Great Northern War plague outbreak

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), many towns and areas around the Baltic Sea and East-Central Europe had a severe outbreak of the plague with a peak from 1708 to 1712. This epidemic was probably part of a pandemic affecting an area from Central Asia to the Mediterranean. Most probably via Constantinople, it spread to Pińczów in southern Poland, where it was first recorded in a Swedish military hospital in 1702. The plague then followed trade, travel and army routes, reached the Baltic coast at Prussia in 1709, affected areas all around the Baltic Sea by 1711 and reached Hamburg by 1712. Therefore, the course of the war and the course of the plague mutually affected each other: while soldiers and refugees were often agents of the plague, the death toll in the military as well as the depopulation of towns and rural areas sometimes severely impacted the ability to resist enemy forces or to supply troops.

This plague was the last to affect the area around the Baltic, which had experienced several waves of the plague since the Black Death of the 14th century. However, for some areas, it was the most severe. People died within a few days of first showing symptoms. Especially on the eastern coast from Prussia to Estonia, the average death toll for wide areas was up to two thirds or three quarters of the population, and many farms and villages were left completely desolated. It is, however, hard to distinguish between deaths due to a genuine plague infection and deaths due to starvation and other diseases that spread along with the plague. While buboes are recorded among the symptoms, contemporary means of diagnosis were poorly developed, and death records are often unspecific, incomplete or lost. Some towns and areas were affected only for one year, while in other places the plague recurred annually throughout several subsequent years. In some areas, a disproportionally high death toll is recorded for children and women, which may be due to famine and the men being drafted.

As the cause of the plague was unknown to contemporaries, with speculations reaching from religious causes over "bad air" to contaminated clothes, the only means of fighting the disease was containment, to separate the ill from the healthy. Cordons sanitaire were established around infected towns like Stralsund and Königsberg; one was also established around the whole Duchy of Prussia and another one between Scania and the Danish isles along the Sound, with Saltholm as the central quarantine station. "Plague houses" to quarantine infected people were established within or before the city walls. An example of the latter is the Charité of Berlin, which was spared from the plague.

Background

[edit]Local outbreaks of the plague are grouped into three plague pandemics, whereby the respective start and end dates and the assignment of some outbreaks to one or another pandemic are still subject to discussion.[1] According to Joseph P. Byrne from Belmont University, the pandemics were:

- the first plague pandemic from 541 to ~750, spreading from Egypt to the Mediterranean (starting with the Plague of Justinian) and northwestern Europe[2]

- the second plague pandemic from ~1345 to ~1840, spreading from Central Asia to the Mediterranean and Europe (starting with the Black Death), and probably also to China[2]

- the third plague pandemic from 1866 to the 1960s, spreading from China to various places around the world, notably the US-American west coast and India.[3]

However, the late medieval Black Death is sometimes seen not as the start of the second, but as the end of the first pandemic – in that case, the second pandemic's start would be 1361; the end dates of the second pandemic given in literature also vary, e.g. ~1890 instead of ~1840.[1]

The plague during the Great Northern War falls within the second pandemic, which by the late 17th century had its final recurrence in western Europe (e.g. the Great Plague of London 1666–68) and, in the 18th century final recurrences in the rest of Europe (e.g. the plague during the Great Northern War in the area around the Baltic sea, the Great Plague of Marseille 1720–22 in southern Europe, and the Russian plague of 1770–1772 in eastern Europe), being thereafter confined to less severe outbreaks in ports of the Ottoman Empire until the 1830s.[4]

In the late 17th century, the plague had retreated from Europe, making a last appearance in Northern Germany in 1682 and vanishing from the continent in 1684.[5] The subsequent wave hitting Europe during the Great Northern War most probably had its origins in Central Asia, spreading to Europe via Anatolia and Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire.[6] Georg Sticker numbered this epidemic as the "12th period" of plague epidemics, first recorded in Ahmedabad in 1683 and until 1724 affecting a territory from India over Persia, Asia Minor, the Levant and Egypt to Nubia and Ethiopia as well as to Morocco and southern France on the one hand and to East Central Europe up to Scandinavia on the other hand.[7] Constantinople was reached in 1685 and remained a site of infection for the subsequent years.[8] Sporadically, the plague had entered Poland–Lithuania since 1697, yet the wave of the plague that met and followed the armies of the Great Northern War was first recorded in Poland in 1702.[9]

Along with the plague, other diseases like dysentery, smallpox and spotted fever spread during the war, and at least in some regions the population encountered those while starving.[6] Already in 1695–1697, a great famine had already struck Finland (death toll between a quarter and a third of the population), Estonia (death toll about a fifth of the population), Livonia, and Lithuania[10] (where the famine as well as epidemics and warfare killed half of the population of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania between 1648 and 1697).[11] In addition, the winter of 1708-1709 was exceptionally long and severe;[12] as a result, the winter seed froze to death in Denmark and Prussia, and the soil had to be plowed and tilled again in the spring.[13]

1702–1706: Southern Poland

[edit]By 1702, the armies of Charles XII of Sweden had repelled and taken up pursuit of the armies of Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony, king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, defeating them in July at Klissow near Pińczów on the Nida in southern Poland.[14] In their military hospital in Pińczów, the Swedish army suffered its first plague infections of soldiers, recorded on the basis of reports from "trustworthy people from that very land" by Danzig (Gdańsk) physician Johann Christoph Gottwald.[15] In Poland, the plague recurred in various places until 1714.[9]

During the following two years, plague broke out in Ruthenia, Podolia and Volhynia, with Lviv (Lemberg, Lwów) suffering around 10,000 plague deaths in 1704 and 1705 (40% of all inhabitants).[6] From 1705 to 1706, occurrences of plague in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were also recorded in Kołomyję (Kolomyja, Kolomea), Stanisławów (Stanislaviv, Stanislau), Stryj (Stryi), Sambor (Sambir), Przemyśl, and Jarosław.[16]

Spread in Poland–Lithuania after 1706

[edit]After the Swedish incursion, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was in a state of civil war between the Warsaw Confederation, supportive of the pro-Swedish king Stanisław I Leszczyński, and the Sandomierz Confederation, supportive of Sweden's adversaries, i.e. the Russian tsar and August the Strong, who was forced to abdicate in 1706 by Charles XII.[citation needed]

