Four Freedoms

The Four Freedoms were goals articulated by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Monday, January 6, 1941. In an address known as the Four Freedoms speech (technically the 1941 State of the Union address), he proposed four fundamental freedoms that people "everywhere in the world" ought to enjoy:

Roosevelt delivered his speech 11 months before the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which caused the United States to declare war on Japan on December 8, 1941. The State of the Union speech before Congress was largely about the national security of the United States and the threat to other democracies from world war. In the speech, he made a break with the long-held tradition of United States non-interventionism. He outlined the U.S. role in helping allies already engaged in warfare, especially Great Britain and China.

In that context, he summarized the values of democracy behind the bipartisan consensus on international involvement that existed at the time. A famous quote from the speech prefaces those values: "As men do not live by bread alone, they do not fight by armaments alone." In the second half of the speech, he lists the benefits of democracy, which include economic opportunity, employment, social security, and the promise of "adequate health care". The first two freedoms, of speech and religion, are protected by the First Amendment in the United States Constitution. His inclusion of the latter two freedoms went beyond the traditional Constitutional values protected by the U.S. Bill of Rights. Roosevelt endorsed a broader human right to economic security and anticipated what would become known decades later as the "human security" paradigm in studies of economic development. He also included the "freedom from fear" against national aggression and took it to the new United Nations he was setting up.

Historical context

[edit]In the 1930s many Americans, arguing that the involvement in World War I had been a mistake, were adamantly against continued intervention in European affairs.[1] With the Neutrality Acts established after 1935, U.S. law banned the sale of armaments to countries that were at war and placed restrictions on travel with belligerent vessels.[2]

When World War II began in September 1939, the neutrality laws were still in effect and ensured that no substantial support could be given to Britain and France. With the revision of the Neutrality Act in 1939, Roosevelt adopted a "methods-short-of-war policy" whereby supplies and armaments could be given to European Allies, provided no declaration of war could be made and no troops committed.[3] By December 1940, Europe was largely at the mercy of Adolf Hitler and Germany's Nazi regime. With Germany's defeat of France in June 1940, Britain and its overseas Empire stood alone against the military alliance of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Winston Churchill, as Prime Minister of Britain, called for Roosevelt and the United States to supply them with armaments in order to continue with the war effort.[citation needed]

The 1939 New York World's Fair had celebrated Four Freedoms – religion, speech, press, and assembly – and commissioned Leo Friedlander to create sculptures representing them. Mayor of New York City Fiorello La Guardia described the resulting statues as the "heart of the fair". Later Roosevelt would declare his own "Four Essential Freedoms" and call on Walter Russell to create a Four Freedoms Monument that was eventually dedicated at Madison Square Garden in New York City.[4]

They also appeared on the reverse of the AM-lira, the Allied Military Currency note issue that was issued in Italy during WWII, by the Americans, that was in effect occupation currency, guaranteed by the American dollar.

Declarations

[edit]The Four Freedoms Speech was given on January 6, 1941. Roosevelt's hope was to provide a rationale for why the United States should abandon the isolationist policies that emerged from World War I. In the address, Roosevelt critiqued Isolationism, saying: "No realistic American can expect from a dictator's peace international generosity, or return of true independence, or world disarmament, or freedom of expression, or freedom of religion–or even good business. Such a peace would bring no security for us or for our neighbors. 'Those, who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.'"[5]

The speech coincided with the introduction of the Lend-Lease Act, which promoted Roosevelt's plan to become the "arsenal of democracy"[6] and support the Allies (mainly the British) with much-needed supplies.[7] Furthermore, the speech established what would become the ideological basis for America's involvement in World War II, all framed in terms of individual rights and liberties that are the hallmark of American politics.[1]

The speech delivered by President Roosevelt incorporated the following text, known as the "Four Freedoms":[5]

In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech, and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want—which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear—which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium.

It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation.

That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.

— Franklin D. Roosevelt, excerpted from the State of the Union Address to the Congress, January 6, 1941[8]

Later in the same speech the president went on to specify six basic goals:[9]

- Equality of opportunity for youth and for others.

- Jobs for those who can work.

- Security for those who need it.

- The ending of special privilege for the few.

- The preservation of civil liberties for all.

- The enjoyment of the fruits of scientific progress in a wider and constantly rising standard of living.

