Living in the Age of Airplanes

| Living in the Age of Airplanes | |

|---|---|

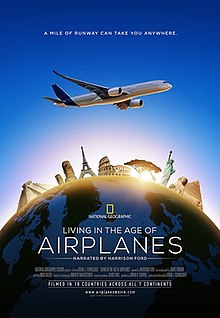

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brian J. Terwilliger |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Narrated by | Harrison Ford |

| Cinematography | Andrew Waruszewski |

| Edited by | Brad Besser |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production company | Terwilliger Productions |

| Distributed by | National Geographic Films |

Release dates | |

Running time | 47 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | US$8,011 (Australia and United Kingdom) |

Living in the Age of Airplanes is a 2015 American epic documentary film written, directed, and produced by Brian J. Terwilliger. Narrated by Harrison Ford, it explores the way commercial aviation has revolutionized transportation and the many ways it affects everyday lives, and it concludes with a positive endorsement of flying. The film's themes include connections and perspectives, using several cinematographic styles to convey its message.

Terwilliger conceived the idea of the film in 2007, two years after releasing his feature directorial debut One Six Right. He intended it as a reliving of the feeling of flying for the first time and a celebration of the aviation industry. Production began independently in 2009, with filming taking place a year later in eighteen countries across all seven continents, becoming the first IMAX film to be made on such a scale. It used the first entry of the Arri Alexa digital camera. Filming took over 100 days. Post-production took place between 2013 and 2014. James Horner, who died in 2015, composed the score later released in 2016. Despite having 260 hours of raw footage, the film's becomes only 47 minutes long when edited, and divided to five chapters.

Living in the Age of Airplanes was initially planned to be released as Aviation: The Invisible Highway before National Geographic Films acquired it for distribution. It premiered on April 6, 2015 on a special Emirates flight, before being released in select IMAX and museum theaters on April 8. Ford's accident in his airplane during the time of its premiere attracted more interest in the film. It was released for streaming and on home video in 2016. Critics praised its technical and narrative aspects but some felt it lacked comprehensiveness on the history and disadvantages of aviation; fans of One Six Right were disappointed by its difference. Terwilliger disagreed with most of the criticisms. The film won three awards, two of which in regards to Horner's score.

Summary

Living in the Age of Airplanes is divided into five chapters and has a standalone opening with a quote from Bill Gates: "The airplane became the first World Wide Web, bringing people, languages, ideas, and values together".

The first chapter, "The World Before the Airplane", observes that the first mode of transportation, walking, took "a lifetime". Geographically isolated, humans mapped the universe before the Earth and were unaware of other cultures. Walking remained the only transportation for over 195,000 years until the invention of the wheel. 4,500 years later came the advent of mechanical transportation which, though faster and more efficient, was still restricted by the nature of land and sea. Airplanes are considered revolutionary; where others could only travel at around 10 miles per hour (16 km/h), they could fly at speeds up to 500 miles per hour (800 km/h); they can also cross land and sea, and do not mandate airports.

The second chapter, "The Portal to the Planet", says aviation is crucial to connecting the world and is the equivalent of time travel: a bridge between cultures. Each day, around 100,000 take-offs and landings occur, and over 250,000 people board flights "at any moment in time". The third chapter, "Redefining Remote", depicts Maldives, a country that is accessible with seaplanes, since its small islands and shallow waters, make airports difficult to build and ships impossible to approach. Despite the difficult terrain, airplanes reach Antarctica, a remote continent, making it accessible to tourists and researchers. The fourth chapter, "The World Comes to Us", depicts cargo aviation, which allows products to be quickly shipped worldwide; flowers' perishable nature had restricted shipments to just country-wide, but with cargo they can be shipped anywhere long before they perish. Thanks to air travel, Las Vegas became the largest convention hub, and in a way, those who have never flown are impacted by rapidly-growing industries.

The final chapter, "Perspective", laments that flying has become ordinary and lost its joyousness, becoming frustrating. However, the film says, "every era is a golden age, it's just a matter of perspective", using aviation as philosophy to endorse an appreciation of the present moment and asking audiences to imagine a world without aviation. It then says no virtual technology can replace aviation's ability in bringing people physically close. After saying "the most meaningful [place one could go with airplanes] is home", it ends with scenes of landed passengers embracing their waiting loved ones.

