Army of the Mughal Empire

| Mughal Army ارتش مغول | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Mughal Empire | |

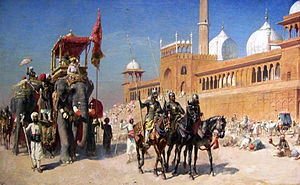

Arrival of an imperial procession of the emperor Farrukh Siyar at Delhi's "world-revealing" mosque on a Friday, to hear the sermon (khutba) recited in his name | |

| Founded | c. 1556 |

| Disbanded | c. 1806 |

| Leadership | |

| Former Military | Timurid Army |

| Padishah (Great Emperor) | Mughal Emperor |

| Grand-Vizier | Mughal Vazere'azam |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 15-25 years |

The Army of the Mughal Empire was the force by which the Mughal emperors established their empire in the 15th century and expanded it to its greatest extent at the beginning of the 18th century. Although its origins, like the Mughals themselves, were in the cavalry-based armies of central Asia, its essential form and structure was established by the empire's third emperor, Akbar.

The army had no regimental structure and the soldiers were not directly recruited by the emperor. Instead, individuals, such as nobles or local leaders, would recruit their own troops, referred to as a mansab, and contribute them to the army.

History

List of conflicts involving the Mughals:

- Conquest of Babur (1504-1528)

- Mughal–Rajput Wars (1526–1779)

- Mughal–Afghan Wars (1526–1752)

- conquest of Malwa (1560–1570)

- Conquest of Bengal sultanate in Tukaroi & Rajmahal(1575-1576)

- Mughal–Persian Wars (1605–1739)

- Mughal–Ahom Wars (1616–1682)

- Mughal–Sikh Wars (1621–1783)

- Second Mughal–Safavid War (1622–1623)

- First Mughal–Safavid War (1649–1653)

- Conquest_of_Chittagong (1665–1666)

- Gokula Singh rebellion (1670)

- Mughal–Tibet Wars (1679–1684)

- Mughal–Portuguese War (1692–1693)

- Mughal–Maratha Wars (1680–1707)

- Mughal–East India Company Wars (1686–1857)

- Mughal Civil Wars (1627–1720)

- Nader Shah's invasion of India (1738–1740)

The Mughals originated in Central Asia. Like many Central Asian armies, the mughal army of Babur was horse-oriented. The ranks and pay of the officers were based on the horses they retained. Babur's army was small and inherited the Timurid military traditions of central Asia.[1] It would be wrong to assume that Babur introduced a gunpowder warfare system, because mounted archery remained the vital part of his army.[2] Babur's empire did not last long and the mughal empire collapsed with the expulsion of Humayun, and the mughal empire founded by Akbar in 1556 proved more stable and enduring.[3] Akbar restructured the army and introduced a new system called the mansabdari system. Therefore, the essential structure of the Mughal army started from the reign of Akbar.

Mughal emperors maintained a small standing army. They numbered only in thousands. Instead the officers called mansabdars provided much of the troops.

Organization

The Mughal Emperors maintained small standing armies. The emperor's own house hold troops were called Ahadis. They were directly recruited by the Mughal emperor himself, mainly from the emperor's own blood relatives and tribesmen. They had their own pay roll and pay master, and were better paid than normal horsemen sowars. They were gentlemen soldiers, some of them normally in administrative duties in the palace.

The theoretical potential manpower of Mughal empire in 1647 according to Kaushik Roy from Jadavpur University, could reached 911,400 cavalry and infantry. However, Kaushik Roy also quoted the accumulation the imperial revenue of 12,071,876,840 dams has been calculated by Streissand who translated that the Mughal empire military could support about 342,696 cavalry and 4,039,097 infantry in total.[4]

The Walashahis or imperial bodyguards were regarded as the most trusted and faithful part of the troops, being directly in the pay of the Emperor. They were chiefly, if not entirely, men who had been attached to the Emperor from his youth and had served him while he was only a prince and were thus marked out in a special manner as his personal attendants and household troops.[5]

The emperor also maintained a division of foot soldiers and had his own artillery brigade.

