Novelty Glass Company

| |

| Company type | Corporation |

|---|---|

| Industry | Glass manufacturing |

| Predecessor | Buttler Art Glass Co. |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Defunct | 1893 |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Successor | Factory T of United States Glass Company |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Rawson Crocker, Henry Crimmel |

| Products | stemware, bar goods, novelties |

Number of employees | 100(1892) |

Novelty Glass Company of Fostoria was one of over 70 glass manufacturing companies that operated in northwest Ohio during the region's brief Gas Boom in the late 19th century. The company made drinking glasses, bar goods, and novelties. Organization of the firm began late in 1890, with banker Rawson Crocker as president and veteran glass man Henry Crimmel as plant manager. Production started in February 1891. The plant was built on the site of the former Buttler Art Glass Company, which had been destroyed by fire in 1889.

During the early 1890s, many manufacturers were producing novelties that honored the 400th anniversary of the voyages of Christopher Columbus. Novelty Glass Company's contribution included commemorative punch bowl sets and salt shakers. Some of this glassware displayed Columbus with a beard—which was rarely done. This commemorative work has subsequently become valuable to collectors.

Like many companies during northwest Ohio’s brief Gas Boom, the Novelty Glass Company was short-lived. The plant was shut down in January 1892, with a restart planned for April. The April restart did not happen, and plant manager Henry Crimmel left the firm for the Sneath Glass Company in Tiffin, Ohio. In October of the same year, the Novelty plant was leased to the United States Glass Company, who also purchased the company's inventory of molds and related equipment. Production began again, and the Novelty works became known as Factory T in the United States Glass Company conglomerate. Approximately 100 people were employed making drinking glasses and stemware. The restart did not last long, however. The plant was destroyed by fire in April 1893.

History

Northwest Ohio gas boom

In early 1886, a major discovery of natural gas occurred in northwest Ohio near the small village of Findlay.[1] Although small natural gas wells had been drilled in the area earlier, this well (known as the Karg well) was much more productive than those drilled before. Soon, many more wells were drilled, and the area experienced an economic boom as gas workers, businesses, and factories were drawn to the area.[1] In 1888, Findlay community leaders, assuming the supply of natural gas was unlimited, started a campaign to lure more manufacturing plants to the area. Incentives to relocate to Findlay included free natural gas, free land, and cash.[2] These incentives were especially attractive to glass manufacturers, since the glass manufacturing process was energy-intensive, and natural gas was a source of energy that was superior to coal in the glassmaking process.[3]

Ohio already had a glass industry located principally in the eastern portion of the state, especially in Belmont County. The Belmont County community of Bellaire, located across the Ohio River from Wheeling, West Virginia, was known as "Glass City" from 1870 to 1885.[4] The gas boom in northwestern Ohio enabled the state to improve its national ranking as a manufacturer of glass from 4th in 1880 to 2nd in 1890.[5] Over 70 glass companies operated in northwest Ohio between 1880 and 1920.[6] However, northwest Ohio’s gas boom lasted only five years. By 1890, the region was experiencing difficulty with its gas supply, and many manufacturers were already shutting down or considering relocating.[6]

Fostoria

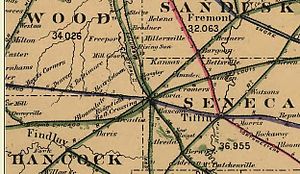

Fostoria, Ohio, is located 12 miles east of Findlay, and straddles three Ohio counties: Hancock, Seneca, and Wood.[3] The high-output gas well that changed the area’s economy was drilled on Karg property in Hancock County.[7] After the Karg well discovery, geologists determined that natural gas would not be found in the immediate area around Fostoria.[3] However, Fostoria government leaders constructed a pipeline from a nearby well in Wood County, and this enabled Fostoria to participate in the rush to lure manufacturers to the area.[8] Fostoria also had a transportation advantage: five railroad lines ran through the city at that time.[Note 1]

The first three glass factories established in Fostoria were the Mambourg Glass Company, the Fostoria Glass Company and the Buttler Art Glass Company. Eventually, Fostoria had 13 different glass companies at various times between 1887 and 1920.[Note 2]

