2012 VP113

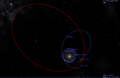

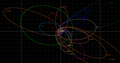

Orbit simulated with solar system, and position in 2017. (top and side views) | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Scott Sheppard Chad Trujillo Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (807) |

| Discovery date | 5 November 2012 announced: 26 March 2014 |

| Designations | |

| 2012 VP113 | |

| TNO, sednoid | |

| Orbital characteristics[2] | |

| Epoch 13 January 2016 (JD 2457400.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 5 | |

| Observation arc | 739 days (2.02 yr) |

| Earliest precovery date | 22 October 2011 |

| Aphelion | 438.11 AU (65.540 Tm) (Q) |

| Perihelion | 80.486 AU (12.0405 Tm) (q) |

| 265.8 AU (39.76 Tm) (a)[3] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.68960 (e) |

| 4175.54 yr (1525115 d) 4300 yr (barycentric)[4] | |

| 3.2115° (M) | |

| 0° 0m 0.85s /day (n) | |

| Inclination | 24.047° (i) |

| 90.818° (Ω) | |

| 293.72° (ω) | |

| Earth MOID | 79.5621 AU (11.90232 Tm) |

| Jupiter MOID | 75.862 AU (11.3488 Tm) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 300–1000 km[5] 450 km (assumed)[5][6] 600 km[7] |

| 0.15 (Nature; 2014)[6] 0.1 (Brown website)[7] | |

| (moderately red) V−R = 0.52 ± 0.04[6] B−V = 0.92 | |

| 23.4 | |

| 4.0 (MPC)[8] 4.0 (JPL)[2] 4.3[7] | |

2012 VP113 is a minor planet in the outer reaches of the Solar System. It was first observed on 5 November 2012[1] and announced on 26 March 2014.[6][9]

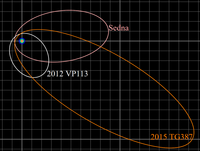

It is the object with the farthest known perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in the Solar System, greater than that of Sedna's.[10] Though its perihelion is farther, 2012 VP113 has an aphelion only about half that of Sedna's. It is the second discovered sednoid, with semi-major axis beyond 150 AU and perihelion greater than 50 AU. The similarity of the orbit of 2012 VP113 to other known extreme trans-Neptunian objects led Scott Sheppard and Chad Trujillo to suggest that an undiscovered super-Earth in the outer Solar System is shepherding these distant objects into similar type orbits.[6]

It has an absolute magnitude (H) of 4.0,[8] which makes it likely to be a dwarf planet,[7] and it is accepted as a dwarf planet by some.[11] It is expected to be about half the size of Sedna and similar in size to Huya.[5] Its surface is thought to have a pink tinge, resulting from chemical changes produced by the effect of radiation on frozen water, methane, and carbon dioxide.[12] This optical color is consistent with formation in the gas-giant region and not the classical Kuiper belt, which is dominated by ultra-red colored objects.[6]

History

Discovery

2012 VP113 was first observed on 5 November 2012[1] with NOAO's 4-meter Víctor M. Blanco Telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory.[13] Carnegie’s 6.5-meter Magellan telescope at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile was used to determine its orbit and surface properties.[13] Before being announced to the public, it was only tracked by Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (807) and Las Campanas Observatory (304).[8] It has an observation arc of about 2 years.[2] Two precovery measurements from 22 October 2011 have been reported.[8] A primary issue with observing it and finding precovery observations of it is that at an apparent magnitude of 23, it is too faint for most telescopes to easily observe.

Nickname

2012 VP113 was abbreviated "VP" and nicknamed "Biden" by the discovery team, after Joe Biden, who at the time of discovery, was Vice President (VP) of the United States.[9]

Orbit

2012 VP113 has the largest perihelion distance of any known object in the Solar System.[14] Its last perihelion was around 1979,[a] at a distance of 80 AU;[2] it is currently 84 AU from the Sun. Only nine other Solar System objects are known to have perihelia larger than 47 AU: Sedna (76 AU), 2014 FZ71 (56 AU), 2014 FC72 (52 AU), 2004 XR190 (51 AU), 2015 FJ345 (51 AU), 2013 SY99 (50 AU), 2010 GB174 (49 AU), 2014 SR349 (48 AU) and (474640) 2004 VN112 (47 AU).[14] The paucity of bodies with perihelia at 50–75 AU appears not to be an observational artifact.[6]

