Thoth

| ḏḥwtj Thoth | |

|---|---|

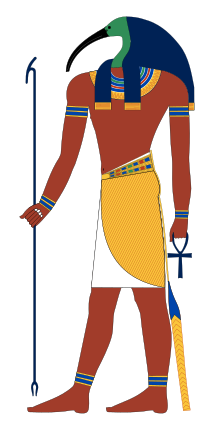

Thoth, in one of his forms as an ibis-headed man | |

| Major cult center | Hermopolis |

| Symbol | Ibis, moon disk, papyrus scroll, reed pens, writing palette, stylus, baboon, scales |

| Consort | Maat |

| Offspring | Seshat[a] |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek | Hermes |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Thoth (/θoʊθ, toʊt/; from Template:Lang-grc-koi Thṓth, borrowed from Template:Lang-cop Thōout, Egyptian 𓅞𓏏𓏭𓀭 Ḏḥwtj, the reflex of Template:Lang-egy "[He] is like the Ibis") is an ancient Egyptian deity. In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine counterpart was Seshat, and his wife was Ma'at.[1] He was the god of the moon, wisdom, writing, hieroglyphs, science, magic, art, and judgment. His Greek equivalent is Hermes.

Thoth's chief temple was located in the city of Hermopolis (Template:Lang-egy /χaˈmaːnaw/, Egyptological pronunciation: "Khemenu", Template:Lang-cop Shmun). Later known as el-Ashmunein in Egyptian Arabic, the Temple of Thoth was mostly destroyed before the beginning of the Christian era, but its very large pronaos was still standing in 1826.[2]

In Hermopolis, Thoth led "the Ogdoad", a pantheon of eight principal deities, and his spouse was Nehmetawy. He also had numerous shrines in other cities.[3]

Thoth played many vital and prominent roles in Egyptian mythology, such as maintaining the universe, and being one of the two deities (the other being Ma'at) who stood on either side of Ra's solar barque.[4] In the later history of ancient Egypt, Thoth became heavily associated with the arbitration of godly disputes,[5] the arts of magic, the system of writing, and the judgment of the dead.[6]

Name

or

| ||||||||||

| Common names for Thoth[7] in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Egyptian pronunciation of ḏḥwty is not fully known, but may be reconstructed as *ḏiḥautī, perhaps pronounced *[t͡ʃʼi.ˈħau.tʰiː] or *[ci.ˈħau.tʰiː]. This reconstruction is based on the Ancient Greek borrowing Thōth ([tʰɔːtʰ]) or Theut and the fact that the name was transliterated into Sahidic Coptic variously as ⲑⲟⲟⲩⲧ Thoout, ⲑⲱⲑ Thōth, ⲑⲟⲟⲧ Thoot, ⲑⲁⲩⲧ Thaut, Taautos (Τααυτος), Thoor (Θωωρ), as well as Bohairic Coptic ⲑⲱⲟⲩⲧ Thōout. These spellings reflect known sound changes from earlier Egyptian such as the loss of ḏ palatalization and merger of ḥ with h i.e. initial ḏḥ > th > tʰ.[8] The loss of pre-Coptic final y/j is also common.[9] Following Egyptological convention, which eschews vowel reconstruction, the consonant skeleton ḏḥwty would be rendered "Djehuti" and the god is sometimes found under this name. However, the Greek form "Thoth" is more common.

According to Theodor Hopfner,[10] Thoth's Egyptian name written as ḏḥwty originated from ḏḥw, claimed to be the oldest known name for the ibis, normally written as hbj. The addition of -ty denotes that he possessed the attributes of the ibis.[11] Hence Thoth's name would mean "He who is like the ibis", according to this interpretation.

