Ales Bialiatski

Ales Bialiatski | |

|---|---|

Алесь Бяляцкі | |

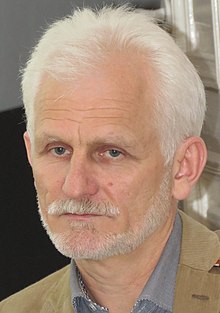

Bialiatski in 2015 | |

| Born | 25 September 1962 |

| Other names | Aliaksandr Bialiatski[citation needed] |

| Education | Gomel State University (BA) |

| Occupation | https://freeales.org/en# |

| Employer | Viasna Human Rights Centre |

| Spouse | Natallia Pinchuk |

| Awards |

|

Ales Viktaravich Bialiatski[a] (Belarusian: Алесь Віктаравіч Бяляцкі, romanized: Aleś Viktaravič Bialacki; born 25 September 1962) is a Russian-born Belarusian pro-democracy activist and prisoner of conscience known for his work with the Viasna Human Rights Centre. An activist for Belarusian independence and democracy since the early 1980s, Bialiatski is a founding member of Viasna and the Belarusian Popular Front, serving as leader of the latter from 1996 to 1999. He is also a member of the Coordination Council of the Belarusian opposition. He has been called "a pillar of the human rights movement in Eastern Europe" by The New York Times, and recognised as a prominent pro-democracy activist in Belarus.

Bialiatski's defence of human rights in Belarus has brought him numerous international accolades. In 2020, he won the Right Livelihood Award, widely known as the "Alternative Nobel Prize". In 2022, Bialiatski was awarded the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, along with the organisations Memorial and Centre for Civil Liberties.

Bialiatski has been imprisoned twice; firstly from 2011 to 2014, and currently since 2021, on both occasions on charges of tax evasion. Bialiatski, as well as other human rights activists, have called the charges politically motivated.

On 3 March 2023, Bialiatski was sentenced in Minsk to ten years in prison for "cash smuggling" as well as "financing actions and groups that grossly violated public order." Human rights activists view the charges as fabricated in order to silence Bialiatski and his movement after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[1]

Life

[edit]Background

[edit]Bialiatski was born in Vyartsilya, in today's Karelia, Russia, to Belarusian parents.[2] His father Viktar Bialiatski is a native of the Rahačoŭ District, and his mother Nina comes from the Naroŭlia District. In 1965, the family returned to Belarus to settle in Svietlahorsk, Gomel Region.

Bialiatski is a scholar of Belarusian literature[2] and graduated from Homiel State University in 1984 with a degree in Russian and Belarusian Philology. After graduation, Bialiatski worked as a schoolteacher in the Lieĺčycy District in Gomel Region.[citation needed]

From 1985 to 1986, he served in the army as an armoured vehicle driver in an antitank artillery battalion near Yekaterinburg (then Sverdlovsk), Russia.[3]

In Belarus

[edit]Bialiatski was Secretary of the Belarusian Popular Front (1996–1999) and deputy chairman of the BPF (1999–2001).[2]

Bialiatski founded the Viasna Human Rights Centre in 1996. The Minsk-based organization which was then called “Viasna-96”, was transformed into a nationwide NGO in June 1999. On 28 October 2003 the Supreme Court of Belarus cancelled the state registration of the Viasna Human Rights Centre for its role in the observation of the 2001 presidential election. Since then, the leading Belarusian human rights organization has been working without registration.[4]

Bialiatski was chairman of the Working Group of the Assembly of Democratic NGOs (2000–2004). In 2007–2016, he was vice-president of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH).[5]

Bialiatski is a member of the Union of Belarusian Writers (since 1995) and the Belarusian PEN-Centre (since 2009).[2]

August 2011 arrest and sentencing

[edit]On 4 August 2011, Bialiatski was arrested under charges of tax evasion (“concealment of profits on an especially large scale”, Article 243, part 2 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Belarus).[6] The indictment was made possible by financial records released by prosecutors in Lithuania and Poland.[7]

On 24 October 2011, Bialiatski was sentenced to 4½ years in prison and confiscation of property. Bialiatski pleaded not guilty, saying that the money had been received on his bank accounts to cover Viasna's human rights activities.[8]

Reaction

[edit]Belarusian human rights activists, as well as the European Union leaders, EU governments, and the United States said that Bialiatski was a political prisoner, calling his sentencing politically motivated. They urged the Belarusian authorities to release the human rights activist. On 15 September 2011 a special resolution the European Parliament called for Bialiatski's immediate release.[9] The activist's release was also requested by EP President Jerzy Buzek,[10] EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Catherine Ashton, OSCE Chairman Eamon Gilmore,[11] and the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti.[12]

Several international human rights non-governmental organisations called for Bialiatski's "immediate and unconditional release".

- On 11 August, Amnesty International declared Bialiatski a prisoner of conscience.[13]

- On 12 September, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) launched a campaign to advocate for Bialiatski's release and inform more generally about political prisoners in Belarus.[14]

- Tatsiana Reviaka, Bialiatski's colleague at Viasna and the President of the Belarusian Human Rights House in Vilnius, said that "the reason behind these charges is the fact that our organisation Viasna has been providing different assistance to victims of political repressions in Belarus.[15]

- "Belyatsky's arrest is a clear case of retaliation against him and Viasna for their human rights work. It's the latest in a long series of efforts by the government to crush Belarus's civil society", Human Rights Watch said in a statement.[16]

Bialiatski served his sentence in penal colony number 2 in the city of Babruysk, working as a packer in a sewing shop.[citation needed]

He was repeatedly punished by the prison administration for "violation of the prison rules", and was declared a "malicious offender", which prevented him from being amnestied in 2012 and deprived him of family visits and food parcels.[citation needed]

During his time in prison, Bialiatski wrote many texts on literary topics, essays, memoirs, which were posted to his associates.[citation needed]

An unprecedented campaign of international solidarity was launched during his imprisonment. Bialiatski was released from prison 20 months ahead of schedule on 21 June 2014 after spending 1,052 days of arbitrary detention in harsh conditions, including serving periods of solitary confinement.[17]

The date of Bialiatski's arrest, 4 August, is celebrated annually as the International Day of Solidarity with the Civil Society of Belarus. It was established in 2012 as a response to the activist's arrest.[18]

Release in 2014 and arrest in 2021

[edit]Bialiatski was released on 21 June 2014.[19] The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus, Miklós Haraszti welcomed his liberation.[20]

During the 2020 Belarusian protests, he became a member of the Coordination Council of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya.[21]

On 14 July 2021, the Belarusian police searched Viasna's employees' homes around the country and raided the central office. Bialiatski and his colleagues Vladimir Stephanovich and Vladimir Labkovich were arrested.[22][23] On 6 October 2021, Bialiatski was charged with tax evasion with a maximum penalty of 7 years in prison.[24] As of 7 October 2022, he was still in prison.[25]

2023 trial and sentencing

[edit]His trial alongside Valentin Stefanovich and Vladimir Labkovich started in January 2023.[26][27] Amnesty International mentioned that "[t]he trial against Ales Bialiatski and his fellow human rights defenders is a blatant act of injustice wherein the state is clearly seeking to enact revenge for their activism. In this shameful pretense of a trial, the defendants cannot even hope for a semblance of justice."[28]

On 3 March 2023, the Belarus judicial system convicted Bialiatski of smuggling and financing political protests, as "actions grossly violating public order", and sentenced him to prison for 10 years.[29][30]

International recognition

[edit]

Referred to by The New York Times as "a pillar of the human rights movement in Eastern Europe since the late 1980s,"[31] Bialiatski has received widespread international recognition as a prominent voice for human rights activism in Belarus.[25]

Bialiatski's work has been recognised by human rights organisations globally. In March 2006, Bialiatski and Viasna won the 2005 Homo Homini Award of the Czech NGO People in Need, which recognizes "an individual who is deserving of significant recognition due to their promotion of human rights, democracy and non-violent solutions to political conflicts".[32] The prize was awarded by former Czech President and dissident Václav Havel. In 2006, Bialiatski won the Swedish Per Anger Prize,[33] as well as the Andrei Sakharov Freedom Award of the Norwegian Helsinki Committee.[34]

In 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe awarded him its Václav Havel Human Rights Prize for his work as a human rights defender, "so that the citizens of Belarus may one day aspire to our European standards".[35] As he was detained at the time, the award was received on his behalf by his wife. After his release, he visited Strasbourg to thank the Assembly for its support.[36] He was also awarded the Lech Wałęsa Award for "democratisation of the Republic of Belarus, his active promotion of human rights and aid provided for persons currently persecuted by Belarusian authorities" that year,[37] as well as, together with Uganda's Civil Society Coalition on Human Rights and Constitutional Law, the 2011 Human Rights Defenders Award by the United States Department of State. As he was still imprisoned at the time of the Ales Bialiatski was awarded the prize in absentia, and the award was passed to his wife, Natallia Pinchuk, in the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw, Poland on 25 September 2012.[38]

Bialiatski was declared civil rights defender of the year by the Swedish Civil Rights Defenders group in 2014.[39] In 2020, he shared Right Livelihood Award, widely known as "Alternate Nobel Prize" with Nasrin Sotoudeh, Bryan Stevenson, and Lottie Cunningham Wren.[40] In December of the same year, Bialiatski was named among the representatives of the Belarusian opposition, and honored with the Sakharov Prize by the European Parliament.[41]

Bialiatski has received honorary citizenship from the cities of Genoa (in 2010),[42] Paris (in 2012),[43] and Syracuse, Sicily (in 2014).[44]

In 2022, Bialiatski was awarded the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize along with organisations Memorial and Centre for Civil Liberties.[45] Prior to his 2022 award of the Nobel Peace Prize, Bialiatski was nominated five times unsuccessfully,[46] including in 2006 and 2007. In 2012, he was again nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, but the prize was awarded to the European Union. In February 2013, he was nominated by the Norwegian MP Jan Tore Sanner. In 2014, members of the Polish Parliament nominated Bialiatski for the Nobel Peace Prize. The nomination was signed by 160 Polish MPs.[citation needed]

Following the awarding of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize, members of the Belarusian opposition celebrated it, with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya saying in a Tweet, "The prize is an important recognition for all Belarusians fighting for freedom & democracy. All political prisoners must be released without delay."[47]

References in art and media

[edit]Viktar Sazonau's book "The Poetry of the Prose", 2013, has a dedication to Ales Bialiatski. One of the stories in book entitled "A Postcard from the Political Prisoner Postcard" is based on Bialiatski's experience .[48]

Uladzimir Siuchykau's essay "The Sweet Word of Freedom!" published in the compilation "Night Notes". Appendix "Literary Belarus" No. 4 (92) in the newspaper "Novy Chas". 25 April 2014 / No. 16 (385).[49]

Uladzimir Niakliayeu’s poem "Rymtseli" dedicated to the 50th anniversary of human rights defender Ales Bialiatski.[50]

Siarzhuk Sys's poem "To Ales Bialiatski".[51]

Mikhas Skobla's essay "A Letter to Ales Bialiatski".[52]

Feature film "Vyshe Neba" ("Above the Sky", directed by Dmitry Marinin and Andrey Kureychik, 2012) features an episode depicting Ales Bialiatski's arrest shown in the news of the TV channel Belarus-1 (56th minute).[53]

Documentary "Ales Bialiatski’s Candle of Truth" (written by Palina Stsepanenka, 2011, Belarus).[54]

Documentary "Spring" (directed by Volha Shved, 2012, Belarus).[55]

Documentary "A Heart That Never Dies" (directed by Erling Borgen, 2015, Norway).[56]

Documentary "1,050 days of Solitude" (director Aleh Dashkevich, 2014 Belarus).[57]

Artist Ai Weiwei constructed Ales Bialiatski's portrait from Lego bricks. The work was displayed at the exhibition "Next" in the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC.[58]

Bibliography

[edit]- «Літаратура і нацыя». 1991.[59]

- «Прабежкі па беразе Жэнеўскага возера». 2006.[citation needed]

- «Асьвечаныя беларушчынай». 2013.[60]

- «Іртутнае срэбра жыцьця». 2014.[61]

- «Халоднае крыло Радзімы». 2014.[62]

- «Бой з сабой». 2016.[63]

- 20-Я Вясна. Зборнік эсэ і ўспамінаў сяброў Праваабарончага цэнтра «Вясна». 2016. (А. Бяляцкі. с. 7-20; 189–203.[64])

Personal life

[edit]Ales Bialiatski is married to Natallia Pinchuk. They met in 1982 when Ales was a student of Francishak Skaryna Homiel State University and Nataliia studied in the pedagogical college in Lojeu. The couple married in 1987. Ales Bialiatski has a son named Adam.[citation needed] He is a practising Roman Catholic.[65]

During his university years, Bialiatski played bass guitar in a band called Baski. He has stated that his two major hobbies now are mushroom hunting and planting flowers. He generally speaks the Belarusian language.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Alternatively transliterated as Ales Bialacki, Ales Byalyatski, Alies Bialiacki, and Alex Belyatsky

References

[edit]- ^ "Ales Bialiatski: Nobel Prize-winning activist sentenced to 10 years in jail". BBC News. 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d A. Tamkovich (2014) Contemporary History in Faces. р.165-173. ББК 84 УДК 823 Т 65 Tamkovich (2014) Press release, Human Rights House Foundation

- ^ "Nobel Peace Prize: Who is Ales Bialiatski?". BBC News. 7 October 2022. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "About Viasna". Viasna Human Rights Centre. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski reelected FIDH Vice-President". www.fidh.org. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski: Two years since politically motivated verdict". spring96.org. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "The Norwegian Helsinki Committee demands the immediate release of Ales Bialiatski". spring96.org. 10 August 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Results of monitoring of trial of Ales Bialiatski". spring96.org. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "European Parliament resolution on Belarus: the arrest of human rights defender Ales Bialatski". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "EP President urges to release Byalyatski and other political prisoners". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Bialiatski should be set free, says OSCE Chairperson". osce.org. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "UN expert urges authorities to release Ales Bialiatski". news.un.org. 2 August 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ [Belarus must free activist held on tax evasion charges]

- ^ [International mobilisation of the FIDH network to demand the release of Ales Bialiatski]

- ^ [Call for immediate and unconditional release of Ales Bialiatski]

- ^ [Belarus: Leading Rights Defender Detained]

- ^ [Ales Bialiatski Free at Last!]

- ^ [The International Day of Solidarity with the Civil Society of Belarus]

- ^ "Belarus: Human Rights Defender Freed". HRW. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ "Belarus: "Rights defender Ales Bialiatski released, but other political prisoners remain in jail" – UN expert". Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ "Члены Координационного Совета" [Members of the Coordinating Council]. rada.vision. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Perunovskaya, A. (22 October 2021). "100 дней ареста. О чем пишет Алесь Беляцкий из тюрьмы?" [100 Days in Prison: What Does Ales Bialiatski Write from His Cell?] (in Russian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ "Belarus: arbitrarily detained for over a month, Viasna's members must be released". FIDH. 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Kruope, A. (7 October 2021). "Belarus Authorities 'Purge' Human Rights Defenders". HRW. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Ales Bialiatski: Who is the Nobel Peace Prize winner?". BBC. 7 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Belarus puts Nobel Peace Prize winner on trial", Politico, 5 January 2023, retrieved 5 January 2023

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski: Nobel Prize-winning activist stands trial in Belarus", BBC News, 5 January 2023, retrieved 5 January 2023

- ^ "Belarus: Trial against Nobel Peace Prize laureate Ales Bialiatski a 'shameful pretense' of justice", Amnesty International, 5 January 2023, retrieved 5 January 2023

- ^ "Belarus court jails Nobel Peace Prize winner Bialiatski for 10 years". Reuters. 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski: Nobel Prize-winning activist sentenced to 10 years in jail". BBC News. 3 March 2023. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (7 October 2022). "The Belarusian laureate is a longtime pillar of Eastern Europe's human rights movement". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Homo Homini Award". People in Need. 2005. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ ["Aliaksandr Bialiatski, Belarus" (PDF). Eastern Partnership. 2009. Retrieved 3 June 2011.]

- ^ "The Norwegian Helsinki Committee demands the immediate release of Ales Bialiatski". Viasna Human Rights Centre. 10 August 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Václav Havel Human Rights Prize 2013 awarded to Ales Bialiatski". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 30 September 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ "EU-Belarus: Meeting with Ales Bialiatski in Strasbourg". European Commission. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Ales Belyatsky laureate of the 2012 Lech Wałęsa Award". Lech Walesa Institute. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski awarded US Department of State's 2011 Human Rights Defenders Prize". Viasna Human Rights Centre. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Civil Rights Defender of the Year 2014 – Ales Bialiatski". crd.org. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ "Belarusian pro-democracy activist Ales Bialiatski receives 2020 Right Livelihood Award". Right Livelihood Award. October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Belarusian opposition receives 2020 Sakharov Prize". European Parliament. 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski became honorary citizen of Genoa". Viasna Human Rights Centre. 20 July 2010. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski received at Paris Mayor's Office and French MFA". Viasna Human Rights Centre. 8 July 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski becomes honorary citizen of Syracuse". Viasna Human Rights Centre. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 2022". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski nominated for Nobel Peace Prize again". spring96.org. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ Picheta, Rob (7 October 2022). "Human rights advocates from Russia, Ukraine and Belarus share Nobel Peace Prize". CNN. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ [Паэзія прозы] / Prose poetry.

- ^ [Гэта салодкае слова - свабода!] / This sweet word is freedom!

- ^ [РЫМЦЕЛІ. Алесю Бяляцкаму] / THE ROMANS. Ales Bialiatskyi

- ^ [Алесю Бяляцкаму] / Ales Bialiatskyi

- ^ [Ліст да Алеся Бяляцкага] / A letter to Ales Bialiatski

- ^ [«Выше неба»] / "Above the sky"

- ^ [«Сьвечка праўды Алеся Бяляцкага»] / "Ales Bialiatski's candle of truth"

- ^ [«Вясна», дак. фільм пра Алеся Бяляцкага.] / "Spring", doc. a film about Ales Bialiatski.

- ^ "A Heart That Never Dies. A Series About Civil Courage & Human Rights". www.aheartthatneverdies.tv. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ [1050 дзён самоты] / 1050 days of solitude

- ^ [Ai Weiwei: Trace at Hirshhorn]

- ^ [Літаратура і нацыя.] / Literature and the nation.

- ^ [Асьвечаныя беларушчынай.] / Sanctified by Belarushchyna.

- ^ [Іртутнае срэбра жыцьця.] / Mercurial silver of life.

- ^ [Халоднае крыло Радзімы.] / The cold wing of the Motherland.

- ^ [Бой з сабой] / Fight with yourself

- ^ [20-Я Вясна.] / 20th Spring.

- ^ "Ales Bialiatski, Premio Nobel de la Paz: un revitalizador de la comunidad católica bielorrusa". Religión en Libertad (in Spanish). 17 November 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

External links

[edit]- 1962 births

- Living people

- Amnesty International prisoners of conscience held by Belarus

- Belarusian dissidents

- Belarusian human rights activists

- Belarusian Nobel laureates

- Belarusian prisoners and detainees

- Belarusian democracy activists

- Belarusian Roman Catholics

- Belarusian male writers

- International Federation for Human Rights

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- Per Anger Prize

- Political prisoners according to Viasna Human Rights Centre

- Václav Havel Human Rights Prize laureates