Angkor: Difference between revisions

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

[[Image:Guimet IMG 6009 Jayavarman7.JPG|thumb|right|upright|Portrait of Jayavarman VII on display at [[Musee Guimet]], Paris.]] |

[[Image:Guimet IMG 6009 Jayavarman7.JPG|thumb|right|upright|Portrait of Jayavarman VII on display at [[Musee Guimet]], Paris.]] |

||

Following the death of Suryavarman around [[1150]] A.D., the kingdom fell into a period of internal strife. Its neighbors to the east, the [[Cham people|Cham]] of what is now southern Vietnam, took advantage of the situation in [[1177]] to launch a seaborne invasion up the [[Mekong River]] and across [[Tonle Sap]]. The Cham forces were successful in sacking the Khmer capital of [[Yasodharapura]] and in killing the reigning king. However, a Khmer prince who was to become King [[Jayavarman VII]] rallied his people and defeated the Cham in battles on the lake and on the land. In [[1181]], Jayavarman assumed the throne. He was to be the greatest of the Angkorian kings.<ref>Higham, ''The Civilization of Angkor'', pp.120 ff.</ref> Over the ruins of Yasodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of [[Angkor Thom]], as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the temple known as the [[Bayon]]. Bas-reliefs at the Bayon depict not only the king's battles with the Cham, but also scenes from the life of Khmer villagers and courtiers. In addition, Jayavarman constructed the well-known temples of [[Ta Prohm]] and [[Preah Khan]], dedicating them to his parents. This massive program of construction coincided with a transition in the state religion from [[Hinduism]] to [[Mahayana Buddhism]], since Jayavarman himself had adopted the latter as his personal faith. During Jayavarman's reign, Hindu temples were altered to display images of the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]], and Angkor Wat briefly became a Buddhist shrine. Following his death, a Hindu revival included a large-scale campaign of desecrating Buddhist images, until [[Theravada Buddhism]] became established as the land's dominant religion from the [[14th century]].<ref>Higham, ''The Civilization of Angkor'', p.116.</ref> |

Following the death of Suryavarman around [[1150]] A.D., the kingdom fell into a period of internal strife. Its neighbors to the east, the [[Cham people|Cham]] of what is now southern Vietnam, took advantage of the situation in [[1177]] to launch a seaborne invasion up the [[Mekong River]] and across [[Tonle Sap]]. The Cham forces were successful in sacking the Khmer capital of [[Yasodharapura]] and in killing the reigning king. However, a Khmer prince who was to become King [[Jayavarman VII]] rallied his people and defeated the Cham in battles on the lake and on the land. In [[1181]], Jayavarman assumed the throne. He was to be the greatest of the Angkorian kings.<ref>Higham, ''The Civilization of Angkor'', pp.120 ff.</ref> Over the ruins of Yasodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of [[Angkor Thom]], as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the temple known as the [[Bayon]]. Bas-reliefs at the Bayon depict not only the king's battles with the Cham, but also scenes from the life of Khmer villagers and courtiers. In addition, Jayavarman constructed the well-known temples of [[Ta Prohm]] and [[Preah Khan]], dedicating them to his parents. This massive program of construction coincided with a transition in the state religion from [[Hinduism]] to [[Mahayana Buddhism]], since Jayavarman himself had adopted the latter as his personal faith. During Jayavarman's reign, Hindu temples were altered to display images of the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]], and Angkor Wat briefly became a Buddhist shrine. Following his death, a Hindu revival included a large-scale campaign of desecrating Buddhist images, until [[Theravada Buddhism]] became established as the land's dominant religion from the [[14th century]].<ref>Higham, ''The Civilization of Angkor'', p.116.</ref> |

||

LOVE LOVE |

|||

===Report of Zhou Daguan, Chinese Diplomat=== |

===Report of Zhou Daguan, Chinese Diplomat=== |

||

Revision as of 03:33, 28 March 2008

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 668 |

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) |

| Endangered | 1992-2004 |

Angkor is a name conventionally applied to the region of Cambodia serving as the seat of the Khmer empire that flourished from approximately the 9th century to the 15th century A.D. (The word "Angkor" itself is derived from the Sanskrit "nagara," meaning "city.")[1] More precisely, the Angkorian period may be defined as the period from 802 A.D., when the Khmer Hindu monarch Jayavarman II declared himself the "universal monarch" and "god-king" of Cambodia, until 1431 A.D., when Thai invaders sacked the Khmer capital, causing its population to migrate south to the area of Phnom Penh.

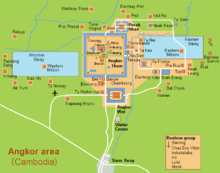

The ruins of Angkor are located amid forests and farmland to the north of the Great Lake (Tonle Sap) and south of the Kulen Hills, near modern day Siem Reap (13°24'N, 103°51'E), and are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The temples of the Angkor area number over one thousand, ranging in scale from nondescript piles of brick rubble scattered through rice fields to the magnificent Angkor Wat, said to be the world's largest single religious monument. Many of the temples at Angkor have been restored, and together they comprise the most significant site of Khmer architecture. Visitor numbers approach one million annually.

In 2007 an international team of researchers using satellite photographs and other modern techniques concluded that Angkor had been the largest preindustrial city in the world with an urban sprawl of 1,150 square miles. The closest rival to Angkor, the Mayan city of Tikal in Guatemala, was roughly 50 square miles in total size.[2]

Historical Overview

Origin of Angkor as the Seat of the Khmer Empire

The Angkorian period may be said to have begun shortly after 800 CE, when the Khmer King Jayavarman II announced the independence of Kambujadesa (Cambodia) from Java and established his capital of Hariharalaya (now known as "Roluos") at the northern end of Tonle Sap. Through a program of military campaigns, alliances, marriages and land grants, he achieved a unification of the country bordered by China (to the north), Champa (now Central Vietnam, to the east), the ocean (to the south) and a place identified by a stone inscription as "the land of cardamoms and mangoes" (to the west). In 802 Jayavarman articulated his new status by declaring himself "universal monarch" (chakravartin), and, in a move that was to be imitated by his successors and that linked him to the cult of Siva, taking on the epithet of "god-king" (devaraja).[3] Before Jayavarman's tour de force, Cambodia had consisted in a number of politically independent principalities collectively known to the Chinese by the names Funan and Chenla.[4]

In 889 CE, Yasovarman I ascended to the throne.[5] A great king and an accomplished builder, he was celebrated by one inscription as "a lion-man; he tore the enemy with the claws of his grandeur; his teeth were his policies; his eyes were the Veda."[6] Near the old capital of Hariharalaya, Yasovarman constructed a new city called Yasodharapura. In the tradition of his predecessors, he constructed also a massive reservoir called a baray. The significance of such reservoirs has been debated by modern scholars, some of whom have seen in them a means of irrigating rice fields, and others of whom have regarded them as religiously charged symbols of the great mythological oceans surrounding Mount Meru, the abode of the gods. The mountain, in turn, was represented by an elevated temple, in which the "god-king" was represented by a lingam.[7] In accordance with this cosmic symbolism, Yasovarman built his central temple on a low hill known as Phnom Bakheng, surrounding it with a moat fed from the baray. He also built numerous other Hindu temples and ashramas, or retreats for ascetics.[8]

Over the next 300 years, between 900 and 1200 CE, the Khmer empire produced some of the world's most magnificent architectural masterpieces in the area known as Angkor. Most are concentrated in an area approximately 15 miles east to west and 5 miles north to south, although the Angkor Archaeological Park which administers the area includes sites as far away as Kbal Spean, about 30 miles to the north. Some 72 major temples or other buildings dot the area. The medieval settlement around the temple complex was approximately 3,000 sq km (1,150 sq miles), roughly the size of modern Los Angeles. This makes it the largest pre-industrial complex of its type, easily surpassing the nearest claim, that of the Maya city of Tikal.[9]

Suryvarman II and the Construction of Angkor Wat

The principal temple of the Angkorian region, Angkor Wat, was built between 1113 and 1150 by King Suryavarman II. Suryavarman ascended to the throne after prevailing in a battle with a rival prince. An inscription says that in the course of combat, Suryavarman lept onto his rival's war elephant and killed him, just as the mythical bird-man Garuda slays a serpent.[10]

After consolidating his political position through military campaigns, diplomacy, and a firm domestic administration, Suryavarman launched into the construction of Angkor Wat as his personal temple mausoleum. Breaking with the tradition of the Khmer kings, and influenced perhaps by the concurrent rise of Vaisnavism in India, he dedicated the temple to Vishnu rather than to Siva. With walls nearly one-half mile long on each side, Angkor Wat grandly portrays the Hindu cosmology, with the central towers representing Mount Meru, home of the gods; the outer walls, the mountains enclosing the world; and the moat, the oceans beyond. The traditional theme of identifying the Cambodian devaraja with the gods, and his residence with that of the celestials, is very much in evidence. The measurements themselves of the temple and its parts in relation to one another have cosmological significance.[11] Suryavarman had the walls of the temple decorated with bas reliefs depicting not only scenes from mythology, but also from the life of his own imperial court. In one of the scenes, the king himself is portrayed as larger in size than his subjects, sitting cross legged on an elevated throne and holding court, while a bevy of attendants make him comfortable with the aid of parasols and fans.

Jayavarman VII, the Greatest of the Angkorian Kings

Following the death of Suryavarman around 1150 A.D., the kingdom fell into a period of internal strife. Its neighbors to the east, the Cham of what is now southern Vietnam, took advantage of the situation in 1177 to launch a seaborne invasion up the Mekong River and across Tonle Sap. The Cham forces were successful in sacking the Khmer capital of Yasodharapura and in killing the reigning king. However, a Khmer prince who was to become King Jayavarman VII rallied his people and defeated the Cham in battles on the lake and on the land. In 1181, Jayavarman assumed the throne. He was to be the greatest of the Angkorian kings.[12] Over the ruins of Yasodharapura, Jayavarman constructed the walled city of Angkor Thom, as well as its geographic and spiritual center, the temple known as the Bayon. Bas-reliefs at the Bayon depict not only the king's battles with the Cham, but also scenes from the life of Khmer villagers and courtiers. In addition, Jayavarman constructed the well-known temples of Ta Prohm and Preah Khan, dedicating them to his parents. This massive program of construction coincided with a transition in the state religion from Hinduism to Mahayana Buddhism, since Jayavarman himself had adopted the latter as his personal faith. During Jayavarman's reign, Hindu temples were altered to display images of the Buddha, and Angkor Wat briefly became a Buddhist shrine. Following his death, a Hindu revival included a large-scale campaign of desecrating Buddhist images, until Theravada Buddhism became established as the land's dominant religion from the 14th century.[13] LOVE LOVE

Report of Zhou Daguan, Chinese Diplomat

The year 1296 marked the arrival at Angkor of the Chinese diplomat Zhou Daguan. Zhou's one-year sojourn in the Khmer capital during the reign of King Indravarman III is historically significant, because he penned a still-surviving account of approximately 40 pages detailing his observations of Khmer society. Some of the topics he addressed in the account were those of religion, justice, kingship, agriculture, slavery, birds, vegetables, bathing, clothing, tools, draft animals, and commerce. In one passage, he described a royal procession consisting of soldiers, numerous servant women and concubines, ministers and princes, and finally "the sovereign, standing on an elephant, holding his sacred sword in his hand." Together with the inscriptions that have been found on Angkorian stelas, temples and other monuments, and together with the bas-reliefs at the Bayon and Angkor Wat, Zhou's journal is our most significant source of information about everyday life at Angkor. Filled as it is with vivid anecdotes and sometimes incredulous observations of a civilization that struck Zhou as colorful and exotic, it is an entertaining travel memoire as well.[14]

End of the Angkorian Period

The end of the Angkorian period is generally set at 1431 A.D., the year Angkor was sacked and looted by Thai invaders, though the civilization already had been in decline in the 13th and 14th centuries. In the course of the 15th century, nearly all of Angkor was abandoned, except for Angkor Wat, which remained a Buddhist shrine. Several theories have been advanced to account for the decline and abandonment of Angkor.

War with the Thai

It is widely believed that the abandonment of the Khmer capital occurred as a result of Siamese invasions. Ongoing wars with the Siamese were already sapping the strength of Angkor at the time of Zhou Daguan toward the end of the 13th century. In his memoirs, Zhou reported that the country had been completely devastated by such a war, in which the entire population had been obligated to participate.[15] After the collapse of Angkor in 1431, many persons, texts and institutions were taken to the Thai capital of Ayutthaya in the west, while others departed for the new center of Khmer society at Phnom Penh in the south.

Erosion of the state religion

Some scholars have connected the decline of Angkor with the conversion of Cambodia to Theravada Buddhism following the reign of Jayavarman VII, arguing that this religious transition eroded the Hindu conception of kingship that undergirded the Angkorian civilization.[16] According to Angkor scholar George Coedès, Theravada Buddhism's denial of the ultimate reality of the individual served to sap the vitality of the royal personality cult which had provided the inspiration for the grand monuments of Angkor.[17]

Neglect of public works

According to George Coedès, the weakening of Angkor's royal government by ongoing war and the erosion of the cult of the devaraja undermined the government's ability to engage in important public works, such as the construction and maintenance of the waterways essential for irrigation of the rice fields upon which Angkor's large population depended for its sustenance. As a result, Angkorian civilization suffered from a reduced economic base, and the population was forced to scatter.[18]

Natural disaster

Other scholars attempting to account for the rapid decline and abandonment of Angkor have hypothesized natural disasters such as earthquakes, inundations, or drastic climate changes as the relevant agents of destruction.[19] Recent research by Australian archaeologists suggests that the decline may have been due to a shortage of water caused by the transition from the medieval warm period to the little ice age.[20] Coedès rejects such meteorological hypotheses as unnecessary, and insists that the decline of Angkor is fully explained by the deleterious effects of war and the erosion of the state religion.[21]

Restoration and Preservation of Angkor

The great city and temples remained largely cloaked by the forest until the late 19th century when French archaeologists began a long restoration process. From 1907 to 1970 work was under the direction of the École française d'Extrême-Orient, which cleared away the forest, repaired foundations, and installed drains to protect the buildings from water damage. In addition, scholars associated with the school and including George Coedès, Maurice Glaize, Paul Mus, Philippe Stern and others initiated a program of historical scholarship and interpretation that is fundamental to the current understanding of Angkor.

Work resumed after the end of the Cambodia civil war, and since 1993 has been jointly co-ordinated by the French and Japanese and UNESCO through the International Co-ordinating Committee on the Safeguarding and Development of the Historic Site of Angkor (ICC), while Cambodian work is carried out by the Authority for the Protection and Management of Angkor and the Region of Siem Reap (APSARA), created in 1995. Some temples have been carefully taken apart stone by stone and reassembled on concrete foundations, in accordance with the method of anastylosis. World Monuments Fund has aided Preah Khan, the Churning of the Sea of Milk (a 49-meter-long bas-relief frieze in Angkor Wat), Ta Som, and Phnom Bakheng. International tourism to Angkor has increased significantly in recent years, with visitor numbers reaching 900,000 in 2006; this poses additional conservation problems but has also provided financial assistance to restoration.[22]

Religious History of Angkor

Historical Angkor was more than a site for religious art and architecture. It was the site of vast cities that responded to all the needs of a people, not only to specifically religious needs. Aside from a few old bridges, however, all of the remaining monuments are religious edifices. In Angkorian times, all non-religious buildings, including the residence of the king himself, were constructed of perishable materials, such as wood, "because only the gods had a right to residences made of stone."[23] Similarly, the vast majority of the surviving stone inscriptions are about the religious foundations of kings and other potentates.[24] As a result, it is easier to write the history of Angkorian state religion than it is to write that of just about any other aspect of Angkorian society.

Several religious movements contributed to the historical development of religion at Angkor:

- Indigenous religious cults, including those centered on worship of the ancestors and of the lingam;

- A royal personality cult, identifying the king with the deity, characteristic not only of Angkor, but of other Indic civilizations in southeast Asia, such as Champa and Java.

- Hinduism, especially Shaivism, the form of Hinduism focussed on the worship of Shiva and the lingam as the symbol of Shiva, but also Vaishnavism, the form of Hinduism focussed on the worship of Vishnu;

- Buddhism, in both its Mahayana and Theravada varieties.

Pre-Angkorian religion in Funan and Chenla

The religion of pre-Angkorian Cambodia, known to the Chinese as Funan (first century A.D. to ca. 550) and Chenla (ca. 550 - ca.800 A.D.), included elements of Hinduism, Buddhism and indigenous ancestor cults.[25]

Temples from the period of Chenla bear stone inscriptions, in both Sanskrit and Khmer, naming both Hindu and local ancestral deities, with Shiva supreme among the former.[26] The cult of Harihara was prominent; Buddhism was not, because, as reported by the Chinese pilgrim Yi Jing, a "wicked king" had destroyed it.[27] Characteristic of the religion of Chenla also was the cult of the lingam, or stone phallus that patronized and guaranteed fertility to the community in which it was located.[28]

Shiva and the Lingam in Angkorian state religion

The Khmer king Jayavarman II, whose assumption of power around 800 A.D. marks the beginning of the Angkorian period, established his capital at a place called Hariharalaya (today known as Roluos), at the northern end of the great lake, Tonle Sap.[29] Harihara is the name of a deity that combines the essence of Vishnu (Hari) with that of Shiva (Hara) and that was much favored by the Khmer kings.[30] Jayavarman II’s adoption of the epithet "devaraja" (god-king) signified the monarch's special connection with Shiva.[31]

The beginning of the Angkorian period was also marked by changes in religious architecture. During the reign of Jayavarman II, the single-chambered sanctuaries typical of Chenla gave way to temples constructed as a series of raised platforms bearing multiple towers.[32] Increasingly impressive temple pyramids came to represent Mount Meru, the home of the Hindu gods, with the moats surrounding the temples representing the mythological oceans.[33]

Typically, a lingam served as the central religious image of the Angkorian temple-mountain. The temple-mountain was the center of the city, and the lingam in the main sanctuary was the focus of the temple.[34] The name of the central lingam was the name of the king himself, combined with the suffix "-esvara" which designated Shiva.[35] Through the worship of the lingam, the king was identified with Shiva, and Shaivism became the state religion.[36] Thus, an inscription dated 881 A.D. indicates that king Indravarman I erected a lingam named "Indresvara."[37] Another inscription tells us that Indravarman erected eight lingams in his courts, and that they were named for the "eight elements of Shiva."[38] Similarly, Rajendravarman, whose reign began in 944 A.D., constructed the temple of Pre Rup, the central tower of which housed the royal lingam called "Rajendrabhadresvara."[39]

Vaishnavism in the dedication of Angkor Wat

In the early days of Angkor, the worship of Vishnu was secondary to that of Shiva. The relationship seems to have changed with the construction of Angkor Wat by King Suryavarman II as his personal mausoluem at the beginning of the 12th century A.D. The central religious image of Angkor Wat was an image of Vishnu, and an inscription identifies Suryavarman as "Paramavishnuloka," or "he who enters the heavenly world of Vishnu."[40] Religious syncretism, however, remained thoroughgoing in Khmer society: the state religion of Shaivism was not necessarily abrogated by Suryavarman's turn to Vishnu, and the temple may well have housed a royal lingam.[41] Furthermore, the turn to Vaishnavism did not abrogate the royal personality cult of Angkor by which the reigning king was identified with the deity. According to Angkor scholar George Coedès, "Angkor Wat is, if you like, a vaishnavite sanctuary, but the Vishnu venerated there was not the ancient Hindu deity nor even one of the deity's traditional incarnations, but the king Suryavarman II posthumously identified with Vishnu, consubstantial with him, residing in a mausoleum decorated with the graceful figures of apsaras just like Vishnu in his celestial palace."[42] Suryavarman proclaimed his identity with Vishnu, just as his predecessors had claimed consubstantiality with Shiva.

Mahayana Buddhism under Jayavarman VII

In the last quarter of the 12th century, King Jayavarman VII departed radically from the tradition of his predecessors when he adopted Mahayana Buddhism as his personal faith. Jayavarman also made Buddhism the state religion of his kingdom when he constructed the Buddhist temple known as the Bayon at the heart of his new capital city of Angkor Thom. In the famous face towers of the Bayon, the king represented himself as the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara moved by compassion for his subjects.[43] Thus, Jayavarman was able to perpetuate the royal personality cult of Angkor, while identifying the divine component of the cult with the bodhisattva rather than with Shiva.[44]

The Hindu Restoration

The Hindu restoration began around 1243 A.D., with the death of Jayavarman VII’s successor Indravarman II. The next king Jayavarman VIII was a Shaivite iconoclast who specialized in destroying Buddhist images and in reestablishing the Hindu shrines that his illustrious predecessor had converted to Buddhism. During the restoration, the Bayon was made a temple to Shiva, and its image of the Buddha was cast to the bottom of a well. Everywhere, cultic statues of the Buddha were replaced by lingams.[45]

Religious Pluralism in the era of Zhou Daguan

When Chinese traveller Zhou Daguan came to Angkor in A.D. 1296, he found what he took to be three separate religious groups. The dominant religion was that of Theravada Buddhism. Zhou observed that the monks had shaven heads and wore yellow robes.[46] The Buddhist temples impressed Zhou with their simplicity. He noted that the images of Buddha were made of gilded plaster.[47] The other two groups identified by Zhou appear to have been those of the Brahmans and of the Shaivites (lingam worshippers). About the Brahmans Zhou had little to say, except that they were often employed as high officials.[48] Of the Shaivites, whom he called "Taoists," Zhou wrote, "the only image which they revere is a block of stone analogous to the stone found in shrines of the god of the soil in China."[49]

The triumph of Theravada Buddhism

In the course of the 13th century, Theravada Buddhism coming from Siam (Thailand) made its appearance at Angkor. Gradually it became the dominant religion of Cambodia, displacing both Mahayana Buddhism and Shaivism.[50] The practice of Theravada Buddhism at Angkor continues until this day.

Archaeological Sites

The area of Angkor has many significant archaeological sites, including the following: Angkor Thom, Angkor Wat, Baksei Chamkrong, Banteay Kdei, Banteay Samré, Banteay Srei, Baphuon, the Bayon, Chau Say Tevoda, East Baray, East Mebon, Kbal Spean, the Khleangs, Krol Ko, Lolei, Neak Pean, Phimeanakas, Phnom Bakheng, Phnom Krom, Prasat Ak Yum, Prasat Kravan, Preah Khan, Preah Ko, Preah Palilay, Preah Pithu, Pre Rup, Spean Thma, Srah Srang, Ta Nei, Ta Prohm, Ta Som, Ta Keo, Terrace of the Elephants, Terrace of the Leper King, Thommanon, West Baray, West Mebon.

Terms and Phrases

- Angkor is a Khmer term meaning "city." It comes from the Sanskrit nagara.

- Banteay is a Khmer term meaning "citadel" or "fortress," which is also applied to walled temples.

- Baray means "reservoir."

- Esvara or Isvara is a suffix referring to the god Siva.

- Gopura is a Sanskrit term meaning "entrance pavilion" or "gateway."

- Jaya is a prefix meaning "victory."

- Phnom is a Khmer term meaning "hill."

- Prasat is a Khmer term meaning "tower." It comes from the Sanskrit prasada.

- Preah is a Khmer term meaning "sacred" or "holy." (Preah Khan means "sacred sword.")

- Srei is a Khmer term meaning "woman." (Banteay Srei means "citadel of women.")

- Ta is a Khmer term meaning "ancestor" or "grandfather." (Ta Prohm means "Ancestor Brahma." Neak ta means "ancestors" or "ancestral spirits.")

- Thom is a Khmer term meaning "big." (Angkor Thom means "big city.")

- Varman is a suffix meaning "shield" or "protector." (Suryavarman means "protected by Surya, the sun-god.")