Further names and spellings

Other forms of the name ḏḥwty using older transcriptions include Jehuti, Jehuty, Tahuti, Tehuti, Zehuti, Techu, or Tetu. Multiple titles for Thoth, similar to the pharaonic titulary, are also known, including A, Sheps, Lord of Khemennu, Asten, Khenti, Mehi, Hab, and A'an.[12]

In addition, Thoth was also known by specific aspects of himself, for instance the Moon god Iah-Djehuty (j3ḥ-ḏḥw.ty), representing the Moon for the entire month.[13] The Greeks related Thoth to their god Hermes due to his similar attributes and functions.[14] One of Thoth's titles, "Thrice great", was translated to the Greek τρισμέγιστος (trismégistos), making Hermes Trismegistus.[15][16]

Depictions

Thoth has been depicted in many ways depending on the era and on the aspect the artist wished to convey. Usually, he is depicted in his human form with the head of an ibis.[17] In this form, he can be represented as the reckoner of times and seasons by a headdress of the lunar disk sitting on top of a crescent moon resting on his head. When depicted as a form of Shu or Ankher, he was depicted to be wearing the respective god's headdress. Sometimes he was also seen in art to be wearing the Atef crown or the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.[11] When not depicted in this common form, he sometimes takes the form of the ibis directly.[17]

He also appears as a dog-faced baboon or a man with the head of a baboon when he is A'an, the god of equilibrium.[18] In the form of A'ah-Djehuty he took a more human-looking form.[19] These forms are all symbolic and are metaphors for Thoth's attributes. Thoth is often depicted holding an ankh, the Egyptian symbol for life.

Attributes

Thoth's roles in Egyptian mythology were many. He served as scribe of the gods,[20] credited with the invention of writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs.[21] In the underworld, Duat, he appeared as an ape, Aani, the god of equilibrium, who reported when the scales weighing the deceased's heart against the feather, representing the principle of Maat, was exactly even.[22]

The ancient Egyptians regarded Thoth as One, self-begotten, and self-produced.[17] He was the master of both physical and moral (i.e. divine) law,[17] making proper use of Ma'at.[23] He is credited with making the calculations for the establishment of the heavens, stars, Earth,[24] and everything in them.[23]

The Egyptians credited him as the author of all works of science, religion, philosophy, and magic.[25] The Greeks further declared him the inventor of astronomy, astrology, the science of numbers, mathematics, geometry, surveying, medicine, botany, theology, civilized government, the alphabet, reading, writing, and oratory. They further claimed he was the true author of every work of every branch of knowledge, human and divine.[21]

Mythology

Egyptian mythology credits Thoth with the creation of the 365-day calendar. Originally, according to the myth, the year was only 360 days long and Nut was sterile during these days, unable to bear children. Thoth gambled with the Moon for 1/72nd of its light (360/72 = 5), or 5 days, and won. During these 5 days, Nut and Geb gave birth to Osiris, Set, Isis, and Nephthys.

In the central Osiris myth, Thoth gives Isis the words to restore her husband, allowing the pair to conceive Horus. Following a battle between Horus and Set, Thoth offers counsel and provides wisdom.

History

Thoth was a Moon god. The Moon not only provides light at night, allowing time to still be measured without the sun, but its phases and prominence gave it a significant importance in early astrology/astronomy. The perceived cycles of the Moon also organized much of Egyptian society's rituals and events, both civil and religious. Consequently, Thoth gradually became seen as a god of wisdom, magic, and the measurement and regulation of events and of time.[27] He was thus said to be the secretary and counselor of the sun god Ra, and with Ma'at (truth/order) stood next to Ra on the nightly voyage across the sky.

Thoth became credited by the ancient Egyptians as the inventor of writing (hieroglyphs),[28] and was also considered to have been the scribe of the underworld. For this reason, Thoth was universally worshipped by ancient Egyptian scribes. Many scribes had a painting or a picture of Thoth in their "office". Likewise, one of the symbols for scribes was that of the ibis.

In art, Thoth was usually depicted with the head of an ibis, possibly because the Egyptians saw the curve of the ibis' beak as a symbol of the crescent moon.[29] Sometimes, he was depicted as a baboon holding up a crescent moon.

During the Late Period of ancient Egypt, a cult of Thoth gained prominence due to its main center, Khmun (Hermopolis Magna), also becoming the capital. Millions of dead ibis were mummified and buried in his honor.[30]

Thoth was inserted in many tales as the wise counselor and persuader, and his association with learning and measurement led him to be connected with Seshat, the earlier deification of wisdom, who was said to be his daughter, or variably his wife. Thoth's qualities also led to him being identified by the Greeks with their closest matching god Hermes, with whom Thoth was eventually combined as Hermes Trismegistus,[31] leading to the Greeks' naming Thoth's cult center as Hermopolis, meaning city of Hermes.