Production

Pre-production

In 2005, Brian J. Terwilliger released his feature directorial debut One Six Right, which focuses on general aviation from the viewpoint of pilots, under his company Terwilliger Productions.[1] It has since gained a cult following among aviation enthusiasts.[2] In 2007, he conceived the idea of a film focusing on the impact of commercial aviation on society. He planned the film would give context to aviation to relive its wonder and hoped audiences would "not look at flying the same way again".[3] He described the film as a "love letter" to the aviation industry.[4]

Terwilliger wrote the narration with Jessica Grogan, and Daniel Oppenheimer wrote additional narration.[5] The working title was Aviation Epic, in reference to the film's large scale and ambitious nature.[2] Terwilliger chose to show the difficulty of pre-aviation life to make the film relatable,[6] and gave it a philosophical theme, comparing aviation to the Internet, which "could help us share ideas and communicate with other people so quickly now. We can create another [t]weet and the whole world knows what you are thinking in seconds."[7]

According to Terwilliger, pre-production included months of getting filming permits and finding crew members who would help the filming process, such as language interpreters and drivers. He considered the logistical aspect of production the most challenging. He initially pitched the idea to National Geographic Films but decided to keep the production independent, as he had on One Six Right, to make it true to his vision, worrying National Geographic would try altering his ideas and become involved in the production process, losing his creative control. According to him, the film's budget was relatively high.[3] The film was first announced without a title on September 15, 2014, in an interview with podcast Film Courage. Amid pre-production, a short film called Flying Full Circle, in which Terwilliger flew with the Blue Angels, was made.[8]

Filming

Principal photography was done in 95 locations, in 18 countries on all seven continents: Africa,[a] Antarctica,[b] Asia,[c] Europe,[d] North America,[e] Oceania,[f] and South America.[g] Within the United States, they filmed in the states of Alaska,[h] Arizona,[i] California,[j] Hawaii,[k] Nevada,[l] North Carolina,[m] Tennessee,[n] and Utah.[o][5] This makes it the first IMAX film to be filmed at such scale.[3] Filming began in 2010 when the first Arri Alexa camera was released; the crew decided to purchase its seventh iteration before the model was made available to the public.[3][9][10] They were unable to use film cameras due to financial and logistical shortcomings.[11] Other filming equipment included prime and zoom lenses, a triangular jib, sound equipment, and various kinds of support, which weighed over 160 lb (73 kg). Terwilliger said in the film's production notes; "Just getting to the locations could be a real challenge. One day in Costa Rica, we went to shoot suspension bridges] and ended up hiking 4.5 miles (7.2 km) in and out of the forest with all this gear. [H]alf the job is carrying equipment, the other half is actually shooting." There were four skeleton crews. Andrew Waruszewski, who had filmed documentaries for National Geographic, was engaged as cinematographer upon recommendation to Terwilliger by producer Bryan H. Carroll. Terwilliger said Waruszewski had the attention to detail and level of commitment he was looking for. Discussions about the cinematography included symmetry and tone; Terwilliger wanted every shot in the film to look "like a commercial".[9][12]

The crew began filming in Mojave Air and Space Port, the first scene in the film,[12] and continued to the GE Aviation and Airbus factory, where components for an Emirates Airbus A380 were being assembled.[13] A Canon EOS 5D was used for time-lapse sequences, which were photographed by Ben Wiggins, who was of the splinter unit: at times separate from the main crew, and at times would leapfrog each other.[3] In certain scenes, such as those featuring Hunts Mesa, he would have two 5Ds; one acting still and another doing a hyperlapse.[14] Meanwhile, Terwilliger had Doug Allan filming the South Pole scenes for 11 nights in January.[p] Despite his longtime experience of living in Antarctica, Allan had never visited the South Pole until filming for Living in the Age of Airplanes.[9] Helicopters, such as the Eurocopter AS350 Écureuil,[15] were used for aerial shots except for those in Maldives, where a chartered seaplane was used because helicopters are outlawed in that country.[3] Other cinematographers were engaged for aerial and underwater scenes in Australia, Kenya, Maldives, and the United States. Some scenes were filmed in a Qantas Airbus A380 flying a Los Angeles-Sydney route.[16]

In "The World Comes to Us", Terwilliger chose a flower as the primary object to depict cargo aviation because it is "timeless", culturally appreciative, and perishable.[2] The film crew followed a shipment of roses from Kenya as they travel to an Alaskan house, transiting at an Amsterdam warehouse and Memphis International Airport.[17] When they arrived at the house and began setting up their filming equipment, the roses arrived. Terwilliger wanted the roses to have arrived from Kenya to make the film's message genuine.[18]

Although some shots were planned using flight data from FlightAware,[5] some were impromptu at the cost of the crew staying in the locations for extra days. Impromptu shots include those of airplanes flying above ancient monuments, "juxtaposing the old and the new",[3] and a shot of a Trans Maldivian Airways seaplane nearing a shipwreck, which required the crew to organize with the pilots.[2] At times, the crew would revisit prior filming locations to reshoot. Generally, the crew stayed a few days at each location; they spent 16 days in the Maldives, with poor weather further extending it.[7] Terwilliger considered the entire Maldivian scene the best.[19]

