Hartford City Glass Company

| |

| Company type | Corporation |

|---|---|

| Industry | Glass manufacturing |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Founder | Richard Heagany |

| Defunct | 1899 (facility continued to operate until 1929) |

| Fate | Purchased |

| Successor | Plant No. 3 of American Window Glass Company |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Richard Heagany, J. R. Johnston |

| Products | window glass, chipped glass |

Number of employees | 600(1898) |

Hartford City Glass Company was among the top three window glass manufacturers in the United States between 1890 and 1899, and continued to be one of the nation's largest after its acquisition. It was also the country's largest manufacturer of chipped glass, with capacity double that of its nearest competitor. The company's works was the first of eight glass plants that existed in Hartford City, Indiana during the Indiana Gas Boom. It became the city's largest manufacturer and employer, peaking with 600 employees.

Many of the skilled workers employed at the Hartford City Glass Company were from Belgium, at the time the world’s leading manufacturer of window glass. The Belgian workers and their families accounted for over one-third of Hartford City's population during the 1890s, and lived on the city's south side. Because of the importance of the French-speaking Belgians, one of the local newspapers featured articles in French.

In 1899, Hartford City Glass was acquired by the American Window Glass Company, which controlled 85 percent of the American window glass manufacturing capacity. During the next decade, the company began replacing its skilled and well–paid Belgian glass blowers with machines and less-skilled machine operators. The company used the Hartford City plant to test and refine the new technology. Most of the Belgian glass workers left town.

During the 1920s, competitors developed new window glass production processes that eclipsed the American Window Glass technology, and the company lost its advantage. By the time the Great Depression struck, the Hartford City plant had closed.

Manufacturers drawn to Indiana

During the late 1880s, the discovery of natural gas in Eaton, Indiana started an economic boom period in East Central Indiana.[1][2] Manufacturers were lured to the region to take advantage of the low cost fuel. Blackford County, a small rural county located close to Eaton, had only 181 people working in manufacturing in 1880. By 1901, the county had over 1,100 people employed at manufacturing plants in small communities such as Hartford City, Indiana.[3] Between 1880 and 1900, populations doubled in area counties such as Blackford, Delaware, and Grant.[4] The region became Indiana’s major manufacturing center.[5]

Hartford City

Like many Indiana communities during the gas boom, Hartford City’s leaders sought to take advantage of their newfound energy resource. The Hartford City Land Company was formed in 1891 as part of the effort to attract manufacturers. The company offered "free sites, free gas, excellent switching facilities, and reasonable cash subsidies" as enticements for manufacturers to locate in the boom town.[6] Manufacturers that used high quantities of energy were especially attracted to no-cost or low-cost natural gas sites, and glassmaking was one of those energy-consuming industries.[7]

Hartford City's success in attracting manufacturers can be indirectly measured by its population growth. The city's population was 2,287 in 1890, but grew to 5,912 by 1900.[8] In 1890, the city convinced glassmaker Richard Heagany to relocate from Kokomo, Indiana. An additional glass maker, Sneath Glass Company, relocated from Tiffin, Ohio, in 1894. During 1901, Indiana state inspectors visited 15 manufacturing facilities in Hartford City. These manufacturers employed 1,077 people, and the American Window Glass plant (the former Hartford City Glass Company) plus the Sneath Glass works accounted for over half of the manufacturing employees. By 1902, Hartford City was the home of 8 glass factories.[Note 1]

Organization and management

In 1878, glassmaker Richard Heagany organized a window glass plant in New York and was the factory's superintendent. That plant became the largest window glass plant in the state.[13] In 1886, he moved to Kokomo, Indiana, and opened the first window glass plant in the region to use natural gas as a fuel source. Heagany's Kokomo plant lasted three years before it was destroyed by fire. Instead of rebuilding in Kokomo, he moved to Hartford City and organized the Hartford City Glass Company. The company was organized in 1890 with the financial assistance of several capitalists. Production began in early 1891 after the plant was constructed. Heagany was the plant manager until his retirement in 1899.[13]

Capitalists

One of the principal stockholders of the new company was multi-millionaire A. M. Barber.[14] Barber was involved in grain and banking in Akron, Ohio.[15] Another important investor from Akron was Colonel Arthur Latham Conger, who was the company's first president.[16] Conger was a Civil War veteran who invested in companies in Ohio and Indiana (including in Kokomo).[17] He was also elected president of the Hartford City Land Company in 1893.[18] Hartford City's Sydney W. Cantwell was secretary of the Hartford City Glass Company during its early years. He was also president of the state organization of window glass manufacturers.[19] Cantwell was an attorney involved with the Blackford County Bank, Akron Oil Company, and Hartford City Land Company.[20] Another Hartford City investor, Henry "H. B." Smith, was president of Hartford City's Citizen's Bank.[21]

