George XII of Georgia

| George XII

გიორგი XII | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Kartli and Kakheti | |

| Reign | 11 January 1798 – 28 December 1800 |

| Coronation | 5 December 1799 (Anchiskhati) |

| Predecessor | Heraclius II |

| Born | 10 November 1746 Telavi, Kingdom of Kakheti, Afsharid Iran |

| Died | 28 December 1800 (aged 54) Tbilisi, Kingdom of Kartli and Kakheti |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Ketevan Andronikashvili Mariam Tsitsishvili |

| Issue among others... | David Bagrat |

| Dynasty | Bagrationi |

| Father | Heraclius II |

| Mother | Anna Abashidze |

| Religion | Georgian Orthodox Church |

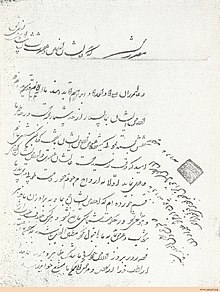

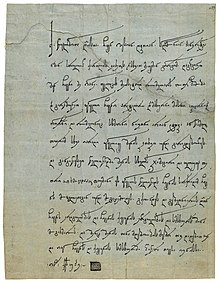

| Khelrtva |  |

George XII (Georgian: გიორგი XII, romanized: giorgi XII), sometimes known as George XIII (November 10, 1746 – December 28, 1800), of the House of Bagrationi, was the second and last King of the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1798 until his death in 1800.

Third son of King Heraclius II, he was raised in a country at war, facing regular attacks from the Persian and Ottoman empires in its south, and constant Lezgin raids from its northeast, and became heir to the throne after the early death of his two older brothers. As prince, he was a diligent governor of royal domains, seeking to repopulate devastated regions in Georgian Armenia, while seating on his father's royal council, assisting him in leading Georgian forces against Ottoman incursions, and representing him in diplomatic negotiations to bring peace to Western Georgia. However, he had to face the ambitions of his step-mother Queen Darejan and her sons, ambitions that would grow into open tensions and a 1794 deal in which King Heraclius changed the law of succession to make George's younger brothers next in line after George.

Taking over after his father's death in 1798, he sought closer relations with Russia as a guarantee to secure his succession, especially after reverting the 1794 deal and appointing his son David as crown prince. This led to a civil war, with the king's younger brothers rebelling, and Russia dispatching troops in 1799 to restore peace in Kartl-Kakheti. An astute diplomat, he also sought alliances with Persia and the Ottoman Empire and was proposed a military partnership by Napoleon, but was forced to use Russia's power to prevent further devastations of his kingdom by his southern neighbors.

Weakened by illness, he was considered a failed monarch, paralyzed by paranoia, who could not put an end to the constant rebellions of his brothers. The poor economic state of the country led to a collapse in bureaucracy and a rise in crime, while he failed to implement any of the major public, financial, and educational reforms his son Ioane proposed. Supporting his kingdom's integration into the Russian Empire, he trusted Russian diplomats without realizing their own role in dividing Georgian nobility. In 1800, he secured from Emperor Paul I an approval of what his "Petitionary Articles", which provided for Eastern Georgia's integration into Russia as an autonomous kingdom, although he died without knowing about its ratification. His death opened the doors for Russia to break its agreements and fully annex Georgia.

Biography

Youth

George Bagrationi was born on October 9, 1746, son of King Heraclius II of Kakheti and his second wife, Queen Ana (herself a daughter of the influential prince Zaal Abashidze). He was the royal couple's fourth child, his elders being princes Vakhtang and Solomon and Princess Rusudan, the latter having died in her childhood. George grew up during a tumultuous time that saw the slow unification of Eastern Georgian states, his father ruling over Kakheti and his grandfather Teimuraz II leading the Kingdom of Kartli.[1] He was raised at the royal court, in the shadow of his half-brother Vakhtang, who was appointed Duke of Aragvi by their father at 9 years old.[2]

His youth was marked by several family tragedies. Queen Ana died in December 1749 when George was only 3. Vakhtang, the presumptive heir of Heraclius II and considered by many to be the hope for a Georgian reunification, died in February 1756.[2] His second brother Solomon died in 1765.

In 1762, shortly after the death of King Teimuraz II, Heraclius II proclaimed the unification of the Georgian states east of the Likhi Range and was crowned King of Kartl-Kakheti in Mtskheta. A young George and the royal family lived from then on in the new capital, Tbilisi, while the Prince Castle of Telavi was rebuilt by the king.[3]

Heir

With the death of Prince Solomon in 1765, George became the oldest surviving son of the royal family and thus, the presumptive heir to his father's crown. One year later, Heraclius II decided to formalize the future of his dynasty, following the failure of Prince Paata Bagrationi of Mukhrani's rebellion.[4] Seeking more responsibility within the country, George asked for the governorship of the Armenian province of Pambak, where he launched a program of repopulation of the region, devastated by centuries of invasion.[5]

George was officially named Heir to the Throne of Two Georgias in 1766. As an apanage, he received large swaths of territories in southern Georgia, at the border with neighboring Persia and largely populated by Armenians and Turkmens, as well as the title of "Lord of Ksani, Tianeti, Aghja-Qala, Lore, and Pambak". This secured George's position as his step-mother, Queen Darejan, increased her influence within the royal court in favor of her own children.[6] One of them, Prince Levan, received the title of Duke of Aragvi, a major domain in the center of Georgia.[2]

This distribution, which continued later with the granting of the Duchy of Ksani to Prince Iulon in 1790, was an attempt to diminish the large powers of the nobility and to centralize the influence of the Bagrationi royal dynasty. With several governors appointed to replace deposed princes, George married in 1766 the young princess Ketevan Andronikashvili, daughter of the Governor of Kiziqi, at the time 12 years old. She soon became popular at the royal court, notably after taking charge herself of a 300-strong army to defeat a Lezgin raid in 1777.[7] The princely couple gave birth to six sons and six daughters before Ketevan's death on June 3, 1782. On July 13, 1783, George remarried to Princess Mariam Tsitsishvili, daughter of Governor George Tsitsishvili of Pambak and Shuragali.

