Ada Lovelace

Ada, Countess of Lovelace | |

|---|---|

Ada, Countess of Lovelace, 1840 | |

| Born | The Hon. Augusta Ada Byron 10 December 1815 London, England |

| Died | 27 November 1852 (aged 36) Marylebone, London, England |

| Resting place | Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall, Nottingham, England |

| Known for | Mathematics Computing |

| Title | Countess of Lovelace |

| Spouse | William King-Noel, 1st Earl of Lovelace |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

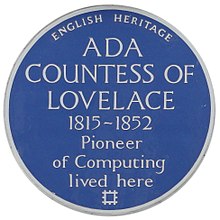

Augusta Ada King-Noel, Countess of Lovelace (née Byron; 10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852) was an English mathematician and writer, chiefly known for her work on Charles Babbage's early mechanical general-purpose computer, the Analytical Engine. Her notes on the engine include what is recognised as the first algorithm intended to be carried out by a machine. As a result, she is often regarded as the first computer programmer.[1][2][3]

Ada Lovelace was the only legitimate child of the poet George, Lord Byron and his wife Anne Isabella Milbanke ("Annabella"), Lady Wentworth.[4] All Byron's other children were born out of wedlock to other women.[5] Byron separated from his wife a month after Ada was born and left England forever four months later, eventually dying of disease in the Greek War of Independence when Ada was eight years old. Her mother remained bitter towards Lord Byron and promoted Ada's interest in mathematics and logic in an effort to prevent her from developing what she saw as the insanity seen in her father, but Ada remained interested in him despite this (and was, upon her eventual death, buried next to him at her request). Often ill, she spent most of her childhood sick. Ada married William King in 1835. King was made Earl of Lovelace in 1838, and she became Countess of Lovelace.

Her educational and social exploits brought her into contact with scientists such as Andrew Crosse, Sir David Brewster, Charles Wheatstone, Michael Faraday and the author Charles Dickens, which she used to further her education. Ada described her approach as "poetical science"[6] and herself as an "Analyst (& Metaphysician)".[7]

When she was a teenager, her mathematical talents led her to an ongoing working relationship and friendship with fellow British mathematician Charles Babbage, also known as 'the father of computers', and in particular, Babbage's work on the Analytical Engine. Lovelace first met him in June 1833, through their mutual friend, and her private tutor, Mary Somerville. Between 1842 and 1843, Ada translated an article by Italian military engineer Luigi Menabrea on the engine, which she supplemented with an elaborate set of notes, simply called Notes. These notes contain what many consider to be the first computer program—that is, an algorithm designed to be carried out by a machine. Lovelace's notes are important in the early history of computers. She also developed a vision of the capability of computers to go beyond mere calculating or number-crunching, while many others, including Babbage himself, focused only on those capabilities.[8] Her mind-set of "poetical science" led her to ask questions about the Analytical Engine (as shown in her notes) examining how individuals and society relate to technology as a collaborative tool.[5]

She died of uterine cancer in 1852 at the age of 36.

Biography

Childhood

Byron expected his baby to be a "glorious boy" and was disappointed when his wife gave birth to a girl.[9] Augusta was named after Byron's half-sister, Augusta Leigh, and was called "Ada" by Byron himself.[10]

On 16 January 1816 Annabella, at Byron's behest, left for her parents' home at Kirkby Mallory taking one-month-old Ada with her.[9] Although English law at the time gave fathers full custody of their children in cases of separation, Byron made no attempt to claim his parental rights[11] but did request that his sister keep him informed of Ada's welfare.[12] On 21 April Byron signed the Deed of Separation, although very reluctantly, and left England for good a few days later.[13] Aside from an acrimonious separation, Annabella continually made allegations about Byron's immoral behaviour throughout her life.[14]

This set of events made Ada famous in Victorian society. Byron did not have a relationship with his daughter, and never saw her again. He died in 1824 when she was eight years old. Her mother was the only significant parental figure in her life.[15] Ada was not shown the family portrait of her father (covered in green shroud) until her twentieth birthday.[16] Her mother became Baroness Wentworth in her own right in 1856.