In 1707,[9] the plague reached Kraków, where according to Frandsen (2009) 20,000 people died within three years,[6] according to Sticker (1905) 18,000 people within two years, most in 1707,[9] and according to Burchardt et al. (2009) 12,000 people between 1706 and 1709.[16] From Kraków, the plague spread to Lesser Poland (the surrounding area), Mazovia (including the city of Warsaw) and Great Poland with the cities of Ostrów, Kalisz (Kalisch) and Poznań (Posen).[16] In Warsaw, 30,000 people died in annually recurring plague epidemics between 1707 and 1710.[6] Poznań lost around 9,000 people,[17] about two thirds of its 14,000 inhabitants, to the plague between 1707 and 1709.[18] In 1708, the plague spread north to the war-torn town of Toruń (Thorn) in Royal Prussia, killing more than 4,000 people.[19]

When news of the plague in Poland arrived in the Kingdom of Prussia, then still neutral in the war,[20] precautions were taken to prevent it spreading across the border. From 1704, health certificates were compulsory for travellers from Poland.[21] From 1707, a broad cordon sanitaire extended around the border of the former Duchy of Prussia, and those crossing into the Prussian exclave were quarantined.[22] Yet the border was long and wooded, and not all roads could be guarded; thus bridges were demolished, lesser roads blocked, and orders were given to hang people avoiding the guarded crossings and burn or fumigate all incoming goods.[21] There were, however, many exemptions for people with cross-border estates or occupations, who were allowed to pass freely.[23]

Spread in the area around the Baltic sea 1708–1713

[edit]Prussia

[edit]

A few days after a Prussian official in Soldau forwarded the information that on 18 August 1708 the plague had reached the village of Piekielko on the Polish side of the border, the epidemic had crossed into the village of Bialutten on the Prussian side, killing most of its inhabitants within a month.[24] The Prussian authorities reacted by containing the village with a palisade; however, the survivors, led by the local reverend, had already taken refuge in the nearby woods.[25] On 13 September 1708, a Prussian official from Hohenstein reported that the plague had been brought to this small border town by the son of the local hatter returning from Polish service.[25] By December, 400 people had died in Hohenstein.[21] While the plague faded out during the hard winter, food became scarce due to war contributions and conscription, and the cordon sanitaire and the respective restrictions were lifted by edict on 12 July 1709.[21]

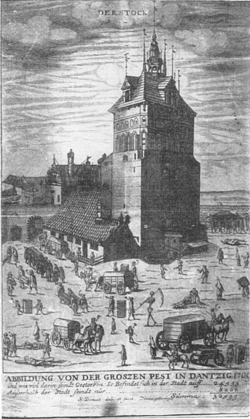

In January 1709, the plague reached Pillupönen (now Nevskoye in Kaliningrad Oblast) in the rural Prussian east,[26] and by the end of the winter it reached Danzig (Gdansk).[27] Danzig, at that time a largely autonomous, Protestant and German-speaking town in Polish Royal Prussia, had become one of the greatest towns in the area around the Baltic sea due to its position as a hub between Polish trade (via the Vistula) and international trade (via the Baltic Sea).[28] While it had so far avoided participation in the war, the conflict had affected it indirectly by a reduction of its trade volume, rising taxes[28] and food shortages.[29] The city council adopted a dual strategy of actively downplaying the plague to the outside world, especially Danzig's trading partners,[30] thus keeping the city open and allowing international and local trade to continue with few restrictions,[29] while at the same time the restrictions on burials were eased due to a coffin shortage and the deaths of many grave diggers, plague (pest) houses and new graveyards were designated,[31] and a "health commission" to organize the anti-plague measures was implemented to, for example, collect weekly reports from the physicians and provide the plague victims with food.[29] Until the end of May, it seemed that the plague would not be as severe, and the health commission's reports were openly accessible. However, the plague was not contained and spread from the plague houses to the poorer suburbs and surrounding countryside, and starting in early June the death toll rose significantly.[32] The health commission's reports were then declared secret.[29] When the plague faded out by December 1709[29] never to return to Danzig,[33] the town had lost about half of its inhabitants.[31]

The next large town to the east of Danzig was Königsberg in the Prussian kingdom, which had so far profited from the war by taking over some of the Swedish and Polish Livonian trade.[21] In preparation for the plague, a Collegium Sanitatis (health commission) was set up,[21] including physicians from the university and leading civilian and military officials of the town.[34] The plague arrived in August 1709, most probably carried by a Danzig sailor.[35] The provincial government was exiled to Wehlau while the chancellor, von Creytzen, remained in Königsberg and continued to work as the chairman of the Collegium Sanitatis, which met daily.[34] The city walls were manned by the military, the burghers were conscripted into neighborhood watches, medical and other personnel was hired, dressed in black waxed clothes and housed in separate buildings.[36] While at first the city authorities downplayed the plague, which had reached a peak in early October and then declined, this approach was abandoned when the death toll again started to rise significantly in November.[35] Without prior public announcement, a cordon sanitaire was implemented around the city, sealing it off completely from the surrounding countryside from 14/15 November until 21 December 1709.[36] When the plague had fully retreated from Königsberg by mid-1710, more than 9,500 townspeople had died,[37] about a quarter of its population.[38]

Located between Danzig and Königsberg, the town of Elbing (Elblag) became infected in late September 1709, probably by shoemakers travelling from Silesia.[39] Unusual compared to the plague in other places, the Elbing plague peaked in October 1709, faded out in the winter, peaked again in the spring 1710, faded in the summer, and peaked for a last time in the fall before vanishing in the winter, having killed about 1,200 people or 15% of the population each year.[39] This led Frandsen (2009) to speculate whether it was indeed the plague that raged in Elbing, a thorough analysis is however difficult due to the loss of the town's plague records in World War II.[39] On the other hand, some Elbing burghers profited from the plague in the neighboring cities insofar as its skippers were allowed to enter non-infected houses in Königsberg and, according to Frandsen (2009), "carried out an illegal, but probably very useful and lucrative trade between Königsberg and Danzig."[40] Elbing had protected its population by guarding its walls and enforcing a 40-day quarantine on incoming persons.[40]

However, East Prussia (the former Duchy of Prussia, since 1701 a province of the kingdom with the same name), where the plague had first occurred in late 1708 (see above) and returned from 1709 to 1711, lost more than 200,000[41] and up to 245,000 inhabitants,[42] which was more than a third of its population of ~600,000.[43] The peasants had been weakened by crop failures and pressured by high taxes: while 38.4% of king Frederick's subjects lived in eastern Prussia, the revenues gathered from this province accounted for only 16.4% of the kingdom's total tax income by the end of the 17th century, thereafter taxes for the peasants were increased by 65% from the outbreak of the war in 1700 until the outbreak of the plague in 1708.[42] When the hard winter of 1708/09 annilihated the winter seed, dysentery and hunger-typhus further weakened the population.[42] As a consequence, according to Kossert (2005), "the peasants were easy pray for the plague, as their physical condition was miserable,"[44] and 10,800 farms were completely deserted.[45] Especially hard-hit were regions with a substantial non-German population: Masuria in the south as well as the eastern counties with a substantial Lithuanian peasant population.[46] About 128,000 people died in the ämter (rural districts) of Insterburg, Memel, Ragnit and Tilsit,[42] and the number of villages populated completely by Lithuanians sank from 1,830 before the plague to 35 thereafter.[46] While indigenous, including Lithuanian population was included in the subsequent repopulation measures,[45] the ethnic make-up of the province changed[46] with the settlement of mostly German-speaking immigrants, most of whom were Protestants seeking refuge from religious prosecution (Exulanten).[47]

