Gotham City

Gotham City (/ˈɡɒθəm/ GOTH-əm), or simply Gotham, is a fictional city appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics, best known as the home of Batman. The city was first identified as Batman's place of residence in Batman #4 (December 1940) and has since been the primary setting for stories featuring the character.

Gotham City is traditionally depicted as being located in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Over the years, Gotham's look and atmosphere has been influenced by cities such as New York City[7][8] and Chicago.[9][10]

Locations used as inspiration or filming locations for Gotham City in the live-action Batman films and television series have included New York City, New Jersey, Chicago, Vancouver, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, London, Toronto, and Hong Kong.

Origin of name

Writer Bill Finger, on the naming of the city and the reason for changing Batman's locale from New York City to a fictional city, said, "Originally I was going to call Gotham City 'Civic City.' Then I tried 'Capital City,' then 'Coast City.' Then I flipped through the New York City phone book and spotted the name 'Gotham Jewelers' and said, 'That's it,' Gotham City. We didn't call it New York because we wanted anybody in any city to identify with it."[11]

"Gotham" has been a nickname for New York City that first became popular in the nineteenth century; Washington Irving had first attached it to New York in the November 11, 1807 edition of his Salmagundi,[12] a periodical which lampooned New York culture and politics. Irving took the name from the village of Gotham, Nottinghamshire, England: a place inhabited, according to folklore, by fools.[13][14]

Geography

Location in New Jersey

Gotham City, like other cities in the DC Universe, has varied in its portrayals over the decades, but the city's location is traditionally depicted as being in the state of New Jersey. In Amazing World of DC Comics #14 (March 1977), publisher Mark Gruenwald discusses the history of the Justice League and indicates that Gotham City is located in New Jersey.[1]

In the World's Greatest Super Heroes (August 1978) comic strip, a map is shown placing Gotham City in New Jersey and Metropolis in Delaware.[15] World's Finest Comics #259 (November 1979) also confirms that Gotham is in New Jersey.[16] New Adventures of Superboy #22 (October 1981) and the 1990 Atlas of the DC Universe both show maps of Gotham City in New Jersey and Metropolis in the state of Delaware.[17][6]

Detective Comics #503 (June 1983) includes several references suggesting Gotham City is in New Jersey. A location on the Jersey Shore is described as "twenty miles north of Gotham". Within the same issue, Robin and Batgirl drive from a "secret New Jersey airfield" to Gotham City and then drive on the "Hudson County Highway";[citation needed] Hudson County is the name of an actual county in New Jersey.

Batman: Shadow of the Bat, Annual #1 (June 1993) further establishes that Gotham City is in New Jersey. Sal E. Jordan's driver's license in the comic shows his address as "72 Faxcol Dr Gotham City, NJ 12345".[5]

The 2016 film Suicide Squad reveals Gotham City to be in the state of New Jersey within the DC Extended Universe.[18][19]

In relation to Metropolis

Gotham City is the home of Batman, just as Metropolis is home to Superman, and the two heroes often work together in both cities. In comic book depictions, the exact distance between Gotham and Metropolis has varied over the years, with the cities usually being within driving distance of each other. The two cities are sometimes portrayed as twin cities on opposite sides of the Delaware Bay, with Gotham in New Jersey and Metropolis in Delaware.[2][4] The Atlas of the DC Universe from the 1990s places Metropolis in Delaware and Gotham City in New Jersey.[20]

New York City has also garnered the nickname Metropolis to describe the city in the daytime in popular culture, contrasting with Gotham, sometimes used to describe New York City at night.[21] During the Bronze Age of Comic Books, the Metro-Narrows Bridge was depicted as the main route connecting the twin cities of Metropolis and Gotham City.[22][23] It has been described as being the longest suspension bridge in the world.[24]

A map appeared in The New Adventures of Superboy #22 (October 1981), that showed Smallville within driving distance of both Metropolis and Gotham City; Smallville was relocated to Kansas in post-Crisis continuity.[25] A map of the United States in The Secret Files & Origins Guide to the DC Universe 2000 #1 (March 2000) depicts Metropolis and Gotham City as being somewhere in the Tri-state Area alongside Blüdhaven.[26]

Within the DC Extended Universe, the 2016 film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice depicts Gotham City as being located across a bay from Metropolis.[27]

History

A Norwegian mercenary, Captain Jon Logerquist, founded Gotham City in 1635 and the British later took it over—a story that parallels the founding of New York by the Dutch (as New Amsterdam) and later takeover by the British.[28] During the American Revolutionary War, Gotham City was the site of a major battle (paralleling the Battle of Brooklyn in the American Revolution). This was detailed in Rick Veitch's Swamp Thing #85 featuring Tomahawk. Rumours held it to be the site of various occult rites.

