Alexander's Ragtime Band

| "Alexander's Ragtime Band" | |

|---|---|

Cover of 1911 sheet music by artist John Frew[1] | |

| Single by Arthur Collins & Byron G. Harlan | |

| Language | English |

| A-side | "Ocean Roll" by Eddie Morton[2] |

| Released | March 18, 1911[3] (sheet music registration) |

| Recorded | May 23, 1911[4] (phonograph recording) |

| Studio | Victor Records |

| Venue | Camden, New Jersey |

| Genre | |

| Length | 3:03[4] |

| Label | Victor 16908[4] |

| Songwriter(s) | Irving Berlin |

"Alexander's Ragtime Band" is a Tin Pan Alley song by American composer Irving Berlin released in 1911 and is often inaccurately[a] cited as his first global hit.[5][6] Although not a traditional ragtime song,[6][7] Berlin's jaunty melody nonetheless "sold a million copies of sheet music in 1911, then another million in 1912, and continued to sell for years afterward. It was the number one song from October 1911 through January 1912."[5] The song might be regarded as a narrative sequel to "Alexander and His Clarinet," which Berlin wrote with Ted Snyder in 1910.[8][9] The earlier song[b] is mostly concerned with a reconciliation between an African-American musician named Alexander Adams and his flame Eliza Johnson, but also highlights Alexander's innovative musical style.[8]

Berlin's "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was introduced to the American public by vaudville comedienne Emma Carus, "one of the great stars of the period."[10] A popular singer in the 1907 Ziegfeld Follies and Broadway features, Carus was a famous contralto of the vaudeville era renowned for her "low bass notes and high lung power."[10] Carus' brassy performance of the song at the American Music Hall in Chicago on April 18, 1911, proved to be well-received,[10] and she toured other metropolises such as Detroit and New York City with acclaimed performances that featured the catchy song.[10]

The song as comically recorded by American singing duo Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan became the number one hit of 1911.[3] Nearly two decades later, jazz singer Bessie Smith recorded a 1927 cover which became one of the hit songs of that year.[5][7] The song's popularity re-surged in the 1930s with the release of a 1934 close harmony cover by the Boswell Sisters,[11] and a 1938 musical film of the same name starring Tyrone Power and Alice Faye.[12] The song was covered by a variety of artists such as Al Jolson,[13] Billy Murray,[14] Louis Armstrong,[7] Bing Crosby,[7] and others.[7] Within fifty years of its release, the song had at least a dozen hit covers.[7]

History

Composition and difficulties

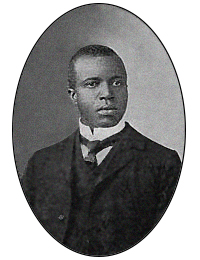

In early March 1911, 23-year-old composer Irving Berlin decided "to try his hand at [writing] an instrumental ragtime number."[15] By this time, the ragtime phenomenon sparked by African-American pianist Scott Joplin had begun to wane,[16] and two decades had passed since the musical genre's heyday in the Gay Nineties.[15]

A tireless workaholic, Berlin purportedly composed the piece while in the noisy offices of a music publishing firm where "five or six pianos and as many vocalists were making bedlam with [other] songs of the day."[17] Purportedly, Berlin composed the lyrics of the song as an ideational sequel to his earlier 1910 composition "Alexander and His Clarinet" which likewise featured a fictional African-American character named Alexander.[8][9] The latter character had been purportedly inspired by Jack Alexander, a cornet-playing African-American bandleader who was friends with Berlin.[18][19][20]

By the next day, Berlin had completed four pages of notes for the copyist-arranger.[21][3] The song later would be "registered in the name of Ted Snyder Co., under E252990 following [its] publication [on] March 18, 1911."[22][19] However, upon showing the composition to others,[9][23] a number of objections were raised: The song "was too long, running beyond the conventional 32 bars; it was too rangy; and besides, it wasn't a real ragtime number anyhow."[23] In fact, the song was a march as opposed to a rag and barely contained "a hint of syncopation."[6] Its sole notability "comprised quotes from a bugle call and Swanee River."[7] Due to such criticisms, many were unimpressed by the tune.[23]