Annabella did not have a close relationship with the young Ada, and often left her in the care of her own mother Judith, Hon. Lady Milbanke, who doted on her grandchild. However, because of societal attitudes of the time—which favoured the husband in any separation, with the welfare of any child acting as mitigation—Annabella had to present herself as a loving mother to the rest of society. This included writing anxious letters to Lady Milbanke about Ada's welfare, with a cover note saying to retain the letters in case she had to use them to show maternal concern.[17] In one letter to Lady Milbanke, she referred to Ada as "it": "I talk to it for your satisfaction, not my own, and shall be very glad when you have it under your own."[18] In her teenage years, several of her mother's close friends watched Ada for any sign of moral deviation. Ada dubbed these observers the "Furies", and later complained they exaggerated and invented stories about her.[19]

Ada was often ill, beginning in early childhood. At the age of eight, she experienced headaches that obscured her vision.[10] In June 1829, she was paralysed after a bout of measles. She was subjected to continuous bed rest for nearly a year, which may have extended her period of disability. By 1831, she was able to walk with crutches. Despite being ill Ada developed her mathematical and technological skills. At age 12 this future "Lady Fairy", as Charles Babbage affectionately called her, decided she wanted to fly. Ada went about the project methodically, thoughtfully, with imagination and passion. Her first step in February 1828, was to construct wings. She investigated different material and sizes. She considered various materials for the wings: paper, oilsilk, wires and feathers. She examined the anatomy of birds to determine the right proportion between the wings and the body. She decided to write a book Flyology illustrating, with plates, some of her findings. She decided what equipment she would need, for example, a compass, to "cut across the country by the most direct road", so that she could surmount mountains, rivers and valleys. Her final step was to integrate steam with the "art of flying".[5]

In early 1833 Ada had an affair with a tutor and, after being caught, tried to elope with him. The tutor's relatives recognised her and contacted her mother. Annabella and her friends covered the incident up to prevent a public scandal.[20] Ada never met her younger half-sister, Allegra, the daughter of Lord Byron and Claire Clairmont. Allegra died in 1822 at the age of five. Ada did have some contact with Elizabeth Medora Leigh, the daughter of Byron's half-sister Augusta Leigh, who purposely avoided Ada as much as possible when introduced at Court.[21]

Adult years

Lovelace became close friends with her tutor Mary Somerville, who would introduce her to Charles Babbage in 1833. She had a strong respect and affection for Somerville,[22] and the two of them corresponded for many years. Other acquaintances included the scientists Andrew Crosse, Sir David Brewster, Charles Wheatstone, Michael Faraday and the author Charles Dickens. She was presented at Court at the age of seventeen "and became a popular belle of the season" in part because of her "brilliant mind."[23] By 1834 Ada was a regular at Court and started attending various events. She danced often and was able to charm many people, and was described by most people as being dainty, although John Hobhouse, Byron's friend, described her as "a large, coarse-skinned young woman but with something of my friend's features, particularly the mouth".[24] This description followed their meeting on 24 February 1834 in which Ada made it clear to Hobhouse that she did not like him, probably because of the influence of her mother, which led her to dislike all of her father's friends. This first impression was not to last, and they later became friends.[25]

On 8 July 1835 she married William, 8th Baron King,[a] becoming Lady King.[26] Their residence was Ockham Park, a large estate in Surrey, along with another estate on Loch Torridon in Ross-shire, and a home in London. They spent their honeymoon at Worthy Manor in Ashley Combe near Porlock Weir, Somerset. The Manor had been built as a hunting lodge in 1799 and was improved by King in preparation for their honeymoon. It later became their summer retreat and was further improved during this time.

They had three children: Byron (born 12 May 1836); Anne Isabella (called Annabella; born 22 September 1837); and Ralph Gordon (born 2 July 1839). Immediately after the birth of Annabella, Lady King experienced "a tedious and suffering illness, which took months to cure."[25] Ada was a descendant of the extinct Barons Lovelace and in 1838, her husband was made Earl of Lovelace and Viscount Ockham,[27] meaning Ada became the Countess of Lovelace. In 1843–44, Ada's mother assigned William Benjamin Carpenter to teach Ada's children, and to act as a 'moral' instructor for Ada.[28] He quickly fell for her, and encouraged her to express any frustrated affections, claiming that his marriage meant he'd never act in an "unbecoming" manner. When it became clear that Carpenter was trying to start an affair, Ada cut it off.[29]

