Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution: Difference between revisions

clar |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

=== Slavery in the United States === |

=== Slavery in the United States === |

||

[[Image:Cicatrices de flagellation sur un esclave.jpg|thumb|Abolitionist imagery focused on atrocities against slaves.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kenneth M. Stampp|title=The Imperiled Union:Essays on the Background of the Civil War|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=J6I87GxnOBEC&pg=PA85|year=1980|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=85}}</ref> (1863 photo)]] |

[[Image:Cicatrices de flagellation sur un esclave.jpg|thumb|Abolitionist imagery focused on atrocities against slaves.<ref>{{cite book|author=Kenneth M. Stampp|title=The Imperiled Union:Essays on the Background of the Civil War|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=J6I87GxnOBEC&pg=PA85|year=1980|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=85}}</ref> (1863 photo)]] |

||

Slavery existed in every colony. The [[United States Constitution]] of 1787 did not use the word "slavery" but included several provisions about unfree persons. The [[Three-Fifths Compromise]] (in Article I, Section 2) allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three fifths of all other Persons".<ref>{{cite book|author=Jean Allain|title=The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=n_KAvAjkEbsC&pg=PA117|year=2012|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=117}}</ref> The [[Fugitive Slave Clause]] (Article IV, Section 2) "no person held to service or labour in one state" would be freed by escaping to another. [[Article_One_of_the_United_States_Constitution#Section_9:_Limits_on_Congress|Article I, Section 9]] allowed Congress to pass legislation to outlaw the "Importation of Persons", but not before after 1807. |

Slavery existed in every colony. The [[United States Constitution]] of 1787 did not use the word "slavery" but included several provisions about unfree persons. The [[Three-Fifths Compromise]] (in Article I, Section 2) allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three fifths of all other Persons".<ref>{{cite book|author=Jean Allain|title=The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=n_KAvAjkEbsC&pg=PA117|year=2012|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=117}}</ref> The [[Fugitive Slave Clause]] (Article IV, Section 2) "no person held to service or labour in one state" would be freed by escaping to another. [[Article_One_of_the_United_States_Constitution#Section_9:_Limits_on_Congress|Article I, Section 9]] allowed Congress to pass legislation to outlaw the "Importation of Persons", but not before after 1807.<ref name="Foner—2010——16">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 16</ref> However, for purposes of the [[Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fifth Amendment]]—which states that "No person shall... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood as property.<ref>{{cite book|author=Jean Allain|title=The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=n_KAvAjkEbsC&pg=PA119|year=2012|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=119–120}}</ref> Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it became part of the legal basis for treating slaves as property with ''[[Dred Scott v. Sanford]]''.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 14. "Nineteenth century apologists for the expansion of slavery developed a political philosophy that placed property at the pinnacle of personal interests and regarded its protection to be the government's chief purpose. The Fifth Amendment's Just Compensation clause provided the proslavery camp with a bastion for fortifying the peculiar institution against congressional restrictions to its spread westward. Based on this property-rights centered argument, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, in his infamous ''Dred Scott v. Sanford'' (1857), found the Missouri Compromise unconstitutionally violated due process."</ref> Slavery was supported in practice by a pervasive culture of [[white supremacy]].<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 18–23. "Constitutional protections of slavery coexisted with an entire culture of oppression. The peculiar institution reached many private aspects of human life, for both whites and blacks. [...] Even free Southern blacks lived in a world so legally constricted by racial domination that it offered only a deceptive shadow of freedom."</ref> |

||

Between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861. |

Between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861.<ref name="Foner—2010——14&ndash;16">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], pp. 14–16</ref> An [[abolitionist]] movement headed by such figures as [[William Lloyd Garrison]] grew in strength in the North, calling for the end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating sectional tensions. In 1836, the US [[House of Representatives]] instituted a [[gag rule]] against abolitionist petitions and speeches, attempting to stifle [[John Quincy Adams]] and other abolitionist congressmen. The [[American Colonization Society]], in contrast, called for the emigration and colonization of African American slaves, who were freed, to Africa; its views were endorsed by politicians such as [[Henry Clay]], who feared that the abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war.<ref name="Foner—2010——20&ndash;22">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], pp. 20–22</ref> Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative [[Arthur Livermore]] in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.<ref name="Vile">{{cite encyclopedia |year=2003 |title =Thirteenth Amendment |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues: 1789 - 2002 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |editor-first=John R. |editor-last=Vile |pages=449–52 }}</ref> |

||

As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property. |

As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——123">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 123</ref> The 1820 [[Missouri Compromise]] provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the Senate's equality between the regions. In 1846, the [[Wilmot Proviso]] was introduced to a war appropriations bill to ban slavery in all territories acquired in the [[Mexican–American War]]; the Proviso repeatedly passed the House, but not the Senate.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——123">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 123</ref> The [[Compromise of 1850]] temporarily defused the issue by admitting California as a free state, instituting a stronger [[Fugitive Slave Act of 1850|Fugitive Slave Act]], banning the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and allowing New Mexico and Utah self-determination on the slavery issue.<ref name="Foner—2010——59">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 59</ref> |

||

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel ''[[Uncle Tom's Cabin]]''; |

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel ''[[Uncle Tom's Cabin]]'';<ref name="McPherson—1988——88&ndash;91">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], pp. 88–91</ref> [[Bleeding Kansas|fighting between pro-slave and abolitionist forces]] in Kansas, beginning in 1854;<ref name="McPherson—1988——146&ndash;50">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], pp. 146–50</ref> the 1857 [[Dred Scott decision]] by the [[US Supreme Court]], which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850;<ref name="McPherson—1988——170&ndash;77">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], pp. 170–77</ref> abolitionist [[John Brown (abolitionist)|John Brown]]'s 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at [[John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry|Harpers Ferry]];<ref name="McPherson—1988——201&ndash;06">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], pp. 201–06</ref> and the 1860 election of the anti-slavery Republican candidate [[Abraham Lincoln]] to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the [[Confederate States of America]] and beginning the [[American Civil War]].<ref name="McPherson—1988——234&ndash;35">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], pp. 234–35</ref> |

||

=== Earlier proposed amendments === |

=== Earlier proposed amendments === |

||

Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, no [[List of amendments to the United States Constitution|constitutional amendments]] had been adopted in more than 60 years. Two earlier amendments proposed by the Congress would have become the Thirteenth Amendment, but failed to be ratified by a sufficient number of states. The first, the [[Titles of Nobility Amendment]], was proposed by the Congress in 1810 and ratified by twelve states. It would have revoked the citizenship of anyone accepting any foreign payment without Congressional authorization or accepting a foreign title of nobility.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|year=2009|title=Titles of Nobility|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of the United States Constitution|publisher=Infobase|last=Mark W. Podvia|editor-first=David Andrew Schultz|pages=738–39|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=f7m713xwK58C&pg=PA739&dq=%22Titles+of+Nobility%22+1810&hl=en&sa=X&ei=lguuUYfrJ9Kj4APRqYGwDA&ved=0CEMQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=%22Titles%20of%20Nobility%22%201810&f=false}}</ref> |

Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, no [[List of amendments to the United States Constitution|constitutional amendments]] had been adopted in more than 60 years. Two earlier amendments proposed by the Congress would have become the Thirteenth Amendment, but failed to be ratified by a sufficient number of states. The first, the [[Titles of Nobility Amendment]], was proposed by the Congress in 1810 and ratified by twelve states. It would have revoked the citizenship of anyone accepting any foreign payment without Congressional authorization or accepting a foreign title of nobility.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|year=2009|title=Titles of Nobility|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of the United States Constitution|publisher=Infobase|last=Mark W. Podvia|editor-first=David Andrew Schultz|pages=738–39|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=f7m713xwK58C&pg=PA739&dq=%22Titles+of+Nobility%22+1810&hl=en&sa=X&ei=lguuUYfrJ9Kj4APRqYGwDA&ved=0CEMQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=%22Titles%20of%20Nobility%22%201810&f=false}}</ref> |

||

The second, the [[Corwin Amendment]], would have forbidden the adopting of any constitutional amendment abolishing or restricting slavery, or permitting the Congress to do so. Originally drafted by Abraham Lincoln's future [[Secretary of State]], [[William H. Seward]], and put forward by Senator [[Thomas Corwin]] of Ohio, this proposal was an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the [[Border states (American Civil War)|border states]] not to secede from the Union. In [[Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address|Lincoln's first inaugural address]], he stated that he had "no objection" to the amendment, as he believed that its provisions were already implied in the Constitution.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp|title=First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln|publisher=The Avalon Project|author=Abraham Lincoln|accessdate=November 30, 2012}}</ref> |

The second, the [[Corwin Amendment]], would have forbidden the adopting of any constitutional amendment abolishing or restricting slavery, or permitting the Congress to do so. Originally drafted by Abraham Lincoln's future [[Secretary of State]], [[William H. Seward]], and put forward by Senator [[Thomas Corwin]] of Ohio, this proposal was an unsuccessful attempt to persuade the [[Border states (American Civil War)|border states]] not to secede from the Union. In [[Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address|Lincoln's first inaugural address]], he stated that he had "no objection" to the amendment, as he believed that its provisions were already implied in the Constitution.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln1.asp|title=First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln|publisher=The Avalon Project|author=Abraham Lincoln|accessdate=November 30, 2012}}</ref><ref name="Foner—2010——156">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 156</ref> The amendment was passed by the House on February 28, 1861 and the Senate on March 2, 1861, but was ratified only by Ohio, Illinois, and Maryland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/HubPages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=02CorwinAmend|title=13th Amendment Site|publisher=13thamendment.harpweek.com|accessdate=November 30, 2012}}</ref><ref name="Foner—2010——158">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 158</ref> |

||

== Proposal by Congress == |

== Proposal by Congress == |

||

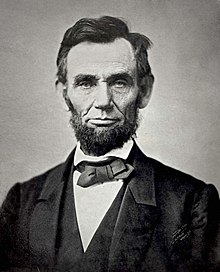

[[File:Abraham Lincoln November 1863.jpg|thumb|President [[Abraham Lincoln]] helped to push the proposed Amendment through Congress.]] |

[[File:Abraham Lincoln November 1863.jpg|thumb|President [[Abraham Lincoln]] helped to push the proposed Amendment through Congress.]] |

||

Acting under presidential war powers, Lincoln issued an [[Emancipation Proclamation]] on January 1, 1863, declaring all slaves in rebel-controlled territory to be free; the proclamation did not affect the status of slaves in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union. |

Acting under presidential war powers, Lincoln issued an [[Emancipation Proclamation]] on January 1, 1863, declaring all slaves in rebel-controlled territory to be free; the proclamation did not affect the status of slaves in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union.<ref name="McPherson—1988——558">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], p. 558</ref> Lincoln and others feared that the proclamation might be reversed or found invalid after the war, however, and sought more permanent guarantees that the freed blacks would not be re-enslaved.<ref name="Foner—2010——312&ndash;14">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], pp. 312–14</ref><ref name="Donald—1996——396">[[#CITEREFDonald1996|Donald, 1996]], p. 396</ref> |

||

In the final years of the Civil War, several legislative proposals were made to abolish slavery nationally and permanently by constitutional amendment. On December 14, 1863, a bill proposing such an amendment was introduced by Representative [[James Mitchell Ashley]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]], Ohio).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=129|title=James Ashley|work=Ohio History Central|publisher=Ohio Historical Society|accessdate=December 4, 2012}}</ref> This was soon followed by a similar proposal made by Representative [[James F. Wilson]] (Republican, Iowa). On January 11, 1864, Senator [[John B. Henderson]] of Missouri, one of the [[War Democrat]]s, submitted a [[joint resolution]] for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The [[United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary|Senate Judiciary Committee]], chaired by [[Lyman Trumbull]] (Republican, Illinois), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. |

In the final years of the Civil War, several legislative proposals were made to abolish slavery nationally and permanently by constitutional amendment. On December 14, 1863, a bill proposing such an amendment was introduced by Representative [[James Mitchell Ashley]] ([[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]], Ohio).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=129|title=James Ashley|work=Ohio History Central|publisher=Ohio Historical Society|accessdate=December 4, 2012}}</ref> This was soon followed by a similar proposal made by Representative [[James F. Wilson]] (Republican, Iowa). On January 11, 1864, Senator [[John B. Henderson]] of Missouri, one of the [[War Democrat]]s, submitted a [[joint resolution]] for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The [[United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary|Senate Judiciary Committee]], chaired by [[Lyman Trumbull]] (Republican, Illinois), became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment. |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

[[Radical Republicans]] led by Senator [[Charles Sumner]] and Representative [[Thaddeus Stevens]] sought a more expansive version of the Amendment.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), (2001), pp. 38–42.</ref> On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment to declare all Americans "equal before the law" as well as abolish slavery.<ref name="SocietyCommission1901">{{cite book|author=Michigan State Historical Society|title=Historical collections|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Yx0zAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA582|accessdate=December 5, 2012|year=1901|publisher=Michigan Historical Commission|page=582}}</ref> On February 10 the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal based on drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.<ref>[http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/hubpages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05ProposalPassage "Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage"], ''Harpers Weekly'', ''The Creation of the 13th Amendment'', Retrieved Feb 15, 2007</ref><ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), p. 53. "It was no coincidence that Trumbull's announcement came only two days after Sumner had proposed his amendment making all persons 'equal before the law.' The Massachusetts senator had spurred the committee into final action."</ref> The text of the Amendment's first section mirrored that of the [[Northwest Ordinance]] of 1787, which stipulates (for territories in the region now called the [[Midwest]]): “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”<ref>McAward, "McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), p. 1786</ref> |

[[Radical Republicans]] led by Senator [[Charles Sumner]] and Representative [[Thaddeus Stevens]] sought a more expansive version of the Amendment.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), (2001), pp. 38–42.</ref> On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment to declare all Americans "equal before the law" as well as abolish slavery.<ref name="SocietyCommission1901">{{cite book|author=Michigan State Historical Society|title=Historical collections|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Yx0zAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA582|accessdate=December 5, 2012|year=1901|publisher=Michigan Historical Commission|page=582}}</ref> On February 10 the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal based on drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.<ref>[http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/hubpages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05ProposalPassage "Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage"], ''Harpers Weekly'', ''The Creation of the 13th Amendment'', Retrieved Feb 15, 2007</ref><ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), p. 53. "It was no coincidence that Trumbull's announcement came only two days after Sumner had proposed his amendment making all persons 'equal before the law.' The Massachusetts senator had spurred the committee into final action."</ref> The text of the Amendment's first section mirrored that of the [[Northwest Ordinance]] of 1787, which stipulates (for territories in the region now called the [[Midwest]]): “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”<ref>McAward, "McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), p. 1786</ref> |

||

The Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6. However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to do so, with 93 in favor and 65 against, thirteen votes short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage; the vote split largely along party lines, with Republicans supporting and Democrats opposing. |

The Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6. However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to do so, with 93 in favor and 65 against, thirteen votes short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage; the vote split largely along party lines, with Republicans supporting and Democrats opposing.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——686">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 686</ref> In the 1864 presidential race, former [[Free Soil Party]] candidate [[John C. Frémont]] threatened a third party run opposing Lincoln, this time on a platform endorsing an anti-slavery amendment. The Republican Party platform had failed to include a similar plank, though Lincoln endorsed the amendment in a letter accepting his nomination.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——624&ndash;25">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], pp. 624–25</ref><ref name="Foner—2010——299">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 299</ref> Fremont withdrew from the race on September 22, 1864.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——639">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 639</ref> |

||

In November 1864, Lincoln was re-elected, and Republicans made substantial gains in Congress. Lincoln made the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment his top legislative priority in 1865, beginning his efforts while the "lame duck" session was still in office. |

In November 1864, Lincoln was re-elected, and Republicans made substantial gains in Congress. Lincoln made the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment his top legislative priority in 1865, beginning his efforts while the "lame duck" session was still in office.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——686&ndash;87">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], pp. 686–87</ref> Opposition to the measure was led by the 1864 Democratic vice presidential nominee, Representative [[George H. Pendleton]].<ref name="Goodwin—2005——688">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 688</ref> Democrats who opposed the Amendment generally made arguments based on [[federalism]] and [[state's rights]]. Said Rep. [[Joseph K. Edgerton]], it would be better "that negro slavery exist a thousand years than that American white men lose their constitutional liberty in the extinction of the constitutional sovereignty of the Federal States of this Union.”<ref>Benedict, "Constitutional Politics, Constitutional Law, and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), p. 179.</ref> Some argued that the proposed change so violated the spirit of the Constitution that it would not be a valid "amendment" but would instead constitute "revolution".<ref>Benedict, "Constitutional Politics, Constitutional Law, and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), p. 179–180. Benedict quotes Sen. [[Garrett Davis]]: "there is a boundary between the power of revolution and the power of amendment, which the latter, as established in our Constitution, cannot pass; and that if the proposed change is revolutionary it would be null and void, notwithstanding it might be formally adopted." Full text of Davis's speech, with comments from others can be found in ''[http://www.archive.org/stream/greatdebatesina17millgoog/greatdebatesina17millgoog_djvu.txt Great Debates in American History]'' (1918), ed. Marion Mills Miller.</ref> Republicans argued that slavery was uncivilized and that abolition was a necessary step in national progress.<ref>Benedict, "Constitutional Politics, Constitutional Law, and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), p. 182.</ref> |

||

Secretary of State Seward, Representative [[John B. Alley]] and others were instructed by Lincoln to procure votes by any means necessary, and promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides. |

Secretary of State Seward, Representative [[John B. Alley]] and others were instructed by Lincoln to procure votes by any means necessary, and promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides.<ref name="Foner—2010——312&ndash;13">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], pp. 312–13</ref><ref name="Goodwin—2005——687">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 687</ref> Ashley, who reintroduced the measure into the House, also lobbied several Democrats to vote in favor of the measure.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——687&ndash;689">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], pp. 687–689</ref> Representative [[Thaddeus Stevens]] commented later that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.<ref name="Donald—1996——554">[[#CITEREFDonald1996|Donald, 1996]], p. 554</ref> |

||

On January 31, 1865, the House called another vote on the amendment, with neither side being certain of the outcome. Every Republican supported the measure, as well as 16 Democrats, almost all of them lame ducks. The amendment finally passed by a vote of 119 to 56, narrowly reaching the required two-thirds majority. |

On January 31, 1865, the House called another vote on the amendment, with neither side being certain of the outcome. Every Republican supported the measure, as well as 16 Democrats, almost all of them lame ducks. The amendment finally passed by a vote of 119 to 56, narrowly reaching the required two-thirds majority.<ref name="Foner—2010——313">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 313</ref> The House exploded into celebration, with some members openly weeping;<ref name="Foner—2010——314">[[#CITEREFFoner2010|Foner, 2010]], p. 314</ref> black onlookers, who had only been allowed to attend Congressional sesions since the previous year, cheered from the galleries.<ref name="McPherson—1988——840">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], p. 840</ref> [[Secretary of War]] [[Edwin M. Stanton]] ordered three sets of one hundred guns to fire as he read the list of those who had voted in support of the amendment.<ref name="Goodwin—2005——689">[[#CITEREFGoodwin2005|Goodwin, 2005]], p. 689</ref> |

||

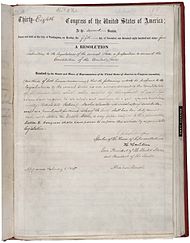

Lincoln signed the Amendment on February 1, 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified Amendment signed by a President; however, [[James Buchanan]] had signed the failed pro-slavery Corwin Amendment in 1861.<ref>Harrison, “Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments” (2001), p. 389. "For reasons that have never been entirely clear, the amendment was presented to the President pursuant to Article I, Section 7, of the Constitution, and signed.</ref><ref>Thorpe, ''Constitutional History'' (1901), p. 154. "The President signed the joint resolution on the first of February. Somewhat curiously the signing has only one precedent, and that was in spirit and purpose the complete antithesis of the present act. President Buchanan had signed the proposed Amendment of 1861, which would make slavery national and perpetual."</ref> The Thirteenth Amendment's archival copy bears Lincoln's signature, under the usual ones of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, and after the date.<ref>{{cite web|title=Joint Resolution Submitting 13th Amendment to the States; signed by Abraham Lincoln and Congress|work=The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 3. General Correspondence. 1837-1897|publisher=Library of Congress|url=http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mal&fileName=mal3/436/4361100/malpage.db&recNum=0}}</ref> On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary.<ref>Thorpe, ''Constitutional History'' (1901), p. 154. "But many held that the President's signature was not essential to an act of this kind, and, on the fourth of February, Senator Trumbull offered a resolution, which was agreed to three days later, that the approval was not required by the Constitution; "that it was contrary to the early decision of the Senate and of the Supreme Court; and that the negative of the President applying only to the ordinary cases of legislation, he had nothing to do with propositions to amend the Constitution."</ref> (Lincoln had already signed at least 14 commemorative copies of the document; these now sell for $1.8 million or more.)<ref>Tammy Webber, "[http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2011/12/06/lincoln_signed_copy_of_13th_amendment_restored/ Lincoln-signed copy of 13th Amendment restored]", ''Boston Globe'' (Associated Press), 6 December 2011.</ref> |

