Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Burnside | |

|---|---|

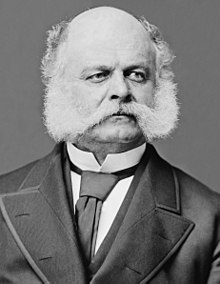

Burnside c. 1880 | |

| United States Senator from Rhode Island | |

| In office March 4, 1875 – September 13, 1881 | |

| Preceded by | William Sprague IV |

| Succeeded by | Nelson W. Aldrich |

| 30th Governor of Rhode Island | |

| In office May 29, 1866 – May 25, 1869 | |

| Lieutenant | William Greene Pardon Stevens |

| Preceded by | James Y. Smith |

| Succeeded by | Seth Padelford |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ambrose Everett Burnside May 23, 1824 Liberty, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | September 13, 1881 (aged 57) Bristol, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Angina |

| Resting place | Swan Point Cemetery Providence, Rhode Island |

| Political party | Democratic (1858–1865) Republican (1866–1881) |

| Spouse |

Mary Richmond Bishop

(m. 1852; died 1876) |

| Education | United States Military Academy |

| Profession | Soldier, inventor, industrialist |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Burn |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States (Union) |

| Branch/service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1847–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Army of the Potomac Army of the Ohio |

| Battles/wars | |

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three-time Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor and industrialist.

He was responsible for some of the earliest victories in the Eastern theater, but was then promoted above his abilities, and is mainly remembered for two disastrous defeats, at Fredericksburg and the Battle of the Crater (Petersburg). Although an inquiry cleared him of blame in the latter case, he never regained credibility as an army commander.

Burnside was a modest and unassuming individual, mindful of his limitations, who had been propelled to high command against his will. He could be described as a genuinely unlucky man, both in battle and in business, where he was robbed of the rights to a successful cavalry firearm that had been his own invention. His spectacular growth of whiskers became known as "sideburns", deriving from the two parts of his surname.

Early life

Burnside was born in Liberty, Indiana, and was the fourth of nine children[1] of Edghill and Pamela (or Pamilia) Brown Burnside, a family of Irish and English origins.[2] His great-great-grandfather Robert Burnside (1725–1775) was born in Scotland and settled in the Province of South Carolina.[3] His father was a native of South Carolina; he was a slave owner who freed his slaves when he relocated to Indiana. Ambrose attended Liberty Seminary as a young boy, but his education was interrupted when his mother died in 1841; he was apprenticed to a local tailor, eventually becoming a partner in the business.[4]

As a young officer before the Civil War, Burnside was engaged to Charlotte "Lottie" Moon, who left him at the altar. When the minister asked if she took him as her husband, Moon is said to have shouted "No siree Bob!" before running out of the church. Moon is best known for her espionage for the Confederacy during the Civil War. Later, Burnside arrested Moon, her younger sister Virginia "Ginnie" Moon, and their mother. He kept them under house arrest for months but never charged them with espionage.[5]

Early military career

He obtained an appointment to the United States Military Academy in 1843 through his father's political connections and his own interest in military affairs. He graduated in 1847, ranking 18th in a class of 47, and was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Artillery. He traveled to Veracruz for the Mexican–American War, but he arrived after hostilities had ceased and performed mostly garrison duty around Mexico City.[6]

At the close of the war, Lt. Burnside served two years on the western frontier under Captain Braxton Bragg in the 3rd U.S. Artillery, a light artillery unit that had been converted to cavalry duty, protecting the Western mail routes through Nevada to California. In August 1849, he was wounded by an arrow in his neck during a skirmish against Apaches in Las Vegas, New Mexico. He was promoted to 1st lieutenant on December 12, 1851.

In 1852, he was assigned to Fort Adams, Newport, Rhode Island, and he married Mary Richmond Bishop of Providence, Rhode Island, on April 27 of that year. The marriage lasted until Mary's death in 1876, but was childless.[7]

In October 1853, Burnside resigned his commission in the United States Army and was appointed commander of the Rhode Island state militia with the rank of major general. He held this position for two years.

After leaving the Regular Army, Burnside devoted his time and energy to the manufacture of a firearm that bears his name: the Burnside carbine. President Buchanan's Secretary of War John B. Floyd contracted the Burnside Arms Company to equip a large portion of the Army with his carbine, mostly cavalry and induced him to establish extensive factories for its manufacture. The Bristol Rifle Works were no sooner complete than another gunmaker allegedly bribed Floyd to break his $100,000 contract with Burnside.[citation needed]

Burnside ran as a Democrat for one of the Congressional seats in Rhode Island in 1858 and was defeated in a landslide. The burdens of the campaign and the destruction by fire of his factory contributed to his financial ruin, and he was forced to assign his firearm patents to others. He then went west in search of employment and became treasurer of the Illinois Central Railroad, where he worked for and became friendly with George B. McClellan, who later became one of his commanding officers.[8] Burnside became familiar with corporate attorney Abraham Lincoln, future president of the United States, during this time period.[9]

Civil War

First Bull Run

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Burnside was a colonel in the Rhode Island Militia. He raised the 1st Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and was appointed its colonel on May 2, 1861.[10] Two companies of this regiment were then armed with Burnside carbines.

Within a month, he ascended to brigade command in the Department of northeast Virginia. He commanded the brigade without distinction at the First Battle of Bull Run in July and took over division command temporarily for wounded Brig. Gen. David Hunter. His 90-day regiment was mustered out of service on August 2; he was promoted to brigadier-general of volunteers on August 6 and was assigned to train provisional brigades in the Army of the Potomac.[6]

North Carolina

Burnside commanded the Coast Division or North Carolina Expeditionary Force from September 1861 until July 1862, three brigades assembled in Annapolis, Maryland, which formed the nucleus for his future IX Corps. He conducted a successful amphibious campaign that closed more than 80% of the North Carolina sea coast to Confederate shipping for the remainder of the war. This included the Battle of Elizabeth City, fought on February 10, 1862, on the Pasquotank River near Elizabeth City, North Carolina.[citation needed]

The participants were vessels of the United States Navy's North Atlantic Blockading Squadron opposed by vessels of the Confederate Navy's Mosquito Fleet; the latter were supported by a shore-based battery of four guns at Cobb's Point (now called Cobb Point) near the southeastern border of the town. The battle was a part of the campaign in North Carolina that was led by Burnside and known as the Burnside Expedition. The result was a Union victory, with Elizabeth City and its nearby waters in their possession and the Confederate fleet captured, sunk, or dispersed.[11]

Burnside was promoted to major general of volunteers on March 18, 1862, in recognition of his successes at the battles of Roanoke Island and New Bern, the first significant Union victories in the Eastern Theater. In July, his forces were transported north to Newport News, Virginia, and became the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac.[6]

Burnside was offered command of the Army of the Potomac following Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's failure in the Peninsula Campaign.[12] He refused this opportunity because of his loyalty to McClellan and the fact that he understood his own lack of military experience, and detached part of his corps in support of Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia in the Northern Virginia Campaign. He received telegrams at this time from Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter which were extremely critical of Pope's abilities as a commander, and he forwarded on to his superiors in concurrence. This episode later played a significant role in Porter's court-martial, in which Burnside appeared as a witness.[13]

Burnside again declined command following Pope's debacle at Second Bull Run.[14]

Antietam

Burnside was given command of the Right Wing of the Army of the Potomac (the I Corps and his own IX Corps) at the start of the Maryland Campaign for the Battle of South Mountain, but McClellan separated the two corps at the Battle of Antietam, placing them on opposite ends of the Union battle line and returning Burnside to command of just the IX Corps. Burnside implicitly refused to give up his authority and acted as though the corps commander was first Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno (killed at South Mountain) and then Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox, funneling orders through them to the corps. This cumbersome arrangement contributed to his slowness in attacking and crossing what is now called Burnside's Bridge on the southern flank of the Union line.[15]

Burnside did not perform an adequate reconnaissance of the area, and he did not take advantage of several easy fording sites out of range of the enemy; his troops were forced into repeated assaults across the narrow bridge, which was dominated by Confederate sharpshooters on the high ground. By noon, McClellan was losing patience. He sent a succession of couriers to motivate Burnside to move forward, ordering one aide, "Tell him if it costs 10,000 men he must go now." He further increased the pressure by sending his inspector general to confront Burnside, who reacted indignantly: "McClellan appears to think I am not trying my best to carry this bridge; you are the third or fourth one who has been to me this morning with similar orders."[16] The IX Corps eventually broke through, but the delay allowed Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill's Confederate division to come up from Harpers Ferry and repulse the Union breakthrough. McClellan refused Burnside's requests for reinforcements, and the battle ended in a tactical stalemate.[17]

Fredericksburg

After McClellan failed to pursue General Robert E. Lee's retreat from Antietam, Lincoln ordered McClellan's removal on November 5, 1862, and selected Burnside to replace him on November 7, 1862. Burnside reluctantly obeyed this order, the third such in his brief career, in part because the courier told him that, if he refused it, the command would go instead to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, whom Burnside disliked. Burnside assumed charge of the Army of the Potomac in a change of command ceremony at the farm of Julia Claggett in New Baltimore, Virginia.[18][19][20] McClellan visited troops to bid them farewell. Columbia Claggett, Julia Claggett's daughter-in-law, testified after the war that a "parade and transfer of the Army to Gen. Burnside took place on our farm in front of our house in a change of command ceremony at New Baltimore, Virginia on November 9, 1862."[21][18]

President Abraham Lincoln pressured Burnside to take aggressive action and approved his plan on November 14 to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. This plan led to a humiliating and costly Union defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13. His advance upon Fredericksburg was rapid, but the attack was delayed when the engineers were slow to marshal pontoon bridges for crossing the Rappahannock River, as well as his own reluctance to deploy portions of his army across fording points. This allowed Gen. Lee to concentrate along Marye's Heights just west of town and easily repulse the Union attacks.

Assaults south of town were also mismanaged, which were supposed to be the main avenue of attack, and initial Union breakthroughs went unsupported. Burnside was upset by the failure of his plan and by the enormous casualties of his repeated, futile frontal assaults, and declared that he would personally lead an assault by the IX corps. His corps commanders talked him out of it, but relations were strained between the general and his subordinates. Accepting full blame, he offered to retire from the U.S. Army, but this was refused. Burnside's detractors labeled him the "Butcher of Fredericksburg".[22]

In January 1863, Burnside launched a second offensive against Lee, but it bogged down in winter rains before anything was accomplished, and has derisively been called the Mud March. In its wake, he asked that several openly insubordinate officers be relieved of duty and court-martialed; he also offered to resign. Lincoln quickly accepted the latter option, and on January 26 replaced Burnside with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, one of the officers who had conspired against him.[23]

East Tennessee

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Burnside offered to resign his commission altogether but Lincoln declined, stating that there could still be a place for him in the army. Thus, he was placed back at the head of the IX Corps and sent to command the Department of the Ohio, encompassing the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois. This was a quiet area with little activity, and the President reasoned that Burnside could not get himself into too much trouble there. However, antiwar sentiment was riding high in the Western states as they had traditionally carried on a great deal of commerce with the South, and there was little in the way of abolitionist sentiment there or a desire to fight for the purpose of ending slavery. Burnside was thoroughly disturbed by this trend and issued a series of orders forbidding "the expression of public sentiments against the war or the Administration" in his department; this finally climaxed with General Order No. 38, which declared that "any person found guilty of treason will be tried by a military tribunal and either imprisoned or banished to enemy lines".

On May 1, 1863, Ohio Congressman Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent opponent of the war, held a large public rally in Mount Vernon, Ohio in which he denounced President Lincoln as a "tyrant" who sought to abolish the Constitution and set up a dictatorship. Burnside had dispatched several agents to the rally who took down notes and brought back their "evidence" to the general, who then declared that it was sufficient grounds to arrest Vallandigham for treason. A military court tried him and found him guilty of violating General Order No. 38, despite his protests that he was simply expressing his opinions in public. Vallandigham was sentenced to imprisonment for the duration of the war and was turned into a martyr by antiwar Democrats. Burnside next turned his attention to Illinois, where the Chicago Times newspaper had been printing antiwar editorials for months. The general dispatched a squadron of troops to the paper's offices and ordered them to cease printing.

Lincoln had not been asked or informed about either Vallandigham's arrest or the closure of the Chicago Times. He remembered the section of General Order No. 38 which declared that offenders would be banished to enemy lines and finally decided that it was a good idea so Vallandigham was freed from jail and sent to Confederate hands. Meanwhile, Lincoln ordered the Chicago Times to be reopened and announced that Burnside had exceeded his authority in both cases. The President then issued a warning that generals were not to arrest civilians or close down newspapers again without the White House's permission.[24]

Burnside also dealt with Confederate raiders such as John Hunt Morgan.

In the Knoxville Campaign, Burnside advanced to Knoxville, Tennessee, first bypassing the Confederate-held Cumberland Gap and ultimately occupying Knoxville unopposed; he then sent troops back to the Cumberland Gap. Confederate commander Brig. Gen. John W. Frazer refused to surrender in the face of two Union brigades but Burnside arrived with a third, forcing the surrender of Frazer and 2,300 Confederates.[25]

Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga, and Burnside was pursued by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, against whose troops he had battled at Marye's Heights. Burnside skillfully outmaneuvered Longstreet at the Battle of Campbell's Station and was able to reach his entrenchments and safety in Knoxville, where he was briefly besieged until the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Fort Sanders outside the city. Tying down Longstreet's corps at Knoxville contributed to Gen. Braxton Bragg's defeat by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Chattanooga. Troops under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman marched to Burnside's aid, but the siege had already been lifted; Longstreet withdrew, eventually returning to Virginia.[23]

Overland Campaign

Burnside was ordered to take the IX Corps back to the Eastern Theater, where he built it up to a strength of over 21,000 in Annapolis, Maryland.[26] The IX Corps fought in the Overland Campaign of May 1864 as an independent command, reporting initially to Grant; his corps was not assigned to the Army of the Potomac because Burnside outranked its commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, who had been a division commander under Burnside at Fredericksburg. This cumbersome arrangement was rectified on May 24 just before the Battle of North Anna, when Burnside agreed to waive his precedence of rank and was placed under Meade's direct command.[27]

Burnside fought at the battles of Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, where he did not perform in a distinguished manner,[28] attacking piecemeal and appearing reluctant to commit his troops to the frontal assaults that characterized these battles. After North Anna and Cold Harbor, he took his place in the siege lines at Petersburg.[29]

The Crater

As the two armies faced the stalemate of trench warfare at Petersburg in July 1864, Burnside agreed to a plan suggested by a regiment of former coal miners in his corps, the 48th Pennsylvania: to dig a mine under a fort named Elliot's Salient in the Confederate entrenchments and ignite explosives there to achieve a surprise breakthrough. The fort was destroyed on July 30 in what is known as the Battle of the Crater. Because of interference from Meade, Burnside was ordered, only hours before the infantry attack, not to use his division of black troops, which had been specially trained for the assault. Instead, he was forced to use untrained white troops. He could not decide which division to choose as a replacement, so he had his three subordinate commanders draw lots.[30]

The division chosen by chance was that commanded by Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie, who failed to brief the men on what was expected of them and was reported during the battle to be getting drunk in a bombproof shelter well behind the lines, providing no leadership. Ledlie's men entered the huge crater instead of going around it, became trapped, and were subjected to heavy fire from Confederates around the rim, resulting in high casualties.[31][32]

Burnside was relieved of command on August 14 and sent on "extended leave" by Grant. He was never recalled to duty for the remainder of the war. A court of inquiry later placed the blame for the Crater fiasco on Burnside and his subordinates. In December, Burnside met with President Lincoln and General Grant about his future. He was contemplating resignation, but Lincoln and Grant requested that he remain in the Army. At the end of the interview, Burnside wrote, "I was not informed of any duty upon which I am to be placed." He finally resigned his commission on April 15, 1865, after Lee's surrender at Appomattox.[33]

The United States Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War later exonerated Burnside and placed the blame for the Union defeat at the Crater on General Meade for requiring the specially trained USCT (United States Colored Troops) men to be withdrawn.[citation needed]

Postbellum career

After his resignation, Burnside was employed in numerous railroad and industrial directorships, including the presidencies of the Cincinnati and Martinsville Railroad, the Indianapolis and Vincennes Railroad, the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad, and the Rhode Island Locomotive Works.[citation needed]

He was elected to three one-year terms as Governor of Rhode Island, serving from May 29, 1866, to May 25, 1869. He was nominated by the Republican Party to be their candidate for governor in March 1866, and Burnside was elected governor in a landslide on April 4, 1866. This began Burnside's political career as a Republican, as he had been a Democrat before the war.[34]