-

Imperial court guards of Shah Jahan

-

Guards of Akbar Shah II during the Durbar procession accompanied by the British Governor Charles Metcalfe

-

Great Mogul And His Court Returning From The Great Mosque At Delhi by Edwin Lord Weeks

-

Head of the Wala-Shahis, Khan-i Dauran

Mansabdars

Akbar introduced this unique system. The Mughal army had no regimental structure. In this system, a military officer worked for the government who was responsible for recruiting and maintaining his quota of horsemen. His rank was based on the horsemen he provided, which ranged from 10(the lowest), up to 5000. A prince had the rank of 25000. This was called the zat and sowar system.

An officer had to keep men and horses in a ratio of 1:2. The horses had to be carefully verified and branded, and Arabian horses were preferred. The officer also had to maintain his quota of horses, elephants and cots for transportation, as well as foot soldiers and artillery. Soldiers were given the option to be paid either in monthly/annual payments or jagir, but many chose jagir. The emperor also allocated jagir to mansabdars for maintenance of the mansabs.

Branches

There were four branches of the Mughal army: the cavalry (Aswaran), the infantry (Paidgan), the artillery (Topkhana) and the navy. These were not divisions with their own commanders, instead they were branches or classes that were distributed individually amongst the Mansabdars, each of whom had some of each of these divisions. The exception to this rule was the artillery, which was a specialized corps with its own designated commander, and was not part of the mansabdari troops.[6] The cavalry held the primary role in the army, while the others were auxiliary.

Cavalry

The cavalry was the most superior branch of the Mughal army. By the reign of Aurangzeb, the Mughal army was mainly composed of Indian Muslims.[7] experts such as Irfan Habib generally agreed that Mughal cavalry are invincible in Indian subcontinent.[8] The superiority of their heavy cavalry discipline and shock charge were a staple of Mughal cavalry.[9][10]

The Barha tribe of Indian Muslims traditionally composed the vanguard of the imperial army, which they held the hereditary right to lead in every battle.[11][12] The horsemen normally recruited by mansabdars were high-class people and were better paid than foot soldiers and artillerymen. They had to possess at least two of their own horses and good equipment. The regular horseman was called a sowar. Normally they used swords, lances, shields, more rarely guns. Their armour was made up of steel or leather, and they wore the traditional dress of their tribes. Mughal armour was not as heavy as Europe, due to the heat, but was heavier than the south Indian outfits.[13] The armour consisted of two layers; the first consisting of steel plates and helmets to secure the head, breast, and limbs. Underneath this steel network of armour was worn an upper garment of cotton or linen quilted thick enough to resist a sword or a bullet, which came down as far as the knees. Silken pants as the lower garment and a pair of kashmir shawls wrapped around the waist completed this costume. There was a habit of covering the body in protective garments until little beyond a man's eyes could be seen.[14]

Adapted to fighting pitched battles in the northern Indian plains,[15] the Mughals were frontal-combat oriented, and shock-charge tactics of the heavy cavalry armed with swords and lances was popular in Mughal armies.[16][17] In times of crisis at battle, the Muslim Mughals would perform a type of fighting called Utara,[18] the act of dismounting from their horses and fighting on foot until they were killed rather than ride away and escape with their lives.[19]

Well-bred horses were either imported from Arabia, Iran or Central Asia, or bred in Sindh, Rajasthan and parts of Punjab. Emperors at times also issued firman or imperial mandates on regular intervals addressing officials like mansabdars, kotwals, zamindars and mutasaddis for the remission of taxes for promoting the horse trade.[20][21]

Camels and Elephants

Mughal cavalry also included war elephants, normally used by generals. They bore well ornamented and good armour. Mainly they were used for transportation to carry heavy goods. Some of the Rajput mansabdar's also provided camel cavalry. They were men from desert areas like Rajasthan. A special elephant unit called Gajnal were carrying Indian swivel-gun mounted on its back.[22][23] two of these kind of light artillery could be carried by single elephant.[22] The Zamburaks or camel units with mounted swivel guns were though as Mughal innovation, as were first mentioned by Bernier, who reports that Aurangzeb took two to three hundred camel- guns with him on his expedition to Kashmir.[24] Its mobility compared to their Gajnal Elephant counterpart were considered pivotal, as those weapons which size are double of normal musket could be shot on top of the camels.[24]

