Doping in figure skating

Doping in figure skating involves the use of illegal performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs), specifically those listed and monitored by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Figure skaters occasionally have positive doping results but it is not common.[1] Bans can be enforced on figure skaters by the International Skating Union (ISU) and each country's individual skating federation.[2][3] These bans can often be career ending due to the competitive nature of figure skating. A ban may be revoked if it can be proved that the skater tested positive for a prescribed medication. Some figure skaters will use PEDs to help with recovery time, allowing them to train harder and longer.[4] Figure skating is an aesthetic sport that combines both athleticism and artistic licence,[5] where weight-loss substances will have little effect on athletic performance but skaters may be perceived as more graceful and sleek, which is required for an athlete to be competitive.[5][6]

History

[edit]PEDs such as meldonium, pseudoephedrine and torasemide have been used in the sport of figure skating.[4] These drugs have little to do with building bulk muscle but can potentially be used to encourage a faster recovery, or diuretics may be used for weight loss. In terms of the technical complexity of figure skating, former American figure skater Scott Hamilton has stated that "It takes years to teach your body what it needs to do.[7] Instant strength will hinder those efforts, not aid them."[4] According to Dr. Franklin Nelson, chairman of the medical advisers to the International Skating Union (ISU): "Most drugs that are apparently used in other sports just are not effective in figure skating...where you change direction, change speeds, do lifts, jumps and spins", a viewpoint shared by many coaches in the figure skating community.[4] Figure skating requires lean figures from both men and women for both aesthetic and mechanical reasons, with an emphasis on achieving "a sleek, graceful bodily appearance while preserving the power, balance and flexibility a competitive athlete requires".[5] This could lead one to focus on weight loss, maintaining a low BMI, and a host of other medical issues such as developing an eating disorder.[5]

Though there is a long history of illegal PED use documented for swimming and cycling, it is much less common in figure skating. While PED use can drastically improve an individual's athletic performance in these particular sports due to the specific physical demands in these sports, the inherent complexity found in figure skating often discourages the use of illegal PEDs and the cost of being caught could be detrimental to their career.[4] Nelson, an experienced Olympic judge, states that in figure skating, ″Our rules are 15 months for a first offence and life for any subsequent offence,″ ″The sanctions are so extreme that they would effectively end a career″.[4] The nature of figure skater has one focused on their weight through controlling their diets to improve performance, opposed to using PEDs which could negatively impact their career due to the cost of being caught.[4][5]

Countries

[edit]Soviet Union and Russia

[edit]In a 1991 interview, three-time Olympic champion Irina Rodnina admitted that Soviet skaters used doping substances in preparation for the competitive season, stating: "Boys in pairs and singles used drugs, but this was only in August or September. This was done just in training, and everyone was tested (in the Soviet Union) before competitions."[8]

In 2000, Elena Berezhnaya, a pairs skater, tested positive for pseudoephedrine. She stated that she been taking cold medication approved by a doctor to treat bronchitis, but because she hadn't informed the ISU, was stripped of her 2000 European Championships gold medal.[9][10]

In 2008, Yuri Larionov, a pairs skater who won silver at the 2007 World Junior Championships and gold at the 2007–08 Junior Grand Prix Final with partner Vera Bazarova, was suspended for an anti-doping violation for 18 months (January 2008 to July 2009) for using furosemide, a powerful diuretic which the World Anti-Doping Agency classifies as a "masking" anabolic and steroids.[11][12] Larionov claimed that the use of the furosemide was for weight loss and not diuretic purposes.[13]

In 2016, former European ice dancing champion Ekaterina Bobrova failed a doping test when she tested positive for meldonium prior to the 2016 World Championships, after the substance had been banned by WADA.[14] Bobrova/Soloviev were not allowed to compete at the 2016 World Championships[15] However, her ban was overturned since there are was less than one microgram of meldonium and there were the uncertainties around how long it stays in the body. The ISU did not disqualify any of Bobrova/Soloviev's results.

