List of volcanic eruptions in Iceland

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

This is an incomplete list of volcanic eruptions in Iceland.

Prehistoric eruptions

Dates are approximate.

- 16,000,000 years ago - the oldest known rock in Iceland was formed in a lava eruption. The age of the basaltic strata from west to east is 16–10 million years.[1][2] (See Geology of Iceland - Origins)

- Circa 3,200,000-1,800,000 years ago (Plio-Pleistocene) - Esjan (Esja) - The western part is about 3.2 million years and the eastern part is about 1.8 million years. The movements of the plate boundaries are continually moving the strata to the west and away from the active volcanic zone.[3] Two volcanoes were active in the Reykjavík region, Viðey volcano and Stardals volcano.[citation needed] They partially formed Esja (Esjan); the smaller mountains near Reykjavík; plus the islands and small peninsulas like Viðey and Kjalarnes.[3][4] (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 2,600,000-9,000 years ago - Viðey (caldera[citation needed]), at Reykjavík. The underwater eruption that formed Viðey island stopped circa 9,000 years ago. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 2,500,000-11,000 years ago. Grensdalur, currently dormant, inactive since the Pleistocene era. (Part of the West volcanic zone (WVZ))

- 2,500,000-11,000 years ago. Keilir was formed during a subglacial fissure eruption which thawed the ice and formed a subglacial lake, and caused explosive activity. Ice thickness and more exact time of eruption are not known, just that it took place during the Pleistocene (Weichselian).[5][6] (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- Circa 700,000 years ago- Snæfellsjökull stratovolcano on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula.[7] (Part of the Snæfellsnes volcanic belt (SVB))

- 400,000-500,000 years ago - Ingólfsfjall, The main volcanic bulk is about 400-500 000 years old.[8] (Part of the South Iceland Seismic Zone (SISZ))

- 100,000 years ago - Keilir, volcanic cone on the Reykjanes peninsula, in the Krýsuvík (volcanic system). (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 54,000 years ago - Tindfjallajökull, (stratovolcano), a 5 km (3.1 mi)-wide caldera was formed during Thórsmörk (ignimbrite) eruption.[9] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 42,000-12,400 years ago - Sveifluháls, volcanic melting of glacier ice induced the formation of one or more subglacial meltwater lakes. Dropping overburden pressures lead to the eruption of vitric phreatomagmatic tuff.[10]

- 11,000 years ago - Askja-S. Tephra found in Norway, Sweden, Northern Ireland, and Romania. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- Circa 10,600 years ago - Katla. It is thought that Katla is the source of more than 6 to 7 cubic kilometers (1.4 to 1.7 cu mi) of tephra[11][12][13][14] 'Vedde Ash' found at a number of sites including Vedde in Norway, Denmark, Scotland and North Atlantic cores.[15]

- Circa 9,500 BC Theistareykjarbunga (Þeistareykjarbunga). The first of three dated eruptions, produced approximately 18 billion cubic metres of basaltic lava.[16] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- circa 9,000 years ago - Skjaldbreiður lava shield formed in one huge and protracted eruption.[citation needed] The lava flowed south and formed the basin of Þingvallavatn, Iceland's largest lake.

- 8230 BC - Grímsvötn The eruption was VEI 6, producing some 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of tephra, resulting in the Saksunarvatn tephra.[17][18] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 6,800 BC Theistareykjarbunga (Þeistareykjarbunga). The second of three dated eruptions.[16] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 6700 BC. - the "Great Þjórsá Lava flow", the largest known effusive eruption in Iceland in the last 10,000 years, originated from the Veiðivötn (is:Veiðivötn) area.[19] The Þjórsá lava field is up to 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) in area and flowed over 100 km (62 mi) to the sea and forms the coast between Þjórsá and Ölfusá.[20][21] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 5,800 BC - Hveravellir? The Kjalhraun (hraun means "lava field") lava field is about 7,800 years old.[22]

- 5000 BC - Hekla (H5). The first acidic eruption in Hekla. The ash layer H5 is found in soil in the central highlands and in many parts of the North. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 6,800 BC Theistareykjarbunga (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 6000 BP - The Stórhöfði peninsula was formed to the south of Helgafell on the island of Heimaey.[23]

- 5000 BP - Bláfjöll Volcanic System, lava flow reached Reykjavík 20 km (12 mi) west. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 5000 BP - (or circa 3,000 BC - unsourced, see below) - Helgafell formed from a secondary eruption on the Stórhöfði peninsula.[24][23]

- 3,900 BC - Hekla H-Sv[25][26]

- 3500 BC - Grímsnes, VEI 3. The Grímsneshraun lava-fields in the area cover a total of 54 km2 (21 sq mi). The total volume of lava produced in the lava flows of Grímsnes has been estimated at 1.2 cubic kilometres (0.29 cu mi). (Part of the South Iceland Seismic Zone (SISZ))

- 5200 BP - Leitin, a Holocene, effusive eruption, shield volcano on the Reykjanes peninsula, 25 km (16 mi) south of Reykjavík. Part of the Brennisteinsfjöll volcanic system and therefore of the Reykjanes Volcanic Belt.[27][28] (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 3000 BC - Vestmannaeyjar (Westman Islands). Formation of Helgafell and the older lava on Heimaey.

- 2500 BC - Hekla (H4). (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1200 BC - Veiðivatnasvæði, Búrfellshraun flowed from a series of craters near Veiðivötn (is:Veiðivötn), on the one hand to Þórisós and on the other hand down with Tungná and Þjórsá all the way down to Landsveit

- 1000 BC - Katla. Two ash layers in the South and the Reykjanes peninsula. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 1,000-900 BC - Hekla (H3) is considered the most severe eruption of Hekla during the Holocene. which threw about 7.3 cubic kilometres (1.8 cu mi) of volcanic rock into the atmosphere, placing its Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) at 5. This would have cooled temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere for several years afterwards. Traces have been identified in Scottish peat bogs, and dendrochronology shows a decade of negligible tree ring growth in Ireland.[29][30][31][32] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 900 BC Theistareykjarbunga (Þeistareykjarbunga). The third of three dated eruptions.[16] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 800 BC (± 300 years) - Fremrinámur.[33] It is at the junction of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Greenland–Iceland–Faeroe Ridge.[34] It is one of five volcanic systems found in the axial rift zone in north east Iceland.[35] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- circa 500 BC - Hverfjall (Hverfell) is a tephra cone or Phreatomagmatic eruption in northern Iceland. The eruption was in the southern part of the Krafla fissure swarm.[36] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 400 BC Stóra-Eldborg undir Geitahlíð (Eldborgir) erupted, and the lava flowed 2,5 km to the sea.[37][38]

- 300 BC Mývatn, large fissure eruption pouring out basaltic lava. The lava flowed down the valley Laxárdalur to the lowland plain of Aðaldalur where it entered the Arctic Ocean about 50 km (31 mi) away from Mývatn. The crater row that was formed on top of the eruptive fissure is called Þrengslaborgir (or Lúdentarborgir). (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 150 AD ± 75 years[7] - Hengill, Shield volcano (Part of the West volcanic zone (WVZ))

- 200 AD ± 150 years - Snæfellsjökull stratovolcano on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula. There were several holocene eruptions,[7] of which the latest explosive eruption produced approximately 0.11 cubic kilometres (0.026 cu mi).[39][40] (Part of the Snæfellsnes volcanic belt (SVB))

9th century

Dates are approximate. (Note: First Norse settlers arrived in 870/874.)

- circa 800 - Vatnafjöll. a 40 km (25 mi) long, 9 km (6 mi) wide basaltic fissure vent system. It is part of the same system as Hekla. More than two dozen eruptions have occurred at Vatnafjöll during the Holocene Epoch.[41] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- circa 870 - Torfajökull. A stratovolcano, caldera and complex of subglacial volcanoes. The largest area of silicic extrusive rocks in Iceland.[42] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 870 - Ash and lava eruptions in Vatnaöldur. The craters resulted from 65 kilometres (40 mi) (or 42 kilometres (26 mi)[41]) long volcanic fissures within the area of a lake. The mainly explosive eruptions emitted 5–10 km3 (1.2–2.4 cu mi) of tholeiite basalt.[43][44] (It is part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

10th century

- 900 - Afstapahraun (is: Afstapahraun). (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 900 - Vatnajökull (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 900 - Krafla (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 900 - Hallmundarhraun (is: Hallmundarhraun) lava flows. [45][46]

- 900 - Rauðhálsahraun in Hnappadalur (is: Hnappadalur)

- 905 - Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 920 - Reykjanes, location uncertain, but tuff layer from the eruption is known. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 920 - Katla (ash layer called Katla-R). (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 934 (or 939) - Katla and Eldgjá: VEI 6. A large lava flow from Eldgjá flowed over Álftaver (is: Álftaver), Meðalland and Landbrot (is: Landbrot). The eruption was the largest flood basalt in historic time (800 square kilometres (310 sq mi),[47] 18 cubic kilometres (4.3 cu mi) of magma.[48])[49][50] Evidence from tree rings in the Northern Hemisphere indicates that 940 was one of the coolest summers in 1500 years. Summer average temperatures in Central Europe, Scandinavia, Canada, Alaska, and Central Asia were 2 °C lower than normal.[51] Probably the earthquake from which Molda-Gnúpur and his people fled according to "Settlement". Landnáma also tells about the formation of Sólheimasandur (:is: Sólheimasandur]]) in the great course of the Jökulsá river. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 940 - Vatnajökull / Veiðivötn (is:Veiðivötn) (volcanic layer in NA-land[clarification needed]) (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 999 or 1000 - Svínahraun (lava)