The 2011 comic book series Batman: Gates of Gotham details a history of Gotham City in which Alan Wayne (Bruce Wayne's ancestor), Theodore Cobblepot (Oswald Cobblepot's ancestor), and Edward Elliot (Thomas Elliot's ancestor), are considered the founding fathers of Gotham. In 1881, they constructed three bridges called the Gates of Gotham, each bearing one of their last names. Edward Elliot became increasingly jealous of the Wayne family's popularity and wealth during this period, jealousy that would spread to his great-great-grandson, Thomas Elliot or Hush.[29]

The occult origins of Gotham are further delved into by Peter Milligan's 1990 story arc "Dark Knight, Dark City",[30] which reveals that some of the American Founding Fathers are involved in summoning a bat-demon which becomes trapped beneath old "Gotham Town", its dark influence spreading as Gotham City evolves. A similar trend is followed in 2005's Shadowpact #5 by Bill Willingham, which expands upon Gotham's occult heritage by revealing a being who has slept for 40,000 years beneath the land upon which Gotham City was built. Strega, the being's servant, says that the "dark and often cursed character" of the city was influenced by the being who now uses the name "Doctor Gotham."

During the American Civil War, Gotham was defended by an ancestor of the Penguin, fighting for the Union Army, Col. Nathan Cobblepot, in the Legendary Battle of Gotham Heights. In Gotham Underground #2 by Frank Tieri, Tobias Whale claims that 19th century Gotham was run by five rival gangs, until the first "masks" appeared, eventually forming a gang of their own. It is not clear whether these were vigilantes or costumed criminals.

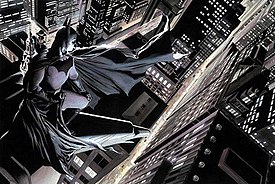

In contemporary times, Batman is considered the protector of Gotham, as he is fiercely protective of his home city. While other masked vigilantes also operate in Gotham City, they do so under Batman's approval since he is considered the best and most knowledgeable crime-fighter in the city.

Many storylines have added more events to Gotham's history, at the same time greatly affecting the city and its people. Perhaps the greatest in effect was a long set of serial storylines, which started with Ra's al Ghul releasing a debilitating virus called the "Clench" during the Contagion storyline. As that arc concluded, the city was beginning to recover, only to suffer an earthquake measuring 7.6 on the Richter Scale in the 1998 "Cataclysm" storyline. This resulted in the federal government cutting Gotham off from the rest of the United States in the 1999 storyline "No Man's Land", the city's remaining residents forced to engage in gang warfare, either as active participants or paying for protection from groups ranging from the GCPD to the Penguin, just to stay alive. Eventually, Gotham was rebuilt and returned to the U.S. as part of a campaign mounted by Lex Luthor, who used the positive publicity of his role to make a successful bid for the position of President of the United States.

For a time, the city faces various complications from gang warfare and escalating vigilante actions, due to such events as Spoiler unintentionally triggering a gang war, the return of Jason Todd as the Red Hood, and Bruce Wayne's disappearance during the war against Darkseid. Although Dick Grayson takes on the role of Batman for a time, matters become worse when a complex conspiracy initiated by the Cluemaster results in multiple villains attacking all areas of Batman's life, ruining the reputation of Wayne Enterprises and seeing Commissioner Gordon framed for causing a mass train accident. After the destruction caused by the Joker's latest rampage, new villain Mr Bloom sets out to destroy the city so that a new form can "grow" from it, but Bruce Wayne returns as Batman in time to defeat Bloom and reaffirm his role as Batman.

Suggestions of other Gotham City histories include a founding date of 1820 seen in a city seal in Batman: Return of the Caped Crusaders.

Culture

Batman writer and editor Dennis O'Neil has said that, figuratively, Batman's Gotham City is akin to "Manhattan below Fourteenth Street at eleven minutes past midnight on the coldest night in November."[31] Batman artist Neal Adams has long believed that Chicago has been the basis for Gotham, stating "one of the things about Chicago is Chicago has alleys (which are virtually nonexistent in New York). Back alleys, that's where Batman fights all the bad guys."[32] The statement "Metropolis is New York in the daytime; Gotham City is New York at night" has been variously attributed to comics creators Frank Miller and John Byrne.[33]

In designing Batman: The Animated Series, creators Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski emulated the Tim Burton films' "otherworldly timelessness," incorporating period features such as black-and-white title cards, police airships (although no such thing existed, Timm has stated that he found it to fit the show's style), and a "vintage" color scheme with film noir flourishes.[35] Police airships have since been incorporated into Batman comic books and are a recurring element in Gotham City.[34]

Concerning the evolution of Gotham throughout the years, Paul Levitz, Batman editor and former DC Comics president, has stated "each guy adds their own vision. That's the fun of comics, rebuilding a city each time.[36]"

Architecture

In the Batman comics, the person cited as an influential figure in promoting the unique architecture of Gotham City during the 19th century was Judge Solomon Wayne, Bruce Wayne's ancestor. His campaign to reform Gotham came to a head when he met a young architect named Cyrus Pinkney. Wayne commissioned Pinkney to design and to build the first "Gotham Style" structures in what became the center of the city's financial district. The "Gotham Style" idea of the writers matches parts of the Gothic Revival in style and timing. In the story line of Batman: Gothic, the Gotham Cathedral plays a central role for the story as it is built by Mr Whisper, the story's antagonist.

