Cosmic dust

Cosmic dust, also called extraterrestrial dust or space dust, is dust which exists in outer space, as well as all over the Earth.[1][2] Most cosmic dust particles are between a few molecules to 0.1 µm in size. Cosmic dust can be further distinguished by its astronomical location: intergalactic dust, interstellar dust, interplanetary dust (such as in the zodiacal cloud) and circumplanetary dust (such as in a planetary ring). In the Solar System, interplanetary dust causes the zodiacal light. Sources of Solar System dust include comet dust, asteroidal dust, dust from the Kuiper belt, and interstellar dust passing through the Solar System. The terminology has no specific application for describing materials found on the planet Earth except for dust that has demonstrably fallen to Earth. By one estimate, as much as 40,000 tons of cosmic dust reaches the Earth's surface every year,[3] with each grain having a mass between 10−16 kg (0.1 pg) and 10−4 kg (100 mg).[3] The density of the dust cloud through which the Earth is traveling is approximately 10−6/m3.[4] Cosmic dust also contains some complex organic compounds (amorphous organic solids with a mixed aromatic–aliphatic structure) that could be created naturally, and rapidly, by stars.[5][6][7] A smaller fraction of all dust in space consists of larger refractory minerals that condensed as matter left by stars. It is called "stardust" and is included in a separate section below.

Interstellar dust particles were collected by the Stardust spacecraft and samples were returned to Earth in 2006.[8][9][10][11]

Study and importance

Cosmic dust was once solely an annoyance to astronomers, as it obscures objects they wish to observe. When infrared astronomy began, the dust particles were observed to be significant and vital components of astrophysical processes. Their analysis can reveal information about phenomena like the formation of the Solar System.[13] For example, cosmic dust can drive the mass loss when a star is nearing the end of its life, play a part in the early stages of star formation, and form planets. In the Solar System, dust plays a major role in the zodiacal light, Saturn's B Ring spokes, the outer diffuse planetary rings at Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, and comets.

The study of dust is a largely researched topic that brings together different scientific fields: physics (solid-state, electromagnetic theory, surface physics, statistical physics, thermal physics), fractal mathematics, chemistry (chemical reactions on grain surfaces), meteoritics, as well as every branch of astronomy and astrophysics.[15] These disparate research areas can be linked by the following theme: the cosmic dust particles evolve cyclically; chemically, physically and dynamically. The evolution of dust traces out paths in which the Universe recycles material, in processes analogous to the daily recycling steps with which many people are familiar: production, storage, processing, collection, consumption, and discarding. Observations and measurements of cosmic dust in different regions provide an important insight into the Universe's recycling processes; in the clouds of the diffuse interstellar medium, in molecular clouds, in the circumstellar dust of young stellar objects, and in planetary systems such as the Solar System, where astronomers consider dust as in its most recycled state. The astronomers accumulate observational ‘snapshots’ of dust at different stages of its life and, over time, form a more complete movie of the Universe's complicated recycling steps.

Parameters such as the particle's initial motion, material properties, intervening plasma and magnetic field determined the dust particle's arrival at the dust detector. Slightly changing any of these parameters can give significantly different dust dynamical behavior. Therefore, one can learn about where that object came from, and what is (in) the intervening medium.

Detection methods

Cosmic dust can be detected by indirect methods that utilize the radiative properties of the cosmic dust particles.

Cosmic dust can also be detected directly ('in-situ') using a variety of collection methods and from a variety of collection locations. Estimates of the daily influx of extraterrestrial material entering the Earth's atmosphere range between 5 and 300 tonnes.[16][17]

NASA collects samples of star dust particles in the Earth's atmosphere using plate collectors under the wings of stratospheric-flying airplanes. Dust samples are also collected from surface deposits on the large Earth ice-masses (Antarctica and Greenland/the Arctic) and in deep-sea sediments.

Don Brownlee at the University of Washington in Seattle first reliably identified the extraterrestrial nature of collected dust particles in the latter 1970s. Another source is the meteorites, which contain stardust extracted from them. Stardust grains are solid refractory pieces of individual presolar stars. They are recognized by their extreme isotopic compositions, which can only be isotopic compositions within evolved stars, prior to any mixing with the interstellar medium. These grains condensed from the stellar matter as it cooled while leaving the star.

In interplanetary space, dust detectors on planetary spacecraft have been built and flown, some are presently flying, and more are presently being built to fly. The large orbital velocities of dust particles in interplanetary space (typically 10–40 km/s) make intact particle capture problematic. Instead, in-situ dust detectors are generally devised to measure parameters associated with the high-velocity impact of dust particles on the instrument, and then derive physical properties of the particles (usually mass and velocity) through laboratory calibration (i.e. impacting accelerated particles with known properties onto a laboratory replica of the dust detector). Over the years dust detectors have measured, among others, the impact light flash, acoustic signal and impact ionisation. Recently the dust instrument on Stardust captured particles intact in low-density aerogel.

Dust detectors in the past flew on the HEOS-2, Helios, Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Giotto, and Galileo space missions, on the Earth-orbiting LDEF, EURECA, and Gorid satellites, and some scientists have utilized the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft as giant Langmuir probes to directly sample the cosmic dust. Presently dust detectors are flying on the Ulysses, Cassini, Proba, Rosetta, Stardust, and the New Horizons spacecraft. The collected dust at Earth or collected further in space and returned by sample-return space missions is then analyzed by dust scientists in their respective laboratories all over the world. One large storage facility for cosmic dust exists at the NASA Houston JSC.

Infrared light can penetrate the cosmic dust clouds, allowing us to peer into regions of star formation and the centers of galaxies. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope is the largest infrared telescope ever launched into space. The Spitzer Space Telescope (formerly SIRTF, the Space Infrared Telescope Facility) was launched into space by a Delta rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida on 25 August 2003. During its mission, Spitzer will obtain images and spectra by detecting the infrared energy, or heat, radiated by objects in space between wavelengths of 3 and 180 micrometres. Most of this infrared radiation is blocked by the Earth's atmosphere and cannot be observed from the ground. The findings from the Spitzer already revitalized the studies of cosmic dust. A recent report from a Spitzer team shows some evidence that cosmic dust is formed near a supermassive black hole.[18]

Another detection mechanism is polarimetry. Dust grains are not spherical and tend to align to interstellar magnetic fields, preferentially polarising starlight that passes through dust clouds. In nearby interstellar space, where cosmic reddening is not sensitive enough to be detected, high precision optical polarimetry has been used to glean the structure of dust within the Local Bubble.[19]

Radiative properties

A dust particle interacts with electromagnetic radiation in a way that depends on its cross section, the wavelength of the electromagnetic radiation, and on the nature of the grain: its refractive index, size, etc. The radiation process for an individual grain is called its emissivity, dependent on the grain's efficiency factor. Furthermore, we have to specify whether the emissivity process is extinction, scattering, absorption, or polarisation. In the radiation emission curves, several important signatures identify the composition of the emitting or absorbing dust particles.

Dust particles can scatter light nonuniformly. Forward-scattered light means that light is redirected slightly by diffraction off its path from the star/sunlight, and back-scattered light is reflected light.

The scattering and extinction ("dimming") of the radiation gives useful information about the dust grain sizes. For example, if the object(s) in one's data is many times brighter in forward-scattered visible light than in back-scattered visible light, then we know that a significant fraction of the particles are about a micrometer in diameter.

The scattering of light from dust grains in long exposure visible photographs is quite noticeable in reflection nebulae, and gives clues about the individual particle's light-scattering properties. In X-ray wavelengths, many scientists are investigating the scattering of X-rays by interstellar dust, and some have suggested that astronomical X-ray sources would possess diffuse haloes, due to the dust.[21]

Stardust

Stardust grains (also called presolar grains by meteoriticists[22]) are contained within meteorites, from which they are extracted in terrestrial laboratories. Stardust was a component of the dust in the interstellar medium before its incorporation into meteorites. The meteorites have stored those stardust grains ever since the meteorites first assembled within the planetary accretion disk more than four billion years ago. So-called carbonaceous chondrites are especially fertile reservoirs of stardust. Each stardust grain existed before the Earth was formed. Stardust is a scientific term referring to refractory dust grains that condensed from cooling ejected gases from individual presolar stars and incorporated into the cloud from which the Solar System condensed.[23]

Many different types of stardust have been identified by laboratory measurements of the highly unusual isotopic composition of the chemical elements that comprise each stardust grain. These refractory mineral grains may earlier have been coated with volatile compounds, but those are lost in the dissolving of meteorite matter in acids, leaving only insoluble refractory minerals. Finding the grain cores without dissolving most of the meteorite has been possible, but difficult and labor-intensive (see presolar grains).

Many new aspects of nucleosynthesis have been discovered from the isotopic ratios within the stardust grains.[24] An important property of stardust is the hard, refractory, high-temperature nature of the grains. Prominent are silicon carbide, graphite, aluminium oxide, aluminium spinel, and other such solids that would condense at high temperature from a cooling gas, such as in stellar winds or in the decompression of the inside of a supernova. They differ greatly from the solids formed at low temperature within the interstellar medium.

Also important are their extreme isotopic compositions, which are expected to exist nowhere in the interstellar medium. This also suggests that the stardust condensed from the gases of individual stars before the isotopes could be diluted by mixing with the interstellar medium. These allow the source stars to be identified. For example, the heavy elements within the silicon carbide (SiC) grains are almost pure S-process isotopes, fitting their condensation within AGB star red giant winds inasmuch as the AGB stars are the main source of S-process nucleosynthesis and have atmospheres observed by astronomers to be highly enriched in dredged-up s process elements.

Another dramatic example is given by the so-called supernova condensates, usually shortened by acronym to SUNOCON (from SUperNOva CONdensate[25]) to distinguish them from other stardust condensed within stellar atmospheres. SUNOCONs contain in their calcium an excessively large abundance[26] of 44Ca, demonstrating that they condensed containing abundant radioactive 44Ti, which has a 65-year half-life. The outflowing 44Ti nuclei were thus still "alive" (radioactive) when the SUNOCON condensed near one year within the expanding supernova interior, but would have become an extinct radionuclide (specifically 44Ca) after the time required for mixing with the interstellar gas. Its discovery proved the prediction[27] from 1975 that it might be possible to identify SUNOCONs in this way. The SiC SUNOCONs (from supernovae) are only about 1% as numerous as are SiC stardust from AGB stars.

Stardust itself (SUNOCONs and AGB grains that come from specific stars) is but a modest fraction of the condensed cosmic dust, forming less than 0.1% of the mass of total interstellar solids. The high interest in stardust derives from new information that it has brought to the sciences of stellar evolution and nucleosynthesis.

Laboratories have studied solids that existed before the Earth was formed.[28] This was once thought impossible, especially in the 1970s when cosmochemists were confident that the Solar System began as a hot gas[29] virtually devoid of any remaining solids, which would have been vaporized by high temperature. The existence of stardust proved this historic picture incorrect.

Some bulk properties

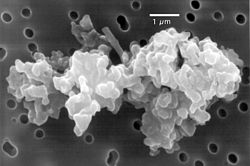

Cosmic dust is made of dust grains and aggregates of dust grains. These particles are irregularly shaped, with porosity ranging from fluffy to compact. The composition, size, and other properties depend on where the dust is found, and conversely, a compositional analysis of a dust particle can reveal much about the dust particle's origin. General diffuse interstellar medium dust, dust grains in dense clouds, planetary rings dust, and circumstellar dust, are each different in their characteristics. For example, grains in dense clouds have acquired a mantle of ice and on average are larger than dust particles in the diffuse interstellar medium. Interplanetary dust particles (IDPs) are generally larger still.

Most of the influx of extraterrestrial matter that falls onto the Earth is dominated by meteoroids with diameters in the range 50 to 500 micrometers, of average density 2.0 g/cm³ (with porosity about 40%). The total influx rate of meteoritic sities of most IDPs captured in the Earth's stratosphere range between 1 and 3 g/cm³, with an average density at about 2.0 g/cm³.[30]

Other specific dust properties:

- In circumstellar dust, astronomers have found molecular signatures of CO, silicon carbide, amorphous silicate, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, water ice, and polyformaldehyde, among others (in the diffuse interstellar medium, there is evidence for silicate and carbon grains).

- Cometary dust is generally different (with overlap) from asteroidal dust. Asteroidal dust resembles carbonaceous chondritic meteorites. Cometary dust resembles interstellar grains which can include silicates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and water ice.

Dust grain formation

The large grains in interstellar space are probably complex, with refractory cores that condensed within stellar outflows topped by layers acquired subsequently during incursions into cold dense interstellar clouds. That cyclic process of growth and destruction outside of the clouds has been modeled[31][32] to demonstrate that the cores live much longer than the average lifetime of dust mass. Those cores mostly start with silicate particles condensing in the atmospheres of cool oxygen rich red-giant stars and carbon grains condensing in the atmospheres of cool carbon stars. The red-giant stars have evolved off the main sequence and have entered the giant phase of their evolution and are the major source of refractory dust grain cores in galaxies. Those refractory cores are also called Stardust (section above), which is a scientific term for the small fraction of cosmic dust that condensed thermally within stellar gases as they were ejected from the stars. Several percent of refractory grain cores have condensed within expanding interiors of supernovae, a type of cosmic decompression chamber. And meteoriticists that study this refractory stardust extracted from meteorites often call it presolar grains, although the refractory stardust that they study is actually only a small fraction of all presolar dust. Stardust condenses within the stars via considerably different condensation chemistry than that of the bulk of cosmic dust, which accretes cold onto preexisting dust in dark molecular clouds of the galaxy. Those molecular clouds are very cold, typically less than 50K, so that ices of many kinds may accrete onto grains, perhaps to be destroyed later. Finally, when the Solar System formed, interstellar dust grains were further modified by chemical reactions within the planetary accretion disk. So the history of the complex grains in the early Solar System is complicated and only partially understood.

Astronomers know that the dust is formed in the envelopes of late-evolved stars from specific observational signatures. In infrared light, emission at 9.7 micrometres is a signature of silicate dust in cool evolved oxygen-rich giant stars. Emission at 11.5 micrometres indicates the presence of silicon carbide dust in cool evolved carbon-rich giant stars. These help provide evidence that the small silicate particles in space came from the ejected outer envelopes of these stars.[33][34]

Conditions in interstellar space are generally not suitable for the formation of silicate cores. This would take excessive time to accomplish, even if it might be possible. The arguments are that: given an observed typical grain diameter a, the time for a grain to attain a, and given the temperature of interstellar gas, it would take considerably longer than the age of the Universe for interstellar grains to form.[35] On the other hand, grains are seen to have recently formed in the vicinity of nearby stars, in nova and supernova ejecta, and in R Coronae Borealis variable stars which seem to eject discrete clouds containing both gas and dust. So mass loss from stars is unquestionably where the refractory cores of grains formed.

Most dust in the Solar System is highly processed dust, recycled from the material out of which the Solar System formed and subsequently collected in the planetesimals, and leftover solid material such as comets and asteroids, and reformed in each of those bodies' collisional lifetimes. During the Solar System's formation history, the most abundant element was (and still is) H2. The metallic elements: magnesium, silicon, and iron, which are the principal ingredients of rocky planets, condensed into solids at the highest temperatures of the planetary disk. Some molecules such as CO, N2, NH3, and free oxygen, existed in a gas phase. Some molecules, for example, graphite (C) and SiC would condense into solid grains in the planetary disk; but carbon and SiC grains found in meteorites are presolar based on their isotopic compositions, rather than from the planetary disk formation. Some molecules also formed complex organic compounds and some molecules formed frozen ice mantles, of which either could coat the "refractory" (Mg, Si, Fe) grain cores. Stardust once more provides an exception to the general trend, as it appears to be totally unprocessed since its thermal condensation within stars as refractory crystalline minerals. The condensation of graphite occurs within supernova interiors as they expand and cool, and do so even in gas containing more oxygen than carbon,[36] a surprising carbon chemistry made possible by the intense radioactive environment of supernovae. This special example of dust formation has merited specific review.[37]

Planetary disk formation of precursor molecules was determined, in large part, by the temperature of the solar nebula. Since the temperature of the solar nebula decreased with heliocentric distance, scientists can infer a dust grain's origin(s) with knowledge of the grain's materials. Some materials could only have been formed at high temperatures, while other grain materials could only have been formed at much lower temperatures. The materials in a single interplanetary dust particle often show that the grain elements formed in different locations and at different times in the solar nebula. Most of the matter present in the original solar nebula has since disappeared; drawn into the Sun, expelled into interstellar space, or reprocessed, for example, as part of the planets, asteroids or comets.

Due to their highly processed nature, IDPs (interplanetary dust particles) are fine-grained mixtures of thousands to millions of mineral grains and amorphous components. We can picture an IDP as a "matrix" of material with embedded elements which were formed at different times and places in the solar nebula and before the solar nebula's formation. Examples of embedded elements in cosmic dust are GEMS, chondrules, and CAIs.

From the solar nebula to Earth

The arrows in the adjacent diagram show one possible path from a collected interplanetary dust particle back to the early stages of the solar nebula.

We can follow the trail to the right in the diagram to the IDPs that contain the most volatile and primitive elements. The trail takes us first from interplanetary dust particles to chondritic interplanetary dust particles. Planetary scientists classify chondritic IDPs in terms of their diminishing degree of oxidation so that they fall into three major groups: the carbonaneous, the ordinary, and the enstatite chondrites. As the name implies, the carbonaceous chondrites are rich in carbon, and many have anomalies in the isotopic abundances of H, C, N, and O (Jessberger, 2000)[citation needed]. From the carbonaceous chondrites, we follow the trail to the most primitive materials. They are almost completely oxidized and contain the lowest condensation temperature elements ("volatile" elements) and the largest amount of organic compounds. Therefore, dust particles with these elements are thought to be formed in the early life of the Solar System. The volatile elements have never seen temperatures above about 500 K, therefore, the IDP grain "matrix" consists of some very primitive Solar System material. Such a scenario is true in the case of comet dust.[38] The provenance of the small fraction that is stardust (see above) is quite different; these refractory interstellar minerals thermally condense within stars, become a small component of interstellar matter, and therefore remain in the presolar planetary disk. Nuclear damage tracks are caused by the ion flux from solar flares. Solar wind ions impacting on the particle's surface produce amorphous radiation damaged rims on the particle's surface. And spallogenic nuclei are produced by galactic and solar cosmic rays. A dust particle that originates in the Kuiper Belt at 40 AU would have many more times the density of tracks, thicker amorphous rims and higher integrated doses than a dust particle originating in the main-asteroid belt.

Based on 2012 computer model studies, the complex organic molecules necessary for life may have formed in the protoplanetary disk of dust grains surrounding the Sun before the formation of the Earth.[39] According to the computer studies, this same process may also occur around other stars that acquire planets.[39] (Also see Extraterrestrial organic molecules.)

In September 2012, NASA scientists reported that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), subjected to interstellar medium (ISM) conditions, are transformed, through hydrogenation, oxygenation and hydroxylation, to more complex organics - "a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively".[40][41] Further, as a result of these transformations, the PAHs lose their spectroscopic signature which could be one of the reasons "for the lack of PAH detection in interstellar ice grains, particularly the outer regions of cold, dense clouds or the upper molecular layers of protoplanetary disks."[40][41]

In February 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database[42] for detecting and monitoring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe. According to NASA scientists, over 20% of the carbon in the Universe may be associated with PAHs, possible starting materials for the formation of life.[42] PAHs seem to have been formed shortly after the Big Bang, are abundant in the Universe,[43][44][45] and are associated with new stars and exoplanets.[42]

In March 2015, NASA scientists reported that, for the first time, complex DNA and RNA organic compounds of life, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, have been formed in the laboratory under outer space conditions, using starting chemicals, such as pyrimidine, found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the most carbon-rich chemical found in the Universe, may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar dust and gas clouds, according to the scientists.[46]

Some "dusty" clouds in the universe

The Solar System has its own interplanetary dust cloud, as do extrasolar systems. There are different types of nebulae with different physical causes and processes:

- Diffuse nebula

- Infrared (IR) reflection nebula

- Supernova remnant

- Molecular cloud

- HII regions

- Photodissociation regions

- Dark nebula

Distinctions between those types of nebula are that different radiation processes are at work. For example, H II regions, like the Orion Nebula, where a lot of star-formation is taking place, are characterized as thermal emission nebulae. Supernova remnants, on the other hand, like the Crab Nebula, are characterized as nonthermal emission (synchrotron radiation).

Some of the better known dusty regions in the Universe are the diffuse nebulae in the Messier catalog, for example: M1, M8, M16, M17, M20, M42, M43.[47]

Some larger dust catalogs are:

- Sharpless (1959) A Catalogue of HII Regions

- Lynds (1965) Catalogue of Bright Nebulae

- Lynds (1962) Catalogue of Dark Nebulae

- van den Bergh (1966) Catalogue of Reflection Nebulae

- Green (1988) Rev. Reference Cat. of Galactic SNRs

- The National Space Sciences Data Center (NSSDC)

- CDS Online Catalogs

Interstellar dust sample return

The Discovery program's Stardust mission, launched on 7 February 1999, returned samples to Earth on 15 January 2006. In the spring of 2014, the recovery of particles of interstellar dust from the samples was announced.[48]

See also

- Accretion

- Astrochemistry

- Atomic and molecular astrophysics

- Cosmochemistry

- Extraterrestrial materials

- Interstellar medium

- List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

- Micrometeoroid

- Tanpopo, a mission that collected cosmic dust in low Earth orbit

References

- ^ Broad, William J. (March 10, 2017). "Flecks of Extraterrestrial Dust, All Over the Roof". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ Gengel, M.J.; Larsen, J.; Van Ginneken, M.; Suttle, M.D. (December 1, 2016). "An urban collection of modern-day large micrometeorites: Evidence for variations in the extraterrestrial dust flux through the Quaternary" (PDF). Bibcode:2017Geo....45..119G. doi:10.1130/G38352.1. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Spacecraft Measurements of the Cosmic Dust Flux", Herbert A. Zook. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-8694-8_5

- ^ "Applications of the Electrodynamic Tether to Interstellar Travel" Gregory L. Matloff, Less Johnson, February, 2005

- ^ Chow, Denise (26 October 2011). "Discovery: Cosmic Dust Contains Organic Matter from Stars". Space.com. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ ScienceDaily Staff (26 October 2011). "Astronomers Discover Complex Organic Matter Exists Throughout the Universe". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Kwok, Sun; Zhang, Yong (26 October 2011). "Mixed aromatic–aliphatic organic nanoparticles as carriers of unidentified infrared emission features". Nature. 479 (7371): 80–3. Bibcode:2011Natur.479...80K. doi:10.1038/nature10542. PMID 22031328.

- ^ Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne; Jeffs, William (August 14, 2014). "Stardust Discovers Potential Interstellar Space Particles". NASA. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (August 14, 2014). "Specks returned from space may be alien visitors". AP News. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Hand, Eric (August 14, 2014). "Seven grains of interstellar dust reveal their secrets". Science News. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Westphal, Andrew J.; et al. (August 15, 2014). "Evidence for interstellar origin of seven dust particles collected by the Stardust spacecraft". Science. 345 (6198): 786–791. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..786W. doi:10.1126/science.1252496. PMID 25124433. Retrieved August 15, 2014.

- ^ "VLT Clears Up Dusty Mystery". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Starkey, Natalie (22 November 2013). "Your House is Full of Space Dust – It Reveals the Solar System's Story". Space.com. Retrieved 2014-02-16.

- ^ "Three Bands of Light". Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Eberhard Grün (2001). Interplanetary dust. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-42067-3.

- ^ Atkins, Nancy (March 2012), Getting a Handle on How Much Cosmic Dust Hits Earth, Universe Today

- ^ Royal Astronomical Society, press release (March 2012), CODITA: measuring the cosmic dust swept up by the Earth (UK-Germany National Astronomy Meeting NAM2012 ed.), Royal Astronomical Society, archived from the original on 2013-09-20

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Markwick-Kemper, F.; Gallagher, S. C.; Hines, D. C.; Bouwman, J. (2007). "Dust in the Wind: Crystalline Silicates, Corundum, and Periclase in PG 2112+059". Astrophysical Journal. 668 (2): L107–L110. arXiv:0710.2225. Bibcode:2007ApJ...668L.107M. doi:10.1086/523104.

- ^ Cotton, D. V.; et al. (January 2016). "The linear polarization of Southern bright stars measured at the parts-per-million level". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 455: 1607–1628. arXiv:1509.07221. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.455.1607C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2185.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) arXiv - ^ "A glowing jet from a young star". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

- ^ Smith RK; Edgar RJ; Shafer RA (Dec 2002). "The X-ray halo of GX 13+1". Astrophys. J. 581 (1): 562–69. arXiv:astro-ph/0204267. Bibcode:2002ApJ...581..562S. doi:10.1086/344151.

- ^ Zinner, E. (1998). "Stellar nucleosynthesis and the isotopic composition of premolar grains from primitive meteorites". Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 26: 147–188. Bibcode:1998AREPS..26..147Z. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.147.

- ^ Donald D. Clayton, Precondensed Matter: Key to the Early Solar System, Moon & Planets 19, 109 (1978)

- ^ D. D. Clayton; L. R. Nittler (2004). "Astrophysics with Presolar Stardust". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 42 (1): 39–78. Bibcode:2004ARA&A..42...39C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.42.053102.134022.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ D. D. Clayton, Moon and Planets 19, 109 (1978)

- ^ Nittler, L.R.; Amari, S.; Zinner, E.; Woosley, S.E. (1996). "Extinct 44Ti in Presolar Graphite and SiC: Proof of a Supernova Origin". Astrophys. J. 462: L31–34. Bibcode:1996ApJ...462L..31N. doi:10.1086/310021.

- ^ Clayton, Donald D. (1975). "22Na, Ne-E, Extinct radioactive anomalies and unsupported 40Ar". Nature. 257: 36–37. Bibcode:1975Natur.257...36C. doi:10.1038/257036b0.

- ^ Clayton, Donald D. (2000). "Planetary solids older than the Earth". Science. 288 (5466): 619. doi:10.1126/science.288.5466.617f.

- ^ Grossman, L. (1972). "Condensation in the primitive solar nebula". Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 36: 597–619. Bibcode:1972GeCoA..36..597G. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(72)90078-6.

- ^ Love S. G.; Joswiak D. J.; Brownlee D. E. (1992). "Densities of stratospheric micrometeorites". Icarus. 111 (1): 227–236. Bibcode:1994Icar..111..227L. doi:10.1006/icar.1994.1142.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Liffman, Kurt; Clayton, Donald D. (1988). "Stochastic histories of refractory interstellar dust". Proceeding of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 18: 637–57.

- ^ Liffman, Kurt; Clayton, Donald D. (1989). "Stochastic evolution of refractory interstellar dust during the chemical evolution of a two-phase interstellar medium". Astrophys. J. 340: 853–68. Bibcode:1989ApJ...340..853L. doi:10.1086/167440.

- ^ Humphreys, Roberta M.; Strecker, Donald W.; Ney, E. P. (1972). "Spectroscopic and Photometric Observations of M Supergiants in Carina". Astrophysical Journal. 172: 75. Bibcode:1972ApJ...172...75H. doi:10.1086/151329.

- ^ Evans 1994, pp. 164-167

- ^ Evans 1994, pp. 147-148

- ^ Clayton, Donald D.; Liu, W.; Dalgarno, A. (1999). "Condensation of carbon in radioactive supernova gas". Science. 283: 1290–92. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.1290C. doi:10.1126/science.283.5406.1290.

- ^ Clayton, Donald D. (2011). "A new astronomy with radioactivity: radiogenic carbon chemistry". New Astronomy Reviews. 55: 155–65. Bibcode:2011NewAR..55..155C. doi:10.1016/j.newar.2011.08.001.

- ^ Gruen, Eberhard (1999). Encyclopedia of the Solar System—Interplanetary Dust and the Zodiacal Cloud. pp. XX.

- ^ a b Moskowitz, Clara (29 March 2012). "Life's Building Blocks May Have Formed in Dust Around Young Sun". Space.com. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ a b Staff (September 20, 2012). "NASA Cooks Up Icy Organics to Mimic Life's Origins". Space.com. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Gudipati, Murthy S.; Yang, Rui (September 1, 2012). "In-Situ Probing Of Radiation-Induced Processing Of Organics In Astrophysical Ice Analogs—Novel Laser Desorption Laser Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectroscopic Studies". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 756 (1): L24. Bibcode:2012ApJ...756L..24G. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/756/1/L24. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c Hoover, Rachel (February 21, 2014). "Need to Track Organic Nano-Particles Across the Universe? NASA's Got an App for That". NASA. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (October 18, 2005). "Life's Building Blocks 'Abundant in Space'". Space.com. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Hudgins, Douglas M.; Bauschlicher, Jr., Charles W.; Allamandola, L. J. (October 10, 2005). "Variations in the Peak Position of the 6.2 μm Interstellar Emission Feature: A Tracer of N in the Interstellar Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Population". Astrophysical Journal. 632 (1): 316–332. Bibcode:2005ApJ...632..316H. doi:10.1086/432495. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- ^ Allamandola, Louis; et al. (April 13, 2011). "Cosmic Distribution of Chemical Complexity". NASA. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marlaire, Ruth (3 March 2015). "NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory". NASA. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Messier Catalog". Archived from the original on November 14, 1996. Retrieved 2005-07-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Stardust Interstellar Dust Particles". JSC, NASA. 2014-03-13.

Further reading

- Evans, Aneurin (1994). The Dusty Universe. Ellis Horwood.