Burnside was a Companion of the Massachusetts Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, a military society of Union officers and their descendants, and served as the Junior Vice Commander of the Massachusetts Commandery in 1869. He was commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) veterans' association from 1871 to 1872, and also served as the Commander of the Department of Rhode Island of the GAR.[35] At its inception in 1871, the National Rifle Association of America chose him as its first president.[36]

During a visit to Europe in 1870, Burnside attempted to mediate between the French and the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War. He was registered at the offices of Drexel, Harjes & Co., Geneva, week ending November 5, 1870.[37] Drexel Harjes was a major lender to the new French government after the war, helping it to repay its massive war reparations.

In 1876 Burnside was elected as commander of the New England Battalion of the Centennial Legion, the title of a collection of 13 militia units from the original 13 states, which participated in the parade in Philadelphia on July 4, 1876, to mark the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.[38]

In 1874 Burnside was elected by the Rhode Island Senate as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, was re-elected in 1880, and served until his death in 1881. Burnside continued his association with the Republican Party, playing a prominent role in military affairs as well as serving as chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee in 1881.[39]

Death and burial

Burnside died suddenly of "neuralgia of the heart" (Angina pectoris) on the morning of September 13, 1881, at his home in Bristol, Rhode Island, accompanied only by his doctor and family servants.[40]

Burnside's body lay in state at City Hall until his funeral on September 16.[41] A procession took his casket, in a hearse drawn by four black horses, to the First Congregational Church for services which were attended by many local dignitaries.[41] Following the services, the procession made it way to Swan Point Cemetery for burial.[41][42][39] Businesses and mills were closed for much of the day, and "thousands" of mourners from "all towns of the state and many places in Massachusetts and Connecticut" crowded the streets of Providence for the occasion.[41]

Assessment and legacy

Personally, Burnside was always very popular, both in the army and in politics. He made friends easily, smiled a lot, and remembered everyone's name. His professional military reputation, however, was less positive, and he was known for being obstinate, unimaginative, and unsuited both intellectually and emotionally for high command.[43] Grant stated that he was "unfitted" for the command of an army and that no one knew this better than Burnside himself. Knowing his capabilities, he twice refused command of the Army of the Potomac, accepting only the third time when the courier told him that otherwise the command would go to Joseph Hooker. Jeffry D. Wert described Burnside's relief after Fredericksburg in a passage that sums up his military career:[44]

He had been the most unfortunate commander of the Army, a general who had been cursed by succeeding its most popular leader and a man who believed he was unfit for the post. His tenure had been marked by bitter animosity among his subordinates and a fearful, if not needless, sacrifice of life. A firm patriot, he lacked the power of personality and will to direct recalcitrant generals. He had been willing to fight the enemy, but the terrible slope before Marye's Heights stands as his legacy.

— Jeffry D. Wert, The Sword of Lincoln

Bruce Catton summarized Burnside:[45]

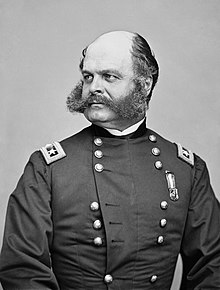

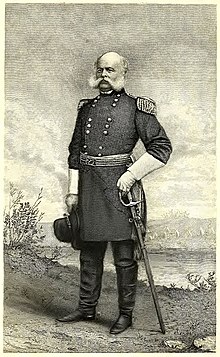

... Burnside had repeatedly demonstrated that it had been a military tragedy to give him a rank higher than colonel. One reason might have been that, with all his deficiencies, Burnside never had any angles of his own to play; he was a simple, honest, loyal soldier, doing his best even if that best was not very good, never scheming or conniving or backbiting. Also, he was modest; in an army many of whose generals were insufferable prima donnas, Burnside never mistook himself for Napoleon. Physically he was impressive: tall, just a little stout, wearing what was probably the most artistic and awe-inspiring set of whiskers in all that bewhiskered Army. He customarily wore a high, bell-crowned felt hat with the brim turned down and a double-breasted, knee-length frock coat, belted at the waist—a costume which, unfortunately, is apt to strike the modern eye as being very much like that of a beefy city cop of the 1880s.