In a 1992 storyline, a man obsessed with Pinkney's architecture blew up several Gotham buildings in order to reveal the Pinkney structures they had hidden; the editorial purpose behind this was to transform the city depicted in the comics to resemble the designs created by Anton Furst for the 1989 Batman film.[38][39][40] Alan Wayne expanded upon his father's ideas and built a bridge to expand the city. Edward Elliot and Theodore Cobblepot also each had a bridge named for them.

Batman Begins features a CGI-augmented version of Chicago while The Dark Knight more directly features Chicago infrastructure and architecture such as Navy Pier. However, The Dark Knight Rises abandoned Chicago, instead shooting in Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, New York City, Newark, New Jersey, London and Glasgow.[41][42][43][44][45][46]

Education

Gotham Academy has appeared in different comics and shows, as the most prestigious private school in Gotham. Richard Grayson, and Damian Wayne have both attended the school.

Gotham City University is a major college located in the city. In the DC Extended Universe, Victor Stone attended the University prior to turning into Cyborg.

Notable residents

Bruce Wayne's place of residence is Wayne Manor, which is located on the outskirts of the city. His butler, Alfred Pennyworth, aids Bruce in his crusade to fight crime in Gotham.

Over the years, in various Bat titles in the chronological DC Comics continuity, the caped crusader enlists the help of numerous characters, the first being his trusty sidekick, Robin. Although a singular title, many have donned the mantle of the Boy Wonder over the years. The first being Nightwing, then came Red Hood, Red Robin (comics), and finally Batman's son Damian Wayne. In addition to the Robins or former Robins, there is also Catwoman, Batgirl, and Huntress (comics).

Other DC characters have also been depicted to be living in Gotham, such as mercenary Tommy Monaghan[47] and renowned demonologist Jason Blood. Within modern DC Universe continuity, Batman is not the first hero in Gotham. Stories featuring Alan Scott, the Golden Age Green Lantern, set before and during World War II depict Scott living in Gotham, and later depictions show him running his Gotham Broadcasting Corporation.[48] Also, the original Golden Age Spectre and his sidekick, Percival Popp, live in Gotham City[49] as does Starman[50] and the Gay Ghost.[51]

DC's 2011 reboot of All Star Western takes place in an Old West-styled Gotham. Jonah Hex and Amadeus Arkham are among this version of Gotham's inhabitants.[52]

Apart from Gotham's superhero residents, the residents of the city feature in a back-up series in Detective Comics called Tales of Gotham City[53] and in two limited series called Gotham Nights. Additionally, the Gotham City Police Department is the focus of the series Gotham Central, as well as the mini-series Gordon's Law, Bullock's Law, and GCPD.

Due to the volatile nature of Gotham politics, turnover of mayors and other city officials is high. The first Gotham mayor depicted in comics was unnamed, but appeared as a caricature of New York mayor Fiorello La Guardia.[54][55] Theodore Cobblepot, great grandfather of the Penguin, was mayor in the late nineteenth century.[56] An unnamed mayor ran afoul of the Court of Owls in 1914 and was killed by them.[57] Archibald Brewster was mayor during the Great Depression.[58] Mayor Thorndike was killed by the Made of Wood killer in 1948.[59] Mayor Aubrey James was a contemporary of Thomas Wayne who was stabbed to death.[60] Mayor Jessop was in office shortly after the Wayne murders.[61] A man named Falcone was purportedly mayor during the earliest days of Batman's career.[62] Shortly after, Mayor Wilson Klass directed the GCPD to turn a blind eye to Batman's activities after Batman saved his daughter.[63] Mayor Hill was in office when the Joker debuted,[64] and a man named Gill was mayor early in Batman's career,[65] as was former police commissioner Grogan.[66] An unnamed bald mayor was killed by a villain known as Midnight.[67]