The key to Mughal power in India was its use of warhorses and also its control of the supply of superior warhorses from Central Asia. This was confirmed by victories in the Battle of Panipat, the Battle of Machhiwara, Battle of Dharmatpur, and in eyewitness accounts such as Father Monserrate, which primarily featured the use of traditional Turko-Mongol horse archer tactics rather than gunpowder.[25] Cavalry warfare came to replace the logistically difficult elephant warfare and chaotic mass infantry tactics. Rajputs were co-opted by converting them into cavalry despite their traditions of fighting on foot. This was similar to the Marathas' service to the Deccan Sultanates.[25]

Infantry

The infantry was recruited either by Mansabdars, or by the emperor himself. The emperor's own infantry was called Ahsam. They were normally ill-paid and ill-equipped, and also lacked discipline.[26] This group included bandukchi or gun bearers, swordsmen, as well as servants and artisans.[26] They used a wide variety of weapons like swords, shields, lances, clubs, pistols, rifles, muskets, etc. They normally wore no armour.[26] Unlike the Europeans who placed Wagon forts in their rear formations, the Mughals army placing their wagon in front of enemy centers with.[26] Chains connected the wagons to each other to impeded enemy cavalry charges. This wagon forts provided cover for the slow-loading of the Indian rifles.[26] while also protected Heavy cavalry who positioned behind the direct-fire infantry protected.[26]

Banduqchis

The Banduqchis were the musketmen in the infantry. They formed the bulk of the Mughal infantry.[27] Locally recruited and equipped with matchlocks, bows and spears, the infantry was held in low status and was virtually equated with litter bearers, woodworkers, cotton carders in the army payrolls. Their matchlocks were thrice as slow as the mounted archers. Chronicles hardly mention them in battle accounts.[28] Indian Muslims usually enlisted in the cavalry and seldom recruited in the infantry, looking down at fighting with muskets with contempt. The Banduqchis were mainly made up of Hindus of various castes who were known for their skills as gunmen, such as the Bundelas, the Karnatakas and the men of Buxar.[29][30][31][32][33]

Shamsherbaz

The main infantry was supplemented by specialized units such as the Shamsherbaz. Meaning "sword-wielders" or "gladiators", the Shamsherbaz were elite heavy infantry companies of highly skilled swordsmen. As their name implies, a few of them were assigned to the court to serve as palace guards, or participate in mock-battles of exhibitions of skill. However, tens of thousands of them were assigned to army units by the Mansabdars around the Mughal Empire.[34] The Shamsherbaz were frequently used in siege warfare, where they would be unleashed to deal with the resistance once the walls were breached with explosives or artillery.[35] Much of the Shamsherbaz were recruited from religious sects such as Sufi orders.[36]

Artillery

The artillery was a specialized corps with its own designated commander, the Mir-i-Atish.[37] The office of Mir-i-Atish grew in importance during the time of the later Mughals.[38] Being in charge of the defense of the Imperial Palace Fort and being in personal contact with the Emperor, the Mir-i-Atish commander great influence.[39] Mughal artillery consisted of heavy cannons, light artillery, grenadiers and raketies. Heavy cannons were very expensive and heavy for transportation, and had to be dragged by elephants into the battlefield. They were somewhat risky to be used in the battlefield, since they exploded sometimes, killing the crew members. Light artillery was the most useful in the battle field. They were mainly made up of bronze and drawn by horses. This also included swivel guns born by camels called zamburak. They were very effective on the battlefield.

