Ghassanids

Ghassanids الغساسنة | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220–638 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Byzantine Empire | ||||||||

| Capital | Jabiyah | ||||||||

| Common languages | Old Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (official)[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 220–265 | Jafnah ibn Amr (first) | ||||||||

• 632–638 | Jabala ibn al-Ayham (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 220 | ||||||||

| 638 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

|

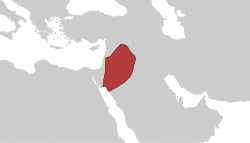

The Ghassanids,[a] also known as the Jafnids,[2] were an Arabian tribe. Originally from South Arabia, they migrated to the Levant in the 3rd century and established what would eventually become a Christian kingdom under the aegis of the Byzantine Empire,[3][4] as their society merged with local Chalcedonian Christianity and was largely Hellenized.[5] However, some of the Ghassanids may have already adhered to Christianity before they emigrated from South Arabia to escape religious persecution.[4][6]

As a Byzantine vassal, the Ghassanids participated in the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars, fighting against the Sasanian-allied Lakhmids, who were also an Arabian tribe, but adhered to the non-Chalcedonian Church of the East.[3][6] The territory of the Ghassanid kingdom also acted as an effective buffer zone, protecting Levantine lands that were the Byzantines had seized in the aftermath of raids by Bedouin tribes.[citation needed]

After just over 400 years of existence, the Ghassanid kingdom fell to the Rashidun Caliphate during the Muslim conquest of the Levant. A few of the tribe's members then converted to Islam, while most dispersed themselves amongst Melkites and Syriacs in what is now Jordan, Israel, Syria, Palestine, and Lebanon.[4]

Establishment

[edit]Genealogy and emigration from South Arabia

[edit]In the Arab genealogical tradition which developed during the early Islamic period, the Ghassanids were considered a branch of the Azd tribe of South Arabia/Yemen. In this genealogical scheme, their ancestor was Jafnah, a son of Amr Muzayqiya ibn Amir ibn Haritha ibn Imru’ al Qais ibn Tha’labah ibn Mazin ibn Azd, through whom the Ghassanids were purportedly linked with the Ansar (the Aws and Khazraj tribes of Medina), who were the descendants of Jafna's brother Tha'laba.[7] According to the historian Brian Ulrich, the links between Ghassan, the Ansar, and the wider Azd are historically tenuous, as these groups are almost always counted separately from each other in sources other than post-8th-century genealogical works and the story of the 'Scattering of Azd'.[8] In the latter story, the Azd migrate northward from Yemen and different groups of the tribe split off in different directions, with the Ghassan being one such group.[9]

Settlement in the Roman frontier

[edit]Per the "Scattering of Azd" story, the Ghassanids eventually settled within the Roman limes.[3][10] The tradition of Ghassanid migration finds support in the Geography of Ptolemy, which locates a tribe called the Kassanitai south of the Kinaidokolpitai and the river Baitios (probably the wadi Baysh). These are probably the people called Casani in Pliny the Elder, Gasandoi in Diodorus Siculus and Kasandreis in Photios I of Constantinople (relying on older sources).[11][12] The date of the migration to the Levant is unclear, but they are believed to have first arrived in the region of Syria between 250 and 300, with later waves of migration circa 400.[3] Their earliest appearance in records is dated to 473, when their chief, Amorkesos, signed a treaty with the Byzantine Empire acknowledging their status as foederati controlling parts of Palestine. He apparently became a Chalcedonian Christian at this time. By the year 510, the Ghassanids were no longer Miaphysites, but Chalcedonian.[13]

Byzantine period

[edit]The "Assanite Saracen" chief Podosaces that fought alongside the Sasanians during Julian's Persian expedition in 363 might have been a Ghassanid.[14]

After originally settling in the Levant, the Ghassanids became a client state to the Byzantine Empire. The Romans found a powerful ally in the Ghassanids who acted as a buffer zone against the Lakhmids. In addition, as kings of their own people, they were also phylarchs, native rulers of client frontier states.[15][16] The capital was at Jabiyah in the Golan Heights. Geographically, it occupied much of the eastern Levant, and its authority extended via tribal alliances with other Azdi tribes all the way to the northern Hijaz as far south as Yathrib (Medina).[17]

Byzantine–Sasanian Wars

[edit]The Ghassanids fought alongside the Byzantine Empire against the Persian Sasanians and Arab Lakhmids.[6] The lands of the Ghassanids also continually acted as a buffer zone, protecting Byzantine lands against raids by Bedouin tribes. Among their Arab allies were the Banu Judham and Banu Amilah.

The Byzantines were focused more on the East and a long war with the Sasanians was always their main concern. The Ghassanids maintained their rule as the guardian of trade routes, policed Lakhmid tribes and was a source of troops for the imperial army. The Ghassanid king al-Harith ibn Jabalah (reigned 529–569) supported the Byzantines against the Sasanians and was given in 529 by the emperor Justinian I, the highest imperial title that was ever bestowed upon a foreign ruler; also the status of patricians. In addition to that, al-Harith ibn Jabalah was given the rule over all the Arab allies of the Byzantine Empire.[18] Al-Harith was a Miaphysite Christian; he helped to revive the Syrian Miaphysite (Jacobite) Church and supported Miaphysite development despite Orthodox Byzantium regarding it as heretical. Later Byzantine mistrust and persecution of such religious unorthodoxy brought down his successors, Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith (reigned 569–582).

The Ghassanids, who had successfully opposed the Lakhmids of al-Hirah in Lower Mesopotamia, prospered economically and engaged in much religious and public building; they also patronized the arts and at one time entertained the Arab poets al-Nabighah and Hassan ibn Thabit at their courts.[3]

Early Islamic period

[edit]Rashidun conquest of the Levant

[edit]The nascent Muslim state in Medina, first under the Islamic prophet Muhammad (d. 632) and lastly under the second caliph, Umar (r. 634–644), made abortive attempts to contact or win over the Ghassan of Syria.[19] The last phylarch of the Ghassan, Jabala ibn al-Ayham, stories of whom are shrouded in legend, led his tribesmen and those of Byzantium's other allied Arab tribes in the Byzantine army that was routed by the Muslims at the Battle of Yarmouk in c. 636. After supposedly embracing Islam, Jabala left the faith and ultimately withdrew with his tribesmen from Syria to Byzantine-held Anatolia in 639, by which time the Muslims had conquered most of Byzantine Syria. Unable to make headway with the Ghassan, the Muslim administration in Syria under its governor Mu'awiya succeeded in allying with the Ghassan's old-established Syrian allies, the Banu Kalb. The latter became the cornerstone of Mu'awiya's military power in Syria, and later, when he became head of the Syria-based Umayyad Caliphate in 661, of the Islamic empire in general.[20]

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

[edit]Significant remnants of the Ghassan remained in Syria, residing in Damascus and the city's Ghouta countryside.[21] At least nominally and probably gradually, many of these Ghassanids embraced Islam, especially under Mu'awiya's rule. According to the historian Nancy Khalek, they consequently became an "indispensable" group of Muslim society in early Islamic Syria.[21] Mu'awiya actively sought the militarily and administratively experienced Syrian Christians, including the Ghassanids, and members of the tribe served him and later Umayyad caliphs as governors, commanders of the shurta (select troops), scribes, and chamberlains. Several descendants of the tribe's Tha'laba and Imru al-Qays branches are listed in the sources as Umayyad court poets, jurists, and officials in the eastern provinces of Khurasan, Adharbayjan and Armenia.[22]

When Mu'awiya's grandson, Caliph Mu'awiya II, died without a chosen successor amid the Second Muslim Civil War in 684, Umayyad rule was on the verge of collapse in Syria, having already collapsed throughout the caliphate, where the supporters of a rival caliph, the Mecca-based Ibn al-Zubayr, took charge. The Ghassan, along with their tribal allies in Syria, especially the Kalb, supported continued Umayyad rule to secure their interests under the dynasty, and nominated Mu'awiya's distant cousin, Marwan I, as caliph during a summit of the Syrian tribes in the old Ghassanid capital of Jabiyah.[23] Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri, the governor of Damascus, meanwhile, threw his backing behind Ibn al-Zubayr. During the Battle of Marj Rahit, which pitted Marwan against Dahhak in a meadow north of Damascus, the scion of the Ghassanid family in Damascus, Yazid ibn Abi al-Nims, led a revolt there and secured control of the city for Marwan, who routed Dahhak and assumed office. In a poem attributed to him, Marwan lauds the Ghassan, as well as the Kalb, Kinda, and Tanukh of Syria, for supporting him.[24]

The above tribes thereafter formed the Yaman faction, in opposition to the Qays tribes which backed Dahhak and Ibn al-Zubayr. The Qays–Yaman rivalry contributed to the downfall of Umayyad rule, with each faction supporting different Umayyad dynasts and governors in what became the Third Muslim Civil War. The Ghassanid Shabib ibn Abi Malik was a leader of the Yaman in Damascus and conspired to assassinate the pro-Qaysi Caliph al-Walid II (r. 743–744). After the latter was killed, the Ghassan marched on Damascus to help install his successor, the Yamani-backed Yazid III (r. 744–744).[25] The toppling of the Umayyads and the advent of the Iraq-based Abbasid Caliphate in 750 "was disastrous for the power, wealth and status of the Arab tribes in Syria", including the Ghassan, according to the historian Hugh N. Kennedy. By the 9th century, the tribe had adopted a settled life, being recorded by the geographer al-Ya'qubi (d. 890) to be living in the Ghouta gardens region of Damascus and in Gharandal in Transjordan.[26]

Scholarly families in Damascus

[edit]Two Damascene Ghassanid families in particular achieved prominence in early Islamic Syria, those of Yahya ibn Yahya al-Ghassani (d. 750s) and Abu Mushir al-Ghassani (d. 833). The former was the son of Caliph Marwan's head of the shurta, Yahya ibn Qays. Upon returning to Damascus after his stint as a governor of Mosul for the Umayyad caliph Umar II (r. 717–720), Yahya ibn Yahya took up scholarship and became known as the sayyid ahl Dimashq (leader of the people of Damascus), transmitting purported hadiths (traditions and utterances) of Muhammad, which he derived from his uncle Sulayman, who received the transmissions from Muhammad's Damascus-based companion, Abu Darda. Among some traditions sourced to Yahya ibn Yahya by later Muslim scholars are those regarding the discovery of John the Baptist's head in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus and others which praise the mosque's splendor and the Umayyad dynasty in general. Yahya ibn Yahya's sons, grandsons, great-grandsons and great-great-grandsons continued their ancestor's interests in hadith scholarship and remained part of the Damascene elite into the mid-9th century.[27]

Abu Mushir's grandfather, Abd al-A'la, was a hadith scholar and Abu Mushir studied under the famous Syrian scholar Sa'id ibn Abd al-Aziz al-Tanukhi. He became a prominent hadith scholar in Damascus, with special interest in the administrative history of Syria, its local elite's genealogies and local scholars.[28] During the Fourth Muslim Civil War between the Abbasid dynasts, an Umayyad, Abu al-Umaytir al-Sufyani, took power in Syria in 811, in a bid to reestablish the Umayyad Caliphate. Abu Mushir, whose grandfather was killed by the Abbasids in 750, disdained the Iraqis represented by the Abbasids and supported the restoration of Umayyad rule. He served as Abu al-Umaytir's qadi (chief jurist), but was imprisoned by the Abbasids in the years following the rebellion's suppression in 813.[29] His great-grandsons Abd al-Rabb ibn Muhammad and Amr ibn Abd al-A'la also attained fame as Damascene scholars.[28]

Kings

[edit]Medieval Arabic authors used the term Jafnids for the Ghassanids, a term modern scholars prefer at least for the ruling stratum of Ghassanid society.[2] Earlier kings are traditional, actual dates highly uncertain.