As heir to the throne, George's status within the court was important. He became a member of the Great Council of State, responsible for advising the king in national decision-making.[8] Both this power and his numerous children contributed to increasing an obvious jealousy from his step-mother.[9]

Energetic Prince

As heir, Prince Georgia increasingly became involved in the country's national affairs. In April 1770, he joined his father's forces against the Ottomans and recaptured Akhaltsikhe. Leading an army of 7,000 men, reinforced by a Russian battalion of 1,200 mercenaries, he sought to capture the Atskuri Fortress in the Borjomi Valley, following which the Russian forces left the expedition and left the Georgian troops facing the Turkish invaders alone.[10] Heraclius II and George managed to defeat the Ottomans in Akhalkalaki and Khertvisi, before delivering a decisive victory in Aspindza on April 20. During that battle, George led the left flank of the Georgian army.[11]

Shortly after the Aspindza victory, George and Patriarch Anton I are sent to Imereti in May 1770 to negotiate a peace between King Solomon I and the influential princes Katsia II Dadiani and Simon II Gurieli. Their goal was to form a united Georgian front against a probable Ottoman invasion.[12]

The same year, he was sent by his father to put an end to the noble rebellion in Ksani, along with his half-brother Levan.[13] After this campaign, during which George was made responsible for the detachment of Higher Kartli, the two princes captured the rebellious leader George of Ksani and annexed his domains to the royal territories.[14] In 1777, George of Ksani, pardoned by the king and restored in his duchy, revolted once more and Heraclius sent his two sons once more to defeat him.[7] A brief siege of the Siata Fortress led to a victory by the royal princes and George of Ksani was imprisoned in Tbilisi, while Prince George received as gift the Ksani lands.[7]

On January 1, 1774, King Heraclius II introduced a mandatory military draft throughout the kingdom.[7] To lead by example, George joined the service and was garrisoned in Ghartis-Kari, a border fortress facing constant Lezgin raids.[15] In 1779, he followed his father to besiege Yerevan, whose sovereign Hoseyn Ali Khan had rebelled against Kartl-Kakheti. Chronicler Papuna Orbeliani would describe his "exemplary bravery" and his defeat of the khan in single combat.[15]

Crises

During that time, George saw the status of his brothers rise.[16] As early as 1772, Heraclius II sent the younger prince Levan to Saint Petersburg at the head of a delegation asking for Russia's protection of Georgia against the Ottoman Empire, a responsibility traditionally bestowed upon the heir to the throne.[17] Levan died, however, in 1782 and on July 24, 1783, the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti and the Russian Empire signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, placing Georgia under Russian protectorate and formally recognizing Prince George as heir to the throne.[18]

As Heraclius II grew older and weaker, his influence at the royal court was replaced by that of Queen Darejan. In 1790, Iulon, her oldest son since the death of Levan, was made Duke of Ksani. A year later, Darejan's sons received a donation of 6,000 peasant households, against only 4,000 for George.[19] Finally, in 1794, Heraclius II signed a decree changing the rule of succession that had been in place since the creation of the Kingdom of Georgia in 1010 to install the concept of agnatic seniority, making Prince Iulon second in the line of succession.[19] This decree remains one of the most controversial decisions of Heraclius II, but contemporary sources reveal that the king's signature on the document may have been forced. A royal letter addressed to Prince George dated May 1794 said:[20]

I was forced to sign the decree confirming the grants we gave to your brothers. But it was elaborated without my accord and written by someone who did not have the authority to do so, making it inadmissible. Believe me, on my father Teimuraz's memory, and believe God that I do not give my accord to this decree. No cause nay lead to deny you of your right of birth.

The decree is nonetheless never cancelled by the King,[19] who spent his last years fearing the outcomes of his pro-Russian orientation. In September 1795, the Persian army invaded Kartl-Kakheti and defeated the small Georgian forces at the Battle of Krtsanisi,[21] which ended in a humiliating defeat for Heraclius II, who saw his capital Tbilisi burned down and pillaged.[22] George, in charge of the Kakhetian contingent, was blamed for the loss as he failed to reach Tbilisi in time, held back by his troops' hunger and disease[23] in Sighnaghi.[24]

George was nonetheless forgiven by his father after the battle and tasked with reconquering the capital. In the summer of 1796, George and his Kakhetian soldiers, aided by Russian colonel Sirikhnev and his forces, retook Tbilisi and chased down the Persian garrison.[24] The prince was then charged with rebuilding the capital, while Heraclius II moved to Telavi.[25] In Tbilisi, Prince George rebuilt the main bridge of the city and organized the repopulation of the capital, while using his diplomatic skills to avoid a Lezgin-Ottoman invasion.[26]

In December, George took on the regency of the kingdom as his father became too weak to govern. On December 7, to preserve the family unity, he signed an act recognizing his younger brother Iulon as his heir.[27] The king died on January 12, 1798, at 77 years old,[28] at the Telavi Palace, recently rebuilt by George.[29]

Weak King

Accession

On his deathbed, Heraclius II had George returned from Tbilisi to formally hand him over the state's affairs. On January 14, 1798, two days after his father's death and on the Day of St. Nino,[30] George was recognized King of Kartl-Kakheti by the nobility and the Georgian Orthodox Church in a ceremony in the town of Kazakh.[30] His title showcased his father's ambitions toward unifying the South Caucasus:

Sovereign and Hereditary Prince, the Most Serene King George, by the Will of Our Lord, King of Kartli, King of Kakheti, Hereditary Lord of Samtskhe, Prince of Kazakh, Borchalo, Shamshadilo, Qaq, Shaki and Shirvan, Prince and Lord of Ganja and Yerevan.

