Harakiri (1962 film)

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (October 2018) |

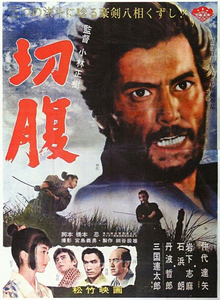

| Harakiri | |

|---|---|

Japanese theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Masaki Kobayashi |

| Screenplay by | Shinobu Hashimoto[1] |

| Based on | "Ibunronin ki" by Yasuhiko Takiguchi |

| Produced by | Ginichi Kishimoto[1] |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Yoshio Miyajima[1] |

| Edited by | Hisashi Sagara[1] |

| Music by | Toru Takemitsu[1] |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Shochiku |

Release date |

|

Running time | 134 minutes[1] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Harakiri (切腹, Seppuku[2], 1962) is a 1962 Japanese jidaigeki period drama film directed by Masaki Kobayashi. The story takes place between 1619 and 1630 during the Edo period and the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. It tells the story of Hanshirō Tsugumo, a warrior without a lord.[3] At the time, it was common for masterless samurai, or rōnin, to request to commit seppuku (harakiri) in the palace courtyard in the hope of receiving alms from the remaining feudal lords.

Plot

Edo, 1630. Tsugumo Hanshirō arrives at the estate of the Ii clan and says that he wishes to commit seppuku within the courtyard of the palace. To deter him Saitō Kageyu (Rentarō Mikuni), the Daimyō's senior counselor, tells Hanshirō the story of another rōnin, Chijiiwa Motome – formerly of the same clan as Hanshirō.

Saito scornfully recalls the practice of ronin requesting the chance to commit seppuku on the clan's land, hoping to be turned away and given alms. Motome arrived at the palace a few months earlier and made the same request as Hanshirō. Infuriated by the rising number of "suicide bluffs", the three most senior samurai of the clan—Yazaki Hayato, Kawabe Umenosuke, and Omodaka Hikokuro—persuaded Saitō to force Motome to follow through and kill himself. Upon examining Motome's swords, his blades were found to be made of bamboo. Enraged that any samurai would "pawn his soul", the House of Ii forced Motome to disembowel himself with his own bamboo blade, making his death slow, agonizingly painful, and deeply humiliating.

Despite this warning, Hanshirō insists that he has never heard of Motome and says that he has no intention of leaving the Ii palace alive. After a suicide pavilion is set up in the courtyard of the palace, Hanshirō is asked to name the samurai who shall behead him when the ritual is complete. To the shock of Saitō and the Ii retainers, Hanshirō successively names Hayato, Umenosuke, and Hikokuro—the three samurai who coerced the suicide of Motome. When messengers are dispatched to summon them, all three decline to come, saying they are suffering from a life-threatening illness.

After provoking their laughter by calling bushido a facade, Hanshirō recounts his story to Saitō and the Ii retainers. He did, he admits, know Motome after all. In 1619, his clan was abolished by the Shōgun. His Lord decided to commit seppuku and, as his most senior samurai, Hanshirō planned to die alongside him. To prevent this, Hanshirō's closest friend performed seppuku and left a letter assigning to Hanshirō the guardianship of his teenage son—Motome. Despite Hanshirō's pleas, his Lord forbade him to kill himself.

In order to support Motome and his own daughter Miho, Hanshirō rented a hovel in the slums of Edo and was reduced to making paper umbrellas to make ends meet. Despite this, he retained a firm sense of personal and familial honor. Realizing the love between Motome and Miho, Hanshirō arranged for them to marry. Soon after, they had a son, Kingo.

When Miho fell ill with a fever, Motome could not bear the thought of losing her and did everything to raise money to hire a doctor. When Kingo also fell ill, Hanshirō was enraged when Motome claimed to have already sold everything of value. Motome, however, calmly explained that there was another way to raise money and that he would return very soon. For hours, Hanshirō and Miho anxiously awaited his return. Late that evening, Hayato, Umenosuke, and Hikokuro had brought Motome's mutilated body home. They explained how Motome had come to the Ii palace and had been forced to kill himself. They then displayed his bamboo blades in order to mock their victim before his family. After they left, Miho spent hours weeping inconsolably over her husband's body. Then, she returned to her sickbed next to Kingo. Having had no idea that Motome had sold even his sword blades to save Miho, a devastated Hanshirō implored his son-in-law's forgiveness for his own carelessness. Soon after, Kingo died from his illness. Having already lost the will to live, Miho followed after him the next day.

Completing his story, Hanshirō explains that his sole desire is to join Motome, Miho, and Kingo in the next world. He explains, however, that they have every right to ask whether justice has been exacted for their deaths. Therefore, Hanshiro asks Saito if he has any statement of regret to convey to Motome, Miho, and Kingo. He explains that, if Saito does so, he will die without saying another word.

Saitō, however, insists that Motome was "a despicable extortioner" who got exactly what he deserved. He boasts that all other suicide bluffs who come to the Ii palace shall be treated in the same fashion.

Hanshirō then reveals the last part of his story. Before coming to the Ii house, he had tracked down Hayato and Umenosuke, easily defeated them, and cut off their topknots. Hikokuro then came to Hanshirō's hovel and, with great respect, challenged him to a duel. After a brief but tense sword fight, Hikokuro suffers a double disgrace: his sword is broken and his topknot was taken as well. As proof of his story, Hanshiro removes their labelled topknots from his kimono and casts them upon the palace courtyard.

With deep contempt, Hanshiro reminds everyone that, for a samurai to lose his topknot is a disgrace so horrendous that even suicide can barely atone for it. And yet, the most revered samurai of the House of Ii —Hayato, Umenosuke, and Hikokuro— lack the fortitude to commit the suicide they would demand from anyone else. Instead, they are concealing their dishonor, feigning illness, and waiting for their hair to grow back. Hanshiro concludes that, despite the Ii clan's pride in its martial history, it seems that the Code of the Samurai is a facade even for them.

Having now lost face very badly, an enraged Saitō calls Hanshiro a madman and orders his remaining samurai to kill him. In a battle which rages through the palace, Hanshirō kills four samurai, wounds eight, and contemptuously throws down the antique suit of armor which symbolizes the glorious history of the House of Ii. In a final confirmation of the clan's Machiavellian ways, three Ashigaru arrive armed with matchlock guns—a weapon seen as beneath contempt. As Hanshirō begins seppuku, he is simultaneously shot by all three gunmen.

Terrified that the Ii clan will be abolished if word gets out that "a half starved ronin" killed so many of their retainers, Saito announces that all deaths caused by Hanshiro shall be explained by "illness". At the same time, a messenger returns reporting that Hikokuro had committed harakiri the day before, while Hayato and Umenosuke are lying about their illnesses. Saito angrily orders that Hayato and Umenosuke are to also commit seppuku as atonement for losing their topknots, and that a squad of soldiers are to be sent to their houses "to make sure they do it."

As the suit of armor is lovingly re-erected, the visitor's book of the House of Ii clan is heard in voiceover. Hanshiro, who was clearly mentally unstable, had to be forced, like Motome before him, to commit suicide. The Shōgun, it is said, has issued a personal commendation to the Ii clan for how they handled the suicide bluffs of Motome and Hanshiro. At the end of his letter, the Shōgun praises the House of Ii and their samurai as the perfection of the Code of Bushido. Janitors clean the grounds where the fighting had occurred, and a janitor finds one of the three severed top knots on the ground. He places it in a bucket.

Cast

- Tatsuya Nakadai - Tsugumo Hanshirō (津雲 半四郎)

- Rentarō Mikuni - Saitō Kageyu (斎藤 勘解由)

- Akira Ishihama - Chijiiwa Motome (千々岩 求女)

- Shima Iwashita - Tsugumo Miho (津雲 美保)

- Tetsurō Tamba - Omodaka Hikokuro (沢潟 彦九郎)

- Ichiro Nakatani - Yazaki Hayato (矢崎 隼人)

- Masao Mishima - Inaba Tango (稲葉 丹後)

- Kei Satō - Fukushima Masakatsu (福島 正勝)

- Yoshio Inaba - Chijiiwa Jinai (千々岩 陣内)

- Yoshiro Aoki - Kawabe Umenosuke (川辺 右馬介)

Themes

When asked about the theme of his film, Kobayashi said: "All of my pictures… are concerned with resisting an entrenched power. That’s what Harakiri is about, of course, and Rebellion as well. I suppose I've always challenged authority."[4]

Audie Bock describes the theme of Harakiri as "the inhumanity of this requirement for those who dutifully adhered to it, and the hypocrisy of those who enforced this practice."[5] The movie doesn't so much challenge the practise of seppuku, as highlight an instance when it occurred in a punitive and hypocritical environment. The notions of honor and bravery associated with it can be "a false front," as the hero puts it.

The empty suit of armor, shown in the beginning, symbolizes the past glory of the Ii clan, and is treated by them with reverence. However, the samurai of the Ii house behave like cowards in the fight with Tsugumo, who mockingly knocks the suit over and uses it to defend himself. Kobayashi makes a point here that this symbol of military prowess turns out to be an empty one.[6]

Kobayashi also attacks two other important attributes of the samurai rank: the sword and the topknot. Chijiwa finds out that the sword is of no use to him if he cannot provide for his family and get a medical help for his sick child. When Tsugumo takes his revenge on the three men complicit in Chijiwa’s death, he prefers divesting them of their topknots rather than killing them. At the time, losing one's topknot was the same as losing one's sword, and death would be preferable to such dishonor. But those three samurai cowardly take a leave of absence, and two of them are forced to commit suicide only when Tsugumo makes their humiliation public. Hikokuro Omodaka commit seppuku by his own choice. Thus his revenge is very subtle: he makes the clan to live by the rules they claim to uphold and which they used to punish Chijiwa.[7]

