Autonomous underwater vehicle

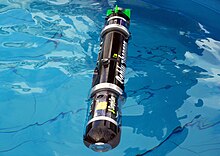

An autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) is a robot that travels underwater without requiring continuous input from an operator. AUVs constitute part of a larger group of undersea systems known as unmanned underwater vehicles, a classification that includes non-autonomous remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) – controlled and powered from the surface by an operator/pilot via an umbilical or using remote control. In military applications an AUV is more often referred to as an unmanned undersea vehicle (UUV). Underwater gliders are a subclass of AUVs.

History

The first AUV was developed at the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington as early as 1957 by Stan Murphy, Bob Francois and later on, Terry Ewart. The "Self-Propelled Underwater Research Vehicle", or SPURV, was used to study diffusion, acoustic transmission, and submarine wakes.

Other early AUVs were developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the 1970s. One of these is on display in the Hart Nautical Gallery in MIT. At the same time, AUVs were also developed in the Soviet Union[1] (although this was not commonly known until much later).

Applications

This type of underwater vehicles has recently become an attractive alternative for underwater search and exploration since they are cheaper than manned vehicles. Over the past years, there have been abundant attempts to develop underwater vehicles to meet the challenge of exploration and extraction programs in the oceans. Recently, researchers have focused on the development of AUVs for long-term data collection in oceanography and coastal management.[2]

Commercial

The oil and gas industry uses AUVs to make detailed maps of the seafloor before they start building subsea infrastructure; pipelines and sub sea completions can be installed in the most cost effective manner with minimum disruption to the environment. The AUV allows survey companies to conduct precise surveys of areas where traditional bathymetric surveys would be less effective or too costly. Also, post-lay pipe surveys are now possible, which includes pipeline inspection. The use of AUVs for pipeline inspection and inspection of underwater man-made structures is becoming more common.[citation needed] There also is development of AUVs for potential seabed mining and/or harvesting of polymetallic nodule rocks.[3]

Research

Scientists use AUVs to study lakes, the ocean, and the ocean floor. A variety of sensors can be affixed to AUVs to measure the concentration of various elements or compounds, the absorption or reflection of light, and the presence of microscopic life. Examples include conductivity-temperature-depth sensors (CTDs), fluorometers, and pH sensors. Additionally, AUVs can be configured as tow-vehicles to deliver customized sensor packages to specific locations.

The Applied Physics Lab at the University of Washington has been creating iterations of its Seaglider AUV platform since the 1950s. Though the Seaglider was originally designed for oceanographic research, in recent years it has seen much interest from organizations such as the U.S. Navy or the oil and gas industry. The fact that these autonomous gliders are relatively inexpensive to manufacture and operate is indicative of most AUV platforms that will see success in myriad applications.[4][weasel words][vague][clarification needed]

An example of an AUV interacting directly with its environment is the Crown-Of-Thorns Starfish Robot (COTSBot) created by the Queensland University of Technology (QUT). The COTSBot finds and eradicates crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), a species that damages the Great Barrier Reef. It uses a neural network to identify the starfish and injects bile salts to kill it.[5]

Hobby

Many roboticists construct AUVs as a hobby. Several competitions exist which allow these homemade AUVs to compete against each other while accomplishing objectives.[6][7][8] Like their commercial brethren, these AUVs can be fitted with cameras, lights, or sonar. As a consequence of limited resources and inexperience, hobbyist AUVs can rarely compete with commercial models on operational depth, durability, or sophistication. Finally, these hobby AUVs are usually not oceangoing, being operated most of the time in pools or lake beds. A simple AUV can be constructed from a microcontroller, PVC pressure housing, automatic door lock actuator, syringes, and a DPDT relay.[9] Some participants in competitions create designs that rely on open-source software.[10]

Illegal drug traffic

Submarines that travel autonomously to a destination by means of GPS navigation have been made by illegal drug traffickers.[11][12][13][14]

Air crash investigations

Autonomous underwater vehicles, for example AUV ABYSS, have been used to find wreckage of missing airplanes, e.g. Air France Flight 447,[15] and the Bluefin-21 AUV was used in the search for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.[16]

Military applications

The U.S. Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) Master Plan[17] identified the following UUV's missions:

- Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance

- Mine countermeasures

- Anti-submarine warfare

- Inspection/identification

- Oceanography

- Communication/navigation network nodes

- Payload delivery

- Information operations

- Time-critical strikes

The Navy Master Plan divided all UUVs into four classes:[18]

- Man-portable vehicle class: 25–100 lb displacement; 10–20 hours endurance; launched from small water craft manually (i.e., Mk 18 Mod 1 Swordfish UUV)