It is possibly a member of a hypothesized Hills cloud.[5][13][15] It has a perihelion, argument of perihelion, and current position in the sky similar to those of Sedna.[5] In fact, all known Solar System bodies with semi-major axes over 150 AU and perihelia greater than Neptune's have arguments of perihelion clustered near 340 ± 55°.[6] This could indicate a similar formation mechanism for these bodies.[6] (148209) 2000 CR105 was the first such object discovered.

It is currently unknown how 2012 VP113 acquired a perihelion distance beyond the Kuiper belt. The characteristics of its orbit, like those of Sedna's, have been explained as possibly created by a passing star or a trans-Neptunian planet of several Earth masses hundreds of astronomical units from the Sun.[16] The orbital architecture of the trans-Plutonian region may signal the presence of more than one planet.[17][18] 2012 VP113 could even be captured from another planetary system.[11] However, it is considered more likely that the perihelion of 2012 VP113 was raised by multiple interactions within the crowded confines of the open star cluster in which the Sun formed.[5]

-

Orbit simulated

-

2012 VP113 orbit in white with hypothetical Planet Nine

Sun

Jupiter trojans (6,178)

Scattered disc (>300) Giant planets: J · S · U · N

Centaurs (44,000)

Kuiper belt (>1,000)

(scale in AU; epoch as of January 2015; # of objects in parentheses)

These Solar System minor planets are the furthest from the Sun as of December 2021[update]. The objects have been categorized by their approximate current distance from the Sun, and not by the calculated aphelion of their orbit. The list changes over time because the objects are moving in their orbits. Some objects are inbound and some are outbound. It would be difficult to detect long-distance comets if it were not for their comas, which become visible when heated by the Sun. Distances are measured in astronomical units (AU, Sun–Earth distances). The distances are not the minimum (perihelion) or the maximum (aphelion) that may be achieved by these objects in the future.

This list does not include near-parabolic comets of which many are known to be currently more than 100 AU (15 billion km) from the Sun, but are currently too far away to be observed by telescope. Trans-Neptunian objects are typically announced publicly months or years after their discovery, so as to make sure the orbit is correct before announcing it. Due to their greater distance from the Sun and slow movement across the sky, trans-Neptunian objects with observation arcs less than several years often have poorly constrained orbits. Particularly distant objects take several years of observations to establish a crude orbit solution before being announced. For instance, the most distant known trans-Neptunian object 2018 AG37 was discovered by Scott Sheppard in January 2018 but was announced three years later in February 2021.[19]

Noted objects

One particularly distant body is 90377 Sedna, which was discovered in November 2003. It has an extremely eccentric orbit that takes it to an aphelion of 937 AU.[4] It takes over 10,000 years to orbit, and during the next 50 years it will slowly move closer to the Sun as it comes to perihelion at a distance of 76 AU from the Sun.[20] Sedna is the largest known sednoid, a class of objects that play an important role in the Planet Nine hypothesis.

Pluto (30–49 AU, about 34 AU in 2015) was the first Kuiper belt object to be discovered (1930) and is the largest known dwarf planet.

Gallery

- Notable trans-Neptunian objects

-

Orbit diagram of 2018 AG37, the furthest known Solar System object from the Sun as of 2022

-

Sedna viewed with Hubble Space Telescope, 2004

Known distant objects

This is a list of known objects at heliocentric distances of more than 65 AU. In theory, the Oort cloud could extend over 120,000 AU (2 ly) from the Sun.

| Object name | Distance from the Sun (AU) | Radial velocity (AU/yr)[b] |

Perihelion | Aphelion | Semimajor axis |

Apparent magnitude |

Absolute magnitude (H) |

Important dates | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| December 2021 | December 2015 | Discovered | Announced | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Great Comet of 1680 (for comparison) |

258.0[22] | 255.4[22] | +0.47[22] | 0.006 | 889 | 444 | Unknown | Unknown | 1680-11-14 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voyager 1 (for comparison) |