In some instances, poor weather prohibited filming; in one instance, San Francisco fog filled up the Golden Gate Bridge as they intended to film it from a location they reserved for only a day.[20] The shot of a hermit crab crawling over the Maldivian sands took two hours to film while the crew instructed the crab to move in the required direction; prior, several other crabs were "auditioned".[10] According to Terwilliger, he and the crew felt privileged they "got to experience many things that [the] film talked about".[7] Filming ended in 2012, lasting over 100 days.[21] The crew filmed 260 hours of footage, only 47 minutes of which were used because IMAX theaters have hourly showtimes.[3] According to Terwilliger; "We just shot and shot and shot, even though I know we'll never use this ... Most of the time I was right: We didn't use it. But sometimes we did. When you have those options later, it's a beautiful thing."[2]

Post-production

Terwilliger wanted an A-list narrator and score composer for the film, and wanted the narrator to have experience with aviation. Harrison Ford, who is also a pilot, recognized Terwilliger from One Six Right and accepted his offer to narrate the film, which was done over three days in early 2014. Ford narrated the entire rough cut of the film, watching it five times to "get into the character".[2] James Horner befriended Terwilliger in 2008 at an air show;[22] he agreed to compose the score.[2] His goal was to provide a spiritual feeling to match the film's tone,[23] also marrying aviation and music.[24] It was released digitally in a soundtrack album on September 14, 2016, coinciding the film's digital and physical release.[25] It was released in CD through Intrada Records on August 23, 2017.[26]

The film's five-chapter structure was not conceived until editing began in 2014.[2] Brad Besser, who has worked on The Pacific, was chosen as the film's editor; he and Terwilliger had "gathered clips from the Internet to build a rough video storyboard for the entire film" prior to filming.[9] Because of the film's non-linear nature, Terwilliger described dividing it into chapters as a challenging process. There are some subtle stories—a frustrated family is seen at the beginning but is revealed at the end to be waiting for a loved one—though those were not planned.[2]

Choosing which shots to use was also noted to be frustrating, though it was simplified by removing shots depicting poor weather.[7] Archival and stock footage were licensed from Periscope Films, the Mitch Dakleman Collection, the UCLA Film & Television Archive, and Budget Films. Visual effects for the Earth and flight patterns were produced by Whiskytree, for disappearing infrastructure by Identity FX, and for the three-dimensional text tracking by Legion Studios.[5] According to Terwilliger, the visual effects required people in creative and technical fields to form a perfectly shaped Earth, as a photorealistic Earth is subjective.[27] The last shot of Earth features lights of flight patterns from FlightAware as seen on July 24, 2014.[28]

Because the film was shot digitally, it had to be transferred to 15/70 and 65/70mm celluloid prints by RPG Productions and FotoKem, respectively,[5] for IMAX purposes.[29] Cinelicious did the telecine and restoration of the 16mm format.[5] Terwilliger wanted an A-list narrator and score composer for the film, and wanted the narrator to have experience with aviation. Harrison Ford, who is also a pilot, recognized Terwilliger from One Six Right and accepted his offer to narrate the film, which was done over three days in early 2014. Ford narrated the entire rough cut of the film, watching it five times to "get into the character".[2][3]

Themes and style

Living in the Age of Airplanes contains themes of human migration, globalization, and the history of aviation.[30] The film is self-described as "a visual journey about how far we've come and how fast we got there".[31] According to Seginus Aerospace, the film's theme is connection because it shows how people and objects may travel more easily and quickly using aviation; according to the narration; "Everywhere we go, we find pieces of everywhere else".[32] Philip Cosand, a volunteer critic and former projectionist at the Pacific Science Center IMAX, said the film's main theme is perspective because its main point is to shift audiences from a negative view of aviation to a positive one, and to broaden audiences with a technical view. He said it has very few technical points, as does the IMAX documentary To Fly! (1976).[33] Blake Snow of Paste summarizes the film's moral as commercial aviation having "enhanced human life, especially [their] adventurous spirit"; although the industry is imperfect, it deserves one's perspective and gratitude.[34]

Visually stylistic choices drive the film forward.[35] It has been categorized as a travelogue documentary by various critics.[36] Terwilliger said some shots have metaphorical meanings; for example, a shot of a tree in Africa represents the continent as the film's heart.[10] Paul Thompson, writing for TravelPulse, said "Perspective" is a reference to sitting in an aircraft's window seat; "There are so many awful, divisive things going on in our world right now, that flying seven miles over it all is quite a wonderful escape sometimes".[37]

Release

The first trailer for Living in the Age of Airplanes was premiered on July 19, 2014, under the initial release title Aviation: The Invisible Highway, at the 2014 Global Business Travel Association convention.[38] It was later released on YouTube on July 29.[39] Two months prior, test screenings were conducted, gaining generally positive responses.[40] On December 12, it was announced the title had been changed to Living in the Age of Airplanes and its release date was confirmed.[41] National Geographic Films acquired the rights to the film on December 15; president of distribution Mark Katz said t is on par with their "mission to inspire, illuminate and teach".[42] The film's YouTube channel released two of its trailers on December 16, 2014, and April 3, 2015; the second trailer is shorter and has excerpts of Ford's narration, while the first is adapted from the Invisible Highway trailer,[q] with texts and shots unused in the film, and the song "Outro" by M83.[31][43] The poster was unveiled on March 7, 2015,[44] with the tagline; "A mile of runway can take you anywhere".[45]