Lincoln signed the Amendment on February 1, 1865. The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified Amendment signed by a President; however, [[James Buchanan]] had signed the failed pro-slavery Corwin Amendment in 1861.<ref>Harrison, “Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments” (2001), p. 389. "For reasons that have never been entirely clear, the amendment was presented to the President pursuant to Article I, Section 7, of the Constitution, and signed.</ref><ref>Thorpe, ''Constitutional History'' (1901), p. 154. "The President signed the joint resolution on the first of February. Somewhat curiously the signing has only one precedent, and that was in spirit and purpose the complete antithesis of the present act. President Buchanan had signed the proposed Amendment of 1861, which would make slavery national and perpetual."</ref> The Thirteenth Amendment's archival copy bears Lincoln's signature, under the usual ones of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, and after the date.<ref>{{cite web|title=Joint Resolution Submitting 13th Amendment to the States; signed by Abraham Lincoln and Congress|work=The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 3. General Correspondence. 1837-1897|publisher=Library of Congress|url=http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mal&fileName=mal3/436/4361100/malpage.db&recNum=0}}</ref> On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary.<ref>Thorpe, ''Constitutional History'' (1901), p. 154. "But many held that the President's signature was not essential to an act of this kind, and, on the fourth of February, Senator Trumbull offered a resolution, which was agreed to three days later, that the approval was not required by the Constitution; "that it was contrary to the early decision of the Senate and of the Supreme Court; and that the negative of the President applying only to the ordinary cases of legislation, he had nothing to do with propositions to amend the Constitution."</ref> (Lincoln had already signed at least 14 commemorative copies of the document; these now sell for $1.8 million or more.)<ref>Tammy Webber, "[http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2011/12/06/lincoln_signed_copy_of_13th_amendment_restored/ Lincoln-signed copy of 13th Amendment restored]", ''Boston Globe'' (Associated Press), 6 December 2011.</ref> |

||

==Ratification== |

==Ratification== |

||

[[Image:13th amendment ratification.svg|thumb|400px|right| |

[[Image:13th amendment ratification.svg|thumb|400px|right|{{Legend|#0050ff|Ratified amendment, 1865}} |

||

{{Legend|#0050ff|Ratified amendment, 1865}} |

|||

{{legend|#00ff74|Ratified amendment post-enactment, 1865–1870}} |

{{legend|#00ff74|Ratified amendment post-enactment, 1865–1870}} |

||

{{legend|#d500ff|Ratified amendment after first rejecting amendment, 1866–1995}} |

{{legend|#d500ff|Ratified amendment after first rejecting amendment, 1866–1995}} |

||

| Line 55: | Line 54: | ||

The amendment was sent to the state legislatures. Most Northern states quickly ratified it, the only exceptions being those won by Democratic candidate [[George McClellan]] in the 1864 election: Delaware, Kentucky, and New Jersey. |

The amendment was sent to the state legislatures. Most Northern states quickly ratified it, the only exceptions being those won by Democratic candidate [[George McClellan]] in the 1864 election: Delaware, Kentucky, and New Jersey. |

||

The war had not officially ended, and the legal status of the defeated Southern states (and by extension, the legal requirements for Constitutional amendment) remained ambiguous Nevertheless, ratifications from Reconstruction governments in the Southern states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Virginia, and Tennessee were submitted and accepted. |

The war had not officially ended, and the legal status of the defeated Southern states (and by extension, the legal requirements for Constitutional amendment) remained ambiguous Nevertheless, ratifications from Reconstruction governments in the Southern states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Virginia, and Tennessee were submitted and accepted.<ref name="McPherson—1988——840">[[#CITEREFMcPherson1988|McPherson, 1988]], p. 840</ref><ref>Harrison, “Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments” (2001), p. 390. "Those ratifications raised some tricky questions. Four of them came from organizations purporting to be the legislatures of Virginia, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas. What about them? How many states were there, how many of them had legally valid legislatures, and if there were fewer legislatures than states, did Article V require ratification by three-fourths of the states or three-fourths of the legally valid state legislatures?"</ref> |

||

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln [[Assassination of Abraham Lincoln|was assassinated]] by [[John Wilkes Booth]]. With Congress out of session, Lincoln's successor [[Andrew Johnson]] began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new governments in seven Southern states (North Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, Alabama, South Carolina, and Florida). Johnson established political conventions populated by delegates he had approved; he strongly encouraged these conventions to ratify the amendment (and also repeal their states' ordinances of secession).<ref>Harrison, "Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments" (2001), p. 394–397. "Then came the kicker: The President decided who was loyal, prescribing suffrage qualifications for electing the convention. [...] Pursuant to Johnson's proclamations, the provisional governors organized elections for conventions. Six met in 1865, while Texas's convention did not organize until March 1866. Three leading issues came before the convention: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt."</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Eric L. McKitrick|title=Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=MqL8lmT74HEC&pg=PA178|year=1960|publisher=U. Chicago Press|page=178|isbn=9780195057072}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Clara Mildred Thompson|title=Reconstruction in Georgia: economic, social, political, 1865-1872|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=i5shAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA156|year=1915|publisher=Columbia University Press|page=156}}</ref> |

On April 14, 1865, President Lincoln [[Assassination of Abraham Lincoln|was assassinated]] by [[John Wilkes Booth]]. With Congress out of session, Lincoln's successor [[Andrew Johnson]] began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new governments in seven Southern states (North Carolina, Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, Alabama, South Carolina, and Florida). Johnson established political conventions populated by delegates he had approved; he strongly encouraged these conventions to ratify the amendment (and also repeal their states' ordinances of secession).<ref>Harrison, "Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments" (2001), p. 394–397. "Then came the kicker: The President decided who was loyal, prescribing suffrage qualifications for electing the convention. [...] Pursuant to Johnson's proclamations, the provisional governors organized elections for conventions. Six met in 1865, while Texas's convention did not organize until March 1866. Three leading issues came before the convention: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt."</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Eric L. McKitrick|title=Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=MqL8lmT74HEC&pg=PA178|year=1960|publisher=U. Chicago Press|page=178|isbn=9780195057072}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Clara Mildred Thompson|title=Reconstruction in Georgia: economic, social, political, 1865-1872|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=i5shAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA156|year=1915|publisher=Columbia University Press|page=156}}</ref> |

||

| Line 63: | Line 62: | ||

South Carolina, Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia ratified the amendment in November and December 1865—bringing the total to 27, three-quarters of the 36 states that existed before the war. On December 18, 1865, Seward proclaimed the amendment to have been adopted as of December 6 (the date of Georgia's ratification), acknowledging thereby that all 36 states were considered valid members of the Union.<ref name="Harper" /><ref>Harrison, "Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments" (2001), p. 398. "[Seward] counted thirty-six states in all, thus rejecting the possibility that any had left the Union or been destroyed. With Georgia's action on December 6, he counted twenty-seven ratifications. So on December 18, 1865, in keeping with a duty imposed on the Secretary of State by a statute from 1818, he issued a certificate stating that Congress had proposed a constitutional amendment by the requisite two-thirds vote, that twenty-seven states had ratified, that the whole number of states in the Union was thirty-six, that twenty-seven was the requisite three-fourths majority, and that the amendment had 'be[come] valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution of the United States."</ref> Thomas Corwin died the same day.<ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), p. 233.</ref> |