152.9[22] | 133.3[22] | +3.57[22] | 8.90 | ∞ Hyperbolic |

−3.2[23] | ~50 | ~28 | — | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 AG37 | 132.9±1.8 | 131.9±10.7 | ±0.2(?) | 27.1 | 145.0 | 86.0 | 25.4 | 4.2 | 2018-01-15 | 2021-02-10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Voyager 2 (for comparison) |

129.4[22] | 109.7[22] | +3.17[22] | 21.2 | ∞ Hyperbolic |

−4.0[23] | ~48 | ~28 | — | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pioneer 10 (for comparison) |

128.9[22] | 114.8[22] | +2.51[22] | 4.94 | ∞ Hyperbolic |

~49 | ~29 | — | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 VG18 | 123.6 | 123.2 | +0.06 | 37.8 | 123.9 | 81.3 | 24.6 | 3.7 | 2018-11-10 | 2018-12-17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 BE102 | 110.9 | 111.7 | 32.9 | 116.9 | 74.9 | 25.6 | 5.1 | 2020-01-24 | 2022-05-31 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pioneer 11 (for comparison) |

107.7[22] | 92.5[22] | +2.35[22] | 9.45 | ∞ Hyperbolic |

~48 | ~29 | — | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 FY30 | 98.9 | 99.9 | –0.17 | 35.6 | 107.7 | 71.6 | 24.8 | 4.7 | 2020-03-24 | 2021-02-14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 FA31 | 97.3 | 96.5 | +0.14 | 39.5 | 102.4 | 71.0 | 25.4 | 5.4 | 2020-03-24 | 2021-02-14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eris 136199 |

95.9 | 96.3 | −0.07 | 38.3 | 97.5 | 67.9 | 18.8 | −1.21 | 2003-10-21 | 2005-07-29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 FQ40 | 92.4 | 92.7 | –0.05 | 38.2 | 93.1 | 65.6 | 25.7 | 6.1 | 2020-03-24 | 2022-05-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 TH367[c] | 90.3 | 88.2 | +0.42 | 28.9 | 136.4 | 82.6 | 26.3 | 6.6 | 2015-10-13 | 2018-03-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 DR15 | 89.6 | 88.6 | +0.17(?) | 37.8 | 96.5 | 67.2 | 23.1 | 3.6 | 2021-02-17 | 2021-12-17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 UZ224 | 89.5 | 92.0 | −0.45 | 38.3 | 177.0 | 107.6 | 23.2 | 3.4 | 2014-10-21 | 2016-08-28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gonggong 225088 |

88.7 | 87.4 | +0.23 | 33.7 | 101.2 | 67.5 | 21.5 | 1.6 | 2007-07-17 | 2009-01-07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 FG415 | 87.2 | 87.9 | −0.14 | 36.2 | 92.1 | 64.1 | 25.5 | 6.0 | 2015-03-17 | 2019-03-27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 FC69 | 85.5 | 84.1 | +0.26 | 40.4 | 104.4 | 72.4 | 24.2 | 4.6 | 2014-03-25 | 2015-02-11 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2006 QH181 | 84.6 | 83.3 | +0.22 | 37.5 | 96.7 | 67.1 | 23.7 | 4.3 | 2006-08-21 | 2006-11-05 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sedna 90377 |

84.2 | 85.8 | −0.29 | 76.3 | 892.6 | 484.4 | 21.0 | 1.3 | 2003-11-14 | 2004-03-15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 VO166 | 84.3 | 82.5 | +0.32 | 38.3 | 113.2 | 75.8 | 25.5 | 5.9 | 2015-11-06 | 2018-10-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2012 VP113 | 84.2 | 83.3 | +0.16 | 80.4 | 442.6 | 261.5 | 23.5 | 4.0 | 2012-11-05 | 2014-03-26 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 FS28 | 83.5 | 85.9 | −0.62 | 34.2 | 358.2 | 196.2 | 24.3 | 4.9 | 2013-03-16 | 2016-08-29 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2017 SN132 | 82.8 | 80.4 | +0.44 | 42.0 | 110.0 | 76.0 | 25.2 | 5.8 | 2017-09-16 | 2019-02-10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 EU5 | 81.7 | 85.5 | 46.5 | 2310 | 1178 | 25.6 | 6.4 | 2019-03-05 | 2021-12-17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 UH87[c] | 81.3 | 82.3 | −0.19 | 34.3 | 90.0 | 62.2 | 25.2 | 6.0 | 2015-10-16 | 2018-03-12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 FY27 532037 |

79.7 | 80.3 | −0.10 | 35.2 | 82.1 | 58.7 | 22.2 | 3.2 | 2013-03-17 | 2014-03-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 DP15 | 79.7 | 76.2 | 29.1 | 204.1 | 116.6 | 25.4 | 6.2 | 2021-02-16 | 2021-12-17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 TJ367[c] | 79.4 | 77.1 | +0.42 | 33.6 | 128.1 | 80.9 | 25.8 | 6.7 | 2015-10-13 | 2018-03-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2017 FO161 | 78.1 | 79.1 | −0.18 | 34.1 | 85.5 | 59.8 | 23.3 | 4.3 | 2017-03-23 | 2018-04-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leleākūhonua 541132 |

77.6 | 79.8 | −0.40 | 65.2 | 2,106 | 1,085 | 24.6 | 5.5 | 2015-10-13 | 2018-10-01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 AD39 | 77.2 | 74.1 | –0.58 | 38.4 | 287.9 | 163.2 | 25.0 | 6.2 | 2018-01-15 | 2021-02-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 FB31 | 75.8 | 76.8 | –0.19 | 34.4 | 83.3 | 59.1 | 24.5 | 5.6 | 2020-03-24 | 2021-02-14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 AK39 | 75.3 | 75.4 | –0.01 | 27.3 | 75.4 | 51.4 | 25.3 | 6.5 | 2018-01-18 | 2021-02-18 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 LL37 | 73.9 | 74.2 | –0.05 | 36.1 | 74.6 | 55.4 | 22.7 | 4.0 | 2021-06-02 | 2022-05-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2010 GB174 | 73.6 | 70.7 | +0.54 | 48.7 | 630.7 | 339.7 | 25.3 | 6.5 | 2010-04-12 | 2013-04-30 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 VJ168 | 73.4 | 72.4 | +0.19 | 37.6 | 81.5 | 59.5 | 24.8 | 5.8 | 2015-11-06 | 2018-10-03 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 DU249 | 73.1 | 72.7 | +0.06 | 34.7 | 73.7 | 54.2 | 23.9 | 5.2 | 2015-02-17 | 2018-07-23 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 FJ72 | 72.6 | 70.1 | +0.46 | 38.4 | 148.2 | 93.3 | 24.4 | 5.6 | 2014-03-24 | 2016-08-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 TS97[c] | 71.2 | 71.5 | −0.04 | 36.2 | 71.7 | 54.0 | 24.9 | 6.1 | 2016-10-06 | 2018-04-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 GN55 | 71.0 | 72.1 | −0.19 | 32.5 | 78.4 | 55.5 | 24.6 | 5.8 | 2015-04-13 | 2018-09-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 VL168 | 69.7 | 72.1 | –0.44 | 37.7 | 136.0 | 86.8 | 24.7 | 6.1 | 2015-11-07 | 2018-10-03 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 BA95 | 69.6 | 68.4 | +0.20 | 35.9 | 76.5 | 56.2 | 24.3 | 5.8 | 2020-01-25 | 2021-12-17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 RZ277 | 69.3 | 67.5 | +0.32 | 34.7 | 90.5 | 62.6 | 25.6 | 6.8 | 2015-09-08 | 2018-10-01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 DJ17 | 69.0 | 69.2 | 40.4 | 69.4 | 54.9 | 23.2 | 6.7 | 2021-02-17 | 2022-05-31 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2012 FH84 | 68.8 | 68.4 | +0.07 | 41.9 | 70.1 | 56.0 | 25.8 | 7.2 | 2012-03-25 | 2016-06-07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 AC77 | 68.7 | 69.9 | –0.21 | 35.0 | 79.0 | 57.0 | 25.0 | 6.6 | 2019-01-11 | 2021-02-14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 GR50 | 68.6 | 68.2 | +0.07 | 38.2 | 69.7 | 54.0 | 25.2 | 6.6 | 2015-04-13 | 2016-08-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 FQ28 | 68.4 | 67.3 | +0.19 | 45.6 | 80.0 | 62.7 | 24.5 | 6.0 | 2013-03-17 | 