-

Mughal Archers early 17th century

-

Mughal Zamburakchi

-

Mughal-era Cannon

Navy

The Empire did maintain a fleet of warships and transport ships. The Mughal warships were characterized their strength and their size, due to the shipbuilding skills of their Bengalis shipbuilder.[40] The Navy's main duty was controlling piracy, sometimes used in war.[41] It is known from the standard survey of maritime technology in 1958, that the Bengalis expertize on shipbuilding were duplicated by The British East India Company in the 1760s, which leading to significant improvements in seaworthiness and navigation for European ships during the Industrial Revolution.[42]

The foundation of salt water naval force of the Mughal empire were established by Akbar from late 16th century after he conquered Bengal and Gujarat.[43] Emperor Akbar reorganized the imperial navy from a collections of civilian vessels with more professional institutions of Naval administration which is detailed in the Ain-i-Akbari, the annals of Akbar's reign.It identifies the navy's primary objectives including the maintenance of transport and combat vessels, the retention of skilled seamen, protection of civilian commerce and the enforcement of tolls and tariffs.[43] About 20 years after the Siege of Hooghly, the Mughals in Bengal came into a conflict , known as the Anglo-Mughal War, with the English East India company under admiral Nicholson, who had been granted permission by the emperor to sail about 10 warships,[44] The objectives of the company was to seize Chittagong and consolidate its interests.[45] However, The English were defeated as the Mughal counterattack under Shaista Khan towards Hooghly proved too much.[45][46]

One of the best-documented naval campaign of the Mughal empire were provided during the conflict against kingdom of Arakan, where in December 1665, Aurangzeb dispatched Shaista Khan, his governor of Bengal to command 288 vessels and more than 20,000 men to pacify the pirate activities within Arakan territory and to capture Chittagong,[43] while also assisted by about 40 Portuguese vessels.[47]: 230 This ensuing conflict in Chittagong were documented as largest Early Modern galley battles fought which nvolved more than 500 ships. and the number of were more than 40,000 bodies.[43]

During the era Aurangzeb, the chronicle of Ahkam 'Alamgiri, reveals how the Mughal empire has struggled to establish strong navy, boldened by the failure to prevent losses of Muslim vessels off the coast of the Maldives islands. Aurangzeb's Vizier, Jafar Khan, blames the Mughal lack of ability to establish an effective navy not due to lack of resources and money, but to the lack of men to direct (the vessels).[48] Thus Syed Hassan Askari concluded that the lack of priority of Aurangzeb to afford his naval project due to his conflicts against the Marathas has hindered him to do so.[48] Andrew de la Garza stated other reason of the Mughal navy did not evolved into a high seas fleet during 17th century was technological inferiority of Indian blast furnaces in comparation with the European counterparts, who capable of generating the temperatures required to manufacture cast iron cannon in quantity.[43] Nevertheless, Syed maintained maintained that Mughal was largely not independent to control the rampart piracy and European naval incursions, and instead resorted to depend on the strength of friendly Arab forces from Muscat to keep the Portuguese in check.[48] According to records in the Mughal invasion on kingdom of Ahom, The characteristic of Ghurab warships of Mughals in Bengal regions were Ghurab warships which were outfitted with 14 guns.[49] the personnels were numbered around 50 to 60 crews.[49] The officers of those ships were conscripted from Dutch, Portuguese, British, and Russian naval officers.[49]

However, Syed Hassan also highlighted that Aurangzeb are not completely neglect it since he has acquired the British expertise to captured the fort of Janjira island, and thus establishing naval cooperation with semi independent Siddi community naval force of Janjira State which resisted the Marathas.[48] It is said in the Ahkam 'Alamgiri record that the commander of British navy, Sir John Child, has concluded peace with the Mughal empire in 1689 due to his fear towards the "Mughal navy" force of Janjira which let by Siddi Yaqub.[48] This Siddi navy has armed with rare huge vessels of certain craft which weighted between 300 and 400 tonnnage with heavy ordnance on row boats, where few matchlock gunner and spear men cramped.[48] The proficiency of the Siddi Yaqub navy are exemplified during Siege of Bombay, where Siddi Yaqub and his Mappila fleet blockaded the fortress and forced the submission of the Britain forces.[50] The naval forces of Janjira state which given subsidy and sponsored by Aurangzeb with the access of Surat port could construct more bigger ships like frigates and Man-of-war[51]: 34 According to Grant Duff, until 1670 the imperial navy under the leadership of Khan Jahan with the Janjira mariners has clashed frequently against Maratha Navy under Shivaji, where the Janjira and Mughal naval forces always comes victorious.[52] Contrary to the naval forces in Bengal which relied mostly on riverine fitted Gharb warships,[51]: 28

