Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea | |

|---|---|

6th century Syriac portrait of St. Eusebius of Caesarea from the Rabbula Gospels | |

| Born | c. 260–265 Caesarea Maritima |

| Died | 30 May 339[1] |

| Occupation | Bishop, historian, theologian |

| Period | Constantinian dynasty |

| Notable works | Ecclesiastical History, On the Life of Pamphilus, Chronicle, On the Martyrs |

Eusebius of Caesarea | |

|---|---|

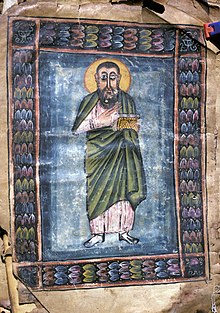

Icon portrait of the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea as a saint from T'oros Roslin Gospel manuscript in Armenia dated 1262 | |

| The Father of Church History | |

| Venerated in | Syriac Orthodox Church [2] |

| Feast | May 30 (ancient Syrian Church)[3] February 29 (Syrian Orthodox) [4] June 21 (Roman Catholic; Suppressed by Pope Gregory XIII)[5][6] |

| Influences | Origen, St. Pamphilus of Caesarea, St. Constantine the Great, Sextus Julius Africanus, Philo, Plato |

| Influenced | St. Palladius of Galatia, St. Basil the Great, Rufinus of Aquileia, St. Theodoret of Cyrus, Socrates of Constantinople, Sozomen, Evagrius Scholasticus, Gelasius of Cyzicus, Michael the Syrian, St. Jerome, Philostorgius, Victorius of Aquitaine, Pope St. Gelasius I, Pope Pelagius II, Henri Valois, George Bull, William Cave, Samuel Lee, J.B. Lightfoot, Henry Wace |

Eusebius of Caesarea (/juːˈsiːbiəs/; Template:Lang-grc-gre Eusebios; c. 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus[7] (from the Template:Lang-grc-gre), was a Greek[8] historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima in the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. Together with Pamphilus, he was a scholar of the biblical canon and is regarded as one of the most learned Christians during late antiquity.[9] He wrote Demonstrations of the Gospel, Preparations for the Gospel and On Discrepancies between the Gospels, studies of the biblical text. As "Father of Church History"[note 1] (not to be confused with the title of Church Father), he produced the Ecclesiastical History, On the Life of Pamphilus, the Chronicle and On the Martyrs. He also produced a biographical work on Constantine the Great, the first Christian Roman emperor, who was augustus between AD 306 and AD 337.

Although Eusebius' works are regarded as giving insight into the history of the early church, he was not without prejudice, especially in regard to the Jews, for while "Eusebius indeed blames the Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus, he nevertheless also states that forgiveness can be granted even for this sin and that the Jews can receive salvation."[11] Some scholars question the accuracy of Eusebius' works. For example, at least one scholar, Lynn Cohick, dissents from the majority view that Eusebius is correct in identifying the Melito of Peri Pascha with the Quartodeciman bishop of Sardis. Cohick claims as support for her position that "Eusebius is a notoriously unreliable historian, and so anything he reports should be critically scrutinized."[12] Eusebius' Life of Constantine, which he wrote as a eulogy shortly after the emperor's death in AD 337, is "often maligned for perceived factual errors, deemed by some so hopelessly flawed that it cannot be the work of Eusebius at all."[13] Others attribute this perceived flaw in this particular work as an effort at creating an overly idealistic hagiography, calling him a "Constantinian flunky"[14] since, as a trusted adviser to Constantine, it would be politically expedient for him to present Constantine in the best light possible.

Sources

Little is known about the life of Eusebius. His successor at the See of Caesarea, Acacius, wrote a Life of Eusebius, a work that has since been lost. Eusebius' own surviving works probably only represent a small portion of his total output. Beyond notices in his extant writings, the major sources are the 5th-century ecclesiastical historians Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret, and the 4th-century Christian author Jerome. There are assorted notices of his activities in the writings of his contemporaries Athanasius, Arius, Eusebius of Nicomedia, and Alexander of Alexandria. Eusebius' pupil, Eusebius of Emesa, provides some incidental information.[15]

Early life

Most scholars date the birth of Eusebius to some point between AD 260 and 265.[9][16] He was most likely born in or around Caesarea Maritima.[9][17] Nothing is known about his parents.[18] He was baptized and instructed in the city, and lived in Syria Palaestina in 296, when Diocletian's army passed through the region (in the Life of Constantine, Eusebius recalls seeing Constantine traveling with the army).[19][20]

Eusebius was made presbyter by Agapius of Caesarea.[19] Some, like theologian and ecclesiastical historian John Henry Newman, understand Eusebius' statement that he had heard Dorotheus of Tyre "expound the Scriptures wisely in the Church" to indicate that Eusebius was Dorotheus' pupil while the priest was resident in Antioch; others, like the scholar D. S. Wallace-Hadrill, deem the phrase too ambiguous to support the contention.[21]

Through the activities of the theologian Origen (185/6–254) and the school of his follower Pamphilus (later 3rd century – 309), Caesarea became a center of Christian learning. Origen was largely responsible for the collection of usage information, or which churches were using which gospels, regarding the texts which became the New Testament. The information used to create the late-fourth-century Easter Letter, which declared accepted Christian writings, was probably based on the Ecclesiastical History [HE] of Eusebius of Caesarea, wherein he uses the information passed on to him by Origen to create both his list at HE 3:25 and Origen's list at HE 6:25. Eusebius got his information about what texts were accepted by the third-century churches throughout the known world, a great deal of which Origen knew of firsthand from his extensive travels, from the library and writings of Origen.[22]

On his deathbed, Origen had made a bequest of his private library to the Christian community in the city.[23] Together with the books of his patron Ambrosius, Origen's library (including the original manuscripts of his works[24][note 2]) formed the core of the collection that Pamphilus established.[26] Pamphilus also managed a school that was similar to (or perhaps a re-establishment of[27]) that of Origen.[28] Pamphilus was compared to Demetrius of Phalerum and Pisistratus, for he had gathered Bibles "from all parts of the world".[29] Like his model Origen, Pamphilus maintained close contact with his students. Eusebius, in his history of the persecutions, alludes to the fact that many of the Caesarean martyrs lived together, presumably under Pamphilus.[30]