In the Papyrus of Ani copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead the scribe proclaims "I am thy writing palette, O Thoth, and I have brought unto thee thine ink-jar. I am not of those who work iniquity in their secret places; let not evil happen unto me."[32] Plate XXIX Chapter CLXXV (Budge) of the Book of the Dead is the oldest tradition said to be the work of Thoth himself.[33]

There was also an Egyptian pharaoh of the Sixteenth dynasty named Djehuty (Thoth) after him, and who reigned for three years.

Plato mentions Thoth in his dialogue, Phaedrus. He uses the myth of Thoth to demonstrate that writing leads to laziness and forgetfulness. In the story, Thoth remarks to King Thamus of Egypt that writing is a wonderful substitute for memory. Thamus remarks that it is a remedy for reminding, not remembering, with the appearance but not the reality of wisdom. Future generations will hear much without being properly taught and will appear wise but not be so.

Artapanus of Alexandria, an Egyptian Jew who lived in the third or second century BC, euhemerized Thoth-Hermes as a historical human being and claimed he was the same person as Moses, based primarily on their shared roles as authors of texts and creators of laws. Artapanus's biography of Moses conflates traditions about Moses and Thoth and invents many details.[34] Many later authors, from late antiquity to the Renaissance, either identified Hermes Trismegistus with Moses or regarded them as contemporaries who expounded similar beliefs.[35]

Archaeology

Egypt’s Minister of Tourism and Antiquities announced the discovery of the collective graves of senior officials and high clergies of the god Thoth in Tuna el-Gebel in Minya in January 2020. An archaeological mission headed by Mostafa Waziri reported that 20 sarcophagi and coffins of various shapes and sizes, including five anthropoid sarcophagi made of limestone and carved with hieroglyphic texts, as well as 16 tombs and five well-preserved wooden coffins were unearthed by their team.[36][37]

Modern cultural references

Thoth has been seen as a god of wisdom and has been used in modern literature, especially since the early 20th century when ancient Egyptian ideas were quite popular.

- In Croyd by Ian Wallace (Berkeley Medallion, 1968), Thoth is the father of the Galactic Agent hero, Croyd.

- Aleister Crowley's Egyptian style Thoth tarot deck and its written description in his 1944 book The Book of Thoth were named in reference to the theory that Tarot cards were the Egyptian book of Thoth.

- H. P. Lovecraft also used the word "Thoth" as the basis for his alien god, "Yog-Sothoth", an entity associated with sorcery and esoteric knowledge.[38]

- Thoth is mentioned as one of the pantheon in the 1831 issue of The Wicked + The Divine.

- In the 2016 film Gods of Egypt, Thoth is played by Chadwick Boseman.[39]

- Thoth is also a recurring character in The Kane Chronicles book series.[citation needed]

- Thoth's papyrus plays a central part in the book Scroll of Saqqara.[40]

- Thoth appears in the 2021 comic book series God of War: Fallen God,[41] which is based on the God of War video game franchise.

- In the 2002 Ensemble Studios game Age of Mythology, Thoth is one of 9 minor gods that can be worshipped by Egyptian players.[42][43]

- Thoth is one of many playable gods in Hi-Rez Studios' third-person multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) video game Smite.[44]

- In the third part of JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Stardust Crusaders, Thoth is a stand in a form of a manga, able to predict the future whose user is Boingo, member of Egypt 9 Glory Gods.

See also

- Eye of Horus

- The Book of Thoth

- The Book of Thoth (Crowley)

- Thout, the first month of the Coptic calendar

- List of lunar deities

- Phaedrus (dialogue)

Notes

- ^ Also said to be his consort.

References

- ^ Thutmose III: A New Biography By Eric H Cline, David O'Connor University of Michigan Press (January 5, 2006)p. 127

- ^ Verner, Miroslav (2013). Temple of the World: Sanctuaries, Cults, and Mysteries of Ancient Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-977-416-563-4.

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Thoth was said to be born from the skull of Set also said to be born from the heart of Ra.p. 401)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 400)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 405)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 403)

- ^ Hieroglyphs verified, in part, in (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402) and (Collier and Manley p. 161)

- ^ Allen, James P. (11 July 2013). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107032460.

- ^ Allen, James P. (11 July 2013). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107032460.