Men named Carfax,[68] Bradley Stokes,[69] Sheppard,[70] Taylor,[71] and Hayes[72] all served as mayor. Mayor Charles Chesterfield was killed by a sentient fat-eating blob of grease.[73] Hamilton Hill became mayor through the backing of crime boss Rupert Thorne but was ultimately ousted from office[74] and replaced by George P. Skowcroft.[75] An unnamed mayor is killed by Deacon Blackfire's followers and replaced by Donald Webster.[76] Mayor Julius Lieberman is killed by a Predator.[77] Mayor Goode served briefly[78] before being replaced by an African American man.[79] Armand Krol became mayor[80] and died of the Clench virus after leaving office.[81] A woman, Marion Grange, became mayor with the backing of Bruce Wayne but was assassinated in Washington, D.C. while trying to secure federal aid for Gotham after an earthquake.[82] In the wake of No Man's Land, Daniel Danforth Dickerson III served as mayor only to be killed by a sniper, after which he was replaced by David Hull.[83] Seamus McGreevy served as mayor in the midst of a criminal conspiracy known as "The Body".[84] An unnamed woman was mayor when Batman returned to Gotham a year after the Infinite Crisis.[85] Sebastian Hady was a corrupt mayor who was eventually killed by the League of Shadows.[86] Councilwoman Muir served as interim mayor when the city was in the grip of a virus that only affected men.[87] Michael Akins, former commissioner of police, was appointed mayor,[88] and later replaced by a man named Atkins.[89] In the wake of Bane's takeover of the city, the current mayor in DC Comics continuity is a man named Dunch.[90]

Gotham City Police Department

Cartography of Gotham City by Eliot R. Brown.

In other media

Television

The 1960s live-action Batman television series never specified Gotham's location though there are hints it actually represents New York City, including a city map and its location across the 'West River' from 'Guernsey City' in 'New Guernsey'. Fictional residents Mayor Linseed (portrayed by Byron Keith) and Governor Stonefellow are also direct allusions to real-life Mayor John Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller. The related theatrical movie showed Batman to be flying over suburban Los Angeles, the Hollywood Hills, palm trees, a harbor, a beach and a view of the Los Angeles City Hall.

Gotham City is featured in Batman: The Animated Series. When describing Gotham City Paul Dini, a writer and director of the show, stated "in my mind, it was sort of like what if the 1939 World's Fair had gone on another 60 years or so.[91]" In the episode "Joker's Favor", a driver's license lists a Gotham area resident's hometown as "Gotham Estates, NY". In the episode "Avatar", when Bruce Wayne leaves for England, a map shows Gotham City, at the joining of Long Island and the Hudson River. The episode "Fire from Olympus" shows a character's address in a police file indicating that Gotham City is located in New York state. The episode "The Mechanic", however, implies that Gotham resides in a state of the same name; a prison workshop is shown stamping license plates that read "Gotham: The Dark Deco State" (as a reference to the artistic style of the series). The episode "Harlequinade" states that Gotham City has a population of approximately 10 million people. This figure was also given in the 1960s Batman TV series episode "Egg Grows in Gotham", the thirteenth episode of the second season.

The live-action TV series Gotham is filmed in New York City and was an important requirement of the show's creative team.[91] According to executive producer Danny Cannon, its atmosphere is inspired by the look of the city itself in the 1970s films of Sidney Lumet and William Friedkin. Clues to this include and signs showing phone numbers bearing the area code 212.[92] Donal Logue, who portrays Harvey Bullock in the series Gotham, described different aspects of that series' design of Gotham City as exhibiting different sensibilities, explaining, "for me, you can step into things that almost feel like the roaring 20s, and then there's this other really kind of heavy Blade Runner vibe floating around. There are elements of it that are completely contemporary and there are pieces of it that are very old-fashioned...There were a couple of examples of modern technology, but maybe an antiquated version of it, that gave me a little bit of sense that it's certainly not the 50s and the 60s...But it's not high tech and it's not futuristic, by any means."[93]

In the TV series Smallville, Gotham City is mentioned by the character Linda Lake in the episode "Hydro", who jokes she can see Gotham from her view. It is also mentioned in "Reunion", where one of Oliver Queen's friends mentions having to get back to Gotham.

The fifth episode of Young Justice, entitled Schooled, indicates that Gotham is located in Connecticut, near Bridgeport.

Arrowverse

Gotham City was first shown in the Arrowverse as part of Elseworlds, a 2018 crossover storyline among the shows, which introduced Batwoman, although it had been referenced several times previously.[94] For the TV series Batwoman, both Vancouver and Chicago were used for Gotham City. In this show, the Crows have helped to defend it from crime ever since Batman went missing three years ago.

In The Flash episode "Marathon", a map sites Gotham City in place of Chicago, Illinois.

Films

1989 Batman series

Batman (1989) director Tim Burton wanted a timeless alternate to New York and described it as "hell burst through the pavement and grew".[91] The look of Gotham was overseen by production designer Anton Furst, who won an Oscar for supervising the art department.[95] Furst stated Batman was "definitely based in many ways on the worst aspects of New York City" and was inspired by Andreas Feininger's photographs of 1940s New York.[8] Furst's draftsman Nigel Phelps created numerous charcoal drawings of the buildings and interior sets for the production.