- Lightweight vehicle class: up to 500 lb displacement, 20–40 hours endurance; launched from RHIB using launch-retriever system or by cranes from surface ships (i.e., Mk 18 Mod 2 Kingfish UUV)

- Heavyweight vehicle class: up to 3,000 lb displacement, 40–80 hours endurance, launched from submarines

- Large vehicle class: up to 10 long tons displacement; launched from surface ships and submarines

In 2019, the Navy ordered five Orca UUVs, its first acquisition of unmanned submarines with combat capability.[19]

Vehicle designs

Hundreds of different AUVs have been designed over the past 50 or so years,[20] but only a few companies sell vehicles in any significant numbers. There are around 10 companies that sell AUVs on the international market, including Kongsberg Maritime, HII (formerly Hydroid, and previously owned by Kongsberg Maritime)[21]), Bluefin Robotics, Teledyne Gavia (previously known as Hafmynd), International Submarine Engineering (ISE) Ltd, Atlas Elektronik, RTsys,[22] MSubs[23] and OceanScan.[24]

Vehicles range in size from man portable lightweight AUVs to large diameter vehicles of over 10 metres length. Large vehicles have advantages in terms of endurance and sensor payload capacity; smaller vehicles benefit significantly from lower logistics (for example: support vessel footprint; launch and recovery systems).

Some manufacturers have benefited from domestic government sponsorship including Bluefin and Kongsberg. The market is effectively split into three areas: scientific (including universities and research agencies), commercial offshore (offshore energy, marine minerals etc.) and defence related applications (mine countermeasures, battle space preparation). The majority of these roles utilize a similar design and operate in a cruise (torpedo-type) mode. They collect data while following a preplanned route at speeds between 1 and 4 knots.

Commercially available AUVs include various designs, such as the small REMUS 100 AUV originally developed by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US and now produced commercially by HII; the HUGIN Family of AUVs comprising HUGIN, HUGIN Edge, HUGIN Superior and HUGIN Endurance developed by Kongsberg Maritime and Norwegian Defence Research Establishment; the Bluefin Robotics 12-and-21-inch-diameter (300 and 530 mm) vehicles; the ISE Ltd. Explorer; Cellula Robotics' Solus LR; the RT Sys Comet and NemoSens AUVs; Teledyne's Gavia, Osprey and SeaRaptor; and the L3 Harris Ocean Server Iver range of AUVs.

Most AUVs fall into the survey class or cruising AUVs, in a cylindrical or torpedo shape with a powered propeller. This is seen as the best compromise between size, usable volume, hydrodynamic efficiency and ease of handling. There are some vehicles that make use of a modular design, enabling components to be changed easily by the operators. Some recent developments move away from the traditional cylindrical shape in favour of other arrangements such as Saab's Sabretooth hybrid R/AUV or the recently launched HUGIN Edge. These either optimise the shape according to the operational requirements (Sabretooth) or to benefit from low drag hydrodynamic performance (HUGIN Edge).

The market has matured since 2010 with greater emphasis on data than on vehicle characteristics. Operators are more technically aware and the utilisation of AUVs has increased commensurately. More operators use their systems autonomously, rather than supervising the vehicles using an acoustic link. Consequently, on-board processing and in-mission autonomy have become more important features for AUVs. Most AUVs have what is considered navigational or event-based autonomy. They will follow a geographic mission plan with distinct events to operate sensors, change course or return to the surface. Some AUVs have adaptive autonomy, for example the ability to adjust course to avoid obstacles along the planned route. The current state of the art is a vehicle that collects, processes and acts on the data it has acquired without operator input.

As of 2008, a new class of AUVs are being developed, which mimic designs found in nature. Although most are currently in their experimental stages, these biomimetic (or bionic) vehicles are able to achieve higher degrees of efficiency in propulsion and maneuverability by copying successful designs in nature. Two such vehicles are Festo's AquaJelly (AUV)[25] and the EvoLogics BOSS Manta Ray.[26]

Sensors

AUVs carry sensors to navigate autonomously and map features of the ocean. Typical sensors include compasses, depth sensors, sidescan and other sonars, magnetometers, thermistors and conductivity probes. Some AUVs are outfitted with biological sensors including fluorometers (also known as chlorophyll sensors), turbidity sensors, and sensors to measure pH, and amounts of dissolved oxygen.