South Carolina, Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia ratified the amendment in November and December 1865—bringing the total to 27, three-quarters of the 36 states that existed before the war. On December 18, 1865, Seward proclaimed the amendment to have been adopted as of December 6 (the date of Georgia's ratification), acknowledging thereby that all 36 states were considered valid members of the Union.<ref name="Harper" /><ref>Harrison, "Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments" (2001), p. 398. "[Seward] counted thirty-six states in all, thus rejecting the possibility that any had left the Union or been destroyed. With Georgia's action on December 6, he counted twenty-seven ratifications. So on December 18, 1865, in keeping with a duty imposed on the Secretary of State by a statute from 1818, he issued a certificate stating that Congress had proposed a constitutional amendment by the requisite two-thirds vote, that twenty-seven states had ratified, that the whole number of states in the Union was thirty-six, that twenty-seven was the requisite three-fourths majority, and that the amendment had 'be[come] valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution of the United States."</ref> Thomas Corwin died the same day.<ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), p. 233.</ref> |

||

Florida ratified the Amendment on December 28, 1865;<ref name="Harper">{{cite web|url=http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/HubPages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05Results|publisher=''Harper Weekly''|accessdate=February 18, 2013|title=The 13th Amendment: Ratification and Results}}</ref> New Jersey in 1866;<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentMediaite">{{cite web|url=http://www.mediaite.com/online/mississippi-officially-ratifies-13th-amendment-banning-slavery-148-years-later/ |title=Mississippi Officially Ratifies 13th Amendment Banning Slavery… 148 Years Later |author=Andrew Kirell |publisher=Mediaite |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013}}</ref> Texas in 1870;<ref name="Harper"/> Delaware in 1901;<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentLosAngelesTimes">{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2013/feb/18/nation/la-na-nn-mississippi-ratifies-slavery-amendment-20130218 |title=148 years later, Mississippi ratifies amendment banning slavery |author=Matt Pearce |publisher=Los Angeles Times |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013}}</ref> and Kentucky in 1976.<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentLosAngelesTimes"/> Mississippi, whose legislature voted in 1995 to ratify, belatedly notified the [[Office of the Federal Register]] in February 2013 of that legislative action, completing the legal process for the state.<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentABCNews">{{cite web|url=http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/headlines/2013/02/mississippi-officially-abolishes-slavery-ratifies-13th-amendment/ |title=Mississippi Officially Abolishes Slavery, Ratifies 13th Amendment |author=Ben Waldron |publisher=ABC News |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013|archivedate=June 4, 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6H7vSJlxX|deadurl=no}}</ref> |

Florida ratified the Amendment on December 28, 1865;<ref name="Harper">{{cite web|url=http://13thamendment.harpweek.com/HubPages/CommentaryPage.asp?Commentary=05Results|publisher=''Harper Weekly''|accessdate=February 18, 2013|title=The 13th Amendment: Ratification and Results}}</ref> New Jersey in 1866;<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentMediaite">{{cite web|url=http://www.mediaite.com/online/mississippi-officially-ratifies-13th-amendment-banning-slavery-148-years-later/ |title=Mississippi Officially Ratifies 13th Amendment Banning Slavery… 148 Years Later |author=Andrew Kirell |publisher=Mediaite |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013}}</ref> Texas in 1870;<ref name="Harper" /> Delaware in 1901;<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentLosAngelesTimes">{{cite web|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2013/feb/18/nation/la-na-nn-mississippi-ratifies-slavery-amendment-20130218 |title=148 years later, Mississippi ratifies amendment banning slavery |author=Matt Pearce |publisher=Los Angeles Times |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013}}</ref> and Kentucky in 1976.<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentLosAngelesTimes" /> Mississippi, whose legislature voted in 1995 to ratify, belatedly notified the [[Office of the Federal Register]] in February 2013 of that legislative action, completing the legal process for the state.<ref name="Mississippi13thAmendmentABCNews">{{cite web|url=http://abcnews.go.com/blogs/headlines/2013/02/mississippi-officially-abolishes-slavery-ratifies-13th-amendment/ |title=Mississippi Officially Abolishes Slavery, Ratifies 13th Amendment |author=Ben Waldron |publisher=ABC News |date=February 18, 2013 |accessdate=April 23, 2013|archivedate=June 4, 2013|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6H7vSJlxX|deadurl=no}}</ref> |

||

The ratification dates by state are as follows: |

The ratification dates by state are as follows: |

||

| Line 92: | Line 91: | ||

# Alabama (December 2, 1865) |

# Alabama (December 2, 1865) |

||

# North Carolina (December 4, 1865) |

# North Carolina (December 4, 1865) |

||

# Georgia (December 6, 1865)<ref name=AAR>{{cite web |url=http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/united-states-ratifies-13th-amendment-constitution |title=The United States Ratifies the 13th Amendment to the Constitution |publisher=African-American Registry |accessdate=June 11, 2013 |archivedate=June 11, 2013 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6HIQ5YF6f |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

# Georgia (December 6, 1865)<ref name="AAR">{{cite web |url=http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/united-states-ratifies-13th-amendment-constitution |title=The United States Ratifies the 13th Amendment to the Constitution |publisher=African-American Registry |accessdate=June 11, 2013 |archivedate=June 11, 2013 |archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6HIQ5YF6f |deadurl=no}}</ref> |

||

The following states ratified the amendment after its enactment: |

The following states ratified the amendment after its enactment: |

||

| Line 103: | Line 102: | ||

# Delaware (February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on February 8, 1865) |

# Delaware (February 12, 1901, after having rejected it on February 8, 1865) |

||

# Kentucky (March 18, 1976, after having rejected it on February 24, 1865) |

# Kentucky (March 18, 1976, after having rejected it on February 24, 1865) |

||

# Mississippi (March 16, 1995, after having rejected it on December 5, 1865)<ref name=AAR /> |

# Mississippi (March 16, 1995, after having rejected it on December 5, 1865)<ref name="AAR" /> |

||

==Effects== |

==Effects== |

||

[[File:13th Amendment Pg1of1 AC.jpg|190px|thumb|Amendment XIII in the [[National Archives and Records Administration|National Archives]], bearing the signature of Abraham Lincoln]] |

[[File:13th Amendment Pg1of1 AC.jpg|190px|thumb|Amendment XIII in the [[National Archives and Records Administration|National Archives]], bearing the signature of Abraham Lincoln]] |

||

The Thirteenth Amendment legally abolished chattel slavery in the United States and mooted parts of the original constitution which deal with slavery.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 17 & 34. "It rendered all clauses directly dealing with slavery null and altered the meaning of other clauses that had originally been designed to protect the institution of slavery."</ref><ref>[http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/13thamendment.html "The Thirteenth Amendment"], ''Primary Documents in American History'', Library of Congress. Retrieved Feb 15, 2007</ref> Although the majority of Kentucky's slaves had been emancipated, 65,000 people remained to be legally freed when the Amendment went into effect on December 18.<ref>Lowell Harrison & James C. Klotter, ''A New History of Kentucky'', University Press of Kentucky, 1997; p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=FdTIIEZ1k2QC&pg=PA180 180]; ISBN 9780813126210</ref> Slaves in Delaware also became legally free.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |year=2011 |title = |

The Thirteenth Amendment legally abolished chattel slavery in the United States and mooted parts of the original constitution which deal with slavery.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 17 & 34. "It rendered all clauses directly dealing with slavery null and altered the meaning of other clauses that had originally been designed to protect the institution of slavery."</ref><ref>[http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/13thamendment.html "The Thirteenth Amendment"], ''Primary Documents in American History'', Library of Congress. Retrieved Feb 15, 2007</ref> Although the majority of Kentucky's slaves had been emancipated, 65,000 people remained to be legally freed when the Amendment went into effect on December 18.<ref>Lowell Harrison & James C. Klotter, ''A New History of Kentucky'', University Press of Kentucky, 1997; p. [http://books.google.ca/books?id=FdTIIEZ1k2QC&pg=PA180 180]; ISBN 9780813126210</ref> Slaves in Delaware also became legally free.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |year=2011 |title =Delaware|encyclopedia=Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia |publisher=ABC-CLIO |editor-first=Alan |editor-last=Hornsby |page=139 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fB3rQefP8wQC&pg=PA139&lpg=PA139&dq=%22thirteenth+amendment%22+Delaware+hundred&source=bl&ots=mz-bBgXQI3&sig=kP4IKzKaMmtAFBsqoRA9FRhwdWY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=dcm9UZLOFeXe0QG-w4GoDg&ved=0CHMQ6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=%22thirteenth%20amendment%22%20Delaware%20hundred&f=false}}</ref> |