Brandenburg

[edit]In November 1709, when the Prussian king Frederick I returned to Berlin from a meeting with Russian tsar Peter the Great, the king had a strange encounter with his mentally deranged wife Sophia Louise, who in a white dress and with bloody hands pointed at him saying that the plague would devour the king of Babylon.[48] As there was a legend of a White Lady foretelling the deaths of the Hohenzollern, Frederick took his wife's outburst seriously[49] and ordered that precautions be taken for his residence city.[50] Among other measures, he ordered the construction of a pest house outside the city walls, the Berlin Charité.[50]

While the plague eventually spared Berlin,[51] it raged in the northeastern regions of Brandenburg, affecting the New March (Neumark) in 1710[52] and the Uckermark, where Prenzlau was infected on 3 August 1710.[53] There, the Prussian military enforced a quarantine and nailed up houses where infected people lived.[53] By January 1711, 665 people had died of the plague in Prenzlau and were buried on the city walls, and the quarantine was lifted on 10 August 1711.[53]

Pomerania

[edit]In August 1709, the plague arrived in the small Swedish Pomeranian town of (Alt-)Damm (now Dąbie) on the eastern bank of the Oder river, rapidly killing 500 inhabitants.[54] Stettin (now Szczecin), the capital city of Swedish Pomerania located on the opposite bank of the river, reacted by isolating the town with a guarded cordon sanitaire.[55] Precautions taken in Stettin since the arrival of the plague in Danzig included restrictions for travellers, especially soldiers' families returning from Swedish-occupied Poland after the lost Battle of Poltava (8 July 1709), and a ban on fruits in the town's markets, since fruits were believed to transmit the disease.[56] According to Zapnik (2006), the returning soldiers' wives who had contact with the plague-stricken areas around Poznań were most likely the transmitters of the plague to Pomerania.[57] After the outbreak in Damm, the mail route connecting Stettin with Stargard in the adjacent Prussian province of Pomerania via Damm was relocated to Podejuch.[55] Despite the precautions, the plague broke out in Warsow, just north of Stettin, and by the end of September also inside Stettin's walls, transmitted by a local woman who had provided food to her son in Damm.[55] As in Danzig (see above), the city council downplayed the plague cases to not impair Stettin's trade, but also set up a health commission and pest houses and hired personnel to deal with the infected.[55]

The situation was aggravated in October 1709, when the Swedish army corps commanded by the Swedish Pomeranian Ernst Detlev von Krassow entered Pomerania. Krassow's corps, together with units of the Polish king Stanislaw I, had failed to reinforce the army of king Charles XII of Sweden in Poltava as their eastward advance was blocked by Russian and Polish-Lithuanian forces near Lemberg (Lviv, Lwow).[58] When Charles was defeated at Poltava, many Polish-Lithuanian magnates switched from supporting Stanislaw I to supporting Augustus the Strong, and under pursuit by Russian and Saxon forces, Krassow's corps retreated westward through plague-stricken Poland, taking with them the abandoned Polish king as well as his court and wife.[55] Against the will of the Prussian king, whose troops were occupied in the War of the Spanish Succession, they crossed through the Prussian New March and Prussian Pomerania to reach Damm in Swedish Pomerania with the main army and the Swedish border near Wollin, Gollnow and Greifenhagen with smaller units on 21 October.[59] Krassow, who on his march was followed and monitored by Prussian officials, denied having infected soldiers in his corps when confronted with suspicions.[60] In a meeting with Prussian official Scheden, he justified his choice to march through infected Damm and probably infected Gollnow by responding that Gollnow was not infected at all, and that the situation in Damm would be dealt with by setting up a military corridor through the town separating the army from the inhabitants; Horn from Krassow's corps added reports that in Damm, after the death of 500 people, none of the remaining 400 inhabitants had died for three weeks.[61]

Contrary to Krassow's assurances, part of his corps was indeed infected with the plague, and the retreat from the infected Polish territories was carried out in disorder.[57] According to Zapnik (2006), "hordes of unrestrained soldateska, without adequate supplies and driven by fear of pursuit by their adversaries, behaved in a way more resembling their treatment of enemy territory when they had entered Swedish Pomerania."[57]

In addition to Damm, and Stettin, where 2,000 people died, the plague from 1709 to 1710 ravaged Pasewalk, killing 67% of its inhabitants, Anklam, and Kammin in Swedish Pomerania and Belgard in Prussian Pomerania.[54] From 1710 to 1711 the plague afflicted Stralsund, Altentreptow, Wolgast which lost 40% of its inhabitants, and Wollin, all in Swedish Pomerania,[54] as well as Stargard and Bahn in Prussian Pomerania and Prenzlau across the border with Brandenburg (all in 1710).[62] In 1711, the plague spread to Greifswald.[54]

Lithuania, Livonia, Estonia

[edit]

In the years 1710 and 1711, 190,000 People were infected half of which died.[41] The main Lithuanian city, Vilnius suffered from the plague from 1709 to 1713.[6] Between 23,000 and 33,700 people died in the city in 1709 and 1710; that number continued to rise in the following three years, when many of the starving from the Lithuanian countryside, which was ravaged by hunger and other diseases, took refuge within its walls.[6]

In Swedish Estonia and Swedish Livonia (both of which capitulated to the Russian tsar in 1710), the death toll between 1709 and 1711 was up to 75% of the population.[41] The largest city there was Riga, guarded by a garrison of 12,000, which after the Battle of Poltava was targeted by the forces of the Tsardom of Russia under Boris Sheremetev.[63] A siege was raised by November 1709; however, when the plague broke out in the city in May 1710, it soon spread from the defendants to the Russian siege forces, causing the latter to retreat behind a cordon sanitaire.[63] When the plague spread to Swedish Dünamünde upstream on the Düna (Daugava) river, thwarting Riga's defendants' hopes for relief, and plague and hunger became so widespread in the city[63] that only 1,500 men of the garrison were still alive,[64] on 5 (O.S.) / 15 July they surrendered the city to Sheremetev, who reported to the tsar 60,000 deaths in Riga and 10,000 deaths among his own forces.[63] While Frandsen (2009) dismisses the number for Riga as "most likely a heavy exaggeration"[63] and instead gives a rough estimate of 20,000 deaths by the end of the plague in October,[64] Sheremetev's number of Russian plague deaths seem to be "closer to the truth."[63] Dünamünde surrendered on 9 (O.S.) / 19 August, when only some officers and 64 healthy and ~500 sick ordinary soldiers were left.[63]