In 2019, pair skater Alexandra Koshevaya was sanctioned for a two-year suspension (March 7, 2019 – March 6, 2021) after testing positive for torasemide during the 2019 Winter Universiade in Krasnoyarsk by the ISU.[16] She had mistakenly taken the medicine to reduce swelling (edema) in her foot and had not consulted a sports doctor about the ingestion of torasemide.[17] According to the ISU Disciplinary Commission the "Alleged Offender concluded by regretting what had happened and taking the obligation never to take any medicine without prior consultation with specialists again."[17]

In 2019, Anastasia Shakun, an ice dancer with Daniil Ragimov, received a one-year ban (November 10, 2018 – November 9, 2019) from the ISU after she claims she mistakenly took furosemide during competition for an eye problem.[18][19] She was "suspended from practices and participations in all competition",[18] and explained she had taken furosemide at the advice of pharmacy before the competition to deal with eye swelling and "forgotten that it was on the Prohibited List."[18]

Ladies' singles skater Maria Sotskova announced her retirement in July 2020. Over two months after her retirement, she received a 10-year disqualification from the sport by the Russian Anti-Doping Agency for forging a medical certificate to explain a doping violation; it was later reported that Sotskova was using the banned diuretic furosemide.[20] The Figure Skating Federation of Russia issued a verdict in March 2021 based on the RUSADA decision to disqualify Sotskova until April 5, 2030, backdating the start of her ban to April 2020.[21]

In 2022, ladies' singles skater Kamila Valieva was provisionally suspended by the Russian Anti-Doping Agency due to a positive test result for trimetazidine.[22] She was then unsuspended by RUSADA. This decision was appealed by the International Olympic Committee, World Anti-Doping Agency, and the International Testing Agency which was brought about to the Court of Arbitration for Sport. The hearing took place on February 13, 2022, and it was decided that Valieva would be able to participate in the 2022 Winter Olympics under many circumstances. However, on 29 January 2024, a full hearing of the case by the CAS resulted in her disqualification and suspension for four years from 25 December 2021 to 24 December 2025,[23] which, as of 22 March 2024, makes her and her teammates the only figure skaters to have an Olympic medal stripped for doping.

France

[edit]

Laurine Lecavelier is a single figure skater who tested positive in 2020 for cocaine at France's Master's de Patinage announced by the French Federation of Ice Sports.[24] Thus, there is a risk of a four-year suspension depending on whether it taken in or out of competition as if it was used for recreational purposes the penalty is less severe compared with the intention of performance enhancing.[25]

According to the ISU record, Christine Chiniard is a French ice dancer who was stripped of her third place medal at the 1983 World Junior Figure Skating Championships in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia, after failing a dope test for a weight-loss drug for prescribed medication. Thus dropping to fourth place at the World Junior Figure Skating Championships.

United States

[edit]In 2002 Kyoko Ina, a three-time Olympic pairs skater, was suspended for four years because she refused to take a random drug test at 10:30pm in July.[2] She was suspended by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) but not by the ISU as the test was an out of competition test.[26] There was confusion about her retirement from amateur competition as she announced she intended not to compete at the Olympics but provided no formal written notice to the USADA. Ina agreed to be suspended for two years without further appeal to the International Court of Arbitration for Sport.[27][2]

Kazakhstan

[edit]Darya Sirotina was banned for one year from January 17, 2017, to January 16, 2018, by skaters who was subject to a period of Ineligibility following an Anti-Doping Rule Violation by the ISU. The specific substance used is unknown.[3]

List of banned substances

[edit]There are four types of performance enhancing drugs in sport, this will include anabolic steroids, stimulants, human growth hormone and diuretics.[28] This section will have a greater focus on specific illegal PEDs that have been used by previous figure skaters.

Meldonium

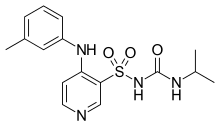

[edit]

Meldonium (mildronate; 3-(2,2,2-trimethylhydrazinium)propionate;) is a cardio-protective drug.[29] Under the WADA banned list of substances, meldonium is an S4 substance. It is typically a drug that helps improve circulation to the brain and been used for heart conditions such as angina.[30] This drug is produced in Latvia and most commonly used in northern Europe such as Eastern European Counties such as Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Azerbaijan, and Armenia and not currently approved by U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and in many countries of the European Union (EU).[30][7] As stated in this BBC article, "It is produced out of Latvia, has been around for some time and is commonly used in northern Europe.[30]

In figure skating, meldonium may have the potential to improve endurance performance and encourage the use of hormones and stimulants,[31][32] which could lead to misuse of meldonium as the sport requires strength, endurance and artistry.[7][5] Meldonium could be exploited because of the utilisation of fatty acid when exercising, along with decreased production of lactate acid after exercise and improved storage of glycogen.[31] This can benefit figure skaters (i.e. Elizaveta Tuktamysheva and Ekaterina Bobrova) as they have a faster recovery time and are able to train at least 33 hours a week (27hrs on-ice training and 6hrs off-ice training) meaning figure skaters are able to train even longer and harder and recover faster.[7][5] Illustrated by the potential effects for meldonium to improve performance in figure skating without building bulk from steroids.[4][7]