Organization

Events at two other Fostoria glass factories led to the creation of Novelty Glass Company. First, the Buttler Art Glass plant, located at the corner of Buckley and Sandusky streets in Fostoria, burnt to the ground in November 1889. Owners of the plant decided to rebuild elsewhere, since the site had few fire hydrants and inferior water pressure.[10] The second event involved the Fostoria Glass Company. Owners of this company began planning to move to Moundsville, West Virginia in 1890. Plant manager (and shareholder) Henry Crimmel was involved in a lawsuit that sought to prevent the move. Although a temporary restraining order was granted, the company moved to Moundsville during December 1891.[11]

During 1890, planning began to organize a new glass works that would be built on the site of the former Buttler Art Glass Company. The new glass works was to be called Novelty Glass Company. The seven incorporators of the company were Rawson Crocker, Andrew Emerine, Charles Olmsted, C. German, George Flechtner, A. Clyde Crimmel, and Henry Crimmel.[12] The company’s directors were Crocker, Olmsted, Emerine, Henry Crimmel, and Charles Foster. The Crimmels provided the glass making expertise, and worked (and were shareholders) at the Fostoria Glass Company. Crocker, Olmsted (Foster’s brother-in-law), and Emerine were prominent Fostoria capitalists. Charles Foster was a former governor of Ohio, and son of Fostoria’s namesake. Rawson Crocker was Foster’s cousin, an officer of a local bank, and president of the Crocker Window Glass Company.[13]

Rawson Crocker was named president of the new company, and Andrew Emerine was treasurer. A. C. Crimmel was company secretary, while Henry Crimmel was plant manager.[Note 3] The company was expected to employ about 150 people, and produce blown glassware.[13] Pressed glassware was also part of the planning. In late 1890, Henry Crimmel made a trip to Bellaire, Ohio, where he purchased some molds from the Belmont Glass Company. The Belmont works had shut down earlier in the year, and Crimmel had been a manager at that plant before leaving for the Fostoria Glass Company.[12]

Production

Plans for the new glass works included a medium-sized furnace and three lehrs for cooling the glass. Production began in early February 1891.[12] Advertising by the new glass works called the company “The Fostoria Novelty Glass Company”, and news articles called the new company both “Fostoria Novelty Glass Company” and “Novelty Glass Company. (An unrelated company called Fostoria Glass Novelty Company started about 25 years later.)[16] The company’s products were described in advertisements as “fine lead blown tumblers, bar goods, stemware, and novelties”.

At the time the Novelty Glass Company began production, the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America (in 1492) was only a year away.[Note 4] The World’s Fair, also called the Columbian Exposition, was being held in Chicago to celebrate this occasion, and many manufacturers were producing items to commemorate both Columbus and the World’s Fair.[17] The Novelty Glass Company produced punch bowl sets and salt shakers honoring Columbus and Queen Isabella, who financed the expedition. Some of the Columbus novelties featured the explorer with a beard—which was unusual at that time.[18] Because of the short life of the Novelty Glass Company, and the uniqueness of its Columbus glass novelties, those products are valuable to collectors.[Note 5] Typical of many valuable collectibles, potential buyers should be alert for forgeries.[Note 6]

Novelty Glass continued production until the summer, when glass factories traditionally closed for two months. After the end-of-summer startup, the factory closed again in January 1892, with a restart planned for April.[21]

Decline

This U.S. economy suffered through multiple recessions during the 1890s, making life difficult for manufacturing firms.[22] After a January 1892 shutdown, the Novelty Glass Company did not receive enough new orders to justify reopening. During May 1892, plant manager Henry Crimmel left town to become the manager of Sneath Glass Company in Tiffin, Ohio.[23] In October, shareholders sold Novelty’s equipment to the United States Glass Company. The conglomerate also leased Novelty’s glassmaking plant. The plant began operating as Factory T of the United States Glass Company, and had 100 employees. On April 1, 1893, like the Butler Art Glass plant a few years earlier, the glass works was destroyed by fire.[24] Management at the U.S. Glass Company decided not to continue operations. Shareholders of the Novelty Glass Company still owned the land and the ruins of the plant, and voted to liquidate the property in 1896.[25]

