Circassian diaspora

| |

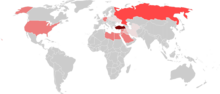

Map of the Circassian diaspora | |

| Total population | |

| c. 5.3 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,000,000–3,000,000[1][2][3] | |

| 751,487[4] | |

| 250,000[5][3] | |

| 80,000–120,000[3][6][7][8][9] | |

| 50,000[citation needed] | |

| 40,000[3][10] | |

| 35,000[11] | |

| 34,000[12] | |

| 25,000[12] | |

| 23,000[citation needed] | |

| 5,000–50,000[13] | |

| 4,000–5,000[14][15][16] | |

| 1,257[17] | |

| 1,001[18] | |

| 1,000[19][20][21] | |

| 500[22] | |

| 400[23] | |

| 116[24] | |

| 54[25] | |

| Languages | |

| Native: West Circassian, East Circassian Diaspora: Turkish, Russian, Arabic, English, German, English, Persian, Hebrew | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Sunni Islam[13]

Minority: Christianity (mostly Eastern Orthodoxy, but also Catholicism),[26] Circassian paganism,[27] irreligion[28] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abazgi peoples (Abkhaz, Abazin), Chechens | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Circassians Адыгэхэр |

|---|

List of notable Circassians Circassian genocide |

| Circassian diaspora |

| Circassian tribes |

|

Surviving Destroyed or barely existing |

| Religion |

|

Religion in Circassia |

| Languages and dialects |

|

| History |

|

Show |

| Culture |

The Circassian diaspora refers to ethnic Circassian people around the world who live outside their homeland Circassia. The majority of the Circassians live in the diaspora, as their ancestors were settled during the resettlement of the Circassian population, especially during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. From 1763 to 1864, the Circassians fought against the Russian Empire in the Russian-Circassian War, finally succumbing to a scorched-earth genocide campaign initiated between 1862 and 1864.[29][30] Afterwards, large numbers of Circassians were exiled and deported to the Ottoman Empire and other nearby regions; others were resettled in Russia far from their home territories.[31][32] Circassians live in more than fifty countries, besides the Republic of Adygea.[33] Total population estimates differ: according to some sources, some two million live in Turkey, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq;[34] other sources have between one and four million in Turkey alone.[35]

Middle East

A large number of Circassians began arriving in the Levant in the 1860s and 1870s through resettlement by the Ottoman Empire, in many cases for political or military reasons. The Ottomans settled them in areas with Muslim minorities and populations that were otherwise of concern to the government; moreover, the dispersion of the Circassians, a warrior people, diminished their possible military threat. An estimated 600 Circassian villages are in Central and Western Anatolia. Likewise, Circassians who moved to Jordan were settled there to counter possible Bedouin attacks. There is a sizeable Circassian population in Syria, which has, to a great extent, preserved its original culture and even its language.[36]

Turkey

Circassians are regarded by historians to play a key role in the history of Turkey. Turkey has the largest Adyghe population in the world, around half of all Circassians live in Turkey, mainly in the provinces of Samsun and Ordu (in Northern Turkey), Kahramanmaraş (in Southern Turkey), Kayseri (in Central Turkey), Bandırma, and Düzce (in Northwest Turkey), along the shores of the Black Sea; the region near the city of Ankara. All citizens of Turkey are considered Turks by the government, but it is estimated that approximately two million ethnic Circassians live in Turkey. The "Circassians" in question do not always speak the languages of their ancestors, and in some cases some of them may describe themselves as "only Turkish". The reason for this loss of identity is mostly due to Turkey's Government assimilation policies[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49] and marriages with non-Circassians. Circassians are regarded by historians to play a key role in the history of Turkey. Some of the exiles and their descendants gained high positions in the Ottoman Empire. Most of the Young Turks were of Circassian origin. Until the end of the First World War, many Circassians actively served in the army. In the period after the First World War, Circassians came to the fore in Anatolia as a group of advanced armament and organizational abilities as a result of the struggle they fought with the Russian troops until they came to the Ottoman lands. However, the situation of the Ottoman Empire after the war caused them to be caught between the different balances of power between Istanbul and Ankara and even become a striking force. For this period, it is not possible to say that Circassians all acted together as in many other groups in Anatolia. The Turkish government removed 14 Circassian villages from Gönen and Manyas regions in December 1922, May and June 1923, without separating women and children, and drove them to different places in Anatolia from Konya to Sivas and Bitlis. This incident had a great impact on the assimilation of Circassians. After 1923, Circassians were restricted by policies such as the prohibition of Circassian language,[37][40][44][45][41][50][47][51][42] changing village names, and surname law[41][42][43] Circassians, who had many problems in maintaining their identity comfortably, were seen as a group that inevitably had to be assimilated.