Living in the Age of Airplanes premiered on April 6, 2015, on an exclusive Emirates Airbus A380 flight with the flight number 1400, which took off from Los Angeles International Airport, flew over Hollywood, circled over the Pacific Ocean, and landed at the same airport.[47] GE Aviation was among the invitation senders,[48] and the film's social media team did a sweepstake.[49] Following a press conference at the airport's Emirates Lounge,[46] attendees, including aviation enthusiasts, museum staff, and media, were able to watch it on the aircraft's entertainment screens[50] as well as interview Terwilliger and Horner; Ford was unable to attend after being injured in a plane crash,[45] which National Geographic reported created more interest in the film.[51] Terwilliger also clarified that Emirates did not sponsor the film.[3] Harriet Baskas of USA Today praised the premiere, calling it "fun and appropriate",[1] and Mikey Glazer of TheWrap called it the "coolest movie premiere ever".[46] Living in the Age of Airplanes then premiered theatrically at the Lockheed Martin IMAX Theater[52] at the National Air and Space Museum on April 8.[53] Terwilliger chose the venue in remembrance of watching To Fly! there. The film was played three times a day until 2016.[4] Premiere attendees included Congressional staff, NASA personnel, as well as members of other federal agencies.[54]

It was later released on April 10 in IMAX, Omnimax, digital, and museum theaters[23][55][56] throughout the United States and Canada,[57] beginning with 15 venues.[23] Whether or not an IMAX documentary film gets screened is up to individual theaters; thus, the film's team rely on the general public to contact their nearest appropriate theater in order to expand screening venues.[58] In Montreal's Canadian Museum of History, the film was translated to French. retitled Vivre À L'ère des Avions.[59] It was supported by Aéroports de Montréal, and a used French dub track by Guy Nadon.[60] The Robert Zemeckis Center for Digital Arts' screened the film free-of-charge for students of USC School of Cinematic Arts.[61] It was also screened for attendees of the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh.[62] The film also played in Franz Josef, Vilnius, and Valletta.[63] Screening continues long after; in December 2, 2017, the TCL Chinese Theater screened the film and hosted a question-and-answer session with Terwilliger.[64]

On September 14, 2016, National Geographic released Living in the Age of Airplanes on DVD and Blu-ray formats. The releases include a small booklet with a scene guide,[29] which includes an online password to three of the film's Easter eggs as well as a preview of One Six Right.[65] Special features include three aviation B-rolls, a deleted scene set in Hawaii, five behind-the-scenes videos, a video of the Emirates premiere, and the second trailer. Possibly due to product placement, there are nine videos by Airbus, GE Aviation, and FedEx that tour their works.[29] Terwilliger Productions also released the film on their website, including access to the special features.[66] The film was also released for streaming on iTunes and YouTube Movies; Juice Distribution distributed it on the latter,[67][68] and the special features were also accessible via iTunes.[69]

Reception

Box office

In Australia, Living in the Age of Airplanes earned US$7,787 at the IMAX at Melbourne Museum (first released February 3, 2017), and in the United Kingdom, it earned US$224 at the BFI IMAX (first released October 15, 2015); thus earning a total of US$8,011 according to The Numbers. These were as of March 6, 2017 and 23 October, 2015, respectively. The film appeared on several charts, gaining 17th place at "All Time Worldwide Box Office for National Geographic Entertainment Movies". Meanwhile as of October 30, 2016, 15,359 Blu-rays were sold in the United States, earning US$460,460 and reaching number 13 on the daily sales chart. Overall, DVD sales earned US$241,093 and Blu-ray sales earned US$1,476,672, for a total of US$1,717,765, according to The Numbers.[57]

Critical response

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Rotten Tomatoes | 57% (seven reviews)[70] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Blu-ray.com | |

| Common Sense Media | |

| High-Def Digest | |

| Quad-City Times | |

| Times Colonist | |

| The Seattle Times | |

Film critics were polarized on the contents of Living in the Age of Airplanes; many praised it as a celebratory and insightful look at aviation[75][76][77] while others panned it as an publicity stunt of the industry,[75][78][79] although Snow thought that is not a bad thing.[34] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a 57% score with an average rating of 7.1/10, based on seven critic reviews.[70] The film drew praise from voice actor Roger Craig Smith, journalists Jon Ostrower and Amelia Rose Earhart, personality Jason Silva, and Jason Rabinowitz, host of Flightradar24's podcast AvTalk.[80] The film was also endorsed by prominent figures in the aviation industry,[40][81] and was used in a 2018 event in collaboration with several United States airlines in response to the decline in the number of pilots.[82]

