

| |

Peking Man (Chinese: 北京猿人; pinyin: Běijīng Yuánrén), also called Sinanthropus pekinensis (currently Homo erectus pekinensis), is a separate species of Homo erectus, evolutionarily distinct from Homo Heidelbergensis and Homo Ergaster. A group of fossil specimens was discovered in 1923-27 during excavations at Zhoukoudian (Chou K'ou-tien) near Beijing (written 'Peking' before the adoption of the Pinyin romanization system), China. More recently, the finds have been dated from roughly 500,000 years ago,[1] although a new 26Al/10Be dating suggests they may be as much as 680,000-780,000 years old.[2][3]

Between 1929 and 1937, 15 partial craniums, 11 lower jaws, many teeth, some skeletal bones and large numbers of stone tools were discovered in the Lower Cave at Locality 1 of the Peking Man site at Zhoukoudian, near Beijing, in China. Their age is estimated to be between 500,000 and 300,000 years old. (A number of fossils of modern humans were also discovered in the Upper Cave at the same site in 1933.) The most complete fossils, all of which were braincases or skullcaps, are:

- Skull III, discovered at Locus E in 1929 is an adolescent or juvenile with a brain size of 915 cc.

- Skull II, discovered at Locus D in 1929 but only recognized in 1930, is an adult or adolescent with a brain size of 1030 cc.

- Skulls X, XI and XII (sometimes called LI, LII and LIII) were discovered at Locus L in 1936. They are thought to belong to an adult man, an adult woman and a young adult, with brain sizes of 1225 cc, 1015 cc and 1030 cc respectively. (Weidenreich 1937)

- Skull V: two cranial fragments were discovered in 1966 which fit with (casts of) two other fragments found in 1934 and 1936 to form much of a skullcap with a brain size of 1140 cc. These pieces were found at a higher level, and appear to be more modern than the other skullcaps. (Jia and Huang 1990)

Most of the study on these fossils was done by Davidson Black until his death in 1934. Franz Weidenreich replaced him and studied the fossils until leaving China in 1941. The original fossils disappeared in 1941 while being shipped to the United States for safety during World War II, but excellent casts and descriptions remain. Since the war, other erectus fossils have been found at this site[citation needed] and others in China.[citation needed]

The illustration above is of a reconstruction done by Franz Weidenreich, based on bones from at least four different individuals (none of the fossils were this complete).

Discovery and identification

Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson and American palaeontologist Walter W. Granger came to Zhoukoudian, China in search of prehistoric fossils in 1921. They were directed to the site at Dragon Bone Hill by local quarrymen, where Andersson recognised deposits of quartz that were not native to the area. Immediately realising the importance of this find he turned to his colleague and announced, "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"[4]

Excavation work was begun immediately by Andersson's assistant Austrian palaeontologist Otto Zdansky, who found what appeared to be a fossilised human molar. He returned to the site in 1923 and materials excavated in the two subsequent digs were sent back to Uppsala University in Sweden for analysis. In 1926 Andersson announced the discovery of two human molars found in this material and Zdansky published his findings.[5]

Canadian anatomist Davidson Black of Peking Union Medical College, excited by Andersson and Zdansky’s find, secured funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and recommenced excavations at the site in 1927 with both Western and Chinese scientists. A tooth was unearthed that fall by Swedish palaeontologist Anders Birger Bohlin which Davidson placed in a locket around his neck.

Davidson published his analysis in the journal Nature, identifying his find as belonging to a new species and genus which he named Sinanthropus pekinensis, but many fellow scientists were skeptical of such an identification based on a single tooth and the Foundation demanded more specimens before they would give an additional grant.[6]

A lower jaw, several teeth, and skull fragments were unearthed in 1928. Black presented these finds to the Foundation and was rewarded with an $80,000 grant that he used to establish the Cenozoic Research Laboratory.

Excavations at the site under the supervision of Chinese archaeologists Yang Zhongjian, Pei Wenzhong, and Jia Lanpo uncovered 200 human fossils (including 6 nearly complete skullcaps) from more than 40 individual specimens. These excavation came to an end in 1937 with the Japanese invasion.

Fossils of Peking Man were placed in the safe at the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the Peking Union Medical College. Eventually, in November 1941, secretary Hu Chengzi packed up the fossils so they could be sent to USA for safekeeping until the end of the war. They vanished en route to the port city of Qinhuangdao.

Various parties have tried to locate the fossils, but so far they have been without result. In 1972, a US financier Christopher Janus promised a $5,000 (USD) reward for the missing skulls; one woman contacted him, asking for $500,000 (USD) but she later vanished[citation needed]. In July 2005, the Chinese government founded a committee to find the bones to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II.

