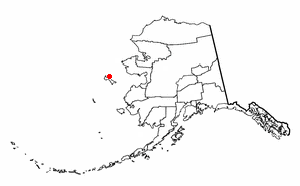

St. Lawrence Island

Closeup map of St. Lawrence Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Bering Sea |

| Coordinates | 63°21′44″N 170°16′02″W / 63.36222°N 170.26722°W |

| Area | 1,791.56 sq mi (4,640.1 km2) |

| Length | 90 mi (140 km) |

| Width | 22 mi (35 km) |

| Highest point | Atuk Mountain, 2,070 ft (630 m) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | Alaska |

| Largest settlement | Savoonga (pop. 835, 2020) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,475 (2020) |

| Pop. density | 0.32/km2 (0.83/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Siberian Yupik |

St. Lawrence Island (Template:Lang-ess, Russian: Остров Святого Лаврентия, romanized: Ostrov Svyatogo Lavrentiya) is located west of mainland Alaska in the Bering Sea, just south of the Bering Strait. The village of Gambell, located on the northwest cape of the island, is 50 nautical miles (95 kilometers) from the Chukchi Peninsula in the Russian Far East. The island is part of Alaska, but closer to Russia and Asia than to the Alaskan and North American mainland. St. Lawrence Island is thought to be one of the last exposed portions of the land bridge that once joined Asia with North America during the Pleistocene period.[1] It is the sixth largest island in the United States and the 113th largest island in the world. It is considered part of the Bering Sea Volcanic Province.[2] The Saint Lawrence Island shrew (Sorex jacksoni) is a species of shrew endemic to St. Lawrence Island.[3] The island is jointly owned by the predominantly Siberian Yupik villages of Gambell and Savoonga, the two main settlements on the island.[4][5]

Geography

The United States Census Bureau defines St. Lawrence Island as Block Group 6, Census Tract 1 of Nome Census Area, Alaska. As of the 2000 census there were 1,292 people living on a land area of 1,791.56 sq mi (4,640.1 km2).[6] The island is about 90 mi (140 km) long and 8–22 mi (13–35 km) wide. The island has no trees, and the only woody plants are Arctic willow, standing no more than a foot (30 cm) high.

The island's abundance of seabirds and marine mammals is due largely to the influence of the Anadyr Current, an ocean current which brings cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep waters of the Bering Sea shelf edge.

To the south of the island there was a persistent polynya in 1999, formed when the prevailing winds from the north and east blow the migrating ice away from the coast.[7]

The climate of Gambell is:

| January | April | July | October | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily max | 12 °F (−11 °C) | 20 °F (−7 °C) | 50 °F (10 °C) | 34 °F (1 °C) |

| Daily min | 3 °F (−16 °C) | 10 °F (−12 °C) | 41 °F (5 °C) | 29 °F (−2 °C) |

Villages

The island contains and is jointly owned by two villages: Savoonga and Gambell. The island is now inhabited mostly by Siberian Yupik engaged in hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding. As a result of having title to the land, the Yupik are legally able to sell the fossilized ivory and other artifacts found on St. Lawrence Island.

The St. Lawrence Island Yupik people are also known for their skill in carving, mostly with materials from marine mammals (walrus ivory and whale bone). The Arctic yo-yo may have evolved on the island. Anthropologist Lars Krutak has examined the tattoo traditions of the St. Lawrence Yupik.

History

Prehistory

In St. Lawrence Island, earliest evidence of habitation dates from 2,000 to 2,500 years ago. Artifacts resemble the Okvik (oogfik) style. Archaeological sites on the Punuk Islands, off the eastern end of St. Lawrence Island, at Kukulik, near Savoonga and on hill slopes above Gambell, all indicate evidence of Okvik habitation. Okvik decorative style is zoomorphic and elaborate. Sometimes crude engraving, with greater variation than the Old Bering Sea and Punuk styles.

Okvik habitation, influenced by Old Bering Sea habitation of 2000 to 700 years ago,[8] is characterized by the simpler and more homogeneous Punuk style. Stone artifacts changed from chipped stone to ground slate; carved ivory harpoon heads are smaller and simpler in design.

Prehistoric and early historic settlements of St. Lawrence Island were temporary. Periods of abandonment and reoccupation depended on resources along with favorable climate. Famine occurred, shown by Harris lines and enamel hypoplasia in human skeletons. With travel to and from the mainland during calm weather, the island was used as a hunting base. Sites were re-used occasionally rather than permanently.

Major archaeology sites at Gambell and Savoonga (Kukulik) were excavated by Otto Geist and Ivar Skarland of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Collections from these excavations are curated at the University of Alaska Museum on the UAF campus.

Arrival of Europeans

The island is called Sivuqaq by the Yupik who live there.[9] It was visited by Russian/Danish explorer Vitus Bering on St. Lawrence's Day, August 10, 1728, and named after the day of his visit. The island was the first place in Alaska known to have been visited by European explorers.

There were about 4,000 Central Alaskan Yupik and Siberian Yupik living in several villages on the island in the mid-19th century. They subsisted by hunting walrus and whale and by fishing. The famine in 1878–1880 caused many to starve and many others to leave, decimating the island's population. A revenue cutter visited the island in 1880 and estimated that out of 700 inhabitants, 500 were found dead of starvation. Reports of the day put the blame on traders' supplying the people with liquor causing the people to ″neglect laying up their usual supply of provisions″.[10] Nearly all the residents remaining were Siberian Yupik.