— Bruce Catton, Mr. Lincoln's Army

Sideburns

Burnside was noted for his unusual beard, joining strips of hair in front of his ears to his mustache but with the chin clean-shaven; the word burnsides was coined to describe this style. The syllables were later reversed to give sideburns.[43]

Honors

- In 1866, Allison Township in Lapeer County, Michigan, was renamed Burnside Township to honor Ambrose Burnside.[46]

- An equestrian statue designed by Launt Thompson, a New York sculptor, was dedicated in 1887 at Exchange Place in Providence, facing City Hall.[47] In 1906, the statue was moved to City Hall Park, which was re-dedicated as Burnside Park.[48]

- Bristol, Rhode Island, has a small street named for Burnside.[citation needed]

- The Burnside Memorial Hall in Bristol, Rhode Island, is a two-story Richardson Romanesque public building on Hope Street. It was dedicated in 1883 by President Chester A. Arthur and Governor Augustus O. Bourn. Originally, a statue of Burnside was intended to be the focus of the porch. The architect was Stephen C. Earle.[49]

- Burnside, Kentucky, in south-central Kentucky, is a small town south of Somerset named for the former site of Camp Burnside, near the former Cumberland River town of Point Isabelle.[citation needed]

- New Burnside, Illinois, along the Cairo and Vincennes Railroad, was named after the former general for his role in founding the village through directorship of the new rail line.[citation needed]

- Burnside Residence Hall at the University of Rhode Island in Kingston was opened in 1966.[50]

- Burnside, Wisconsin is named for the general.[51]

Portrayals

- Burnside was portrayed by Alex Hyde-White in Ronald F. Maxwell's 2003 film Gods and Generals, which includes the Battle of Fredericksburg.[citation needed]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals (Union)

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

Citations

- ^ Marvel, p. 3.

- ^ Mierka, np. The original spelling of his middle name was Everts, for Dr. Sylvanus Everts, the physician who delivered him. Ambrose Everts was also the name of Edghill's and Pamela's first child, who died a few months before the future general was born. The name was misspelled as "Everett" during his enrollment at West Point, and he did not correct the record.

- ^ "Free Family History and Genealogy Records — FamilySearch.org". www.familysearch.org. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- ^ Mierka, np., describes the relationship with the tailor as indentured servitude.

- ^ Eggleston, Larry G. (2003). Women in the Civil War : extraordinary stories of soldiers, spies, nurses, doctors, crusaders, and others. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0786414936. OCLC 51580671.

- ^ a b c Eicher, pp. 155–56; Sauers, pp. 327–28; Warner, pp. 57–58; Wilson, np.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 155–56; Mierka, np.; Warner, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 155–56; Mierka, np.; Sauers, pp. 327–28; Warner, pp. 57–58.

- ^ A. Lincoln, a Corporate Attorney and the Illinois Central Railroad. Sandra K. Lueckenhoff, Missouri Law Review, Volume 61, Issue 2 Spring 1996. Accessed March 2021.

- ^ Combined Military Service Record

- ^ Mierka, np.

- ^ Marvel, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Marvel, pp. 209–10.

- ^ Sauers, pp. 327–28; Wilson, np.

- ^ Bailey, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Sears, pp. 264–65.

- ^ Bailey, pp. 126–39.

- ^ a b Department of the Treasury. Office of the First Comptroller (September 5, 1876). "Approved Claim Files from Prince William County, Virginia: Claggett, Julia F, Claim No. 41668". Library of Congress. Southern Claims Commission. p. 35. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Sears, Young Napoleon, pp. 238–41

- ^ "George McClellan - Biography, Civil War & Importance". History.com. June 10, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ Department of the Treasury. Office of the First Comptroller (September 5, 1876). "Approved Claim Files from Prince William County, Virginia: Claggett, Julia F, Claim No. 41668". Library of Congress. Southern Claims Commission. p. 35. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ William Palmer Hopkins, The Seventh Regiment Rhode Island Volunteers in the Civil War 1862–1865. Providence, RI: The Providence Press, 1903, p. 56.

- ^ a b Wilson, np.; Warner, p. 58; Sauers, p. 328.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 596–97. McPherson remarked that Burnside's "political judgment proved no more subtle than his military judgment at Fredericksburg."

- ^ Korn, p. 104.

- ^ Grimsley, p. 245, n. 43.

- ^ Esposito, text for map 120.