||

As the amendment still permitted labor as punishment for convicted criminals, Southern states responded with what [[Douglas A. Blackmon]] called "an array of interlocking laws essentially intended to criminalize black life".{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}} [[Black Codes (United States)|Black Codes]] were passed restricting the rights of black Americans;<ref name=Stromberg111 /> in 1865, for example, a Mississippi ordinance required black workers to contract with white farmers by January 1 of each year.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}} Mississippi also rescinded Blacks' [[Second Amendment to the United States Constitution|Second Amendment]] right to "keep and bear arms".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 52. "The Mississippi code denied to civilian blacks equal coverage under the Second Amendment, prohibiting them from owning Bowie knives, firearms, or ammunition."</ref> Blacks could be sentenced to forced labor for crimes including petty theft, using obscene language, or selling cotton after sunset.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=100}} States passed new, strict [[Vagrancy (people)|vagrancy]] laws that were selectively enforced against blacks without white protectors.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}}<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 51–52.</ref> The labor of these convicts was then sold to farms, factories, lumber camps, quarries, and mines.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=6}} Some states mandated indefinitely long periods of child "apprenticeship".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 50.</ref> Some laws did not target Blacks specifically, but instead affected farm workers—most of whom were Black. At the same time, many states passed laws to actively prevent Blacks from acquiring property.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 51.</ref> |

As the amendment still permitted labor as punishment for convicted criminals, Southern states responded with what [[Douglas A. Blackmon]] called "an array of interlocking laws essentially intended to criminalize black life".{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}} [[Black Codes (United States)|Black Codes]] were passed restricting the rights of black Americans;<ref name="Stromberg111" /> in 1865, for example, a Mississippi ordinance required black workers to contract with white farmers by January 1 of each year.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}} Mississippi also rescinded Blacks' [[Second Amendment to the United States Constitution|Second Amendment]] right to "keep and bear arms".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 52. "The Mississippi code denied to civilian blacks equal coverage under the Second Amendment, prohibiting them from owning Bowie knives, firearms, or ammunition."</ref> Blacks could be sentenced to forced labor for crimes including petty theft, using obscene language, or selling cotton after sunset.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=100}} States passed new, strict [[Vagrancy (people)|vagrancy]] laws that were selectively enforced against blacks without white protectors.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=53}}<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 51–52.</ref> The labor of these convicts was then sold to farms, factories, lumber camps, quarries, and mines.{{sfn|Blackmon|2008|p=6}} Some states mandated indefinitely long periods of child "apprenticeship".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 50.</ref> Some laws did not target Blacks specifically, but instead affected farm workers—most of whom were Black. At the same time, many states passed laws to actively prevent Blacks from acquiring property.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 51.</ref> |

||

Following the passage of Thirteenth Amendment by Congress, Republicans grew concerned over the increase it would create in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states; because the full population of freed slaves would be counted rather than three-fifths, the Southern states would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=22}}<ref name=Stromberg111>Stromberg, "A Plain Folk Perspective" (2002), p. 111.</ref> Republicans hoped to offset this advantage by attracting and protecting votes of the newly enfranchised black population.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=22}}<ref>{{cite book |title=The Fourteenth Amendment: From Political Principle to Judicial Doctrine |last=Nelson |first=William E. |year=1988 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=9780674041424 |page=47 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=VMCXjRyyKTQC&pg=PA46&dq=thirteenth+amendment+%22three+fifths%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Bz-xUemzGMX8rAGamYDgDQ&ved=0CEQQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=thirteenth%20amendment%20%22three%20fifths%22&f=false |accessdate=June 6, 2013}}</ref><ref>Stromberg, "A Plain Folk Perspective" (2002), p. 112.</ref> |

Following the passage of Thirteenth Amendment by Congress, Republicans grew concerned over the increase it would create in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states; because the full population of freed slaves would be counted rather than three-fifths, the Southern states would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=22}}<ref name="Stromberg111">Stromberg, "A Plain Folk Perspective" (2002), p. 111.</ref> Republicans hoped to offset this advantage by attracting and protecting votes of the newly enfranchised black population.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=22}}<ref>{{cite book |title=The Fourteenth Amendment: From Political Principle to Judicial Doctrine |last=Nelson |first=William E. |year=1988 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=9780674041424 |page=47 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=VMCXjRyyKTQC&pg=PA46&dq=thirteenth+amendment+%22three+fifths%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Bz-xUemzGMX8rAGamYDgDQ&ved=0CEQQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=thirteenth%20amendment%20%22three%20fifths%22&f=false |accessdate=June 6, 2013}}</ref><ref>Stromberg, "A Plain Folk Perspective" (2002), p. 112.</ref> |

||

Congress subsequently passed the [[Civil Rights Act of 1866]], which guaranteed citizenship and equal protection of the law to black Americans, though not guaranteeing the right to vote. The Amendment was also used as authorization for the [[Freedmen's Bureau bills|Freedmen's Bureau Act]]. President Andrew Johnson vetoed both bills, but was each time overridden by a two-thirds majority of Congress, and the bills passed into law.<ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), pp. 233–234.</ref><ref>[[W. E. B. DuBois]], "[http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/01mar/dubois2.htm The Freedmen's Bureau]", ''The Atlantic'', March 1901.</ref> |

Congress subsequently passed the [[Civil Rights Act of 1866]], which guaranteed citizenship and equal protection of the law to black Americans, though not guaranteeing the right to vote. The Amendment was also used as authorization for the [[Freedmen's Bureau bills|Freedmen's Bureau Act]]. President Andrew Johnson vetoed both bills, but was each time overridden by a two-thirds majority of Congress, and the bills passed into law.<ref>Vorenberg, ''Final Freedom'' (2001), pp. 233–234.</ref><ref>[[W. E. B. DuBois]], "[http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/01mar/dubois2.htm The Freedmen's Bureau]", ''The Atlantic'', March 1901.</ref> |

||

| Line 117: | Line 116: | ||

Proponents of the Act including Trumbull and Wilson argued that Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment (enforcement power) authorized the federal government to legislate civil rights for the States. Others disagreed, maintaining that inequality conditions were distinct from slavery.<ref>McAward, "McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), pp. 1788–1790.</ref> Seeking more substantial justification, and fearing that future opponents would again seek to overturn the legislation, Congress and the states added additional protections to the Constitution: the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]] (1868), which defined citizenship and mandated equal protection under the law, and the [[Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fifteenth Amendment]] (1870), which banned racial voting restrictions.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|pp=23–24}} |