Justification for war

[edit]The declaration of the Four Freedoms as a justification for war would resonate through the remainder of the war, and for decades longer as a frame of remembrance.[1] The Freedoms became the staple of America's war aims and the center of all attempts to rally public support for the war. With the creation of the Office of War Information (1942), as well as the famous paintings by Norman Rockwell, the Freedoms were advertised as values central to American life and examples of American exceptionalism.[10]

Opposition

[edit]The Four Freedoms Speech was popular, and the goals were influential in postwar politics. However, in 1941 the speech received heavy criticism from anti-war elements.[11] Critics argued that the Four Freedoms were simply a charter for Roosevelt's New Deal, social reforms that had already created sharp divisions within Congress. Conservatives who opposed social programs and increased government intervention argued against Roosevelt's attempt to justify and depict the war as necessary for the defense of lofty goals.[12]

While the Freedoms did become a forceful aspect of American thought on the war, they were never the exclusive justification for the war. Polls and surveys conducted by the United States Office of War Information (OWI) revealed that self-defense and vengeance for the attack on Pearl Harbor were still the most prevalent reasons for war.[13]

United Nations

[edit]The concept of the Four Freedoms became part of the personal mission undertaken by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1948. She helped inspire the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, General Assembly Resolution 217A. Indeed, these Four Freedoms were explicitly incorporated into the preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which reads: "Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy the freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed the highest aspiration of the common people."[14]

Disarmament

[edit]FDR called for "a world-wide reduction of armaments" as a goal for "the future days, which we seek to make secure" but one that was "attainable in our own time and generation." More immediately, though, he called for a massive build-up of U.S. arms production:

Every realist knows that the democratic way of life is at this moment being directly assailed in every part of the world ... The need of the moment is that our actions and our policy should be devoted primarily—almost exclusively—to meeting this foreign peril. ... [T]he immediate need is a swift and driving increase in our armament production. ... I also ask this Congress for authority and for funds sufficient to manufacture additional munitions and war supplies of many kinds, to be turned over to those nations which are now in actual war with aggressor nations.

— Franklin D. Roosevelt[15]

Violation

[edit]In a 1942 radio address, President Roosevelt declared the Four Freedoms embodied "rights of men of every creed and every race, wherever they live."[16] On February 19, 1942, he authorized Japanese American internment with Executive Order 9066. It allowed local military commanders to designate "military areas" as "exclusion zones", from which "any or all persons may be excluded". This power was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the entire Pacific coast, including all of California and much of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, except for those in internment camps.[17] By 1946, the United States had incarcerated 120,000 individuals of Japanese descent, of whom about 80,000 had been born in the United States.[18]

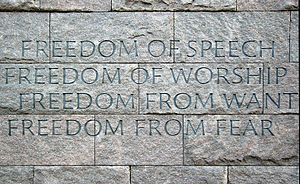

Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park

[edit]The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park is a park designed by the architect Louis Kahn for the south point of Roosevelt Island.[19] The park celebrates the famous speech, and text from the speech is inscribed on a granite wall in the final design of the park.

Awards

[edit]The Roosevelt Institute[20] honors outstanding individuals who have demonstrated a lifelong commitment to these ideals. The Four Freedoms Award medals are awarded at ceremonies at Hyde Park, New York and Middelburg, Netherlands during alternate years. The awards were first presented in 1982 on the centenary of President Roosevelt's birth as well as the bicentenary of diplomatic relations between the United States and the Netherlands.

Among the laureates have been:

- William Brennan

- H.M. Juan Carlos of Spain

- Jimmy Carter

- Bill Clinton

- The Dalai Lama

- Mikhail Gorbachev

- Averell Harriman

- Václav Havel

- H.R.H. Princess Juliana of the Netherlands

- John F. Kennedy

- Mike Mansfield

- Paul Newman

- Tip O'Neill

- Shimon Peres

- Coretta Scott King

- Brent Scowcroft

- Harry S. Truman

- Liv Ullmann

- Elie Wiesel

- Joanne Woodward

In popular culture

[edit]- John Crowley's novel Four Freedoms (2009) is largely based on the themes of Roosevelt's speech.

- FDR commissioned sculptor Walter Russell to design a monument to be dedicated to the first hero of the war. The Four Freedoms Monument was created in 1941 and dedicated at Madison Square Garden, in New York City, in 1943.

- Artist Kindred McLeary painted America the Mighty (1941), also known as Defense of Human Freedoms, in the State Department's Harry S. Truman Building.[21]

- Artist Hugo Ballin painted The Four Freedoms mural (1942) in the Council Chamber of the City Hall of Burbank, California.[22]

- New Jersey muralist Michael Lenson (1903–1972) painted The Four Freedoms mural (1943) for the Fourteenth Street School in Newark, New Jersey.[23]

- Muralist Anton Refregier painted the History of San Francisco murals (completed 1948) in the Rincon Center in San Francisco, California; panel 27 depicts the four freedoms.[24]

- Artist Mildred Nungester Wolfe painted a four-panel Four Freedoms mural (complete 1959) depicting the four freedoms for a country store in Richton, Mississippi. Those panels now hang in the Mississippi Museum of Art.[25]

- Allyn Cox painted four Four Freedoms murals (completed 1982) that hang in the Great Experiment Hall in the United States House of Representatives; each of the four panels depicts allegorical figures representing the four freedoms.[26]

