Saint-Eustache, Paris

| Saint-Eustache, Paris | |

|---|---|

Saint-Eustache from the south east | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 2 Impasse Saint-Eustache, 1er arr. |

| State | France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°51′48″N 2°20′42″E / 48.86333°N 2.34500°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | French Gothic, French Renaissance, French classical |

| Groundbreaking | 1532 |

| Completed | 1633 |

| Direction of façade | West |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Church of St. Eustache, Paris (Template:Lang-fr), is a church in the 1st arrondissement of Paris. The present building was built between 1532 and 1632.

Situated near the site of Paris' medieval marketplace (Les Halles) and rue Montorgueil, Saint-Eustache exemplifies a mixture of multiple architectural styles: its structure is Flamboyant Gothic[1] while its interior decoration[2] and other details are Renaissance and classical.

The 2019 Easter Mass at Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris was relocated to Saint-Eustache after the Notre-Dame de Paris fire.

History

Situated in Les Halles, an area of Paris once home to the country's largest food market, the origins of Saint Eustache date back to the 13th century. A modest chapel was built in 1213, dedicated to Saint Agnes, a Roman martyr.[3] The small chapel was funded by Jean Alais, a merchant at Les Halles who was granted the rights to collect a tax on the sale of fish baskets as repayment of a loan he gave to King Philippe-Auguste.[4] The church became the parish church of the Les Halles area in 1223 and was renamed Saint-Eustache in 1303.[5]

The name of the church refers to Saint Eustace, a Roman general of the second century AD. He was a passionate hunter; his conversion followed a vision he had of a crucifix in the horns of a deer he was hunting, He was martyred, along with his family, for converting to Christianity. He is now the patron saint of hunters.[6] The church was renamed for Saint Eustache after receiving relics related to the Roman martyr as donations from the Abbey of Saint Denis.[7]

As the area prospered, the church became too small for its congregation; the church wardens decided to build a larger building. Construction of the current church began in 1532, during the reign of François I and continued until 1632, and in 1637, it was consecrated by Jean-François de Gondi, Archbishop of Paris.

Although the architects are unknown, similarities to designs used in the extension of the church of Saint-Maclou in Pontoise (begun in 1525) point to Jean Delamarre and/or Pierre Lemercier, who collaborated in that work.[8] The Italian-born architect Domenico da Cortona has also been suggested.[9]

The project [10] Some of the architects associated with the church's construction include Pierre Lemercier,[11] his son Nicolas Lemercier,[12] and Nicolas' son-in-law Charles David.[13]

-

Facade project by Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (16th century - not built)

-

The facade in the 17th century

-

The church in 1739

-

Funeral of Mirabeau April 4, 1791, during the French Revolution

The building was not entirely finished until 1640. Construction was slowed by the difficult site, a shortage of funds, and the French Wars of Religion. The addition of two chapels in 1655 severely compromised the structural integrity of the church, necessitating the demolition of the facade, which was rebuilt in 1754 under the direction of the architect Jean Mansart de Jouy.[14]

Many celebrated Parisians are connected with the Church of St. Eustache. Louis XIV made his First Communion there in 1649.[15] Cardinal Richelieu, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson (Madame de Pompadour), and Molière were all baptized there; Molière was also married there in 1662.[16] Mozart held his mother's funeral there.[17] Funerals were held at St. Eustache for Queen Anne of Austria and the military hero Turenne. Marie de Gournay, an early advocate of equal rights for women, was buried there in 1645.[18]

During the French Revolution, the church was, like most churches in Paris, desecrated and looted. It was closed to Catholic worship in 1793 and used for a time as the "Temple of Agriculture", a storage place for food supplies.[19] It was used for the funeral of the revolutionary leader Mirabeau, on April 4, 1791,it was re-opened in 1795 with significant damage to the building and its furniture.[20] It was not formally returned to the church until 1803.[21]

The building was further damaged by a fire in 1844, and was restored by Victor Baltard.[22][23] Baltard directed a complete restoration of the building from 1846 to 1854, including the construction of the organ case, pulpit, and high altar and the repair of the church's paintings.[24] The church was set afire during the Semaine sanglante, the last battle of Paris Commune in May 1871, necessitating repairs to the attic, buttresses, and south facade.[25][26] The facade was modified in 1928–1929.[27]

In 1969, the Halles de Paris market was relocated to Rungis, considerably modifying the neighborhood of the Church of St. Eustache.[28] Les Halles became a shopping center and hub for regional transportation, and the Church of St. Eustache remains a landmark of the area and a functioning church.[29]

