George Burns

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

George Burns | |

|---|---|

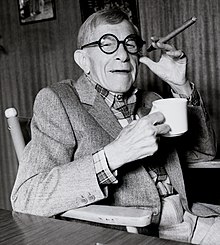

Burns in 1961 | |

| Born | Nathan Birnbaum January 20, 1896 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 9, 1996 (aged 100) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Nattie, Nate |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1902–1996 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Ronnie Burns |

George Burns (born Nathan Birnbaum; Template:Lang-yi; January 20, 1896 – March 9, 1996) was an American comedian, actor, singer, and writer. He was one of the few entertainers whose career successfully spanned vaudeville, radio, film, and television. His arched eyebrow and cigar-smoke punctuation became familiar trademarks for over three-quarters of a century. He and his wife, Gracie Allen, appeared on radio, television, and film as the comedy duo Burns and Allen.

At age 79, Burns had a sudden career revival as an amiable, beloved, and unusually active comedy elder statesman in the 1975 film The Sunshine Boys, for which he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. Burns, who became a centenarian in 1996, continued to work until just weeks before his death of cardiac arrest at his home in Beverly Hills.

Early life

George Burns was born Nathan Birnbaum on January 20, 1896 in New York City,[1] the ninth of 12 children born to Hadassah "Dorah" (née Bluth; 1857–1927) and Eliezer Birnbaum (1855–1903), known as Louis or Lippe, Jewish immigrants who had come to the United States from Kolbuszowa, Galicia, now Poland.[2] Burns was a member of the First Roumanian-American Congregation.[3]

His father was a substitute cantor at the local synagogue but usually worked as a coat presser. During the influenza epidemic of 1903, Lippe Birnbaum contracted the flu and died at the age of 47. Nattie (as George was then called) went to work to help support the family, shining shoes, running errands, and selling newspapers.[4]

When he landed a job as a syrup maker in a local candy shop at age seven, "Nate" as he was known, was "discovered", as he recalled long after:[5]

We were all about the same age, six and seven, and when we were bored making syrup, we used to practice singing harmony in the basement. One day our letter carrier came down to the basement. His name was Lou Farley. Feingold was his real name, but he changed it to Farley. He wanted the whole world to sing harmony. He came down to the basement once to deliver a letter and heard the four of us kids singing harmony. He liked our style, so we sang a couple more songs for him. Then we looked up at the head of the stairs and saw three or four people listening to us and smiling. In fact, they threw down a couple of pennies. So I said to the kids I was working with: no more chocolate syrup. It's show business from now on.

We called ourselves the Pee-Wee Quartet. We started out singing on ferryboats, in saloons, in brothels, and on street corners. We'd put our hats down for donations. Sometimes the customers threw something in the hats. Sometimes they took something out of the hats. Sometimes they took the hats.— George Burns

Burns started smoking cigars when he was 14.[6]

Burns was drafted into the United States Army when the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, but he failed the physical because he was extremely near-sighted.[citation needed] To try to hide his Jewish heritage, he adopted the stage name by which he would be known for the rest of his life. He claimed in a few interviews that the idea of the name originated from the fact that two star major league players (George H. Burns and George J. Burns, unrelated) were playing major league baseball at the time. Both men achieved over 2,000 major league hits and hold some major league records. Burns also was reported to have taken the name "George" from his brother Izzy (who hated his own name so he changed it to "George"), and the Burns from the Burns Brothers Coal Company (he used to steal coal from their truck).[7][8]: 33

He normally partnered with a girl, sometimes in an adagio dance routine, sometimes comic patter. Though he had an apparent flair for comedy, he never quite clicked with any of his partners, until he met a young Irish Catholic lady in 1923. "And all of a sudden," he said in later years, "the audience realized I had a talent. They were right. I did have a talent—and I was married to her for 38 years."[9]