There are various theories of what might have happened, including a theory that the bones sank with the Japanese ship Awa Maru in 1945.[7] Three of the teeth can, however, be found at the Paleontological Museum of Uppsala University.[8]

Subsequent Research

Excavations at Zhoukoudian resumed after the war, and parts of another skull were found in 1966. To date a number of other partial fossil remains have been found. The Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1987.[9] New excavations were scheduled to start at the site in the middle of May 2009.[10]

Paleontological conclusions

The first specimens of Homo erectus had been found in Java in 1891 by Eugene Dubois, but were dismissed by many as the remains of a deformed ape. The discovery of the great quantity of finds at Zhoukoudian put this to rest and Java Man, who had initially been named Pithecanthropus erectus, was transferred to the genus Homo along with Peking Man.[11]

Contiguous findings of animal remains and evidence of fire and tool usage, as well as the manufacturing of tools, were used to support H. erectus being the first "faber" or tool-worker. The analysis of the remains of "Peking Man" led to the claim that the Zhoukoudian and Java fossils were examples of the same broad stage of human evolution.

This interpretation was challenged in 1985 by Lewis Binford, who claimed that the Peking Man was a scavenger, not a hunter. The 1998 team of Steve Weiner of the Weizmann Institute of Science concluded that they had not found evidence that the Peking Man had used fire.[citation needed]

Relation to modern Chinese people

Franz Weidenreich considered Peking Man as a human ancestor and specifically an ancestor of the Chinese people,[12] as seen in his original multiregional model of human evolution in 1946.[13] Chinese writings on human evolution in 1950 generally considered evidence insufficient to determine whether Peking Man was ancestral to modern humans. One view was that Peking Man in some ways resembled modern Europeans more than modern Asians.[14] By 1952, however, Peking Man had been considered both a direct ancestor of modern humans and a symbol of Chinese nationalism.[15] Paleontologists have noted a perceived continuity in skeletal remains.[16] Many Chinese paleoanthropologists have published scientific studies in the past showing both fossil and DNA evidence that the modern Chinese (and possibly other ethnic groups) are descendants of Peking Man, of which there both studies which support and refute this thesis. A previous study of around 10,000 individuals undertaken by Chinese geneticist Jin Li suggested that the genetic diversity of 10,000 Chinese test subjects is well within that of the whole world population, which attempts to suggest there was no inter-breeding between anatomically modern African Homo Sapien immigrants to East Asia and Homo erectus, such as Peking Man, and it alleges that the Chinese are descended from Africa, like all other modern humans, in accordance with the Recent single-origin hypothesis.[17][18][19] In contradiction, numerous genetic studies have shown strong support for an independent Chinese evolutionary origin and provide evidence that modern Chinese people have a genetic DNA remnant of a previous archaic form of human, Homo Pekinensis, indigenous to China. The RRM2P4 gene data suggests that some Chinese have genes descended from old archaic East Asian Homo Erectus populations, suggesting that, using a conservative estimate, a sub-population of the Chinese people may in fact be descended from the separate archaic species of Homo Erectus rather than anatomically modern African Homo Sapien, thus representing a more evolved anatomically modern form of Chinese Homo Pekinensis that has evolved a larger brain size in comparison with the archaic Homo Erectus. In addition, a tremendous amount of archaeological fossil evidence has been published in scientific journals supporting a separate evolutionary origin of the Chinese, of which some members of their population may or may not have interbred with anatomically modern African Homo Sapiens. All of the archaic East Asian Homo Pekinensis and Homo Erectus fossils studied have shown a continuity of unique morphological and anatomical traits, such as small frontal sinuses, reduced posterior teeth, shovel-shaped incisors, and high frequencies of metopic sutures, which are virtually absent in modern day European, Middle Eastern, and African populations but widely present in the modern population of the Han Chinese.[20][21]This lends support to the multiregional evolution with a recent outside influx of Homo Sapien genetics]] and subsequent interbreeding between African Homo Sapiens and anatomically modern Chinese Homo Erectus resulting in a small fraction of the population of China incorporating some African Homo Sapien genes. In addition, some paleontologists and anthropologists have identified morphological similarities in both archaic Homo Erectus and modern Han Chinese people such as cranial skull shape, prominent cheek bones, shovel shaped incisors which are unique to the Chinese population and virtually absent in other humans with rare exceptions. These scientific findings suggest a continuity in the evolution of modern Chinese from archaic Homo Erectus rather than African Homo Sapien.[22] Genetic DNA evidence supporting a separate independent evolution of the modern Chinese people has been published in numerous peer reviewed scientific publications such as Oxford University's Oxford Journals, Evidence for Archaic Asian Ancestry on the Human X Chromosome by Daniel Garrigan, Zahra Mobasher, Tesa Severson, Jason A. Wilder and Michael F. Hammer and the Genetics Society of America's Genetics Journal, "Testing for Archaic Hominin Admixture on the X Chromosome: Model Likelihoods for the Modern Human RRM2P4 Region From Summaries of Genealogical Topology Under the Structured Coalescent" by Murray P. Cox, Fernando L. Mendez, Tatiana M. Karafet, Maya Metni Pilkington, Sarah B. Kingan, Giovanni Destro-Bisol, Beverly I. Strassmann and Michael F. Hammer as well as BMC Biology Journal of Biology "Y chromosome evidence of earliest modern human settlement in East Asia and multiple origins of Tibetan and Japanese populations" by Shi H, Zhong H, Peng Y, Dong YL, Qi XB, Zhang F, Liu LF, Tan SJ, Ma RZ, Xiao CJ, Wells RS, Jin L, Su B.