The contemporaries believed that the plague in Riga continued because, when the Russian forces lifted the siege, the influx of fresh air swirled and further distributed the plague's bad air throughout the city.[64] Some Russian measures, however, really contributed to the spread of the plague: Sheremetev allowed 114 Swedish government officials to leave for Dünamünde and from there for Stockholm with all their families and households, taking the plague with them;[64] also captured sick soldiers were sent to the isle of Ösel (Øsel, Saaremaa) off the Estonian coast, while the healthy were integrated into Sheremetev's corps.[63] Refugees from Dünamünde also carried the plague to Ösel, where the fortress of Arensburg was depopulated by the disease.[65]

The primary city of Swedish Estonia, Reval (Tallinn), was approached by a Russian force of 5,000 commanded by Christian Bauer in August 1710, and due to a decision by the local officials and nobles, capitulated on 30 September without actually being attacked.[66] Behind its walls was a population of ~20,000 people in August, composed of the regular inhabitants, soldiers, refugees and the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, which had been demolished by the defendants on 18 August.[67] By mid-December, about 15,000 of them had died of the plague, and the number of inhabitants was reduced to 1,990 inside the walls and 200 in the adjacent villages.[68] The rest had either fled elsewhere, or in the case of the surviving Swedish troops and some citizens, had been allowed to leave by ship after the surrender,[68] carrying the plague to Finland.[67]

Finland, Gotland and Central Sweden

[edit]

From Livonia and Estonia, refugees brought the plague to Central Sweden and Finland, at that time still an integral part of Sweden.[69] In June 1710, most probably via a ship from Pernau, the plague arrived in Stockholm, where the health commission (Collegium Medicum) until 29 August denied that it was indeed the plague, despite buboes being visible on the bodies of victims from the ship and in the town.[70] The plague raged in Stockholm until 1711, affecting primarily women (45.3% of the dead) and children (38.7% of the dead) in the poorer quarters outside the Old Town.[71] Of Stockholm's approximately 55,000 inhabitants, about 22,000 did not survive the plague.[72]

From Stockholm, the plague in August[73] and September 1710 spread to various other places in Uppland, including Uppsala and Enköping,[72] and to Södermanland.[73] The court was evacuated to Sala in August, the riksrådet to Arboga in September.[73] While in Uppland the disease seemingly faded out in the winter, it continued, though with less intensity, to ravage the Uppland countryside throughout the whole year of 1711, infecting for instance Värmdö, Tillinge and Danmark parish.[74] From Uppland, the plague spread southward. Jönköping lost 31% of its inhabitants in 1710 and 1711.[75] Besides "bad air" (miasma), animals were believed to transmit the disease, and people were forbidden to keep domestic animals inside the built-up areas and ordered to kill stray pigs.[75]

In September 1710, ships from Reval (Tallinn) carried the plague across the Gulf of Finland to Helsingfors (Helsinki), where it killed 1,185 inhabitants and refugees[76] (two thirds of the population),[77] and Borgå (Porvoo), where 652 people from in and around the town died.[76] Ekenäs (Tammisaari) and Åbo (Turku), then the largest town on the Finnish coast, with a population of 6,000, were also infected in September 1710.[76] 2,000 inhabitants and refugees died of the plague in Åbo by January 1711.[76] The plague then spread northwards and between 1710 and 1711 infected the towns of Nystad (Uusikaupunki), Raumo (Rauma), Björneborg (Pori), Nådendal (Naantali), Jakobstad (Pietarsaari), Gamlakarleby (Kokkola) and Uleåborg (Oulu) as well as an abundance of rural communities[76] up to a line between Uleåborg and Cajana (Kajana, Kajaani).[77] As the actual cause of the plague was unknown, counter-measures included flight, dissection of buboes and the lighting of huge fires to reduce the air's humidity, which was thought to reduce the chance of being affected by the plague's "bad air."[77]

The island of Gotland was also affected by the plague from 1710 to 1712.[78] In its port town of Visby, the plague claimed more than 450 deaths, which was about one fifth of its population.[78]

Zealand

[edit]Already in 1708, the Danish Politi- och Kommercekollegium proposed shielding the Danish islands with a marine cordon sanitaire, with dedicated ports for inspection of incoming ships from the Baltic Sea and a quarantine station on Saltholm, a small island in the Sound between Copenhagen on Zealand (Sjælland) and Malmö in Scania.[79] These measures were not implemented immediately, as the plague had not yet reached the Baltic coast.[79] On 16 and 19 August 1709, however, the king ordered the implementation of a revised plan, and a quarantine station was built on Saltholm for goods and crews of ships coming to Denmark from the infected ports of Danzig and Königsberg,[80] while their ships were meanwhile cleansed in Christianshavn; Dutch traders sailing from infected ports to the North Sea were to pay the Sound Dues on a special boat off the coast at Helsingør.[81] When the plague did not arrive in Denmark, though, Saltholm effectively fell out of use by 3 July 1710, when only three people were left in the station.[81] The main problem then was rather the lost Battle of Helsingborg and the aggressive type of typhus that the retreating Danish soldiers carried to Zealand from Scania.[82]

When in the course of the Russian conquest of Livonia refugees carried the plague to Finland and Central Sweden, and on the southern shore of the Baltic the plague had arrived in Stralsund, the worried council of Lübeck sent alerting letters to the Danish government, which after a discussion lasting from 21 October to 7/8 November resulted in a government decision to renew the quarantine requirement.[82] Saltholm was to be manned and equipped again, and the quarantine requirement was extended to ships from other infected ports.[82]

It is unclear whether at that time the plague had already arrived in Zealand's northeastern port of Helsingør (Elsinore), where the Sound Dues were collected from entering ships[83] and where a suspicious series of deaths was reported by the local health commission, allegedly starting with the death in the town on 1 October 1710 of a Dutch passenger arriving from Stockholm.[84] According to Persson (2001), it is "difficult to determine whether their cases have actually been a matter of plague, even if the progress in my eyes seems very suspicious;"[85] while Frandsen (2009) says that "I will risk my neck and postulate that the disease in Elsinore in the autumn of 1710 was not the plague but (as the barbers indicate) a form of typhus or spotted fever."[86]