Undaunted by the indifferent response, Berlin submitted the song to Broadway theater producer Jesse L. Lasky who was preparing to debut an extravagant nightclub theater called "the Follies Bergère."[23] However, Lasky was hesitant to the incorporate the pseudo-ragtime number.[23][24] Ultimately, when the show opened on April 27, 1911, Lasky chose only to use its melody whistled by a performer, Otis Harlin.[23][24] Thus the song failed to find an appreciative audience.[23][17]

Fortunately for Berlin, vaudeville singer Emma Carus—famed for her "female baritone"—liked his humorous composition and introduced the song on April 18, 1911, at the American Music Hall in Chicago.[10] She then embarked on a tour of the Midwest in Spring 1911.[10] Consequently, Carus is often cited as largely responsible for showcasing the song to the country and helping contribute to its immense popularity.[5] In gratitude, Berlin credited Carus on the cover of the sheet music.[5] The catchy song became indelibly linked with Carus, although rival performers such as Al Jolson soon co-opted the hit tune.[13]

Berlin also submitted the composition to be used in a special charity performance of the first Friars Frolic by the New York Friars Club.[22] At the Friars Frolic, he performed the song himself on May 28, 1911, at the New Amsterdam Theater.[23] In attendance was fellow composer George M. Cohan who instantly recognized the catchiness of the tune and told Berlin that the song would be an obvious hit.[25]

Meteoric success

"In a few days, 'Alexander's Ragtime Band' will be whistled on the streets and played in the cafés. It is the most meritorious addition to the list of popular songs introduced this season. The vivacious comedienne [Emma Carus] had her audience singing the choruses with her, and those who did not sing, whistled."

— The New York Sun, May 1911[10]

Following its initial release, Berlin's song in 1911 "sold a million copies of sheet music" and "another million in 1912, and continued to sell for years afterward."[5] A subsequent phonograph recording of the song released in 1911 by comedic singers Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan became the best-selling recording in the United States for ten weeks.[3]

Berlin's jaunty composition kick-started a ragtime jubilee—a belated popular celebration of the music that Scott Joplin and other African-American musicians had originated a decade prior.[c] The "jumpy" tune was hailed by Variety magazine as "the musical sensation of the decade."[27]

Over night, Berlin became a cultural luminary.[7] Berlin was subsequently touted as the "King of Ragtime" by an adoring international press,[28][29] an inaccurate title as the song "had little to do with ragtime and everything to do with ragtime audacity, alerting Europe to hot times in the colonies."[28] Baffled by this new title, Berlin publicly insisted that he "didn't originate" ragtime but merely "crystallized it and brought it to people's attention."[30] Historian Mark Sullivan later claimed that, with the auspicious debut of "Alexander's Ragtime Band," Berlin abruptly had "lifted ragtime from the depths of sordid dives to the apotheosis of fashionable vogue."[29]

Cultural sensation

Although not a traditional ragtime song,[6][7] the positive international reception of "Alexander's Ragtime Band" in 1911 led to a musical and dance revival known as "the Ragtime Craze."[31][6] At the time, ragtime music was described as "catching its second wind and ragtime dancing spreading like wildfire."[32] One dancing couple in particular who exemplified this faddish sensation were Vernon and Irene Castle.[32][6] The charismatic, trendsetting duo frequently danced to Berlin's "Alexander's Ragtime Band" and his other "modernist" compositions.[6] The Castles' "modern" dancing pared with Berlin's "modern" songs came to embody the ongoing culture clash between the waning propriety of the Edwardian era and the waxing joviality of the Ragtime revolution on the eve of World War I.[33][34][15] The Daily Express wrote in 1913 that:

"In every London restaurant, park and theater, you hear [Berlin's] strains; Paris dances to it; Vienna has forsaken the waltz; Madrid has flung away her castanets, and Venice has forgotten her barcarolles. Ragtime has swept like a whirlwind over the earth."[31]

Writers such as Edward Jablonski and Ian Whitcomb have emphasized the irony that, in the 1910s, even the upper class of the Russian Empire—a reactionary nation from which Berlin's Jewish forebears had been compelled to flee decades earlier[35]—became enamored with "the ragtime beat with an abandon bordering on mania."[35][36] Specifically, Prince Felix Yusupov, an affluent Russian aristocrat who married the niece of Tsar Nicholas II and later murdered Grigori Rasputin, was described by British socialite Lady Diana Cooper as dancing "around the ballroom like a demented worm" and shouting, "More ragtime!"[35]

Hearing of such improper behavior, cultural commentators diagnosed such manic individuals as "bitten by the ragtime bug"[37] and behaving like "a dog with rabies."[38] They declared that "whether [the ragtime mania] is simply a passing phase of our decadent culture or an infectious disease which has come to stay, like la grippe or leprosy, time alone can show."[38]

Continued popularity

As the years passed, Berlin's "Alexander's Ragtime Band" had many recurrent manifestations as many artists covered it: Billy Murray, in 1912;[14] Bessie Smith, in 1927;[7] Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, in 1930;[39] the Boswell Sisters, in 1934;[11] Louis Armstrong, in 1937;[7] Bing Crosby and Connee Boswell, in 1938;[7] Johnny Mercer, in 1945;[7] Al Jolson, in 1947;[7] Nellie Lutcher, in 1948, and Ray Charles in 1959.[7] Consequently, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" had a dozen hit covers within the half-a-century prior to 1960.[7]

Decades later, reflecting upon the song's unlikely success, Berlin recalled he was utterly astounded by the immediate global acclamation and continued popularity of the innocuous tune.[40] He speculated that its unforeseen success was perhaps due to the lyrics which, although farcical and "silly,"[40] were "fundamentally right" and the piece "started the heels and shoulders of all America and a good section of Europe to rocking."[40]

In 1937, Irving Berlin was approached by 20th Century Fox to write a story treatment for an upcoming film tentatively entitled Alexander's Ragtime Band.[12][41] Berlin agreed to write a story outline for the film which featured twenty-six[42] of Berlin's well-known musical scores.[12][41] During press interviews promoting the film prior to its premiere, Berlin decried articles by the American press which painted ragtime as "the forerunner of jazz."[42] Berlin stated: "Ragtime really shouldn't be called 'the forerunner of jazz' or 'the father of jazz' because, as everyone will tell when they hear some of the old rags, ragtime and jazz are the same."[42]

Released on August 5, 1938, Alexander's Ragtime Band starring Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche was a smash hit and grossed in excess of five million dollars.[12][43][42] However, soon after the film's release, a plagiarism lawsuit was filed by writer Marie Cooper Dieckhaus.[43] After a trial in which evidence was presented, a federal judge ruled in Dieckhaus' favor that Berlin had stolen the plot of her unpublished 1937 manuscript and used many of its elements for the film.[43][41] Dieckhaus had submitted the unpublished manuscript in 1937 to various Hollywood studios, literary agents, and other individuals for their perusal.[43] The judge believed that, after rejecting her manuscript, much of her work was nonetheless appropriated.[43] In 1946, the ruling was reversed on appeal.[41]

Alleged plagiarism

There is some evidence—although inconclusive[44]—that Berlin purloined the melody for "Alexander's Ragtime Band" (in particular, the four notes of "oh, ma honey") from drafts of "Mayflower Rag" and "A Real Slow Drag" by prolific composer Scott Joplin.[44][45][46] Berlin and Joplin were acquaintances in New York, and Berlin had opportunities to hear Joplin's scores prior to publication.[47] At the time, "one of Berlin's functions at the Ted Snyder Music Company was to be on the lookout for publishable music by other composers."[47]

Allegedly, Berlin "heard Joplin's music in one of the offices, played by a staff musician (since Berlin could not read music) or by Joplin himself."[47] According to one account:

"Joplin took some music to Irving Berlin, and Berlin kept it for some time. Joplin went back and Berlin said he couldn't use [the song]. When 'Alexander's Ragtime Band' came out, Joplin said, 'That's my tune.'"[14]

Joplin's widow claimed that, "after Scott had finished writing [Treemonisha], and while he was showing it around, hoping to get it published, [Berlin] stole the theme, and made it into a popular song. The number was quite a hit, too, but that didn't do Scott any good."[14] A relative of John Stillwell Stark, Joplin's music publisher, asserted "the publication of 'Alexander's Ragtime Band' brought Joplin to tears because it was his [own] composition."[14] As writer Edward A. Berlin notes in his work King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era:

"There were rumors heard throughout Tin Pan Alley to the effect that 'Alexander's Ragtime Band' had actually been written by a black man [Scott Joplin], and even a quarter-century later [composer] W.C. Handy told an audience that 'Irving Berlin got all his ideas and most of his music from the late Scott Joplin.' Berlin was aware of the rumors and addressed the issue in a magazine interview in 1916."[44]

Joplin would later die penniless and was buried in an unmarked grave in Queens, New York, on April 1, 1917.[46] For the next half-century, Berlin was incensed by the allegation that a "'black boy' [sic] had written 'Alexander's Ragtime Band'."[48] Responding to his detractors, Berlin stated: "If a negro could write 'Alexander,' why couldn't I? ... If they could produce the negro and he had another hit like 'Alexander' in his system, I would choke it out of him and give him twenty thousands dollars in the bargain."[49][14] In 1914, Berlin further ridiculed the allegation in the lyrics of his composition "He's A Rag Picker."[48] The song features a verse in which a "black character" named Mose claims authorship of "Alexander's Ragtime Band."[48]

Lyrical implications

Although the 1911 sheet music cover drawn by artist John Frew depicts the band's musicians as either white or biracial,[1] Berlin's "Alexander's Ragtime Band"—and his earlier 1910 composition "Alexander and His Clarinet"—employ certain idiomatic expressions ("oh, ma honey," "honey lamb") and vernacular English ("bestest band what am") in the lyrics to indicate to the listener that the characters in the song should be understood to be African-American.[6][48][50]

For example, an often-omitted and risqué[51] second verse identifies the race of Alexander's clarinet player:[50]

Sheet music

-

Page 1

-

Page 2

-

Page 3

-

Page 4

-

Page 5

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Hamm 2012, p. 38: "'Alexander's Ragtime Band' was not Irving Berlin's first commercial hit; a dozen or more of his songs had chalked up substantial sheet music sales before it was published early in 1911. It was [also] not his first song to attract intentional attention."

- ^ Kaplan 2020, p. 41: "In May [1910], Snyder and Berlin published one of their own, 'Alexander and His Clarinet,' a coon song in dialogue between a colored Romeo and his Juliet, with a barely submerged Freudian subtext: 'For lawdy sake [the female character sang], don't dare to go, / My pet, I love you yet, / And then besides, I love your clarinet."

- ^ In a 1913 interview published in the black newspaper New York Age, Scott Joplin asserted that there had been "ragtime music in America ever since the Negro race has been here, but the white people took no notice of it until about twenty years ago [in the 1890s]."[26]

Citations

- ^ a b Hamm 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Ruhlmann 2005, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Ruhlmann 2005, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c d e f Furia & Patterson 2016, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Furia 1992, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Corliss 2001.

- ^ a b c Kaplan 2020, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Giddins 1998, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jablonski 2012, p. 34.

- ^ a b Boswell Sisters 1934.

- ^ a b c d Nugent 1938, p. 7.

- ^ a b Bergreen 1990, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e f Hamm 2012, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Jablonski 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Jablonski 2012.

- ^ a b Hamm 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Streissguth 2011, p. 30.

- ^ a b Fuld 2000, p. 91.

- ^ Freedland 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Jablonski 2012, p. 32.

- ^ a b Hamm 2012, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jablonski 2012, p. 33.

- ^ a b Hamm 2012, p. 51.

- ^ Jablonski 2012, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Joplin interview 1913.

