Drosophilidae

| Drosophilidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lordiphosa andalusiaca | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Superfamily: | Ephydroidea |

| Family: | Drosophilidae Róndani, 1856 |

| Subfamily | |

The Drosophilidae are a diverse, cosmopolitan family of flies, which includes fruit flies. Another unrelated family of flies, Tephritidae, also includes species known as "small fruit flies". The best known species of the Drosophilidae is Drosophila melanogaster, within the genus Drosophila, and this species is used extensively for studies concerning genetics, development, physiology, ecology and behaviour. This fruit fly is mostly composed of post-mitotic cells, has a very short lifespan, and shows gradual aging. As in other species, temperature influences the life history of the animal. Several genes have been identified that can be manipulated to extend the lifespan of these insects. Additionally, Drosophila subobscura, also within the genus Drosophila, has been reputed as a model organism for evolutionary-biological studies.[1]

Economic significance

Generally, drosophilids are considered to be nuisance flies rather than pests, since most species breed in rotting material. Zaprionus indianus Gupta is unusual among Drosophilidae species in being a serious, primary pest of at least one commercial fruit, figs in Brazil.[2] Another species, Drosophila suzukii, infests thin-skinned fruit such as raspberries and cherries and can be a serious agricultural pest.[3] Drosophila repleta larvae inhabit drains and spread bacteria. Fruit flies in general are considered as a common vector in propagating acetic acid bacteria[4] in nature. This often ruins the alcohol fermentation process and can ruin beer or wine by turning it into vinegar.

Identification

The diagnostic characteristics for Drosophilidae include the presence of an incomplete subcostal vein, two breaks in the costal vein, a small anal cell in the wing, convergent postocellar bristles; and usually three frontal bristles on each side of the head, one directed forward and the other two directed rearward. More extensive identification characteristics can be found in "Drosophila: A Guide to Species Identification and Use" by Therese A. Markow and Patrick O'Grady, (Academic Press, 2005) ISBN 0-12-473052-3 or "Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook" by M. Ashburner, K. Golic, S. Hawley, (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2005).

Anti-parasitic behavior

Of their many defenses against parasites, when Drosophila melanogaster flies see female larval endoparasitoid wasps, they switch to laying their eggs in alcohol-laden food sources such as rotting fruit. Doing so protects the flies from becoming host to the larvae, as the wasps have a low alcohol tolerance. This oviposition behavior change only occurs upon seeing the female wasp larva and does not take place in the presence of the male wasp larva.[5]

Mutualism

There is evidence to support that pathogens living within certain flies are beneficial to the behavior and survival of the host. One such example of this is in the fly Scaptomyza flava, which carries the pathogen Pseudomonas syringae in exchange for the pathogen damaging the anti-herbivore defenses of main food source for the fly, plants in the family Brassicaceae.[6]

Phylogeny

The family contains more than 4,000 species classified under 75 genera. Recently, a comprehensive phylogenetic classification of the genera based on both molecular and morphological characters has been published.[7]

- Subfamily Drosophilinae Rondani, 1856:

- Tribe Colocasiomyini Okada, 1989:

- Genus Baeodrosophila Wheeler & Takada, 1964

- Genus Balara Bock, 1982

- Genus Chymomyza Czerny, 1903

- Genus Colocasiomyia de Meijere, 1914

- Genus Lissocephala Malloch, 1929

- Genus Neotanygastrella Duda, 1925

- Genus Phorticella Duda, 1924

- Genus Scaptodrosophila Duda, 1923

- Genus Protochymomyza Grimaldi, 1987

- Tribe Drosophilini Okada, 1989:

- Genus Arengomyia Yafuso & Toda, 2008

- Genus Bialba Bock, 1989

- Genus Calodrosophila Wheeler & Takada, 1964

- Genus Celidosoma Hardy, 1965

- Genus Collessia Bock, 1982

- Genus Dettopsomyia Lamb, 1914

- Genus Dichaetophora Duda, 1940

- Genus Dicladochaeta Malloch, 1932

- Genus Drosophila Fallén, 1823

- Genus Hirtodrosophila Duda, 1923

- Genus Hypselothyrea Okada, 1956

- Genus Idiomyia Grimshaw, 1901 (Hawaiian Drosophila)

- Genus Jeannelopsis Séguy, 1938

- Genus Laccodrosophila Duda, 1927

- Genus Liodrosophila Duda, 1922

- Genus Lordiphosa Basden, 1961

- Genus Microdrosophila Malloch, 1921

- Genus Miomyia Grimaldi, 1987

- Genus Mulgravea Bock, 1982

- Genus Mycodrosophila Oldenberg, 1914

- Genus Palmomyia Grimaldi, 2003

- Genus Paraliodrosophila Duda, 1925

- Genus Paramycodrosophila Duda, 1924

- Genus Poliocephala Bock, 1989

- Genus Samoaia Malloch, 1934

- Genus Scaptomyza Hardy, 1849

- Genus Sphaerogastrella Duda, 1922

- Genus Styloptera Duda, 1924

- Genus Tambourella Wheeler, 1957

- Genus Zaprionus Coquillett, 1902

- Genus Zaropunis Tsacas, 1990

- Genus Zapriothrica Wheeler, 1956

- Genus Zygothrica Wiedemann, 1830

- Incertae sedis:

- Genus Marquesia Malloch, 1932

- Tribe Colocasiomyini Okada, 1989:

- Subfamily Steganinae Hendel, 1917:

- Tribe Gitonini Grimaldi, 1990:

- Genus Allopygaea Tsacas, 2000

- Genus Acletoxenus Frauenfeld, 1868

- Genus Amiota Loew, 1862

- Genus Apenthecia Tsacas, 1983

- Genus Apsiphortica Okada, 1971

- Genus Cacoxenus Loew, 1858

- Genus Crincosia Bock, 1982

- Genus Electrophortica Hennig, 1965

- Genus Erima Kertész, 1899

- Genus Gitona Meigen, 1830

- Genus Hyalistata Wheeler, 1960

- Genus Luzonimyia Malloch, 1926

- Genus Mayagueza Wheeler, 1960

- Genus Paracacoxenus Hardy & Wheeler, 1960

- Genus Paraleucophenga Hendel, 1914

- Genus Paraphortica Duda, 1934

- Genus Phortica Schiner, 1862

- Genus Pseudiastata Coquillett, 1901

- Genus Pseudocacoxenus Duda, 1925

- Genus Rhinoleucophenga Hendel, 1917

- Genus Soederbomia Hendel, 1938

- Genus Trachyleucophenga Hendel, 1917

- Tribe Steganini Okada, 1989:

- Genus Eostegana Hendel, 1913

- Genus Leucophenga Mik, 1866

- Genus Pararhinoleucophenga Duda, 1924

- Genus Parastegana Okada, 1971

- Genus Pseudostegana Okada, 1978

- Genus Stegana Meigen, 1830

- Incertae sedis:

- Genus Neorhinoleucophenga Duda, 1924

- Genus Pyrgometopa Kertész, 1901

- Tribe Gitonini Grimaldi, 1990:

-

Close-up of fruit fly proboscis

-

Front view

-

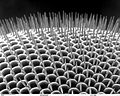

Drosophilidae compound eye

References

- ^ Krimbas, C.B. & Loukas,M.(1980) Inversion Polymorphism of Drosophila subobscura Evol.Biol.12,163-234.

- ^ "Pest Alerts - Zaprionus indianus Gupta, DPI". Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2013-10-05.

- ^ Drosophila suzukii Center of Invasive Species Research

- ^ Vinegars of the World. Chapter 5. ISBN 978-88-470-0865-6

- ^ Kacsoh BZ; Lynch ZR; Mortimer NT; Schlenke TA (Feb 2013). "fruit flies medicate offspring after seeing parasites". Science. 339 (6122): 947–950. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..947K. doi:10.1126/science.1229625. PMC 3760715. PMID 23430653.

- ^ Groen, Simon C.; Humphrey, Parris T.; Chevasco, Daniela; Ausubel, Frederick M.; Pierce, Naomi E.; Whiteman, Noah K. (January 2016). "Pseudomonas syringae enhances herbivory by suppressing the reactive oxygen burst in Arabidopsis". Journal of Insect Physiology. 84: 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.07.011. ISSN 1879-1611. PMC 4721946. PMID 26205072.

- ^ Yassin, Amir (2013). "Phylogenetic classification of the Drosophilidae Rondani (Diptera): The role of morphology in the postgenomic era". Systematic Entomology. 38 (2): 349–364. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2012.00665.x.