Soon after Pamphilus settled in Caesarea (ca. 280s), he began teaching Eusebius, who was then somewhere between twenty and twenty-five.[31] Because of his close relationship with his schoolmaster, Eusebius was sometimes called Eusebius Pamphili: "Eusebius, son of Pamphilus".[note 3] The name may also indicate that Eusebius was made Pamphilus' heir.[34] Pamphilus gave Eusebius a strong admiration for the thought of Origen.[35] Neither Pamphilus nor Eusebius knew Origen personally;[36] Pamphilus probably picked up Origenist ideas during his studies under Pierius (nicknamed "Origen Junior"[37]) in Alexandria.[38]

Eusebius' Preparation for the Gospel bears witness to the literary tastes of Origen: Eusebius quotes no comedy, tragedy, or lyric poetry, but makes reference to all the works of Plato and to an extensive range of later philosophic works, largely from Middle Platonists from Philo to the late 2nd century.[39] Whatever its secular contents, the primary aim of Origen and Pamphilus' school was to promote sacred learning. The library's biblical and theological contents were more impressive: Origen's Hexapla and Tetrapla; a copy of the original Aramaic version of the Gospel of Matthew; and many of Origen's own writings.[31] Marginal comments in extant manuscripts note that Pamphilus and his friends and pupils, including Eusebius, corrected and revised much of the biblical text in their library.[31] Their efforts made the hexaplaric Septuagint text increasingly popular in Syria and Palestine.[40] Soon after joining Pamphilus' school, Eusebius started helping his master expand the library's collections and broaden access to its resources. At about this time Eusebius compiled a Collection of Ancient Martyrdoms, presumably for use as a general reference tool.[31]

In the 290s, Eusebius began work on his most important work, the Ecclesiastical History, a narrative history of the Church and Christian community from the Apostolic Age to Eusebius' own time. At about the same time, he worked on his Chronicle, a universal calendar of events from the Creation to, again, Eusebius' own time. He completed the first editions of the Ecclesiastical History and Chronicle before 300.[41]

Bishop of Caesarea

Eusebius succeeded Agapius as Bishop of Caesarea soon after 313 and was called on by Arius who had been excommunicated by his bishop Alexander of Alexandria. An episcopal council in Caesarea pronounced Arius blameless.[42] Eusebius enjoyed the favor of the Emperor Constantine. Because of this he was called upon to present the creed of his own church to the 318 attendees of the Council of Nicaea in 325.[43] However, the anti-Arian creed from Palestine prevailed, becoming the basis for the Nicene Creed.[44]

The theological views of Arius, that taught the subordination of the Son to the Father, continued to be controversial. Eustathius of Antioch strongly opposed the growing influence of Origen's theology as the root of Arianism. Eusebius, an admirer of Origen, was reproached by Eustathius for deviating from the Nicene faith. Eusebius prevailed and Eustathius was deposed at a synod in Antioch.[citation needed]

However, Athanasius of Alexandria became a more powerful opponent and in 334 he was summoned before a synod in Caesarea (which he refused to attend). In the following year, he was again summoned before a synod in Tyre at which Eusebius of Caesarea presided. Athanasius, foreseeing the result, went to Constantinople to bring his cause before the Emperor. Constantine called the bishops to his court, among them Eusebius. Athanasius was condemned and exiled at the end of 335. Eusebius remained in the Emperor's favour throughout this time and more than once was exonerated with the explicit approval of the Emperor Constantine.[citation needed] After the Emperor's death (c. 337), Eusebius wrote the Life of Constantine, an important historical work because of eyewitness accounts and the use of primary sources.[45]

Works

Of the extensive literary activity of Eusebius, a relatively large portion has been preserved. Although posterity suspected him of Arianism, Eusebius had made himself indispensable by his method of authorship; his comprehensive and careful excerpts from original sources saved his successors the painstaking labor of original research. Hence, much has been preserved, quoted by Eusebius, which otherwise would have been lost.

The literary productions of Eusebius reflect on the whole the course of his life. At first, he occupied himself with works on biblical criticism under the influence of Pamphilus and probably of Dorotheus of Tyre of the School of Antioch. Afterward, the persecutions under Diocletian and Galerius directed his attention to the martyrs of his own time and the past, and this led him to the history of the whole Church and finally to the history of the world, which, to him, was only a preparation for ecclesiastical history.

Then followed the time of the Arian controversies, and dogmatic questions came into the foreground. Christianity at last found recognition by the State; and this brought new problems – apologies of a different sort had to be prepared. Lastly, Eusebius wrote eulogies in praise of Constantine. To all this activity must be added numerous writings of a miscellaneous nature, addresses, letters, and the like, and exegetical works that extended over the whole of his life and that include both commentaries and an important treatise on the location of biblical place names and the distances between these cities.

Onomasticon

Biblical text criticism

Pamphilus and Eusebius occupied themselves with the textual criticism of the Septuagint text of the Old Testament and especially of the New Testament. An edition of the Septuagint seems to have been already prepared by Origen, which, according to Jerome, was revised and circulated by Eusebius and Pamphilus. For an easier survey of the material of the four Evangelists, Eusebius divided his edition of the New Testament into paragraphs and provided it with a synoptical table so that it might be easier to find the pericopes that belong together. These canon tables or "Eusebian canons" remained in use throughout the Middle Ages, and illuminated manuscript versions are important for the study of early medieval art, as they are the most elaborately decorated pages of many Gospel books. Eusebius detailed in Epistula ad Carpianum how to use his canons.

