User:PerfectSoundWhatever/sandbox/0

- This page is a mock-up of what a summary style version of Blue would look like, giving due weight to multiple aspects.

| Blue | |

|---|---|

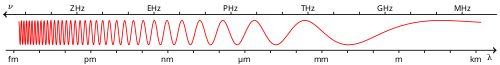

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | approx. 450–495 nm |

| Frequency | ~670–610 THz |

| Hex triplet | #0000FF |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (0, 0, 255) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (240°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (32, 131, 266°) |

| Source | HTML/CSS[1] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model.[2] It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The eye perceives blue when observing light with a dominant wavelength between approximately 450 and 495 nanometres. Most blues contain a slight mixture of other colours; azure contains some green, while ultramarine contains some violet. The clear daytime sky and the deep sea appear blue because of an optical effect known as Rayleigh scattering. An optical effect called Tyndall effect explains blue eyes. Distant objects appear more blue because of another optical effect called aerial perspective.

Surveys in the US and Europe show that blue is the colour most commonly associated with harmony, faithfulness, confidence, distance, infinity, the imagination, cold, and occasionally with sadness.[3] In US and European public opinion polls it is the most popular colour, chosen by almost half of both men and women as their favourite colour.[4] The same surveys also showed that blue was the colour most associated with the masculine, just ahead of black, and was also the colour most associated with intelligence, knowledge, calm, and concentration.[3]

Etymology and linguistics

The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe, from the Old French bleu, a word of Germanic origin, related to the Old High German word blao (meaning shimmering, lustrous).[5] In heraldry, the word azure is used for blue.[6]

In Russian, Spanish and some other languages, there is no single word for blue, but rather different words for light blue (голубой, goluboj; Celeste) and dark blue (синий, sinij; Azul). See Colour term.

Several languages, including Japanese, and Lakota Sioux, use the same word to describe blue and green. For example, in Vietnamese, the colour of both tree leaves and the sky is xanh. In Japanese, the word for blue (ao) is often used for colours that English speakers would refer to as green, such as the colour of a traffic signal meaning "go". In Lakota, the word tȟó is used for both blue and green, the two colours not being distinguished in older Lakota. (For more on this subject, see Distinguishing blue from green in language)

Linguistic research indicates that languages do not begin by having a word for the colour blue.[7] Colour names often developed individually in natural languages, typically beginning with black and white (or dark and light), and then adding red, and only much later – usually as the last main category of colour accepted in a language – adding the colour blue, probably when blue pigments could be manufactured reliably in the culture using that language.[7]

In science, optics, and nature

(lead / summary would go here)

In history, culture and art

The colour blue has been important in culture, politics, art and fashion since ancient times. Blue was used in ancient Egypt for jewellery and ornament. In the Renaissance, blue pigments were prized for paintings and fine blue and white porcelain. in the Middle Ages, deep rich blues made with cobalt were used in stained glass windows. In the 19th century, the colour was often used for military uniforms and fashion.

As the colour that most symbolized harmony, blue was chosen as the colour of the flags of the United Nations and the European Union.[8][page needed]

Surveys in the US and Europe show that blue is the colour most commonly associated with harmony, faithfulness, confidence, distance, infinity, the imagination, cold, and occasionally with sadness.[3] In US and European public opinion polls it is the most popular colour, chosen by almost half of both men and women as their favourite colour.[4] The same surveys also showed that blue was the colour most associated with the masculine, just ahead of black, and was also the colour most associated with intelligence, knowledge, calm, and concentration.[3]

Shades and variations

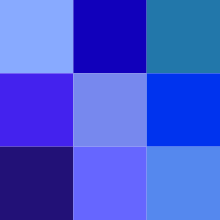

Varieties of the color blue may differ in hue, chroma (also called saturation, intensity, or colorfulness), or lightness (or value, tone, or brightness), or in two or three of these qualities. Variations in value are also called tints and shades, a tint being a blue or other hue mixed with white, a shade being mixed with black. A large selection of these colors is shown below.