Several critics thought it succeeds in showing the difficulty of life pre-aviation and the subtle impacts of aviation, making it an overall emotional experience;[36] Paula Fleri-Soler of the Times of Malta called it "An ode to planes".[77] Its ending was praised as a tearjerker.[35][36][83] Tiffany Lafleur of The Concordian noted the flawless transition between topics with no fillers and recommended it for documentary fans.[76] The quality of Ford's narration received polarizing opinions; some reviewers called it stiff and overblown,[45][73] though it was also labeled awe-inspiring[75] and personal.[71] Michael D. Reid of the Times Colonist credited much of the film's success to Ford, calling the line "The airplane is the closest thing we've ever had to a time machine" the most powerful of the film.[73] Aviation publications said Living in the Age of Airplanes will most like appeal to a wide audience rather than a niche aviation community,[28][48][50] though Fleri-Soler opined otherwise.[77] Some critics stressed the importance of viewing the film without judgment on aviation, "for only with a blank canvas can one truly appreciate the significance of this film".[69]

Other critics were dismayed by the film's lack or omission of historical content and the disadvantages of aviation such as being a major contributor to climate change.[74][79] "The World Comes to Us" shies away from topics of capitalism and underpaid labor when depicting shipping.[79] The uncertainty over the future of aviation is also not covered, though John Hartl of The Seattle Times called the film "modest" and a "nearly seamless, [...] sunny depiction of what to expect and [has] been accomplished".[74] Frank Scheck of The Hollywood Reporter argued that it "doesn't shy away from pointing out the many inconveniences suffered along the way".[75] Cosand said criticisms of the film not being technical enough are invalid; he recommends the IMAX documentary Legends of Flight (2010) for those who seek technical information.[33] Sandie Angulo Chen of Common Sense Media criticized Ford's narration for "accusing" travelers of not enjoying flights without mentioning the root of the problem.[72] Jonathan Turner of The Dispatch-Argus said the film's purpose is not to educate about aviation but is rather a "love letter to flight".[83] Some critics lamented the film's short running time.[84][71]

The cinematography received more praise. Luke Hickman of High-Def Digest said the film blurs the line between digital and film, with some shots appearing illusionary.[29] Chen recommended it as an add-on to a museum admission, especially for aviation enthusiasts, citing its rich visuals and educational value.[72] They were compared to Rocky Mountain Express (2011),[33] Planet Earth (2006),[29] and the book The World is Flat (1976).[45] The visuals were said to represent a love of aviation,[84] thus enhancing Ford's narration.[75] Some said the visuals alone makes the film worth paying for.[37][72] Horner's score received universal acclaim for its ambiance and rich tone;[75][36][83][85] Hickman said it is better than most film scores.[29] While it was said to be "a bit schmaltzy", it has a spirited tone.[86] The score was considered a good representation of Horner's style but its relative brevity compared to his other works was noted.[87] Ronnie Scheib of Variety and Daniel Eagan of Film Journal International, however, panned the score as excessive.[78][79] The film's 7.1 surround sound design was praised for its clarity, nuance, and balance.[29][71]

Terwilliger's response to criticism

Terwilliger responded to audiences who criticized Living in the Age of Airplanes for not being similar to One Six Right, stating the core audiences are not them and that he felt One Six Right portrays general aviation as it should, leaving no need for a follow-up. He stated the criticism was expected and that some One Six Right fans expressed awe at the difference between One Six Right and Living in the Age of Airplanes.[19]

In a 2016 interview with Tom Hudson of James Horner Film Music, also in response to Horner's death in a plane crash shortly after the film's release, Terwilliger said:[6]

The issues [in aviation] are in the news: they are talked about, they do get their screen time. [This film] is meant to take the things we don't think about and put them front-and-center. The advertisement ... is, 'It's a beautiful thing that we're living in the age of airplanes'. It's a celebration of that. It makes no excuses. It's not a propaganda film. It's not a Wright brothers film ... we don't mention any of the milestones of aviation. It's very big, ... 35,000-f[ee]t view of aviation.

[T]he tragedy is incalculable, and the loss, for sure. It doesn't change aviation for me, in terms of my love of it, in terms of the message in the film. [I]s it perfect? No. Is there some risk? Yes. Is there more risk in small planes and [private flying than in big planes and commercial flying? Yeah. Those facts haven't changed, and it's very unfortunate, but it doesn't impact my love or enthusiasm at all for it. Ever since I was a kid, I think it's a beautiful thing.