Pseudoephedrine

[edit]

Pseudoephedrine (PSE), is a commonly used drug for nasal decongestants that shrinks blood vessels in the nasal passage.[33][34] It is mainly used to treat nasal and sinus congestion or congestion of the tubes that drain fluid from your inner ears, called the eustachian tubes.[33] This drug has been banned by WADA as it is a stimulant and has the potential to enhance athletic performance[34] Due to its similarity between the structure of ephedrine and other central nervous systems stimulants.[34] In figure skating, as stated by Scott Hamilton that "stimulants were equally dangerous for a skater’s success. They could make you lose touch with the ice and ruin your concentration,″.[4] Thus illustrates the possible negative impact of stimulants in figure skating. But the effect of pseudoephedrine continues to be debated due to the lack of high quality random controlled trial (RCT) which could determine the exact role of pseudoephedrine in the body and whether it should be banned by WADA.[35] As stated by this study[35] that a "higher dose of PSE may be more beneficial than an inactive placebo or lower doses in enhancing athletic performances". With more research and understanding about the possible effects of this drugs, "Since PSE is present in over-the-counter decongestants such as Sudafed, changes may allow athletes(i.e Elena Berezhnaya) to take appropriate doses for symptomatic relief, while taking the necessary precautions to avoid doping allegations and harmful side effects".[35] This illustrates the potential that possible athletes could misuse the drug as it is a nasal decongestants without the intention of performance enhancing.

Torasemide

[edit]Torasemide is a high ceiling loop diuretic with the ability to promote excretion of water, sodium, and chloride.[36] If it used as a medication it is used to treat "fluid overload due to heart failure, kidney disease, and liver disease and high blood pressure." Torasemide is similar to furosemide (frusemide), but is twice as potent.[36] As a diuretic it aims to increase the rate of urine and sodium excretion in the body.[6] Though diuretics have no link with athletic performance, they can be used for one of two purposes.[6] Firstly, it has the ability to remove water from the body to meet the weight categories in certain sport events. Secondly, it can be used to mask the other doping agents by reducing the concentration of urine volume.[37] WADA states "the use of diuretics is banned both in competition and out of competition and diuretics are routinely screened for by anti-doping laboratories".[6] Weight and physical appearance are heavily emphasised in aesthetic sports such as figure skating, which could encourage the use of diuretics with the intention of weight loss to be competitive at an elite level.[6][38] Though there are many individuals who will use torasemide as a way to deal with swelling or weight loss shown in cases like Anastasia Shakun, Alexandra Koshevaia and Yuri Larionov, but many question the real effectiveness of using torasemide or furosemide and other diuretics on athletic performance.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2015 Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs) Report" (PDF). World Anti-Doping Agency. April 3, 2017. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c Rosewater, Amy (October 26, 2002). "PLUS: FIGURE SKATING; Ina Suspended For Not Taking Test". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Schmid, Fredi (June 29, 2017). "INTERNATIONAL SKATING UNION Communication No. 2105". ISU. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Skaters Untouched By Rising Tide of Drug-Related Sports". Associated Press News. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dwyer, Johanna; Eisenberg, Alanna; Prelack, Kathy; Song, Won; Sonneville, Kendrin; Ziegler, Paula (December 13, 2012). "Eating attitudes and food intakes of elite adolescent female figure skaters: A cross sectional study". Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 9 (1): 53. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-9-53. PMC 3529676. PMID 23237333.

- ^ a b c d e f Cadwallader, Amy B; de la Torre, Xavier; Tieri, Alessandra; Botrè, Francesco (September 2010). "The abuse of diuretics as performance-enhancing drugs and masking agents in sport doping: pharmacology, toxicology and analysis". British Journal of Pharmacology. 161 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00789.x. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 2962812. PMID 20718736.

- ^ a b c d e Lippi, Giuseppe; Mattiuzzi, Camilla (March 2017). "Misuse of the metabolic modulator meldonium in sports". Journal of Sport and Health Science. 6 (1): 49–51. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2016.06.008. ISSN 2095-2546. PMC 6188923. PMID 30356593.

- ^ Hersh, Phil (February 14, 1991). "Rodnina Confirms Soviet Steroid Use". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 7, 2018.

- ^ "7 Canadian figure skaters drug tested at Sochi 2014, since sport is so (not) notorious for doping". ca.sports.yahoo.com. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "ESPN.com - SKATING - Pairs champion fails drug test". ESPN. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Bazarova and Larionov: Surviving tough times". Golden Skate. July 4, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Перспективный российский фигурист сгонял вес при помощи запрещенных препаратов". NEWSru.com. February 12, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Yuri Larionov banned for two years | ArtOnIce". artonice.it. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Top Russian ice dancer Bobrova fails doping test - report". March 7, 2016. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ^ "Bobrova and Solovyov out of World Championships due to suspected doping violation". Reuters. March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2020.[dead link]

- ^ "Russian figure skater Koshevaya slapped with 2-year ban over doping abuse". TASS. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Disciplinary Commission".

- ^ a b c "Case No. 2019-01". ISU.

- ^ "Russian skater Shakun earns one-year doping ban after "mistakenly taking prohibited substance for eye complaint"". insidethegames.biz. April 9, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Мария Сотскова дисквалифицирована на 10 лет за подделку медицинской справки" [Maria Sotskova was disqualified for 10 years for forging a medical certificate] (in Russian). Rsport. September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Maria Sotskova, retired Russian figure skater, banned 10 years". NBC Sports. March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Beijing 2022: The ITA informs on figure skater Kamila Valieva". February 10, 2020.

- ^ "Kamila Valieva is found to have committed an anti-doping rule violation and sanctioned with a four-year period of ineligibility commencing on 25 december 2021" (PDF). Tas-cas.org. January 29, 2024. Retrieved January 29, 2024.

- ^ "Patinage artistique : Laurine Lecavelier dans la nasse - Pat. artistique - Dopage". L'Équipe (in French). Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ "Des précisions sur le contrôle positif de Laurine Lecavelier - Pat. artistique - Dopage". L'Équipe (in French). Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ "Kyoko Ina", Wikipedia, March 24, 2020, retrieved May 12, 2020

- ^ "Welcome to U.S. Figure Skating". August 19, 2004. Archived from the original on August 19, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ "Performance-enhancing drugs: Know the risks". mayoclinic.org. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Dambrova, Maija; Makrecka-Kuka, Marina; Vilskersts, Reinis; Makarova, Elina; Kuka, Janis; Liepinsh, Edgars (November 1, 2016). "Pharmacological effects of meldonium: Biochemical mechanisms and biomarkers of cardiometabolic activity". Pharmacological Research. Countries in focus: Pharmacology in the Baltic States. 113 (Pt B): 771–780. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.019. ISSN 1043-6618. PMID 26850121.

- ^ a b c "What is meldonium and how does it affect the body?". ABC News. March 8, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Belluz, Julia (March 8, 2016). "5 things to know about meldonium, the drug that brought Maria Sharapova down". Vox. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Mazanov, Jason. "Higher, faster ... cleaner? Doping and the Winter Olympics". The Conversation. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pseudoephedrine Uses, Dosage & Side Effects". Drugs.com. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c Gheorghiev, Maria D.; Hosseini, Farzad; Moran, Jason; Cooper, Chris E. (October 5, 2018). "Effects of pseudoephedrine on parameters affecting exercise performance: a meta-analysis". Sports Medicine - Open. 4 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s40798-018-0159-7. ISSN 2198-9761. PMC 6173670. PMID 30291523.

- ^ a b c Trinh, Kien V.; Kim, Jiin; Ritsma, Amanda (December 1, 2015). "Effect of pseudoephedrine in sport: a systematic review". BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 1 (1): e000066. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000066. ISSN 2055-7647. PMC 5117033. PMID 27900142.

- ^ a b Friedel, H. A.; Buckley, M. M. (January 1991). "Torasemide. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic potential". Drugs. 41 (1): 81–103. doi:10.2165/00003495-199141010-00008. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 1706990. S2CID 261404582.

- ^ "What is Prohibited". World Anti-Doping Agency. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ Davison, Kirsten Krahnstoever; Earnest, Mandy B.; Birch, Leann L. (April 2002). "Participation in Aesthetic Sports and Girls' Weight Concerns at Ages 5 and 7 Years". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 31 (3): 312–317. doi:10.1002/eat.10043. ISSN 0276-3478. PMC 2530926. PMID 11920993.