See also

- Zhoukoudian

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- List of hominina (hominid) fossils (with images)

- Human evolution

Further reading

- Jia, Lanpo, Huang, Weiwen. The Story of Peking Man: From Archaeology to Mystery. Oxford University Press, USA, 1990.

- Sautman, B. “Peking man and the politics of paleoanthropological nationalism in China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 60, no. 1 (2001): 95-124.

- Schmalzer, Sigrid, The People's Peking Man: Popular Science and Human Identity in Twentieth-Century China. The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Wu, R., and S. Lin. “Peking Man.” Scientific American 248, no. 6 (1983): 86-94.

- Jake Hooker - The Search for the Peking Man Archaeology magazine March/April 2006)

References

- ^ Ian Tattersall. "Out of Africa again...and again?". Scientific American. 276 (4): 60–68.

- ^ Shen, G; Gao, X; Gao, B; Granger, De (2009). "Age of Zhoukoudian Homo erectus determined with (26)Al/(10)Be burial dating". Nature. 458 (7235): 198–200. doi:10.1038/nature07741. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19279636.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "'Peking Man' older than thought". BBC News. 2009-03-11. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

In the summer of 1921, Dr. J.G. Andersson and his companions discovered this richly fossiliferous deposit through the local quarry men's guide. During examination he was surprised to notice some fragments of white quartz in tabus, a mineral normally foreign in that locality. The significance of this occurrence immediately suggested itself to him and turning to his companions, he exclaimed dramatically "Here is primitive man, now all we have to do is find him!"

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The First Knock at the Door". Peking Man Site Museum.

For some weeks in this summer and a longer period in 1923 Dr. Otto Zdansky carried on excavations of this cave site. He accumulated an extensive collection of fossil material, including two Homo erectus teeth that were recognized in 1926. So, the cave home of Peking Man was opened to the world.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Morgan Lucas" (PDF).

- ^ "Sinking and salvage of the Awa Maru" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.vethist.idehist.uu.se/Newsletter_pdf/NewsL_37.pdf

- ^ "Unesco description of the Zhoukoudian site".

- ^ Xinhua article, 4 May 2009

- ^ Melvin, Sheila (October 11, 2005). "Archaeology: Peking Man, still missing and missed". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

The discovery also settled a controversy as to whether the bones of Java Man - found in 1891 - belonged to a human ancestor. Doubters had argued that they were the remains of a deformed ape, but the finding of so many similar fossils at Dragon Bone Hill silenced such speculation and became a central element in the modern interpretation of human evolution.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Schmalzer, pg 98.

- ^ Template:Cite jornal

- ^ Zhu Xi, Women de zuxian [Our Ancestors] (Shanghai: Wen hua shenghuo chubanshe, 1950 [1940]), 163. (reference by Schmalzer, pg 97)

- ^ Schmalzer, pg 97.

- ^ Shang; et al. (1999). "An early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (16): 6573. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702169104. PMID 17416672.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Jin; et al. (1999). "Distribution of haplotypes from a chromosome 21 region distinguishes multiple prehistoric human migrations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (7): 3796. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3796. PMID 10097117.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "multiregional or single origin".

- ^ "mapping human history p130-131".

- ^ sequence and gene tree for RRM2P4 haplotypes oxfordjournals.org

- ^ Garrigan, D; Mobasher, Z; Severson, T; Wilder, Ja; Hammer, Mf (2005). "Evidence for archaic Asian ancestry on the human X chromosome" (Free full text). Molecular biology and evolution. 22 (2): 189–92. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi013. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 15483323.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shang; et al. (1999). "An early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, Zhoukoudian, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (16): 6573. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702169104. PMID 17416672.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)