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giant Screen Cinema Association Achievement Awards | September 10, 2015 | Best Original Score | James Horner | Won | [88] |

| Big Idea | National Geographic Studios[t] | Won | |||

| North American Film Awards | 2016 | Best Score | James Horner | Won | [89] |

See also

- Winged Migration (2001), a documentary also shot on all seven continents

Notes

- ^ Specifically at Egypt (Cairo, Luxor); Kenya (Amboseli National Park, Nairobi, Naivasha)

- ^ Specifically at Union Glacier and the South Pole

- ^ Specifically at Cambodia (Siem Reap); China (Hong Kong); Maldives (Kurendhoo, Malé)

- ^ Specifically at England (London); France (Paris, Toulouse); Italy (Rome, Venice); the Netherlands (Aalsmeer, Amsterdam)

- ^ Specifically at Canada (Vancouver); Mexico (Chichen Itza and Tulum); St. Marteen (Maho Beach)

- ^ Specifically at Australia (Sydney, Uluru)

- ^ Specifically at Argentina (Foz do Iguaçu, Puerto Iguazú, Ushuaia); Chile (Easter Island, Punta Arenas); Costa Rica (Monteverde, Varablanca)

- ^ Specifically at Anchorage, Denali National Park, Port Alsworth, and Talkeetna

- ^ Specifically at Grand Canyon West

- ^ Specifically at Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Mojave Desert

- ^ Specifically at Hilo, Honolulu, Kona, Maui, Oahu, and Waikiki

- ^ Specifically at Las Vegas

- ^ Specifically at Durham

- ^ Specifically at Memphis International Airport

- ^ Specifically at Monument Valley and Zion National Park

- ^ No specific year given.

- ^ The Invisible Highway trailer opens with highlighting the film's scale and the originality of the shots; this is removed in the Living in the Age of Airplanes trailer. While the former says "In 2015 comes a documentary", the latter says "Now comes a documentary".

- ^ Movie:

Video quality:

Audio quality:

Special features:

- ^ Story:

Video quality:

Audio quality:

Special features:

- ^ Awarded "for its outreach to the aviation community to promote the film".

References

- ^ a b Baskas, Harriet (April 7, 2015). "A380 hosts in-flight premier for 'Living in the Age of Airplanes'". USA Today. Gannett. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Terwilliger, Brian J. (April 13, 2015). "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Air & Space/Smithsonian (Interview). Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Terwilliger, Brian J. (September 10, 2016). "LIVING IN THE AGE OF AIRPLANES: Story Behind The Movie – Brian J. Terwilliger [FULL INTERVIEW]" (YouTube video). Interviewed by Film Courage. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Tallman, Jill W. (April 9, 2015). "'Living in the Age of Airplanes' Premieres at Air and Space Museum". Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Noted in the film's credits.

- ^ a b Terwilliger, Brian J. (September 10, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes: Interview with Brian Terwilliger". James Horner Film Music (Interview). Interviewed by Hudson, Tom. Los Angeles. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Terwilliger, Brian J. (October 26, 2016). "LRM Exclusive Interview: Documentary Director Brian J. Terwilliger for LIVING IN THE AGE OF AIRPLANES". Latino Review Media (Interview). Interviewed by Patta, Gig. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Terwilliger, Brian J. (September 5, 2014). "Filmmaker Brian J. Terwilliger Talks About ONE SIX RIGHT, A Film for Pilots and Flying Enthusiasts" (YouTube video). Interviewed by Film Courage. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Living in the Age of Airplanes: Production Notes" (PDF). 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Walker, Julie Summers; Terwilliger, Brian J. (August 15, 2015). "Unlocking the world". Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Terwilliger, Brian J. (March 21, 2016). "The first giant screen film to span seven continents encapsulates the incredible power of flight" (Interview). Interviewed by Moffitt, Kelly. St. Louis: KWMU-FM. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Waruszewski, Andrew (November 17, 2016). "Cinematographer Mastered Complex Logistics of Global Flight Documentary". Variety (Interview). Interviewed by Valentini, Valentina I. Penske Media. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Terwilliger, Brian J. (April 9, 2015). "Exclusive interview with Brian Terwilliger | Living in the Age of Airplanes | Emirates Airline" (YouTube video). Emirates. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Behind-the-Scenes: Hunts Mesa Time-lapse (Facebook video). Living in the Age of Airplanes. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes: Seeing Aviation for the First Time (Blu-ray). National Geographic Films. 2016.

- ^ As seen from a shot in the film featuring the flight path.

- ^ As depicted in the film.

- ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes: Making of the Alaska House (Blu-ray). National Geographic Films. 2016.

- ^ a b Terwilliger, Brian J. (April 7, 2018). "Episode 017 | Brian Terwilliger | One Six Right | Living In The Age of Airplanes". Podcasting On A Plane (Podcast). Interviewed by Brandon. Google Podcasts. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Behind the scenes: Just a minor issue trying to get a beauty shot on location in #sanfrancisco #goldengatebridge #airplanesmovie (Facebook video). Living in the Age of Airplanes. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Ho, Erica (April 7, 2015). "Review: National Geographic's 'Living in the Age of Airplanes' Is Pure Travel Porn". Map Happy. CafeMedia. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Intrada Records. August 23, 2017. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c Terwilliger, Brian J.; Horner, James (April 9, 2015). "LIVING IN THE AGE OF AIRPLANES Interviews: Brian Terwilliger and James Horner" (YouTube video). Interviewed by Freund, Andrew. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Jean-Baptiste (July 27, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes: Analysis of the Excerpts". James Horner Film Music. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Horner, James (September 14, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Terwilliger Productions. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021 – via Apple Music.