King George is stylized George XII, though Russian historian Nikolai Dubrovyn claims he has often been called George XIII during his reign because of King George XI's two reigns.[31]

It's only on December 5, 1799, nearly two years after his accession to the throne but only a few months after his recognition as king by Russian Emperor Paul I,[32] that King George XII's coronation takes place at the Anchiskhati Cathedral in Tbilisi. This coronation, the last in Georgian history, was led by Patriarch Anton II. Russia participated in the ceremony by making the king a Knight of the Order of Saint Andrew and his wife, Queen Mariam, as a First Class Lady of the Order of Saint Catherine, the two highest decorations of the Russian Empire. This was King George's second Russian decoration, the first being the Order of Saint Alexander Nevski he received on May 3, 1783.[33]

The first days of his reign were busy with his attempt to assert control over the royal court. Queen Dowager Darejan sought in vain to remain Queen of Kartl-Kakheti by preventing Mariam of that title, but in a show of force, George XII forced Darejan's partisans to pledge their allegiance to his and Queen Mariam's reign.[25] While the royal court remained established in Telavi, Darejan resettled in Tbilisi, the reconstruction of which continued actively under the direct supervision of the king. From there, she would continue to confront her step-son's reign.[25]

Many feared George XII's reign would be a short one. 51 years old, the king was notably overweight and his love of feasts led high nobles to question his capacity to rule a country in crisis.[25] Suffering, like his father, of edema, his movement was limited, a handicap for a nation used to monarchs leading troops themselves on the battlefield.[25]

Crisis of Succession

Following his accession, George XII was forced to sign a decree recognizing his half-brother Iulon as heir to the throne, a decision made by the king to avoid a civil war in a kingdom stuck between the Russian Empire and a hostile Persia.[34] However, he hoped to nullify the decree in favor of his oldest son David, at the time in Russia's military service,[35] a plan quickly discovered by Queen Dowager Darejan and her sons.[36]

The family conflict went deeper than a dynastic dispute. At the core of the disagreement was George XII's foreign policy, a continuation of his father's largely pro-Russian policy.[37] The royal court was divided in two camps – those supporting the king's orientation and those fearing Russian imperialism.[37] The latter were led by Prince Alexander Bagrationi.[38] King George's decision to send Prince George Avalishvili to Saint Petersburg as a special envoy to assist Ambassador Garsevan Chavchavadze to launch negotiations with Emperor Paul I over a renewal of the Treaty of Georgievsk worsened the situation at home, as it became evident Avalishvili was sent to secure the recognition of David as Crown Prince by Russia.[34]

Heraclius II's policy of centralizing the kingdom by granting noble fiefs to the royal family had serious consequences. Pyotr Buktov, a 19th-century Russian historian, explained the situation in Kartl-Kakheti at the ascension of George XII:[39]

The royal princes, put in charge of an important section of the kingdom at the detriment of the aristocracy, did not even think about submitting themselves to the general interest. Each sought to reinforce their party and to become autonomous, or even to spread discord across the kingdom. Such a division of authority in such a small state gave the impression of anarchy.

The royal brothers strengthened themselves in their domains after Avalishvili was sent to Russia, announcing their refusal to recognize George XII as king.[36] In response, the latter confiscated the domains of Queen Dowager Darejan[40] and promulgated a decree restricting the rights of royal princes. The civil war that George XII had sought to avoid began at the time with the capture of the Surami Fortress by Prince Pharnavaz Bagrationi in 1798.[41] Worsening the situation, the kingdom's central army disappeared by being divided amongst the various princes, removing King George's only loyal forces outside of Kakheti.

The king had to hire 1,200 Lezgin soldiers,[40] a decision largely criticized in society as Lezgins had historically been known as enemies of Georgia, often organizing devastating raids since the 16th century. The Lezgins were ordered to restore order in Kartli but they also ravaged villages.[42] The high cost of maintaining these mercenaries led George XII to increase taxes on merchants and on petty nobles and threatened with force any noble house refusing to pay.[42] Across the kingdom, the lack of funds to pay for law enforcement led to an increase in the crime rate.[42]

With the situation collapsing, King George and his brothers opened their doors to foreign intervention.[40] [38] The king sent his embassy to Russia to change the terms of the Treaty of Georgievsk and to allow the Russian Empire to intervene in the internal affairs of Georgia, while granting the Emperor the sole power to recognize the heir to the Georgian throne. On April 18, 1799, the efforts of Ambassador Chavchavadze led to the signing of an imperial edict by Paul I renewing the treaty and recognizing the pro-Russian David, son of King George, as Crown Prince of the "Two Georgias".[43]

Relations with Russia

The renewal of the Treaty of Georgievsk forced Emperor Paul I to review his policy in the Caucasus and start designing a more interventionist approach.[44] Saint Petersburg was forced to reconsider the economic, political and military benefits of imposing itself in the South Caucasus and General Karl Heinrich Knorring, who led at the time the Russian troops in the Caucasus, received new instructions. Unbeknownst to Tbilisi, Paul I signed a secret document along with the treaty renewal ordering General Knorring to secure the annexation of the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti after the death of King George XII.

The Russian Empire sent State Councilor Pyotr Ivanovich Kovalensky as Plenipotentiary Ambassador of Russia to Kartl-Kakheti[43] on November 8, 1799.[45] He was followed on November 26 by Ivan Petrovich Lazarev as head of the Russian forces in Georgia made of two battalions.[43] George XII, seeing this as a diplomatic victory against the anti-Russian noble class, organized a parade to welcome them in the capital and met Kovalensky in the royal palace of Tbilisi.[46] According to 19th-century Georgian poet Ilia Chavchavadze, "a long time would pass before Georgia would be so happy".[46] The people of Tbilisi, still remembering the carnage of the Battle of Krtsanisi, saw the arrival of Orthodox Christian Russians as a guarantee against the Muslim invaders that had devastated the country since the 13th century.[46]

Kovalensky settled in Kartl-Kakheti with a long list of tasks. Most urgently and to satisfy the demands of King George, he served as a guard against the intrigues of Queen Dowager Darejan, who had continued her campaign against the monarch, and to hinder the military resurgence of Persia.[34] To accomplish this, the Russian troops launched the training of a stable army in Kartl-Kakheti, operating by European standards and capable of defending the country and of following the interests of Russia.[34] Kovalensky was also tasked with drawing the different Muslim khans of the Caucasus into the Russian sphere of influence. Followed by a group of merchants, scientists and economic advisers,[47] he also had to evaluate the economic and geographical potential of the region, while implementing economic reforms to improve the trade situation across the South Caucasus.[34]

But Kovalensky's responsibilities rapidly extended far beyond King George's requests. Part of his troops were garrisoned at the Turkish border to avoid all conflict between the Ottoman Empire and the Georgians and to preserve the fragile peace between Russia and the Sublime Porte.[34] He also organized the integration of Armenian communities within the kingdom, each with their own melik (prefect).[34] Finally, the Russian ambassador had to oversee the king's handling of domestic affairs to ensure that his decisions were in agreement with Russian interests.[48]

Kovalensky's powers made him a quasi-governor. Soon, he controlled all correspondence of the king.[43] When George XII fell sick toward the end of 1800, Kovalensky and General Lazarev took charge of the country's management instead of Crown Prince David, who had himself returned from Russia in 1799.[38]

George XII and the Ottomans

Shortly after George XII's arrival to power, he had to face an increasingly tense situation at his southern border. While hostile Persia was at the kingdom's southeast, the southwest shared a border with the Ottoman Empire. Notably, Sabuth, pasha of Childir and brother-in-law of Sultan Selim III, governed the Georgian territories under Ottoman administration with a particular hostility toward Orthodox Georgians.

In order to ensure peace with Istanbul, George XII considered transforming Kartl-Kakheti into an Ottoman protectorate.[42] This act was seen as an attempt by the king to force Russia to reaffirm its military obligations under the Treaty of Georgievsk, obligations it had seldom enforced since the signing of the treaty in 1783.[42] In 1798, George XII sent Prince Aslan Orbeliani to negotiate terms of a protectorate treaty with Pasha Sabuth.

Saint Petersburg responded rapidly to this potential change in Georgia's foreign policy and agreed to the demands of King George's diplomats. George XII cancelled his negotiations with Childir and recalled Aslan Orbeliani. Sabuth, angered by this unexpected and sudden change, launched several raids on border territories, while engaging Caucasus Lezgins to attack Kakheti.[34] The latter ravaged the province from July to September 1798.[49]

In April 1799, French General Napoleon Bonaparte, at the time in the middle of war against the Ottomans in Syria, considered an alliance with King George. He sent an emissary to the royal court, but the latter was intercepted by Sabuth, who had him executed.[50] On April 15, 1799, the news of this potential alliance with France reached Tbilisi, but the king did not seek to renew the opportunity.[50]

Thanks to the official support of Russia toward George XII, Russian diplomat Vasily Tomara, at the time stationed in Istanbul, secured peace between Kartl-Kakheti and Turkey.[51] Sultan Selim III forbade all aggressive action against the Georgian kingdom.[52] But this would not prevent Sabuth to favor the later Avar invasion of Eastern Georgia.[40]

Fear of Persia

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar became Shah of Iran in July 1797 and immediately turned his attention towards the Caucasus, a region historically strategic for Persia as a buffer with the Ottoman and Russian Empires. In June 1798, Persian General Soliman Khaun Qajar[35] led an expedition to the South Caucasus to absorb the various small principalities of the region into Persia's sphere of influence and tried to force George XII's submission,[44] along with sending Crown Prince David as a hostage to Isfahan.[53] In a threatening letter, Soliman Khaun said:[44]

If your good fortune does not allow you and your malicious destiny prevents you from embarking onto this positive path, and if you show yourself irregular in our service, it will become evident: our glorious standard will advance toward your lands and you will face a devastation twice as powerful as under the time of Agha Mohammad Khan. Georgia will once again be destroyed and the Georgian people will face our anger. You shall be wise to accept this advice and to follow our orders.

On 3 July, the Shah sent a standard at the court of George XII to have him pledge allegiance to Persia and, in a clear change of tone, offered wealth and gifts to the king in exchange for a turn in his pro-Russian foreign policy.[42] According to the British diplomatic mission in Saint Petersburg, George XII sent his step-father, Prince George Tsitsishvili as an emissary to Soliman Khaun with a precious watch as a sign of cooperation (instead of a monetary tribute as the state coffers were extremely decrepit at the time).[35] But when the news of a rebellion against Fath-Ali Shah forced Soliman to return to Persia, Tsitsishvili headed back to Tbilisi without presenting the gift.[35]

But Persia's ambitions did not end there. Soon, the Karabakh Khanate, historically under Georgia's sphere of influence, broke its ties with Tbilisi and offered its allegiance to the Persian Shah.[54] Fath-Ali Shah send a new embassy to Tbilisi in 1799 to attempt to force George XII into accepting his demands by pointing out Russia's failures to follow its obligations under the Treaty of Georgievsk.[55] But the arrival of Russian troops in November 1799 allowed Tbilisi to reassert a position of power.

In early 1800, Russian ambassador Pyotr Kovalensky sent Reserve Lieutenant Merabov as special representative to the court of the Shah.[37] Merabov arrived in Tehran with a list of demands, including the return of Persian prisoners of war captured during the Battle of Krtsanisi and the reimbursement of all costs of the 1795 invasion.[56] He also added that Saint Petersburg sought friendly relations with Persia if the latter abandoned all claims to Kartl-Kakheti.[57] Grand Vizier Hajji Ebrahim Shirazi refused Merabov's demands, asked an official embassy from Emperor Paul I, and tried to execute Merabov, who managed to return to Tbilisi through the difficult Rasht-Baku road.[37]

In April 1800,[58] a new Persian embassy arrived in Tbilisi to officially respond to Merabov's demands, threatening George XII with a 60,000-strong invasion.[37] However, the king refused to grant the Persian diplomats a private audience and met them at the Russian Embassy in Tbilisi with Kovalensky.[58] George XII, encouraged by the Russian military presence, categorically refused Fath-Ali Shah's terms, the latter then starting preparations for an invasion.[58]

King within an Empire?

Internal divisions and external threats pushed George XII to seek a new change in his relations with Russia. On September 7, 1799, he sent a letter to his embassy in Saint Petersburg, stating:[59]

Based on the Christian truth, offer my kingdom and my domains to the protection of the Russian Imperial Throne and give Russia complete authority so that the Kingdom of Georgia integrates the Russian Empire with the same status as other provinces of Russia.

Then, ask humbly the Emperor of All Russia to grant me, while accepting the Kingdom of Georgia under his authority, the written promise that the royal dignity will not be removed from my House and will be preserved from generation to generation, as in the time of my ancestors.

Also, submit to His Grace the Emperor a humble petition to offer me a land grant within the borders of the Russian Empire as hereditary possession, that shall serve as guarantee for my final submission.

This demand to annex Kartl-Kakheti into the Russian Empire was based on the ancient Persian system of governance over Georgia, which envisioned a Georgian leader serving as wali (governor) of the Shah but also as mephe (king) to the Georgian people.[45] However, this letter never made it to the Georgian delegation: Kovalensky, jealous of the influence of Georgian ambassador Garsevan Chavchavadze, recalled George XII's diplomats back to Georgia.[60]

In April 1800, King George, once again threatened by Persia, sent another embassy, made of Garsevan Chavchavadze, George Avalishvili and Eleazar Palavandishvili, to Saint Petersburg.[61] They were trusted with a document of the royal court, the Petitionary Articles, listing 16 demands made by the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti to Emperor Paul I.[62] Among these demands were a promise to keep George XII as King with the right to administer his kingdom with the laws of Russia, a guarantee of the right of succession of his descendants, the permanent presence of 6,000 Russian soldiers in the strategic fortresses of the kingdom, the dispatch of Russian merchants to exploit precious metals in Georgia, an assurance against Ottoman raids, and the promise to grant Georgian nobles, clergy members, merchants, and artisans the same rights as their equals in Russia.[61]

While the Georgian embassy reached Saint Petersburg in June, Kovalensky successfully fought to be named Administrator of the Kingdom by George XII, along with the latter's son Ioane Bagrationi.[63] His power increasing, the Georgians managed to convince Russian authorities to dismiss Kovalensky and Emperor Paul I signed a decree to that matter on August 3, 1800, replacing him with Ivan Lazarev, who took over as the head of political and military forces in Kartl-Kakheti.[64]

Negotiations between Georgians and Russians took place from June to November[65] at the College of External Affairs in Saint Petersburg.[66] The Russian side was led by Count Fyodor Vasilyevich Rostopchin[65] and on November 19, 1800, the Russian government agreed to the 16 points of the Petitionary Articles.[67] Prior to the formal integration of the kingdom within the Russian Empire the Georgian emissaries had to return to Tbilisi to seek the final agreement from the Royal Council and the signature of King George XII, before an official act could be issued by Emperor Paul.[67] At the end of November, Avalishvili and Palavandishvili returned towards Georgia to lead a campaign to convince the benefits of the agreement to the public opinion. They were helped by General Knorring, who was still leading the Russian forces in the Caucasus.[68]

Emperor Paul, whose domestic policy became increasingly authoritarian and his international relations increasingly unstable, had other plans for Kartl-Kakheti. Following the British invasion of Malta on September 4, 1800, he imagined granting the Knights of the Order of Malta control over Georgia.[65] He saw the idea of a sovereign king within his autocratic empire as going against the interests of his crown.

Rise in Internal Chaos

Despite his strong foreign policy equipped with a competent diplomatic team, George XII remained largely incapable of controlling his kingdom. This became largely obvious when his younger son Ioane presented him an ambitious plan of reforms on May 10, 1799,[40] a plan that would have radically changed the administrative system of the kingdom and its financial sector, while introducing a public education program. Despite the king's approval, the lack of support by noble and merchant classes prevented its implementation. Queen Mariam herself abused her husband's weakness: she stole the royal insignia to counterfeit the king's signature several times, as the King often loaned the insignia to his younger children as a toy.[55]

George XII was afflicted with a severe paranoia that made him fear assassination.[55] He placed Queen Dowager Darejan under constant surveillance and placed himself under the sole confidence of his three older sons, David, Ioane and Bagrat. The noble class was itself divided between those supporting Darejan and wanting to see Prince Iulon on the throne with a foreign policy moderately favorable towards Russia, and those supporting the pro-Persian clan of Prince Alexander Bagrationi.[37] Some merchants also sought a complete abolition of the monarchy in favor of a republican system.[37]

The arrival of Russian troops in November 1799 only worsened the internal division. Not only Kovalensky was often challenged by General Lazarev, but he also regularly insulted members of the royal family.[69] Moreover, he engaged in a policy of dividing Georgians and Armenians in the kingdom, the latter making up a large part of the bourgeois class of Tbilisi. Two Tbilisi Armenian prefects, Jumshid and Pheridun, received a Russian salary for the spreading of pro-Russian sentiments within the Armenian community of Georgia and were in direct contact with Russian authorities, in violation of the agreement between George XII and Saint Petersburg.[70] Joseph II Argutinsky, the Armenian catholicos consecrated in 1800, encouraged opposition to the king and sponsored his followers' support for Emperor Paul.[42] According to British diplomatic intercepts in India, the Russians had promised the Armenians the creation of an autonomous state within the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti.[71]

Despite her isolation in Tbilisi, Darejan managed to lead a propaganda campaign against George XII throughout the region. She successfully pushed Armenian meliks and Azerbaijani khans against George XII, while seeking her son Iulon's recognition as heir to the throne during secret negotiations with Pasha Subath of Childir and King Solomon II of Imereti, the latter governing Western Georgia.[72] The latter was also opposed to the pro-Russian policy of George XII, complaining to the king of the lack of consultations with the other Georgian states.[73]

In July 1800, princes Iulon, Pharnavaz and Vakhtang gathered 3,000 men under the pretext of preparing against an upcoming Persian invasion, but instead besieged Tbilisi to free Queen Darejan.[74] Ivan Lazarev's Russians destroyed their forces and the rebel troops were dispersed, while Darejan remained imprisoned in the capital.[75]

Persian Invasion Attempt

In April 1800, George XII refused one last time to bow to Persia's demands. In response, Fath-Ali Shah sent an army of 10,000 men[53] under the leadership of his son Abbas Mirza and General Soliman Khaun Qajar[58] to threaten the Georgian borders. The army gathered in Tabriz and announced its intent to walk on Maku, Yerevan and Tbilisi,[58] while Prince Alexander Bagrationi left the kingdom to join them in Azerbaijan in July.[41] Having informed the Persian invading force of the military weaknesses of Kartl-Kakheti, he joined the troops' leadership and was named Khan of Georgia by the Shah,[53] crossing the Aras river and nearing the Georgian borders.[58]

Russian preparations to defend the capital were weak. Kovalensky, with the agreement of George XII, had trenches built around Tbilisi, exposing hundreds of bodies that had been buried after the Battle of Krtsanisi and leading to an epidemy of viral infection across the capital,[76] an epidemy that spread to Kartli. George XII's response was limited to the dispatching of a religious representative across the region.[30]

On July 10, 1800, Emperor Paul I ordered General Knorring to send reinforcements to Georgia.[77] Ten squadrons of cavaliers and nine battalions of armed infantry crossed the North Caucasus's line of defense.[63] In September, General Guliakov and his regiment of Kabardino mousquetaires arrived in Kakheti.[78] These new arrivals discouraged the Persian forces, which had to leave occupied Yerevan to return to Tabriz, while Alexander found refuge in the Karabakh.[63]

Avar Invasion

From his refuge in Yerevan, Prince Alexander joined the Avar lands and managed to convince Omar Khan, the Avar leader since 1774, to side against George XII.[79] Omar Khan, who was formally a vassal of Kartl-Kakheti, hid his invasion plans by requesting a military protection to General Knorring,[80] while rapidly designing a war plan with Darejan's supporters. Alexander and Omar Khan agreed to invade Kakheti, while princes Iulon, Pharnavaz and Vakhtang prepared to occupy the Dariali Gorge, the only opening in the Russia-Georgia natural border, to avoid Russian reinforcements from intervening.[79] The three brothers agreed to divide the kingdom amongst themselves in case of success.[79]

In August 1800, the Avars launched their first attempted invasion in Kakheti's Sagarejo province.[79] However, they were quickly defeated and forced to retrieve by the forces led by princes Ioane and Bagrat, sons of George XII, during a battle in Niakhuri, on the shores of the Alazani river[41] on August 15.[81] But Omar Khan managed to gather new forces and received the military support of Fath-Ali Shah and Pasha Sabuth of Childir.[40] Waiting for a new opportunity to attack, Alexander addressed the Georgian people, swearing on the tomb of Saint Nino that his alliance with Georgia's traditional enemies was only temporary and was meant to restore the legitimate order in the country.[81]

In early November, an army of 12,000 Avars led by Omar Khan and Alexander Bagrationi invaded Kakheti.[81] George XII, increasingly distant from his royal responsibilities, appointed princes Ioane and Bagrat as responsible for the Georgian forces.[79] Ioane became head of the Georgian artillery and was reinforced by the Russian forces of Lazarev and Guliakov.[79] 2,000 Russians, Kakhetians, and mountain militants from Pshavi, Tusheti and Khevsureti, had to face the invaders.[41] On November 7, 1800, the two sides met at the junction of the Iori and Alazani rivers.[41]

During the Battle of Kakabeti,[36] the Georgian-Russian forces came out victorious. Following the loss of 2,000 men,[81] the Avars ran away and Omar Khan was severely injured, dying a few weeks later. Alexander Bagrationi fled to Karabakh with 2,000 partisans.[81] As for their victory, Ioane, Bagrat, Lazarev, and Guliakov were awarded the Order of Saint-John of Jerusalem by Emperor Paul.[82]

Russian Annexation

The Avar invasion forced the Russian authorities to increase their presence in the South Caucasus. On November 15, 1800, while the diplomatic delegation sent by George XII was still negotiating with Saint Petersburg, Emperor Paul I ordered General Knorring to reinforce as much as possible the Russian strongholds already present in Kartl-Kakheti.[65] He ordered the Russian authorities in Tbilisi to prevent the accession to the throne of the dying King George's successor without the direct agreement of Saint Petersburg, a secret order hid from the Georgian diplomats.[83]

Meanwhile, Count Apollo Mussin-Pushkin, an eminent Russian geologist established in the Caucasus since September 1799 to study the economic potential of the kingdom, published a detailed report on Kartl-Kakheti.[53] In it, he mentioned Georgia's geological wealth that Russia could exploit, as well as the benefits of using Tbilisi as a commercial base with Persia and India and Georgia as a military base against the Ottoman Empire, Persia, and Dagestan.[53] Moreover, the report revealed the lack of popularity towards Crown Prince David, the presumed heir to the throne.[84]

General Lazarev presented another report on the socio-political conditions of the kingdom. He detailed the alarming lack of power of George XII and the large opposition against his oldest son. According to Lazarev, the high taxation rate and the general insecurity linked to the internal and external threats had a negative effect on the economy. The lack of funds in the national treasury prevented the royal authorities from paying public salaries, leading to rampant corruption.[84] The population of the kingdom had diminished to a dangerously low level: a census in 1801 counted only 35,000 families across the kingdom and 168,929 residents.[85]

Paul saw these reports as a sign to change his decision towards Georgia in early December and decided to accelerate the process of annexing Kartl-Kakheti without the ratification of George XII.[86] Indeed, the fear of imperial authorities was the death of the sickly monarch before the ratification of the Petitionary Articles, his death probably leading to a new civil war and the capture of Tbilisi by Iulon Bagrationi.[84] The king himself saw the situation with the same eye, writing on December 7, 1800, to Lazarev that "our lands belong to His Imperial Majesty".[87]

On December 17, the Emperor convened the State Imperial Council, led by General Prosecutor Peter Khrisanfovich Obolyaninov.[88] While a majority of Council sided against the direct annexation of the Kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti, Obolianov had the minutes of the meeting changed, declaring that Emperor Paul had already made his decision.[88] These amended minutes were confirmed by imperial prince Alexander Romanov.[88]

On 18 December,[89] while the Georgian emissaries were still en route an while George XII was on his deathbed, Emperor Paul signed the decree annexing the kingdom.[40] He appointed Crown Prince David as administrator of the province and offered Georgian nobles titles of count and barons.[88] This annexation would be formalized only two years later, Paul being murdered a few months later, before the decree could be published in Tbilisi.[90] [91]

Death

In the second half of 1800, George XII fell gravely sick because of his edemas that slowed down his movement. His lack of public appearances made him largely unpopular amongst his subjects.[92] The state affairs were increasingly under the control of Russian official. The king spent his last months restoring the icon of Saint George of Bochorma, a high-mountain village in Tusheti, with artisan Gabriel.[41]

George XII stayed isolated in his palace in Tbilisi. While he trusted only his sons David, Ioane and Bagrat, he set himself apart from David when the latter married on January 9, 1800, Elene Abamelik, the daughter of an Armenian merchant, against the will of his father.[63] Seeking to associate his younger sons to the throne, he named Ioane as Minister of the Armies on 20 November. Seven of his 23 children died before his reign and the king suffered from depression, in addition to his isolation and disease. He would never learn of the signing by Paul I of the decree incorporating Kartl-Kakheti within the Russian Empire, his biggest diplomatic accomplishment. Sick, he sought, in vain, to be healed with Russian medicine and doctor Hirzius.[93]

On December 28, 1800,[38] while his ambassadors were still in the North Caucasus, heading towards Tbilisi with the Russian document,[94] George XII addressed Knorring one last time through a translator, entrusting him his kingdom while asking his priests to ensure the crowning of David.[93] He died the same day in Tbilisi, due to complications from an angina. His crown and scepter were sent to Saint Petersburg.[95] He was the last King of Kartl-Kakheti and the last Georgian sovereign to be buried in the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral of Mtskheta. Crown Prince David immediately took over the kingdom, but remained a titleless governor before the final annexation of the Georgian state in 1802.

Family

Marriages and Children

George XII married in 1766 Princess Ketevan Andronikashvili, daughter of Papuna Andronikashvili, Governor of Kiziqi, when she was 12 years old. She died on June 3, 1782, after the couple had six sons and six daughters:

- David Bagrationi (1767–1819), regent of Kartl-Kakheti;

- Ioane Bagrationi (1768–1839), military and political leader;

- Varvara Bagrationi (1769–1801), wife of Prince Simeon-Zosim Andronikashvili;

- Luarsab Bagrationi (1771–b.1798), died in childhood;

- Sophio Bagrationi (1772–1841), wife of Prince Luarsab Tarkhanishvili;

- Nino Bagrationi (1772–1847), regent of Samegrelo;

- Salome Bagrationi, died in childhood;

- Bagrat Bagrationi (1776–1841), military and political leader in Russia;

- Ripsimi Bagrationi (1776–1847), wife of Prince Dimitri Irubakidze-Choloqashvili;

- Gayana Bagrationi (1780–1820), wife of Prince George Kvenipneveli-Sidamoni;

- Solomon Bagrationi (1780–b.1798), died in childhood;

- Teimuraz Bagrationi (1782–1846), scientist.

After the death of Ketevan, George married on July 13, 1783 Mariam Tsitsishvili, daughter of Prince George Tsitsishvili of Higher Satsitsiano and military commander under Heraclius II. This Mariam would become the Queen of Kartl-Kakheti and would be arrested by Russian authorities for the murder of General Ivan Lazarev who had been sent to deport following the Russian annexation of Georgia. Together, the royal couple gave birth to several children:

- Elizbar Bagrationi (1790–1854), military leader in Russia;

- Michael Bagrationi (1783–1862);

- Jibrail Bagrationi (1788–1862);

- Tamar Bagrationi (1788–1850), later exiled to Moscow;

- Ana Bagrationi (1789–1796), died in childhood;

- Joseph Bagrationi (died before 1798), died in childhood;

- Spiridon Bagrationi (died before 1798), died in childhood;

- Okropir Bagrationi (1795–1857), military leader in Russia;

- Simon Bagrationi (1796 – b. 1798), died in childhood;

- Heraclius Bagrationi (1799–1859);

- Ana Bagrationi (1800–1850), wife of Prince Eustash Abashidze, then David Tsereteli.

Royal Lineage

While the monarchy was abolished by the Russian Empire, a part of the Georgian nobility continued to consider George XII's descendants as heirs to the Georgian throne. Crown Prince David, followed by his brother Ioane, are considered by modern Georgian monarchists as posthumous claimants to the throne of Georgia. It's only in 1865 that George XII's great-grandson Ivan Griogorievich would receive the title of "His Highness Prince Gruzinsky" ("Prince of Georgia") by the Saint Petersburg government.

Nugzar Bagration-Gruzinsky is a claimant to the Georgian throne since 1984. He is the descendant of Bagrat Bagrationi, third son of King George XII, and claims the title of King of Georgia as the oldest descendant of the last crowned king.[96] However, since the 1940s, the cadet Mukhrani branch of the Bagrationi dynasty has also claimed the Georgian throne, arguing that the Gruzinsky branch abandoned all claims by recognizing the Russian rule over Georgia. Georgian monarchists are divided between those supporting Prince Nugzar as the descendent of George XII and those backing the Mukhrani line.

Personality

George XII inherited a kingdom in a dire social and economic situation, the entire region having been devastated by centuries of Muslim invasions. According to several historiographic opinions, he was a poor monarch who failed to address the kingdom's immediate crises. British historian Donald Rayfield has theorized that had Heraclius II's successor been more competent in dealing with internal divisions, Georgia would have been reunited within a single, powerful Caucasian state allied with France, Turkey and Russia.[97]

George was overweight, gluttonous, lazy, and was often of short temper.[25] Suffering from edemas, he had difficulty moving, which contributed to the lack in his popularity.[41] He was rarely interested in domestic affairs, choosing to focus almost entirely on his diplomatic program with Russia. British historian David Marshall Lang wrote in 1957:[25]

He lacked the necessary qualities to lead the country in its situation. The corpulence of his advanced age prevented Giorgi, a famous gourmand, from shining as a military leader. This was a serious handicap in a kingdom accustomed to kings leading their troops into battle.

His incapacity was noted by foreign observers of the time. British ambassador Sir John Malcolm, based in Tehran, spoke of George XII as a monarch "incapable of centering his power".[35] His lack of positive qualities was seemingly obvious before his ascension: as heir to the throne, he often failed to counter his brothers' powers and during the Battle of Krtsanisi, he remained in his stronghold in Sighnaghi instead of coming to his father's aid, failing to convince his troops to leave their vineyards to defend the kingdom against the Persian invaders, even though his own sons David and Ioane led battalions in Tbilisi.[98]

Papuna Orbeliani, a contemporary chronicler, was a lot more generous towards the king, writing:[30]

Since childhood, he proved himself a religious man, very respectful towards the servants of the Church, protecting widows and orphans, gifted with all sorts of virtues, and so impartial in the administration of justice that the great and petty nobles were equal to him.

Bibliography

- Asatiani, Nodar; Bendianashvili, Alexandre (1997). Histoire de la Géorgie. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-7384-6186-7.

- Asatiani, Nodar; Janelidze, Otar (2009). History of Georgia. Tbilisi: Publishing House Petite. ISBN 978-9941-9063-6-7.

- Salia, Kalistrat (1980). Histoire de la nation géorgienne [History of the Georgian nation] (in French). Paris: Nino Salia.

- Lang, David Marshall (1957). The Last Years of Georgian Monarchy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Allen, W.E.D. (1932). A History of the Georgian People. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul.

- Berdzenishvili, Nikoloz (1973). Საქართველოს ისტორიის საკითხები VI [Questions on the History of Georgia, Volume 6] (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

- Asatiani, Nodar (2008). Საქართველოს ისტორია II [History of Georgia, Volume 2] (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press. ISBN 978-9941-13-004-5.

- Bendianashvili, A. (1975). Ქართული საბჭოთა ენცილოპედია, I [Georgian Soviet Encyclopedia, volume 1] (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press.

- Gvosdev, Nikolas K. (2000). Imperial Policies and Perspectives towards Georgia, 1760–1819. London: MacMillan Press LTD. ISBN 0-333-74843-3.

- Berzhe, A.P. (1866). Официальные документы, собранные Кавказской археографической комиссией [Official documents collected by the Caucasus Archeological Commission] (in Russian). Tbilisi.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Takaishvili, Ekvtime (1920). Საქართველოს სიძველენი : Les antiquités géorgiennes (Une collection des chartes historiques géorgiennes), vol. I [Georgian antiquities: A collection of Georgian historical charters, Volume 1] (in French). Tbilisi: Tbilisi University Press.

- Dubrovyn, N.T. (1867). Георгий XII, последний царь грузии [George XII, Last King of Georgia] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tsagareli, A.A. (1902). Chartes et autres documents historiques du xixe siècle sur la Géorgie, vol. II [Charters and other historical documents of the 19th century on Georgia] (in French). Saint Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Braddeley, John F. (1908). The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dolidze, Irma (2014). Museum, History, Artifact : The Gremi Museum. Tbilisi. ISBN 978-9941-0-7176-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tsagareli, A.A. (1901). Novye Materialy dlia zhiznopisaniia i deiatel'nosti S.D. Burnasheva, byvshago v Gruzii s 1783 po 1787 g. Saint Petersburg: Gosudarstvennaia Tipografiia.

- Butkov, P.G. (1869). Материалы для современной истории Кавказа, 1722–1803 [Materials for the Modern History of the Caucasus, 1722–1803] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sokolov, A.E. (1873). Чтения в Императорском обществе русской истории и древностей [Lectures at the Imperial Society of Russian history and antiquities] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires, a History of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-070-2.

- Avalov, Z.D. (1906). Присоединение Грузии к России [Georgia's Annexation by Russia] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brosset, Marie-Félicité (1857). Histoire moderne de la Géorgie [Modern History of Georgia] (in French). Saint Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences.

References

- ^ Salia 1980, p. 438.

- ^ a b c Bendianashvili 1975, p. 532.

- ^ "Batonis Tsikhe feudal complex in Georgia's east reopens with new museum". Agenda.ge. 2018-05-17. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 158.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 239.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d Brosset 1857, p. 246.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 159.

- ^ Tsagareli 1901, p. 20.

- ^ Asatiani 2008, p. 324.

- ^ Asatiani 2008, p. 325.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 241-242.

- ^ Asatiani 2008, p. 331.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 241.

- ^ a b Brosset 1857, p. 247.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 260.

- ^ Gvosdev 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Allen 1932, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Lang 1957, p. 198.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 297.

- ^ Asatiani & Bendianashvili 1997, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Asatiani & Bendianashvili 1997, p. 233.

- ^ Allen 1932, p. 216.

- ^ a b Allen 1932, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lang 1957, p. 226.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 263.

- ^ Takaishvili 1920, p. 223.

- ^ Salia 1980, p. 378.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 264.

- ^ a b c d Brosset 1857, p. 266.

- ^ Dubrovyn 1867, p. 54-55.

- ^ Tsagareli 1902, p. 204-205.

- ^ Brosset 1857, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lang 1957, p. 230.

- ^ a b c d e Lang 1957, p. 228.

- ^ a b c Asatiani & Janelidze 2009, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lang 1957, p. 233.

- ^ a b c d Salia 1980, p. 380.

- ^ Butkov 1869, p. 335-336.

- ^ a b c d e f g Asatiani & Bendianashvili 1997, p. 234.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allen 1932, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berdzenishvili 1973, p. 472.

- ^ a b c d Gvosdev 2000, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Lang 1957, p. 227.

- ^ a b Lang 1957, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Asatiani 2008, p. 358.

- ^ Berdzenishvili 1973, p. 473.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 93-96.

- ^ Gvosdev 2000, p. 77.

- ^ a b Tsagareli 1902, p. 203.

- ^ Butkov 1869, p. 447.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 229.

- ^ a b c d e Gvosdev 2000, p. 80.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 230-231.

- ^ a b c Lang 1957, p. 231.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 234.

- ^ Butkov 1869, p. 451-452.

- ^ a b c d e f Lang 1957, p. 236.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 231-232.

- ^ Sokolov 1873, p. 90.

- ^ a b Gvosdev 2000, p. 82.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 235.

- ^ a b c d Lang 1957, p. 237.

- ^ Tsagareli 1902, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d Lang 1957, p. 239.

- ^ Tsagareli 1902, p. 292-294.

- ^ a b Lang 1957, p. 240.

- ^ Avalov 1906, p. 195.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 99-102.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 234-235.

- ^ Sokolov 1873, p. 110.

- ^ Asatiani 2008, p. 360.

- ^ Rayfield 2012, p. 260.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 108.

- ^ Butkov 1869, p. 453.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 105.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 236-237.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 134-136.

- ^ a b c d e f Lang 1957, p. 238.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 237-238.

- ^ a b c d e Gvosdev 2000, p. 81.

- ^ Butkov 1869, p. 456-459.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 177-178.

- ^ a b c Lang 1957, p. 241.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 193.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 240-241.

- ^ Gvosdev 2000, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Lang 1957, p. 242.

- ^ Braddeley 1908, p. 61.

- ^ Salia 1980, p. 380-381.

- ^ Berdzenishvili 1973, p. 474.

- ^ Berzhe 1866, p. 140.

- ^ a b Rayfield 2012, p. 261.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 243.

- ^ Dolidze 2014, p. 75.

- ^ "The Royal House of Georgia". RoyalHouseofGeorgia.org. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Rayfield 2012, p. 258.

- ^ Lang 1957, p. 216.