- Since 1986, the fictional Four Freedoms Plaza has served as the headquarters for Marvel Comics superhero team Fantastic Four.[27]

- In the early 1990s, artist David McDonald reproduced Rockwell's Four Freedoms paintings as four large murals on the side of an old grocery building in downtown Silverton, Oregon.[28]

- In 2008, Florida International University's Wolfsonian museum hosted the Thoughts on Democracy exhibition that displayed posters created by 60 leading contemporary artists and designers, invited to create a new graphic design inspired by American illustrator Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms posters.[29]

- Four Freedoms is the adopted title of a bottom-shelf bourbon whiskey brand.[30]

Norman Rockwell's paintings

[edit]Roosevelt's speech inspired a set of four paintings by Norman Rockwell.

Paintings

[edit]The members of the set, known collectively as The Four Freedoms, were published in four consecutive issues of The Saturday Evening Post.[31] The four paintings subsequently were displayed around the US by the United States Department of the Treasury.

-

Freedom of Worship (Saturday, February 27, 1943) – from the Four Freedoms series by Norman Rockwell

-

Freedom from Want (Saturday, March 6, 1943) – from the Four Freedoms series by Norman Rockwell

-

Freedom from Fear (Saturday, March 13, 1943) – from the Four Freedoms series by Norman Rockwell

Essays

[edit]Each painting was published with a matching essay on that particular "Freedom":[32]

- Freedom of Speech, by Booth Tarkington (February 20, 1943).[33]

- Freedom of Worship, by Will Durant (February 27, 1943).[34]

- Freedom from Want, by Carlos Bulosan (March 6, 1943).[35]

- Freedom from Fear, by Stephen Vincent Benét (March 13, 1943; the date of Benét's death).[36]

Postage stamps

[edit]Rockwell's Four Freedoms paintings were reproduced as postage stamps by the United States Post Office in 1943,[37] in 1946,[38] and in 1994,[39] the centenary of Rockwell's birth.

See also

[edit]- Four boxes of liberty

- Four Freedoms (European Union)

- Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945, a Pulitzer-winning history of the era.

- Liberalism in the United States

- Second Bill of Rights, proposed by FDR in his 1944 State of the Union Address

- The Free Software Definition is often called "the four freedoms" within the free software community in reference to the speech and fundamental principles.

- World War II Victory Medal (United States), which includes the Four Freedoms on its reverse.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Bodnar, John, The "Good War" in American Memory (Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 11.

- ^ Kennedy, David M., Freedom From Fear: the American people in depression and war, 1929–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) 393–94.

- ^ Kennedy, David M., Freedom From Fear: the American people in depression and war, 1929–1945 (1999) 427–434.

- ^ Inazu, John D. (2012). Liberty's Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300173154.

- ^ a b "FDR, "The Four Freedoms," Speech Text |". Voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu. January 6, 1941. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt (New York: Random House and Harper and Brothers, 1940) 633–44.

- ^ , Kennedy, David M., Freedom From Fear: the American people in depression and war, 1929–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) 469.

- ^ See online copy from the University of California at Santa Barbara

- ^ Engel, p. 7.

- ^ Bodnar, John, The "Good War" in American Memory (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010) 12.

- ^ David M. Kennedy, Freedom From Fear: the American people in depression and war, 1929–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999) 470–76

- ^ John Bodnar, The "Good War" in American Memory (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010), 14–15.

- ^ Bodnar, The "Good War" in American Memory p. 14.

- ^ White, E.B.; Lerner, Max; Cowley, Malcolm; Niebuhr, Reinhold (1942). The United Nations Fight for the Four Freedoms. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. ASIN B003HKRK80.

- ^ Roosevelt, Franklin Delano (1941). – via Wikisource.

- ^ Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998) p. 223.

- ^ Korematsu v. the United States dissent by Justice Owen Josephus Roberts, reproduced at findlaw.com. Retrieved September 12, 2006.

- ^ Park, Yoosun, Facilitating Injustice: Tracing the Role of Social Workers in the World War II Internment of Japanese Americans. (Social Service Review 82.3, 2008) 448.

- ^ "About the Park". Four Freedoms Park Conservancy. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute

- ^ Vo, Tuan (October 2010). "Forgotten Treasure". State Magazine. pp. 20–23. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "City Council Chamber & Murals". Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "Official Website of Michael Lenson – WPA Muralist and Realist Painter". Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "War and Peace (1948)". SF Mural Arts. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ Lucas, Sherry (May 21, 2014). "Richton mural donated to Miss. Museum of Art". Hattiesburg American. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ "The American Story in Art: The Murals of Allyn Cox in the U.S. Capitol". The United States Capitol Historical Society. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ Stern, Roger (w), Buscema, John (p), Buscema, Sal (i), Oliver, Glynis (col), Workman, John (let), Daley, Don (ed). "The Best Man" Fantastic Four, vol. 1, no. 299, p. 10/1 (February 1987). New York, NY: Marvel Comics.