Proponents of the Act including Trumbull and Wilson argued that Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment (enforcement power) authorized the federal government to legislate civil rights for the States. Others disagreed, maintaining that inequality conditions were distinct from slavery.<ref>McAward, "McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment" (2012), pp. 1788–1790.</ref> Seeking more substantial justification, and fearing that future opponents would again seek to overturn the legislation, Congress and the states added additional protections to the Constitution: the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]] (1868), which defined citizenship and mandated equal protection under the law, and the [[Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fifteenth Amendment]] (1870), which banned racial voting restrictions.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|pp=23–24}} |

||

The [[Freedmen's Bureau]] enforced the Amendment locally, providing a degree of support for people subject to the Black Codes.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 50–51. "Blacks applied to local provost marshalls and Freedmen's Bureau for help against these child abductions, particularly in those cases where children were taken from living parents. Jack Prince asked for help when a woman bound his maternal niece. Sally Hunter requested assistance to obtain the release of her two nieces. Bureau officials finally put an end to the system of indenture in 1867".</ref> The Civil Rights Act circumvented racism in local jurisdictions by allowing blacks access to the federal courts. The [[Enforcement Acts]] of 1870–1871 and the [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]], in combating the violence and intimidation of white supremacy, were also part of the effort to end slave conditions for Southern blacks.<ref name=Tsesis66>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 66–67.</ref> However, the effect of these laws waned as political will diminished and the federal government lost authority in the South—particularly after the [[Compromise of 1877]] ended [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]] in exchange for a Republican presidency.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 56–57, 60–61. "If the Republicans had hoped to gradually use section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment to pass Reconstruction legislation, they would soon learn that President Johnson, using his veto power, would make increasingly more difficult the passage of any measure augmenting the power of the national government. Further, with time, even leading antislavery Republicans would become less adamant and more willing to reconcile with the South than protect the rights of the newly freed. This was clear by the time Horace Greely accepted the Democratic nomination for president in 1872 and even more when President Rutherford B. Hayes entered the Compromise of 1877, agreeing to withdraw federal troops from the South." </ref> |

The [[Freedmen's Bureau]] enforced the Amendment locally, providing a degree of support for people subject to the Black Codes.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 50–51. "Blacks applied to local provost marshalls and Freedmen's Bureau for help against these child abductions, particularly in those cases where children were taken from living parents. Jack Prince asked for help when a woman bound his maternal niece. Sally Hunter requested assistance to obtain the release of her two nieces. Bureau officials finally put an end to the system of indenture in 1867".</ref> The Civil Rights Act circumvented racism in local jurisdictions by allowing blacks access to the federal courts. The [[Enforcement Acts]] of 1870–1871 and the [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]], in combating the violence and intimidation of white supremacy, were also part of the effort to end slave conditions for Southern blacks.<ref name="Tsesis66">Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 66–67.</ref> However, the effect of these laws waned as political will diminished and the federal government lost authority in the South—particularly after the [[Compromise of 1877]] ended [[Reconstruction Era|Reconstruction]] in exchange for a Republican presidency.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 56–57, 60–61. "If the Republicans had hoped to gradually use section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment to pass Reconstruction legislation, they would soon learn that President Johnson, using his veto power, would make increasingly more difficult the passage of any measure augmenting the power of the national government. Further, with time, even leading antislavery Republicans would become less adamant and more willing to reconcile with the South than protect the rights of the newly freed. This was clear by the time Horace Greely accepted the Democratic nomination for president in 1872 and even more when President Rutherford B. Hayes entered the Compromise of 1877, agreeing to withdraw federal troops from the South." </ref> |

||

==Interpretation== |

==Interpretation== |

||

| Line 124: | Line 123: | ||

In ''[[s:Blyew v. United States|Blyew v. U.S.]]'', (1872)<ref>80 U.S. 581 (1871)</ref> the Supreme Court heard another Civil Rights Act case relating to federal courts in Kentucky. John Bylew and George Kennard were white men visiting the cabin of a black family, the Fosters. Bylew apparently became angry with sixteen year old Richard Foster and hit him twice in the head with an ax. Bylew and Kennard killed Richard's parents, Sallie and Jack Foster, and his blind grandmother, Lucy Armstrong. They severely wounded the Fosters' two young daughters. Kentucky courts would not allow the Foster children to testify against Blyew and Kennard. But federal courts, authorized by the Civil Rights Act, found Blyew and Kennard guilty of murder. When the Supreme Court took the case, they ruled (5–2) that the Foster children did not have standing in federal courts because only living people could take advantage of the Act. In doing so, the Courts effectively ruled that Thirteenth Amendment did not permit a federal remedy in murder cases. Swayne and [[Joseph P. Bradley]] dissented, maintaining that in order to have meaningful effects, the Thirteenth Amendment would have to address systemic racial oppression.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 64–66.</ref> |

In ''[[s:Blyew v. United States|Blyew v. U.S.]]'', (1872)<ref>80 U.S. 581 (1871)</ref> the Supreme Court heard another Civil Rights Act case relating to federal courts in Kentucky. John Bylew and George Kennard were white men visiting the cabin of a black family, the Fosters. Bylew apparently became angry with sixteen year old Richard Foster and hit him twice in the head with an ax. Bylew and Kennard killed Richard's parents, Sallie and Jack Foster, and his blind grandmother, Lucy Armstrong. They severely wounded the Fosters' two young daughters. Kentucky courts would not allow the Foster children to testify against Blyew and Kennard. But federal courts, authorized by the Civil Rights Act, found Blyew and Kennard guilty of murder. When the Supreme Court took the case, they ruled (5–2) that the Foster children did not have standing in federal courts because only living people could take advantage of the Act. In doing so, the Courts effectively ruled that Thirteenth Amendment did not permit a federal remedy in murder cases. Swayne and [[Joseph P. Bradley]] dissented, maintaining that in order to have meaningful effects, the Thirteenth Amendment would have to address systemic racial oppression.<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), pp. 64–66.</ref> |

||

Though based on a technicality, the ''Blyew'' case set a precedent in state and federal courts that led to the erosion of Congress's Thirteenth Amendment powers. The Supreme Court continued along this path in the ''[[Slaughter-House Cases]]'' (1873), which upheld a state-sanctioned monopoly of white butchers. In ''[[United States v. Cruikshank|U.S. v. Cruikshank]]'' (1876), the Court ignored Thirteenth Amendment dicta from Circuit Court decision (by Joseph Bradley) to exonerate perpetrators of the [[Colfax massacre]] and invalidate the [[Enforcement Act of 1870]].<ref name=Tsesis66 /> |

Though based on a technicality, the ''Blyew'' case set a precedent in state and federal courts that led to the erosion of Congress's Thirteenth Amendment powers. The Supreme Court continued along this path in the ''[[Slaughter-House Cases]]'' (1873), which upheld a state-sanctioned monopoly of white butchers. In ''[[United States v. Cruikshank|U.S. v. Cruikshank]]'' (1876), the Court ignored Thirteenth Amendment dicta from Circuit Court decision (by Joseph Bradley) to exonerate perpetrators of the [[Colfax massacre]] and invalidate the [[Enforcement Act of 1870]].<ref name="Tsesis66" /> |

||

In ''[[Civil Rights Cases]]'',<ref>''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883)</ref> (1883), the Supreme Court reviewed five consolidated cases dealing with the [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]], which outlawed racial discrimination at "inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement". The Court ruled (8–1) that the Thirteenth Amendment did not ban most forms of racial discrimination by non-government actors.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=122}} In the majority decision, Bradley wrote (again in non-binding dicta) that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress to attack "badges and incidents of slavery". However, he distinguished between "fundamental rights" of citizenship, protected by the Thirteenth Amendment, and the "social rights of men and races in the community".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 70.</ref> The majority opinion held that ""it would be running the slavery argument into the ground to make it apply to every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car; or admit to his concert or theatre, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business."<ref>{{cite book|title=Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year ...|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YZ5RAAAAYAAJ|accessdate=11 June 2013|year=1888|publisher=D. Appleton & Company|p=132}}</ref> In his solitary dissent, [[John Marshall Harlan]] (a Kentucky lawyer who changed his mind about civil rights law after witnessing organized racist violence) argued that "such discrimination practiced by corporations and individuals in the exercise of their public or quasi-public functions is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power."<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 73.</ref> |

In ''[[Civil Rights Cases]]'',<ref>''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883)</ref> (1883), the Supreme Court reviewed five consolidated cases dealing with the [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]], which outlawed racial discrimination at "inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement". The Court ruled (8–1) that the Thirteenth Amendment did not ban most forms of racial discrimination by non-government actors.{{sfn|Goldstone|2011|p=122}} In the majority decision, Bradley wrote (again in non-binding dicta) that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress to attack "badges and incidents of slavery". However, he distinguished between "fundamental rights" of citizenship, protected by the Thirteenth Amendment, and the "social rights of men and races in the community".<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 70.</ref> The majority opinion held that ""it would be running the slavery argument into the ground to make it apply to every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car; or admit to his concert or theatre, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business."<ref>{{cite book|title=Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year ...|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YZ5RAAAAYAAJ|accessdate=11 June 2013|year=1888|publisher=D. Appleton & Company|p=132}}</ref> In his solitary dissent, [[John Marshall Harlan]] (a Kentucky lawyer who changed his mind about civil rights law after witnessing organized racist violence) argued that "such discrimination practiced by corporations and individuals in the exercise of their public or quasi-public functions is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power."<ref>Tsesis, ''The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom'' (2004), p. 73.</ref> |

||

| Line 135: | Line 134: | ||

===Involuntary servitude=== |

===Involuntary servitude=== |

||

In ''[[Selective Draft Law Cases]]'',<ref>{{ussc|245|366|1918}}</ref> the Supreme Court ruled that the [[Conscription in the United States|military draft]] was not "involuntary servitude". In ''[[United States v. Kozminski]]'',<ref name=Koz>{{ussc|487|931|1988}}</ref> the Supreme Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not prohibit compulsion of servitude through psychological coercion.<ref>[http://www.gpoaccess.gov/constitution/html/amdt13.html "Thirteenth Amendment—Slavery and Involuntary Servitude"], GPO Access, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1557</ref><ref>Risa Goluboff (2001), "The 13th Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights," ''Duke Law Journal,'' Vol 50, no. 228, p. 1609</ref> ''Kozminski'' limited involuntary servitude to those situations in which "the master subjects the servant to (1) threatened or actual physical force, (2) threatened or actual state-imposed legal coercion, or (3) fraud or deceit where the servant is a minor or an immigrant or is mentally incompetent."<ref name=Koz /> |

In ''[[Selective Draft Law Cases]]'',<ref>{{ussc|245|366|1918}}</ref> the Supreme Court ruled that the [[Conscription in the United States|military draft]] was not "involuntary servitude". In ''[[United States v. Kozminski]]'',<ref name="Koz">{{ussc|487|931|1988}}</ref> the Supreme Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not prohibit compulsion of servitude through psychological coercion.<ref>[http://www.gpoaccess.gov/constitution/html/amdt13.html "Thirteenth Amendment—Slavery and Involuntary Servitude"], GPO Access, U.S. Government Printing Office, p. 1557</ref><ref>Risa Goluboff (2001), "The 13th Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights," ''Duke Law Journal,'' Vol 50, no. 228, p. 1609</ref> ''Kozminski'' limited involuntary servitude to those situations in which "the master subjects the servant to (1) threatened or actual physical force, (2) threatened or actual state-imposed legal coercion, or (3) fraud or deceit where the servant is a minor or an immigrant or is mentally incompetent."<ref name="Koz" /> |

||

[[United States courts of appeals|U.S. Courts of Appeals]], in ''[[Immediato v. Rye Neck School District]]'', ''Herndon v. Chapel Hill'', and ''Steirer v. Bethlehem School District'', have ruled that the use of [[community service]] as a high school graduation requirement did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Loupe|first=Diane|date=August 2000|title=Community Service: Mandatory or Voluntary? – Industry Overview|journal=School Administrator|page=8|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0JSD/is_7_57/ai_77204744/pg_8/}}</ref> |

[[United States courts of appeals|U.S. Courts of Appeals]], in ''[[Immediato v. Rye Neck School District]]'', ''Herndon v. Chapel Hill'', and ''Steirer v. Bethlehem School District'', have ruled that the use of [[community service]] as a high school graduation requirement did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Loupe|first=Diane|date=August 2000|title=Community Service: Mandatory or Voluntary? – Industry Overview|journal=School Administrator|page=8|url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0JSD/is_7_57/ai_77204744/pg_8/}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:39, 16 June 2013

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution outlaws slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House on January 31, 1865, and adopted on December 6, 1865. On December 18, Secretary of State William H. Seward proclaimed it to have been adopted. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted during and after the American Civil War.

Slavery had been tacitly protected in the original US Constitution through clauses such as the Three-Fifths Compromise, in which three-fifths of the slave population would be counted for congressional representation. Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, no amendment to the Constitution had been successfully ratified in more than sixty years. Though many slaves had been declared free by Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, their post-war status was uncertain. The Senate passed an Amendment to abolish slavery April 8, 1864; after one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865. The measure was swiftly ratified by all Union states save for Delaware, New Jersey, and Kentucky, and by a sufficient number of border and "reconstructed" Southern states to be adopted by the end of the year.

The amendment abolished chattel slavery throughout the United States, though Black Codes and selective enforcement of statutes such as vagrancy laws continued to subject some black Americans to involuntary labor, particularly in the South. The Thirteenth Amendment was rarely cited in later case law, and no offenses have been prosecuted under it since 1947.

Text

- Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

- Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[1]

Background

Slavery in the United States

Slavery existed in every colony. The United States Constitution of 1787 did not use the word "slavery" but included several provisions about unfree persons. The Three-Fifths Compromise (in Article I, Section 2) allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three fifths of all other Persons".[3] The Fugitive Slave Clause (Article IV, Section 2) "no person held to service or labour in one state" would be freed by escaping to another. Article I, Section 9 allowed Congress to pass legislation to outlaw the "Importation of Persons", but not before after 1807.[4] However, for purposes of the Fifth Amendment—which states that "No person shall... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood as property.[5] Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it became part of the legal basis for treating slaves as property with Dred Scott v. Sanford.[6] Slavery was supported in practice by a pervasive culture of white supremacy.[7]

Between 1777 and 1804, every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861.[8] An abolitionist movement headed by such figures as William Lloyd Garrison grew in strength in the North, calling for the end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating sectional tensions. In 1836, the US House of Representatives instituted a gag rule against abolitionist petitions and speeches, attempting to stifle John Quincy Adams and other abolitionist congressmen. The American Colonization Society, in contrast, called for the emigration and colonization of African American slaves, who were freed, to Africa; its views were endorsed by politicians such as Henry Clay, who feared that the abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war.[9] Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.[10]

As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property.[11] The 1820 Missouri Compromise provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the Senate's equality between the regions. In 1846, the Wilmot Proviso was introduced to a war appropriations bill to ban slavery in all territories acquired in the Mexican–American War; the Proviso repeatedly passed the House, but not the Senate.[11] The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the issue by admitting California as a free state, instituting a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, banning the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and allowing New Mexico and Utah self-determination on the slavery issue.[12]

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin;[13] fighting between pro-slave and abolitionist forces in Kansas, beginning in 1854;[14] the 1857 Dred Scott decision by the US Supreme Court, which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850;[15] abolitionist John Brown's 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry;[16] and the 1860 election of the anti-slavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the Confederate States of America and beginning the American Civil War.[17]

Earlier proposed amendments