- ^ Hopfner, Theodor, b. 1886. Der tierkult der alten Agypter nach den griechisch-romischen berichten und den wichtigeren denkmalern. Wien, In kommission bei A. Holder, 1913. Call#= 060 VPD v.57

- ^ a b (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 402)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 402–3)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 pp. 412–3)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians p. 402)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 415)

- ^ A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in Bull, Christian H. 2018. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33–96.

- ^ a b c d (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- ^ (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 plate between pp. 408–9)

- ^ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 408)

- ^ a b (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 414)

- ^ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 403)

- ^ a b (Budge The Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 407)

- ^ (Budge Gods of the Egyptians Vol. 1 p. 401)

- ^ (Hall The Hermetic Marriage p. 224)

- ^ "Museum item, accession number: 36.106.2". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Assmann, Jan, The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, 2001, pp. 80–81

- ^ Littleton, C.Scott (2002). Mythology. The illustrated anthology of world myth & storytelling. London: Duncan Baird Publishers. pp. 24. ISBN 9781903296370.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard H., The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, 2003, p. 217

- ^ Wasef, Sally; Subramanian, Sankar; O'Rorke, Richard; Huynen, Leon; El-Marghani, Samia; Curtis, Caitlin; Popinga, Alex; Holland, Barbara; Ikram, Salima; Millar, Craig; Willerslev, Eske; Lambert, David (2019). "Mitogenomic diversity in Sacred Ibis Mummies sheds light on early Egyptian practices". PLOS ONE. 14 (11): e0223964. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423964W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223964. PMC 6853290. PMID 31721774.

- ^ A survey of the literary and archaeological evidence for the background of Hermes Trismegistus in the Greek Hermes and the Egyptian Thoth may be found in Bull, Christian H. 2018. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Leiden: Brill, pp. 33–96.

- ^ The Book of the Dead by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1895, Gramercy, 1999, p. 562, ISBN 0-517-12283-9

- ^ The Book of the Dead by E. A. Wallis Budge, 1895, Gramercy, 1999, p. 282, ISBN 0-517-12283-9

- ^ Mussies, Gerald (1982), "The Interpretatio Judaica of Thot-Hermes", in van Voss, Heerma, et al. (eds.) Studies in Egyptian Religion Dedicated to Professor Jan Zandee, pp. 91, 97, 99–100

- ^ Mussies (1982), pp. 118–120

- ^ "In photos: Communal tombs for high priests uncovered Upper Egypt – Ancient Egypt – Heritage". Ahram Online. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Tombs of High Priests Discovered in Upper Egypt – Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Steadman, John L. (1 September 2015). H. P. Lovecraft and the Black Magickal Tradition: The Master of Horror's Influence on Modern Occultism. Weiser Books. ISBN 9781633410008.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (13 November 2015). "Gods of Egypt posters spark anger with 'whitewashed' cast". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Gedges, Pauline (4 September 2007). Scroll of Saqqara. Penguin Canada. ISBN 978-0143167440.

- ^ Sawan, Amer (14 June 2021). "God of War: Kratos Comes Face to Face With Brand New Pantheon". CBR.com. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ "The Minor Gods: Egyptian – Age of Mythology Wiki Guide – IGN".

- ^ "Age of Mythology".

- ^ www.smitegame.com https://www.smitegame.com/gods/. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Bleeker, Claas Jouco. 1973. Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion. Studies in the History of Religions 26. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Boylan, Patrick. 1922. Thoth, the Hermes of Egypt: A Study of Some Aspects of Theological Thought in Ancient Egypt. London: Oxford University Press. (Reprinted Chicago: Ares Publishers inc., 1979).

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. Egyptian Religion. Kessinger Publishing, 1900.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The Gods of the Egyptians Volume 1 of 2. New York: Dover Publications, 1969 (original in 1904).

- Jaroslav Černý. 1948. "Thoth as Creator of Languages." Journal of Egyptian Archæology 34:121–122.

- Collier, Mark and Manley, Bill. How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: Revised Edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Fowden, Garth. 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Mind. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. (Reprinted Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993). ISBN 0-691-02498-7.

- The Book of Thoth, by Aleister Crowley. (200 signed copies, 1944) Reprinted by Samuel Wiser, Inc 1969, first paperback edition, 1974 (accompanied by The Thoth Tarot Deck, by Aleister Crowley & Lady Fred Harris)

External links

- Stadler, Martin (2012). "Thoth". In Dieleman, Jacco; Wendrich, Willeke (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles.