Age of Enlightenment

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Classicism |

|---|

|

| Classical antiquity |

| Age of Enlightenment |

| 20th-century neoclassicism |

The Age of Enlightenment or simply the Enlightenment or Age of Reason is an era from the 1620s to the 1780s in which cultural and intellectual forces in Western Europe emphasized reason, analysis, and individualism rather than traditional lines of authority. It was promoted by philosophes and local thinkers in urban coffee houses, salons, and Masonic lodges. It challenged the authority of institutions that were deeply rooted in society, especially the Roman Catholic Church; there was much talk of ways to reform society with toleration, science and skepticism.

Philosophers including Francis Bacon (1562–1626), René Descartes (1596–1650), John Locke (1632–1704), Baruch Spinoza (1632–77), Pierre Bayle (1647–1706), Giambattista Vico (1668–1744), Voltaire (1694–1778), David Hume (1711–76), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Cesare Beccaria (1738–94), Francesco Mario Pagano (1748–99) and Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727)[1] influenced society by publishing widely read works. Upon learning about enlightened views, some rulers met with intellectuals and tried to apply their reforms, such as allowing for toleration, or accepting multiple religions, in what became known as enlightened absolutism. Coinciding with the Age of Enlightenment was the Scientific revolution, spearheaded by Newton.

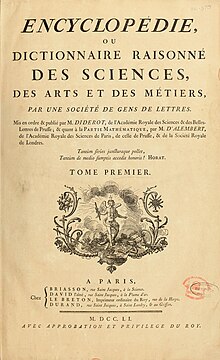

New ideas and beliefs spread around the continent and were fostered by an increase in literacy due to a departure from solely religious texts. Publications include Encyclopédie (1751–72) that was edited by Denis Diderot and (until 1759) Jean le Rond d'Alembert. Some 25,000 copies of the 35 volume encyclopedia were sold, half of them outside France. The Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary, 1764) and Letters on the English (1733) written by Voltaire (1694–1778) were revolutionary texts that spread the ideals of the Enlightenment. Some of these ideals proved influential and decisive in the course of the French Revolution, which began in 1789. After the Revolution, the Enlightenment was followed by an opposing intellectual movement known as Romanticism.

Use of the term

The term "Enlightenment" emerged in English in the later part of the 19th century,[2] with particular reference to French philosophy, as the equivalent of the French term 'Lumières' (used first by Dubos in 1733 and already well established by 1751). From Immanuel Kant's 1784 essay "Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?" ("Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?") the German term became 'Aufklärung' (aufklären = to illuminate; sich aufklären = to clear up).

However, scholars have never agreed on a definition of the Enlightenment, or on its chronological or geographical extent. Terms like "les Lumières" (French), "illuminismo" (Italian), "ilustración" (Spanish) and "Aufklärung" (German) referred to partly overlapping movements. Not until the late nineteenth century did English scholars agree they were talking about "the Enlightenment."[3][4]

Enlightenment historiography began in the period itself, from what "Enlightenment figures" said about their work. A dominant element was the intellectual angle they took. D'Alembert's Preliminary Discourse of l'Encyclopédie provides a history of the Enlightenment which comprises a chronological list of developments in the realm of knowledge – of which the Encyclopédie forms the pinnacle.[5]

A more philosophical example of this was the 1783 essay contest (in itself an activity typical of the Enlightenment) announced by the Berlin newspaper Berlinische Monatsschrift, which asked that very question: "What is Enlightenment?" Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn was among those who responded, referring to Enlightenment as a process by which man was educated in the use of reason (Jerusalem, 1783).[6]

Immanuel Kant also wrote a response, referring to Enlightenment as "man's release from his self-incurred tutelage", tutelage being "man's inability to make use of his understanding without direction from another".[7] "For Kant, Enlightenment was mankind's final coming of age, the emancipation of the human consciousness from an immature state of ignorance."[8] According to historian Roy Porter, the thesis of the liberation of the human mind from the dogmatic state of ignorance that he argues was prevalent at the time is the epitome of what the age of enlightenment was trying to capture.

According to Bertrand Russell, however, the enlightenment was a phase in a progressive development, which began in antiquity, and that reason and challenges to the established order were constant ideals throughout that time.[9] Russell argues that the enlightenment was ultimately born out of the Protestant reaction against the Catholic counter-reformation, when the philosophical views of the past two centuries crystallized into a coherent world view. He argues that many of the philosophical views, such as affinity for democracy against monarchy, originated among Protestants in the early 16th century to justify their desire to break away from the Pope and the Catholic Church. Though many of these philosophical ideals were picked up by Catholics, Russell argues, by the 18th century the Enlightenment was the principal manifestation of the schism that began with Martin Luther.[9]

Chartier (1991) argues that the Enlightenment was only invented after the fact for a political goal. He claims the leaders of the French Revolution created an Enlightenment canon of basic text, by selecting certain authors and identifying them with the Enlightenment in order to legitimize their republican political agenda.[10]

Jonathan Israel rejects the attempts of postmodern and Marxian historians to understand the revolutionary ideas of the period purely as by-products of social and economic transformations.[11] He instead focuses on the history of ideas in the period from 1650 to the end of the 18th century, and claims that it was the ideas themselves that caused the change that eventually led to the revolutions of the latter half of the 18th century and the early 19th century.[12] Israel argues that until the 1650s Western civilization "was based on a largely shared core of faith, tradition and authority".[13]

Up until this date most intellectual debates revolved around "confessional" – that is, Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed (Calvinist), or Anglican issues, and the main aim of these debates was to establish which bloc of faith ought to have the "monopoly of truth and a God-given title to authority".[14] After this date everything thus previously rooted in tradition was questioned and often replaced by new concepts in the light of philosophical reason. After the second half of the 17th century and during the 18th century a "general process of rationalization and secularization set in which rapidly overthrew theology's age-old hegemony in the world of study", and thus confessional disputes were reduced to a secondary status in favor of the "escalating contest between faith and incredulity".[14]

Time span

There is little consensus on the precise beginning of the age of Enlightenment; the beginning of the 18th century (1701) or the middle of the 17th century (1650) are often used as an approximate starting point. If taken back to the mid-17th century, the Enlightenment would trace its origins to Descartes' Discourse on Method, published in 1637. In France, many cited the publication of Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica in 1687.[15] It is argued by several historians and philosophers that the beginning of the Enlightenment is when Descartes shifted the epistemological basis from external authority to internal certainty by his cogito ergo sum published in 1637.[16][17][18]

As to its end, most scholars use the last years of the century – often choosing the French Revolution of 1789 or the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars (1804–15) as a convenient point in time with which to date the end of the Enlightenment.[19]

Furthermore, the term "Enlightenment" is anachronistic and often applied across epochs. For example, in their work Dialectic of Enlightenment, Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno see developments of the 20th century as late consequences of the Enlightenment: humans are installed as "Master" of a world being freed from its magic; truth is understood as a system; rationality becomes an instrument and an ideology managed by apparatuses; civilisation turns into the barbarism of fascism; civilizing effects of the Enlightenment turn into their opposite; and exactly this – they claim – corresponds to the problematic structure of the Enlightenment's way of thinking. Jürgen Habermas, however, disagrees with his teachers' (Adorno and Horkheimer's) view of the Enlightenment as a process of decay. He talks about an "incomplete project of modernity"[20] which, in a process of communicative actions, always asks for rational reasons.

Goals

Although Enlightenment thinkers generally shared a similar set of values, their philosophical perspectives and methodological approaches to accomplishing their goals varied in significant and sometimes contradictory ways. As Outram notes, the Enlightenment comprised "many different paths, varying in time and geography, to the common goals of progress, of tolerance, and the removal of abuses in Church and state".[21]

In his essay What is Enlightenment? (1784), Immanuel Kant described it simply as freedom to use one's own intelligence.[22] More broadly, the Enlightenment period is marked by increasing empiricism, scientific rigor, and reductionism, along with increased questioning of religious orthodoxy.

Historian Peter Gay asserts that the Enlightenment broke through "the sacred circle,"[23] whose dogma had circumscribed thinking. The Sacred Circle is a term he uses to describe the interdependent relationship between the hereditary aristocracy, the leaders of the church, and the text of the Bible. This interrelationship manifests itself as kings invoking the doctrine "Divine Right of Kings" to rule. Thus, the church sanctioned the rule of the king and in return the king defended the church.

Zafirovski (2010) argues that the Enlightenment is the source of critical ideas, such as the centrality of freedom, democracy, and reason as primary values of society – as opposed to the divine right of kings or traditions as the ruling authority.[24] This view argues that the establishment of a contractual basis of rights would lead to the market mechanism and capitalism, the scientific method, religious tolerance, and the organization of states into self-governing republics through democratic means. In this view, the tendency of the philosophes in particular to apply rationality to every problem is considered the essential change.[25] Later critics of the Enlightenment, such as the Romantics of the 19th century, contended that its goals for rationality in human affairs were too ambitious ever to be achieved.[26]

A variety of 19th-century movements, including liberalism and neo-classicism, traced their intellectual heritage back to the Enlightenment.[27]

National variations

The Enlightenment took hold in most European countries, often with a specific local emphasis. For example, in France it became associated with anti-government and anti-Church radicalism while in Germany it reached deep into the middle classes and where it expressed a spiritualistic and nationalistic tone without threatening governments or established churches.[28]

Government responses varied widely. In France, the government was hostile, and the philosophes fought against its censorship, sometimes being imprisoned or hounded into exile. The British government for the most part ignored the Enlightenment's leaders in England and Scotland although it did give Isaac Newton a knighthood and a very lucrative government office.

Enlightened absolutism

In several nations, powerful rulers – called "enlightened despots" by historians – welcomed leaders of the Enlightenment at court and asked them to help design laws and programs to reform the system, typically to build stronger national states.[29] The most prominent of those rulers were Frederick the Great of Prussia, Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796, Leopold II, who had ruled the Grand Duchy of Tuscany from 1765 to 1790, and Joseph II, Emperor of Austria from 1780 to 1790. Joseph was over-enthusiastic, announcing so many reforms that had so little support that revolts broke out and his regime became a comedy of errors and nearly all his programs were reversed.[30] Senior ministers Pombal in Portugal and Struensee in Denmark governed according to Enlightenment ideals.

Britain

Scotland

By 1750 Scotland's major cities had created an intellectual infrastructure of mutually supporting institutions such as universities, reading societies, libraries, periodicals, museums and masonic lodges.[31] The Scottish network was "predominantly liberal Calvinist, Newtonian, and 'design' oriented in character which played a major role in the further development of the transatlantic Enlightenment".[32] In France, Voltaire said "we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization," and the Scots in turn paid close attention to French ideas.[33] Historian Bruce Lenman says the Scots' "central achievement was a new capacity to recognize and interpret social patterns."[34] The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson, who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1729 to 1746. A moral philosopher who produced alternatives to the ideas of Thomas Hobbes, one of his major contributions to world thought was the utilitarian and consequentialist principle that virtue is that which provides, in his words, "the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers". Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by his protégés David Hume and Adam Smith.[35] Hume became a major figure in the skeptical philosophical and empiricist traditions of philosophy. He and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed a 'science of man',[36] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar, and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behaved in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Modern sociology largely originated from this movement,[37] and Hume's philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison (and thus the U.S. Constitution) and as popularised by Dugald Stewart, would be the basis of classical liberalism.[38] Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, often considered the first work on modern economics. It had an immediate impact on British economic policy that continues into the 21st century.[39] The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen, physician and chemist; James Anderson, an agronomist; Joseph Black, physicist and chemist; and James Hutton, the first modern geologist.[35][40]

Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, and David Hume paved the way for the modernization of Scotland and the entire Atlantic world.[41] Hutcheson, the father of the Scottish Enlightenment, championed political liberty and the right of popular rebellion against tyranny. Smith, in his monumental Wealth of Nations (1776), advocated liberty in the sphere of commerce and the global economy. Hume developed philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison and thus the U.S. Constitution.[42]

Scientific progress was influenced by, amongst others, the discovery of carbon dioxide (fixed air) by the chemist Joseph Black, the argument for deep time by the gentleman geologist James Hutton, and the invention of the steam engine by James Watt.[43] In a similar vein, the University of Edinburgh's Medical School was arguably the leading scientific institution of Europe. Students from far and wide travelled to the university to study chemistry with William Cullen, James Black, and Thomas Charles Hope, natural history with John Hope, John Walker, and Robert Jameson, and anatomy with the Alexander Monro primus, secondus, and tertius.[44]

The second stage of the Scottish Enlightenment, from the 1780s to the 1810s, consisted of a younger generation of scholars intent on popularizing the ideas of their predecessors. The end result was a reinterpretation and popularisation of the 'Scottish Enlightenment' as a set of ideals that were in turn significantly influential on liberal politics and the university systems of Britain, America and, later, Australia. The de facto leader of this movement was Dugald Stewart. Other names include Sir Walter Scott, Alexander Fraser Tytler, Sir James Hall, and John Playfair.

Dugald Stewart was a student of Adam Ferguson in Edinburgh. He then spent the years 1771 and 1772 under the instruction of Thomas Reid in Glasgow; it was Reid rather than Ferguson who was crucial to Stewart's philosophical development. From an early age, Dugald Stewart exhibited the kind of intelligence typical to a polymath. Though his main interest was philosophy, his talent for mathematics led to his job, at the age of 25, as Professor of Mathematics at Edinburgh. He held that position, initially with and then in succession to his father, Matthew Stewart. Having also substituted in the moral philosophy chair from 1778 to 1779, when Ferguson was in America working for the British government, Stewart finally took the place of his father in 1785. He held this second Chair for 25 years, and lectured so famously well that by the time of his retirement from teaching in 1810, he had developed a distinguished reputation in Europe and in North America.[45] Stewart had a huge impact on the intellectual climate of his time, partly through his lectures, partly through his writings. He attracted students from England, Europe and America, as well as domestic students, in numbers that had never been seen before. Their impact was exceptional. Lord Cockburn, a student of Stewart’s and subsequently a Scottish judge of considerable distinction, records that ‘To me Stewart’s lectures were like the opening of the heavens. I felt that I had a soul. Dugald Stewart was one of the greatest didactic orators’. Stewart lectured at the University of Edinburgh during the 1790s[46] and then took his views to the British public through his books and many essays in the progressive periodicals that circulated across the British Empire. These late Enlightenment publications, combined with his many books, went on to have a profound impact on 19th-century utilitarianism, psychology, metaphysics, political economy, and, crucially, classic liberalism.

England

Thomas Hobbes wrote the 1651 book Leviathan, which provided the foundation for social contract theory. Though he was a champion of absolutism for the sovereign, Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be "representative" and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law which leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.[47]

John Locke was one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers.[48] He influenced other thinkers such as Rousseau and Voltaire, among others. "He is one of the dozen or so thinkers who are remembered for their influential contributions across a broad spectrum of philosophical subfields – in Locke's case, across epistemology, the philosophy of language, the philosophy of mind, metaphysics, rational theology, ethics, and political philosophy."[49]

Closely associated with the 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who led the parliamentary grouping that later became the Whig party, Locke is still known today for his liberalism in political theory. He was particularly known for developing the social contract theory, an idea in political philosophy typically associated with Locke and Rousseau. The theory stated that a government and its subjects enter into an unspoken contract when that government takes power. The contract states that in exchange for some societal freedoms to the government or establishment and its laws, the subjects receive and are free to demand protection. The government’s authority lies in the consent of the governed.[50] Locke is well known for his assertion that individuals have a right to "Life, Liberty and Property", and his belief that the natural right to property is derived from labor. Tutored by Locke, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury wrote in 1706: "There is a mighty Light which spreads its self over the world especially in those two free Nations of England and Holland; on whom the Affairs of Europe now turn".[51]

Mary Wollstonecraft was one of England's earliest feminist philosophers.[52] She argued for a society based on reason, and that women, as well as men, should be treated as rational beings. She is best known for her work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1791).[53]

Thirteen American Colonies

Several Americans, especially Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, played a major role in bringing Enlightenment ideas to the new world and in influencing British and French thinkers.[54]

The Americans closely followed English and Scottish political ideas, as well as some French thinkers such as Montesquieu.[55] As deists, they were influenced by ideas of John Toland (1670–1722) and Matthew Tindal (1656–1733).[56] During the Enlightenment there was a great emphasis upon liberty, democracy, republicanism and religious tolerance. Attempts to reconcile science and religion resulted in a widespread rejection of prophecy, miracle and revealed religion in preference for Deism – especially by Thomas Paine in The Age of Reason and by Thomas Jefferson in his short Jefferson Bible – from which all supernatural aspects were removed.

Benjamin Franklin was influential in England, Scotland, and the United States[57] and France, for his political activism and for his advances in physics.[58]

The cultural exchange during the Age of Enlightenment ran in both directions across the Atlantic. Historian Charles C. Mann points out that thinkers such as Paine, Locke, and Rousseau all take Native American cultural practices as examples of natural freedom.[59]

Dutch Republic

For the Dutch the Enlightenment initially sprouted during the Dutch Golden Age. Developments during this period were to have a profound influence in the shaping of western civilization, as science, art, philosophy and economic development flourished in the Dutch Republic. Some key players in the Dutch Enlightenment were: René Descartes, originator of cogito ergo sum, Baruch Spinoza, a philosopher that wrote on pantheism and a one substance philosophy as a critique of Cartesian Dualism; Pierre Bayle, a French philosopher who advocated separation between science and religion; Eise Eisinga, an astronomer who built a planetarium; Lodewijk Meyer, a radical who claimed the Bible was obscure and doubtful; Adriaan Koerbagh, a scholar and critic of religion and conventional morality; and Burchard de Volder, a natural philosopher.[60]

Greece

The Greek Enlightenment was given impetus by wealthy Greek merchants in the major cities of the Ottoman Empire. The most important centers of Greek learning, schools and universities, were situated in Ioannina, Chios, Smyrna (İzmir) and Ayvalik.[61] The transmission of Enlightenment ideas into Greek thought also influenced the development of a national consciousness. The publication of the journal Hermes o Logios encouraged the ideas of the Enlightenment. The journal's objective was to advance Greek science, philosophy and culture. Two of the main figures of the Greek Enlightenment, Rigas Feraios and Adamantios Korais, encouraged Greek nationalists to pursue contemporary political thought.[62]

Italy

Italy was changed by the Enlightenment and it influenced Italian philosophy.[63] Enlightened thinkers often met to discuss in private salons and coffeehouses; notably in the cities of Milan, Turin and Venice. Cities with important universities such as Padua, Bologna, Naples and Rome, however, also remained great centres of scholarship and the intellect, especially Giambattista Vico (1668–1744)[64] and Antonio Genovesi.[65] Parts of Italian society also dramatically changed during the Enlightenment, with rulers such as Leopold II of Tuscany abolishing the death penalty in Tuscany. The Church's power was significantly reduced which led to a period of great thought and invention, with scientists such as Alessandro Volta and Luigi Galvani making new discoveries and greatly contributing to Western science.[63] Cesare Beccaria, the most important jurist and one of the greatest Enlightenment writers, became famous for his masterpiece Of Crimes and Punishments (1764), which was later translated into 22 languages.[63] Another prominent intellectual was Francesco Mario Pagano, who wrote important studies such as Saggi Politici (Political Essays, 1783), one of the major works of the Enlightenment in Naples, and Considerazioni sul processo criminale (Considerations on the criminal trial, 1787), which established him as an international authority on criminal law.[66]

France

In the mid-18th century, Paris became the center of an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity challenging traditional doctrines and dogmas. French historians usually place the period, called the Siècle des Lumières (Century of Enlightenments), between 1715 and 1789, from the beginning of the reign of Louis XV until the French Revolution. The philosophic movement was led by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued for a society based upon reason rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiments and observation. The political philosopher Montesquieu introduced the idea of a separation of powers in a government, a concept which was enthusiastically adopted by the authors of the United States Constitution. While the Philosophes of the French Enlightenment were not revolutionaries, and many were members of the nobility, their ideas played an important part in undermining the legitimacy of the Old Regime and shaping the French Revolution, [67]

Much of the scientific activity was based at the Louvre, where the French Academy of Sciences, founded in 1666, was located; it had separate sections for geometry, astronomy, mechanics, anatomy, chemistry and botany. Under Louis XVI new sections were added on physics, natural history and mineralogy. French scientists rivalled British scientists in mathematics and astronomy, and were ahead in chemistry and natural history. The biologist and natural historian Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon directed the Jardin des Plantes, and made it a leading center for botanic research. The mathematicians Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Jean-Charles de Borda, and Pierre-Simon Laplace; the botanist René Louiche Desfontaines, the chemists Claude Louis Berthollet, Antoine François, comte de Fourcroy and Antoine Lavoisier, all contributed to the new scientific revolution taking place in Paris. [67]

The new ideas and discoveries were publicized throughout Europe by book publishers in Paris. Between 1720 and 1780, the number of books about science and art published in Paris doubled, while the number of books about religion dropped to just one-tenth of the total. [67]

Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert published their Encyclopedie in seventeen volumes between 1751 and 1766. It provided intellectuals across Europe with a high quality survey of human knowledge. Scientists came to Paris from across Europe and from the United States to share ideas; Benjamin Franklin came in 1767 to meet with Voltaire and to talk about his experiments with electricity.