Chronicle

The Chronicle (Παντοδαπὴ Ἱστορία (Pantodape historia)) is divided into two parts. The first part, the Chronography (Χρονογραφία (Chronographia)), gives an epitome of universal history from the sources, arranged according to nations. The second part, the Canons (Χρονικοὶ Κανόνες (Chronikoi kanones)), furnishes a synchronism of the historical material in parallel columns, the equivalent of a parallel timeline.[46]

The work as a whole has been lost in the original Greek, but it may be reconstructed from later chronographists of the Byzantine school who made excerpts from the work, especially George Syncellus. The tables of the second part have been completely preserved in a Latin translation by Jerome, and both parts are still extant in an Armenian translation. The loss of the Greek originals has given the Armenian translation a special importance; thus, the first part of Eusebius' Chronicle, of which only a few fragments exist in Greek, has been preserved entirely in Armenian, though with lacunae. The Chronicle as preserved extends to the year 325.[47]

Church History

In his Church History or Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius wrote the first surviving history of the Christian Church as a chronologically ordered account, based on earlier sources, complete from the period of the Apostles to his own epoch.[48] The time scheme correlated the history with the reigns of the Roman Emperors, and the scope was broad. Included were the bishops and other teachers of the Church, Christian relations with the Jews and those deemed heretical, and the Christian martyrs through 324.[49] Although its accuracy and biases have been questioned,[50] it remains an important source on the early church due to Eusebius's access to materials now lost.[51]

Life of Constantine

Eusebius' Life of Constantine (Vita Constantini) is a eulogy or panegyric, and therefore its style and selection of facts are affected by its purpose, rendering it inadequate as a continuation of the Church History. As the historian Socrates Scholasticus said, at the opening of his history which was designed as a continuation of Eusebius, "Also in writing the life of Constantine, this same author has but slightly treated of matters regarding Arius, being more intent on the rhetorical finish of his composition and the praises of the emperor than on an accurate statement of facts." The work was unfinished at Eusebius' death. Some scholars have questioned the Eusebian authorship of this work. [who?]

Conversion of Constantine according to Eusebius

Writing decades after Constantine had died, Eusebius claimed that the emperor himself had recounted to him that some time between the death of his father – the augustus Constantius – and his final battle against his rival Maxentius as augustus in the West, Constantine experienced a vision in which he and his soldiers beheld a Christian symbol, "a cross-shaped trophy formed from light", above the sun at midday.[52][53] Attached to the symbol was the phrase "by this conquer" (Template:Lang-grc), a phrase often rendered into Latin as "in hoc signo vinces".[52] In a dream that night "the Christ of God appeared to him with the sign which had appeared in the sky, and urged him to make himself a copy of the sign which had appeared in the sky, and to use this as a protection against the attacks of the enemy."[53] Eusebius relates that this happened "on a campaign he [Constantine] was conducting somewhere".[53][52] It is unclear from Eusebius's description whether the shields were marked with a Christian cross or with a chi-rho, a staurogram, or another similar symbol.[52]

The Latin text De mortibus persecutorum contains an early account of the 28 October 312 Battle of the Milvian Bridge written by Lactantius probably in 313, the year following the battle. Lactantius does not mention a vision in the sky but describes a revelatory dream on the eve of battle.[54] Eusebius's work of that time, his Church History, also makes no mention of the vision.[52] The Arch of Constantine, constructed in AD 315, neither depicts a vision nor any Christian insignia in its depiction of the battle. In his posthumous biography of Constantine, Eusebius agrees with Lactantius that Constantine received instructions in a dream to apply a Christian symbol as a device to his soldiers' shields, but unlike Lactantius and subsequent Christian tradition, Eusebius does not date the events to October 312 and does not connect Constantine's vision and dream-vision with the Battle of the Milvian Bridge.[52]

Minor historical works

Before he compiled his church history, Eusebius edited a collection of martyrdoms of the earlier period and a biography of Pamphilus. The martyrology has not survived as a whole, but it has been preserved almost completely in parts. It contained:

- an epistle of the congregation of Smyrna concerning the martyrdom of Polycarp;

- the martyrdom of Pionius;

- the martyrdoms of Carpus, Papylus, and Agathonike;

- the martyrdoms in the congregations of Vienne and Lyon;

- the martyrdom of Apollonius.

Of the life of Pamphilus, only a fragment survives. A work on the martyrs of Palestine in the time of Diocletian was composed after 311; numerous fragments are scattered in legendaries which have yet to be collected. The life of Constantine was compiled after the death of the emperor and the election of his sons as Augusti (337). It is more a rhetorical eulogy on the emperor than a history but is of great value on account of numerous documents incorporated into it.

Apologetic and dogmatic works

To the class of apologetic and dogmatic works belong:

- The Apology for Origen, the first five books of which, according to the definite statement of Photius, were written by Pamphilus in prison, with the assistance of Eusebius. Eusebius added the sixth book after the death of Pamphilus. We possess only a Latin translation of the first book, made by Rufinus.

- A treatise against Hierocles (a Roman governor), in which Eusebius combated the former's glorification of Apollonius of Tyana in a work entitled A Truth-loving Discourse (Greek: Philalethes logos); in spite of manuscript attribution to Eusebius, however, it has been argued (by Thomas Hagg[55] and more recently, Aaron Johnson)[56] that this treatise "Against Hierocles" was written by someone other than Eusebius of Caesarea.

- Praeparatio evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel), commonly known by its Latin title, which attempts to prove the excellence of Christianity over every pagan religion and philosophy. The Praeparatio consists of fifteen books which have been completely preserved. Eusebius considered it an introduction to Christianity for pagans. But its value for many later readers is more because Eusebius studded this work with so many lively fragments from historians and philosophers which are nowhere else preserved. Here alone is preserved Pyrrho's translation of the Buddhist Three marks of existence upon which Pyrrho based Pyrrhonism. Here alone is a summary of the writings of the Phoenician priest Sanchuniathon of which the accuracy has been shown by the mythological accounts found on the Ugaritic tables. Here alone is the account from Diodorus Siculus's sixth book of Euhemerus' wondrous voyage to the island of Panchaea where Euhemerus purports to have found his true history of the gods. And here almost alone is preserved writings of the neo-Platonist philosopher Atticus along with so much else.