- ^ Grimsley, p. 230, describes Burnside's conduct as "inept". Rhea, p. 317: "[Burnside's] failings were so flagrant that the Army talked about them openly. He stumbled badly in the Wilderness and worse still at Spotsylvania."

- ^ Wilson, np.

- ^ Chernow, 2017, pp. 426-428

- ^ Chernow, 2017, pp. 426-429

- ^ Slotkin, 2009, pp. 70, 166, 322

- ^ Wert, pp. 385–86; Mierka, np.; Eicher, pp. 155–56.

- ^ "Rhode Island Republicans nominate Union General Ambrose Burnside for governor". House Divided. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 155–56.

- ^ "Timeline of the NRA". The Washington Post. January 12, 2013. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

1871: The NRA is created to improve the marksmanship of soldiers. The first president, Civil War general Ambrose Burnside, had seen too many Union soldiers who couldn't shoot straight.

- ^ "Americans in London". New York Times, December 14, 1870, p. 6c, last line.

- ^ New York Times March 16, 1876.

- ^ a b Wilson, np.; Eicher, p. 156.

- ^ "General Burnside Dead". The Boston Globe. September 14, 1881. p. 1. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The Lamented Burnside". Fall River, Massachusetts: Fall River Daily Herald. September 17, 1881. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "Civil War Veterans interred at Swan Point Cemetery". Swan Point Cemetery. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Goolrick, p. 29.

- ^ Wert, p. 217.

- ^ Catton, pp. 256–57.

- ^ Romig, Walter (1986) [1973]. Michigan Place Names. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1838-X.

- ^ Raub, Patricia (February 21, 2012). "Burnside: Our Statue But Not Our Hero". The Occupied Providence Journal. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

The monument stood for nearly twenty years in Exchange Place, facing City Hall, with horses, wagons, and carriages moving in all directions around it.

- ^ "Major General Ambrose E. Burnside, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Art Inventories Catalog. The Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Marshall, Philip C. "Hope Street Survey Descriptions". Philip C. Marshall. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

President Chester A. Arthur and Governor Augustus O. Bourn of Bristol dedicated the hall to the memory of General Ambrose E. Burnside (1824-1881), whose statue was intended to be the focus of the porch.

- ^ "URI History and Timeline". University of Rhode Island. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

1966. Aldrich, Burnside, Coddington, Dorr, Ellery, and Hopkins Residence Halls were opened

- ^ Robert E. Gard (September 9, 2015). The Romance of Wisconsin Place Names. Wisconsin Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87020-708-2.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8094-4740-1.

- Catton, Bruce. Mr. Lincoln's Army. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Company, 1951. ISBN 0-385-04310-4.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-487-6.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Goolrick, William K., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Rebels Resurgent: Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4748-7.

- Grimsley, Mark. And Keep Moving On: The Virginia Campaign, May–June 1864. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-2162-2.

- Korn, Jerry, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Fight for Chattanooga: Chickamauga to Missionary Ridge. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0-8094-4816-5.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Marvel, William. Burnside. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8078-1983-2.

- Mierka, Gregg A. "Rhode Island's Own." Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine MOLLUS biography. Accessed July 19, 2010.

- Rhea, Gordon C. The Battles for Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern May 7–12, 1864. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8071-2136-3.

- Sauers, Richard A. "Ambrose Everett Burnside." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0-89919-172-X.

- Slotkin, Richard (2009). No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5883-6848-5.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-2506-6.

- Wilson, James Grant, John Fiske and Stanley L. Klos, eds. "Ambrose Burnside." In Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography. New Work: D. Appleton & Co., 1887–1889 and 1999.

External links

- Mary Richmond Bishop Burnside at History of American Women

- Ambrose E. Burnside in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Burnside's grave Archived May 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Civil War Home biography

- 1824 births

- 1881 deaths

- Ambrose Burnside

- People from Liberty, Indiana

- Republican Party governors of Rhode Island

- Presidents of the National Rifle Association

- People of Rhode Island in the American Civil War

- Union Army generals

- American militia generals

- United States Military Academy alumni

- People of Indiana in the American Civil War

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- Republican Party United States senators from Rhode Island

- Burials at Swan Point Cemetery

- Grand Army of the Republic Commanders-in-Chief

- 19th-century American politicians

- Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations