Bonnethead

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2013) |

| Bonnethead shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Sphyrnidae |

| Genus: | Sphyrna |

| Species: | S. tiburo

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sphyrna tiburo | |

| |

| Range of the bonnethead shark | |

The bonnethead shark or shovelhead (Sphyrna tiburo) is a small member of the hammerhead shark genus Sphyrna, and part of the family Sphyrnidae. It is an abundant species on the American littoral, is the only shark species known to display sexual dimorphism in the morphology of the head, and is the only shark species known to be omnivorous.

Description

Characterized by a broad, smooth, spade-like head, it has the smallest cephalofoil (hammerhead) of all Sphyrna species. The body is grey-brown above and lighter on the underside. Typically, bonnethead sharks are about 2–3 ft (0.61–0.91 m) long, with a maximum size of about 5 ft (150 cm). Females tend to be larger than males.

The Greek word sphyrna translates as "hammer", referring to the shape of this shark's head; tiburo is the Taino word for shark.

-

Head, underside

-

Head, upper side

-

Upper teeth

-

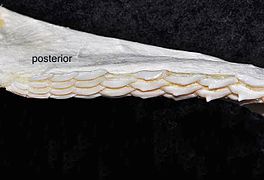

Upper teeth, posterior

-

Lower teeth

-

Lower teeth, posterior

Morphology

Sexual dimorphism

Bonnethead sharks are the only sharks known to exhibit sexual dimorphism in the morphology of the head. Adult females have a broadly rounded head, whereas males possess a distinct bulge along the anterior margin of the cephalofoil. This bulge is formed by the elongation of the rostral cartilages of the males at the onset of sexual maturity and corresponds temporally with the elongation of the clasper cartilages.[2]

Pectoral fins and swimming

The pectoral fins on most fish control pitching (up-and-down motion of the body), yawing (the side-to-side motion), and rolling. Most hammerhead sharks do not yaw or roll and achieve pitch using their cephalofoils. The smaller cephalofoil of a bonnethead shark is not as successful, so they have to rely on the combination of cephalofoils and their large pectoral fins for most of their motility. Compared to other hammerheads, bonnethead sharks have larger and more developed pectoral fins and are the only species of hammerhead to actively use pectoral fins for swimming.[citation needed]

Evolution

Using data from mtDNA analysis, scientist have found that evolution of hammerhead sharks probably began with a taxon that had a highly pronounced cephalofoil (most likely that similar to the winghead shark, Eusphyra blochii), and was later modified through selective pressures. Thus, judging by their smaller cephalofoils, bonnethead sharks are the more recent developments of a 25-million-year evolutionary process.[citation needed]

Distribution and habitat

This species occurs off the American coast, in regions where the water is usually warmer than 70 °F (21 °C). It ranges from New England, where it is rare, to the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil, and from southern California to Ecuador. During the summer, it is common in the inshore waters of the Carolinas and Georgia; in spring, summer, and fall, it is found off Florida and in the Gulf of Mexico. In the winter, the bonnethead shark is found closer to the equator, where the water is warmer.[citation needed]

It frequents shallow estuaries and bays over grass, mud, and sandy bottoms.[1]

Ecology

Behavior

The bonnethead shark is an active tropical shark that swims in small groups of five to 15 individuals, although schools of hundreds or even thousands have been reported. They move constantly following changes in water temperature and to maintain respiration. The bonnethead shark sinks if it does not keep moving, since hammerhead sharks are among the most negatively buoyant of marine vertebrates.

Diet

The shark feeds primarily on crustaceans, consisting mostly of blue crabs, but also shrimp, mollusks, and small fish. Its feeding behavior involves swimming across the seafloor, moving its head in arc patterns like a metal detector, looking for minute electromagnetic disturbances produced by crabs and other creatures hiding in the sediment. Upon discovery, it sharply turns around and bites into the sediment where the disturbance was detected. If a crab is caught, the bonnethead shark uses its teeth to grind its carapace and then uses suction to swallow.[citation needed] To accommodate the many types of animals on which it feeds, the bonnethead shark has small, sharp teeth in the front of the mouth (for grabbing soft prey) and flat, broad molars in the back (for crushing hard-shelled prey).

Bonnetheads also ingest large amounts of seagrass, which has been found to make up around 62.1% of gut content mass. The species appear to be omnivorous, the only known case of plant feeding in sharks.[3] A 2018 study with a carbon isotope-labelled seagrass diet found that they could digest seagrass with at least moderate efficiency, with 50±2% digestibility of seagrass organic matter, and had cellulose-component-degrading enzyme activity in their hindgut.[4][5]

Reproduction

The bonnethead shark is viviparous. Females reach sexual maturity at about 32 in, while males reach maturity around 24 in. Four to 12 pups are born in late summer and early fall, measuring 12 to 13 inches (300 to 330 mm).

Bonnetheads have one of the shortest gestation periods among sharks, lasting only 4.5–5.0 months.[1]

A bonnethead female produced a pup by parthenogenesis. The birth took place at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Nebraska; DNA analysis showed a perfect match between mother and pup.[6]

Conservation

The bonnethead is an abundant species and is currently classified as a least-concern species by the IUCN. It is heavily targeted by commercial and recreational fisheries, and constitutes up to 50% of all small shark landings in the Eastern US.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d "Sphyrna tiburo: Cortés, E., Lowry, D., Bethea, D. & Lowe, C.G". 2014. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T39387A2921446.en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kajiura, S. M.; Tyminski, J. P.; Forni, J. B.; Summers, A. P. (2005). "The sexually dimorphic cephalofoil of bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo". The Biological Bulletin. 209 (1): 1–5. doi:10.2307/3593136. JSTOR 3593136. PMID 16110088.

- ^ Hannah Lang (29 June 2017). "This Shark Eats Grass, and No One Knows Why". National Geographic.

- ^ Leigh, Samantha C.; Papastamatiou, Yannis P.; German, Donovan P. (2018). "Seagrass digestion by a notorious 'carnivore'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (1886): 20181583. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1583. ISSN 0962-8452.

- ^ Ian Sample (5 September 2018). "First known omnivorous shark species identified". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "Captive shark had 'virgin birth'". BBC News. 23 May 2007.

External links

- "Sphyrna tiburo". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Sphyrna tiburo". FishBase. October 2005 version.

- Species Description of Sphyrna tiburo at www.shark-references.com