- Demonstratio evangelica (Proof of the Gospel) is closely connected to the Praeparatio and comprised originally twenty books of which ten have been completely preserved as well as a fragment of the fifteenth. Here Eusebius treats of the person of Jesus Christ. The work was probably finished before 311;

- Another work which originated in the time of the persecution, entitled Prophetic Extracts (Eclogae propheticae). It discusses in four books the Messianic texts of Scripture. The work is merely the surviving portion (books 6–9) of the General elementary introduction to the Christian faith, now lost. The fragments given as the Commentary on Luke in the PG have been claimed to derive from the missing tenth book of the General Elementary Introduction (see D. S. Wallace-Hadrill); however, Aaron Johnson has argued that they cannot be associated with this work.[57]

- The treatise On Divine Manifestation or On the Theophania (Peri theophaneias), of unknown date. It treats of the incarnation of the Divine Logos, and its contents are in many cases identical with the Demonstratio evangelica. Only fragments are preserved in Greek, but a complete Syriac translation of the Theophania survives in an early 5th-century manuscript. Samuel Lee, the editor (1842) and translator (1843) of the Syriac Theophania, thought that the work must have been written "after the general peace restored to the Church by Constantine, and before either the 'Praeparatio,' or the 'Demonstratio Evangelica,' was written ...It appears probable ... therefore, that this was one of the first productions of Eusebius, if not the first after the persecutions ceased."[58] Hugo Gressmann, noting in 1904 that the Demonstratio seems to be mentioned at IV. 37 and V. 1, and that II. 14 seems to mention the extant practice of temple prostitution at Hieropolis in Phoenica, concluded that the Theophania was probably written shortly after 324. Others have suggested a date as late as 337.[59]

- A polemical treatise against Marcellus of Ancyra, the Against Marcellus, dating from about 337;

- A supplement to the last-named work, also against Marcellus, entitled Ecclesiastical Theology, in which he defended the Nicene doctrine of the Logos against the party of Athanasius.

A number of writings, belonging in this category, have been entirely lost.

Exegetical and miscellaneous works

All of the exegetical works of Eusebius have suffered damage in transmission. The majority of them are known to us only from long portions quoted in Byzantine catena-commentaries. However these portions are very extensive. Extant are:

- An enormous Commentary on the Psalms;

- A commentary on Isaiah, discovered more or less complete in a manuscript in Florence early in the 20th century and published 50 years later;

- Small fragments of commentaries on Romans and 1 Corinthians.

Eusebius also wrote a work Quaestiones ad Stephanum et Marinum, On the Differences of the Gospels (including solutions). This was written for the purpose of harmonizing the contradictions in the reports of the different Evangelists. This work was recently (2011) translated into the English language by David J. Miller and Adam C. McCollum and was published under the name Eusebius of Caesarea: Gospel Problems and Solutions.[60] The original work was also translated into Syriac, and lengthy quotations exist in a catena in that language, and also in Arabic catenas.[61]

Eusebius also wrote treatises on the biblical past; these three treatises have been lost. They were:

- A work on the Greek equivalents of Hebrew Gentilic nouns;

- A description of old Judea with an account of the loss of the ten tribes;

- A plan of Jerusalem and the Temple of Solomon.

The addresses and sermons of Eusebius are mostly lost, but some have been preserved, e.g., a sermon on the consecration of the church in Tyre and an address on the thirtieth anniversary of the reign of Constantine (336).

Most of Eusebius' letters are lost. His letters to Carpianus and Flacillus exist complete. Fragments of a letter to the empress Constantia also exists.

Doctrine

This section possibly contains original research. (December 2019) |

Eusebius is fairly unusual in his preterist, or fulfilled, eschatological view. Saying "the Holy Scriptures foretell that there will be unmistakable signs of the Coming of Christ. Now there were among the Hebrews three outstanding offices of dignity, which made the nation famous, firstly the kingship, secondly that of prophet, and lastly the high priesthood. The prophecies said that the abolition and complete destruction of all these three together would be the sign of the presence of the Christ. And that the proofs that the times had come, would lie in the ceasing of the Mosaic worship, the desolation of Jerusalem and its Temple, and the subjection of the whole Jewish race to its enemies. ...The holy oracles foretold that all these changes, which had not been made in the days of the prophets of old, would take place at the coming of the Christ, which I will presently shew to have been fulfilled as never before in accordance with the predictions" (Demonstratio Evangelica VIII).

From a dogmatic point of view, Eusebius stands entirely upon the shoulders of Origen. Like Origen, he started from the fundamental thought of the absolute sovereignty (monarchia) of God. God is the cause of all beings. But he is not merely a cause; in him everything good is included, from him all life originates, and he is the source of all virtue. God sent Christ into the world that it may partake of the blessings included in the essence of God. Eusebius expressly distinguishes the Son as distinct from Father as a ray is also distinct from its source the sun.[citation needed]

Eusebius held that men were sinners by their own free choice and not by the necessity of their natures. Eusebius said:

The Creator of all things has impressed a natural law upon the soul of every man, as an assistant and ally in his conduct, pointing out to him the right way by this law; but, by the free liberty with which he is endowed, making the choice of what is best worthy of praise and acceptance, he has acted rightly, not by force, but from his own free-will, when he had it in his power to act otherwise, As, again, making him who chooses what is worst, deserving of blame and punishment, because he has by his own motion neglected the natural law, and becoming the origin and fountain of wickedness, and misusing himself, not from any extraneous necessity, but from free will and judgment. The fault is in him who chooses, not in God. For God has not made nature or the substance of the soul bad; for he who is good can make nothing but what is good. Everything is good which is according to nature. Every rational soul has naturally a good free-will, formed for the choice of what is good. But when a man acts wrongly, nature is not to be blamed; for what is wrong, takes place not according to nature, but contrary to nature, it being the work of choice, and not of nature.[62]

A letter Eusebius is supposed to have written to Constantine's daughter Constantina, refusing to fulfill her request for images of Christ, was quoted in the decrees (now lost) of the Iconoclast Council of Hieria in 754, and later quoted in part in the rebuttal of the Hieria decrees in the Second Council of Nicaea of 787, now the only source from which some of the text is known. The authenticity or authorship of the letter remains uncertain.[63]

Nicene Creed

In the June 2002 issue of the Church History journal, Pier Beatrice reports that Eusebius testified that the word homoousios (consubstantial) "was inserted in the Nicene Creed solely by the personal order of Constantine."[64]

According to Eusebius of Caesarea, the word homoousios was inserted in the Nicene Creed solely by the personal order of Constantine. But this statement is highly problematic. It is very difficult to explain the seeming paradoxical fact that this word, along with the explanation given by Constantine, was accepted by the "Arian" Eusebius, whereas it has left no traces at all in the works of his opponents, the leaders of the anti-Arian party such as Alexander of Alexandria, Ossius of Cordova, Marcellus of Ancyra, and Eustathius of Antioch, who are usually considered Constantine's theological advisers and the strongest supporters of the council. Neither before nor during Constantine's time is there any evidence of a normal, well-established Christian use of the term homoousios in its strictly Trinitarian meaning. Having once excluded any relationship of the Nicene homoousios with the Christian tradition, it becomes legitimate to propose a new explanation, based on an analysis of two pagan documents which have so far never been taken into account. The main thesis of this paper is that homoousios came straight from Constantine's Hermetic background. As can be clearly seen in the Poimandres, and even more clearly in an inscription mentioned exclusively in the Theosophia, in the theological language of Egyptian paganism the word homoousios meant that the Nous-Father and the Logos-Son, who are two distinct beings, share the same perfection of the divine nature.