- Wat is a Khmer term meaning (Buddhist) "temple." (Angkor Wat means "temple city.")

See also

References

Books and Articles

- Audric, John (1972). Angkor and the Khmer Empire. London: R. Hale. ISBN 0-7091-2945-9.

- Chandler, David (1992). A History of Cambodia. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Coedès, George (1968). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Honolulu: East West Center Press.

- Coedès, George (1943). Pour mieux comprendre Angkor. Hanoi: Imprimerie d'Extrême Orient.

- Freeman, Michael (1999). Ancient Angkor. Trumbull, Conn.: Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0426-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Higham, Charles (2001). The Civilization of Angkor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Stern, Philippe (1934). "Le temple-montagne khmèr, le culte du linga et le Devaraja," Bulletin de l'École française d’Extrême-Orient 34, pp. 611-616.

News Reports

- National Review: In Pol Pot Land: Ruins of varying types Sept 29, 2003.

- UNESCO: International Programme for the Preservation of Angkor Accessed 17 May 2005.

- "Climate change killed ancient city". The Australian. 2007-03-14. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- "Tourist invasion threatens to ruin glories of Angkor". The Observer. 2007-02-25.

- "Angkor engineered own end". The Australian. 2007-08-14. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|First=ignored (|first=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|Last=ignored (|last=suggested) (help) - "Map reveals ancient urban sprawl". BBC News. 2007-8-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Footnotes

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.4.

- ^ "Map reveals ancient urban sprawl," BBC News, 14 August 2007.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.53 ff.; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.34 ff.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.26; Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.4.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.63 ff.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.40.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.10.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.60; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.38 f.

- ^ "Map reveals ancient urban sprawl," BBC News, 14 August 2007.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.112 ff.; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.49.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.50 f.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.120 ff.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.116.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.134 ff.; Chandler, A History of Cambodia, pp.71 ff.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.32.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.78 ff.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, pp.64-65.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.30.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.30.

- ^ "Climate Change Killed Ancient City," The Australian.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.30.

- ^ "Tourist invasion threatens to ruin glories of Angkor," The Observer.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.18.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.2.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, pp.19-20.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.46.

- ^ Coedès, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, p.73f.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.20.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.57.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.20.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.34.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.57.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.9, 60.

- ^ Stern, "Le temple-montagne khmèr," p.615.

- ^ Stern, "Le temple-montagne khmèr," p.612.

- ^ Stern, "Le temple-montagne khmèr," p.616.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.63.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.63.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, pp.73ff.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.118.

- ^ Stern, "Le temple-montagne khmèr," p.616.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.63.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.121.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.62.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.133.

- ^ Higham, The Civilization of Angkor, p.137.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.72.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.72.

- ^ Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p.72.

- ^ Coedès, Pour mieux comprendre Angkor, p.19.

External links

- Template:Wikitravelpar

- Angkor Archaeological Park Map

- Siem Reap - The Gate to Angkor (Official Website of the Provincial Town Siem Reap on www.siemreap-town.gov.kh)

- Sacred Angkor

- Google Maps Map centered on Angkor Wat, with the Tonle Sap at the bottom.

- Greater Angkor Project International research project investigating the settlement context of the temples at Angkor

- www.theangkorguide.com Illustrated online guide to Angkor with plans and maps.

- Angkor Travel Guide Travel Guide with detailed temple descriptions, maps, photos, and background information.

- [1] High resolution NASA image

- Cambodia Cultural Profile (Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts/Visiting Arts)

- Khmer temples, maps and photos

- Angkor, the Khmer temples

- Photos and explanations of sites at Angkor with references to underlying stories from epics and sacred texts

- Destination in Cambodia - * Photos of Cambodia - * What's new? Cambodia Information from CambodiaTheLife.net

- Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, 1901-1936. Now online at gallica.bnf.fr, this journal documents cutting-edge early 20th century French scholarship on Angkor and other topics related to Asian civilizations.

- The World Monuments Fund in Angkor

- Angkor digital media archive - Photos, laser scans, panoramas of Angkor Wat and Banteay Kdei