Iran

The diaspora of Circassians in Iran dates back to the end of the 15th century, when Jonayd of the Ak Koyunlu raided regions of Circassia and carried off prisoners.[52] However, the real large influx of Circassians started by the time of Shah Tahmasp I of the Safavid dynasty, who in four campaigns deported some 30,000 Circassians and Georgians back to Iran. Tahmasp's successors, most notably Shah Abbas, all the way till the time of the Qajar dynasty continued to deport and import hundreds of thousands of Circassians to Iran, while a lesser amount migrated voluntarily. Following the mass expulsion of the native Circassians of the northwest Caucasus in 1864, some of them also migrated to Qajar Iran, where some of these deportees from after 1864 rose to various high ranks such as in the Persian Cossack Brigade, where every member of the army was either Circassian, or any other type of ethnos from the Caucasus.[53] The Circassians in Iran played an important and crucial role in the army, civil administration, and royal harems over the many centuries.[54] Today, they are the third-largest Caucasus derived group in the nation after the Armenians and Georgians.[55]

Egypt

The Circassian diaspora may date back to the end of the fourteenth century: the Circassian population in Egypt claims its descendance from the Mamluks who, during the Mamluk Sultanate, ruled Egypt and Syria.[36] One exception to this is the Abazin community in Egypt which conglomerates in the powerful Abaza Family that claims descent from an Abazin "beloved" female "elder."[56] In Egypt, the Abkhazians took – or were given – the last name "Abaza".[56]

Syria

In 1987, Syria was home to approximately 100,000 Circassians, about half of whom lived in Hauran province,[57] and many of the Circassians used to live in the Golan Heights. During the time of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (1920–1946), Circassians served with the French troops in the "escadron tcherkesse" (Cherkess squadron), earning them enduring distrust from the Syrian Sunni Arabs.[57]

In Quneitra and the Golan Region, there was a numerous Circassian community. Several Circassian leaders wanted in 1938, for the same reasons as their Assyrian, Kurdish and Bedouin counterparts in Al-Jazira province in 1936–1937, a special autonomy status for their region as they feared the prospect of living in an independent Syrian republic under a nationalist Arab government hostile towards the minorities that had collaborated with the colonial power. They also wanted the Golan region to become a national homeland for Circassian refugees from the Caucasus. A Circassian battalion served in the French army and had helped it against the Arab nationalist uprisings. Like in Al-Jazira Province, the French authorities refused to grant any autonomy status to the Golan Circassians.[58]

The Circassians of Syria were actively involved in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Their unit was under the leadership of Jawad Anzor. 200 Circassians were killed in action. They performed well, but the overall failure to stop the founding of Israel led to the special Circassian unit being disbanded.[citation needed] After the Six-Day War of 1967, they withdrew further into Syria, especially to Damascus and Aleppo. They were prevented from returning to the Golan Heights by Israeli occupying forces, but after 1973 some of the returned, now living in two villages, Beer Ajam and Bariqa, where they maintain a traditionally Circassian way of life.[59]

The Circassians in Syria are generally well off. They have very good relations with minorities like Alawites, Druze, Christians and Jews. Many of them work for the government, in civil service, or for the military. The former Syrian interior minister and director of the military police, Bassam Abdel Majeed, was a Circassian.[60] All Circassians learn Arabic and English in school; many speak Adyghe language, but their numbers are dwindling. One kindergarten in Damascus provides Adyghe language education. However, there are no Circassian newspapers, and few Circassian books are printed in Syria.[citation needed] Cultural events play an important role in maintaining the ethnic identity of the Circassians. During holidays and weddings, they perform folk dances and songs in their traditional dress.[57]

Lebanon

In the 1910s, many Circassians immigrated to Northern Lebanon. A population of 56,000 are now settled in Lebanon. Even establishing a group of the Circassians in Lebanon.

Jordan

Between 1878 and 1904, Circassians founded five villages in Jordan: Amman (1878), Wadi al-Sir (1880), Jerash (1884), Na'ur (1901), and al-Rusayfa (1904).[61] Since then, the Circassians have had a major role in the development of Jordan, holding high positions in the Jordanian government, armed forces, air force and police.[62][self-published source] In 1921, Circassians were granted the position of the personal trusted royal guards of King Abdullah the First. Since then, the Circassians have been the royal guard, serving all four of the Jordanian Kings, King Abdullah the First, King Talal the First, King Hussein the First and King Abdullah the Second.[63] In 1932, the Circassian Charity Association was established, making it the second oldest charity group in Jordan. In 1944, Al-Ahli Club was founded, which is a Circassian sports club. In 1950, Al-Jeel Al-Jadeed club opened, aiming to preserve the Circassian Culture. In 2009, the Circassian Culture Academy was founded, aiming to preserve the Circassian language, which comprises the closely related Adyghe and Kabardian languages (considered to be dialects of Circassian by some linguists). In 1994, the Al-Ahli Club established a Circassian folklore dance troupe. The Circassian Culture Academy also has a Circassian Folklore Dance troupe named the Highlanders.

On 21 May 2011, the Circassian community in Jordan organised a protest in front of the Russian embassy in opposition to the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, because the site of the Games was allegedly being built over the site of mass graves of Circassians killed during the Circassian genocide of 1864.[64]

Iraq

Iraq is home to approximately 35,000 Circassians, of mainly West Circassian origin. The Adyghes came to Iraq in two waves: directly from Circassia, and later from the Balkans. They settled in all parts of Iraq – from north to south – but most of all in Iraq's capital Baghdad. It has been reported that there are 30,000 Adyghe families just in Baghdad alone. Many also settled in Kerkuk, Diyala, Fallujah, and other places. Circassians played a major role in different periods throughout Iraq's history, and made great contributions to political and military institutions in the country, to the Iraqi Army in particular. Several Iraqi Prime Ministers have been of Circassian descent.

The Iraqi Circassians mainly speak Mesopotamian Arabic and West Circassian.

Israel

There are five to ten thousand Circassians in Israel, living mostly in Kfar Kama (5,005) and Rehaniya (5,000). These two villages were a part of a larger group of Circassian villages around the Golan Heights. As is the case with Jewish Israelis, and the Druze population living within Israel, Circassian men must complete mandatory military service upon reaching the age of majority. Many Circassians in Israel are employed in the security forces, including in the Israel Border Police, the Israel Defense Forces, the Israel Police and the Israel Prison Service.[65][66]

Libya

Around 35,000 Circassians live in Libya, most of them are in the city of Misurata 200 km east of Tripoli.[67]

Europe

Kosovo

A small minority of Circassians had lived in Kosovo Polje since the late 1880s, as mentioned by Noel Malcolm in his seminal work about that province, but they were repatriated to the Republic of Adygea in southern Russia in the late 1990s.[68]

Poland

A small population of 26 Circassian-speakers lived in Congress Poland in the Russian Partition of Poland, according to the 1897 census.[69]

Romania

There is evidence for the presence of people in the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia with names derived from the Circassians.[70] Furthermore, following the Circassian genocide, around 10,000 Circassians settled in Northern Dobruja, a region now pertaining to Romania. They were later expelled as agreed in the Treaty of San Stefano of 1878, which gave the region to Romania, avoiding any prominent contact between the Romanian state and the Dobrujan Circassians.[71][72]

Current situation

Circassians refer to their diaspora as a genocide; the diaspora is "perhaps the most pressing issue in the region and the most difficult to solve."[citation needed] In 2006, the Russian State Duma refused to accept a petition by the Circassian Congress that would have called the Russian–Circassian War an act of genocide.[34] Hazret Sovmen, President of the Republic of Adygea from 2002 to 2007, referred to the Circassian diaspora as an enduring tragedy and a national catastrophe, claiming the Circassians live in more than fifty countries across the world, most of them far from their "historical homeland".[73] The International Circassian Organization promotes the interests of Circassians, and the advent of the Internet has brought "a sort of virtual Circassian nation" into being.[74]

Statistics by country

| Country | Official figures | % | Current est. Circassian population | Further information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 751,487 (2021 census)[4] | 0.58% | — | — | |

| (1965 census, Circassian speakers)[75] | 0.34% | 1,400,000[76] | Circassians in Turkey | |

| — | — | 100,000[77] | Circassians in Syria | |

| — | — | 180,300[78] | Circassians in Jordan | |

| — | — | 35,000 | Circassians in Iraq | |

| — | — | 4,000[79] | Circassians in Israel | |

| 1,700 (1989 census)[80] | 0.01% | — | — | |

| 1,300 (1989 census)[81] | 0.01% | — | — | |

| 1,100 (2001 census)[82] | 0% | — | — | |

| 800 (1989 census)[83] | 0.01% | — | — | |

| 600−700 (1989 census)[84] | 0.01% | — | — | |

| 300−500 (2018 annually statistics) | ||||

| 500 (2011 census)[85] | 0% | — | — | |

| 300−400 (1995 census)[86] | 0.01% | — | — | |

| 200 (1989 census)[87] | 0% | — | — | |

| 200 (2009 census)[88] | 0% | — | — | |

| 99 (1989 census)[89] | 0% | — | — | |

| 50−100 (2018 annually statistics)[90] | 0% | — | — | |

| 86 (1989 census)[91] | 0% | — | — | |

| 50 (2009 census)[92] | 0% | — | — | |

| 21 (1989 census)[93] | 0% | — | — | |

| 11 (1989 census)[94] | 0% | — | — |

See also

- Circassian nationalism

- Circassians

- Circassians in Iran

- Circassians in Iraq

- Circassians in Israel

- Circassians in Syria

- Circassians in Turkey

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Richmond, Walter (2013). The Circassian Genocide. Rutgers University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0813560694.

- ^ Danver, Steven L. (2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 528. ISBN 978-1317464006.

- ^ a b c d Zhemukhov, Sufian (2008). "Circassian World Responses to the New Challenges" (PDF). PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 54: 2. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "Израйльский сайт ИзРус". Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ "Syrian Circassians returning to Russia's Caucasus region". TRTWorld. TRTWorld and agencies. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

Currently, approximately 80,000 ethnic Circassians live in Syria after their ancestors were forced out of the northern Caucasus by Russians between 1863 and 1867.

- ^ "Syria" Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Library of Congress

- ^ "Независимые английские исследования". Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ "single | The Jamestown Foundation". Jamestown. Jamestown.org. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ^ Lopes, Tiago André Ferreira. "The Offspring of the Arab Spring" (PDF). Strategic Outlook. Observatory for Human Security (OSH). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "Via Jamestown Foundation". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Adyghe by country". Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Circassians in Iran". Caucasus Times. 9 February 2018.

- ^ Besleney, Zeynel Abidin (2014). The Circassian Diaspora in Turkey: A Political History. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 978-1317910046.

- ^ Torstrick, Rebecca L. (2004). Culture and Customs of Israel. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 978-0313320910.

- ^ Louër, Laurence (2007). To be an Arab in Israel. Columbia University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0231140683.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "Circassian Princes in Poland: The Five Princes, by Marcin Kruszynski". www.circassianworld.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Polish-Circassian Relation in 19th Century, by Radosław Żurawski vel Grajewski". www.circassianworld.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Polonya'daki Çerkes Prensler: Beş Prens". cherkessia.net. 26 December 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Zhemukhov, Sufian, Circassian World: Responses to the New Challenges, archived from the original on 12 October 2009

- ^ Hildebrandt, Amber (14 August 2012). "Russia's Sochi Olympics awakens Circassian anger". CBC News.

- ^ "Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь" (PDF) (in Belarusian). Statistics of Belarus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2013.

- ^ "Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ James Stuart Olson, ed. (1994). An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-313-27497-8. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ 2012 Survey Maps Archived 20 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. "Ogonek". No 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Svetlana Lyagusheva (2005). "Islam and the Traditional Moral Code of Adyghes". Iran and the Caucasus. 9 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1163/1573384054068123. JSTOR 4030903.

in February 1996... Respondents in the 20–35 age grouop... 26 percent considered themselves atheists...

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Allen and Muratoff 107–108.

- ^ Shawkat.

- ^ Brooks [page needed].

- ^ Shenfield. [page needed]

- ^ Richmond 2.

- ^ a b Richmond 172-73.

- ^ Stokes 152.

- ^ a b Hille 50.

- ^ a b Ayhan Aktar, "Cumhuriyet’in Đlk Yıllarında Uygulanan ‘Türklestirme’ Politikaları," in Varlık Vergisi ve 'Türklestirme' Politikaları,2nd ed. (Istanbul: Iletisim, 2000), 101.

- ^ Davison, Roderic H. (2013). Essays in Ottoman and Turkish History, 1774-1923: The Impact of the West. University of Texas Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0292758940. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı; Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528.

- ^ a b Soner, Çağaptay (2006). Otuzlarda Türk Milliyetçiliğinde Irk, Dil ve Etnisite (in Turkish). İstanbul. pp. 25–26.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. 18 (4): 400. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2005.00262.x. S2CID 59138386. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Suny, edited by Ronald Grigor; Goçek,, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (23 February 2011). A question of genocide : Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539374-3.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b İnce, Başak (26 April 2012). Citizenship and identity in Turkey : from Atatürk's republic to the present day. Londra: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-026-1.

- ^ a b Kieser, ed. by Hans-Lukas (2006). Turkey beyond nationalism: towards post-nationalist identities ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Londra [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 45. ISBN 9781845111410. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Ertürk, Nergis (19 October 2011). Grammatology and literary modernity in Turkey. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199746682.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı & Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ a b editor, Sibel Bozdoǧan, Gülru Necipoğlu, editors; Julia Bailey, managing (2007). Muqarnas : an annual on the visual culture of the Islamic world. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004163201.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aslan, Senem (17 May 2007). ""Citizen, Speak Turkish!": A Nation in the Making". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 13 (2): 245–272. doi:10.1080/13537110701293500. S2CID 144367148.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor; Göçek, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M. (2 February 2011). A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978104-1.

- ^ Sofos, Umut Özkırımlı & Spyros A. (2008). Tormented by history: nationalism in Greece and Turkey. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780231700528.

- ^ Aslan, Senem (April 2007). ""Citizen, Speak Turkish!": A Nation in the Making". Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. Vol. 13, no. 2. Routledge, part of the Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 245–272.

- ^ Eskandar Beg, I, pp. 17-18

- ^ "The Iranian Armed Forces in Politics, Revolution and War: Part One". Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ P Bushkovitch, Princes Cherkasskii or Circassian Murzas, pp.12-13

- ^ Facts On File, Incorporated (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Facts On File library of world history. Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4381-2676-0.

- ^ a b Afaf Lutfi Sayyid-Marsot, Egypt in the reign of Muhammad Ali Pasha, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b c "Syria."

- ^ M. Proux, "Les Tcherkesses", La France méditerranéenne et africaine, IV, 1938

- ^ Stokes 154–55.

- ^ "Al-Ahram Weekly | Region | Strengthening the line". Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Hamed-Troyansky, Vladimir (2017). "Circassian Refugees and the Making of Amman, 1878–1914". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 49 (4): 605–623. doi:10.1017/S0020743817000617. S2CID 165801425.

- ^ Natho, Kadir (2009). Circassian History. Xlibris Corporation. p. 485. ISBN 978-1-4415-2389-1.

- ^ Wallace, Charles (17 May 1987). "Circassians' Special Niche in Jordan : 'Cossacks' Seem out of Place in Arab Palace". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Stephen Shenfield, "CircassianWorld," 2006, "THE CIRCASSIANS - A FORGOTTEN GENOCIDE?" http://www.circassianworld.com/pdf/A_Forgotten_Genocide.pdf

- ^ Slackman, Michael (10 August 2006). "Seeking Roots Beyond the Nation They Helped Establish". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ "Circassians in bid to save language: Diaspora in Jordan attempt to revive their ancient language before it dies out." Al Jazeera English, 14 May 2010 http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/2010/05/201051411954269319.html

- ^ Zhemukhov, Sufian (5 September 2011). "Влияние арабских революций на черкесский мир". Echo of Moscow (in Russian).

- ^ "Circassians flee Kosovo conflict."

- ^ "Привислинские губернии". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Cosniceanu, Maria (2013). "Nume de familie provenite de la etnonime (I)". Philologia (in Romanian). 266 (1–2): 75–81.

- ^ Tița, Diana (16 September 2018). "Povestea dramatică a cerchezilor din Dobrogea". Historia (in Romanian).

- ^ Parlog, Nicu (2 December 2012). "Cerchezii: misterioasa națiune pe ale cărei pământuri se desfășoară Olimpiada de la Soci". Descoperă.ro (in Romanian).

- ^ Richmond 1-2.

- ^ Richmond xii.

- ^ Heinz Kloss & Grant McConnel, Linguistic composition of the nations of the world, vol,5, Europe and USSR, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1984, ISBN 2-7637-7044-4

- ^ "Turkey - People Groups. Adyghe and Kabardian". Joshua Project.

- ^ Lopes, Tiago Ferreira. "The Offspring of the Arab Spring" (PDF). Strategic Outlook. Observatory for Human Security (OSH). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "Jordan - People Groups. Adyghe and Kabardian". Joshua Project.

- ^ "Circassians Are Israel's Other Muslims". FORWARD. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "The distribution of the population by nationality and mother tongue". Ukrainian Census (2001). Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "ДОКЛАД за ПРЕБРОЯВАНЕТО НАНАСЕЛЕНИЕТО В БЪЛГАРИЯ 2011г" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2014 – via Scribd.

- ^ Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году.. asgabat.net (in Russian). Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (PDF). Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Demoscope. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības (Datums=01.01.2014)" (PDF) (in Latvian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Таджикская ССР". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "3.1. Численность постоянного населения по национальностям" (PDF) (in Russian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Эстонская ССР". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ "Литовская ССР". Demoscope Weekly. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- Bibliography

- Allen, W.E.D. and Muratoff, Paul. Caucasian Battlefields: History of the Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border 1828-1921 Cambridge University Press, 1953.

- Brooks, Willis (1995). "Russia's conquest and pacification of the Caucasus: Relocation becomes a pogrom on the post-Crimean period". Nationalities Papers. 23 (4): 675–86. doi:10.1080/00905999508408410. S2CID 128875427.

- "Circassians flee Kosovo conflict". BBC News. 2 August 1998. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Hille, Charlotte (2010). State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus. Brill. p. 50. ISBN 978-90-04-17901-1.

- Mufti, Shaukat (1972). Heroes and Emperors in Circassian History. Lawrence Verry Incorporated.

- Richmond, Walter (2008). The Northwest Caucasus: past, present, future. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-77615-8.

- Shenfield, Stephen D. (1999) "The Circassians - A Forgotten Genocide?" in Levene, Mark and Roberts, Penny (eds.) (1999) The Massacre in History Berghahn Books, New York, ISBN 1-57181-934-7.

- Stokes, Jamie (2009). "Circassians". Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Volume 1. Infobase Publishing. pp. 150–59. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- "Syria". Library of Congress. Retrieved 23 November 2010.