Chelas

Chela were slave soldiers in the Mughal army. As a counterpoise to the mercenaries in their employ, over whom they had a very loose hold, commanders were in the habit of getting together, as the kernel of their force, a body of personal dependents or slaves, who had no one to look to except their master. Such troops were known by the Hindi name of chela (a slave). They were fed, clothed, and lodged by their employer, had mostly been brought up and trained by him, and had no other home than his camp. They were recruited chiefly from children taken in war or bought from their parents during times of famine. The great majority were of Hindu origin, but all were made Muslims when received into the body of chelas. These chelas were the only troops on which a man could place entire reliance as being ready to follow his fortunes in both foul and fair weather.[53]

Like the Timurids and other Mongol-derived armies, and unlike other Islamic states, the Mughal empire did not use slave soldiers prominently. Slave soldiers were mainly placed in very lowly positions such as manual labourers, footmen and low-level officers rather than professional elite soldiers like Ghilman, Mamluks or Janissaries. However, eunuch officers were prized for their loyalty.[54]

See also

References

- ^ Rachel Dwyer (2016). Key Concepts in Modern Indian Studies. NYU Press. ISBN 9781479848690.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (3 June 2015). Warfare in Pre-British India - 1500BCE to 1740CE. Routledge. ISBN 9781317586913.

- ^ Sita Ram Goel (1994). The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India.

- ^ Roy, Kaushik (30 March 2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740-1849 (ebook). Taylor & Francis. p. 29. ISBN 9781136790874.

- ^ Zahiruddin Malik (1977). The Reign Of Muhammad Shah 1919-1748. p. 298.

- ^ Abraham Eraly (2007). The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books. p. 291. ISBN 9780143102625.

- ^ Stephen Meredyth Edwardes, Herbert Leonard Offley Garrett (1995). Mughal rule in India. ISBN 9788171565511.

- ^ Hassan, Farhat (2004). State and Locality in Mughal India Power Relations in Western India, C.1572-1730 (Hardcover). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521841191. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

Others suggest that it was not artillery but cavalry that made the Mughals invincible in the

- ^ William Irvine (2007). Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (ed.). Later Mughals. University of Minnesota. p. 669. ISBN 9789693519242. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ John F. Richards (1993). "Part 1, Volume 5". The Mughal Empire (Paperback). Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780521566032. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ William Irvine (1971). Later Mughal. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 202.

- ^ Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research (1975). Journal of the Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research: Volume 12. Rajasthan Institute of Historical Research.

- ^ J.J.L. Gommans (2002). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire 1500-1700. Taylor & Francis. p. 120. ISBN 9781134552764.

- ^ William Irvine (1903). The army of the Indian Moghuls: its organization and administration. p. 64.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520974234.

- ^ Jeremy Black (2001). Beyond the Military Revolution War in the Seventeenth Century World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781350307735.

- ^ Pius Malekandathi (2016). The Indian Ocean in the Making of Early Modern India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351997461.

- ^ Rajesh Kadian (1990). India and Its Army. the University of Michigan. p. 132. ISBN 9788170940494.

- ^ Altaf Alfroid David (1969). Know Your Armed Forces. Army Educational Stores. p. 13.

- ^ Azad Choudhary, R.B. (2017). "The Mughal and the Trading of Horses in India, 1526-1707" (PDF). International Journal of History and Cultural Studies. 3 (1). Hindu College, University of Delhi: 1–18. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Jos J. L. Gommans (2002). Mughal Warfare - Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500-1700. p. 114. ISBN 9780415239899.

- ^ a b Mehta, JL. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India (Paperback). Sterling Publishers Pvt Limited. p. 359. ISBN 9788120710153. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Nossov, Konstantin (2012). War Elephants (ebook). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 9781846038037. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ a b Jos J. L. Gommans (2002). Mughal Warfare Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500-1700 (Paperback). Routledge. pp. 125, 128. ISBN 9780415239899. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

(zamburak, shutarnal, shahin) that was attached to the saddle of the dromedary. These zamburaks were first mentioned by Bernier, who reports that Aurangzeb took two to three hundred camel- guns with him on his expedition to Kashmir

- ^ a b André Wink. The Making of the Indo-Islamic World c.700–1800 CE. University of Wisconsin, Madison: Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d e f Pratyay, Pratyan; D. Spessert JD, Robert D. (2019). "Climate of Conquest War, Environment, and Empire in Mughal North India". Military Review. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ Satish Chandra (January 0101). Medieval India Old NCERT Histroy [sic] Book Series for Civil Services Examination. Mocktime Publications.