A demonstration at Monterey Bay, in California, in September 2006, showed that a 21-inch (530 mm) diameter AUV can tow a 400 feet (120 m)-long hydrophone array while maintaining a 6-knot (11 km/h) cruising speed.[citation needed]

Navigation

Radio waves cannot penetrate water very far, so as soon as an AUV dives it loses its GPS signal. Therefore, a standard way for AUVs to navigate underwater is through dead reckoning. Navigation can however be improved by using an underwater acoustic positioning system. When operating within a net of sea floor deployed baseline transponders this is known as LBL navigation. When a surface reference such as a support ship is available, ultra-short baseline (USBL) or short-baseline (SBL) positioning is used to calculate where the sub-sea vehicle is relative to the known (GPS) position of the surface craft by means of acoustic range and bearing measurements. To improve estimation of its position, and reduce errors in dead reckoning (which grow over time), the AUV can also surface and take its own GPS fix. Between position fixes and for precise maneuvering, an Inertial Navigation System on board the AUV calculates through dead reckoning the AUV position, acceleration, and velocity. Estimates can be made using data from an Inertial Measurement Unit, and can be improved by adding a Doppler Velocity Log (DVL), which measures the rate of travel over the sea/lake floor. Typically, a pressure sensor measures the vertical position (vehicle depth), although depth and altitude can also be obtained from DVL measurements. These observations are filtered to determine a final navigation solution.

Propulsion

There are a couple of propulsion techniques for AUVs. Some of them use a brushed or brush-less electric motor, gearbox, Lip seal, and a propeller which may be surrounded by a nozzle or not. All of these parts embedded in the AUV construction are involved in propulsion. Other vehicles use a thruster unit to maintain the modularity. Depending on the need, the thruster may be equipped with a nozzle for propeller collision protection or to reduce noise submission, or it may be equipped with a direct drive thruster to keep the efficiency at the highest level and the noises at the lowest level.[27] Advanced AUV thrusters have a redundant shaft sealing system to guarantee a proper seal of the robot even if one of the seals fails during the mission.[citation needed]

Underwater gliders do not directly propel themselves. By changing their buoyancy and trim, they repeatedly sink and ascend; airfoil "wings" convert this up-and-down motion to forward motion. The change of buoyancy is typically done through the use of a pump that can take in or push out water. The vehicle's pitch can be controlled by moving the center of mass of the vehicle. For Slocum gliders this is done internally by moving the batteries, which are mounted on a screw.[28] Because of their low speed and low-power electronics, the energy required to cycle trim states is far less than for regular AUVs, and gliders can have endurances of months and transoceanic ranges.[citation needed]

Communications

Since radio waves do not propagate well under water, many AUV's incorporate acoustic modems to enable remote command and control. These modems typically utilize proprietary communications techniques and modulation schemes. In 2017 NATO ratified the ANEP-87 JANUS standard for subsea communications. This standard allows for 80 BPS communications links with flexible and extensible message formatting.[citation needed] Alternative communication techniques are being explored, including optical, inductive and RF based techniques, which may be combined in a multi-modal solutions.[29] Evaluations are also being conducted on novel communication techniques which are able to utilize the infrastructure as a communication path to provide alternative communication paths and opportunities from the vehicles.[30]

Power

Most AUVs in use today are powered by rechargeable batteries (lithium ion, lithium polymer, nickel metal hydride etc.), and are implemented with some form of battery management system. Some vehicles use primary batteries which provide perhaps twice the endurance—at a substantial extra cost per mission. Previously some systems used aluminum based semi-fuel cells, but these require substantial maintenance, require expensive refills and produce waste product that must be handled safely. An emerging trend is to combine different battery and power systems with supercapacitors.[citation needed]

See also

- Intervention AUV – Type of autonomous underwater vehicle capable of autonomous interventions

- Underwater glider – Type of autonomous underwater vehicle

- Bionics – Application of natural systems to technology

- Biomimetics – Imitation of biological systems for the solving of human problems

- Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute – American oceanographic research institute

- Office of Naval Research – Office within the United States Department of the Navy

- National Oceanography Centre, Southampton – Centre for research, teaching, and technology development in Ocean and Earth science

- DeepC – Autonomous underwater vehicle powered by a fuel cell

- National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology – Research organisation within NOAA

- AUV-150 – Unmanned underwater vehicle in development in by Central Mechanical Engineering Research Institute

- REMUS (AUV) – Autonomous underwater vehicle series

- MAYA AUV – Autonomous underwater vehicle from National Institute of Oceanography, India

- Torpedo – Self-propelled underwater weapon

- Theseus (AUV) – Large autonomous underwater vehicle for laying fibre-optic cable

- Eelume – Autonomous underwater vehicle being developed by Eelume AS

References

- ^ Autonomous Vehicles at the Institute of Marine Technology Problems Archived May 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saghafi, Mohammad; Lavimi, Roham (2020-02-01). "Optimal design of nose and tail of an autonomous underwater vehicle hull to reduce drag force using numerical simulation". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part M: Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment. 234 (1): 76–88. doi:10.1177/1475090219863191. ISSN 1475-0902. S2CID 199578272.