- Jafnah I ibn Amr (220–265)

- Amr I ibn Jafnah (265–270)

- Tha'labah ibn Amr (270–287) – Ally of Romans

- al-Harith I ibn Tha'labah (287–307)

- Jabalah I ibn al-Harith I (307–317)

- al-Harith II ibn Jabalah 'ibn Maria' (317–327)

- al-Mundhir I Senior ibn al-Harith II (327–330) with...

- al-Ayham ibn al-Harith II (327–330) and...

- al-Mundhir II Junior ibn al-Harith II (327–340) and...

- al-Nu'man I ibn al-Harith II (327–342) and...

- Amr II ibn al-Harith II (330–356) and...

- Jabalah II ibn al-Harith II (327–361)

- Jafnah II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–391) with...

- al-Nu'man II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–362)

- al-Nu'man III ibn Amr ibn al-Mundhir I (391–418)

- Jabalah III ibn al-Nu'man (418–434)

- al-Nu'man IV ibn al-Ayham (434–455) with...

- al-Harith III ibn al-Ayham (434–456) and...

- al-Nu'man V ibn al-Harith (434–453)

- al-Mundhir II ibn al-Nu'man (453–472) with...

- Amr III ibn al-Nu'man (453–486) and...

- Hijr ibn al-Nu'man (453–465)

- al-Harith IV ibn Hijr (486–512)

- Jabalah IV ibn al-Harith (512–529)

- al-Amr IV ibn Mah'shi (529)

- al-Harith V ibn Jabalah (529–569)

- al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith (569–581) with...

- Abu Kirab al-Nu'man ibn al-Harith (570–582)

- al-Nu'man VI ibn al-Mundhir (581–583)

- al-Harith VI ibn al-Harith (583)

- al-Nu'man VII ibn al-Harith Abu Kirab (583–?)

- al-Ayham ibn Jabalah (?–614)

- al-Mundhir IV ibn Jabalah (614–?)

- Sharahil ibn Jabalah (?–618)

- Amr IV ibn Jabalah (628)

- Jabalah V ibn al-Harith (628–632)

- Jabalah VI ibn al-Ayham (632–638)

Legacy

[edit]The Ghassanids reached their peak under al-Harith V and al-Mundhir III. Both were militarily successful allies of the Byzantines, especially against their enemies the Lakhmids, and secured Byzantium's southern flank and its political and commercial interests in Arabia proper. On the other hand, the Ghassanids remained fervently dedicated to Miaphysitism, which brought about their break with Byzantium and Mundhir's own downfall and exile, which was followed after 586 by the dissolution of the Ghassanid federation.[30] The Ghassanids' patronage of the Miaphysite Syrian Church was crucial for its survival and revival, and even its spread, through missionary activities, south into Arabia. According to the historian Warwick Ball, the Ghassanids' promotion of a simpler and more rigidly monotheistic form of Christianity in a specifically Arab context can be said to have anticipated Islam.[31] Ghassanid rule also brought a period of considerable prosperity for the Arabs on the eastern fringes of Syria, as evidenced by a spread of urbanization and the sponsorship of several churches, monasteries and other buildings. The surviving descriptions of the Ghassanid courts impart an image of luxury and an active cultural life, with patronage of the arts, music and especially Arab-language poetry. In the words of Ball, "the Ghassanid courts were the most important centres for Arabic poetry before the rise of the Caliphal courts under Islam", and their court culture, including their penchant for desert palaces like Qasr ibn Wardan, provided the model for the Umayyad caliphs and their court.[32]

After the fall of the first kingdom in the 7th century, several dynasties, both Christian and Muslim, ruled claiming to be a continuation of the House of Ghassan.[33] Besides the claim of the Phocid or Nikephorian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire being related. The Rasulid Sultans ruled from the 13th until the 15th century in Yemen,[34] while the Burji Mamluk Sultans did likewise in Egypt from the 14th to the 16th centuries.[35]

The last rulers to claim the titles of Royal Ghassanid successors were the Christian Sheikhs Al-Chemor in Mount Lebanon ruling the small sovereign principality of Akoura (from 1211 until 1641) and Zgharta-Zwaiya (from 1643 until 1747)[36] from Lebanon.[37][38][39]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Maalouf, Tony (2005). Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. p. 23. ISBN 9780825493638.

- ^ a b Fisher 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Hoberman, Barry (March–April 1983). "The King of Ghassan". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Bowersock, G. W.; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1998). Late Antiquity: A guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674511705.

Late Antiquity - Bowersock/Brown/Grabar.

- ^ "Deir Gassaneh".

- ^ a b c Bury, John (January 1958). History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian, Part 2. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486203997.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, p. 31.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume II (C-G): [Fasc. 23-40, 40a]". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. II (C-G): [Fasc. 23-40, 40a]. Brill. 28 May 1998. p. 1020. ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4.

- ^ Cuvigny & Robin 1996, pp. 704–706.

- ^ Bukharin 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Irfan Shahid, 1989, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century.

- ^ Fisher, Greg (2015). Arabs and Empires Before Islam. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 1, Irfan Shahîd, 1995, p. 103

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2 part 2, Irfan Shahîd, pg. 164

- ^ Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook, p. 160, at Google Books

- ^ Irfan Shahîd (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 2, part 1. pp. 51-104

- ^ Athamina 1994, p. 263.

- ^ Athamina 1994, pp. 263, 267–268.

- ^ a b Khalek 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Khalek 2011, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Crone 1980, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Khalek 2011, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Khalek 2011, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Madelung 2000, p. 333.

- ^ Ball 2000, pp. 102–103; Shahîd 1991, pp. 1020–1021.

- ^ Ball 2000, p. 105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- ^ Ball 2000, pp. 103–105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- ^ Late Antiquity - Bowesock/Brown/Grabar, Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 469

- ^ Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 332

- ^ Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 328

- ^ "Info". nna leb.

- ^ "El-Shark Lebanese Newspaper". Elsharkonline.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "مكتبة الشيخ ناصيف الشمر ! – النهار". Annahar.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "كفرحاتا بلدة شمالية متاخمة لزغرتا شفيعها مار ماما".

Bibliography

[edit]- Athamina, Khalil (1994). "The Appointment and Dismissal of Khālid b. al-Walīd from the Supreme Command: A Study of the Political Strategy of the Early Muslim Caliphs in Syria". Arabica. 41 (2): 253–272. doi:10.1163/157005894X00191. JSTOR 4057449.

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-02322-6.

- Bukharin, Mikhail D. (2009). "Towards the Earliest History of Kinda" (PDF). Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 20 (1): 64–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2008.00303.x.[dead link]

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Cuvigny, Hélène; Robin, Christian (1996). "Des Kinaidokolpites dans un ostracon grec du désert oriental (Égypte)". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 6 (2): 697–720.

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05327-8.

- Fisher, Greg (2018). "Jafnids". In Oliver Nicholson (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Vol. 2: J–Z. Oxford University Press. p. 804. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Fowden, Elizabeth Key (1999). The Barbarian Plain: Saint Sergius Between Rome and Iran. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21685-7.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2010). "Syrian Elites from Byzantium to Islam: Survival or Extinction?". In Haldon, John (ed.). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria: A Review of Current Debates. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 181–199. ISBN 9780754668497.

- Khalek, Nancy (2011). Damascus after the Muslim Conquest: Text and Image in Early Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973651-5.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2000). "Abūʾl-Amayṭar al-Sufyānī". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 24: 327–341.

- Millar, Fergus: "Rome's 'Arab' Allies in Late Antiquity". In: Henning Börm - Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.), Commutatio et Contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. Wellem Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, pp. 159–186.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1965). "Ghassān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 462–463. OCLC 495469475.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1991). "Ghassānids". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

- Ulrich, Brian (2019). Arabs in the Early Islamic Empire: Exploring al-Azd Tribal Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-3682-3.

- Ghassanids

- 220 establishments

- 638 disestablishments

- States and territories established in the 220s

- States and territories disestablished in the 7th century

- Christian groups in the Middle East

- Arab dynasties

- Tribes of Arabia

- Medieval Arabs

- Ancient Arab peoples

- Roman client kingdoms

- Roman buffer states

- Barbarian kingdoms

- Christian states