As a structural colour

In nature, many blue phenomena arise from structural colouration, the result of interference between reflections from two or more surfaces of thin films, combined with refraction as light enters and exits such films. The geometry then determines that at certain angles, the light reflected from both surfaces interferes constructively, while at other angles, the light interferes destructively. Diverse colours therefore appear despite the absence of colourants.[9]

Colourants

Artificial blues

Egyptian blue, the first artificial pigment, was produced in the third millennium BC in Ancient Egypt. It is produced by heating pulverized sand, copper, and natron. It was used in tomb paintings and funereal objects to protect the dead in their afterlife. Prior to the 1700s, blue colourants for artwork were mainly based on lapis lazuli and the related mineral ultramarine. A breakthrough occurred in 1709 when German druggist and pigment maker Johann Jacob Diesbach discovered Prussian blue. The new blue arose from experiments involving heating dried blood with iron sulphides and was initially called Berliner Blau. By 1710 it was being used by the French painter Antoine Watteau, and later his successor Nicolas Lancret. It became immensely popular for the manufacture of wallpaper, and in the 19th century was widely used by French impressionist painters.[10] Beginning in the 1820s, Prussian blue was imported into Japan through the port of Nagasaki. It was called bero-ai, or Berlin blue, and it became popular because it did not fade like traditional Japanese blue pigment, ai-gami, made from the dayflower. Prussian blue was used by both Hokusai, in his wave paintings, and Hiroshige.[11]

In 1799 a French chemist, Louis Jacques Thénard, made a synthetic cobalt blue pigment which became immensely popular with painters.

In 1824 the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie in France offered a prize for the invention of an artificial ultramarine which could rival the natural colour made from lapis lazuli. The prize was won in 1826 by a chemist named Jean Baptiste Guimet, but he refused to reveal the formula of his colour. In 1828, another scientist, Christian Gmelin then a professor of chemistry in Tübingen, found the process and published his formula. This was the beginning of new industry to manufacture artificial ultramarine, which eventually almost completely replaced the natural product.[12]

In 1878 German chemists synthesized indigo. This product rapidly replaced natural indigo, wiping out vast farms growing indigo. It is now the blue of blue jeans. As the pace of organic chemistry accelerated, a succession of synthetic blue dyes were discovered including Indanthrone blue, which had even greater resistance to fading during washing or in the sun, and copper phthalocyanine.

-

The Blue Boy, featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[13]

-

The The Great Wave off Kanagawa illustrates the use of Prussian blue

-

A synthetic indigo dye factory in Germany in 1890.

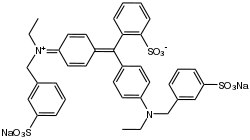

Dyes for textiles and food

Blue dyes are organic compounds, both synthetic and natural.[14] Woad and true indigo were once used but since the early 1900s, all indigo is synthetic. Produced on an industrial scale, indigo is the blue of blue jeans.

For food, the triarylmethane dye Brilliant blue FCF is used for candies. The search continues for stable, natural blue dyes suitable for the food industry.[14]

Pigments for painting and glass

Blue pigments were once produced from minerals, especially lapis lazuli and its close relative ultramarine. These minerals were crushed, ground into powder, and then mixed with a quick-drying binding agent, such as egg yolk (tempera painting); or with a slow-drying oil, such as linseed oil, for oil painting. Two inorganic but synthetic blue pigments are cerulean blue (primarily cobalt(II) stanate: Co

2SnO

4) and Prussian blue (milori blue: primarily Fe

7(CN)

18). The chromophore in blue glass and glazes is cobalt(II). Diverse cobalt(II) salts such as cobalt carbonate or cobalt(II) aluminate are mixed with the silica prior to firing. The cobalt occupies sites otherwise filled with silicon.

Inks

Methyl blue is the dominant blue pigment in inks used in pens.[15] Blueprinting involves the production of Prussian blue in situ.

Inorganic compounds

Certain metal ions characteristically form blue solutions or blue salts. Of some practical importance, cobalt is used to make the deep blue glazes and glasses. It substitutes for silicon or aluminum ions in these materials. Cobalt is the blue chromophore in stained glass windows, such as those in Gothic cathedrals and in Chinese porcelain beginning in the T'ang Dynasty. Copper(II) (Cu2+) also produces many blue compounds, including the commercial algicide copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4.5H2O). Similarly, vanadyl salts and solutions are often blue, e.g. vanadyl sulfate.

See also

References

- ^ "CSS Color Module Level 3". w3.org. Archived from the original on 2010-12-23.

- ^ Defonseka, Chris (20 May 2019). Polymeric Composites with Rice Hulls: An Introduction. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-064320-6.

- ^ a b c d Heller 2009, p. 24.

- ^ a b Heller 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Webster's Seventh New Collegiate Dictionary, (1970).

- ^ Friar, Stephen, ed. (1987). A New Dictionary of Heraldry. London: Alphabooks/A&C Black. pp. 40, 343. ISBN 978-0-906670-44-6.

- ^ a b "Why Isn't the Sky Blue?". Radiolab at WNYC Studios (Podcast). Producer: Tim Howard; Linguist: Guy Deutscher; Professor: Jules Davidoff. New York. 20 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

{{cite podcast}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Pastoureau 2000.

- ^ "Iridescence in Lepidoptera". Natural Photonics (originally in Physics Review Magazine). University of Exeter. September 1998. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ Michel Pastoureau, Bleu – HIstoire d'une couleur, pp. 114–16

- ^ Roger Keyes, Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, R, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 42, plate #140, p. 91 and catalogue entry #439, p. 185. for more on the story of Prussian blue in Japanese prints, see also the website of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

- ^ Maerz and Paul (1930). A Dictionary of Color New York: McGraw Hill p. 206

- ^ "Eight blue moments in art history". The Tate. Archived from the original on 2018-10-16. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ a b Newsome, Andrew G.; Culver, Catherine A.; Van Breemen, Richard B. (2014). "Nature's Palette: The Search for Natural Blue Colorants". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 62 (28): 6498–6511. doi:10.1021/jf501419q. PMID 24930897.

- ^ Placke, Mina; Fischer, Norbert; Colditz, Michael; Kunkel, Ernst; Bohne, Karl-Heinz (2016). "Drawing and Writing Materials". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_037.pub2. ISBN 9783527306732.

Works cited

- Ball, Philip (2001). Bright Earth, Art, and the Invention of Colour. London: Penguin Group. p. 507. ISBN 978-2-7541-0503-3. (page numbers refer to the French translation)

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques (in French). Munich: Pyramyd. ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Pastoureau, Michel (2000). Bleu: Histoire d'une couleur (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-086991-1.

- Varichon, Anne (2005). Couleurs : pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples (in French). Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-084697-4.

Further reading

- Balfour-Paul, Jenny (1998). Indigo. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-1776-8.

- Josserand, M.; Meeussen, E.; Majid, A. (27 September 2021). "Environment and culture shape both the colour lexicon and the genetics of colour perception". Sci Rep. 11 (19095). Nature. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Macdonald, Fiona (7 April 2018). "There's Evidence Humans Didn't Actually See Blue Until Modern Times". Science Alert. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- Mollo, John (1991). Uniforms of The American Revolution in Color. Illustrated by Malcolm McGregor. New York: Stirling Publications. ISBN 978-0-8069-8240-3.

External links

The dictionary definition of blue at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of blue at Wiktionary Media related to blue at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to blue at Wikimedia Commons- "Friday essay: from the Great Wave to Starry Night, how a blue pigment changed the world", By Dr Hugh Davies, theconversation.com

![Prussian blue, FeIII 4[FeII (CN) 6] 3, is the blue of blueprints.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Prussian_blue.jpg/684px-Prussian_blue.jpg)

![The Blue Boy, featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/The_Blue_Boy.jpg/203px-The_Blue_Boy.jpg)