His first wife was Hannah Siegel (stage name: Hermosa Jose), one of his dance partners. The marriage lasted twenty-six weeks and only occurred because her family would not let them go on tour unless they were married. They divorced at the end of the tour.[8]: 58

Burns' second wife and famous partner in their entertainment routines was Gracie Allen.[6]

Stage to screen

Burns and Allen got a start in motion pictures with a series of comic short films in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Their feature credits in the mid- to late-1930s included The Big Broadcast (1932); International House (1933), Six of a Kind (1934), (the latter two films with W.C. Fields), The Big Broadcast of 1936, The Big Broadcast of 1937, A Damsel in Distress (1937) in which they danced step-for-step with Fred Astaire, and College Swing (1938) with Bob Hope and Martha Raye. Honolulu would be Burns's last film for nearly 40 years.

Burns and Allen were indirectly responsible for the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby series of "Road" pictures. In 1938, William LeBaron, producer and managing director at Paramount, had a script prepared by Don Hartman and Frank Butler. It was to star Burns and Allen with Bing Crosby, who was then already an established star of radio, recordings and films. The story did not seem to fit the comedy team's style, so LeBaron ordered Hartman and Butler to rewrite the script to fit two male co-stars: Hope and Crosby. The script was titled Road to Singapore, and it made motion picture history when it was released in 1940.

Radio stars

Burns and Allen first made it to radio as the comedy relief for bandleader Guy Lombardo, which did not always sit well with Lombardo's home audience. In his later memoir, The Third Time Around, Burns revealed a college fraternity's protest letter, complaining that they resented their weekly dance parties with their girl friends listening to "Thirty Minutes of the Sweetest Music This Side of Heaven" had to be broken into by the droll vaudeville team.

In time, though, Burns and Allen found their own show and radio audience, first airing on February 15, 1932 and concentrating on their classic stage routines plus sketch comedy in which the Burns and Allen style was woven into different little scenes, not unlike the short films they made in Hollywood. They were also good for a clever publicity stunt, none more so than the hunt for Gracie's missing brother, a hunt that included Gracie turning up on other radio shows searching for him as well.

The couple was portrayed at first as younger singles, with Allen the object of both Burns' and other cast members' affections. Most notably, bandleaders Ray Noble (known for his phrase, "Gracie, this is the first time we've ever been alone") and Artie Shaw played "love" interests to Gracie. In addition, singer Tony Martin played an unwilling love interest of Gracie's, in which Gracie "sexually harassed" him, by threatening to fire him if the romantic interest was not reciprocated.

In time, however, due to slipping ratings and the difficulty of being portrayed as singles in light of the audience's close familiarity with their real-life marriage, the show adapted in the fall of 1941 to present them as the married couple they actually were. For a time, Burns and Allen had a rather distinguished and popular musical director: Artie Shaw, who also appeared as a character in some of the show's sketches. A somewhat different Gracie also marked this era, as the Gracie character could often be found to be mean to George.

George: Your mother cut my face out of the picture.

Gracie: Oh, George, you're being sensitive.

George: I am not! Look at my face! What happened to it?

Gracie: I don't know. It looks like you fell on it.

Or

Census Taker: What do you make?

Gracie: I make cookies and aprons and knit sweaters.

Census Taker: No, I mean what do you earn?

Gracie: George's salary.

As this format grew stale over the years, Burns and his fellow writers redeveloped the show as a situation comedy in the fall of 1941. The reformat focused on the couple's married life and life among various friends, including Elvia Allman as "Tootsie Sagwell," a man-hungry spinster in love with Bill Goodwin, and neighbors, until the characters of Harry and Blanche Morton entered the picture to stay.

Like The Jack Benny Program, the new George Burns & Gracie Allen Show portrayed George and Gracie as entertainers with their own weekly radio show. Goodwin remained, his character as "girl-crazy" as ever, and the music was now handled by Meredith Willson (later to be better known for composing the Broadway musical The Music Man). Willson also played himself on the show as a naive, friendly, girl-shy fellow. The new format's success made it one of the few classic radio comedies to completely re-invent itself and regain major fame.