Management change

Top management changed during 1895 after the company's annual shareholders' meeting. Colonel A. L. Conger, who had been president since the company's beginning, lost his position to another colonel from Akron, George T. Perkins. Conger had fallen into disfavor with many of the local citizens.[22] He immediately expressed his unhappiness with the election by selling his company stock and leaving town. Conger's stock was purchased by Kokomo banker John A. Jay.[23] Officers of Hartford City Glass in 1896 were George T. Perkins, President; John A. Jay, Vice President; H.B. Smith, Treasurer; Richard Heagany, General Manager; and John Rodgers Johnston, Secretary.[24]

Colonel George Tod Perkins was a Civil War veteran and president of the B. F. Goodrich Company. He was also involved in banking and had been president of the Bank of Akron.[25] John R. Johnston began working at the Hartford City plant in 1890 as a bookkeeper. He was elected secretary after 4 years. Johnston lived in Hartford City and helped Heagany run the business. Heagany submitted his resignation at the August 1899 board meeting, retiring after 42 years in the glass business. Johnston became plant manager at that time.[26] Johnston resigned a short time later, effective April 1900. He formed Hartford City's Johnston Glass Company in September of the same year.[27][28]

Workforce

During its peak years, Hartford City Glass Company employed 500 to 600 people. In 1894, it employed 100 glass blowers as part of a total workforce of 540 people. The wages for that workforce were said to be equivalent to "about 1500 men in any other industry."[29] Not only was the glass works the largest industry in the county, it was thought to be the second-largest plant of any industry located in the Indiana Gas Belt.[29] To help meet the housing needs for the factory's many employees, 184 houses were built nearby.[24] In 1896, 443 workers at the plant lived in Hartford City, especially on the south side. Assuming each local worker had a family of five, over one-third of the city's population (2,235 of "an estimated 6,000") was financially dependent upon Hartford City Glass.[24]

Glassmakers

The window glass manufacturing process used by Hartford City Glass was known as the Cylinder Method.[30] The process was labor-intensive, and required the services of a glass blower and glass cutter—who were both highly skilled and well paid. The glass blower led a small production crew that included skilled and unskilled workers. At older plants, the glass blower's workstation was adjacent to a ceramic pot located inside the furnace. Each pot contained molten glass created by melting a batch of ingredients that included sand, soda, and lime.[31] At newer plants such as the Hartford City works, tanks were used instead of pots. The tanks were essentially huge brick pots with multiple workstations. A tank furnace is more efficient than a pot furnace, but more costly to build.[32]

In the first step of the glass-making process, molten glass was extracted from the pot or tank. The glass blower and his helper used a blowpipe, which was typically 4 feet (1.2 m) to 5 feet (1.5 m) long, to create a bubble of molten glass. The glass blower manipulated the bubble into a cylinder, and removed it from the pot or tank. The cylinders were 12 inches (30.5 cm) to 16 inches (40.6 cm) in diameter, and 4 feet (1.2 m) or 5 feet (1.5 m) long.[30]

Next, the glass–cutter cut the cylinder, and the glass was flattened. It was necessary to gradually cool the glass, a process known as annealing, to prevent it from breaking. A lehr or annealing oven was used to anneal the product. A typical 20th-century lehr was a large conveyor inside a long oven. The newly made glass gradually moved from the hot end of the lehr to its opposite end, which was at room temperature. The glass would then be cut into the desired window glass size, placed in a box, and moved to inventory.[33] It is not known if (or when) the lehrs at the Hartford City plant had conveyors.[Note 2]

The Belgians

During the late 19th century, glass blowers were difficult to find. Belgium was the largest exporter of window glass to the United States, and plant manager Heagany previously used the skills of glass blowers from that country in his Kokomo glass works.[13] In Hartford City, Heagany again relied upon Belgian workers for the skilled positions in his glass works.[35]

The city's influx of French-speaking Belgians affected the town. The south side (south of Lick Creek) became known as Belgium Town.[36] Most Belgians were Catholic, and they built the city's Catholic church near their homes on the city's south side.[37] The church's Father Dhe was a native of France and was also involved with glass making.[38] During the early 1900s, the local Blackford County Gazette claimed to be the "only newspaper in State that prints French and circulates among the window glass and iron workers, the highest paid skilled mechanics in the world."[39]

The Belgian workforce also affected the city's north side. Hartford City's Presbyterian Church, which is now part of the National Register of Historical Places, was built one block north of the courthouse in 1894—and features large stained glass windows imported from Belgium.[40] For over 50 years, the bigger of two huge windows was considered the largest single-frame window in the state of Indiana.[41] These stained-glass windows, plus at least four smaller ones, were installed by the local (and mostly Catholic) Belgian glass workers.[40]

Infrastructure

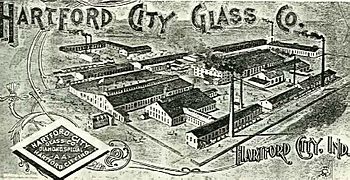

Construction of Hartford City's new glass works was completed in early January 1891, and production started shortly thereafter.[42] The glass works was located on Hartford City's south side, and originally occupied 12 acres (4.9 ha).[43] Natural gas was the plant's original fuel source for both the furnace used to make the glass and the ovens used to gradually cool it.[43]

In the United States, two systems were used during the 1890s to create molten glass. The older system used a pot furnace, where ceramic pots were heated inside the furnace to melt the batch of ingredients needed to make the molten glass. The newer system used a large brick tank that could be operated continuously or by the batch.[44] The Hartford City plant used the tank system, and it was originally the "largest tank window glass factory in the world".[45] The tank had a capacity equivalent to 30 pots,[46] giving the Hartford City plant more than double the capacity of some of the window glass plants built a few years earlier in Ohio.[Note 3]

With its size, newest technology, and newly built facilities, the plant was "said to be the largest and best arranged window glass works in the world."[42] During its existence, the plant was always one of the largest window glass works in the United States.[Note 4]

Initial production at the Hartford City plant continued until June, when the works was shut down to decrease inventories.[51] Summer shutdowns were normal in the glass industry at that time. The heat from the furnaces combined with summer weather made extremely uncomfortable working conditions, justifying the summer months as the best time to shut down for maintenance (or for manipulation of inventories). In the case of the first year's shutdown for the Hartford City Glass works, production was restarted in October.[52]

Expansion

In 1892, management decided to expand the factory's capacity by adding a second tank. The new tank would add approximately 50 pots of capacity.[53] In early April, construction of the facilities for the new tank began. "Modern and improved methods in all departments of the works" were used, improving the efficiency in manufacturing and shipping.[54] The new buildings were made fire-resistant by using stone, brick, and iron for construction materials. They were also well ventilated, which made the work environment more comfortable for the glass workers.[54] The expansion increased total capacity to about 90 pots.[Note 5] This made the works the second-largest glass factory in the United States. Expenditures necessary to finance the expansion were $100,000 (over $2.5 million in 2012 dollars).[56]

During 1893, the company considered adding a third tank, which would add another 60 pots of capacity. The expansion cost estimate was $150,000 (over $3.8 million in 2012 dollars), and was said to "give employment to 350 men."[57] Two major concerns voiced by management to community leaders were adequate fire protection and housing for the workers.[58] Community leaders did not respond soon enough, and the expansion was postponed.[59] However, it is no coincidence that Hartford City's waterworks began operations in 1894, and the plant was built on the city's south side.[60] The city also acquired a chemical fire engine from the Chicago Fire Extinguisher Company, which was delivered in February 1894.[61]

Although the third tank was not added in 1893, a new ware room was built. The room was 60 feet (18.3 m) long by 120 feet (36.6 m) wide, and could hold 20,000 boxes. The roof and walls were covered in iron.[62] By September (without the capacity expansion), the plant had a payroll of $45,000 (over $1.1 million in 2012 dollars) per month, and employed 500 glass workers.[63]

In 1896, the plant employed 550 people, and produced about 2 million square feet of window glass per month.[43] In addition to window glass, the company was the nation’s largest producer of chipped glass, with capacity double that of the second-largest manufacturer. Chipped glass was a popular ornamental glass used for interiors of office buildings and with furniture.[64] At that time, the plant was the second-largest window glass producer in the country, although it became the third-largest later in the year. Its grounds had grown to cover 25 acres (10.1 ha), and included a railroad spur off of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The grounds contained two melting rooms, two warehouses, a blacksmith shop, and a machine shop. The tank in one of the melting rooms was 18 feet (5.5 m) long, 18 feet (5.5 m) wide, and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep. One tank required 4 flattening ovens and a cutting room.[43]

Plans for the addition of another tank began again in late 1896. A third tank would make the Hartford City plant the largest in the country.[65] As part of the conditions for expansion, the plant owners requested housing for its potential new workers. Although the houses were built, the company was not satisfied, as the expansion was never consummated.[Note 6] Without the third tank, the workforce still grew to 600 by 1898.[11]

Acquisition

In 1898, a group of men led by James A. Chambers organized a glass trust called American Window Glass Company. The company was formed from the American Glass Company, but did not incorporate until 1899. The trust planned to acquire 70 glass plants, "some of which it will close to bring the production down to the demand."[68] The prices offered for the glass plants were very generous. Owners of the glass plants could sell their plant for either cash or a combination of cash and stock in the new company. Many owners chose to receive stock.[69]

The trust was incorporated effective August 2, 1899. James A. Chambers continued as president, and Hartford City’s H.B. Smith was one of the directors of the newly incorporated company.[70] Initial acquisitions included over 20 major window glass plants, including Hartford City Glass Company. Most of the original acquisitions were from Indiana and Pennsylvania. Those glass plants were important enough to enable American Window Glass to control 85 percent of the window glass production in the United States.[70]

Many of the Indiana glass works acquired by the trust were from the East Central Indiana Gas Belt. Among those plants were the Hartford City Glass Company; and the nearby Muncie plants of Maring, Hart, and Company and C. H. Over. Other plants were located in Anderson, Dunkirk, and Fairmount, Indiana.[70] The Hartford City Glass Company became known as Plant Number 3 of the American Window Glass Company.[71] J. R. Johnston, already manager for Hartford City Glass Company, was named manager of the American Window Glass version of the same plant in December.[72] A second window glass factory from Hartford City, Jones Glass Company, was also acquired—and became plant No. 32.[12] Eventually, the company acquired 41 glass factories.[73]

American Window Glass

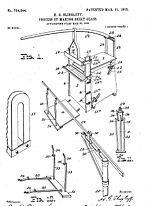

After the acquisition, the Hartford City Glass works became known as plant number 3 of the American Window Glass Company. The plant employed 450 people in 1901.[3] As natural gas supplies in Indiana became depleted, many manufacturers moved or did not survive.[74] The major plants of the American Window Glass successfully changed energy sources from natural gas to gas made from coal.[75] The company also had a technological advantage. Instead of using a glass blower, American Window Glass plants extracted molten glass with a machine. The machine, which was not immediately utilized at all American Window Glass plants, was known as the Lubbers blowing machine. Refinements to the machine and glass-making process were made at the Hartford City works by plant manager Harry G. Slingluff. Production records for the entire company were set at the Hartford City plant in 1905 and 1907—using the Lubbers machines.[71][76]

Lubbers machine

The glass blowing machine used by American Window Glass factories was created by Pittsburgh resident John H. Lubbers, and he continued to contribute improvements to the machine over the next decade.[77] By using the Lubbers machine, human glass blowers were replaced with a machine operator paid 30 percent of the glass blower wage. The machine was also five times more productive than the human blowers. It could make windows four times as large because a larger cylinder was extracted from the tank of molten glass.[71][78] Thus, the highest–paid skilled workers in the United States were considered obsolete. In the case of Hartford City, machines replaced most of the human glass blowers by 1908.[79]

Consolidation

During the spring of 1900, rumors circulated that American Window Glass planned to move production from smaller plants in nearby Dunkirk and Redkey (factories 17, 30, 34, and 41) to the large southside Hartford City plant. If the Hartford City plant would have its capacity expanded equal to the capacity of the plants to be consolidated, then Hartford City would have "become the greatest window glass town in the world."[80] The plant would have employed nearly 1000 people, equaling the largest window glass plant in the world in capacity. That plant in combination with Hartford City's two other window glass factories, not even considering the flint glass plants or bottle plants, would make the city's window glass capacity the highest in the world.[80] The rumor had some truth—smaller plants were eventually closed. However, Hartford City's large southside plant was not expanded.

In 1905 American Window Glass sold some of its smaller plants, including Hartford City's plant number 32.[81] Plant number 3 still continued operations. It employed 500 people in 1910. Before the start of World War I, American Window Glass Company was still the dominant window glass manufacturer, accounting for over half of the nation's window glass manufacturing capacity.[78] In 1913, the company continued to close many of its smaller plants, while the large plants were equipped with the glass blowing machines. Plant number 3 was the third largest window glass factory in the United States, and the largest west of Pennsylvania.[78] The Belgian portion of Hartford City's glassmaking workforce was dramatically reduced because of two factors: the glass-blowing machine replaced human glass blowers; and Belgians had difficulty returning from summer vacations in their European homeland after the start of World War I.[82]

American Window Glass made record profits in 1920. All of the company's small plants had been sold or closed by that time. The glass-blowing machines were still being used to extract molten glass. The company was described as having "six large and well-equipped plants located near the Pittsburgh district, and one large plant at Hartford City, Ind."[83]

Decline

During the beginning of the 20th century, competitors of the American Window Glass trust used a different approach to gain a technological advantage. The machines used by American Window Glass replaced glass blowers, but still used the same blowing and cutting process used in the 1880s—although the company was constantly working to make the process more efficient. Competitors such as American inventor Irving W. Colburn began working on a machine that produced window glass using a different process. Colburn patented his work during the first decade of the 20th century. Although he filed for bankruptcy in 1912, his patents were purchased by Edward Drummond Libbey and Michael J. Owens—who hired Colburn to continue work on the machine.[84] Owens was the creator of the Owens Bottling Machine that revolutionized the glass bottle industry.[85][86] Working with Colburn, Owens improved the window glass machine enough that it began being used for production in 1921. By 1926, Libbey-Owens had gained a window glass market share of 29 percent, while American Window Glass's share was 59 percent. During the 1920s, Pittsburgh Plate Glass also developed a new process for making window glass, creating even more competition in the window glass industry.[84][Note 7]

Because of the improved technology and processes utilized by competitors, many of the American Window Glass patents, and much of its machinery, became obsolete. By the late 1920s, American Window Glass was forced to begin re-equipping its plants with new machinery. The company underwent a financial reorganization in 1929. Dividends on its preferred stock were lowered. Although a few plants were re-equipped, the Hartford City plant was not.[87] Hartford City's natural gas supply was depleted, and the type of sand used to produce glass was in better supply near other American Window Glass plants in Pennsylvania. Thus, American Window Glass Company plant number 3, the former Hartford City Glass Company, was closed in 1929.[30]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ A 1902 Hartford City directory lists 7 glass factories in Hartford City: American Window Glass Company factory number 3, American Window Glass Company factory number 32, Blackford Glass Company, Clelland Glass Company, Diamond Flint Glass Company, Johnston Glass Company, Hartford City Flint Glass Company, and Sneath Glass Company.[9] An eighth plant, the Sans-Pariel Bottle Company, is listed in a 1901 state inspection report.[3] The count of eight factories excludes predecessor companies. The Hurrle Glass Company factory, also listed in the 1901 report, became the Clelland Glass Company.[10] Hartford City Glass Company and Jones Glass Company, both listed in a state inspection report for 1898,[11] became American Window Glass Company factories 3 and 32, respectively.[12]

- ^ For more detail on 1880s glassmaking, see Appendix A in Jack Paquette's Blowpipes book. Paquette, a former Vice President of Owens-Illinois Glass Company, has written at least 3 glass–related books.[34] Window glassmaking at the Hartford City Glass Company plant is discussed, by a former glassworker whose father worked at the Hartford City plant, in a book produced by the Blackford County Historical Society.[30]

- ^ The first window glass plant built in Fostoria, Ohio, (Mambourg Glass Company built in 1887) had a capacity of 13 pots.[47] In Toledo, Ohio, the Toledo Window Glass Company plant was built with a 10 pot capacity in 1888.[48]

- ^ When constructed, the Hartford City Glass Company plant was considered the largest window glass works in the world.[42] For many years, it was one of the three largest window glass plants in the United States—competing with two plants in Pennsylvania. In congressional hearings, the plant was listed as third-largest in the United States (behind the two Pennsylvania plants) in 1898.[49] The same hearings show the Hartford City plant as largest in 1913.[50]

- ^ Capacity "expansion" was difficult to measure precisely. The pot-equivalency of a tank varied, depending on the tank size and way the tank was equipped.[55]

- ^ Testimony before the United States House Committee on Ways and Means in 1913 listed the Hartford City Glass Company as having two tanks in 1898—not three.[66] In 1913, when the plant was owned by American Window Glass Company, it was still described as having two tanks: a large tank "equipped with 10 machines" and a "smaller tank, with a six-machine equipment".[67]

- ^ In Europe, Belgian Emil Fourcault developed his own mechanized method (Fourcault process) to produce window glass. His process was adopted during the 1930s by a group of companies in the United States called Furco Glass. Market share for American Window Glass fell to 20 percent in the United States. The remainder of the market was dominated by three other manufacturers: Libbey-Owens with 30 percent, Pittsburgh Plate Glass with 25 percent, and Furco with 25 percent.[84]

References

- ^ "Indiana's Natural Gas Boom". The American Oil & Gas Historical Society. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 10

- ^ a b c Indiana Department of Inspection 1902, p. 57

- ^ Forstall 1996, pp. 49–53

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 7

- ^ Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) 1896, p. 4

- ^ Hamilton, Abraham & Lankford 2005, p. 13 section 8

- ^ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 16

- ^ Dale 1902, pp. 121–122

- ^ "Company is Organized To Operate the Late Hurrle Glass Factory". Hartford City Telegram. 1895-01-04. p. 1.

- ^ a b Indiana Department of Factory Inspection 1899, p. 44

- ^ a b "Injunction Suits". Hartford City Telegram. 1899-09-27. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Factory Owner of Natural Gas Days Here Dies". Kokomo Daily Tribune. 1925-09-10. p. 1.

- ^ Unlisted (Glass & Pottery World) 1896, p. 10 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFUnlisted_(Glass_&_Pottery_World)1896 (help)

- ^ Graham & Perrin (editor) 1881, p. 684

- ^ Unlisted (Paint, Oil and Drug Review) 1899, p. 13

- ^ Lane 1892, p. 470

- ^ "Indiana State News". Parker News. 1893-09-08. p. 7.

- ^ "Within Our Borders - Will Make No Glass". Goshen Daily News. 1891-09-01. p. 3.

- ^ Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) 1896, p. 30

- ^ Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) 1896, p. 15

- ^ "Dont Bet on the Colonel". Hartford City Telegram. 1894-12-12. p. 1.

- ^ "Col. Conger Beaten". Fort Wayne Weekly Gazette. 1895-09-05. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) 1896, p. 18

- ^ Lane 1892, p. 157

- ^ "Annual Meetings. Manufacturers Directors of the Hartford City Glass Company and Hartford City Land Company Meet". Hartford City Telegram. 1899-08-30. p. 1.

- ^ Fleming & American Historical Society 1922, p. 39

- ^ Castelo et al. 2012, p. 35

- ^ a b "A Big Industry". Hartford City Telegram. 1894-12-05. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Castelo et al. 2012, pp. 16–17

- ^ United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) 1917, p. 55

- ^ United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) 1917, p. 61

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 30

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 469–475

- ^ Clamme & Castelo 2011, p. 11

- ^ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, pp. 48–49

- ^ Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 68

- ^ Clamme & Castelo 2011, p. 23

- ^ Blackford County Gazette (advertisement) 1903, p. 269

- ^ a b Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) 1986, p. 67

- ^ Amstutz & Historical Committee 1943, p. 7

- ^ a b c "(Untitled column on far left near bottom of page)". Rochester Tribune. 1891-01-02. p. 1.

The Hartford City glass works have just been completed and are said to be the largest and best arranged window glass works in the world. The weekly pay roll will amount to over $3,000.

- ^ a b c d Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) 1896, p. 16

- ^ United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) 1917, p. 41

- ^ "In the Gas Fields.". Oskaloosa Daily Herald. 1891-04-27. p. 2.

- ^ "(untitled third column from left)". Hartford City Telegram. 1893-03-02. p. 1.

- ^ Paquette 2002, p. 176

- ^ Paquette 2002, pp. 333–334

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Ways and Means 1913, pp. 410–411

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Ways and Means 1913, pp. 412–413

- ^ "State News - Glass Works Shut Down". Goshen Daily News. 1891-06-03. p. 5.

- ^ "Over the State". Logansport Journal. 1891-10-07. p. 3.

The Hartford City glass works have resumed operations.

- ^ "Indiana State News". Spencer Democrat. 1892-04-07. p. 6.

- ^ a b "WINDOW GLASS NOTES". Hartford City Telegram. 1892-04-07. p. 1.

- ^ Merriam et al. 1901, p. 390

- ^ "Glass Works for Hartford City". Connersville Daily Examiner. 1892-03-31. p. 1.

- ^ "State News Summary". Shoals Martin County Tribune. 1893-03-24. p. 2.

- ^ "Meeting of the Glass Company". Hartford City Telegram. 1893-04-20. p. 1.

- ^ "(untitled third column from right)". Hartford City Telegram. 1893-06-01. p. 1.

- ^ Indiana State Board of Health 1907, p. 250

- ^ Castelo et al. 2012, p. 23

- ^ "(untitled third column from left)". Hartford City Telegram. 1893-04-06. p. 1.

- ^ "From Hoosierdom - Glass Works to Start". Logansport Reporter. 1893-09-20. p. 1.

- ^ Unlisted (Glass & Pottery World) 1896, p. 23 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFUnlisted_(Glass_&_Pottery_World)1896 (help)

- ^ "Indiana News - Enlarging a Glass Plant". Connersville Daily Examiner. 1896-12-28. p. 1.

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Ways and Means 1913, p. 406

- ^ Unlisted (National Glass Budget) 1913, p. 7

- ^ "The Big Trust. The New Window Glass Combine Certain". Hartford City Telegram. 1899-05-17. p. 1.

- ^ "The Glass Trust. Manufacturers Believe It Is a Sure Go". Hartford City Telegram. 1899-07-12. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Wallace 1901, p. 315

- ^ a b c Unlisted (Paint, Oil and Drug Review) 1907, p. 4

- ^ "(untitled second column from right, near bottom of page)". Hartford City Telegram. 1899-12-13. p. 1.

- ^ Hawkins 2009, p. 23

- ^ Glass & Kohrman 2005, p. 91

- ^ "American Window Glass is to Continue the Use of Coal Gas". Hartford City Telegram. 1895-09-27. p. 1.

- ^ "Indiana Company Has New Glass Making Record". Fort Wayne Journal Gazette. 1905-04-09. p. 18.

- ^ Unlisted (National Glass Budget) 1917, p. 1

- ^ a b c Hamor 1913, p. 81

- ^ "Human Blowers Thing of the Past – Machines Replacing Skilled Trades and Obsolete Methods of Manufacture of Window Glass". Daily Times Gazette (Hartford City, Indiana). 1908-04-13. p. 1.

- ^ a b "We'll Lead the World". Portland Semi Weekly Sun. 1900-05-22. p. 1.

- ^ "Offers Old Plants for Sale". Logansport Reporter. 1905-06-15. p. 7.

- ^ Fones-Wolf 2007, p. 138

- ^ Windsor 1921, p. 318

- ^ a b c Chandler 1999, pp. 115–116

- ^ Skrabec 2007, p. 124

- ^ "The Fabulous Monster: Owens Bottle Machine". Corning Museum of Glass. Retrieved 2013-02-23.

- ^ "Belle Vernon and Arnold Plant Method of Window Glass Manufacture Success Certain But Business Is Still Dull". Charleroi (PA) Mail. 1930-02-20. p. 1.

Cited works

- Amstutz, Reverend A. Allison; Historical Committee (1943), "The First 100 Years", Centennial Brochure, First Presbyterian Church of Hartford City, Indiana

- Blackford County Gazette (advertisement) (1903). "The Blackford County Gazette (near bottom of page)". National Newspaper Directory and Gazetteer. Containing a Complete Classified Directory of the Newspapers and Periodicals Published in the United States ... Boston and New York: Pettingill & Co. OCLC 40211971.

- Blackford County Historical Society (Ind.) (1986). A History of Blackford County, Indiana : with historical accounts of the county, 1838–1986 [and] histories of families who have lived in the county. Hartford City, Indiana: Blackford County Historical Society. OCLC 15144953.

- Castelo, Sinuard; Clamme, Louise; Dodds, Dealie; Clamme, David; Marshall, Mary Lou; Storms, Ron (2012). Dusty Bits and Pieces. Hartford City, IN: Blackford County Historical Society. p. 127. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chandler, Alfred Dupont (1999). Scale and scope : the dynamics of industrial capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. p. 765. ISBN 9780674789951. OCLC 248361514. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Clamme, Louise; Castelo, Sinuard (2011). Strangers Among Us. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. p. 196. OCLC 754330971.

- Dale, George R. (1902). Directory of Hartford City, Indiana, Together with a Complete Gazetteer of Blackford County Land Owners. Troy, Ohio: George R. Dale. ISBN 978-1-153-46853-4. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Fleming, George Thornton; American Historical Society (1922). History of Pittsburgh and environs. New York and Chicago: The American Historical Society, Inc. p. 349. OCLC 1040253. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Fones-Wolf, Ken (2007). Glass Towns: Industry, Labor and Political Economy in Appalachia, 1890-1930s. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780252073717. OCLC 256490338. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Forstall, Richard L. (editor) (1996). Population of states and counties of the United States: 1790 to 1990 from the twenty-one decennial censuses. United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Population Division. p. 225. ISBN 0-934213-48-8. OCLC 34927951.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Glass, James A.; Kohrman, David (2005). The Gas Boom of East Central Indiana. Image of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7385-3963-8. OCLC 61885891. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Graham, Albert Adams; Perrin (editor), William Henry (1881). History of Summit County, with an outline sketch of Ohio. Chicago: Baskin & Battey. p. 1050. OCLC 8227777. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

A. M. Barber grain Akron.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - Hamilton, Kristi; Abraham, Kent; Lankford, Susan (2005). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Hartford City Courthouse Square District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- Hamor, W. A. (1913). "The Present Status of the Window Glass Industry". The Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. 5 (1). Easton, PA: American Chemical Society: 80–81. doi:10.1021/ie50049a053. OCLC 1606890.

- Hawkins, Jay W. (2009). Glasshouses and Glass Manufacturers of the Pittsburgh Region 1795 – 1910. New York: iUniverse. ISBN 9781440114946. OCLC 429680614. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- Indiana Department of Factory Inspection (1899). "Exhibit A.—Factories Inspected—Continued – Hartford City, Blackford County". Annual Report of the Department of Factory Inspection. 2 (1898). Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Factory Inspection. OCLC 243873835.

- Indiana Department of Inspection (1902). "Annual report of the Department of Inspection of manufacturing and mercantile establishments, laundries, bakeries, quarries, printing offices and public buildings" (1901). Indianapolis: Indiana Department of Inspection. OCLC 13018369.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Indiana State Board of Health (1907). "Annual Report of the State Board of Health of Indiana". 25 (Statistical Year Ending December 31, 1906). Indianapolis: Indiana State Board of Health. OCLC 12626573.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lane, Samuel Alanson (1892). Fifty years and over of Akron and Summit County : embellished by nearly six hundred engravings--portraits of pioneer settlers, prominent citizens, business, official and professional--ancient and modern views, etc.; nine-tenth's of a century of solid local history--pioneer incidents, interesting events--industrial, commercial, financial and educational progress, biographies, etc. Akron, OH: Beacon Job Department. p. 1167. OCLC 20648565. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

A. L. Conger glass Hartford.

- Merriam, William Rush; Hunt, William C.; King, William Alexander; Powers, Le Grand; North, Simon Newton Dexter; United States Census Office (1901). Census reports ... Twelfth census of the United States, taken in the year 1900. Washington: United States Census Office. OCLC 227718. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. p. 559. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Michael Owens and the Glass Industry. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing. p. 320. OCLC 137341537.

- United States Bureau of foreign and domestic commerce (Dept. of Commerce) (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the cost of production of glass in the United States. Washington. p. 430. OCLC 5705310. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - United States Congress House Committee on Ways and Means (1913). Tariff schedule, no. 3-4. Hearings before the committee on Schedule B - earths, earthenware, and glassware, January, 1913. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 81218187. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Unlisted (Glass & Pottery World) (1896). "Chipped and Ground Glass". Glass & Pottery World. IV (2). Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. OCLC 1390202.

- Unlisted (Glass & Pottery World) (1896). "Returned". Glass & Pottery World. IV (8). Chicago: Trade Magazine Association. OCLC 1390202.

- Unlisted (Hartford City Illustrated) (1896). Hartford City illustrated : a publication devoted to the city's best interests and containing half tone engravings of prominent factories, business blocks, residences, and a selection of representative commercial and professional men and women. Daulton & Scott. p. 47. OCLC 11382905. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- Unlisted (National Glass Budget) (1913). "Successful Start at Hartford". National Glass Budget. 29 (28). Chicago: 7. OCLC 750938784.

- Unlisted (National Glass Budget) (1917). "The Window Glass Machine". National Glass Budget. 32 (49). Chicago: 1. OCLC 750938784.

- Unlisted (Paint, Oil and Drug Review) (1899). "(untitled column on left)". Paint, Oil and Drug Review. 27 (15). Chicago: D. Van Ness Publishing Company: 13. OCLC 7711980.

- Unlisted (Paint, Oil and Drug Review) (1907). "Machine Window Glass Production". Paint, Oil and Drug Review. 44 (1). Chicago: D. Van Ness. OCLC 1585526.

- Wallace, Henry E. (1901). "American Window Glass Co". The Manual of Statistics: Stock Exchange Handbook. 23. New York: Charles H. Nicoll. OCLC 1865454.

- Windsor, John T. (January 8, 1921). "Prosperity in Glass Manufacturing Industry". The Magazine of Wall Street. 27. New York: Ticker Publishing Company. OCLC 7863409.

American Window Glass Made High Record Earnings in the Year Ended August Last – Largest Company of the Kind in the World