Led Zeppelin IV

| Untitled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 8 November 1971 | |||

| Recorded | ||||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:20 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Producer | Jimmy Page | |||

| Led Zeppelin chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Led Zeppelin IV | ||||

| ||||

The untitled fourth studio album by the English rock band Led Zeppelin, commonly known as Led Zeppelin IV,[a] was released on 8 November 1971 by Atlantic Records. It was produced by guitarist Jimmy Page and recorded between December 1970 and February 1971, mostly in the country house Headley Grange. The album is notable for featuring "Stairway to Heaven", which has been described as the band's signature song.[4]

The informal setting at Headley Grange inspired the band, allowing them to try different arrangements of material and create songs in various styles. After the band's previous album Led Zeppelin III received lukewarm reviews from critics, they decided their fourth album would officially be untitled and would be represented instead by four symbols chosen by each band member, without featuring the name or any other details on the cover. Unlike the prior two albums, the band was joined by some guest musicians, such as vocalist Sandy Denny on "The Battle of Evermore", and pianist Ian Stewart on "Rock and Roll". As with prior albums, most of the material was written by the band, though there was one cover song, a hard rock re-interpretation of the Memphis Minnie blues song "When the Levee Breaks".

The album was a commercial and critical success and is Led Zeppelin's best-selling album, shipping over 37 million copies worldwide. It is one of the best-selling albums in the US, while critics have regularly placed it highly on lists of the greatest albums of all time. In 2010, Led Zeppelin IV was one of ten classic album covers from British artists commemorated on a UK postage stamp issued by the Royal Mail.[5][6]

Writing and recording

Following the release of Led Zeppelin III in October 1970, the group took a break from live performances to concentrate on recording a follow-up. They turned down all touring offers, including a proposed New Year's Eve gig that would have been broadcast by television. They returned to Bron-Yr-Aur, a country house in Snowdonia, Wales, to write new material.[7]

Recording sessions for the album began at Island Records' new Basing Street studios in London on 5 December 1970, with the recording of "Black Dog".[8][9] The group had considered Mick Jagger's home, Stargroves as a recording location, but decided it was too expensive.[10] They subsequently moved the following month to Headley Grange, a country house in Hampshire, England, using the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio and engineer Andy Johns, with the Stones' Ian Stewart assisting. Johns had just worked on engineering Sticky Fingers and recommended the mobile studio.[10] Guitarist and producer Jimmy Page later recalled: "We needed the sort of facilities where we could have a cup of tea and wander around the garden and go in and do what we had to do."[11] This relaxed, atmospheric environment at Headley Grange also provided other advantages for the band, as they were able to capture spontaneous performances immediately, with some tracks arising from the communal jamming.[11] Bassist and keyboardist John Paul Jones remembered there was no bar or leisure facilities, but this helped focus the group on the music without being distracted.[10]

Once the basic tracks had been recorded, the band added overdubs at Island Studios in February. The band spent five days at Island, before Page then took the multitrack tapes to Sunset Sound in Los Angeles for mixing on 9 February, on Johns' recommendation, with a plan for an April 1971 release.[12][13][8] Mixing would take ten days, before Page travelled back to London with the newly mixed material. The band had a playback at Olympic Studios.[8] The band disliked the results, and so after touring through the spring and early summer, Page remixed the whole album in July. The album was delayed again over the choice of cover, whether it should be a double album, with a possible suggestion it could be issued as a set of EPs.[14]

Songs

Side one

"Black Dog" was named after a dog that hung around Headley Grange during recording. The riff was written by Page and Jones, while the a cappella section was influenced by Fleetwood Mac's "Oh Well". Vocalist Robert Plant wrote the lyrics, and later sang portions of the song during solo concerts.[3] The guitar solos on the outro were recorded directly into the desk, without using an amplifier.[15]