— Pier Franco Beatrice, "The Word 'Homoousios' from Hellenism to Christianity", Church History, Volume 71, № 2, June 2002, p. 243

Assessment

- Socrates Scholasticus (a 5th-century Christian historian), writing in his own Church History, criticized the Life of Constantine, stating that Eusebius was "more intent on the rhetorical finish of his composition and the praises of the emperor, than on an accurate statement of facts".[65]

- Edward Gibbon openly distrusted the writings of Eusebius concerning the number of martyrs, by noting a passage in the shorter text of the Martyrs of Palestine attached to the Ecclesiastical History (Book 8, Chapter 2) in which Eusebius introduces his description of the martyrs of the Great Persecution under Diocletian with: "Wherefore we have decided to relate nothing concerning them except the things in which we can vindicate the Divine judgment. ...We shall introduce into this history in general only those events which may be useful first to ourselves and afterwards to posterity." In the longer text of the same work, chapter 12, Eusebius states: "I think it best to pass by all the other events which occurred in the meantime: such as ... the lust of power on the part of many, the disorderly and unlawful ordinations, and the schisms among the confessors themselves; also the novelties which were zealously devised against the remnants of the Church by the new and factious members, who added innovation after innovation and forced them in unsparingly among the calamities of the persecution, heaping misfortune upon misfortune. I judge it more suitable to shun and avoid the account of these things, as I said at the beginning."

- When his own honesty was challenged by his contemporaries,[66] Gibbon appealed to a chapter heading in Eusebius' Praeparatio evangelica (Book XII, Chapter 31)[67] in which Eusebius discussed "that it will be necessary sometimes to use falsehood as a remedy for the benefit of those who require such a mode of treatment."[68]

- Although Gibbon refers to Eusebius as the "gravest" of the ecclesiastical historians,[69] he also suggests that Eusebius was more concerned with the passing political concerns of his time than with his duty as a reliable historian.[70]

- Jacob Burckhardt (19th century cultural historian) dismissed Eusebius as "the first thoroughly dishonest historian of antiquity".

- Other critics of Eusebius' work cite the panegyrical tone of the Vita, plus the omission of internal Christian conflicts in the Canones, as reasons to interpret his writing with caution.[71]

Alternate views have suggested that Gibbon's dismissal of Eusebius is inappropriate:

- With reference to Gibbon's comments, Joseph Barber Lightfoot (late 19th century theologian and former Bishop of Durham) pointed out[72] that Eusebius' statements indicate his honesty in stating what he was not going to discuss, and also his limitations as a historian in not including such material. He also discusses the question of accuracy. "The manner in which Eusebius deals with his very numerous quotations elsewhere, where we can test his honesty, is a sufficient vindication against this unjust charge." Lightfoot also notes that Eusebius cannot always be relied on: "A far more serious drawback to his value as a historian is the loose and uncritical spirit in which he sometimes deals with his materials. This shows itself in diverse ways. He is not always to be trusted in his discrimination of genuine and spurious documents."

- Averil Cameron (professor at King's College London and Oxford) and Stuart Hall (historian and theologian), in their recent translation of the Life of Constantine, point out that writers such as Burckhardt found it necessary to attack Eusebius in order to undermine the ideological legitimacy of the Habsburg empire, which based itself on the idea of Christian empire derived from Constantine, and that the most controversial letter in the Life has since been found among the papyri of Egypt.[73]

- In Church History (Vol. 59, 1990), Michael J. Hollerich (assistant professor at the Jesuit Santa Clara University, California) replies to Burckhardt's criticism of Eusebius, that "Eusebius has been an inviting target for students of the Constantinian era. At one time or another they have characterized him as a political propagandist, a good courtier, the shrewd and worldly adviser of the Emperor Constantine, the great publicist of the first Christian emperor, the first in a long succession of ecclesiastical politicians, the herald of Byzantinism, a political theologian, a political metaphysician, and a caesaropapist. It is obvious that these are not, in the main, neutral descriptions. Much traditional scholarship, sometimes with barely suppressed disdain, has regarded Eusebius as one who risked his orthodoxy and perhaps his character because of his zeal for the Constantinian establishment." Hollerich concludes that "the standard assessment has exaggerated the importance of political themes and political motives in Eusebius's life and writings and has failed to do justice to him as a churchman and a scholar".

While many have shared Burckhardt's assessment, particularly with reference to the Life of Constantine, others, while not pretending to extol his merits, have acknowledged the irreplaceable value of his works which may principally reside in the copious quotations that they contain from other sources, often lost.

Bibliography

- Eusebius of Caesarea.

- Historia Ecclesiastica (Church History) first seven books ca. 300, eighth and ninth book ca. 313, tenth book ca. 315, epilogue ca. 325.

- Migne, J.P., ed. Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta (in Greek). Patrologia Graeca 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online at Khazar Skeptik Archived 2009-12-28 at the Wayback Machine and Documenta Catholica Omnia. Accessed 4 November 2009.

- McGiffert, Arthur Cushman, trans. Church History. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent and CCEL. Accessed 28 September 2009.

- Williamson, G.A., trans. Church History. London: Penguin, 1989.

- Contra Hieroclem (Against Hierocles).

- Onomasticon (On the Place-Names in Holy Scripture).

- Klostermann, E., ed. Eusebius' Werke 3.1 (Die griechischen christlichen Schrifsteller der ersten (drei) Jahrhunderte 11.1. Leipzig and Berlin, 1904). Online at the Internet Archive. Accessed 29 January 2010.

- Wolf, Umhau, trans. The Onomasticon of Eusebius Pamphili: Compared with the version of Jerome and annotated. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1971. Online at Tertullian. Accessed 29 January 2010.

- Taylor, Joan E., ed. Palestine in the Fourth Century. The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea, translated by Greville Freeman-Grenville, and indexed by Rupert Chapman III (Jerusalem: Carta, 2003).

- De Martyribus Palestinae (On the Martyrs of Palestine).

- McGiffert, Arthur Cushman, trans. Martyrs of Palestine. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent and CCEL. Accessed June 9, 2009.

- Cureton, William, trans. History of the Martyrs in Palestine by Eusebius of Caesarea, Discovered in a Very Antient Syriac Manuscript. London: Williams & Norgate, 1861. Online at Tertullian. Accessed September 28, 2009.

- Praeparatio Evangelica (Preparation for the Gospel).

- Demonstratio Evangelica (Demonstration of the Gospel).

- Theophania (Theophany).

- Laudes Constantini (In Praise of Constantine) 335.

- Migne, J.P., ed. Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta (in Greek). Patrologia Graeca 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online at Khazar Skeptik Archived 2009-12-28 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 4 November 2009.

- Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. Oration in Praise of Constantine. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent. Accessed 19 October 2009.

- Vita Constantini (The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine) ca. 336–39.

- Migne, J.P., ed. Eusebiou tou Pamphilou, episkopou tes en Palaistine Kaisareias ta euriskomena panta (in Greek). Patrologia Graeca 19–24. Paris, 1857. Online at Khazar Skeptik Archived 2009-12-28 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 4 November 2009.

- Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. Life of Constantine. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 1. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent. Accessed 9 June 2009.

- Cameron, Averil and Stuart Hall, trans. Life of Constantine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Gregory Thaumaturgus. Oratio Panegyrica.

- Salmond, S.D.F., trans. From Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. 6. Edited by Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1886. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent. Accessed 31 January 2010.

- Jerome.

- Chronicon (Chronicle) ca. 380.

- Fotheringham, John Knight, ed. The Bodleian Manuscript of Jerome's Version of the Chronicle of Eusebius. Oxford: Clarendon, 1905. Online at the Internet Archive. Accessed 8 October 2009.

- Pearse, Roger, et al., trans. The Chronicle of St. Jerome, in Early Church Fathers: Additional Texts. Tertullian, 2005. Online at Tertullian. Accessed 14 August 2009.

- de Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men) 392.

- Herding, W., ed. De Viris Illustribus (in Latin). Leipzig: Teubner, 1879. Online at Internet Archive. Accessed 6 October 2009.

- Liber de viris inlustribus (in Latin). Texte und Untersuchungen 14. Leipzig, 1896.

- Richardson, Ernest Cushing, trans. De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men). From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 3. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent. Accessed 15 August 2009.

- Epistulae (Letters).

- Fremantle, W.H., G. Lewis and W.G. Martley, trans. Letters. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 6. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1893. Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Online at New Advent and CCEL. Accessed 19 October 2009.

- Origen.

- De Principiis (On First Principles).

See also

- Church Fathers

- Constantine I and Christianity

- Early Christianity

- Fifty Bibles of Constantine

- 4th century in Lebanon

- Travelogues of Palestine

Notes

- ^ Eusebius is considered the first historian of Christianity.[10]

- ^ Pamphilus might not have obtained all of Origen's writings, however: the library's text of Origen's commentary on Isaiah broke off at 30:6, while the original commentary was said to have taken up thirty volumes.[25]

- ^ There are three interpretations of this term: (1) that Eusebius was the "spiritual son", or favored pupil, of Pamphilus;[32] (2) that Eusebius was literally adopted by Pamphilus;[31] and (3) that Eusebius was Pamphilus' biological son. The third explanation is the least popular among scholars. The scholion on the Preparation for the Gospels 1.3 in the Codex Paris. 451 is usually adduced in support of the thesis. Most reject the scholion as too late or misinformed, but E. H. Gifford, an editor and translator of the Preparation, believes it to have been written by Arethas, the tenth-century archbishop of Caesarea, who was in a position to know the truth of the matter.[33]

References

Citations

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, pp. 94, 278

- ^ "The Church Historian and Metropolitan of Caesarea for twenty five years is included, on the list, among the Syrian martyrs and those who vouched for true faith (Wace & Piercy, 1999)." from Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan's 'Martyrs, Saints, and Prelates of the Syriac Orthodox Church Volume 2 published in 2012 on his website: http://rajanachen.com/download-english-books/

- ^ Shown in the Martyrology of 411 translated by William Wright in 1866 where it states under May 30, "The Commemoration of Eusebius, bishop of Palestine" (p. 427) which Wright confirms in the preface is "Eusebius of Caesareia" (p. 45). https://archive.org/details/WrightAnAncientSyrianMartyrology/page/n1/mode/2up

- ^ "His memory is celebrated on 29 February." from Cor-Episcopo K. Mani Rajan's 'Martyrs, Saints, and Prelates of the Syriac Orthodox Church Volume 2' published in 2012 on his website: http://rajanachen.com/download-english-books/

- ^ Bishop J.B. Lightfoot writes in his entry for St. Eusebius in Henry Wace's Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century AD, with an Account of Principal Sects and Heresies (1911) that while “in the Martyrologium Romanum itself he held his place for centuries,” in “the revision of this Martyrology under Gregory XIII his name was struck out, and Eusebius of Samosata was substituted, under the mistaken idea that Caesarea had been substituted for Samosata by a mistake.” (p. 536)

- ^ Multiple references for this day as the feast of St. Eusebius in multiple Roman Catholic martyrologies and lectionaries, as recorded by Henri Valois, or Valesius in his Testimonies of the Ancients in Favor of Eusebius and translated by Phillip Schaff https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf201.iii.iv.html

- ^ Eusebius (1876), Church History, Life of Constantine the Great, and Oration in Praise of Constantine, A Select Library of the Christian Church: Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 2nd ser., vol. I, translated by Schaff, Philip, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- ^ Jacobsen, Anders-Christian (2007). Three Greek apologists Origen, Eusebius, and Athanasius = Drei griechische Apologeten. Ulrich, Jörg. Frankfurt, M. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-631-56833-0. OCLC 180106520.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Gonzalez, Justo L. (2010-08-10). The Story of Christianity: Volume 1: The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. Zondervan. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-0-06-185588-7.