Some of the discoveries of Paris scientists, particularly in the field of chemistry, were quickly put to practical use; the experiments of Lavoisier were used to create the first modern chemical plants in Paris, and the production of hydrogen gas enabled the Montgolfier Brothers to launch the first manned flight in a hot-air balloon on 21 November 1783, from the Château de la Muette, near the Bois de Boulogne.[68]

Poland

The Age of Enlightenment reached Poland later than in Germany or Austria, as szlachta (nobility) culture (Sarmatism) together with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth political system (Golden Freedoms) were in deep crisis. The period of Polish Enlightenment began in the 1730s–1740s, peaked in the reign of Poland's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski (second half of the 18th century), went into decline with the Third Partition of Poland (1795), and ended in 1822, replaced by Romanticism in Poland. The model constitution of 1791 expressed Enlightenment ideals but was in effect for only one year as the nation was partitioned among its neighbors. More enduring were the cultural achievements, which created a nationalist spirit in Poland.[69]

Prussia and the German States

By the mid-18th century the German Enlightenment in music, philosophy, science and literature emerged as an intellectual force. Frederick the Great (1712–86), the king of Prussia 1740–1786, saw himself as a leader of the Enlightenment and patronized philosophers and scientists at his court in Berlin. He was an enthusiast for French classicism as he criticized German culture and was unaware of the remarkable advances it was undergoing. Voltaire, who had been imprisoned and maltreated by the French government, was eager to accept Frederick's invitation to live at his palace. Frederick explained, "My principal occupation is to combat ignorance and prejudice ... to enlighten minds, cultivate morality, and to make people as happy as it suits human nature, and as the means at my disposal permit."[70] Other rulers were supportive, such as Karl Friedrich, Grand Duke of Baden, who ruled Baden for 73 years (1738–1811).[71]

Christian Wolff (1679–1754) was the pioneer as a writer who expounded the Enlightenment to German readers; he legitimized German as a philosophic language.[72] Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744–1803) broke new ground in philosophy and poetry, specifically in the Sturm und Drang movement of proto-Romanticism. Weimar Classicism ("Weimarer Klassik") was a cultural and literary movement based in Weimar that sought to establish a new humanism by synthesizing Romantic, classical and Enlightenment ideas. The movement, from 1772 until 1805, involved Herder as well as polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), a poet and historian. Herder argued that every folk had its own particular identity, which was expressed in its language and culture. This legitimized the promotion of German language and culture and helped shape the development of German nationalism. Schiller's plays expressed the restless spirit of his generation, depicting the hero's struggle against social pressures and the force of destiny.[73]

German music, sponsored by the upper classes, came of age under composers such as Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791).[74]

In remote Königsberg philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) tried to reconcile rationalism and religious belief, individual freedom and political authority. As well as map out a view of the public sphere through private and public reason.[75] Kant's work contained basic tensions that would continue to shape German thought – and indeed all of European philosophy – well into the 20th century.[76]

The German Enlightenment won the support of princes, aristocrats and the middle classes and permanently reshaped the culture.[77]

Russia

In Russia the Enlightenment of the mid-eighteenth century saw the government begin to actively encourage the proliferation of arts and sciences. This era produced the first Russian university, library, theatre, public museum, and independent press. Like other enlightened despots, Catherine the Great played a key role in fostering the arts, sciences, and education. She used her own interpretation of Enlightenment ideals, assisted by notable international experts such as Voltaire (by correspondence) and, in residence, world class scientists such as Leonhard Euler, Peter Simon Pallas, Fedor Ivanovich Iankovich de Mirievo (also spelled Teodor Janković-Mirijevski), and Anders Johan Lexell. The national Enlightenment differed from its Western European counterpart in that it promoted further Modernization of all aspects of Russian life and was concerned with attacking the institution of serfdom in Russia. Historians argue that the Russian enlightenment centered on the individual instead of societal enlightenment and encouraged the living of an enlightened life.[78][79]

Spain

Charles III, king of Spain from 1759 to 1788, tried to rescue his empire from decay through far-reaching reforms such as weakening the Church and its monasteries, promoting science and university research, facilitating trade and commerce, modernizing agriculture, and avoiding wars. He was unable to control budget deficits, and borrowed more and more. Spain relapsed after his death.[80][81]

Historiography

Debates

Historian Keith Thomas says the Enlightenment has always been contested territory. He says that its supporters:

- hail it as the source of everything that is progressive about the modern world. For them, it stands for freedom of thought, rational inquiry, critical thinking, religious tolerance, political liberty, scientific achievement, the pursuit of happiness, and hope for the future.[82]

However, he adds, "its enemies accuse it of 'shallow' rationalism, naïve optimism, unrealistic universalism, and moral darkness."

Thomas points out that from the start there was a Counter-Enlightenment in which conservative and clerical defenders of traditional religion attacked materialism and skepticism as evil forces that encouraged immorality. By 1794, they pointed to the Terror during the French Revolution as confirmation of their predictions. As the Enlightenment was ending, new generations of Romantic philosophers argued that excessive dependence on reason was a mistake perpetuated by the Enlightenment, because it disregarded the powerful bonds of history, myth, faith and tradition that were necessary to hold society together.[3]

Political thought

Like the French Revolution, the Enlightenment has long been hailed as the foundation of modern Western political and intellectual culture.[84] It has been frequently linked to the French Revolution of 1789. However, as Roger Chartier points out, it was perhaps the Revolution that "invented the Enlightenment by attempting to root its legitimacy in a corpus of texts and founding authors reconciled and united ... by their preparation of a rupture with the old world".[85]

In other words, the revolutionaries elevated to heroic status those philosophers, such as Voltaire and Rousseau, who could be used to justify their radical break with the Ancien Régime. In any case, two 19th-century historians of the Enlightenment, Hippolyte Taine and Alexis de Tocqueville, did much to solidify this link of Enlightenment causing revolution and the intellectual perception of the Enlightenment itself.

An alternative view is that the "consent of the governed" philosophy as delineated by Locke in Two Treatises of Government (1689) represented a paradigm shift from the old governance paradigm under feudalism known as the "divine right of kings". In this view, the revolutions of the late 1700s and early 1800s were caused by the fact that this governance paradigm shift often could not be resolved peacefully, and therefore violent revolution was the result. Clearly a governance philosophy where the king was never wrong was in direct conflict with one whereby citizens by natural law had to consent to the acts and rulings of their government.

John Locke was able to root his governance philosophy in social contract theory, a predominant subject that permeated Enlightenment political thought. Formally, it was the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes who ushered in this new debate with his work Leviathan in 1651. Both John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed their own social contract theories in Two Treatises of Government and Discourse on Inequality, respectively. While quite different works, all three argue that a social contract is necessary for man to live in civil society.

For Hobbes, the state of nature is a state of impoverished anarchic violence in which human life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short".[86] To counter this, Hobbes argues that society enters into a social contract with itself to have an all-powerful, absolute leader, giving up a few personal liberties in exchange for security and lawfulness.

In 1689 John Locke published his Two Treatises of Government. In it, he defines his state of nature as a condition in which humans are rational and follow natural law; in which all men are born equal and with the right to life, liberty and property. However, when one citizen breaks the Law of Nature, both the transgressor and the victim enter into a state of war, from which it is virtually impossible to break free. Therefore, Locke argues that individuals enter into civil society to protect their natural rights via an “unbiased judge” or common authority, such as courts, to appeal to.

Contrastingly, Rousseau’s conception of both the state of nature and civil society, and how man moves from one to the other, relies on the supposition that civil man is corrupted. In his work Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau argues natural man is a sentient being that has no want he cannot fulfil himself. Natural man is only taken out of the state of nature when “the first man who, having enclosed a piece of ground, to whom it occurred to say this is mine, and found people sufficiently simple to believe him, was the true founder of civil society".[87] Once the inequality associated with private property is established, society is corrupted and thusly perpetuates inequality through the division of labor and, ultimately, power relations. With this in mind, Rousseau wrote On the Social Contract to spell out his contract theory. He argues that men join into civil society via the social contract to achieve unity while preserving individual freedom. This is embodied in the sovereignty of the general will, the moral and collective legislative body constituted by citizens.

Though much of Enlightenment political thought was dominated by social contract theorists, both David Hume and Adam Ferguson criticized this camp. In his essay, Of the Original Contract, Hume argues that governments derived from consent are rarely seen, rather civil government is grounded in a ruler's habitual authority and force. It is precisely because of the ruler's authority over-and-against the subject, that the subject tacitly consents; Hume argues that the subjects would "never imagine that their consent made him sovereign", rather the authority did so.[88] Similarly, Ferguson did not believe citizens built the state, rather polities grew out of social development. In his 1767 An Essay on the History of Civil Society, Ferguson uses the four stages of progress, a theory that was very popular in Scotland at the time, to explain how humans advance from a hunting and gathering society to a commercial and civil society without "signing" a social contract.

Both Rousseau and Locke's social contract theories rest on the presupposition of natural rights. A natural right is not given to man by law or custom, rather it is something that all men have in pre-political societies, and is therefore universal and inalienable. The most famous natural right formulation comes from John Locke in his Second Treatise, when he introduces the state of nature. As previously discussed, man is perfectly free in the state of nature, within the bounds of the law of nature and reason. For Locke the law of nature is grounded on mutual security, or the idea that one cannot infringe on another's natural rights, as every man is equal and has the same inalienable rights. These natural rights include perfect equality and freedom, and the right to preserve life and property.

Based on his formulation, John Locke argued against slavery on the basis that enslaving yourself goes against the law of nature; you cannot surrender your own rights, your freedom is absolute and no one can take it from you. Additionally, Locke argues that one person cannot enslave another because it is morally reprehensible. Locke does introduce a caveat in his indictment of slavery, he believes one can be made a slave during times of war and conflict because this is merely a continuation of the state of war. Therefore, one cannot sell oneself into slavery, but if one were to find oneself a lawful captive, ones enslavement would not go against ones natural rights.

Locke's theory of natural rights has influenced many political documents including the French National Constituent Assembly's Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the United States Declaration of Independence, to name a few.

In his L’Ancien Régime (1876), Hippolyte Taine traced the roots of the French Revolution back to French Classicism. However, this was not without the help of the Enlightenment view of the world, which wore down the "monarchical and religious dogma of the old regime".[89] In other words, Taine was only interested in the Enlightenment insofar as it advanced scientific discourse and transmitted what he perceived to be the intellectual legacy of French classicism.

Alexis de Tocqueville painted a more elaborate picture of the Enlightenment in L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution (1850). For de Tocqueville, the Revolution was the inevitable result of the radical opposition created in the 18th century between the monarchy and the men of letters of the Enlightenment. These men of letters constituted a sort of "substitute aristocracy that was both all-powerful and without real power". This illusory power came from the rise of "public opinion", born when absolutist centralization removed the nobility and the bourgeoisie from the political sphere. The "literary politics" that resulted promoted a discourse of equality and was hence in fundamental opposition to the monarchical regime.[90]

De Tocqueville "clearly designates ... the cultural effects of transformation in the forms of the exercise of power".[91] Nevertheless, it took another century before cultural approach became central to the historiography, as typified by Robert Darnton, The Business of Enlightenment: A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie, 1775–1800 (1979).

De Dijn argues that Peter Gay, in The Enlightenment: An Interpretation (1966), first formulated the interpretation that the Enlightenment brought political modernization to the West, in terms of introducing democratic values and institutions and the creation of modern, liberal democracies. While the thesis has many critics it has been widely accepted by Anglophone scholars and has been reinforced by the large-scale studies by Robert Darnton, Roy Porter and most recently by Jonathan Israel.[92]

Religious debate

Enlightenment era religious commentary was a response to the preceding century of religious conflict in Europe, especially the Thirty Years' War.[93] Theologians of the Enlightenment wanted to reform their faith to its generally non-confrontational roots and to limit the capacity for religious controversy to spill over into politics and warfare while still maintaining a true faith in God.

For moderate Christians, this meant a return to simple Scripture. John Locke abandoned the corpus of theological commentary in favor of an "unprejudiced examination" of the Word of God alone. He determined the essence of Christianity to be a belief in Christ the redeemer and recommended avoiding more detailed debate.[94] Thomas Jefferson in the Jefferson Bible went further; he dropped any passages dealing with miracles, visitations of angels, and the resurrection of Jesus after his death. He tried to extract the practical Christian moral code of the New Testament.[95]

Enlightenment scholars sought to curtail the political power of organized religion and thereby prevent another age of intolerant religious war.[96] Spinoza determined to remove politics from contemporary and historical theology (e.g. disregarding Judaic law).[97] Moses Mendelssohn advised affording no political weight to any organized religion, but instead recommended that each person follow what s/he found most convincing.[98] A good religion based in instinctive morals and a belief in God should not theoretically need force to maintain order in its believers, and both Mendelssohn and Spinoza judged religion on its moral fruits, not the logic of its theology.[99]

A number of novel religious ideas developed with Enlightened faith, including Deism and talk of atheism. Deism, according to Thomas Paine, is the simple belief in God the Creator, with no reference to the Bible or any other miraculous source. Instead, the Deist relies solely on personal reason to guide his creed,[100] which was eminently agreeable to many thinkers of the time.[101]

Atheism was much discussed but there were few proponents. Wilson and Reill note that, "In fact, very few enlightened intellectuals, even when they were vocal critics of Christianity, were true atheists. Rather, they were critics of orthodox belief, wedded rather to skepticism, deism, vitalism, or perhaps pantheism."[102]

Some followed Pierre Bayle and argued that atheists could indeed be moral men.[103] Many others like Voltaire held that without belief in a God who punishes evil, the moral order of society was undermined. That is, since atheists gave themselves to no Supreme Authority and no law, and had no fear of eternal consequences, they were far more likely to disrupt society.[104] Bayle (1647–1706) observed that in his day, "prudent persons will always maintain an appearance of [religion].". He believed that even atheists could hold concepts of honor and go beyond their own self-interest to create and interact in society.[105] Locke considered the consequences for mankind if there were no God and no divine law. The result would be moral anarchy. Every individual “could have no law but his own will, no end but himself. He would be a god to himself, and the satisfaction of his own will the sole measure and end of all his actions”.[106]

Intellectual history

In the meantime, though, intellectual history remained the dominant historiographical trend. The German scholar Ernst Cassirer is typical, writing in his The Philosophy of the Enlightenment (1932) that the Enlightenment was "a part and a special phase of that whole intellectual development through which modern philosophic thought gained its characteristic self-confidence and self-consciousness". Borrowing from Kant, Cassirer states that Enlightenment is the process by which the spirit "achieves clarity and depth in its understanding of its own nature and destiny, and of its own fundamental character and mission".[107] In short, the Enlightenment was a series of philosophical, scientific and otherwise intellectual developments that took place mostly in the 18th century – the birthplace of intellectual modernity.

Recent work

Only in the 1970s did interpretation of the Enlightenment allow for a more heterogeneous and even extra-European vision. A. Owen Aldridge demonstrated how Enlightenment ideas spread to Spanish colonies and how they interacted with indigenous cultures, while Franco Venturi explored how the Enlightenment took place in normally unstudied areas – Italy, Greece, the Balkans, Poland, Hungary, and Russia.[108]

Robert Darnton's cultural approach launched a new dimension of studies. He said, :

"Perhaps the Enlightenment was a more down-to-earth affair than the rarefied climate of opinion described by textbook writers, and we should question the overly highbrow, overly metaphysical view of intellectual life in the eighteenth century."[109]

Darnton examines the underbelly of the French book industry in the 18th century, examining the world of book smuggling and the lives of those writers (the "Grub Street Hacks") who never met the success of their philosophe cousins. In short, rather than concerning himself with Enlightenment canon, Darnton studies "what Frenchmen wanted to read", and who wrote, published and distributed it.[110] Similarly, in The Business of Enlightenment. A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie 1775–1800, Darnton states that there is no need to further study the encyclopædia itself, as "the book has been analyzed and anthologized dozen of times: to recapitulate all the studies of its intellectual content would be redundant".[111] He instead, as the title of the book suggests, examines the social conditions that brought about the production of the Encyclopédie. This is representative of the social interpretation as a whole – an examination of the social conditions that brought about Enlightenment ideas rather than a study of the ideas themselves.

The work of German philosopher Jürgen Habermas was central to this emerging social interpretation; his seminal work The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (published under the title Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit in 1962) was translated into English in 1989. The book outlines the creation of the "bourgeois public sphere" in 18th-century Europe. Essentially, this public sphere describes the new venues and modes of communication allowing for rational exchange that appeared in the 18th century. Habermas argued that the public sphere was bourgeois, egalitarian, rational, and independent from the state, making it the ideal venue for intellectuals to critically examine contemporary politics and society, away from the interference of established authority.

Habermas's work, though influential, has come under criticism on all fronts. While the public sphere is generally an integral component of social interpretations of the Enlightenment, numerous historians have brought into question whether the public sphere was bourgeois, oppositional to the state, independent from the state, or egalitarian.[112]

These historiographical developments have done much to open up the study of Enlightenment to a multiplicity of interpretations. In A Social History of Truth (1994), for example, Steven Shapin makes the largely sociological argument that, in 17th-century England, the mode of sociability known as civility became the primary discourse of truth; for a statement to have the potential to be considered true, it had to be expressed according to the rules of civil society.

According to Jonathan Israel, this period saw the shaping of two distinct lines of enlightenment thought:[113][114] Firstly the radical enlightenment, largely inspired by the one-substance philosophy of Spinoza, which in its political form adhered to: "democracy; racial and sexual equality; individual liberty of lifestyle; full freedom of thought, expression, and the press; eradication of religious authority from the legislative process and education; and full separation of church and state".[115]

Secondly the moderate enlightenment, which in a number of different philosophical systems, like those in the writings of Descartes, John Locke, Isaac Newton or Christian Wolff, expressed some support for critical review and renewal of the old modes of thought, but in other parts sought reform and accommodation with the old systems of power and faith.[116] These two lines of thought were again met by the conservative Counter-Enlightenment, encompassing those thinkers who held on to the traditional belief-based systems of thought.

Feminist interpretations have also appeared, with Dena Goodman being one notable example. In The Republic of Letters: A Cultural History of the French Enlightenment (1994), Goodman argues that many women in fact played an essential part in the French Enlightenment, due to the role they played as salonnières in Parisians salons. These salons "became the civil working spaces of the project of Enlightenment" and women, as salonnières, were "the legitimate governors of [the] potentially unruly discourse" that took place within.[117] On the other hand, Carla Hesse, in The Other Enlightenment: How French Women Became Modern (2001), argues that "female participation in the public cultural life of the Old Regime was ... relatively marginal".[118] It was instead the French Revolution, by destroying the old cultural and economic restraints of patronage and corporatism (guilds), that opened French society to female participation, particularly in the literary sphere.

Social and cultural interpretation

In opposition to the intellectual historiographical approach of the Enlightenment, which examines the various currents or discourses of intellectual thought within the European context during the 17th and 18th centuries, the cultural (or social) approach examines the changes that occurred in European society and culture. Under this approach, the Enlightenment is less a body of thought than a process of changing sociabilities and cultural practices – both the "content" and the processes by which this content was spread are now important. Roger Chartier describes it as follows:

This movement [from the intellectual to the cultural/social] implies casting doubt on two ideas: first, that practices can be deduced from the discourses that authorize or justify them; second, that it is possible to translate into the terms of an explicit ideology the latent meaning of social mechanisms.[119]

One of the primary elements of the cultural interpretation of the Enlightenment is the rise of the public sphere in Europe. Jürgen Habermas has influenced thinking on the public sphere more than any other, though his model is increasingly called into question. The essential problem that Habermas attempted to answer concerned the conditions necessary for "rational, critical, and genuinely open discussion of public issues". Or, more simply, the social conditions required for Enlightenment ideas to be spread and discussed. His response was the formation in the late 17th century and 18th century of the "bourgeois public sphere", a "realm of communication marked by new arenas of debate, more open and accessible forms of urban public space and sociability, and an explosion of print culture".[120] More specifically, Habermas highlights three essential elements of the public sphere:

- it was egalitarian;

- it discussed the domain of "common concern";

- argument was founded on reason.[121]

James Van Horn Melton provides a good summary of the values of this bourgeois public sphere: its members held reason to be supreme; everything was open to criticism (the public sphere is critical); and its participants opposed secrecy of all sorts.[123] This helps explain what Habermas meant by the domain of "common concern". Habermas uses the term to describe those areas of political/social knowledge and discussion that were previously the exclusive territory of the state and religious authorities, now open to critical examination by the public sphere.

Habermas credits the creation of the bourgeois public sphere to two long-term historical trends: the rise of the modern nation state and the rise of capitalism. The modern nation state in its consolidation of public power created by counterpoint a private realm of society independent of the state – allowing for the public sphere. Capitalism also increased society's autonomy and self-awareness, and an increasing need for the exchange of information. As the nascent public sphere expanded, it embraced a large variety of institutions; the most commonly cited were coffee houses and cafés, salons and the literary public sphere, figuratively localized in the Republic of Letters.[124]

Dorinda Outram further describes the rise of the public sphere. The context was the economic and social change commonly associated with the Industrial Revolution: "economic expansion, increasing urbanization, rising population and improving communications in comparison to the stagnation of the previous century"."[125] Rising efficiency in production techniques and communication lowered the prices of consumer goods at the same time as it increased the amount and variety of goods available to consumers (including the literature essential to the public sphere). Meanwhile, the colonial experience (most European states had colonial Empires in the 18th century) began to expose European society to extremely heterogeneous cultures. Outram writes that the end result was the breaking down of "barriers between cultural systems, religious divides, gender differences and geographical areas".[126] In short, the social context was set for the public sphere to come into existence.

A reductionist view of the Habermasian model has been used as a springboard to showcase historical investigations into the development of the public sphere. There are many examples of noble and lower class participation in areas such as the coffeehouses and the freemasonic lodges, demonstrating that the bourgeois-era public sphere was enriched by cross-class influences. A rough depiction of the public sphere as independent and critical of the state is contradicted by the diverse cases of government-sponsored public institutions and government participation in debate, along with the cases of private individuals using public venues to promote the status quo.

Exclusivity of the public sphere

The word "public" implies the highest level of inclusivity – the public sphere by definition should be open to all. However, as the analysis of many "public" institutions of the Enlightenment will show, this sphere was only public to relative degrees. Indeed, as Roger Chartier emphasizes, Enlightenment thinkers frequently contrasted their conception of the "public" with that of the people: Chartier cites Condorcet, who contrasted "opinion" with populace; Marmontel with "the opinion of men of letters" versus "the opinion of the multitude"; and d'Alembert, who contrasted the "truly enlightened public" with "the blind and noisy multitude".[127] In France the aristocracy played a central role in the public sphere when it moved from the King's palace at Versailles to Paris about 1720. Their rich spending stimulated the trade in luxuries and artistic creations, especially fine paintings.[128]

As Mona Ozouf underlines, public opinion was defined in opposition to the opinion of the greater population. While the nature of public opinion during the Enlightenment is as difficult to define as it is today, it is nonetheless clear that the body that held it (i.e. the public sphere) was exclusive rather than inclusive. This observation will become more apparent during the descriptions of the institutions of the public sphere, most of which excluded both women and the lower classes.[129]

Social and cultural implications in music

Because of the focus on reason over superstition, the Enlightenment cultivated the arts.[130] Emphasis on learning, art and music became more widespread, especially with the growing middle class. Areas of study such as literature, philosophy, science, and the fine arts increasingly explored subject matter that the general public in addition to the previously more segregated professionals and patrons could relate to.[131]

As musicians depended more and more on public support, public concerts became increasingly popular and helped supplement performers' and composers' incomes. The concerts also helped them to reach a wider audience. Handel, for example, epitomized this with his highly public musical activities in London. He gained considerable fame there with performances of his operas and oratorios. The music of Haydn and Mozart, with their Viennese Classical styles, are usually regarded as being the most in line with the Enlightenment ideals.[132]

Another important text that came about as a result of Enlightenment values was Charles Burney's A General History of Music: From the Earliest Ages to the Present Period, originally published in 1776. This text was a historical survey and an attempt to rationalize elements in music systematically over time.[133]

As the economy and the middle class expanded, there was an increasing number of amateur musicians. One manifestation of this involved women, who became more involved with music on a social level. Women were already engaged in professional roles as singers, and increased their presence in the amateur performers' scene, especially with keyboard music.[134]

The desire to explore, record and systematize knowledge had a meaningful impact on music publications. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Dictionnaire de musique (published 1767 in Geneva and 1768 in Paris) was a leading text in the late 18th century.[132] This widely available dictionary gave short definitions of words like genius and taste, and was clearly influenced by the Enlightenment movement. Additionally, music publishers began to cater to amateur musicians, putting out music that they could understand and play. The majority of the works that were published were for keyboard, voice and keyboard, and chamber ensemble.[134]

After these initial genres were popularized, from the mid-century on, amateur groups sang choral music, which then became a new trend for publishers to capitalize on. The increasing study of the fine arts, as well as access to amateur-friendly published works, led to more people becoming interested in reading and discussing music. Music magazines, reviews, and critical works which suited amateurs as well as connoisseurs began to surface.[134]

Although the ideals of the Enlightenment were rejected in postmodernism, they held fast in modernism and have extended well beyond the 18th century even to the present. Recently, musicologists have shown renewed interest in the ideas and consequences of the Enlightenment. For example, Rose Rosengard Subotnik's Deconstructive Variations (subtitled Music and Reason in Western Society) compares Mozart's Die Zauberflöte (1791) using the Enlightenment and Romantic perspectives, and concludes that the work is "an ideal musical representation of the Enlightenment".[133]

Separation of church and state

According to Jonathan Israel, this period saw the shaping of the "Radical Enlightenment",[113][114] which promoted the concept of separating church and state.[115] A concept that is often credited to the writings of English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704).[135] According to his principle of the social contract, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right in the liberty of conscience, which he argued must therefore remain protected from any government authority.

These views on religious tolerance and the importance of individual conscience, along with his social contract, became particularly influential in the American colonies and the drafting of the United States Constitution.[136] In which Thomas Jefferson called for a wall of separation between church and state at the federal level. He previously had supported successful efforts to disestablish the Church of England in Virginia,[137] and authored the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.[138] Thomas Jefferson's political ideals were greatly influenced by the writings of John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton[139] whom he considered the three greatest men that ever lived.[140]

Dissemination of ideas

The philosophes spent a great deal of energy disseminating their ideas among educated men and women in cosmopolitan cities. They used many venues, some of them quite new.

The Republic of Letters

The term "Republic of Letters" was coined by Pierre Bayle in 1664, in his journal Nouvelles de la Republique des Lettres. Towards the end of the 18th century, the editor of Histoire de la République des Lettres en France, a literary survey, described the Republic of Letters as being:

In the midst of all the governments that decide the fate of men; in the bosom of so many states, the majority of them despotic ... there exists a certain realm which holds sway only over the mind ... that we honour with the name Republic, because it preserves a measure of independence, and because it is almost its essence to be free. It is the realm of talent and of thought.[141]

The ideal of the Republic of Letters was the sum of a number of Enlightenment ideals: an egalitarian realm governed by knowledge that could act across political boundaries and rival state power.[141] It was a forum that supported "free public examination of questions regarding religion or legislation".[142] Immanuel Kant considered written communication essential to his conception of the public sphere; once everyone was a part of the "reading public", then society could be said to be enlightened.[143] The people who participated in the Republic of Letters, such as Diderot and Voltaire, are frequently known today as important Enlightenment figures. Indeed, the men who wrote Diderot's Encyclopédie arguably formed a microcosm of the larger "republic".[144]

Dena Goodman has argued that women played a major role in French salons – salonnières to complement the male philosophes. Discursively, she bases the Republic of Letters in polite conversation and letter writing; its principal social institution was the salon.[145]

Robert Darnton's The Literary Underground of the Old Regime was the first major historical work to critique this ideal model.[146] He argues that, by the mid-18th century, the established men of letters (gens de lettres) had fused with the elites (les grands) of French society. Consider the definition of "Goût" (taste) as written by Voltaire in the Dictionnaire philosophique (taken from Darnton): "Taste is like philosophy. It belongs to a very small number of privileged souls ... It is unknown in bourgeois families, where one is constantly occupied with the care of one's fortune". In the words of Darnton, Voltaire "thought that the Enlightenment should begin with the grands".[147] The historian cites similar opinions from d'Alembert and Louis Sébastien Mercier.[148]

Grub Street

Darnton argues that the result of this "fusion of gens de lettres and grands" was the creation of an oppositional literary sphere, Grub Street, the domain of a "multitude of versifiers and would-be authors".[149] These men, lured by the glory of the Republic of Letters, came to London to become authors, only to discover that their dreams of literary success were little more than chimeras. The literary market simply could not support large numbers of writers, who, in any case, were very poorly remunerated by the publishing-bookselling guilds.[150] The writers of Grub Street, the Grub Street Hacks, were left feeling extremely bitter about the relative success of their literary cousins, the men of letters.[151]

This bitterness and hatred found an outlet in the literature the Grub Street Hacks produced, typified by the libelle. Written mostly in the form of pamphlets, the libelles "slandered the court, the Church, the aristocracy, the academies, the salons, everything elevated and respectable, including the monarchy itself".[152] Darnton designates Le Gazetier cuirassé by Charles Théveneau de Morande as the prototype of the genre. Consider:

The devout wife of a certain Maréchal de France (who suffers from an imaginary lung disease), finding a husband of that species too delicate, considers it her religious duty to spare him and so condemns herself to the crude caresses of her butler, who would still be a lackey if he hadn't proven himself so robust.

or,

The public is warned that an epidemic disease is raging among the girls of the Opera, that it has begun to reach the ladies of the court, and that it has even been communicated to their lackeys. This disease elongates the face, destroys the complexion, reduces the weight, and causes horrible ravages where it becomes situated. There are ladies without teeth, others without eyebrows, and some are completely paralyzed.[153]

It was Grub Street literature that was most read by the reading public during the Enlightenment.[154] More importantly, Darnton argues, the Grub Street hacks inherited the "revolutionary spirit" once displayed by the philosophes, and paved the way for the Revolution by desacralizing figures of political, moral and religious authority in France.[155]

The book industry

The increased consumption of reading materials of all sorts was one of the key features of the "social" Enlightenment. Developments in the Industrial Revolution allowed consumer goods to be produced in greater quantities at lower prices, encouraging the spread of books, pamphlets, newspapers and journals – "media of the transmission of ideas and attitudes". Commercial development likewise increased the demand for information, along with rising populations and increased urbanisation.[156] However, demand for reading material extended outside of the realm of the commercial, and outside the realm of the upper and middle classes, as evidenced by the Bibliothèque Bleue. Literacy rates are difficult to gauge, but Robert Darnton writes that, in France at least, the rates doubled over the course of the 18th century.[157]

Reading underwent serious changes in the 18th century. In particular, Rolf Engelsing has argued for the existence of a Reading Revolution. Until 1750, reading was done "intensively: people tended to own a small number of books and read them repeatedly, often to small audience. After 1750, people began to read "extensively", finding as many books as they could, increasingly reading them alone.[158] This is supported by increasing literacy rates, particularly among women.[159]

Of course, the vast majority of the reading public could not afford to own a private library. And while most of the state-run "universal libraries" set up in the 17th and 18th centuries were open to the public, they were not the only sources of reading material.

On one end of the spectrum was the Bibliothèque Bleue, a collection of cheaply produced books published in Troyes, France. Intended for a largely rural and semi-literate audience these books included almanacs, retellings of medieval romances and condensed versions of popular novels, among other things. While historians, such as Roger Chartier and Robert Darnton, have argued against the Enlightenment's penetration into the lower classes, the Bibliothèque Bleue, at the very least, represents a desire to participate in Enlightenment sociability, whether or not this was actually achieved.[160]

Moving up the classes, a variety of institutions offered readers access to material without needing to buy anything. Libraries that lent out their material for a small price started to appear, and occasionally bookstores would offer a small lending library to their patrons. Coffee houses commonly offered books, journals and sometimes even popular novels to their customers. The Tatler and The Spectator, two influential periodicals sold from 1709 to 1714, were closely associated with coffee house culture in London, being both read and produced in various establishments in the city.[161] Indeed, this is an example of the triple or even quadruple function of the coffee house: reading material was often obtained, read, discussed and even produced on the premises.[162]

As Darnton describes in The Literary Underground of the Old Regime, it is extremely difficult to determine what people actually read during the Enlightenment. For example, examining the catalogs of private libraries not only gives an image skewed in favor of the classes wealthy enough to afford libraries, it also ignores censured works unlikely to be publicly acknowledged. For this reason, Darnton argues that a study of publishing would be much more fruitful for discerning reading habits.[163]

All across continental Europe, but in France especially, booksellers and publishers had to negotiate censorship laws of varying strictness. The Encyclopédie, for example, narrowly escaped seizure and had to be saved by Malesherbes, the man in charge of the French censure. Indeed, many publishing companies were conveniently located outside of France so as to avoid overzealous French censors. They would smuggle their merchandise – both pirated copies and censured works – across the border, where it would then be transported to clandestine booksellers or small-time peddlers.[164]

Darnton provides a detailed record of one clandestine bookseller's (one de Mauvelain) business in the town of Troyes. At the time, the town's population was 22,000. It had one masonic lodge and an "important" library, even though the literacy rate seems to have been less than 50 percent. Mauvelain's records give us a good representation of what literate Frenchmen might have truly read, since the clandestine nature of his business provided a less restrictive product choice. The most popular category of books was political (319 copies ordered).[165]

This included five copies of D'Holbach's Système social, but around 300 libels and pamphlets. Readers were far more interested in sensationalist stories about criminals and political corruption than they were in political theory itself. The second most popular category, "general works" (those books "that did not have a dominant motif and that contained something to offend almost everyone in authority") likewise betrayed the high demand for generally low-brow subversive literature. These works, however, like the vast majority of work produced by Darnton's "grub street hacks", never became part of literary canon, and are largely forgotten today as a result.[165]

Nevertheless, the Enlightenment was not the exclusive domain of illegal literature, as evidenced by the healthy, and mostly legal, publishing industry that existed throughout Europe. "Mostly legal" because even established publishers and book sellers occasionally ran afoul of the law. The Encyclopédie, for example, condemned not only by the King but also by Clement XII, nevertheless found its way into print with the help of the aforementioned Malesherbes and creative use of French censorship law.[166]

But many works were sold without running into any legal trouble at all. Borrowing records from libraries in England, Germany and North America indicate that more than 70 percent of books borrowed were novels; that less than 1 percent of the books were of a religious nature supports a general trend of declining religiosity.[141]

Natural history

A genre that greatly rose in importance was that of scientific literature. Natural history in particular became increasingly popular among the upper classes. Works of natural history include René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur's Histoire naturelle des insectes and Jacques Gautier d'Agoty's La Myologie complète, ou description de tous les muscles du corps humain (1746). However, as François-Alexandre Aubert de La Chesnaye des Bois's Dictionnaire de la Noblesse (1770) indicates, natural history was very often a political affair. As E. C. Spary writes, the classifications used by naturalists "slipped between the natural world and the social ... to establish not only the expertise of the naturalists over the natural, but also the dominance of the natural over the social".[167] From this basis, naturalists could then develop their own social ideals based on their scientific works.[168]

The target audience of natural history was French polite society, evidenced more by the specific discourse of the genre than by the generally high prices of its works. Naturalists catered to polite society's desire for erudition – many texts had an explicit instructive purpose. But the idea of taste (le goût) was the real social indicator: to truly be able to categorize nature, one had to have the proper taste, an ability of discretion shared by all members of polite society. In this way natural history spread many of the scientific developments of the time, but also provided a new source of legitimacy for the dominant class.[169]

Outside ancien régime France, natural history was an important part of medicine and industry, encompassing the fields of botany, zoology, meteorology, hydrology and mineralogy. Students in Enlightenment universities and academies were taught these subjects to prepare them for careers as diverse as medicine and theology. As shown by M D Eddy, natural history in this context was a very middle class pursuit and operated as a fertile trading zone for the interdisciplinary exchange of diverse scientific ideas.[44]

Scientific and literary journals

The many scientific and literary journals (predominantly composed of book reviews) that were published during this time are also evidence of the intellectual side of the Enlightenment. In fact, Jonathan Israel argues that the learned journals, from the 1680s onwards, influenced European intellectual culture to a greater degree than any other "cultural innovation".[170]

The first journal appeared in 1665– the Parisian Journal des Sçavans – but it was not until 1682 that periodicals began to be more widely produced. French and Latin were the dominant languages of publication, but there was also a steady demand for material in German and Dutch. There was generally low demand for English publications on the Continent, which was echoed by England's similar lack of desire for French works. Languages commanding less of an international market – such as Danish, Spanish and Portuguese – found journal success more difficult, and more often than not, a more international language was used instead. Although German did have an international quality to it, it was French that slowly took over Latin's status as the lingua franca of learned circles. This in turn gave precedence to the publishing industry in Holland, where the vast majority of these French language periodicals were produced.[171]