Supporting players

The supporting cast during this phase included Mel Blanc as the melancholy, ironically named "Happy Postman" (his catchphrase was "Remember, keep smiling!"); Bea Benaderet (later Cousin Pearl in The Beverly Hillbillies, Kate Bradley in Petticoat Junction and the voice of Betty Rubble in The Flintstones) and Hal March (later more famous as the host of The $64,000 Question) as neighbors Blanche and Harry Morton; and the various members of Gracie's ladies' club, the Beverly Hills Uplift Society. One running gag during this period, stretching into the television era, was Burns' questionable singing voice, as Gracie lovingly referred to her husband as "Sugar Throat." The show received and maintained a Top 10 rating for the rest of its radio life.

New network

In the fall of 1949, after 12 years at NBC, the couple took the show back to its original network CBS, where they had risen to fame from 1932 to 1937. Their good friend Jack Benny reached a negotiating impasse with NBC over the corporation he set up ("Amusement Enterprises") to package his show, the better to put more of his earnings on a capital-gains basis and avoid the 80 percent taxes slapped on very high earners in the World War II period. When CBS executive William S. Paley convinced Benny to move to CBS (Paley, among other things, impressed Benny with his attitude that the performers make the network, not the other way around, as NBC chief David Sarnoff reputedly believed); Benny in turn convinced several NBC stars to join him, including Burns and Allen. Thus, CBS reaped the benefits when Burns and Allen moved to television in 1950.

Television

On television, The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show put faces to the radio characters audiences had come to love. A number of significant changes were seen in the show:

- A parade of actors portrayed Harry Morton: Hal March, The Life of Riley alumnus John Brown, veteran movie and television character actor Fred Clark, and future Mister Ed co-star Larry Keating.

- Burns often broke the fourth wall, and chatted with the home audience, telling understated jokes and commenting wryly about what show characters were doing or undoing. In later shows, he would actually turn on a television and watch what the other characters were up to when he was off-camera, then return to foil the plot.

- When announcer Bill Goodwin left after the first season, Burns hired announcer Harry Von Zell, a veteran of the Fred Allen and Eddie Cantor radio shows, to succeed him. Von Zell was cast as the good-natured, easily confused Burns and Allen announcer and buddy. He also became one of the show's running gags, when his involvement in Gracie's harebrained ideas would get him fired at least once a week by Burns.

- The first shows were simply a copy of the radio format, complete with lengthy and integrated commercials for sponsor Carnation Evaporated Milk by Goodwin. However, what worked well on radio appeared forced and plodding on television. The show was changed into the now-standard situation comedy format, with the commercials distinct from the plot.

- Midway through the run of the television show the Burns' two children, Sandra and Ronald, began to make appearances: Sandy in an occasional voice-over or brief on-air part (often as a telephone operator), and Ronnie in various small roles throughout the 4th and 5th seasons. Ronnie joined the regular cast in season 6. Typical of the blurred line between reality and fiction in the show, Ronnie played George and Gracie's on-air son, showing up in the second episode of season 6 ("Ronnie Arrives") with no explanation offered as to where he had been for the past five years of the show. Originally his character was an aspiring dramatic actor who held his parents' comedy style in befuddled contempt and deemed it unsuitable to the "serious" drama student. When the show's characters moved back to California in season 7 after spending the prior year in New York City, Ronnie's character dropped all apparent acting aspirations and instead enrolled in USC, becoming an inveterate girl chaser.