Exterior

-

The classical west facade (left), the traditional entrance, with its unfinished tower

-

The South facade, with the transept in center

-

Detail of the south transept and sundial, with sculpture of deer with crucifix at top

-

The apse, or east end of the cathedral

The exterior of the church presents a mixture of Flamboyant Gothic, classical, and Renaissance elements. The Gothic exterior elements are the elaborate flying buttresses, which receive the downward and outward thrust from the rib vaults in the interior. The most Gothic portion is the apse at the east end, where the buttresses surround semicircular group of chapels, located behind the altar. The classical elements dominate the principal facade, which is unfinished, and different from the rest of the exterior. It is decorated with pairs of ionic columns with paired sets of Doric columns on the lower level, and Ionic columns on the upper level. The south portals primarily decorated in the Renaissance style, with a profusion of ornamental sculpture in the form of foliage and seashells. At the top of the pointed arch is a sculpture of a deer with a crucifix in its horns, depicting the vision of Saint Eustache.[30]

Interior

-

Plan of the interior

-

The nave and choir viewed from the western entrance

-

Nave facing west, organ, pulpit (left) and banc d'ouvre (right)

-

Vault of the choir, with a hanging keystone

Nave, transept and collateral aisles

The church is relatively short in length at 105m, but its interior is 33.45m high to the vaulting.[31] The interior is given unity by the imposing verticality of its pillars and arches. The Flamboyant Gothic elements are primarily in the vaulted ceilings decorated with a network of ornamental ribs and hanging keystones.

Below are the Renaissance elements, in the form of pillars and pilasters representing the classical orders of architecture, rounded arcades, and walls covered with elaborate decorative sculpture of seraphim and bouquets of flowers. The columns and pillars which support the vaults, following the Renaissance style, have Doric decoration on the lowest level, Ionic decorations on the columns above, and Corinthian decoration on the highest columns.[32]

The nave is flanked by two collateral aisles, which give access to series of small chapels, each abundantly decorated with paintings and sculpture.

Pulpit and Banc d'oeuvre

One of the notable classical features of the nave is the Banc-oeuvre, a group of seats covered a Grecian portico and very ornate carvings. It was the seating reserved for the members of the lay committee which oversaw the finances of the church. Iy was made in 1720 by sculptor Pierre Lepautre, and is crowned by a statue representing "The Triumph of Saint Agnes".[33]

-

A blend of Renaissance classicism (the Corinthian column capitals) and Gothic (the vaults)

-

Banc d'oeuvre of the cathedral, the seating area for the lay committee that oversees the church finances, by Pierre Lepautre. (1720)

-

Detail of "The Triumph of Saint Agnes" on the Banc d'oeuvre (1720)

-

The pulpit

Chapel of the Virgin

-

The Chapel of the Virgin

-

Left panel: "The Virgin of the star sailors"

-

"Central panel: "The triumphant Virgin adored by angels"

-

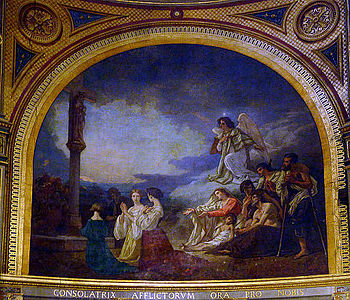

Right panel: "The Virgin comforting the afflicted"

The Chapel of the Virgin, located behind the choir in the apse at the east of the church, was built in 1640 and restored from 1801 to 1804. It was inaugurated by Pius VII on 22 December 1804 when he came to Paris for the coronation of Napoleon.[34]

The apse chapel is topped by a ribbed cul-de-four vault. Its central feature is a sculpture of the Virgin and Child by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle. In the 19th century he painter Thomas Couture complemented the statue with three large paintings illustrating "The Virgin Triumphant, adored by angels"; "The Virgin, a star guiding the sailors"; and "The Virgin, Giving Consolation to he Afflicted." Couture rejected symbolism and idealisation, and used a distinctive realism to the portray the pain of those suffering.[35]

Chapel of Colbert

-

Figure of Jean Baptiste Colbert, by Antoine Coysevox

-

Tomb of Colbert, by Antoine Coysevox

-

Figure of "Fidelity" by Coysevox from the Tomb of Colbert

The chapel next to the Chapel of the Virgin contains the tomb of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Minister of State of Louis XIV and a church warden of Saint-Eustache. The centrepiece is the sculpture of Colbert, made by Antoine Coysevox following drawings by Charles Le Brun, on an ornate tomb made of white and black marble and bronze. Colbert is depicted in prayer, giving Coysevox the opportunity to show his skill in creating the illusion of drapery in stone. Other works of sculpture in the tomb depict "Fidelity" (also by Coysevox) and "Piety" by Jean Baptiste Tuby.[36]

Chapel of Saint Madeleine

The central work in this chapel, "The Ecstasy of Saint Madeleine", was made by Rutilio Manetti in the early 17th century, in a style where the drapery emphasizes the contrasts between darkness and light.