- ^ "Silverton Mural Society".

- ^ "Thoughts on Democracy". Wolfsonian FIU. 2008. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ "Four Freedoms Whiskey". GoToLiquorStore. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ On February 20, 1943; February 27, 1943; March 6, 1943; and March 13, 1943.

- ^ Perry, P. (2009a), "Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms", The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009; Perry, P. (2009b). "Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms", The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009.

- ^ "Booth Tarkington's 'Freedom of Speech', The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009". December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Will Durant's 'Freedom of Worship', The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009". December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Carlos Bulosan's 'Freedom from Want', The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009". December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Stephen Vincent Benét's 'Freedom from Fear', The Saturday Evening Post, January/February 2009". December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Scott Catalog souvenir sheet of four stamps".

- ^ "Scott Catalog souvenir sheet of four stamps".

- ^ "Scott Catalog souvenir sheet of four stamps". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved November 23, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Borgwardt, Elizabeth. "FDR's Four Freedoms as a Human Rights Instrument." OAH Magazine of History 22.2 (2008): 8–13. extract

- Crowell, Laura. "The building of the 'four freedoms' speech." Communications Monographs 22.5 (1955): 266–283.

- De Zayas, Alfred. "The Relevance of Roosevelt's Four Freedoms Today." 62 Nordic Journal of International Law 61 (1992): 239+.

- Dunn, Susan, A Blueprint for War: FDR and the Hundred Days That Mobilized America (2018) pp. 73–101.

- Engel, Jeffrey A., ed. The four freedoms: Franklin D. Roosevelt and the evolution of an American idea (Oxford University Press, 2015); argues that Roosevelt's speech left a deep imprint in America, but the society largely failed to achieve his vision of freedom, p. 7. online review

- Gutierrez, Robert. "The Four Freedoms Viewed in Comparison to Traditional American Political Ideals." Counterpoints, vol. 271, 2007, pp. 33–40. online

- Inazu, John D. "The Four Freedoms and the Future of Religious Liberty." North Carolina Law Review 92 (2013): 787+ online.

- Johnstone, Andrew. Against Immediate Evil: American Internationalists and the Four Freedoms on the Eve of World War II (Cornell University Press, 2015).

- Kaye, Harvey J. The fight for four freedoms: what made FDR and the greatest generation truly great (Simon and Schuster, 2014); 8 essays by scholars. online

- Posneer, Michael H. "The Four Freedoms Turn 70: Embracing an Integrated Approach to Human Rights." Proceedings of the Annual Meeting (American Society of International Law) vol. 105, 2011, pp. 27–31. online

- Rhodes, Jesse H. "The Evolution of Roosevelt's Rhetorical Legacy: Presidential Rhetoric about Rights in Domestic and Foreign Affairs, 1933–2011." Presidential Studies Quarterly 43.3 (2013): 562–591. online

- Shulman, Mark R. "The four freedoms: Good neighbors make good law and good policy in a time of insecurity." Fordham Law Review 77 (2008): 555–581 online.

- Wesley, Charles H., et al. "The Negro has Always Wanted The Four Freedoms." in What the Negro Wants, edited by Rayford W. Logan, (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001) pp. 90–112. online

Rockwell's icons

[edit]- Kimble, James J. "The illustrated four freedoms: FDR, Rockwell, and the margins of the rhetorical presidency." Presidential Studies Quarterly 45.1 (2015): 46–69.

- Lynch III, Sylvio. Morality and Aspiration: Some Conditions of Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms (PhD Diss. Bowling Green State University, 2020) online

- Murray, Stuart, James McCabe, and John Frohnmayer. Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms: Images that Inspire a Nation (Berkshire House, 1993) online.

- Olson, Lester G. "Portraits in praise of a people: A rhetorical analysis of Norman Rockwell's icons in Franklin D. Roosevelt's “four freedoms” campaign." Quarterly Journal of Speech 69.1 (1983): 15–24.

External links

[edit]- "Four Freedoms" Lesson plan for grades 9–12 from National Endowment for the Humanities

- As a delivered text, enhanced audio, video excerpt at AmericanRhetoric.com.

- Text and audio.

- "FDR4Freedoms Digital Resource" The digital education resource of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park

- "Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park"

- 1941 Four Freedoms Speech (via YouTube)

- Four Freedoms

- 1941 in politics

- 1941 in the United States

- 1941 in Washington, D.C.

- 1941 speeches

- 77th United States Congress

- History of human rights

- January 1941 events

- Politics of World War II

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Speeches by Franklin D. Roosevelt

- State of the Union addresses by Franklin D. Roosevelt

- World War II speeches

- January 1941 events in the United States

- 1940s State of the Union addresses