Burns and Allen also took a cue from Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz's Desilu Productions and formed a company of their own, McCadden Corporation (named after the street on which Burns' brother lived), headquartered on the General Service Studio lot in the heart of Hollywood, and set up to film television shows and commercials. Besides their own hit show (which made the transition from a bi-weekly live series to a weekly filmed version in the fall of 1952), the couple's company produced such television series as The Bob Cummings Show (subsequently syndicated and rerun as Love That Bob); The People's Choice, starring Jackie Cooper; Mona McCluskey, starring Juliet Prowse; and Mister Ed, starring Alan Young and a talented "talking" horse. Several of their good friend Jack Benny's 1953–55 filmed episodes were also produced by McCadden for CBS as well.

The George Burns Show

The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show ran on CBS Television from 1950 to 1958, when Burns at last consented to Allen's retirement. The onset of heart trouble in the early 1950s had left her exhausted from full-time work and she had been anxious to stop, but could not say "no" to Burns.

Burns attempted to continue the show (for new sponsor Colgate-Palmolive on NBC), but without Allen to provide the classic Gracie-isms, the show expired after a year.

Wendy and Me

Burns subsequently created Wendy and Me, a sitcom in which he co-starred with Connie Stevens, Ron Harper, and J. Pat O'Malley. He acted primarily as the narrator, and secondarily as the adviser to Stevens' Gracie-like character. The first episode involved the nearly 70-year-old Burns watching his younger neighbor's activities with amusement, just as he would watch the Burns and Allen television show while it was unfolding to get a jump on what Gracie was up to in its final two seasons. Again as in the Burns and Allen television show, George frequently broke the fourth wall by commenting directly to viewers. The series only lasted a year. In a promotion, Burns had joked that "Connie Stevens plays Wendy, and I play 'me'."

The Sunshine Boys

After Gracie's death, George immersed himself in work. McCadden Productions co-produced the television series No Time for Sergeants, based on the hit Broadway play; George also produced Juliet Prowse's 1965–66 NBC situation comedy, Mona McCluskey. At the same time, he toured the U.S. playing nightclub and theater engagements with such diverse partners as Carol Channing, Dorothy Provine, Jane Russell, Connie Haines, and Berle Davis. He also performed a series of solo concerts, playing university campuses, New York's Philharmonic Hall and winding up a successful season at Carnegie Hall, where he wowed a capacity audience with his show-stopping songs, dances, and jokes.

In 1974, Jack Benny signed to play one of the lead roles in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film version of Neil Simon's The Sunshine Boys (Red Skelton was originally the other, but he objected to some of the script's language). Benny's health had begun to fail, however, and he advised his manager Irving Fein to let longtime friend Burns fill in for him on a series of nightclub dates to which Benny had committed around the U.S.

Burns, who enjoyed working, accepted the job for what would be his first feature film appearance for 36 years. As he recalled years later:[5]

- "The happiest people I know are the ones that are still working. The saddest are the ones who are retired. Very few performers retire on their own. It's usually because no one wants them. Six years ago Sinatra announced his retirement. He's still working."—George Burns

Ill health had prevented Benny from working on The Sunshine Boys; he died of pancreatic cancer on December 26, 1974. Burns, heartbroken, said that the only time he ever wept in his life other than Gracie's death was when Benny died. He was chosen to give one of the eulogies at the funeral and said, "Jack was someone special to all of you, but he was so special to me...I cannot imagine my life without Jack Benny, and I will miss him so very much."[10] Burns then broke down and had to be helped to his seat. People who knew George said that he never could really come to terms with his beloved friend's death.

Six weeks before filming started, Burns had triple bypass surgery.[11]

Burns replaced Benny in the film as well as the club tour, a move that turned out to be one of the biggest breaks of his career; his wise performance as faded vaudevillian Al Lewis won him the 1975 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and permanently secured his career resurgence. At the age of 80, Burns was the oldest Oscar winner in the history of the Academy Awards, a record that would remain until Jessica Tandy won an Oscar for Driving Miss Daisy in 1989.

Oh, God!