- ^ "Impossible Metals demonstrates its super-careful seabed mining robot". New Atlas. 8 December 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ^ "Seaglider: Autonomous Underwater Vehicle".

- ^ Dayoub, F.; Dunbabin, M.; Corke, P. (2015). Robotic detection and tracking of Crown-of-thorns starfish. IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). doi:10.1109/IROS.2015.7353629.

- ^ "RoboSub". Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Designspark ChipKIT Challenge (this competition is now closed)

- ^ Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Competition

- ^ Osaka University NAOE Mini Underwater Glider (MUG) for Education Archived March 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Robotic Submarine Running Debian Wins International Competition". Debian-News. 2009-10-08. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ Kijk magazine, 3/2012[full citation needed]

- ^ Sharkey, Noel; Goodman, Marc; Ros, Nick (2010). "The Coming Robot Crime Wave" (PDF). Computer. 43 (8): 116–115. doi:10.1109/MC.2010.242. ISSN 0018-9162. S2CID 29820095.

- ^ Wired for war: The robotics revolution and conflict in the twenty-first century by P.W.Singer, 2009

- ^ Lichtenwald, Terrance G.,Steinhour, Mara H., and Perri, Frank S. (2012). "A maritime threat assessment of sea based criminal organizations and terrorist operations," Homeland Security Affairs Volume 8, Article 13.

- ^ "Malaysia Airlines: World's only three Abyss submarines readied for plane search". Telegraph.co.uk. 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Bluefin robot joins search for missing Malaysian plane - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ Department of the Navy, The Navy Unmanned Undersea Vehicle (UUV) Master Plan, 9 Nov 2004.

- ^ "Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Volume 32, Number 5 (2014)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ "The Navy is starting to put up real money for robot submarines". Los Angeles Times. 19 April 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ "AUV System Timeline". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ^ "KONGSBERG acquires Hydroid LLC" Kongsberg - Hydroid, 2007

- ^ "RTsys". www.rtsys.fr/.

- ^ rvarcoe (2018-03-27). "Unmanned Systems | Submergence Group | MSubs". Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- ^ "LAUV – Light Autonomous Underwater Vehicle". www.oceanscan-mst.com. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- ^ "AquaJelly" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Festo Corporate, 2008

- ^ "Products / R&D Projects / BOSS - Manta Ray AUV / Overview | EvoLogics GMBH". Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ "High Efficiency, Low Noise Underwater Thruster". lianinno.com. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Slocum Glider". www.whoi.edu. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Beatrice Tomasi, Marie B. Holstad, Ingvar Henne, Bard Henriksen, Pierre-Jean Bouvet, et al.. MarTERA UNDINA project: a multi-modal communication and network-aided positioning system for marine robotics and benthic stations. 28th annual Underwater Technology Conference - UTC'22, Jun 2022, Bergen, Norway. ⟨hal-03779076⟩

- ^ Mulholland, J.J.; Smolyaninov, I.I. (2022-08-30). "Plasmonic - Surface Electromagnetic Wave Communication for subsea asset inspection". 2022 Sixth Underwater Communications and Networking Conference (UComms). Lerici, Italy: IEEE. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1109/UComms56954.2022.9905693. ISBN 978-1-6654-7461-0. S2CID 252705048.

Bibliography

- Technology and Applications of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Gwyn Griffiths ISBN 978-0-415-30154-1

- Review of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) Developments doi:10.5962/bhl.title.39207 OCLC 227209412

- Masterclass in AUV Technology for Polar Science ISBN 978-0-906940-48-8

- The Operation of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles2 ISBN 978-0-906940-40-2

- 1996 Symposium on Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Technology ISBN 978-0-7803-3185-3

- Development of an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle ISBN 978-3-639-09644-6

- Optimal Control System for A Semi-Autonomous Underwater Vehicle ISBN 978-3-639-24545-5

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicles ISBN 978-1-4398-1831-2

- Recommended Code of Practice for the Operation of Autonomous Marine Vehicles ISBN 978-0-906940-51-8

- Autonomer Mobiler Roboter ISBN 978-1-158-80510-5

- Remotely operated underwater vehicle ISBN 978-613-0-30144-6

- Underwater Robots ISBN 978-3-540-31752-4

- The World AUV Market Report 2010-2019 ISBN 978-1-905183-48-7

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicles: Design and practice ISBN 978-1-78561-703-4