- ^ Bergreen 1990, p. 68.

- ^ a b Giddins 1998, p. 31.

- ^ a b Golden 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Jablonski 2012, p. 36.

- ^ a b Golden 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Golden 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Golden 2007, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Furia 1992, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Whitcomb 1988, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Jablonski 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Golden 2007, p. 53.

- ^ a b Golden 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Lantz 2004.

- ^ a b c Bergreen 1990, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d Dieckhaus 1946.

- ^ a b c d New York Times 1938, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e New York Times 1944, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Berlin 2016, p. 253.

- ^ Hamm 2012, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Ruhling & Levine 2017.

- ^ a b c Hamm 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Hamm 2012, p. 47.

- ^ Berlin 2016, p. 254.

- ^ a b c Herder 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Kaplan 2020, p. 41.

Works cited

- "Alexander's Ragtime Band (2011) by Collins and Harlan". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Berlin, Edward A. (2016) [1994]. King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974032-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bergreen, Laurence (1990). As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-5252-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corliss, Richard (December 24, 2001). "That Old Christmas Feeling: Irving America". Time Magazine. New York. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freedland, Michael (1988). A Salute to Irving Berlin. Singapore: Landmark Books. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55736-084-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fuld, James J. (2000). The Book of World-famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Fifth ed.). New York: Dover Publications. p. 91. ISBN 0-486-41475-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Furia, Philip; Patterson, Laurie J. (2016). The American Song Book: The Tin Pan Alley Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939188-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Furia, Philip (1992). The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America's Great Lyricists. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802288-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Giddins, Gary (1998). Visions of Jazz: The First Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513241-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Golden, Eve (2007). Vernon and Irene Castle's Ragtime Revolution. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 41, 54, 56. ISBN 978-0-8131-2459-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamm, Charles (April 19, 2012). "Excerpt from Alexander and His Band". In Sears, Benjamin (ed.). The Irving Berlin Reader. Readers on American Musicians. New York: Oxford University Press (USA). pp. 38–52. ISBN 978-0-19-538374-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Herder, Ronald, ed. (1998). "Alexander's Ragtime Band". 500 Best-Loved Song Lyrics. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29725-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jablonski, Edward (April 19, 2012). "'Alexander' and Irving". In Sears, Benjamin (ed.). The Irving Berlin Reader. Readers on American Musicians. New York: Oxford University Press (USA). pp. 29–38. ISBN 978-0-19-538374-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaplan, James (January 3, 2020). Irving Berlin: New York Genius. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-300-18048-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lantz, Walter (2004). "The Walter Lantz Cartune Encyclopedia: 1930". The Walter Lantz Cartune Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nugent, Frank S. (August 6, 1938). "The Roxy Plays Host to 'Alexander's Ragtime Band,' a Twentieth Century Tribute to Irving Berlin". The New York Times. New York. p. 7. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Plagiarism Suit Upheld: Federal Court Rules on the Film 'Alexander's Ragtime Band'". The New York Times. March 5, 1944. p. 37. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Ruhling, Nancy A.; Levine, Alexandra S. (May 23, 2017). "Remembering Scott Joplin". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ruhlmann, William (2005) [2004]. "The 1910s". Breaking Records: 100 Years of Hits. New York and London: Taylor & Francis Books. pp. 23–24. ISBN 0-415-94305-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Streissguth, Tom (2011). Say It with Music: A Story about Irving Berlin. Minneapolis: Millbrook Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-87614-810-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "That Ragtime Jubilee". The New York Times. July 31, 1938. p. 126. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "Theatrical Comment: Use of Vulgar Words a Detriment to Ragtime". New York Age. April 3, 1913. p. 6.

- The Boswell Sisters (May 23, 1934). Alexander's Ragtime Band by the Boswell Sisters (78-rpm record). Brunswick Records. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- "Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corp. v. Dieckhaus". United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. March 25, 1946. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via CaseText.com.

- Whitcomb, Ian (1988) [1987]. Irving Berlin and Ragtime America. Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-7126-1664-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)