In 1977, Burns made another hit film, Oh, God!, playing the omnipotent title role opposite singer John Denver as an earnest but befuddled supermarket manager, whom God picks at random to revive his message. The image of Burns in a sailor's cap and light springtime jacket as the droll Almighty influenced his subsequent comedic work, as well as that of other comedians. At a celebrity roast in his honor, Dean Martin adapted a Burns crack: "When George was growing up, the Top 10 were the Ten Commandments".

Burns appeared in this character along with Vanessa Williams on the September 1984 cover of Penthouse magazine, the issue which contained the notorious nude photos of Williams, as well as the first appearance of underage pornographic film star Traci Lords. A blurb on the cover even announced "Oh God, she's nude!"

Oh, God! inspired two sequels Oh, God! Book II (in which the Almighty engages a precocious schoolgirl played by Louanne Sirota to spread the word) and Oh, God! You Devil—in which Burns played a dual role as God and the devil, with the soul of a would-be songwriter (played by Ted Wass) at stake.

Later films

After guest-starring on The Muppet Show and Alice,[12] Burns appeared in 1978's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the film based on The Beatles' album of the same name. In 1979, at the age of 83, Burns starred in two feature films, Just You and Me, Kid and Going in Style. Burns remained active in films and TV past his 90th birthday. One of his last films was 1988's 18 Again!, based on his half-novelty, half-country music-based hit single, "I Wish I Was 18 Again". In this film, Burns played an 81-year-old self-made millionaire industrialist who switched bodies with his awkward, artistic, 18-year-old grandson (played by Charlie Schlatter).

Burns also did regular nightclub stand-up acts in his later years, usually portraying himself as a lecherous old man. He always smoked a cigar onstage and reputedly timed his monologues by the amount the cigar had burned down. For this reason, he preferred cheap El Producto cigars as the loosely wrapped tobacco burned longer. Burns once quipped "In my youth, they called me a rebel. When I was middle-aged, they called me eccentric. Now that I'm old, I'm doing the same thing I've always done and they're calling me senile."[citation needed]

Arthur Marx estimated that Burns smoked around 300,000 cigars during his lifetime, starting at the age of 14. In his final years, he smoked no more than four a day and he never used cigarettes or marijuana, claiming "Look, I can't get any more kicks than I'm getting. What can marijuana do for me that show business hasn't done?" His last feature film role was the cameo role of Milt Lackey, a 100-year-old stand-up comedian, in the 1994 comedy mystery Radioland Murders.

Final years and death

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Burns was still appearing at major hotel/casinos in Las Vegas, Reno, and Lake Tahoe during the early 1980s. When Burns turned 90 in 1986, the city of Los Angeles renamed the northern end of Hamel Road "George Burns Road."[13] City regulations prohibited naming a city street after a living person, but an exception was made for Burns.[citation needed] In celebration of Burns's 99th birthday in January 1995, Los Angeles renamed the eastern end of Alden Drive "Gracie Allen Drive." Burns was present at the unveiling ceremony (one of his last public appearances) where he quipped, "It's good to be here at the corner of Burns & Allen. At my age, it's good to be anywhere!"[13] George Burns Road and Gracie Allen Drive cross just a few blocks west of the Beverly Center mall in the heart of the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Burns remained in good health for most of his life, in part thanks to a daily exercise regimen of swimming, walks, sit-ups, and push-ups. He bought new Cadillacs every year and drove until the age of 93. After that, Burns had chauffeurs drive him around. In his later years, he also had difficulty reading fine print.

Burns suffered a head injury after falling in his bathtub in July 1994 and underwent surgery to remove fluid in his skull. Burns never fully recovered and his performing career came to an end. In February 1995, Burns, in what would be his final television appearance, was presented with the very first SAG Lifetime Achievement Award by the Screen Actors Guild. In December of that year, a month before his 100th birthday, Burns was well enough to attend a Christmas party hosted by Frank Sinatra (who turned 80 that month), where he reportedly caught the flu, which weakened him further. When Burns was 96, he had signed a lifetime contract with Caesars Palace in Las Vegas to perform stand-up comedy there, which included the guarantee of a show on his centenary, January 20, 1996. When that day actually came, however, he was too weak to deliver the planned performance. He released a statement joking how he would love for his 100th birthday to have "a night with Sharon Stone."

On March 9, 1996, 49 days after his centenary, Burns died in his Beverly Hills home.[14] His funeral was held three days later at the Wee Kirk o' the Heather church in Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery, Glendale.[14] As much as he looked forward to reaching the age of 100, Burns also stated, about a year before he died, that he also looked forward to death, saying that on the day he would die, he would be with Gracie again in Heaven. Upon being interred with Gracie, the crypt's marker was changed from, "Grace Allen Burns-Beloved Wife And Mother (1902–1964)" to "Gracie Allen (1902–1964) & George Burns (1896–1996)-Together Again". George had always said that he wanted Gracie to have top billing.

Legacy

George Burns has three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: a motion pictures star at 1639 Vine Street, a television star at 6510 Hollywood Boulevard, and a live performance star at 6672 Hollywood Boulevard. The first two stars were placed during the initial installations of 1960, while the third star ceremony was held in 1984,[15][16] in the new category of live performance, or live theatre, established that year.[17] Burns is also a member of the Television Hall of Fame, where he and Gracie Allen were both inducted in 1988.

He is the subject of Rupert Holmes' one-actor play Say Goodnight Gracie.

Bibliography

Burns was a bestselling author who wrote a total of 10 books:

- Burns, George; Hobart Lindsay, Cynthia (1955). I Love Her, That's Why: An Autobiography. Simon and Schuster.

- Burns, George (1976). Living It Up; or, They Still Love Me in Altoona!. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-11636-0.

- Burns, George (1980). The Third Time Around. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-12169-2.

- Burns, George (1983). How to Live to Be 100 – Or More: The Ultimate Diet, Sex and Exercise Book (At My Age, Sex Gets Second Billing). Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-12939-1.

- Burns, George (1984). Dr. Burns' Prescription for Happiness:* *Buy Two Books and Call Me in the Morning. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-12964-2.

- Burns, George (1985). Dear George: Advice and Answers from America's Leading Expert on Everything from A to B. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-13105-1.

- Burns, George (1988). Gracie: A Love Story. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-13384-8.

- Burns, George; Fisher, David (1989). All My Best Friends. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-13483-8.

- Burns, George; Goldman, Hal (1991). Wisdom of the 90's. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-13695-9.

- Burns, George (1996). 100 Years, 100 Stories. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-14179-9.

Filmography

- Features

- The Big Broadcast (1932) as Himself

- International House (1933) as Doctor Burns

- College Humor (1933) as Himself

- Six of a Kind (1934) as George Edward

- We're Not Dressing (1934) as Himself

- Many Happy Returns (1934) as Himself

- Love in Bloom (1935) as Himself

- Here Comes Cookie (1935) as Himself

- The Big Broadcast of 1936 (1935) as Himself

- The Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936) as Mr. Platt

- College Holiday (1936) as George Hymen

- Winterset (1936)

- A Damsel in Distress (1937) as Himself

- College Swing (1938) as George Jonas

- Honolulu (1939) as Joe Duffy

- The Solid Gold Cadillac (1956) as the Narrator (voice)

- The Sunshine Boys (1975) as Al Lewis

- Oh, God! (1977) as God

- Movie Movie (1978) as Himself – Introductory Segments (uncredited)

- Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978) as Mr. Kite

- Just You and Me, Kid (1979) as Bill

- Going in Style (1979) as Joe

- Oh, God! Book II (1980) as God

- Two of a Kind (1982) as Ross "Boppy" Minor

- Oh, God! You Devil (1984) as God / Harry O. Tophet

- 18 Again! (1988) as Jack Watson / David Watson

- A Century of Cinema (1994) (documentary)