The daily record book of the clan that appears in the beginning and the end of the film "represents the recorded lies of history." It will only mention Tsugumo's suicide, and the entire story of his challenge to the clan will be purged from the record to protect the façade of "the unjust power structure."[8]

Release

Harakiri was released in Japan in 1962.[1] The film was released by Shochiku Film of America with English subtitles in the United States in December 1963.[1]

Reception

In a contemporary review, the Monthly Film Bulletin stated that Masaki Kobayashi's "slow, measured cadence perfectly matches his subject" and that the "story itself is beautifully constructed". The review praised Tatsuya Nakadai's performance as a "brilliant, Mifune-like performance" and noted that the film was "on occasion brutal, particularly in the young samurai's terrible agony with his bamboo sword" and that although "some critics have remarked [...] that being gory is not the best way to deplore wanton bloodshed, Harakiri still looks splendid with its measured tracking shots, its slow zooms, its reflective overhead shots of the courtyard, and its frequent poised immobility."[9] The New York Times reviewer Bosley Crowther was unimpressed with "the tortured human drama in this film" but added that "Mr. Kobayashi does superb things with architectural compositions, moving forms and occasionally turbulent gyrations of struggling figures in the CinemaScope-size screen. He achieves a sort of visual mesmerization that is suitable to the curious nightmare mood."[10] Cid Corman wrote in Film Quarterly that "the beauty of the film seems largely due to Kobayashi’s underlying firmness of conception and prevailing spirit, by an unevasive concern for cinematic values."[11]

Donald Richie called it the director's "single finest picture" and quoted Kobayashi's mentor Keisuke Kinoshita who named it among the top five greatest Japanese films of all time.[12] Audie Bock wrote: "Harakiri avoids the sentimentality of some of his earlier films, such as The Human Condition, through a new emphasis on visual-auditory aesthetics with the cold formality of compositions and Takemutsu's electronic score. But none of Kobayashi's social protests is diminished in the film's construction--it's Mizoguchi-like circularity bitterly denies any hope for human progress."[13] More recently Roger Ebert added Harakiri to his list of "Great Movies", writing in his 2012 review: "Samurai films, like westerns, need not be familiar genre stories. They can expand to contain stories of ethical challenges and human tragedy. Harakiri, one of the best of them, is about an older wandering samurai who takes his time to create an unanswerable dilemma for the elder of a powerful clan. By playing strictly within the rules of Bushido Code which governs the conduct of all samurai, he lures the powerful leader into a situation where sheer naked logic leaves him humiliated before his retainers."[14]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 100% rating based on eight critic reviews, with an average rating of 7.33/10.[15]

Awards

The film was entered in the competition category at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival. It lost the Palme d'Or to The Leopard, but received the Special Jury Award.[16]

Remakes

The film was remade by Japanese director Takashi Miike as a 3D film titled Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai. It premiered at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Galbraith IV 1996, p. 207.

- ^ For the difference between the terms harakiri (腹切り) and seppuku (切腹), see etymology.

- ^ John Berra (2012). Japan 2. Intellect Books. pp. 151–153. ISBN 978-1-84150-551-0.

- ^ Hoaglund, Linda (1994-05-01). "A Conversation with Kobayashi Masaki". Positions. 2 (2): 393. doi:10.1215/10679847-2-2-382. ISSN 1067-9847.

- ^ Bock, Audie (1985). Japanese film directors. Tokyo: Kodansha International. p. 254. ISBN 0-87011-714-9. OCLC 12250480.

- ^ Bock, p. 256

- ^ Bock, pp. 257-258

- ^ Bock, p. 257

- ^ "Seppuku (Harakiri), Japan, 1962". Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 32, no. 372. London: British Film Institute. 1965. pp. 71–72.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (1964-08-05). "Screen: Samurai With Different Twist: Kobayashi's 'Harakiri' Arrives at Toho". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ Corman, Cid (Spring 1964). "Harakiri". Film Quarterly. 17 (3): 49 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Richie, Donald (2002). A hundred years of Japanese film (1st ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International. pp. 164–165. ISBN 4-7700-2682-X. OCLC 47767410.

- ^ Bock, p. 258

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 23, 2012). "Honor, morality, and ritual suicide". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Harakiri (1962)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Harakiri". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

Sources

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1996). The Japanese Filmography: 1900 through 1994. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0032-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Harakiri at IMDb

- Harakiri at AllMovie

- Harakiri: Kobayashi and History an essay by Joan Mellen at the Criterion Collection

- "切腹 (Seppuku)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-07-16.