Chapel of Saint-Vincent de Paul

This chapel contains a modern work by the American sculptor Keith Haring (1958-1990), a triptych in bronze with a patina of white gold. Showing the ascent of Christ into heaven, it also includes a humorous figure, "The Radiant Baby", a characteristic of his work.[37]

Chapel of Saint-Genevieve

The major work in this chapel is "Tobias and the Angel", a mannerist painting from the late 16th century by the Tuscan Santi di Tito (1536-1603). It portrays the biblical journey by Tobias, seeking a remedy for the illness of his father. An angel helps him catch a fish which turns out to contain the remedy which heals his father.

Chapel des Charcutiers (Chapel of the Pork Butchers)

As a marketplace church, St. Eustache represented not only its individual parishioners but trade groups as well. The Corporation des Charcutiers, which acts as the pork butchers' professional body, has been a significant patron of the church since the 17th century, and the group's special relationship with the church is represented in the Chapel des Charcutiers.[38] This chapel contains pork butchery depicted in stained glass as well as a contemporary work by John Armleder.[39]

Chapel of the Pilgrims of Emmaüs

The centerpiece of this chapel is a work by Raymond Mason called "The Departure of the Fruits and Vegetables". It depicts, in a humorous way, a procession of merchants carrying fruits and vegetables from the Les Halles markets that formerly were located across the street from the church.

Paintings

-

Peter Paul Rubens, "The disciples of Emmaus" (1611)

-

Martyrdom of Saint Eustache, by Simon Vouet (1635)

-

"Tobias and Angel" by Santi di Tito (1575)

-

Saint John the Baptist by Francois Lemoyne (1726)

The best-known painting in St. Eustache is "The Disciples of Emmaus" by Rubens. The chapel of St. Madeleine holds "Ecstasy of the Madeleine" by Manetti.[40]

The painting of "Saint John the Baptist" by Francois Lemoyne, painted in 1726, depicts the Saint in relaxed, almost sensual pose, with a lamb in a garden, a predecessor of the Rococo works of Charles-Joseph Natoire and François Boucher later in the mid-18th century.

The painting Tobias and the Angel (1575) by the Florentine artist Santi di Tito displays the characterics of late Mannerism or Proto-Baroque school, particularly the elongated figures, the light colors of the palette, and the precocious attitudes of the figures.[41]

Decorative Art

Much of the art and decoration is closely into the architure, such as the bas-relief medallions with carvings of the martyrdom of Saint Cecelia decorating the nave. Some is more contemporary. The L'écoute sculpture by Henri de Miller appears outside the church, to the south. A colourful sculpture in the nave depicts the delivery of produce to market of Les Halles in the 19th century, with the church in the background.

-

Bas-relief of the martyrdom of Saint Cecile

-

Sculpture in the chapel of the Crucifixion

-

Sculpture of the delivery of produce in the Market of Les Halles

Stained glass

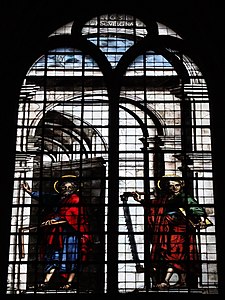

The earliest windows are from the 17th century, and are largely the work of Antoine Soulignac, a master Paris glass artist. His windows are mostly found in the choir. They include a window in the choir depicting of Saint Jerome and Saint Ambroise in an architectural setting (1631). During that period the objective of stained glass in the clair-etage was to admit as much light as possible, so much of the windows were composed of white glass.

-

Clair-etage of the choir, Saint Philip and Saint Matthew, by Antoine Soulignac (1631)

-

Saint Jerome and Saint Ambroise, by Antoine Soulignac, choir (1631)

-

Saint Thomas and Saint Simon, by Antoine Soulignac, choir (17th c.)

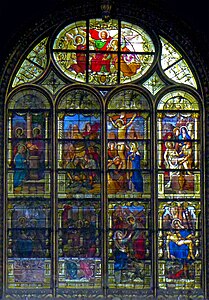

Most of the stained glass is relatively recent, from the 19th and 20th centuries, and features glass painted with silver stain, allowing more realistic drawing, similar to oil paintings, The rose window of the north transept dates to the 19th century.

The various tradesmen who worked in Les Halles, the city market across from the church, contributed to the church's art works. One of the most interesting windows is found in the chapel funded by the society of French charcuterie, the guild of pork butchers, in 1945. It features their coat of arms, depicting three sausages and a pig, with a figure of Saint Antoine, patron saint of the butchers, wearing a white apron, presenting a platter of delicacies.

-

Education of Louis IX, St. Louis Chapel (19th century)

-

"The Crucifixion" South transept (19th century)

-

Rose window of the north transept (19th century)

-

"The Nativity", south transept (19th c.)

-

"The Annunciation", north transept (19th c.)

-

Window donated by the society of French charcuterie, chapel of pork butchers

Organ

With nearly 8,000 pipes, the great organ, with 101 stops and 147 ranks of pipes, is one of the largest organs in France, competing for first place with the great organ of Notre Dame de Paris, with 115 stops and 156 ranks of pipes, and that of Saint Sulpice, with 102 stops and 135 ranks of pipes,[42] and reaching first place with its size, 10 metres wide and 18 metres high. The organ, originally constructed by P.-A. Ducroquet, was powerful enough for the premiere of Hector Berlioz's titanic Te Deum to be performed at St-Eustache in 1855. It was later modified under the direction of Joseph Bonnet. The present organ of St. Eustache was designed by Jean-Louis Coignet under the direction of Titular Organist Jean Guillou and dates from 1989, when it was almost entirely rebuilt by Dutch firm van Den Heuvel, retaining a few ranks of pipes from the former organ and the wooden case, which is original. Each summer, organ concerts commemorate the premieres of Berlioz’s Te Deum and Liszt’s Christus here in 1886.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notable tombs

- Scaramouche (Tiberio Fiorelli), Italian comic actor

- Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Finance Minister

- Jean-Philippe Rameau, Composer

- Susan Feilding, Countess of Denbigh, English courtier

- Anna Maria Mozart, mother of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- François Cureau de La Chambre, physician of Queen Maria Theresa

Access

| Located near the Métro station: Les Halles. |

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 20

- ^ "Patrimoine artistique - Eglise Saint Eustache". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Paroisse Saint-Eustache - Histoire et Patrimoine". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Saint-Eustache". www.nicolaslefloch.fr. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 20

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 18

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Ayers 2004, p. 52.

- ^ Fletcher, Banister and Palmes, J. C. A History of Architecture Charles Scribner's Sons, 1975. ISBN 0-684-14207-4, p. 908

- ^ "Paroisse Saint-Eustache - Histoire et Patrimoine". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building, Volume II. New York: Macmillan. p. 738.

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building, Volume II. New York: Macmillan. p. 739.

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building, Volume I. New York: Macmillan. p. 749.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Goldsby, Robert W. (2012-04-01). Molière on Stage: What's So Funny?. Anthem Press. ISBN 9780857289421.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ "Marie DE GOURNAY : Biographie, Tombe, Citations, Forum... - JeSuisMort.com". JeSuisMort.com (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 18

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 18

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 18

- ^ "Saint-Eustache". www.nicolaslefloch.fr. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Saint-Eustache". www.nicolaslefloch.fr. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Rungis Market over time - Rungis Market". Rungis Market. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ "Histoire de l'église". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-16.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 20

- ^ "Patrimoine artistique - Eglise Saint Eustache". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 21

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 21

- ^ "Patrimoine artistique - Eglise Saint Eustache". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 21

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 21

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 22

- ^ "The Sausage Stained Glass of the Eglise Saint Eustache". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ "Patrimoine artistique - Eglise Saint Eustache". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ "Patrimoine artistique - Eglise Saint Eustache". Eglise Saint Eustache (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ Dumoulin, Ardisson, Maingard and Antonello, Églises de Paris (2010), p. 212

- ^ Le grand orgue, description in French at https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89glise_Saint-Eustache_de_Paris#Le_grand_orgue

Sources

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart: Axel Menges. ISBN 9783930698967.

- A.-M. Sankovitch, The Church of Saint-Eustache in the Early French Renaissance (= Architectura Moderna, 12), Turnhout, 2015 (ISBN 978-2-503-55514-0)

Sources (in French)

- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1