There are however no doubts concerning the outbreak of the plague in late November 1710 in the small village of Lappen just north of Helsingør, populated by fishermen, ferrymen and nautical pilots.[85] The first death attributed to the plague was that of a fisherman's daughter on 14 November;[87] the peak of the plague in Lappen was reached already on 23 December, and while it faded out there in January 1711, it had already spread to or continued in neighboring Helsingør.[88] More than 1,800 people died in Helsingør in 1711, or roughly two thirds of its ~3,000 inhabitants.[89]

Despite the precautions, the plague ultimately spread from Helsingør to Copenhagen,[90] where from June to November 1711, between 12,000 and 23,000 people died out of a population of ~60,000.[91] Only on 19 September did the king decree that people from Zealand must not go to other Danish regions without a special passport; Zealand indeed remained the only Danish region with cases of the plague, except for Holstein (see below).[92]

Scania and Blekinge

[edit]In Scania (Skåne), the plague arrived on 20 (O.S.)/ 30 November 1710, when an infected Västanå boatman returned home from the navy.[93] Scania had not yet fully recovered from the Scanian War when its population was further weakened by a measles epidemic in 1706, a crop failure and the outbreak of smallpox in 1708–1709, an invasion of the Danish army in 1709, the expulsion of this army after the battle of Helsingborg, followed by conscriptions into the Swedish army and an outbreak of typhus in 1710.[93] While Scania was protected from an infection from the north by a cordon sanitaire between it and Småland, the plague came by sea[94] and made landfall not only in Västanå, but also in January 1711 in Domsten in Allerum parish, where the locals had ignored the ban on contact with their relatives and friends on the Danish side of the Sound, most notably in the infected area around Helsingør (Elsinore); the third starting point for the plague in Scania was Ystad, where on 19 June an infected soldier arrived from Swedish Pomerania.[93] The plague remained in Scania until 1713, probably 1714.[94]

In Blekinge, the plague arrived in August 1710 by means of army movements from and to Karlskrona, the central Swedish naval base.[73] By the beginning of 1712, about 15,000 soldiers and civilians had died not only in Karlskrona, but also in Karlshamn and other localities in Blekinge.[95]

Bremen, Bremen-Verden, Hamburg and Holstein

[edit]At the time of the Great Northern War, the northwest of the Holy Roman Empire was a patchwork with the Swedish dominion of Bremen-Verden located between the largely autonomous cities of Bremen and Hamburg, bordered to the south by the Electorate of Hanover, whose prince-elector George Louis became king of Great Britain in 1714, and to the north by the Duchy of Holstein, divided into Holstein-Glückstadt, ruled by the Danish king, and Holstein-Gottorp, whose duke Charles Frederick, a cousin and ally of Charles XII of Sweden, resided in Stockholm while Danish forces had occupied his share of the duchy only disturbed by Stenbock's march from Wakenstädt to Tønning in 1713.[96] Hamburg and Bremen were crowded with refugees of war, and Bremen in addition was suffering from a smallpox epidemic that had caused the deaths of 1,390 children in 1711.[97]

From Copenhagen,[98] the plague had infected several places in Holstein,[99] and while it is unclear whether Danish ships first brought it to Friedrichsort, Rendsburg or Laboe, and whether Schleswig and Flensburg were infected separately,[100] it is established that it was the Danish army that brought the plague to Holstein.[92] In addition to the ports, infected towns included Itzehoe, Altona, Kropp and Glückstadt,[101] in Kiel, the plague was limited to the castle and spared the town.[92] The plague also broke out in neighboring Bremen-Verden, whose capital, Stade, became infected[102] by early July 1712 and on 7 September capitulated to the Danish forces who had entered Bremen-Verden on 31 July.[97] The plague, as in formerly Swedish Livonia and Estonia, was a main reason for the defendants' surrender.[97]

In the spring and summer of 1712, the plague also broke out in Gröpelingen on Bremish territory.[97] The city council downplayed the plague cases in order not to impair trade, but set up a health commission and a pest house for quarantine measures.[97] Isolation of the infected did not prevent the plague from spreading into Bremen, but reduced the resulting deaths, which in 1712 were "only" 56 in Gröpelingen, which had a population of 360, and 12 in Bremen, which had a population of 28,000.[103] However, the plague returned to Bremen in 1713, killing another 180 people,[103]

Hamburg was hit much more severely. When the plague had reached Pinneberg and Rellingen just north of the Hamburg territory in the summer of 1712,[104] Hamburg restricted travel to the town, which the Danish king used as a pretext to encircle Hamburg with his forces[104] and confiscate Hamburg vessels on the River Elbe, demanding 500,000 thalers[105] (later reduced to 246,000 thalers)[106] to make up for this alleged discrimination against his subjects in Altona.[107] 12,000 Danish soldiers were moved before Hamburg's gates.[104] When the plague broke out in Hamburg less than three weeks later, it was carried there from the Danish troops by a prostitute from Hamburg's Gerkenshof lane, where out of 53 people 35 fell ill and 18 died.[108] The lane was blocked and isolated;[109] however, the quarantine could not prevent the disease from spreading through the densely built-up neighborhoods.[110] Among the dead was the plague doctor Majus, who belonged to those physicians who wore a beak-shaped mask containing a vinegar-soaked sponge to protect him against the miasma.[110] In December, the plague faded out.[109]

In January 1713, Stenbock's Swedish army marched through Hamburg and burned down the neighboring town of Altona,[111] which in contrast to Hamburg had refused to pay a contribution.[112] In Altona, the plague had killed 1,000 people, among them 300 Jews, while Hamburg remained free of the plague until July and did not take in refugees from Altona.[113] Just a week after the Swedish army had marched through Hamburg, the Russian army led by Peter the Great entered the town.[112] According to Frandsen (2009), the tsar "frolicked in Hamburg while his troops plundered the suburbs."[112]

When in August 1713 the plague broke out again,[112] it was much more severe than what Hamburg's inhabitants had experienced in 1712,[111] and the meanwhile returned Danish army established a cordon sanitaire around the city.[114] The cordon was supervised by Major von Ingversleben, who had dealt with the plague in Helsingør, and effectively prevented the plague from spreading to Holstein again.[112] When the plague finally faded out in Hamburg in March 1714, ~10,000 people had died of the disease.[112]

Death statistics by region

[edit]| Town/Area | Plague years | Peak | Inhabitants | Deaths (absolute) | Deaths (relative) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danzig (Gdańsk) | March 1709 – December 1709 | August 1709 – September 1709 | ~50,000 | 24,533 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[27] | |

| 1709 | ~50,000 | 50–65% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Danzig incl. surrounding places | 32,599 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[27] | ||||

| Vilnius | 1709–1713 | 1709–1710 | 23,000–33,700 (1709–10) | Frandsen (2009)[6] | ||

| Königsberg | August 1709 – mid-1710 | October 1709 – December 1709 | 35,000–40,000 | >9,500 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[37] | |

| 1709 | ~35,000 | 20–25% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Stettin | fall 1709–1711 | 11,000–12,000 | 1,650–2,200 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[115] | ||

| 1710 | ~11,000 | 15–20% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Memel (Klaipėda) | September 1709 – 1710 | 1710 | 1,401 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[116] | ||

| Tilsit | 1710 | June 1710 – October 1710 | 1,883 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[117] | ||

| Stargard | 1710–1711 | ~7,000 | 200–380 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[118] | ||

| 1710 | ~7,000 | 3–5% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Narva | June 1710 – late 1711 | ~3,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[119] | |||

| Riga | May 1710 – late 1711 | 10,455 | 6,300–7,350 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[120] | ||

| 1710 | ~10,500 | 60–70% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Pernau | July 1710 – late 1710 | 3,000 | 1,100–1,200 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[121] | ||

| 1710 | 1,700 | 65–70% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Reval (Tallinn) and suburbs | August 1710 – December 1710 | 9,801 | 6,000–7,646 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[122] | ||

| 1710 | 10,000 | 55–70% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Reval and surrounding places | 20,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[122] | ||||

| Stralsund | August 1710 – April 1711 | September 1710 – November 1710 | ~6,500–8,500 | 1,750–2,800 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[123] | |

| 1710 | ~7,000 | 25–40% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Stockholm | July/August 1710 – February 1711 | September 1710 – November 1710 | ~50,000–55,000 | 18,000–23,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[124] | |

| 1710 | ~55,000 | 33–40% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Visby | 1710–1711 | ~2,000–2,500 | 459–625 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[125] | ||

| 1711 | ~2,500 | 20–25% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Linköping | October 1710 – December 1711 | November 1710, July–August 1711 | ~1,500 | 386–500 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[126] | |

| Linköping and surrounding places | 1,772 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[126] | ||||

| Helsingør | November 1710 – summer 1711 | ~4,000 | 862 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[127] | ||

| Jönköping | Dec 1710-late 1711 | ~2,500 | 872–1,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[128] | ||

| Copenhagen | June 1711 – November 1711 | August – October 1711 | ~60,000 | 12,000–23,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[91] | |

| 1711 | ~60,000 | 20–35% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Ystad | June 1712 – late 1712 | ~1,600–2,300 | 750 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[129] | ||

| Malmö | June 1712 – late 1712 | August 1712 | ~5,000 | 1,500–2,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[130] | |

| 1712 | ~55,000 | 30–40% | Kroll (2006)[38] | |||

| Hamburg | 1712–1714 | August – October 1711 | ~70,000 | 9,000–10,000 | Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012)[131] | |

| 1713 | ~70,000 | 10–15% | Kroll (2006)[38] |

Habsburg Monarchy and Bavaria

[edit]From Poland, there had been three incursions of the plague into Silesia (then belonging to the Bohemian Crown within the Habsburg monarchy) in 1708: first into Georgenberg (Miasteczko), transmitted by a Kraków wagoner but successfully contained; then into Rosenberg (Olesno), where it killed 860 inhabitants out of 1,700;[132] and also into two villages near Militsch (Milicz), from where it spread into the nearby lands of Wartenberg (Syców).[133] After the Swedish defeat at Poltava in 1709, refugees from Poland including part of the Swedish-Polish corps of Joseph Potocki crossed into the Silesian borderlands, but also their Russian pursuers.[133] This resulted in the infection of 25 villages in the Oels (Oleśnica) and Militsch area, and while the plague seemed to have faded out by February 1710, it struck again and even more severe from spring 1710 to winter 1711, killing more than 3,000 inhabitants of Oels and many villagers.[133] In 1712, the plague crossed into Silesia for a last time from Polish Zduny, infecting the village of Luzin near Oels and killing 14 people before it vanished in the beginning of 1713.[133] Contemporary to the plague, there was also a cattle plague in Silesia.[133]

The plague also spread to other territories of the Habsburg monarchy, though it was not involved in the Great Northern War. Territories severely affected in 1713 were Bohemia (where 37,000 died only in Prague),[134] and Austria,[135] and the plague also struck Moravia and Hungary.[132]

From the Habsburg territories, the plague crossed into the Electorate of Bavaria, infecting in 1713 also the Free Imperial Cities of Free Imperial City of Nuremberg and Ratisbon[132] (Regensburg, then seat of the Perpetual Diet).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 13.

- ^ a b Byrne (2012), p. xxi.

- ^ Byrne (2012), p. xxii.

- ^ Byrne (2012), p. 322; for the Circum-Baltic Frandsen (2009), title and Kroll (2006), p. 139.

- ^ Sticker (1908), pp. 208–209.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frandsen (2009), p. 20.

- ^ Sticker (1908), pp. 209 ff.

- ^ Sticker (1908), pp. 210 ff.

- ^ a b c d Sticker (1908), p. 213.

- ^ Munzar (1995), p. 167.

- ^ O'Connor (2003), p. 19.

- ^ Lenke (1964), p. 3: "the winter of 1708/09 must have been the coldest hitherto known in Central Europe;" in detail pp. 27–35.

- ^ Frandsen (2006), p. 205.

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 273; Frandsen (2009), p. 20; details of the battle locations in Hatton (1968), pp. 183–184.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 20, 495; Sahm (1905), p. 35; Gottwald (1710), p. 1: "So wie mir berichtet worden/und ich von glaubwürdigen Leuten aus dem Lande selbst erfahren können [...]".

- ^ a b c Burchardt et al. (2009), p. 80.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 20; Burchardt et al. (2009), p. 82.

- ^ Burchardt et al. (2009), p. 82.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 25.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f Frandsen (2009), p. 33.

- ^ Sahm (1905), p. 35; Frandsen (2009), p. 33.

- ^ Sahm (1905), pp. 35–38.

- ^ detailed in Sahm (1905), p. 38; cf. Frandsen (2009), p. 33.

- ^ a b Sahm (1905), p. 38.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 38

- ^ a b c Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Danzig. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Frandsen (2009), p. 27.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 27, 31.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 26.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 28.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 34, Herden (2005), p. 66.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 35.

- ^ a b Herden (2005), p. 66.

- ^ a b Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Königsberg. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kroll (2006), p. 137.

- ^ a b c Frandsen (2009), p. 29.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 31.

- ^ a b c Kroll (2006), p. 138.

- ^ a b c d Kossert (2005), p. 96.

- ^ Kroll (2006), p. 138; Kossert (2005), p. 96.

- ^ Kossert (2005), p. 96: "Die Pest hatte leichte Beute, denn die körperliche Verfassung der bäuerlichen Bevölkerung war erbärmlich."