"Rock and Roll" was a collaboration with Stewart that came out of a jam early in the recording sessions at Headley Grange. Drummer John Bonham wrote the introduction, which came from jamming around the intro to Little Richard's "Keep A-Knockin'".[16] The track became a live favourite in concert, being performed as the opening number or an encore.[3] It was released as a promotional single in the US, with stereo and mono mixes on either side of the disc.[17]

"The Battle of Evermore" was written by Page on the mandolin, borrowed from Jones. Plant added lyrics inspired by a book he was reading about the Scottish Independence Wars. The track features a duet between Plant and Fairport Convention's Sandy Denny, [18][b] who provides the only female voice to be heard on a Led Zeppelin recording.[20] Plant played the role of narrator in the song, describing events, while Denny sang the part of the town crier representing the people.[19]

"Stairway to Heaven" was mostly written by Page, and the bulk of the chord sequence was already worked out when recording started at Basing Street Studios. The lyrics were written by Plant at Headley Grange, about a woman who "took everything without giving anything back".[21] The final take of the song was recorded at Island Studios after the Headley Grange session. The basic backing track featured Bonham on drums, Jones on electric piano and Page on acoustic guitar.[21] The whole group contributed to the arrangement, such as Jones playing recorders on the introduction and Bonham's distinctive drum entry halfway through the piece.[18] Page played the guitar solo using a Fender Telecaster he had received from Jeff Beck and had been his main guitar on the group's first album and early live shows. He put down three different takes of the solo and picked the best to put on the album.[22]

The song was considered the standout track on the album and was played on FM radio stations frequently, but the group resisted all suggestions to release it as a single. It became the centrepiece of the group's live set from 1971 onwards; in order to replicate the changes between acoustic, electric and twelve-string guitar on the studio recording, Page played a Gibson EDS-1275 double-neck guitar during the song.[18]

Side two

"Misty Mountain Hop" was written at Headley Grange and featured Jones playing electric piano.[18] Plant wrote the lyrics about dealing with the clash between students and police over drug possession. The title comes from J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit.[23] Plant later performed the track on solo tours.[18]

"Four Sticks" took its title from Bonham playing the drum pattern that runs throughout the song with four drum sticks, and Jones played analog synth. The track was difficult to record compared to the other material on the album, requiring numerous takes.[18] It was played live only once by Led Zeppelin,[18] and re-recorded with the Bombay Symphony Orchestra in 1972.[24] It was reworked for Page and Plant's 1994 album No Quarter: Jimmy Page and Robert Plant Unledded.[25]

"Going to California" is a quiet acoustic number. It was written by Page and Plant about Californian earthquakes, and trying to find the perfect woman. The music was inspired by Joni Mitchell, of whom both Plant and Page were fans. The track was originally titled "Guide To California"; the final title comes from the trip to Los Angeles to mix the album.[18][26]

"When the Levee Breaks" comes from a blues song recorded by Memphis Minnie and Kansas Joe McCoy in 1929. The track opens with Bonham's heavy unaccompanied drumming, which was recorded in the lobby of Headley Grange using two Beyerdynamic M 160 microphones which were hung up a flight of stairs; output from these were passed to a limiter. A Binson Echorec, a delay effects unit, was also used.[27] Page recalled he had tried to record the track at early sessions, but it had sounded flat. The unusual locations around the lobby gave the ideal ambience for the drum sound.[28] This introduction was later extensively sampled for hip hop music in the 1980s.[18] Page and Plant played the song on their 1995 tour promoting No Quarter: Jimmy Page and Robert Plant Unledded.[29]

Other songs

Three other songs from the sessions, "Down by the Seaside", "Night Flight" and "Boogie with Stu" (featuring Stewart on piano), were included four years later on the double album Physical Graffiti. An early version of "No Quarter" was also recorded at the sessions.[18]

Title

After the lukewarm, if not confused and sometimes dismissive, critical reaction Led Zeppelin III had received in late 1970, Page decided that the next Led Zeppelin album would not have a title, but would instead feature four hand-drawn symbols on the inner sleeve and record label, each one chosen by the band member it represents.[3] The record company were strongly against the idea, but the group stood their ground and refused to hand over the master tapes until their decision had been agreed to.[30]

Page has also stated that the decision to release the album without any written information on the album sleeve was contrary to strong advice given to him by a press agent, who said that after a year's absence from both records and touring, the move would be akin to "professional suicide".[31] Page thought, "We just happened to have a lot of faith in what we were doing."[31] He recalled the record company were insisting that a title had to be on the album, but held his ground, as he felt it would be an answer to critics who could not review one Led Zeppelin album without a point of reference to earlier ones.[32]

Releasing the album without an official title has made it difficult to consistently identify. While most commonly called Led Zeppelin IV, Atlantic Records catalogues have used the names Four Symbols and The Fourth Album. It has also been referred to as ZoSo (which Page's symbol appears to spell), Untitled and Runes.[3] Page frequently refers to the album in interviews as "the fourth album" and "Led Zeppelin IV",[31] and Plant thinks of it as "the fourth album, that's it".[33] The original LP also has no text on the front or back cover, and lacks a catalogue number on the spine.[3]

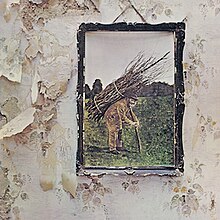

Cover

In place of a title, Page decided each member could choose a personal emblem for the cover. Initially thinking of a single symbol, he then decided there could be four, with each member of the band choosing his own.[31] He designed his own symbol[3] and has never publicly disclosed any reasoning behind it. It has been argued that his symbol appeared as early as 1557 to represent Saturn.[34] The symbol is sometimes referred to as "ZoSo", though Page has explained that it was not in fact intended to be a word at all.[3] Jones' symbol, which he chose from Rudolf Koch's Book of Signs, is a single circle intersecting three vesica pisces (a triquetra). It is intended to symbolise a person who possesses both confidence and competence.[3] Bonham's symbol, the three interlocking (Borromean) rings, was picked by the drummer from the same book. It represents the triad of mother, father and child, but, also happens to be the logo for the Gun Producer Krupp and, turned upside down, Ballantine beer.[3] Plant's symbol of a feather within a circle was his own design, being based on the sign of the supposed Mu civilisation.[3] A fifth, smaller symbol chosen by guest vocalist Sandy Denny represents her contribution to "The Battle of Evermore"; the figure, composed of three equilateral triangles, appears on the inner sleeve of the LP, serving as an asterisk.[35]

During Led Zeppelin's tour of the United Kingdom in winter 1971 shortly after the album's release, the symbols could be seen on the group's stage equipment; Page's on one of his amplifiers, Bonham's on his bass drum head, Jones' on a covering for his Rhodes piano, and Plant's on the side of a PA cabinet. Only Page's and Bonham's symbols were retained for subsequent tours.[36][37]

The 19th-century rustic oil painting on the front of the album was purchased from an antique shop in Reading, Berkshire by Plant.[3][38] The painting was then juxtaposed and affixed to the internal, papered wall of a partly demolished suburban house for the photograph to be taken. The block of flats seen on the album is the Salisbury Tower in the Ladywood district of Birmingham.[39] Page has explained that the cover of the fourth album was intended to bring out a city/country dichotomy that had initially surfaced on Led Zeppelin III, and a reminder that people should look after the Earth.[31] He later said the cover was supposed to be for "other people to savour" rather than a direct statement.[40] The album cover was among the 10 chosen by the Royal Mail for a set of "Classic Album Cover" postage stamps issued in January 2010.[41]

The inside illustration, entitled "The Hermit", painted by Barrington Coleby (credited to Barrington Colby MOM on the album sleeve),[35] was influenced by the design of the card of the same name in the Rider–Waite tarot deck.[3] This character was later portrayed by Page himself in Led Zeppelin's concert film, The Song Remains the Same (1976).[42] The inner painting is also referred to as View in Half or Varying Light.[43] The typeface for the lyrics to "Stairway to Heaven", printed on the inside sleeve of the album, was Page's contribution. He found it in an old arts and crafts magazine called The Studio which dated from the late 19th century. He thought the lettering was interesting and arranged for someone to create a whole alphabet.[38]

Release

The album was released by Atlantic on 8 November 1971.[1] It was promoted via a series of teaser advertisements showing the individual symbols on the album artwork.[3] It entered the UK chart at No. 10, rising to No.1 the following week and has spent a total of 90 weeks on the chart.[44] In the US it was Led Zeppelin's best-selling album,[45] but did not top the Billboard album chart, peaking at No. 2 behind There's a Riot Goin' On by Sly and the Family Stone and Music by Carole King.[46][47][c] "Ultimately", writes Lewis, "the fourth Zeppelin album would be the most durable seller in their catalogue and the most impressive critical and commercial success of their career".[3] At one point, it was ranked as one of the top five best-selling albums of all time.[49] The album is one of the best-selling albums of all time with more than 37 million copies sold as of 2014.[50] As of 2021, it is tied for fifth-highest-certified album in the US by the Recording Industry Association of America at 24× Platinum.[51]

The album was reissued several times throughout the 1970s, including a lilac vinyl pressing in 1978, and a box set package in 1988.[52] It was first issued on CD in the 1980s. Page remastered the album in 1990 with engineer George Marino in an attempt to update the catalogue, and several tracks were used for that year's compilation Led Zeppelin Remasters and the Led Zeppelin Boxed Set. All remastered tracks were reissued on The Complete Studio Recordings,[53] while the album was individually reissued on CD in 1994.[54][55]

A remastered version of Led Zeppelin IV was reissued on 27 October 2014, along with Houses of the Holy. The reissue comes in six formats: a standard CD edition, a deluxe two-CD edition, a standard LP version, a deluxe two-LP version, a super deluxe two-CD plus two-LP version with a hardback book, and as high-resolution 24-bit/96k digital downloads. The deluxe and super deluxe editions feature bonus material. The reissue was released with an inverted colour version of the original album's artwork as its bonus disc's cover.[56] The album's remastered version received widespread acclaim from critics, including Rolling Stone, who found Page's remastering "illuminative".[57]

Critical reception

| Retrospective professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 100/100[58] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A[61] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A+[63] |

| Mojo | |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[65] |

| Pitchfork | 9.1/10[66] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Led Zeppelin IV received overwhelming praise from critics.[49] In a contemporary review for Rolling Stone, Lenny Kaye called it the band's "most consistently good" album yet and praised the diversity of the songs: "out of eight cuts, there isn't one that steps on another's toes, that tries to do too much all at once."[69] Billboard magazine called it a "powerhouse album" that has the commercial potential of the band's previous three albums.[70] Robert Christgau originally gave Led Zeppelin IV a lukewarm review in The Village Voice, but later called it a masterpiece of "heavy rock".[71] While still finding the band's medieval ideas limiting, he believed the album showed them at the pinnacle of their songwriting,[72] and regarded it as "the definitive Led Zeppelin and hence heavy metal album".[61]

In a retrospective review for AllMusic, Stephen Thomas Erlewine credited the album for "defining not only Led Zeppelin but the sound and style of '70s hard rock", while "encompassing heavy metal, folk, pure rock & roll, and blues".[59] In his album guide to heavy metal, Spin magazine's Joe Gross cited Led Zeppelin IV as a "monolithic cornerstone" of the genre.[73] BBC Music's Daryl Easlea said that the album made the band a global success and effectively combined their third album's folk ideas with their second album's hard rock style,[74] while Katherine Flynn and Julian Ring of Consequence of Sound felt it featured their debut's blues rock, along with the other styles from their second and third albums.[75] Led Zeppelin's Rock and Roll Hall of Fame biography described the album as "a fully realized hybrid of the folk and hard-rock directions".[76] PopMatters journalist AJ Ramirez regarded it as one of the greatest heavy metal albums ever,[77] while Chuck Eddy named it the number one metal album of all time in his 1991 book Stairway to Hell: The 500 Best Heavy Metal Albums in the Universe.[78] According to rock scholar Mablen Jones, Led Zeppelin IV and particularly "Stairway to Heaven" reflected heavy metal's presence in countercultural trends of the early 1970s, as the album "blended post-hippie mysticism, mythological preoccupations, and hard rock".[79]

Steven Hyden observed in 2018 that the album's popularity had given rise to a reflexive bias against it from both fans and critics. "There are two unwritten laws" about the album, he wrote. The first was that a listener must claim a track from side two, the "deep cuts with credibility" side, was his or her favorite, and the second was that one should never say it was their favorite among the band's albums. He blamed this later tendency for why "rock critics who try too hard always make a case for In Through the Out Door being Zeppelin's best." The band members themselves, he noted, also seemed to prefer performing the songs from side two in their solo shows.[80]

Accolades

In 2000, Led Zeppelin IV was named the 26th-greatest British album in a list by Q magazine.[81] In 2002, Spin magazine's Chuck Klosterman named it the second-greatest metal album of all time and said that it was "the most famous hard-rock album ever recorded" as well as an album that unintentionally created metal—"the origin of everything that sounds, feels, or even tastes vaguely metallic".[82] In 2000 it was voted number 42 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[83] In 2003, the album was ranked number 66 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time", then re-ranked number 69 in a 2012 revised list,[84] and re-ranked 58 in a 2020 revised list.[85] It was also named the seventh-best album of the 1970s in a list by Pitchfork.[86] In 2016, Classic Rock magazine ranked Led Zeppelin IV as the greatest of all Zeppelin albums.[87]

| Accolade | Publication | Country | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made"[88] | Mojo | UK | 1996 | 24 |

| Grammy Hall of Fame Award[89] | Grammy Awards | US | 1999 | * |

| "Album of the Millennium"[90] | The Guitar | US | 1999 | 2 |

| "100 Greatest Rock Albums Ever"[91] | Classic Rock | UK | 2001 | 1 |

| "500 Greatest Albums Ever"[85] | Rolling Stone | US | 2020 | 58 |

| "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s"[86] | Pitchfork | US | 2004 | 7 |

| 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[92] | Robert Dimery | US | 2005 | * |

| "100 Best Albums Ever"[93] | Q | UK | 2006 | 21 |

| "100 Greatest British Rock Albums Ever"[94] | Classic Rock | UK | 2006 | 1 |

| "The Definitive 200: Top 200 Albums of All-Time"[95] | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | US | 2007 | 4 |

| NME's The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[96] | NME | UK | 2013 | 106 |

* designates unordered lists.

Track listing

Original release

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Black Dog" | 4:55 | |

| 2. | "Rock and Roll" |

| 3:40 |

| 3. | "The Battle of Evermore" |

| 5:38 |

| 4. | "Stairway to Heaven" |

| 7:55 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Misty Mountain Hop" |

| 4:39 |

| 2. | "Four Sticks" |

| 4:49 |

| 3. | "Going to California" |

| 3:36 |

| 4. | "When the Levee Breaks" |

| 7:08 |

| Total length: | 42:20 | ||

Deluxe edition (2014)

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Black Dog" (Basic track with guitar overdubs) | 4:34 |

| 2. | "Rock and Roll" (Alternate mix) | 3:39 |

| 3. | "The Battle of Evermore" (Mandolin/Guitar mix from Headley Grange) | 4:13 |

| 4. | "Stairway to Heaven" (Sunset Sound mix) | 8:03 |

| 5. | "Misty Mountain Hop" (Alternate mix) | 4:45 |

| 6. | "Four Sticks" (Alternate mix) | 4:33 |

| 7. | "Going to California" (Mandolin/Guitar mix) | 3:34 |

| 8. | "When the Levee Breaks" (Alternate UK mix) | 7:08 |

| Total length: | 40:32 | |

Personnel

|

Led Zeppelin

Additional musicians

|

Production

|

Charts

Weekly charts

| Chart (1971–72) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums Chart[100] | 2 |

| Austrian Album Chart[101] | 3 |

| Canadian Albums Chart[102] | 1 |

| Danish Albums Chart[103] | 2 |

| Dutch Album Chart[104] | 1 |

| Finnish Album Chart[105] | 7 |

| French Album Chart[106] | 2 |

| German Album Chart[107] | 5 |

| Norwegian Album Chart[108] | 3 |

| Spanish Albums Chart[109] | 8 |

| Swedish Album Chart[110] | 2 |

| UK Albums Chart[52] | 1 |

| US Billboard 200[46] | 2 |

| US Cash Box Top 100 Albums[111] | 1 |

| US Record World Album Chart[112] | 1 |

| Chart (2014) | Peak position |

| Hungarian Albums (MAHASZ)[113] | 13 |

| Polish Albums (ZPAV)[114] | 18 |

Year-end charts

| Chart (1972) | Position |

|---|---|

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[115] | 27 |

| Chart (2002) | Position |

| Canadian Metal Albums (Nielsen SoundScan)[116] | 67 |

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[117] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[118] | 9× Platinum | 630,000^ |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[119] | Platinum | 250,000‡ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[120] | 2× Diamond | 2,000,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[121] | 2× Platinum | 600,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[122] | 3× Gold | 750,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[123] sales since 2009 |

Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[124] | Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[125] | Silver | 20,000[126] |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[127] reissue |

2× Platinum | 40,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[128] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| South Africa (RISA)[129] | Gold | 150,000[130] |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[131] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[132] | 6× Platinum | 1,800,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[133] | 24× Platinum | 24,000,000‡ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

Notes

- ^ While most commonly called Led Zeppelin IV, Atlantic Records catalogues have used the names Four Symbols and The Fourth Album; it has also been referred to as ZoSo (which Page's symbol appears to spell), Untitled, and Runes.[3]

- ^ Plant knew Denny via a mutual friend, Fairport bassist Dave Pegg. Pegg, Plant and Bonham had played together on the 1960s Birmingham club circuit in the group The Way of Life.[19]

- ^ Several sources have claimed that King's most critically and commercially successful album, Tapestry, kept Led Zeppelin IV from No. 1,[3] but the latter was still being mixed during the former's chart run over summer 1971.[48]

- ^ A biography of Memphis Minnie also lists Kansas Joe McCoy as a writer.[98]

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Led Zeppelin IV, Led Zeppelin, Atlantic Records, R2-536185, Super Deluxe Edition Box, 2014 Liner Notes, page 3

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 51, 89.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Lewis 1990, p. 51.

- ^ Reuters Staff (5 October 2020). "Led Zeppelin emerges victor in Stairway to Heaven plagiarism case". Reuters. reuters.com. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

(Reuters) - British rock band Led Zeppelin on Monday effectively won a long-running legal battle over claims it stole the opening guitar riff from its signature 1971 song "Stairway to Heaven."

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Royal Mail unveil classic album cover stamps". The Independent. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Royal Mail puts classic albums on to stamps". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2018). Led Zeppelin All The Songs. Co-written by Philippe Margotin. Running Press. ISBN 9780316418034.

- ^ "Their Time is Gonna Come". Classic Rock Magazine. December 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lewis 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis 1990, p. 16.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 91.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 89.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 16, 89.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Lewis 1990, p. 96.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Lewis 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis 2010, p. 76.

- ^ 33 1/3 book

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 89.

- ^ Shadwick 2005, p. 162.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 86.

- ^ "No Quarter". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Welch, Chris (31 October 2013). "Andy Johns on the secrets behind the Led Zeppelin IV sessions". MusicRadar. Future Publishing. Archived from the original on 4 November 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 84.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 93.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Schulps, Dave (October 1977). "Interview with Jimmy Page". Trouser Press. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- ^ Jackson, James (8 January 2010). "Jimmy Page on Led Zeppelin IV, the band's peak and their reunion". The Times. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- ^ Scaggs, Austin (5 May 2005). "Q&A: Robert Plant". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009.

- ^ Gettings, Fred (1981). The Dictionary of Occult, Hermetic, and Alchemical Sigils and Symbols. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. p. 201. ISBN 0-7100-0095-2. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Untitled (Media notes). Atlantic Records. 1972. K50008.

- ^ Lewis & Pallett 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Lewis 2010, p. 97.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tolinski, Brad; Di Benedetto, Greg (January 1998). "Light and Shade". Guitar World.

- ^ "How the Led Zeppelin IV album cover would look it was made today – 45 years on". Birmingham Mail. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2020. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Jackson, James (8 January 2010). "Jimmy Page on Led Zeppelin's good times, bad times and reunion rumours". The Times.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (8 January 2010). "Coldplay album gets stamp of approval from Royal Mail". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ "The 10 Wildest Led Zeppelin Legends, Fact-Checked". Rolling Stone. 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ Davis, Erik (2005). Led Zeppelin's Led Zeppelin IV. A&C Black. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-826-41658-2.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Lynch, John (9 August 2017). "The 50 best-selling albums of all time". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Top 200 Albums". Billboard. 18 December 1971. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Top 200 Albums". Billboard. 8 January 1972. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ "Billboard 200 : 1971". Billboard. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Larkin, Colin (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (29 July 2014). "Led Zeppelin IV: is this the greatest rock album ever made?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Albums". RIAA. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lewis 1990, p. 94.

- ^ "The Complete Studio Recordings". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Lewis 1990, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Led Zeppelin IV (Media notes). Atlantic Records. 1994. 7567-82638-2.

- ^ Bennett, Ross (29 July 2014). "Led Zeppelin IV and Houses of the Holy Remasters Due". Mojo. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Reviews for Led Zeppelin IV [Remastered] by Led Zeppelin". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin IV [Remastered] by Led Zeppelin Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "AllMusic Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 September 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin IV". Blender. Archived from the original on 26 September 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Christgau, Robert (13 October 1981). "Led Zeppelin IV". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. p. 222. ISBN 0-89919-025-1. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195313734.

- ^ Sinclair, Tom (20 June 2003). "On the Records ... Led Zeppelin". Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Snow, Mat (November 2014). "More muscle in your bustle: Led Zeppelin Led Zeppelin IV". Mojo. p. 106.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 662. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ Richardson, Mark (24 February 2015). "Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin IV/Houses of the Holy/Physical Graffiti". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Review: Led Zeppelin IV". Q. London: 141. October 1994.

- ^ Kot, Greg; et al. (2004). Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. p. 479. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ "Rolling Stone Review". Rolling Stone. 23 December 1971. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Album Reviews". Billboard. 20 November 1971. p. 70. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (3 March 1972). "Consumer Guide (24)". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (4 October 1976). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ^ Gross, Joe (February 2005). "Heavy Metal". Spin. 21 (2). Vibe/Spin Ventures: 89. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (2007). "Review of Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 12 January 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Dusting 'Em Off: Led Zeppelin IV". 7 June 2014. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (5 December 2011). "All That Glitters: Led Zeppelin – 'When the Levee Breaks'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Herrmann, Brenda (18 June 1991). "Ranking Rock, Enraging Fans". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Jones, Mablen (1987). Getting It On: The Clothing of Rock'n'Roll. Abbeville Press. p. 115. ISBN 0896596869.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (2018). Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic Rock. Dey Street. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780062657121. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- ^ "100 Greatest British Albums". Q. London. June 2000. p. 76.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (September 2002). "40 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time". Spin. p. 81. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 54. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Led Zeppelin IV ranked 58th greatest album by Rolling Stone magazine". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pitchfork Staff (23 June 2004). "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. p. 10. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin Albums Ranked From Worst To Best – The Ultimate Guide". loudersound. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Albums Ever Made — January 1996". Mojo. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "The Grammy Hall of Fame Award". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ "Album of the Millennium — December 1999". The Guitar. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Classic Rock – 100 Greatest Rock Albums Ever December 2001". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ Dimery, Robert (2011). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Hachette UK. p. 856. ISBN 978-1-844-03714-8.

- ^ "100 Greatest Albums Ever – February 2006". Q. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Classic Rock – 100 Greatest British Rock Albums Ever — April 2006". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "The Definitive 200: Top 200 Albums of All-Time". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (United States). Archived from the original on 22 January 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

- ^ "Rocklist.net....NME: The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time : October 2013". www.rocklistmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Untitled (a.k.a. Led Zeppelin IV) (Album notes). Led Zeppelin. New York City: Atlantic Records. 1971. LP labels. SD 7208.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Garon, Paul (2014). Woman with guitar : Memphis Minnie's blues (Revised and expanded ed.). San Francisco. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0872866218.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ramirez, AJ (31 October 2011). "All That Glitters: Led Zeppelin – The Battle of Evermore". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ "Top 20 Albums – 11 March 1972". Go-Set. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ "Discographie Led Zeppelin – austriancharts.at". austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "RPM Albums Chart – 8 January 1972". RPM. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ "LP Top 10 – November 22, 1971". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ "Extended Search: Led Zeppelin". dutchcharts.nl (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2006). Sisältää hitin – levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972 (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 978-951-1-21053-5.

- ^ "French Chart" (in French). infodisc. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ "Suche – Offizielle Deutsche Charts" (Enter "Led Zeppelin" in the search box). GfK Entertainment Charts. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "Extended Search: Led Zeppelin". norwegiancharts.com. Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "HITS ALLER TIJDEN". www.hitsallertijden.nl. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "CASH BOX MAGAZINE: Music and coin machine magazine 1942 to 1996". worldradiohistory.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "RECORD WORLD MAGAZINE: 1942 to 1982". worldradiohistory.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2014. 44. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. 1972. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Metal Albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on 12 August 2004. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin 4" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV". Music Canada.

- ^ "French album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Volume 4" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Led Zeppelin; 'Led Zeppelin IV')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 13 November 2019. Select "2018" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "Led Zeppelin IV" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "A platinum sales award foe the album 'Led Zeppelin IV'". 20 December 2020.

- ^ "WEA's International's..." (PDF). Cash Box. 16 September 1972. p. 42.

- ^ "Gold/Silver Record Chart". Billboard. 26 December 1974. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Norwegian album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Salaverrie, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. p. 956. ISBN 84-8048-639-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Lot #470 Led Zeppelin South African Record Award". Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Lot #470 Led Zeppelin South African Record Award".

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('4')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "British album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "American album certifications – Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin IV". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

Bibliography

- Lewis, Dave (1990). Led Zeppelin : A Celebration. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-2416-1.

- Lewis, Dave (2010). Led Zeppelin: The "Tight But Loose" Files. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-220-9.

- Lewis, Dave; Pallett, Simon (2007). Led Zeppelin: The Concert File. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-5307-9.

- Shadwick, Keith (2005). Led Zeppelin: The Story of a Band and Their Music, 1968–80. Backbeat. ISBN 978-0-87930-871-1.

External links

- Led Zeppelin IV at Discogs (list of releases)

- Led Zeppelin IV at MusicBrainz