- ^ Horner, James (August 23, 2017). "Living in the Age of Airplanes (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) [Audio CD]". Amazon. Manufactured by Intrada Records. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes: Impossible Shots: Visual Effects (Blu-ray). National Geographic Films. 2016.

- ^ a b Sclair, Ben (July 25, 2015). "You can help rekindle the magic of airplanes". General Aviation News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hickman, Luke (December 6, 2016). "National Geographic: Living in the Age of Airplanes Blu-ray Review". High-Def Digest. Internet Brands. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes Collections". National Geographic Society. 2015. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Living in the Age of Airplanes Official Trailer #1 (YouTube video). Living in the Age of Airplanes. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes: A Review". Seginus Aerospace. July 31, 2017. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c Cosand, Philip (2015). "Living In The Age Of Airplanes: Exploring Humanity's Place In The World". Pacific Science Center. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Snow, Blake (August 6, 2015). "Off the Grid: 5 Ways Living in The Age of Airplanes Will Make You Rethink Travel". Paste. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

If it sounds like Living in the Age of Airplanes is a glowing endorsement of airlines, consumerism and tourism, it's because it is. And that's not a bad thing, even if you're a minimalist hermit who never travels. The point is: Commercial airplanes have enhanced human life, especially our adventurous spirit. This isn't to say airlines and airports deserve a free pass. But they do deserve our perspective. And however slightly flawed they are, they still merit our gratitude.

- ^ a b Terwilliger, Brian J. (August 22, 2015). "Brian Terwilliger – Living In The Age of Airplanes". AviatorCast (Podcast). Interviewed by Chris. Homer, Alaska: Angle of Attack. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cook, Linda. "'Age of Airplanes' takes you on a fantastic flight". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa: Lee Enterprises. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Thompson, Paul (September 13, 2016). "Is 'Living in the Age of Airplanes' The Most Beautiful Aviation Film Ever?". TravelPulse. Northstar Travel Group. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of [@airplanesmovie] (July 28, 2014). "Producer / Director Brian Terwilliger debuts the official film trailer for 7,000 attendees at #GBTA2014" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Living in the Age of [@airplanesmovie] (July 29, 2014). "@jetcitystar Right now! Check it out! http://bit.ly/1nON5yU" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b "Aviation movie: The Invisible Highway". Airlines. International Air Transport Association. May 22, 2014. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of [@airplanesmovie] (December 11, 2014). "Aviation: The Invisible Highway is now officially, "Living in the Age of Airplanes." @NatGeoMovies will release the film on April 10, 2015" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ "National Geographic Studios to Release Original Film "Living in the Age of Airplanes" to Giant Screen, Digital, IMAX and Museum Cinemas Worldwide". Giant Screen Cinema Association. December 15, 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes Official Trailer #2 — Narrated by Harrison Ford (YouTube video). Living in the Age of Airplanes. April 1, 2015. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of [@airplanesmovie] (March 6, 2015). "Sneak peak of the movie poster – final proof at the printer!" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b c d Glazer, Mikey (April 9, 2015). "Harrison Ford's Aviation Documentary 'Living in the Age of Airplanes' Premieres at 35,000 Feet". TheWrap. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c Living in the Age of Airplanes: In-Flight Premiere (Blu-ray). National Geographic Films. 2016.

- ^ "EK1400 (UAE1400) Emirates Flight Tracking and History". FlightAware. April 3, 2015. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Thurber, Matt (April 10, 2015). "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes [@airplanesmovie] (March 29, 2015). "Enter our sweepstakes for your chance to win tickets to the world premiere! We'll be giving away a pair of tickets every day, Sunday through Wednesday, this week. Good luck! #airplanesmovie". Archived from the original on April 12, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2021 – via Instagram.

- ^ a b Funk, Tiffany (April 9, 2015). "Review: Living In The Age Of Airplanes". One Mile at a Time. PointsPros. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Laime, Samantha (March 20, 2015). "Harrison Ford on flying: After crash, he will narrate documentary on flight". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ ""Living in the Age of Airplanes" Soars to the Giant Screen at the National Air and Space Museum April 10" (Press release). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. April 2, 2015. SI-140-2015. Archived from the original on March 31, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

Tickets for Living in the Age of Airplanes are available at the Lockheed Martin Theater box office or online at www.si.edu/imax.

- ^ Bunish, Christine; Galas, Marjorie (October 28, 2016). Rossi, Mimi (ed.). "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Creative Content Wire. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ Greenstone, Adam F. (March 25, 2015). "Determination Regarding Attendance by NASA Employees at the National Geographic Screening and Reception on April 8, 2015" (PDF). Letter to Alternate Designated Agency Ethics Official. Washington, D.C.: NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Longbella, Maren (October 1, 2018). "Soar with new Omnitheater movie about flight". Twin Cities of St. Paul Pioneer Press. Digital First Media. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Planetarium Shows & Showtimes: Living in the Age of Airplanes". Cradle of Aviation Museum. February 11, 2020. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Living in the Age of Airplanes (2015) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Living in the Age of Airplanes. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Vivre à l'ère des avions 4K" [Living in the Age of Airplanes 4K] (in French). Musée canadien de l'histoire. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "LIVING IN THE AGE OF AIRPLANES Opens October 30 at the Science Centre's IMAX(R) TELUS Theatre" (Press release). Montreal: Marketwired. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021 – via GlobeNewswire.

- ^ "Living In The Age Of Airplanes – Presented by the Giant Screen Cinema Association – followed by Q&A with director Brian Terwilliger". Los Angeles: USC School of Cinematic Arts. March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Ford Shoots for the Stars at 2015 EAA AirVenture Oshkosh" (Press release). Dearborn, Michigan: Ford Motor Company. July 8, 2015. Archived from the original on July 6, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via AviationPros.

Ford Presents the "Fly-In Theater". [...] Each evening ... thousands of patrons will watch free movies: ... The 2015 lineup includes ... Living in the Age of Airplanes.

- ^ "Find a Theatre". Living in the Age of Airplanes. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Living in the Age of [@airplanesmovie] (November 17, 2017). "If you live near Los Angeles, don't miss your one chance to see the film in @IMAX at the Chinese Theatre! December 2nd, 11:30 am. Includes Q&A with Director. TIX: http://airplanesmovie.com/tcl" (Tweet). Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Hidden Content". Living in the Age of Airplanes. Archived from the original on February 25, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Terwilliger Productions VHX. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Provided by Terwilliger Productions. iTunes. 2015. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Living in the Age of Airplanes (Motion picture). Distributed locally by Juice Distribution. YouTube Movies. November 30, 2016 [2015]. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b Zupp, Owen (September 14, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes. More Than a Movie". Australian Aviation. Momentum Media. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Liebman, Martin (September 14, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Chen, Sandie Angulo (April 14, 2015). "Living in the Age of Airplanes – Movie Review". Common Sense Media. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Reid, Michael D. (June 19, 2016). "Airplane documentary flies high on Imax". Times Colonist. Glacier Media. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hartl, John (May 28, 2015). "'Living in the Age of Airplanes' stays on an upbeat course". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Scheck, Frank (April 8, 2015). "'Living in the Age of Airplanes': Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. MRC. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Lafleur, Tiffany (November 17, 2015). "Explore how flight changed the world in IMAX". The Concordian. Montreal: Concordia University. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c Fleri-Soler, Paul (June 21, 2015). "An ode to planes". Times of Malta. Allied Newspapers. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Scheib, Ronnie (April 9, 2015). "Film Review: 'Living in the Age of Airplanes'". Variety. Penske Media. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Eagan, Daniel (April 8, 2015). "Film Review: Living in the Age of Airplanes". Film Journal International. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Film". Living in the Age of Airplanes. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Spohr, Carsten (June 7, 2021). "The fascination for flying is unchanged" (Interview). Interviewed by Newton, Graham. International Air Transport Association. Archived from the original on June 10, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

One element of safeguarding our future is to show that we are proud of aviation. This has been the most difficult time for the industry since the second world war, wherever you are in the world. But people's fascination with flying has not suffered. [...] In this regard, I urge people to watch the movie, Living in the Age of Airplanes again.

- ^ McIntosh, Andrew (August 22, 2018). "Facing pilot shortages, Delta and Horizon Air look to the next generation of aviation enthusiasts". Puget Sound Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c Turner, Jonathan (October 13, 2016). "'Airplanes' documentary a soaring tribute to travel". The Dispatch-Argus. Davenport, Iowa: Lee Enterprises. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Thompson, Paul (March 26, 2015). Brown, David Parker (ed.). ""Living in the Age of Airplanes" Is a Visually-Stunning Aviation Film for All Ages". Airline Reporter. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ^ Dale, Jillian (September 13, 2016). "Living In The Age of Airplanes Film Review – Narration by Harrison Ford". HuffPost. BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ Southall, James (September 21, 2016). "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Movie Wave. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Hanssen, Nils Jacob Holt (August 3, 2018). Haga, Thor Joachim (ed.). "Living in the Age of Airplanes (James Horner)". Celluloid Tunes (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "Living in the Age of Airplanes". Giant Screen Cinema Association. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ We're honored to have been bestowed "Best Score" at the North American Film Awards. If you haven't already heard James Horner's magical score, you can listen to samples from all tracks here: www.airplanesmovie.com/soundtrack (Twitter video). Living in the Age of Airplanes. November 3, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

External links

- Official website

- Living in the Age of Airplanes at IMDb

- Sensory-friendly screenplay by the Science Museum of Minnesota (archived at the Wayback Machine)

- Living in the Age of Airplanes at Metacritic

- Archive of the Aviation: The Invisible Highway website at the Wayback Machine