- ^ a b Kossert (2005), p. 107.

- ^ a b c Kossert (2005), p. 109.

- ^ Kossert (2005), pp. 104–110.

- ^ Jaeckel (1999), p. 14.

- ^ Jaeckel (1999), p. 15.

- ^ a b Jaeckel (1999), p. 16.

- ^ Jaeckel (1999), p. 18.

- ^ Schwartz (1901), pp. 53–79.

- ^ a b c Göse (2009), p. 165.

- ^ a b c d bei der Wieden (1999), p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Thiede (1849), p. 782.

- ^ Thiede (1849), pp. 781–782.

- ^ a b c Zapnik (2008), p. 228.

- ^ Englund (2002), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Schöning (1837), pp. 46–107, esp. pp. 68ff.

- ^ Schöning (1837), pp. 68ff, esp. p. 91.

- ^ Schöning (1837), p. 96.

- ^ bei der Wieden (1999), p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frandsen (2009), p. 41.

- ^ a b c d Frandsen (2009), p. 43.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 49.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 61.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 62.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 80; Engström (1994), p. 38.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 66–67.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Persson (2011), p. 21.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Svahn (retrieved 2012): Pesten i Jönköping. Archived 2010-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Vuorinen (2007), p. 55.

- ^ a b c Engström (1994), p. 38.

- ^ a b Bohn (1989), p. 83.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 72.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 74-76.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 79.

- ^ a b c Frandsen (2009), p. 80.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 107.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 135–138, Persson (2001), pp. 167–168.

- ^ a b Persson (2001), p. 168: "Det är därför svårt att avgöra om det i deras fall verkligen har rört sig om pest, även om förloppet i mina ögon verkar mycket suspekt."

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 138

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 140, 151.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 151.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 92.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 82.

- ^ a b Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Kopenhagen. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Frandsen (2009), p. 475.

- ^ a b c Frandsen (2009), p. 469

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 470

- ^ Persson (2011), pp. 3, 21–22.

- ^ For Gottorp and Stenbock, cf. Frandsen (2009), p. 475.

- ^ a b c d e Frandsen (2009), p. 483.

- ^ Winkle (1983), p. 4.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 476, Winkle (1983), p. 4.

- ^ Ulbricht (2004), pp. 271–272.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 476

- ^ Frandsen (2009), pp. 476, 483; Winkle (1983), p. 4.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 484.

- ^ a b c Winkle (1983), p. 5.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Ulbricht (2004), p. 300; Winkle (1983), p. 5: "300,000" thalers.

- ^ Winkle (1983), p. 6; Frandsen (2009), p. 480: "a quarter of a million."

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Ulbricht (2004), p. 300; Winkle (1983), p. 5.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Winkle (1983), pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Winkle (1983), p. 6.

- ^ a b Winkle (1983), p. 6.

- ^ a b Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Winkle (1983), p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Frandsen (2009), p. 480.

- ^ Winkle (1983), p. 7.

- ^ Frandsen (2009), p. 480; Winkle (1983), p. 8.

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Stettin. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Memel. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Tilsit. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Stargard. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Narva. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Riga. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Pernau. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Reval. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Stralsund. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Stockholm. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Visby. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Linköping. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Helsingør. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Jönköping. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Ystad. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Malmö. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kroll & Gabinsky (retrieved 2012): Hamburg. Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Lorinser (1837), p. 437

- ^ a b c d e Lorinser (1837), p. 438

- ^ Helleiner (1967), p. 60

- ^ Helleiner (1967), p. 60; Lorinser (1837), p. 437.

General references

[edit]- bei der Wieden, Brage (1999). Die Entwicklung der pommerschen Bevölkerung, 1701 bis 1918. Veröffentlichungen der Historischen Kommission für Pommern (vol. 33). Forschungen zur Pommerschen Geschichte (vol. 5). Cologne: Böhlau.

- Bohn, Robert (1989). Das Handelshaus Donner in Visby und der gotländische Aussenhandel im 18. Jahrhundert. Quellen und Darstellungen zur hansischen Geschichte. Vol. 33. Cologne: Böhlau.

- Burchardt, Jarosław; Meissner, Roman K; Burchardt, Dorota (2009). "Oddech śmierci – zaraza dżumy w Wielkopolsce i w Poznaniu w pierwszej połowie XVIII wieku" [Bubonic Plague – The Contagious Disease in the Great Poland and City of Poznań area in the first half of the XVIII c.] (PDF). Nowiny Lekarskie. 78 (1): 79–84.[permanent dead link]

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Death. Santa Barbara (CA): ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842531.

- Englund, Peter (2002). The Battle That Shook Europe – Poltava and the Birth of the Russian Empire. London: Tauris. ISBN 9781860648472.

- Engström, Nils Göran (1994). "Pesten i Finland 1710" [The plague in Finland in 1710]. Hippokrates. Suomen Lääketieteen Historian Seuran vuosikirja. 11: 38–46. PMID 11640321.

- Frandsen, Karl-Erik (2006). "'Das könnte nützen.' Krieg, Pest, Hunger und Not in Helsingør im Jahr 1711". In Stefan Kroll; Kersten Krüger (eds.). Städtesystem und Urbanisierung im Ostseeraum in der Frühen Neuzeit: Urbane Lebensräume und Historische Informationssysteme, Beiträge des wissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums in Rostock vom 15. und 16. November 2004. Geschichte und Wissenschaft. Vol. 12. Berlin: LIT. pp. 205–225. ISBN 9783825887780.

- Frandsen, Karl-Erik (2009). The Last Plague in the Baltic Region. 1709–1713. Copenhagen. ISBN 9788763507707.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frost, Robert I (2000). The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558–1721. Harlow: Longman.

- Göse, Frank (2009). "Prenzlau im Zeitalter des 'Absolutismus' (1648–1806)". In Neitmann, Klaus; Schich, Winfried (eds.). Geschichte der Stadt Prenzlau. Horb am Neckar: Geiger. pp. 140–184.

- Gottwald, Johann Christoph (1710). Memoriale Loimicum, Oder Kurtze Verzeichnüß, Dessen, Was in der Königl. Stadt Dantzig, bey der daselbst Anno 1709. hefftig graßirenden Seuche der Pestilentz, sich zugetragen, Nach einer Dreyfachen Nachricht, aus eigener Erfahrung auffgesetzet und beschrieben. Danzig. Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- Hatton, Ragnhild Marie (1968). Charles XII. of Sweden. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 9780297748267.

- Helleiner, Karl F. (1967). "The population of Europe from the Black Death to the Eve of the Vital Revolution". In Rich, E. E.; Wilson, C. H. (eds.). The Economy of Expanding Europe in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. The Cambridge Economic History of Europe from the Decline of the Roman Empire. Vol. 4. Cambridge: CUP. ISBN 9780521045070.