- Radioland Murders (1994) as Milt Lackey (last film appearance)

- Short subjects

- Lambchops (1929) as George the Boyfriend

- Fit to Be Tied (1930) as a Tie Customer

- Pulling a Bone (1931) as a Man with a Bone

- The Antique Shop (1931) as Customer

- Once Over, Light (1931) as a Barbershop Customer

- 100% Service (1931) as George

- Oh, My Operation (1932) as the New Patient

- The Babbling Book (1932) as George

- Your Hat (1932) as a Hat Salesman

- Let's Dance (1933) as George, a Sailor

- Hollywood on Parade No. A-9 (1933) as Himself (uncredited)

- Walking the Baby (1933) as George

- Screen Snapshots: Famous Fathers and Sons (1946) as Himself

- Screen Snapshots: Hollywood Grows Up (1954)

- Screen Snapshots: Hollywood Beauty (1955) as Himself

- All About People (1967) as Narrator

- A Look at the World of Soylent Green (1973) as Himself

- The Lion Roars Again (1975) as Himself

Discography

Albums

| Year | Album | Chart positions | Label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Country | U.S. | |||

| 1973 | George Burns Sings | — | — | Buddah |

| 1980 | I Wish I Was Eighteen Again | 12 | 93 | Mercury |

| George Burns in Nashville | — | — | ||

| 1982 | Young at Heart | — | — | |

Singles

| Year | Single | Chart positions | Album | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Country | U.S. | CAN Country | CAN | CAN AC | |||

| 1980 | "I Wish I Was Eighteen Again" | 15 | 49 | 8 | 25 | 19 | I Wish I Was Eighteen Again |

| "The Arizona Whiz" | 85 | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1981 | "Willie, Won't You Sing a Song with Me" | 66 | — | — | — | — | George Burns in Nashville |

Soundtracks

Radio series

- The Robert Burns Panatella Show 1932–1933; CBS

- In their debut series, George and Gracie shared the bill with Guy Lombardo and his orchestra. The pair launched themselves into national stardom with their first major publicity stunt, Gracie's ongoing search for her missing brother.

- The White Owl Program 1933–1934; CBS

- The Adventures of Gracie 1934–1935; CBS

- The Campbell's Tomato Juice Program 1935–1937; CBS

- The Grape Nuts Program 1937–1938; NBC

- The Chesterfield Program 1938–1939; CBS

- The Hinds Honey and Almond Cream Program 1939–1940; CBS

- This series featured another wildly successful publicity stunt which had Gracie running for President of the United States.

- The Hormel Program 1940–1941; NBC

- Advertised a brand new product called Spam;[18] this show featured musical numbers by jazz great Artie Shaw.

- The Swan Soap Show 1941–1945; NBC, CBS

- This series featured a radical format change, in that George and Gracie played themselves as a married couple for the first time, and the show became a full-fledged domestic situation comedy. This was George's response to a marked drop in ratings under the old "Flirtation Act" format (as he later recalled, he finally realized "our jokes are too young for us").

- Maxwell House Coffee Time 1945–1949; NBC

- The Amm-i-Dent Toothpaste Show 1949–1950; CBS

TV series

- The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show 1950–1958; CBS

- Broadcast live every other week for the first two seasons, 26 episodes per year. Starting in the third season, all episodes were filmed and broadcast weekly, 40 episodes per year. A total of 291 episodes were created.

- The George Burns Show 1958–1959; NBC

- An unsuccessful attempt to continue the format of the Burns and Allen show without Gracie, the rest of the cast intact.

- Wendy and Me 1964–1965; ABC

- George plays narrator in this short-lived series, just as he had in the Burns and Allen show, but with far less on-screen time, as the focus is on a young couple played by Connie Stevens and Ron Harper. Stevens is, essentially, playing a version of Gracie's character.