Following the death of Furst, Burton tapped Bo Welch to oversee production design for Batman Returns (1992). Burton wanted Welch to re-imagine Gotham, stating "Batman didn't feel big to me – it didn't have the power an old American city has".[96] Welch wanted to expand on the same basic concept for the sequel but moved away from European influences to show more American Art Deco/world's fair elements.[95][97] When asked what inspired his interpretation of Gotham, Welch stated "[H]ow can I create a visual expression of corruption and greed? That got me thinking about the fascistic architecture employed at world's fairs... That feels corrupt because it's evocative of oppressive bureaucracies and dictatorships... So I looked at a lot of [Third Reich] art and images from world's fairs".[96] To physically make the city seem darker, he designed tall "oppressively overbuilt" cityscape that physically blocked out light.[95][96]

When Joel Schumacher took over directing the Batman film series from Tim Burton, Barbara Ling handled the production design for both of Schumacher's films Batman Forever (1995)[98][99][100] and 1997's Batman & Robin.[101][102][103] Ling's vision of Gotham City was a luminous and outlandish evocation of Modern expressionism[104] and Constructivism.[105] Its futuristic-like concepts (to a certain extent, akin to the 1982 film Blade Runner[106]) appeared to be sort of a cross between 1930's Manhattan and the "Neo-Tokyo" of Akira. Ling admitted her influences for the Gotham City design came from "neon-ridden Tokyo and the Machine Age. Gotham is like a World's Fair on ecstasy."[107] When Batman is pursuing Two-Face in Batman Forever, the chase ends at Lady Gotham, the fictional equivalent of the Statue of Liberty. During Mr. Freeze's attempt to freeze Gotham in the film Batman & Robin, the targeting screen for his giant laser locates it somewhere on the New England shoreline, possibly as far north as Maine. The soundtrack for Batman & Robin features a song named after the city and sung by R. Kelly, later included on international editions of his 1998 double album R.

The Dark Knight Trilogy

Director Christopher Nolan has stated that Chicago is the basis of his portrayal of Gotham, and the majority of both Batman Begins (2005) and The Dark Knight (2008) were filmed there.[32] However, the city itself seems to take many cues from New York City: police cars use a paint job that was used by the NYPD in the 1990s, and the same is applicable to garbage trucks, and the Gotham Post seems to have the same font heading as The New York Post.

In Batman Begins, Nolan desired that Gotham appeared as a large, modern city that nonetheless reflected a variety of architecture styles and periods, as well as different socioeconomic strata. The production's approach depicted Gotham as an exaggeration of New York City, with elements taken from Chicago, the elevated freeways and monorails of Tokyo,[10] and the "walled city of Kalhoon" [sic] in Hong Kong, which was the basis for the slum in the film known as The Narrows.[9][10]

In the animated Batman: Gotham Knight (2008), which takes place between Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, The Narrows was converted into an expansion of Arkham Asylum.

In The Dark Knight, more Chicago and New York influences were observed. On filming in Chicago, James McAllister, key location manager stated, "visually it's that look like you would see in the comic books." Nolan also stated "there's all these different boroughs, with rivers to interconnect. I think it's hard to get away from that, because Gotham is based on New York."[32] In the movie, it is revealed that downtown Gotham, or much of the city, is on an island, similar to New York City's Manhattan Island, as suggested by the Gotham Island Ferry. However, while Gordon is discussing evacuation plans with the Mayor, land routes to the east are mentioned. In conversation with Harvey Dent, Bruce Wayne indicates that the Palisades of the Wayne Manor estate are within the city limits. In terms of population, Lucius Fox says that the city houses "30 million people." The film indicates that the city's area code is 735, which in real life is an unused code. Compared to the previous film, less CGI was used in Gotham's skyline, resulting in plenty of shots of a digitally unaltered Chicago skyline.

For The Dark Knight Rises (2012), the production utilized Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, New York City, Newark, New Jersey, London and Glasgow for shots of Gotham City.[41][42][43][44] [45][46] An address by the president refers to Gotham City as "America's greatest city," combined with a map seen briefly onscreen, confirms that Gotham (which looks more like Manhattan than Chicago, the city that stood in for Gotham in the previous two films) is an analogue to New York City within the movie's universe. The overview image of "Gotham Island" seen when the bridges are being blown is an aerial view of Manhattan with three bridges digitally added in on the Hudson River side. A state trooper on the last remaining intact bridge into the city is shown to be part of the "Gotham State Police," and a Gotham State Police car is among the vehicles that participate in the car chase after Bane's attack on the Stock Exchange, suggesting that Gotham City is in the fictional US state of Gotham.

DC Extended Universe

Within the DC Extended Universe, Gotham City is located in Gotham County, New Jersey. In Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, paperwork mentions that the city is in "Gotham County," and Amanda Waller's files on Deadshot and Harley Quinn in Suicide Squad reveal Gotham City to be located in the state of New Jersey.[18][19]

Zack Snyder confirmed that Metropolis and Gotham City are in close geographical proximity to each other,[108] with Gotham City being located on the edge of the New Jersey, separated from the federal district[109] of Metropolis by Delaware Bay. In Justice League it is revealed there is a tunnel connecting the two, constructed as part of the abandoned 'Metropolis Project' in 1929 to connect the two cities. There are multiple islands located in the bay also, with one of them being named Braxton Island. Senator Debbie Stabenow makes a cameo appearance in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice as the state's governor.

The Boston Globe compared the close proximity of Gotham and Metropolis to Jersey City, New Jersey and Manhattan, New York.[110] A television spot for Turkish Airlines premiering during the 2016 Super Bowl featured Bruce Wayne (played by the film's star, Ben Affleck) promoting Gotham as a tourist destination.[111]

To create Gotham in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the creative team "decided to recreate and combine large sections of existing selected city sections and adapt the architecture and layout to fit Gotham's. Thousands of photographs were put through MPC's photogrammetry pipeline to create geometry and textures for each city section.[112]"

DC Black

Joker director and producer Todd Phillips imagined Gotham as a "version of Gotham was the pre-’80s boom New York, or urban northeastern center, but not the iconic New York." When asked how he re-imagined the city, production designer Mark Friedberg stated "our version of Gotham was what groomed him. It was both an appreciation for how severe things got in the city, but also for the world of possibility that lived in the version of that city."[113]

Animated films

During the events of the direct-to-video film, Batman & Mr. Freeze: SubZero (1998), a computer screen displaying Barbara Gordon's personal information refers to her location as "Gotham City, NY", and also displays her area code as being 212 – a Manhattan area code. Batman Beyond (1999–2001) envisions a Gotham City in 2039, referred to as "Neo-Gotham".

The 2008 direct-to-DVD film Batman: Gotham Knight shows Gotham as a large city with many skyscrapers and a bustling population.

Video games

Gotham City appears in several video games, including Batman Begins, DC Universe Online, and Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe. The city makes another appearance in a video game with Injustice: Gods Among Us, where the player can fight in front of and inside of Wayne Manor, on top of a building and in an alley as well. Gotham also appears in Lego Dimensions, and it is a playable stage on Batman: Arkham universe

Batman: Arkham

Batman: Arkham Asylum (2009) opens with Batman driving Joker from Gotham City to Arkham Asylum. Joker also threatens to detonate bombs across Gotham. In Batman: Arkham City (2011), the slums of Old Gotham City (the northern island) were converted into Arkham City. Inside the prison walls, this part of Gotham contains various landmarks throughout the story, like Penguin's Iceberg Lounge, the Ace Chemical Plant, the Sionis Steel Mill, the Old Gotham City Police Department building, and the Monarch Theatre with the Wayne murder scene in Crime Alley. Most of these locations have major events in the story. In Batman: Arkham Origins (2013), an earlier, younger version of the city can be seen than that of other games in the Batman: Arkham series. In addition to the northern island, this installment in the series lets players explore a new southern island, connected to the former by the Pioneer's Bridge. The setting of Batman: Arkham Knight (2015), Central Gotham City, is five times larger than Old Gotham.

References

- ^ a b Amazing World of DC Comics #14, March 1977. DC Comics.

- ^ a b World's Finest Comics #259, October–November 1979. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #503 June 1983. DC Comics.

- ^ a b Atlas of the DC Universe, 1990. DC Comics.

- ^ a b Batman: Shadow of the Bat Annual #1, June 1993. DC Comics.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Paul (May 18, 2011). "The Secret Geography of the DC Universe: A Really Big Map"

- ^ Safire, William (July 30, 1995). "ON LANGUAGE; Jersey's Vanishing 'New'". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Hanson, Matt (2005). Building Sci-fi Moviescapes: The Science Behind the Fiction. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-240-80772-0.

- ^ a b "Film locations for Batman Begins". Movie-locations.com. Archived from the original on April 23, 2019. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c Otto, Jeff (June 5, 2006). "Interview: Christopher Nolan". IGN. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2006.

- ^ Steranko, Jim (1970). The Steranko History of Comics. Reading, PA: Supergraphics. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-517-50188-7.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. (Oxford University Press, 1999), 417.

- ^ "Gotham". World Wide Words. February 6, 1999. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Lowbridge, Caroline (January 1, 2014). "The real Gotham: The village behind the Batman stories". BBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ World's Greatest Super Heroes, August 1978. DC Comics.

- ^ World's Finest Comics #259, October–November 1979

- ^ New Adventures of Superboy #14, October 1981. DC Comics.

- ^ a b "Review: 'Suicide Squad'". Asbury Park Press. August 5, 2016.

- ^ a b ""Suicide Squad": The Biggest Revelations From The Latest DC Film". comicbookresources.com. August 7, 2016.

- ^ Montgomery, Paul (May 18, 2011). "The Secret Geography of the DC Universe: A Big Map". iFanboy.

- ^ Keri Blakinger (March 8, 2016). "From Gotham to Metropolis: A look at NYC's best nicknames". Daily News. New York. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ DC Comics Presents #18, February 1980

- ^ New Adventures of Superboy #22, October 1981

- ^ Action Comics #451, September 1975. DC Comics.

- ^ The Man of Steel #1, October 1986. DC Comics.

- ^ Secret Files & Origins Guide to the DC Universe 2000 #1 (March 2000)

- ^ "'Batman v Superman': Are Metropolis and Gotham City that close?". March 25, 2016.

- ^ Atlas of the DC Universe. Mayfair Games.

- '^ Batman: Gates to Gotham, May 2011. DC Comics.

- ^ Burgas, Greg (April 13, 2010). "Dark Knight, Dark City". Comic Book Resources.

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis. Afterword. Batman: Knightfall, A Novel. New York: Bantam Books. 1994. 344.

- ^ a b c "Dark Knight's kind of town: Gotham City". Today. Associated Press. July 20, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bopik, Barry (March 29, 2008). "The Big Apple: "Metropolis is New York by day; Gotham and Metropolis is New York". Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Batman vol. 2 #2, December 2011. DC Comics.

- ^ Bruce Timm and Eric Radomski, audio commentary for "On Leather Wings", Batman: The Animated Series, Warner Bros, Volume One box set DVD.

- ^ Bros, Warner (July 20, 2008). "Dark Knight's kind of town: Gotham City". TODAY.com. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ Travel (February 27, 2008). "Helsinki: a cruiser's guide". Telegraph. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (a). "The Destroyer Part One: A Tale of Two Cities" Batman, no. 474 (February 1992). DC Comics.

- ^ Grant, Alan (w), Sprouse, Chris, Anton Furst (p), Patterson, Bruce (i). "The Destroyer Part Two: Solomon" Legends of the Dark Knight, no. 27 (February 1992). DC Comics.

- ^ Grant, Alan (w), Aparo, Jim (p), DeCarlo, Mike (i). "The Destroyer Part Three" Detective Comics, no. 641 (February 1992). DC Comics.

- ^ a b "Juicy Plot Details Revealed as The Dark Knight Rises Moves to Pittsburgh". Reelz Channel. June 12, 2011. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Vancheri, Barbara (August 21, 2011). "Fans glimpse final round of 'Dark Knight' filming". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Wigler, Josh (February 15, 2012). "'Dark Knight Rises' Meets... Donald Trump?". MTV. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Gridlock in Gotham: 'Dark Knight' filming in Newark likely to cause massive traffic delays this week", The Star-Ledger, November 2, 2011, retrieved November 5, 2011

- ^ a b "'The Dark Knight Rises' to film in Newark", New York Post, November 3, 2011, retrieved November 5, 2011

- ^ a b Di Ionno, Mark (November 5, 2011). "Di Ionno: Trying to unmask Newark's secret identity as a Batman film location". The Star-Ledger.

- ^ Ennis, Garth (w). John McCrea (a). "A Rage in Arkham". Hitman. April 1996. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #784–786. DC Comics.

- ^ More Fun Comics #94. DC Comics.

- ^ Adventure Comics #89. DC Comics.

- ^ Sensation Comics #25. DC Comics.

- ^ Palmiotti, Jimmy; Gray, Justin (w); Moritat (a). All Star Western Vol. 1: Guns and Gotham (November 6, 2012). DC Comics. (Reprints issues 1–6).

- ^ Detective Comics #488–490, 492, 494, 495, 504, 507. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman #12. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #68. DC Comics.

- ^ Gotham Underground. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman and Robin #23.2. DC Comics.

- ^ Daily Planet Guide to Gotham City. West End Games.

- ^ Detective Comics #784-786. DC Comics.

- ^ Legends of the Dark Knight 204-206. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: The Return of Bruce Wayne #5. DC Comics.

- ^ Secret Origins #50. DC Comics.

- ^ Legends of the Dark Knight #11-15. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman Confidential #24. DC Comics

- ^ Legends of the Dark Knight #169-171. DC Comics.

- ^ Two-Face: Year One #2. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: Gotham After Midnight #7. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #121. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #179. DC Comics.

- ^ World's Finest Comics #69. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #375. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman #207. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: Gotham Knights #18. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman #381

- ^ Detective Comics #551.

- ^ Batman: The Cult. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman Versus Predator. DC Comics/Dark Horse Comics.

- ^ Robin II #3. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #648. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: Shadow of the Bat #7-9. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #699. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: Road to No Man's Land. DC Comics.

- ^ Gotham Central #12. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman: City of Crime. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #817. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #951. DC Comics.

- ^ Batgirl and the Birds of Prey #15-17. DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #969. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman vs. Ra's al Ghul #1. DC Comics.

- ^ Batman Vol. 3 #86. DC Comics.

- ^ a b c "Gotham: The Evolution of Batman's Hometown". Den of Geek. May 4, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "Gotham: The Legend Reborn Preview Special: Behind The Shadows (Part 3)". Fox Broadcasting Company. Retrieved August 30, 2014.

- ^ Hankins, Brent (February 18, 2014). "Interview: Donal Logue talks conflict and character development in 'Gotham.'". Nerd Repository. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (May 17, 2018). "Batwoman to Make in 'Arrow'-verse Debut in Next Crossover". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Daly, Steve (June 19, 1992). "Sets Appeal: Designing 'Batman Returns'". Ew.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c Luis, Eric (October 30, 2019). "The Many Inspirations For Every Onscreen Portrayal Of Gotham City". Ranker. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 14, 1992). "Review: "Batman Returns"". Variety.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

Lensed seemingly entirely indoors or on covered sets, pic is a magnificently atmospheric elaboration on German expressionism. Its look has been freshly imagined by production designer Bo Welch, based on the Oscar-winning concepts of the late Anton Furst in the first installment. Welch's Gotham City looms ominously over all individuals, and every set-from Penguin's aquarium-like lair and Shreck's lavish offices to Bruce Wayne's vaguely "Citizen Kane"-like mansion and simple back alleys-is brilliantly executed to maximum evocative effect

- ^ "Film locations for Batman Forever". Movie-locations.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Batman Forever – Gotham". Angelfire.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ In collaboration with production designer Barbara Ling and her crew, Schumacher has kept the series' dark and monumental look (the legacy of Frank Miller's graphic novel "Batman: The Dark Knight Returns") and, as advertised, lightened the project's overall tone. Archived June 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Film locations for Batman & Robin". Movie-locations.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Batman & Robin – Gotham City". Angelfire.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Barbara Ling's no-holds-barred production design makes Gotham look more surreal than ever". Shoestring.org. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ "Batman & Robin's look is luminous and marvelously outlandish throughout. Barbara Ling's production design is outstanding, a stunning evocation of modern Expressionism". Members.aol.com. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- ^ Batman & Robin DVD extras

- ^ Departing from former "Batman" director Tim Burton's gothic approach to New York, Schumacher and production designer Barbara Ling compulsively layer the background with a futuristic city design that seems to aim for "Blade Runner" by way of "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles".

- ^ Barbara Ling, Bigger, Bolder, Brighter: The Production Design of Batman & Robin. 2005. Warner Home Video

- ^ "Zack Snyder Turned Gotham City and Metropolis into the Bay Area". Wired. July 11, 2015.

- ^ "It's Capes, Cowls, and Scowls in Our 'Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice' Gallery".

- ^ "‘Batman v Superman’ is dark and chaotic" by Ty Burr, Boston Globe, March 24, 2016

- ^ "'Batman v Superman': Gotham and Metropolis Detailed in New Promo".

- ^ "Batman V Superman Concept Art: Early Doomsday & Gotham City Designs". ScreenRant. February 13, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "The Design of 'Joker' Just Might Make You Sympathize With the Villain". www.backstage.com. September 25, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

Sources

- Brady, Matthew and Williams, Dwight. Daily Planet Guide to Gotham City. Honesdale, Pennsylvania: West End Games under license from DC Comics, 2000.

- Brown, Eliot. "Gotham City Skyline". Secret Files & Origins Guide to the DC Universe 2000. New York: DC Comics, 2000.

- Grant, Alan. "The Last Arkham". Batman: Shadow of the Bat #1. New York: DC Comics, 1992.

- Loeb, Jeph. Batman: The Long Halloween. New York: DC Comics, 1997.

- Miller, Frank. Batman: Year One. New York: DC Comics, 1988.

- Morrison, Grant. Arkham Asylum. New York: DC Comics, 1990.

- O'Neil, Dennis. "Destroyer". Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #27. New York: DC Comics, 1992.

Template:Timeline may refer to:

- {{For timeline}}

- {{Navbox timeline}}

- {{Include timeline}}

- {{Timeline Legend}}

- {{Prose timeline}}

- {{Sidebar timeline}}

- {{Timeline of release years}}

- {{Timeline-start}}

- {{Timeline-item}}

- {{Timeline-end}}

- {{Timeline-event}}

- {{Timeline-links}}

{{Template disambiguation}} should never be transcluded in the main namespace.