- Herden, Ralf Bernd (2005). Roter Hahn und Rotes Kreuz. Diskussionspapiere der Hochschule für öffentliche Verwaltung in Kehl. Kehl: BoD.

- Jaeckel, Gerhard (1999). Die Charité. Die Geschichte eines Weltzentrums der Medizin von 1710 bis zur Gegenwart. Berlin: Ullstein.

- Kossert, Andreas (2005). "Die Große Pest 1709–1711". Ostpreußen. Geschichte und Mythos. Berlin: Siedler. pp. 96 [101]–103 [108]. ISBN 9783641032326.

- Kossert, Andreas (2005). "Preußische Toleranz, Fremde und 'Repeuplirung'". Ostpreußen. Geschichte und Mythos. Berlin: Siedler. pp. 104 [109]–110 [115]. ISBN 9783641032326.

- Kroll, Stefan (2006). "Die "Pest" im Ostseeraum zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung". In Stefan Kroll; Kersten Krüger (eds.). Städtesystem und Urbanisierung im Ostseeraum in der Frühen Neuzeit: Urbane Lebensräume und Historische Informationssysteme, Beiträge des wissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums in Rostock vom 15. und 16. November 2004. Geschichte und Wissenschaft. Vol. 12. Berlin: LIT. pp. 124–148. ISBN 9783825887780.

- Kroll, Stefan; Grabinsky, Anne. "Städtesystem und Urbanisierung im Ostseeraum in der Neuzeit – Historisches Informationssystem und Analyse von Demografie, Wirtschaft und Baukultur im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert. B: Komplexe Historische Informationssysteme. B2: Der letzte Ausbruch der Pest im Ostseeraum zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts. Chronologie des Seuchenzugs und Bestandsaufnahme überlieferter Sterbeziffern. Karte". University of Rostock. Archived from the original on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

Suppages: Danzig Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Königsberg Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Stettin Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Memel Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Tilsit Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Narva Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Stargard Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Riga Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Pernau Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Reval Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Stralsund Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Stockholm Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Visby Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Linköping Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Jönköping Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Ystad Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Malmö Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Helsingør Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Kopenhagen Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine; Hamburg Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine - Persson, Bodil E. B. (2001). Pestens gåta. Farsoter i det tidiga 1700-talets Skåne. Studia historica Lundensia. Vol. 5. Lund: Historiska institutionen vid Lunds universitet.

- Lenke, Walter (1964). Untersuchung der ältesten Temperaturmessungen mit Hilfe des strengen Winters 1708–1709 (PDF). Berichte des Deutschen Wetterdienstes. Vol. 13, Nr. 92. Offenbach am Main.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Lorinser, Carl Ignaz (1837). "Die letzte Pest in Schlesien 1708–1713". Die Pest des Orients. Wie sie entsteht und verhütet wird. Berlin: Enslin. p. 437.

- Munzar, Jan (1995). "The "cold-wet" famines of the years 1695–1697 in Finland and manifestations of the Little Ice Age in Central Europe". In Heikinheimo, Pirkko (ed.). International conference on past, present and future climate. Helsinki: Edita. pp. 167–170.

- O’Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations. Westport, CT/London: Greenwood Press.

- Persson, Thomas (2011). "Pesten i Blekinge 1710–1711" (PDF). Blekinge museum.[permanent dead link]

- Sahm, Wilhelm (1905). Geschichte der Pest in Ostpreußen. Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schöning, Kurt von (1837). "Aktenmäßige Darstellung, wie ein Theil von Hinterpommern und die Provinz Neumark Brandenburg, als Gebiete eines neutralen Fürsten, während des Nordischen Krieges zweimal den unerlaubten Durchmarsch feindlicher Truppen erfuhren". Baltische Studien. 4 (1): 46–106.

- Schwartz, Paul (1901). "Die letzte Pest in der Neumark 1710". Schriften des Vereins für die Geschichte der Neumark. XI. Landsberg an der Warthe: 53–79.

- Sticker, Georg (1908). Die Pest. Abhandlungen aus der Seuchengeschichte und Seuchenlehre. Vol. 1. Gießen: A. Töpelmann (vormals J. Ricker).

- Svahn, Joakim. "Pesten i Jönköping". Jönköpings läns museum. Archived from the original on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2012-08-18.

- Thiede, Friedrich (1849). Chronik der Stadt Stettin. Bearbeitet nach Urkunden und den bewährten historischen Nachrichten. Stettin: Müller.

- Ulbricht, Otto (2004). Die leidige Seuche. Pest-Fälle in der Frühen Neuzeit. Cologne/Weimar: Böhlau.

- Vourinen, Heikki S. (2007). "History of plague epidemics in Finland" [Histoire des epidemies de peste en Finlande]. In Signoli, Michel; et al. (eds.). Peste: entre épidemies et sociétés. Firenze: Firenze University Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 9788884534903.

- Winkle, Stefan (1983). "Die Pest in Hamburg. Epidemiologische und ätiologische Überlegungen während und nach der letzten Pestepidemie im Hamburger Raum 1712/13" (PDF). Hamburger Ärzteblatt. 2–3/1983 (Sonderdruck of part I&II first published in Jg. 37 pp. 51–57 and 82–87): 1–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-20.

- Zapnik, Jörg (2006). "Pest in Stralsund während des Großen Nordischen Krieges 1710 bis 1711 und das Historische Informationssystem "PestStralsund1710"". In Stefan Kroll; Kersten Krüger (eds.). Städtesystem und Urbanisierung im Ostseeraum in der Frühen Neuzeit: Urbane Lebensräume und Historische Informationssysteme, Beiträge des wissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums in Rostock vom 15. und 16. November 2004. Geschichte und Wissenschaft. Vol. 12. Berlin: LIT. pp. 226–255. ISBN 9783825887780.

- Zapnik, Jörg (2007). Pest und Krieg im Ostseeraum. Der "Schwarze Tod" in Stralsund während des Großen Nordischen Krieges (1700–1721). Greifswalder Historische Studien. Vol. 7. Hamburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- 1700s disease outbreaks

- 1710s disease outbreaks

- 18th-century health disasters

- 1700s in Europe

- 1700s in the Holy Roman Empire

- 1700s in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- 1710s in Europe

- 1710s in the Holy Roman Empire

- 1710s in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- 18th-century disasters in Denmark

- 18th century in Estonia

- 18th century in Finland

- 18th century in Latvia

- 18th century in Prussia

- 18th century in Sweden

- 18th century in Ukraine

- 18th-century epidemics

- Great Northern War

- Health disasters in Europe

- History of Pomerania

- Second plague pandemic