- ^ "General Audience of 13 June 2007: Eusebius of Caesarea | BENEDICT XVI". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2021-06-01.

- ^ Pamphili, Eusebius (2013). Elowsky (ed.). Commentary on Isaiah. Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic. pp. xxxii. ISBN 9780830829132.

- ^ Lang, T.J. (2015). Mystery and the Making of a Christian Historical Consciousness. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-11-044267-0.

- ^ Ferguson, Thomas C. (2005). The Past is Prologue: The Revolution of Nicene Historiography. Leiden/Boston: Brill. pp. 10. ISBN 90-04-14457-9.

- ^ Ferguson (15 June 2005). The Past is Prologue: The Revolution of Nicene Historiography. p. 49. ISBN 9789047407836.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill, 11.

- ^ Barnes, Timothy David (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Harvard University Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-674-16531-1.

Between 260-265 birth of Eusebius

- ^ Louth, "Birth of church history", 266; Quasten, 3.309.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Eusebius of Caesarea". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- ^ a b Wallace-Hadrill, 12, citing Socrates, Historia Ecclesiastica 1.8; Theodoret, Historia Ecclesiastica 1.11.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill, 12, citing Vita Constantini 1.19.

- ^ Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 7.32.4, qtd. and tr. D. S. Wallace-Hadrill, 12; Wallace-Hadrill cites J. H. Newman, The Arians of the Fourth Century (1890), 262, in 12 n. 4.

- ^ C.G. Bateman, Origen’s Role in the Formation of the New Testament Canon, 2010.

- ^ Quasten, 3.309.

- ^ Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 6.32.3–4; Kofsky, 12.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 333 n. 114, citing Eusebius, HE 6.32.1; In Is. pp. 195.20–21 Ziegler.

- ^ Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 6.32.3–4; Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 93; idem., "Eusebius of Caesarea", 2 col. 2.

- ^ Levine, 124–25.

- ^ Kofsky, 12, citing Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica 7.32.25. On Origen's school, see: Gregory, Oratio Panegyrica; Kofsky, 12–13.

- ^ Levine, 125.

- ^ Levine, 122.

- ^ a b c d e Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 94.

- ^ Quasten, 3.310.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill, 12 n. 1.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill, 11–12.

- ^ Quasten, 3.309–10.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 93, 95; Louth, "Birth of church history", 266.

- ^ Jerome, de Viris Illustribus 76, qtd. and tr. Louth, "Birth of church history", 266.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 93, 95.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 93–94.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 95.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 277; Wallace-Hadrill, 12–13.

- ^ Vermes, Geza (2012). Christian Beginnings from Nazareth to Nicea. Allen Lane the Penguin Press. p. 228.

- ^ Walker, Williston (1959). A History of the Christian Church. Scribner. p. 108.

- ^ Bruce L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, (2nd ed. Dallas, Texas: Word Publishing, 1995.), p.102.

- ^ Cameron, Averil; Hall, Stuart G., eds. (1999). Eusebius' Life of Constantine. Clarendon Ancient History. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-158847-1.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 112.

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 112–13, 340 n. 58.

- ^ Chesnut, Glenn F. (1986), "Introduction", The First Christian Histories: Eusebius, Socrates, Sozomen, Theodoret, and Evagrius

- ^ Maier, Paul L. (2007), Eusebius: The Church History – Translation and Commentary by Paul L. Maier, p. 9 and 16

- ^ See, e.g., James the Brother of Jesus (book) by Robert Eisenman.

- ^ "Ecclesiastical History", Catholic Encyclopedia, New Advent

- ^ a b c d e f Bardill, Jonathan; Bardill (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. pp. 159–170. ISBN 978-0-521-76423-0.

- ^ a b c Eusebius of Caesarea, Vita Constantini, 1.29

- ^ Lactantius, De mortibus persecutorum, 44.5–6

- ^ Thomas Hagg, "Hierocles the Lover of Truth and Eusebius the Sophist," SO 67 (1992): 138–50

- ^ Aaron Johnson, "The Author of the Against Hierocles: A Response to Borzì and Jones," JTS 64 (2013): 574–594)

- ^ Aaron Johnson, "The Tenth Book of Eusebius' General Elementary Introduction: A Critique of the Wallace-Hadrill Thesis," Journal of Theological Studies, 62.1 (2011): 144–160

- ^ Eusebius, Bishop of Caesarea On the Theophania, or Divine Manifestation of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ (Cambridge, 1843), pp. xxi–xxii. Lee's full passage is as follows: "As to the period at which it was written, I think it must have been, after the general peace restored to the Church by Constantine, and before either the "Praeparatio", or the "Demonstratio Evangelica", was written. My reason for the first of these suppositions is: Our author speaks repeatedly of the peace restored to the Church; of Churches and Schools restored, or then built for the first time : of the nourishing state of the Church of Caesarea; of the extended, and then successfully extending, state of Christianity : all of which could not have been said during the times of the last, and most severe persecution. My reasons for the second of these suppositions are, the considerations that whatever portions of this Work are found, either in the "Praeparatio", |22 the "Demonstratio Evangelica", or the " Oratio de laudibus Constantini", they there occur in no regular sequence of argument as they do in this Work: especially in the latter, into which they have been carried evidently for the purpose of lengthening out a speech. Besides, many of these places are amplified in these works, particularly in the two former as remarked in my notes; which seems to suggest, that such additions were made either to accommodate these to the new soil, into which they had been so transplanted, or, to supply some new matter, which had suggested itself to our author. And again, as both the "Praeparatio" and "Demonstratio Evangelica", are works which must have required very considerable time to complete them, and which would even then be unfit for general circulation; it appears probable to me, that this more popular, and more useful work, was first composed and published, and that the other two,--illustrating as they generally do, some particular points only,--argued in order in our Work,-- were reserved for the reading and occasional writing of our author during a considerable number of years, as well for the satisfaction of his own mind, as for the general reading of the learned. It appears probable to me therefore, that this was one of the first productions of Eusebius, if not the first after the persecutions ceased."

- ^ Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius (Harvard, 1981), p. 367, n.176. Note that Lee (p. 285) thinks that the passage in V. 1 refers to an earlier section within the Theophania itself, rather than to the Demonstratio.