In 1841 Lovelace and Medora Leigh (the daughter of Lord Byron's half-sister Augusta Leigh) were told by Ada's mother that her father was also Medora's father.[30] On 27 February 1841 Ada wrote to her mother: "I am not in the least astonished. In fact you merely confirm what I have for years and years felt scarcely a doubt about, but should have considered it most improper in me to hint to you that I in any way suspected."[31] She did not blame the incestuous relationship on Byron, but instead blamed Augusta Leigh: "I fear she is more inherently wicked than he ever was."[32] In the 1840s Ada flirted with scandals: firstly from a relaxed relationship with men who were not her husband, which led to rumours of affairs[33]—and secondly, her love of gambling. The gambling led to her forming a syndicate with male friends, and an ambitious attempt in 1851 to create a mathematical model for successful large bets. This went disastrously wrong, leaving her thousands of pounds in debt to the syndicate, forcing her to admit it all to her husband.[34] She had a shadowy relationship with Andrew Crosse's son John from 1844 onwards. John Crosse destroyed most of their correspondence after her death as part of a legal agreement. She bequeathed him the only heirlooms her father had personally left to her.[35] During her final illness, she would panic at the idea of the younger Crosse being kept from visiting her.[36]

Education

Throughout her illnesses, she continued her education.[37] Her mother's obsession with rooting out any of the insanity of which she accused Byron was one of the reasons that Ada was taught mathematics from an early age. She was privately schooled in mathematics and science by William Frend, William King, and Mary Somerville, the noted researcher and scientific author of the 19th century. One of her later tutors was the mathematician and logician Augustus De Morgan. From 1832, when she was seventeen, her mathematical abilities began to emerge,[23] and her interest in mathematics dominated the majority of her adult life. In a letter to Lady Byron, De Morgan suggested that her daughter's skill in mathematics could lead her to become "an original mathematical investigator, perhaps of first-rate eminence".[38]

Lovelace often questioned basic assumptions by integrating poetry and science. While studying differential calculus, she wrote to De Morgan:

I may remark that the curious transformations many formulae can undergo, the unsuspected and to a beginner apparently impossible identity of forms exceedingly dissimilar at first sight, is I think one of the chief difficulties in the early part of mathematical studies. I am often reminded of certain sprites and fairies one reads of, who are at one's elbows in one shape now, and the next minute in a form most dissimilar[39]

Lovelace believed that intuition and imagination were critical to effectively applying mathematical and scientific concepts. She valued metaphysics as much as mathematics, viewing both as tools for exploring "the unseen worlds around us".[40]

Death

Lovelace died at the age of 36 – the same age that her father had died – on 27 November 1852,[41] from uterine cancer probably exacerbated by bloodletting by her physicians.[42] The illness lasted several months, in which time Annabella took command over whom Ada saw, and excluded all of her friends and confidants. Under her mother's influence, she had a religious transformation and was coaxed into repenting of her previous conduct and making Annabella her executor.[43] She lost contact with her husband after she confessed something to him on 30 August which caused him to abandon her bedside. What she told him is unknown.[44] She was buried, at her request, next to her father at the Church of St. Mary Magdalene in Hucknall, Nottinghamshire.

Work

Throughout her life, Lovelace was strongly interested in scientific developments and fads of the day, including phrenology[45] and mesmerism.[46] After her work with Babbage, Lovelace continued to work on other projects. In 1844 she commented to a friend Woronzow Greig about her desire to create a mathematical model for how the brain gives rise to thoughts and nerves to feelings ("a calculus of the nervous system").[47] She never achieved this, however. In part, her interest in the brain came from a long-running pre-occupation, inherited from her mother, about her 'potential' madness. As part of her research into this project, she visited the electrical engineer Andrew Crosse in 1844 to learn how to carry out electrical experiments.[48] In the same year, she wrote a review of a paper by Baron Karl von Reichenbach, Researches on Magnetism, but this was not published and does not appear to have progressed past the first draft.[49] In 1851, the year before her cancer struck, she wrote to her mother mentioning "certain productions" she was working on regarding the relation of maths and music.[50]

Lovelace first met Charles Babbage in June 1833, through their mutual friend Mary Somerville. Later that month Babbage invited Lovelace to see the prototype for his Difference Engine.[51] She became fascinated with the machine and used her relationship with Somerville to visit Babbage as often as she could. Babbage was impressed by Lovelace's intellect and analytic skills. He called her "The Enchantress of Number".[52][note 1] In 1843 he wrote of her:

Forget this world and all its troubles and if possible its multitudinous Charlatans—every thing in short but the Enchantress of Number.[52]

During a nine-month period in 1842–43, Lovelace translated the Italian mathematician Luigi Menabrea's article on Babbage's newest proposed machine, the Analytical Engine. With the article, she appended a set of notes.[53] Explaining the Analytical Engine's function was a difficult task, as even many other scientists did not really grasp the concept and the British establishment was uninterested in it.[54] Lovelace's notes even had to explain how the Analytical Engine differed from the original Difference Engine.[55] Her work was well received at the time; the scientist Michael Faraday described himself as a supporter of her writing.[56]

The notes are around three times longer than the article itself and include (in Section G[57]), in complete detail, a method for calculating a sequence of Bernoulli numbers with the Engine, which could have run correctly[citation needed] had the Analytical Engine been built (only his Difference Engine has been built, completed in London in 2002[58]). Based on this work Lovelace is now widely considered the first computer programmer[1] and her method is recognised as the world's first computer program.[59]

Section G also contains Lovelace's dismissal of artificial intelligence. She wrote that "The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths." This objection has been the subject of much debate and rebuttal, for example by Alan Turing in his paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence".[60]

Lovelace and Babbage had a minor falling out when the papers were published, when he tried to leave his own statement (a criticism of the government's treatment of his Engine) as an unsigned preface—which would imply that she had written that also. When Taylor's Scientific Memoirs ruled that the statement should be signed, Babbage wrote to Lovelace asking her to withdraw the paper. This was the first that she knew he was leaving it unsigned, and she wrote back refusing to withdraw the paper. The historian Benjamin Woolley theorised that, "His actions suggested he had so enthusiastically sought Ada's involvement, and so happily indulged her ... because of her 'celebrated name'."[61] Their friendship recovered, and they continued to correspond. On 12 August 1851, when she was dying of cancer, Lovelace wrote to him asking him to be her executor, though this letter did not give him the necessary legal authority. Part of the terrace at Worthy Manor was known as Philosopher's Walk, as it was there that Lovelace and Babbage were reputed to have walked while discussing mathematical principles.[56]

First computer program

In 1840, Babbage was invited to give a seminar at the University of Turin about his Analytical Engine. Luigi Menabrea, a young Italian engineer, and the future Prime Minister of Italy, wrote up Babbage's lecture in French, and this transcript was subsequently published in the Bibliothèque universelle de Genève in October 1842. Babbage's friend Charles Wheatstone commissioned Ada Lovelace to translate Menabrea's paper into English. She then augmented the paper with notes, which were added to the translation. Ada Lovelace spent the better part of a year doing this, assisted with input from Babbage. These notes, which are more extensive than Menabrea's paper, were then published in Taylor's Scientific Memoirs under the initialism AAL.

In 1953, more than a century after her death, Ada Lovelace's notes on Babbage's Analytical Engine were republished. The engine has now been recognised as an early model for a computer and her notes as a description of a computer and software.[62]

Ada Lovelace's notes were labelled alphabetically from A to G. In note G, she describes an algorithm for the Analytical Engine to compute Bernoulli numbers. It is considered the first published algorithm ever specifically tailored for implementation on a computer, and Ada Lovelace has often been cited as the first computer programmer for this reason.[63][64] The engine was never completed so her program was never tested.[65]

Beyond numbers

In her notes, Lovelace emphasised the difference between the Analytical Engine and previous calculating machines, particularly its ability to be programmed to solve problems of any complexity.[66] She realised the potential of the device extended far beyond mere number crunching. In her notes, she wrote:

[The Analytical Engine] might act upon other things besides number, were objects found whose mutual fundamental relations could be expressed by those of the abstract science of operations, and which should be also susceptible of adaptations to the action of the operating notation and mechanism of the engine...Supposing, for instance, that the fundamental relations of pitched sounds in the science of harmony and of musical composition were susceptible of such expression and adaptations, the engine might compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent.[67][68]

This analysis was an important development from previous ideas about the capabilities of computing devices, and anticipated the implications of modern computing one hundred years before they were realised. Walter Isaacson ascribes Lovelace's insight regarding the application of computing to any process based on logical symbols to an observation about textiles: "When she saw some mechanical looms that used punchcards to direct the weaving of beautiful patterns, it reminded her of how Babbage's engine used punched cards to make calculations."[69] This insight is seen as significant by writers such as Betty Toole and Benjamin Woolley, as well as the programmer John Graham-Cumming, whose project Plan 28 has the aim of constructing the first complete Analytical Engine.[70][71][72]

Controversy over extent of contributions

Though Lovelace is referred to as the first computer programmer, some biographers and historians of computing claim the contrary.

Allan G. Bromley, in the 1990 article Difference and Analytical Engines:

All but one of the programs cited in her notes had been prepared by Babbage from three to seven years earlier. The exception was prepared by Babbage for her, although she did detect a 'bug' in it. Not only is there no evidence that Ada ever prepared a program for the Analytical Engine, but her correspondence with Babbage shows that she did not have the knowledge to do so.[73]

Bruce Collier, who later wrote a biography of Babbage, wrote in his 1970 Harvard University PhD thesis that Lovelace "made a considerable contribution to publicizing the Analytical Engine, but there is no evidence that she advanced the design or theory of it in any way".[74]

Eugene Eric Kim and Betty Alexandra Toole consider it "incorrect" to regard Lovelace as the first computer programmer, as Babbage wrote the initial programs for his Analytical Engine, although the majority were never published.[75] Bromley notes several dozen sample programs prepared by Babbage between 1837 and 1840, all substantially predating Lovelace's notes.[76] Dorothy K. Stein regards Lovelace's notes as "more a reflection of the mathematical uncertainty of the author, the political purposes of the inventor, and, above all, of the social and cultural context in which it was written, than a blueprint for a scientific development".[77]

In popular culture

Lovelace has been portrayed in Romulus Linney's 1977 play Childe Byron,[78] the 1990 steampunk novel The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling,[79] the 1997 film Conceiving Ada,[80] and in John Crowley's 2005 novel Lord Byron's Novel: The Evening Land, where she is featured as an unseen character whose personality is forcefully depicted in her annotations and anti-heroic efforts to archive her father's lost novel.[81]

In Tom Stoppard's 1993 play Arcadia, the precocious teenage genius Thomasina Coverly (a character "apparently based" on Ada Lovelace—the play also involves Lord Byron) comes to understand chaos theory, and theorises the second law of thermodynamics, before either is officially recognised.[82][83] The 2015 play Ada and the Memory Engine by Lauren Gunderson portrays Lovelace and Charles Babbage in unrequited love, and it imagines a post-death meeting between Lovelace and her father.[84][85]

Lovelace and Babbage are the main characters in Sydney Padua's webcomic and graphic novel The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage. The comic features extensive footnotes on the history of Ada Lovelace and many lines of dialogue are drawn from actual correspondence.[86]

Commemoration

The computer language Ada, created on behalf of the United States Department of Defense, was named after Lovelace. The reference manual for the language was approved on 10 December 1980 and the Department of Defense Military Standard for the language, MIL-STD-1815, was given the number of the year of her birth. Since 1998 the British Computer Society has awarded a medal in her name[87] and in 2008 initiated an annual competition for women students of computer science.[88] In the UK the BCSWomen Lovelace Colloquium, the annual conference for women undergraduates is named after Lovelace.[89]

"Ada Lovelace Day" is an annual event celebrated in mid-October[90] whose goal is to "... raise the profile of women in science, technology, engineering and maths," and to "create new role models for girls and women" in these fields.

The Ada Initiative is a non-profit organisation dedicated to increasing the involvement of women in the free culture and open source movements.[91]

The Engineering in Computer Science and Telecommunications College building in Zaragoza University is called the Ada Byron Building.[92] The village computer centre in the village of Porlock, near where Ada Lovelace lived, is named after her. There is a building in the small town of Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire named Ada Lovelace House.[93] One of the tunnel boring machines excavating the tunnels for London's Crossrail project is named Ada in commemoration of Ada Lovelace.[94]

Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology is an "open-access, multi-modal, [open-]peer-reviewed feminist journal concerned with the intersections of gender, new media, and technology" that began in 2012 and is run by the Fembot Collective.[95]

Adafruit Industries is an open-source hardware company named in honour of Lovelace.[96]

Ada College a further-education college in Tottenham Hale, London focused on digital skills, is named after Lovelace.[97]

Titles and styles by which she was known

- 10 December 1815 – 8 July 1835: The Honourable Ada Byron

- 8 July 1835 – 30 June 1838: The Right Honourable The Lady King

- 30 June 1838 – 27 November 1852: The Right Honourable The Countess of Lovelace

Ancestry

| Family of Ada Lovelace | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bicentenary

The bicentenary of Ada Lovelace's birth was celebrated with a number of events, including:[98]

- The Ada Lovelace Bicentenary Lectures on Computability, Israel Institute for Advanced Studies, 20 December 2015 – 31 January 2016.[99][100]

- Ada Lovelace Symposium, University of Oxford, 13–14 October 2015.[101]

Special exhibitions were displayed by the Science Museum in London[102] and the Weston Library[103] (part of the Bodleian Library) in Oxford, England.

Publications

- Menabrea, Luigi Federico; Lovelace, Ada (1843). "Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage... with notes by the translator. Translated by Ada Lovelace". In Richard Taylor (ed.). Scientific Memoirs. Vol. 3. London: Richard and John E. Taylor. pp. 666–731.

See also

- Great Lives (BBC Radio 4) aired on 17 September 2013 was dedicated to the story of Ada Lovelace.[104]

- Code: Debugging the Gender Gap

- Women in computing

Notes

This section appears to contradict itself. (May 2016) |

- ^ Sources disagree on whether William King, her maths tutor, and William King, her later husband, were the same person.

- ^ Some writers give it as "Enchantress of Numbers"

Sources make it clear that William King, her tutor, and William King, her future husband, were not related.[105]

References

- ^ a b Fuegi & Francis 2003, pp. 16–26.

- ^ Phillips, Ana Lena (November–December 2011). "Crowdsourcing Gender Equity: Ada Lovelace Day, and its companion website, aims to raise the profile of women in science and technology". American Scientist. 99 (6): 463.

- ^ "Ada Lovelace honoured by Google doodle". The Guardian. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ Ada Lovelace Biography, biography.com

- ^ a b c Toole, Betty Alexandra (1987), "Poetical Science", The Byron Journal, 15: 55–65, doi:10.3828/bj.1987.6.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Fuegi & Francis 2003, pp. 19, 25.

- ^ a b Turney 1972, p. 35.

- ^ a b Stein 1985, p. 17.

- ^ Stein 1985, p. 16.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Turney 1972, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Turney 1972, p. 138.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 86.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 119.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Turney 1972, p. 155.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 138–40.

- ^ a b Turney 1972, p. 138.

- ^ Turney 1972, pp. 138–39.

- ^ a b Turney 1972, p. 139.

- ^ "Ada Augusta Byron", The Peerage, 31 January 2012.

- ^ "Lovelace, Earl of". Cracroft's Peerage. 2005.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 285–86.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 289–96.

- ^ Turney 1972, p. 159.

- ^ Turney 1972, p. 160.

- ^ Moore 1961, p. 431.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 302.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 340–42.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 336–37.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 361.

- ^ Stein 1985, pp. 28–30.

- ^ Stein 1985, p. 82.

- ^ Toole 1998, p. 99.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 91–100.

- ^ "December 1852 1a * MARYLEBONE – Augusta Ada Lovelace", Register of Deaths, GRO.

- ^ Baum 1986, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 370.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 369.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 198.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 232–33.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 305.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 310–14.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 315–17.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 335.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b Wolfram, Stephen (10 December 2015). "Untangling the Tale of Ada Lovelace".

Then, on Sept. 9, Babbage wrote to Ada, expressing his admiration for her and (famously) describing her as 'Enchantress of Number' and 'my dear and much admired Interpreter'. (Yes, despite what's often quoted, he wrote 'Number' not 'Numbers'.)

- ^ Menabrea 1843.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 265.

- ^ Woolley 1999, p. 267.

- ^ a b Woolley 1999, p. 307.

- ^ "Sketch of The Analytical Engine, with notes upon the Memoir by the Translator". Switzerland: fourmilab.ch. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "The Babbage Engine". Computer History Museum. 2008.

- ^ Gleick, J. (2011) The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, London, Fourth Estate, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Alan Turing (2004). Stuart Shieber (ed.). Computing Machinery and Intelligence. MIT Press. pp. 67–104.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 277–80.

- ^ Hammerman, Robin; Russell, Andrew L., eds. (2015), Ada's Legacy: Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the Digital Age, Morgan & Claypool, doi:10.1145/2809523

- ^ Simonite, Tom (24 March 2009). "Short Sharp Science: Celebrating Ada Lovelace: the 'world's first programmer'". New Scientist. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Parker, Matt (2014). Things to Make and Do in the Fourth Dimension. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 261. ISBN 0374275653.

- ^ Kim & Toole 1999.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 175–82.

- ^ Lovelace, Ada; Menabrea, Luigi (1842). "Sketch of the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage Esq". Scientific Memoirs. Richard Taylor: 694.

- ^ Hooper, Rowan (16 October 2012). "Ada Lovelace: My brain is more than merely mortal". New Scientist. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter. "Walter Isaacson on the women of ENIAC." Fortune magazine. 18 September 2014.

- ^ Toole 1998, pp. 2–3, 14.

- ^ Woolley 1999, pp. 272–77.

- ^ Kent, Leo (17 September 2012). "The 10-year-plan to build Babbage's Analytical Engine". Humans Invent. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Bromley, Allan G. (1990). "Difference and Analytical Engines" (pdf). In Aspray, William (ed.). Computing Before Computers. Ames: Iowa State University Press. pp. 59–98. ISBN 0-8138-0047-1. p. 89.

- ^ Collier, Bruce (1970). The Little Engines That Could've: The Calculating Machines of Charles Babbage (Ph.D.). Harvard University. Retrieved 18 December 2015. chapter 3.

- ^ Kim & Toole 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Bromley, Allan G. (July–September 1982). "Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine, 1838" (pdf). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 4 (3): 197–217. doi:10.1109/mahc.1982.10028. p. 197.

- ^ Stein, Dorothy K. (1984). "Lady Lovelace's Notes: Technical Text and Cultural Context". Victorian Studies. 28 (1): 33–67. p. 34.

- ^ Klein, Alvin (13 May 1984), "Theatre in review: A lusty Byron in Rockland", New York Times

- ^ Plant, Sadie (1995), "The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics", in Featherstone, Mike; Burrows, Roger (eds.), Cyberspace/Cyberbodies/Cyberpunk: Cultures of Technological Embodiment, SAGE Publications, in association with Theory, Culture & Society, School of Human Studies, Univ. of Teesside, pp. 45–64, ISBN 9781848609143

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Holden, Stephen (26 February 1999), "'Conceiving Ada': Calling Byron's Daughter, Inventor of a Computer", New York Times

- ^ Straub, Peter (5 June 2005), "Byron's heir", Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Tom Stoppard’s 'Arcadia,' at Twenty". The New Yorker.

- ^ Profile, Gale Edwards, 1994, Director of "Arcadia" for the Sydney Theatre Company

- ^ "Ada and the Memory Engine". KQED. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Costello, Elizabeth (22 October 2015). "Ada and the Memory Engine: Love by the Numbers". SF Weekly. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Doctorow, Cory (5 October 2009). "Comic about Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage". BoingBoing. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Lovelace Lecture & Medal". BCS. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Undergraduate Lovelace Colloquium, BCSWomen". Leeds. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "BCSWomen Lovelace Colloquium". UK.

- ^ "FAQ". About. Finding Ada. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- ^ Aurora, Valerie (13 December 2011), "An update on the Ada Initiative", LWN, retrieved 5 October 2012

- ^ "Ada Byron Building".

- ^ "Conference Facilities". Ashfield District Council. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kremer, William (1 August 2013). "Crossrail: Where is it in the list of 'big digs'?". BBC News.

- ^ "FAQ – Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology". University of Oregon Libraries. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ PCH. "PCH Talks with Limor Fried". Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Davis, Anna. "New college in north London 'will boost women in tech sector'". Evening Standard. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Ada Lovelace Day: Celebrating the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and maths". FindingAda.com. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Ada Lovelace Bicentenary Lectures on Computability". Ada Lovelace Day. FindingAda.com. 20 December 2015 – 31 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "The Ada Lovelace Bicentenary Lectures on Computability". Israel Institute for Advanced Studies. 20 December 2015 – 31 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Ada Lovelace Symposium – Celebrating 200 Years of a Computer Visionary". Podcasts. UK: University of Oxford. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Ada Lovelace". UK: Science Museum, London. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Bodleian Libraries celebrates Ada Lovelace's 200th birthday with free display and Wikipedia editathons". UK: Bodleian Libraries. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Great Lives, Series 31, Konnie Huq on Ada Lovelace". BBC.

- ^ Wade, Mary Dodson. Ada Byron Lovelace: The Lady and the Computer. New York: Dillon Press, 1994.

Bibliography

- Baum, Joan (1986), The Calculating Passion of Ada Byron, Archon, ISBN 0-208-02119-1.

- Elwin, Malcolm (1975), Lord Byron's Family, John Murray.

- Essinger, James (2014), Ada's algorithm: How Lord Byron's daughter Ada Lovelace launched the digital age, Melville House Publishing, ISBN 978-1-61219-408-0.

- Fuegi, J; Francis, J (October–December 2003), "Lovelace & Babbage and the creation of the 1843 'notes'", Annals of the History of Computing, 25 (4), IEEE: 16–26, doi:10.1109/MAHC.2003.1253887.

- Hammerman, Robin; Russell, Andrew L. (2015), Ada's Legacy: Cultures of Computing from the Victorian to the Digital Age, Association for Computing Machinery and Morgan & Claypool, doi:10.1145/2809523, ISBN 9781970001518.

- Isaacson, Walter (2014), The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, Simon & Schuster.

- Kim, Eugene; Toole, Betty Alexandra (1999). "Ada and the First Computer". Scientific American. 280 (5): 76–81. Bibcode:1999SciAm.280e..76E. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0599-76.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Lewis, Judith S. (July–August 1995). "Princess of Parallelograms and her daughter: Math and gender in the nineteenth century English aristocracy". Women's Studies International Forum. 18 (4). ScienceDirect: 387–394. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(95)80030-S.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Marchand, Leslie (1971), Byron A Portrait, John Murray.

- Menabrea, Luigi Federico (1843), "Sketch of the Analytical Engine Invented by Charles Babbage", Scientific Memoirs, 3, archived from the original on 15 September 2008, retrieved 29 August 2008

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) With notes upon the memoir by the translator. - Moore, Doris Langley (1977), Ada, Countess of Lovelace, John Murray.

- Moore, Doris Langley (1961), The Late Lord Byron, Philadelphia: Lippincott, ISBN 0-06-013013-X, OCLC 358063.

- Stein, Dorothy (1985), Ada: A Life and a Legacy, MIT Press Series in the History of Computing, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-19242-X.

- Toole, Betty Alexandra (1992), Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: A Selection from the Letters of Ada Lovelace, and her Description of the First Computer, Strawberry Press, ISBN 0912647094.

- Toole, Betty Alexandra (1998), Ada, the Enchantress of Numbers: Prophet of the Computer Age, Strawberry Press, ISBN 0912647183.

- Turney, Catherine (1972), Byron's Daughter: A Biography of Elizabeth Medora Leigh, Scribner, ISBN 0684127539

- Woolley, Benjamin (February 1999), The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason, and Byron's Daughter, AU: Pan Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-72436-4, retrieved 7 April 2013.

- Woolley, Benjamin (February 2002) [1999], The Bride of Science: Romance, Reason, and Byron's Daughter, McGraw-Hill Ryerson, ISBN 978-0-07138860-3, retrieved 7 April 2013.

External links

- "Untangling the Tale of Ada Lovelace". StephenWolfram.com. 10 December 2015.

- "Ada Lovelace: Founder of Scientific Computing". Women in Science. SDSC.

- "Ada Byron, Lady Lovelace". Biographies of Women Mathematicians. Agnes Scott College.

- "Papers of the Noel, Byron and Lovelace families". UK: Archives hub.

- "Ada Lovelace & The Analytical Engine". Babbage. Computer History.

- "Ada & the Analytical Engine". Educause.

- "Ada Lovelace, Countess of Controversy". Tech TV vault. G4 TV.

- "Ada Lovelace" (streaming). In Our Time (audio). UK: The BBC (Radio 4). 6 March 2008.

- "Ada Lovelace's Notes and The Ladies Diary". Yale.

- "The fascinating story Ada Lovelace". Sabine Allaeys (Youtube).

- "Ada Lovelace, the World's First Computer Programmer, on Science and Religion". Maria Popova (Brain).

- "How Ada Lovelace, Lord Byron's Daughter, Became the World's First Computer Programmer". Maria Popova (Brain).

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ada Lovelace", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- 1815 births

- 1852 deaths

- 19th-century English mathematicians

- 19th-century women scientists

- 19th-century women writers

- Ada (programming language)

- British computer scientists

- British countesses

- Burials in Nottinghamshire

- Byron family

- Deaths from cancer in England

- Computer designers

- Daughters of barons

- Deaths from uterine cancer

- English computer programmers

- English computer scientists

- English people of Scottish descent

- English scientists

- English women poets

- Lord Byron

- Programming language designers

- Women computer scientists

- Women in engineering

- Women in technology

- Women mathematicians

- Women of the Victorian era