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^ Fostoria’s five railroads, sometimes listed in advertisements by Fostoria Glass Companies in 1891, were: the Lake Erie and Western Railroad; the Columbus, Hocking Valley and Toledo Railway; the Toledo and Ohio Central Railway; the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad (a.k.a. the Nickel Plate Railroad); and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

- ^ The count of Fostoria glass companies varies depending on how restarts and reorganizations are counted. The Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association lists 13 companies.[9] Murray writes about 13 companies in his Fostoria, Ohio Glass II, while Paquette lists 15 companies plus 4 post-boom companies in Chapter V of his Blowpipes book.

- ^ At that time, Alva Clyde Crimmel was sometimes identified by the press as Henry Crimmel’s brother.[13] However, he was identified as Henry Crimmel’s son in the elder Crimmel’s 1917 obituaries.[14][15]

- ^ Leif Ericson is known to have visited the shores of North America hundreds of years before Columbus. While there is some debate as to who should receive credit for discovering America, the voyages of Christopher Columbus are certainly significant events.

- ^ In 1998, one set of salt shakers manufactured by Novelty Glass Company was estimated to be worth $1,500.[19]

- ^ The Lechners devote a section of their book to “Reproductions, Look Alikes, Reissues, and Fakes” on pages 269-296.[20]

- References

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, pp. 24–25

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 26

- ^ a b c Murray 1992, p. 12

- ^ McKelvey 1903, p. 170

- ^ United States Census Office 1895, p. 311

- ^ a b Paquette 2002, p. 28

- ^ Murray 1992, p. 11

- ^ Murray 1992, p. 13

- ^ "Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association". Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ Murray 1992, pp. 101–102

- ^ Murray 1992, pp. 57–58

- ^ a b c Murray 1992, p. 33

- ^ a b c Paquette 2002, pp. 205–206

- ^ "H. Crimmel Drops Dead on Street". Hartford City News. October 10, 1917. p. 1.

- ^ National Glass Budget 1917, p. 1

- ^ Reed 2005, p. 1

- ^ Reed 2005, p. 2

- ^ Murray 1992, pp. 33–34

- ^ Lechner & Lechner 1998, p. 145

- ^ Lechner & Lechner 1998, pp. 269–296

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 206

- ^ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ Murray 1992, p. 34

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 217

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 218

- Cited works

- Lechner, Mildred; Lechner, Ralph (1998). The World of Salt Shakers: Antique & Art Glass Value Guide Volume III. Paducah, Kentucky: Collector Books. p. 312. ISBN 9781574320657. OCLC 39502285.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKelvey, Alexander T. (1903). Centennial History of Belmont county, Ohio and Representative Citizens. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company. pp. 833. OCLC 318390043.

Centennial history of belmont county.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Murray, Melvin L. (1992). Fostoria, Ohio Glass II. Fostoria, OH: M. L. Murray. p. 184. OCLC 27036061.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - National Glass Budget (1917). "Henry Crimmel Dead". Nation Glass Budget Weekly Review of the American Glass Industry. 33 (23). Pittsburgh: National Glass Budget. OCLC 473116336.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. p. 559. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reed, Sarah M. (2005). "Novelty Glass Company (1890-1893) and Fostoria Glass Novelty Co. (c. 1915-1917)". Victoria Views. 12 (4 (December)). Fostoria, OH: The Fostoria, Ohio Glass Association.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - United States Census Office (1895). Report on manufacturing industries in the United States at the eleventh census: 1890. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 10470409.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Glassmaking companies of the United States

- Defunct glassmaking companies

- Defunct manufacturing companies of the United States

- Fostoria, Ohio

- Manufacturing companies based in Ohio

- Defunct companies based in Indiana

- Manufacturing companies established in 1890

- Manufacturing companies disestablished in 1893

- 1890 establishments in Ohio

- 1893 disestablishments in Ohio

- Glass trademarks and brands