- ^ Caesaea, Eusebius of; Miller, David J. D.; McCollum, Adam C.; Downer, Carol; Zamagni, Claudio (2010-03-06). Eusebius of Caesarea: Gospel Problems and Solutions (Ancient Texts in Translation): Roger Pearse, David J Miller, Adam C McCollum: 9780956654014: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-0956654014.

- ^ Georg Graf, Geschichte der christlichen arabischen Literatur vol. 1

- ^ The Christian Examiner, Volume One, published by James Miller, 1824 Edition, p. 66

- ^ David M. Gwynn, "From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy" [Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 47 (2007) 225–251], p. 227-245.

- ^ Beatrice, Pier Franco (June 2002). "The Word "Homoousios" from Hellenism to Christianity". Church History. 71 (2): 243–272. doi:10.1017/S0009640700095688. JSTOR 4146467. S2CID 162605872.

- ^ Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, Book 1, Chapter 1

- ^ See Gibbon's Vindication for examples of the accusations that he faced.

- ^ "Eusebius of Caesarea: Praeparatio Evangelica (translated by E.H. Gifford)". tertullian.org. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- ^ "Data for discussing the meaning of pseudos and Eusebius in PE XII, 31". tertullian.org. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "The gravest of the ecclesiastical historians, Eusebius himself, indirectly confesses, that he has related whatever might redound to the glory, and that he has suppressed all that could tend to the disgrace, of religion." (History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol II, Chapter XVI)

- ^ "Such an acknowledgment will naturally excite a suspicion that a writer who has so openly violated one of the fundamental laws of history has not paid a very strict regard to the observance of the other; and the suspicion will derive additional credit from the character of Eusebius, which was less tinctured with credulity, and more practised in the arts of courts, than that of almost any of his contemporaries." (History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol II, Chapter XVI)

- ^ Burgess, R. W., and Witold Witakowski. 1999. Studies in Eusebian and Post-Eusebian chronography 1. The "Chronici canones" of Eusebius of Caesarea: structure, content and chronology, AD 282–325 – 2. The "Continuatio Antiochiensis Eusebii": a chronicle of Antioch and the Roman Near East during the Reigns of Constantine and Constantius II, AD 325–350. Historia (Wiesbaden, Germany), Heft 135. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner. Page 69.

- ^ "J.B. Lightfoot, Eusebius of Caesarea". tertullian.org. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Averil Cameron, Stuart G. Hall, Eusebius' Life of Constantine. Introduction, translation and commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Pp. xvii + 395. ISBN 0-19-814924-7. Reviewed in BMCR

Sources

- Barnes, Timothy D. (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-16530-4.

- Eusebius (1999). Life of Constantine. Averil Cameron and Stuart G. Hall, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814924-8.

- Drake, H. A. (2002). Constantine and the bishops the policy of intolerance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7104-7.

- Kofsky, Aryeh (2000). Eusebius of Caesarea against paganism. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11642-9.

- Lawlor, Hugh Jackson (1912). Eusebiana: essays on the Ecclesiastical history of Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Levine, Lee I. (1975). Caesarea under Roman rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04013-7.

- Louth, Andrew (2004). "Eusebius and the Birth of Church History". In Young, Frances; Ayres, Lewis; Louth, Andrew (eds.). The Cambridge history of early Christian literature. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 266–274. ISBN 978-0-521-46083-5.

- Momigliano, Arnaldo (1989). On pagans, Jews, and Christians. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6218-0.

- Newman, John Henry (1890). The Arians of the Fourth Century (7th ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Sabrina Inowlocki & Claudio Zamagni (eds), Reconsidering Eusebius: Collected papers on literary, historical, and theological issues (Leiden, Brill, 2011) (Vigiliae Christianae, Supplements, 107).

- Wallace-Hadrill, D. S. (1960). Eusebius of Caesarea. London: A. R. Mowbray.

Further reading

- Attridge, Harold W.; Hata, Gohei, eds. (1992). Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism. Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-2361-8.

- Chesnut, Glenn F. (1986). The first Christian histories : Eusebius, Socrates, Sozomen, Theodoret, and Evagrius (2nd ed.). Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-164-1.

- Drake, H. A. (1976). In praise of Constantine : a historical study and new translation of Eusebius' Tricennial orations. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09535-9.

- Eusebius (1984). The History of the Church from Christ to Constantine. G.A. Williamson, trans. New York: Dorset Press. ISBN 978-0-88029-022-7.

- Grant, Robert M. (1980). Eusebius as Church Historian. Oxford: Clarendon Pr. ISBN 978-0-19-826441-5.

- Valois, Henri de (1833). "Annotations on the Life and Writings of Eusebius Pamphilus". The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius Pamphilus. S. E. Parker, trans. Philadelphia: Davis.

External links

- WMF project links

Media related to Eusebius of Caesarea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Eusebius of Caesarea at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Eusebius at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Eusebius at Wikiquote Works by or about Eusebius of Caesarea at Wikisource

Works by or about Eusebius of Caesarea at Wikisource

- Primary sources

- Church History (Eusebius); The Life of Constantine (Eusebius), online at ccel.org.

- History of the Martyrs in Palestine (Eusebius), English translation (1861) William Cureton. Website tertullian.org.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, The Gospel Canon Tables

- Eusebius, Six extracts from the Commentary on the Psalms.

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Graeca with analytical indexes complete Greek text of Eusebius' works

- Works by or about Eusebius at the Internet Archive

- Works by Eusebius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Secondary sources

- "Eusebius" in New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia (1917)

- Eusebius of Caesarea at the Tertullian Project

- Extensive bibliography at EarlyChurch.org

- Chronological list of Eusebius's writings

- Eusebius

- 260s births

- 339 deaths

- 3rd-century Romans

- 3rd-century Greek people

- 4th-century Christian saints

- 4th-century Christian theologians

- 4th-century Greek people

- 4th-century historians

- 4th-century philosophers

- 4th-century Romans

- 4th-century writers

- Amillennialism

- Bishops of Caesarea

- Christian anti-Gnosticism

- Chronologists

- Church Fathers

- Historians of Christianity

- Historians of the Catholic Church

- Late Antique writers

- People of Roman Syria

- Roman-era Greek historians