Reindeer were introduced on the island in 1900 in an attempt to bolster the economy. The reindeer herd grew to about 10,000 animals by 1917, but has since declined. Reindeer are herded as a source of subsistence meat to this day. In 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt established a reindeer reservation on the island.[11] This caused legal issues in the indigenous land claim process to acquire surface and subsurface rights to their land, under the section 19 of Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) as they had to prove that the reindeer reserve was set up to support the indigenous people rather than to protect the reindeer themselves.[12]

World War II

During World War II, islanders served in the Alaska Territorial Guard (ATG). Following disbandment of the ATG in 1947, and with the construction of Northeast Cape Air Force Station in 1952, many islanders joined the Alaska National Guard to provide for the defense of the island and station.

Cold War to Present

On June 22, 1955, during the Cold War, a US Navy P2V Neptune with a crew of 11 was attacked by two Soviet Air Forces fighter aircraft along the International Date Line in international waters over the Bering Straits, between Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula and Alaska. The P2V crashed on the island's northwest cape, near the village of Gambell. Villagers rescued the crew, 3 of whom were wounded by Soviet fire and 4 of whom were injured in the crash. The Soviet government, in response to a US diplomatic protest, was unusually conciliatory, stating that:

There was an exchange of shots after a Soviet fighter advised the US plane that it was over Soviet territory and should leave (the US denied that the US plane fired at all). The incident took place under heavy cloud cover and poor visibility, although the alleged violation of Soviet airspace could be the responsibility of US commanders not interested in preventing such violations.

The Soviet military was under strict orders to "avoid any action beyond the limits of the Soviet state frontiers."

The Soviet government "expressed regret in regard to the incident," and, "taking into account... conditions which do not exclude the possibility of a mistake from one side or the other," was willing to compensate the US for 50% of damages sustained—the first such offer ever made by the Soviets for any Cold War shoot-down incident.

The US government stated that it was satisfied with the Soviet expression of regret and the offer of partial compensation, although it said that the Soviet statement also fell short of what the available information indicated.[13]

Northeast Cape Air Force Station, at the island's other end, was a United States Air Force facility consisting of an Aircraft Control and Warning[14] (AC&W) radar site, a United States Air Force Security Service listening post; and a White Alice Communications System (WACS) site that operated from about 1952 to about 1972. The area surrounding the Northeast Cape base site had been a traditional camp site for several Yupik families for centuries. After the base closed down in the 1970s, many of these people started to experience health problems. Even today, people who grew up at Northeast Cape have high rates of cancer and other diseases, possibly due to PCB exposure around the site.[15] According to the State of Alaska, those elevated cancer rates have been shown to be comparable to the rates of other Alaskan and non-Alaskan arctic natives who were not exposed to a similar Air Force facility.[16] The majority of the facility was removed in a $10.5 million cleanup program in 2003. Monitoring of the site will continue into the future.[17]

After the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, the villages of Savoonga and Gambell opted out of selling their land to the federal government and joining a larger regional Native corporation. In return, they were promised full ownership of St Lawrence Island. In 2016, after completing a decades-long land survey, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management transferred permanent private ownership of the island to the two corporations representing Savoonga and Gambell.[5][4]

St. Lawrence Island made national news when Nanuq, an Australian Shepherd dog from Gambell, Alaska, was rescued and returned. The one-year-old dog belonged to a young Yupik named Mandy Iworrigan, who took the dog to Savoonga, where it disappeared. It was found weeks later in Wales on the Alaskan mainland. Large areas of the surrounding sea were covered by ice at the time. The dog is believed to have survived the 150-mile crossing by catching wild game. After posts about a lost dog in Wales were posted on social media, Nanuq was recognized and returned to its owner.[18]

Transportation

The airports are Gambell Airport and Savoonga Airport.

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ "Tools and Implements: St. Lawrence Island and the Bering Strait Region". University of Missouri-Columbia Museum of Anthropology. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ The 40Ar/39Ar chronology and eruption rates of Cenozoic volcanism in the eastern Bering Sea Volcanic Province, Alaska

- ^ "Wildlife Notebook Series: Shrews". Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

- ^ a b "St. Lawrence Island corporations get clear title to their land". The Nome Nugget. 2016-08-05. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ a b KTUU, Travis Khachatoorian /. "Million-acre St. Lawrence Island land title signed over to native population". www.alaskasnewssource.com. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ Block Group 6, Census Tract 1, Nome Census Area United States Census Bureau

- ^ "St Lawrence Polynya". Polar Research at UW Oceanography. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ "Archeology of the Tundra and Arctic Alaska". nps.gov. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- ^ "Arctic Studies".

- ^ "A Starving Population". The Cornishman. No. 122. 11 November 1880. p. 3.

- ^ Government of Alaska 2018

- ^ Case & Voluck 2012, p. 88

- ^ "VP-9 Mishap". June 22, 1955: US Navy Aircraft Attacked Over Bering Sea. U. S. Navy Patrol Squadrons. 24 Jan 2011. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ "Aircraft Control And Warning System". DoD. About.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

A system established to control and report the movement of aircraft. It consists of observation facilities (radar, passive electronic, visual, or other means), control center, and necessary communications.

- ^ Coming Clean network. "PCB's in People of St. Lawrence Island". Body Burden Report. Archived from the original on 2006-06-18. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin. PCB Blood Test Results from St. Lawrence Island. February 6, 2003.

- ^ State of Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation. "St. Lawrence Island". Contaminated Sites Program. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ NBC News:April 13, 2023:News:U.S. News: Homeward bound lost dog returns home surviving epic 150 mile journey

References

- Case, David S.; Voluck, David A. (2012). Alaska Natives and American Laws: Third Edition. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 9781602231764. - Total pages: 520

- Government of Alaska (2018). "History". Government of Alaska. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

External links

- Gambell and St. Lawrence Island Photos from Gambell and St. Lawrence Island, August 2001

- Video on St. Lawrence