- ^ André Wink. The Making of the Indo-Islamic World c.700–1800 CE. University of Wisconsin, Madison: Cambridge University Press. p. 164.

- ^ Satish Chandra (1959). Parties And Politics At The Mughal Court. Oxford University Press. p. 245.

- ^ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1920). The Mughal Administration. p. 17.

musketeers were mostly recruited from certain Hindu tribes , such as the Bundelas , the Karnatakis , and the men of Buxar

- ^ Ghosh, D. K. Ed. (1978). A Comprehensive History Of India Vol. 9. Orient Longmans.

The Indian muslims looked down upon fighting with muskets and prided on sword play. The best gunners in the mughal army were hindus

- ^ William Irvine (2007). Later Muguhals. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 668.

- ^ J.J.L. Gommans (2022). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire 1500-1700. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134552764.

- ^ Garza, Andrew de la (28 April 2016). The Mughal Empire at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500-1605. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-24530-8.

- ^ Andrew de la Garza (2016). The Mughal Empire at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500-1605. Routledge. ISBN 9781317245308.

- ^ Andrew de la Garza (2016). The Mughal Empire at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 9781317245315.

- ^ Abraham Elahy (2007). The Mughal World:Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India. p. 291. ISBN 9780143102625.

- ^ Sandhu (2003). A Military History of Medieval India. Vision Books. p. 657. ISBN 9788170945253.

- ^ V. D. Mahajan (2007). History of Medieval India. Chand. p. 235. ISBN 9788121903646.

- ^ Roy, Atulchandra (1961). "Naval Strategy of the Mughals in Bengal". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 24: 170–175. JSTOR 44140736. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Roy, Atul Chandra (1972). A History of Mughal Navy and Naval Warfares. World Press.

- ^ Kelly, Morgan; Ó Gráda, Cormac (2017). "Technological Dynamism in a Stagnant Sector: Safety at Sea during the Early Industrial Revolution" (PDF). UCD Centre for Economic Research Working Paper Series. UCD SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS UNIVERSITY COLLEGE DUBLIN: 10. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ H. C. Das; Indu Bhusan Kar (1988). Pani, Subas (ed.). Glimpses of History and Culture of Balasore. Orissa State Museum. p. 66. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ a b Temple of India foundation (2018). Bengal – India's Rebellious Spirit (ebook). Notion Press. pp. 449–450. ISBN 9781643247465. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Bhattacharya, Sudip (2014). Unseen Enemy The English, Disease, and Medicine in Colonial Bengal, 1617-1847 (ebook). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443863094. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (2007) [First published 1974]. The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. VII: The Mughal Empire. Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- ^ a b c Nag, Sajal, ed. (2023). The Mughals and the North-East Encounter and Assimilation in Medieval India (Ebook). Manohar. ISBN 9781000905250. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ Veevers, David (2020). The Origins of the British Empire in Asia, 1600-1750 (Hardcover ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 9781108483957. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ Kyd Nairne, Alexander (1988). History of the Konkan (Hardcover). Asian Educational Services. p. 69. ISBN 9788120602755. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Sharma, S. R. (1940). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material. p. 11.

- ^ Bano, Shadab (2006). "MILITARY SLAVES IN MUGHAL INDIA". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 67: 350–57.

![]() This article incorporates text from The army of the Indian Moghuls: its organization and administration, by William Irvine, a publication from 1903, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from The army of the Indian Moghuls: its organization and administration, by William Irvine, a publication from 1903, now in the public domain in the United States.

Further reading

- Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth; Garrett, Herbert Leonard Offley (1930). Mughal Rule in India.

- Sharma, S. R. (1940). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material.