2016-06-07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2011 GM89 | 68.3 | 68.5 | –0.24 | 36.5 | 68.8 | 52.7 | 25.7 | 7.1 | 2011-04-04 | 2016-08-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 DQ15 | 68.3 | 71.4 | 27.8 | 130.9 | 79.3 | 24.7 | 6.3 | 2021-02-16 | 2021-12-17 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 DG17 | 67.6 | 66.7 | +0.15 | 47.5 | 75.8 | 61.7 | 23.2 | 5.0 | 2021-02-17 | 2022-05-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 GP50 | 67.5 | 68.1 | –0.10 | 40.4 | 70.0 | 55.2 | 25.0 | 6.5 | 2015-04-14 | 2016-06-07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 CD289 | 67.2 | 66.2 | +0.18 | 37.5 | 74.0 | 55.8 | 25.7 | 7.3 | 2016-02-05 | 2018-03-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 VJ137 | 67.2 | 69.7 | –0.42 | 37.8 | 139.3 | 88.5 | 25.2 | 6.9 | 2018-01-15 | 2021-02-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 KV11 | 67.1 | 64.1 | +0.50 | 35.0 | 155.0 | 95.6 | 25.6 | 7.3 | 2020-05-29 | 2022-11-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 UD228 | 66.7 | 65.7 | +0.18 | 36.7 | 73.3 | 55.0 | 24.5 | 6.1 | 2014-10-22 | 2017-12-07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 GB277 | 66.2 | 68.3 | –0.39 | 40.0 | 119.4 | 79.7 | 25.6 | 7.3 | 2016-04-10 | 2020-06-04 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 GZ276 | 66.1 | 69.2 | –0.56 | 38.6 | 253.6 | 146.1 | 25.3 | 7.0 | 2016-04-10 | 2020-06-03 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 FL72 | 66.1 | 63.3 | +0.47 | 38.0 | 167.1 | 102.5 | 25.1 | 6.8 | 2014-03-26 | 2016-08-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 TQ120[c] | 65.8 | 63.7 | +0.37 | 42.3 | 114.3 | 78.3 | 25.0 | 6.7 | 2016-10-06 | 2020-06-04 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 RQ281 | 65.7 | 62.7 | +0.56 | 36.9 | 210.6 | 123.8 | 25.1 | 6.8 | 2015-09-05 | 2019-03-27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 BS60[c] | 65.7 | 68.0 | –0.42 | 31.0 | 104.1 | 67.6 | 24.6 | 6.5 | 2020-01-26 | 2021-02-23 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 UJ15 | 65.4 | 64.8 | +0.11 | 37.2 | 67.4 | 52.3 | 25.4 | 7.0 | 2013-10-28 | 2016-08-31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 EV5 | 65.3 | 63.5 | +0.30 | 32.0 | 79.8 | 55.9 | 25.8 | 7.6 | 2020-03-05 | 2021-12-17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 FD70 | 65.2 | 63.8 | +0.26 | 35.9 | 78.6 | 57.3 | 25.1 | 6.9 | 2014-03-25 | 2018-04-02 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 AZ18 | 65.1 | 65.9 | –0.15 | 39.1 | 70.5 | 54.8 | 26.0 | 7.7 | 2018-01-15 | 2019-03-27 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 KV167 | 65.0 | 65.2 | –0.03 | 38.0 | 65.3 | 51.6 | 25.6 | 7.2 | 2015-05-18 | 2018-03-13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018 VO35 | 65.0 | 67.8 | –0.51 | 35.2 | 152.2 | 93.7 | 24.9 | 6.8 | 2018-11-10 | 2019-02-10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2020 KX11[c] | 65.0 | 65.0 | –0.01 | 64.6 | 67.1 | 65.9 | 26.4 | 8.2 | 2020-05-29 | 2020-09-25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This table includes all observable objects currently located at least 65 AU from the Sun.[21] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Comparison