- George Burns Comedy Week 1985; CBS

- Another short-lived series, a weekly comedy anthology program whose only connecting thread was George's presence as host. He does not appear in any of the actual storylines. He was 89 years old when the series was produced.

See also

References

- ^ Newcomb, Horace (2004). Encyclopedia of Television. Vol. 1, A–C (Second ed.). Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 369. ISBN 9781579583941.

- ^ Epstein, Lawrence J. (2011). George Burns: An American Life. McFarland & Company. p. 189. ISBN 9780786487936.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (January 24, 2006). "Downtown Congregation Vows to Repair Roof or Build Anew". The New York Times. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ http://articles.philly.com/1996-03-10/news/25635612_1_irving-fein-gracie-allen-show-george-burns

- ^ a b Marx, Arthur. "Ninety-eight-year-old George Burns Shares Memories of His Life". Cigar Aficionado. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

Comedian George Burns is not only a living legend, he's living proof that smoking between 10 and 15 cigars a day for 70 years contributes to one's longevity.

- ^ a b George Burns, Laughing All the Way

- ^ Lawrence J. Epstein (2011). George Burns: An American Life. McFarland. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7864-5849-3. OCLC 714086527.

- ^ a b Burns, George (November 1988). Gracie: A Love Story. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-13384-8.

'The one issue that never came up between Gracie and me was religion. Gracie was a practicing Irish Catholic. She tried to go to Mass every Sunday. I was Jewish, but I was out of practice. My religion was always treat other people nicely and be ready when they play your music. Mary Kelly, who was also Irish Catholic, wouldn't marry Jack Benny because she didn't want to marry out of her faith, but Gracie didn't seem to care. In fact, I was a lot more concerned about what my mother thought than I was about Gracie'.

- ^ Burns, George (1989). How to live to be 100—or more: the ultimate diet, sex, and exercise book. Penguin Group USA. p. 61.

- ^ "'Well!' Jack Would Have Said at the Turnout of the Stars". People. March 13, 1975. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ Natale, Richard (March 11, 1996). "George Burns: A Legend Laid To Rest". Daily Variety. p. 26.

- ^ Garlen, Jennifer C.; Graham, Anissa M. (2009). Kermit Culture: Critical Perspectives on Jim Henson's Muppets. McFarland & Company. p. 218. ISBN 978-0786442591.

- ^ a b "The Corner of Burns & Allen". Seeing-Stars.com. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Krebs, Albin (March 10, 1996). "George Burns, Straight Man And Ageless Wit, Dies at 100". The New York Times. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

He died at his home in Beverly Hills, Calif., said his manager, Irving Fein. ...

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame – George Burns". walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "George Burns – Hollywood Star Walk". Los Angeles Times. March 10, 1996. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Hollywood Walk of Fame – History". walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ^ "George Burns and Gracie Allen Spam Advertisement". Woman's Day. Gallery of Graphic Design. November 1, 1940. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

Further reading

- Gottfried, Martin (1996). George Burns. Simon & Schuster.

- Young, Jordan R. (1999). The Laugh Crafters: Comedy Writing in Radio & TV's Golden Age. Beverly Hills: Past Times Publishing. ISBN 0-940410-37-0.

- Burns, George (1989). All My Best Friends. G.B. Putnam's Sons

External links

- George Burns at IMDb

- George Burns at the Internet Broadway Database

- George Burns at AllMovie

- Home of George Burns & Gracie Allen-Radio Television Mirror-December 1940 (page 17)

- Georgeburns.com at the Wayback Machine (archived July 11, 2011)

- FBI Records: The Vault – George Burns at vault.fbi.gov

- 1896 births

- 1996 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American centenarians

- American male film actors

- American male radio actors

- American male television actors

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American people of Romanian-Jewish descent

- Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- Grammy Award winners

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish male comedians

- 20th-century American comedians

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Male actors from New York City

- People of Galician-Jewish descent

- Vaudeville performers

- Writers from New York City

- Jewish American comedians