See also

- List of Solar System objects most distant from the Sun in 2015

- V774104

- 90377 Sedna (relatively large and also distant body)

- List of hyperbolic comets

- Pluto

- Have very large aphelion

Notes

- ^ The 1-sigma uncertainty in the year of perihelion passage is ~4 years using JPL solution 2.[2]

- ^ AU/yr indicates whether the object is moving inwards or outwards in its orbit, and the rate at which it does so.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cite error: The named reference

shortarcwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

References

- ^ a b c "MPEC 2014-F40 : 2012 VP113". IAU Minor Planet Center. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014. (K12VB3P)

- ^ a b c d e "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: (2012 VP113)" (last observation: 2013-10-30 (arc=~2 year)). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 9 June 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Malhotra, Renu; Volk, Kathryn; Wang, Xianyu (2016). "Corralling a distant planet with extreme resonant Kuiper belt objects". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 824 (2): L22. arXiv:1603.02196. Bibcode:2016ApJ...824L..22M. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/824/2/L22.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Horizons output. "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements for 90377 Sedna (2003 VB12)". Retrieved 18 September 2021. (Solution using the Solar System barycenter. Select Ephemeris Type:Elements and Center:@0) (Saved Horizons output file 2011-Feb-04 "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements for 90377 Sedna". Archived from the original on 19 November 2012.) In the second pane "PR=" can be found, which gives the orbital period in days (4.160E+06, which is 11,390 Julian years). Cite error: The named reference "barycenter" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f Lakdawalla, Emily (26 March 2014). "A second Sedna! What does it mean?". Planetary Society blogs. The Planetary Society. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Trujillo, C. A.; Sheppard, S. S. (2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–474. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.1038/nature13156. PMID 24670765. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Brown, Michael E. (17 April 2014). "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system? (updates daily)". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d "2012 VP113 Orbit" (arc=739 days over 3 oppositions). IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Witze, Alexandra (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet stretches Solar System's edge". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14921.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (26 March 2014). "A New Planetoid Reported in Far Reaches of Solar System". New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b Sheppard, Scott S. "Beyond the Edge of the Solar System: The Inner Oort Cloud Population". Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Carnegie Institution for Science. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Sample, Ian (26 March 2014). "Dwarf planet discovery hints at a hidden Super Earth in solar system". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ a b c "NASA Supported Research Helps Redefine Solar System's Edge". NASA. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ^ a b "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: q > 47 (AU)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Wall, Mike (26 March 2014). "New Dwarf Planet Found at Solar System's Edge, Hints at Possible Faraway 'Planet X'". Space.com web site. TechMediaNetwork. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "A new object at the edge of our Solar System discovered". Physorg.com. 26 March 2014.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (1 September 2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Aarseth, S. J. (11 January 2015). "Flipping minor bodies: what comet 96P/Machholz 1 can tell us about the orbital evolution of extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the production of near-Earth objects on retrograde orbits". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 446 (2): 1867–1873. arXiv:1410.6307. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.446.1867D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2230.

- ^ "MPEC 2021-C187 : 2018 AG37". Minor Planet Electronic Circular. Minor Planet Center. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Most Distant Object In Solar System Discovered; NASA.gov; (2004)

- ^ a b "AstDyS-2, Asteroids – Dynamic Site". Retrieved 17 December 2021.

Objects with distance from Sun over 65 AU

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. "JPL Horizons On-Line Ephemeris". Retrieved 10 February 2021.

Ephemeris Type: Vector; Observer Location: @sun; Time Span: Start=2015-12-01, Stop=2021-06-01, Intervals=1; Table Settings: quantities code=6 - ^ a b "Voyager - Hyperbolic Orbital Elements".

External links

- 2012 VP113 Inner Oort Cloud Object Discovery Images from Scott S. Sheppard/Carnegie Institution for Science.

- 2012 VP113 has Q=460 ± 30 (mpml: CFHT 2011-Oct-22 precovery)

- 2012 VP113 at the JPL Small-Body Database