- 1000 - Katla. A tuff layer survives. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- Circa 1,000 - Hveravellir. A volcanic system in the Arnarvatnsheiði. The craters of this system produced the lava field Hallmundarhraun which extends some 50 kilometres (31 mi) westward into the valley of the Hvítá.[52]

11th century

- circa 1060 - Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

12th century

- 1104 - Hekla (H1). Its first and greatest eruption in historical time. Heavy ash fall to the north and northeast. Þjórsárdalur was destroyed, incl. the town of Stöng (Þjóðveldisbærinn Stöng) (is: Stöng (bær)). (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1151-1188 Krýsuvík fires (is: Krýsuvíkureldar). Volcanic activity in a fissure swarm known as Krýsuvík on the Reykjanes peninsula. Eruption in Trölladyngja; Ögmundarhraun and Kapelluhraun.[53] (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1158 - Hekla, second eruption. A VEI 4 eruption began on 19 January 1158 producing over 0.15 km3 of lava and 0.2 km3 of tephra. It is likely to be the source of the Efrahvolshraun lava on Hekla's west.[54][55] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- circa 1160 - ? in Vatnajökull (Vatnajökli). (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1160-1180 - Two eruptions in the sea off Reykjanes (ash layer known). (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1179 - Katla. Sources are unclear, but ash layers found in Greenland Glaciers. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1188 - ? Rjúpnadyngju lava flow and Mávahlíða lava flow. Rjúpnadyngjuhraun og Mávahlíðahraun runnu

13th century

- 1206 - Hekla, eruption number 3. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1210-1211 - from Reykjanes. Eldey formed. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1222 - Hekla, eruption number 4. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1223 - off Reykjanes, location uncertain. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1225 - off Reykjanes, location uncertain. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1226-1227 - some eruptions in Reykjanes. They are owned[clarification needed] by Yngra Stampahraun, (Klofningahraun), Eldvarpahraun, Illahraun and Arnarseturshraun. Sandy winter due to a large ash eruption at Reykjanestá and the so-called Medieval Valley fell. Hardness as a result. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1231 - off Reykjanes, location uncertain. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1238 - off Reykjanes, location uncertain. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1240 - off Reykjanes, location uncertain. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1245 - Katla. Fire and lava from Sólheimajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1262 - Katla. Fire with heavy ash fall in Sólheimajökull. The last people at Sólheimasandur (is: Sólheimasandur). (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1300-1301 - Hekla, eruption number 5. Heavy ash fall in Skagafjörður and famine as a result.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

14th century

- 1311 - Katla. Darkness in the Eastfjords and ash fall in many parts of the country. Major lava flow, probably on Mýrdalssandur, but sources are unclear and contradictory. Crop and hay failure the following year with associated casualties. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1332 - in Vatnajökull (Vatnajökli), probably in Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1340 - ? Brennisteinsfjöll (no lava from the 14th century known on the Reykjanes peninsula). (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1341 - Hekla, eruption number 6. The ash spread west through Borgarfjörður and Akranes. Great death, especially in Rangárvellir (is: Rangárvellir) and many settlements were destroyed. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1341 - ? Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1341 - (± 1 year) Brennisteinsfjöll, a VEI-2 eruption.[56] One of the bigger lava flows, runs south to the coast at Herdísarvík bay forming lava falls on their way.[57]

- 1354 - ? Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1357 - Katla. Extensive eruption and damage. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1362 - Knappafellsjökull. The largest ash eruption in Icelandic history. Litla-Hérað (Öræfasveit) was completely destroyed and few seem to have escaped. The group was called Öræfi when it started to rebuild and the glacier Öræfajökull. Most of the ash was carried east to the sea, but destroyed much of Hornafjörður and Lónshverfi along the way. Jökulhlaup to Skeiðarársandur and out to sea. (Part of the Öræfajökull volcanic belt (OVB))

- 1372 - north-west of Grímseyjar

- 1389-1390 - in and around Hekla, eruption number 7. Norðurhraun lava flows, Skarð, Tjaldastaðir and maybe more towns are subsumed.[53] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

15th century

- 1416 - Katla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1422 - off Reykjanes an island is formed and lasts for several years. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1440 - Hekla or surroundings. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1477 - Torfajökull. A stratovolcano, caldera and complex of subglacial volcanoes. The largest area of silicic extrusive rocks in Iceland.[42] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1477 - Landmannalaugar in the Highlands of Iceland.[58] It is at the edge of Laugahraun lava field, which was formed around 1477.[59] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1477 - at Heljargjárrein. Eruption on a long fissure in Veiðivötn (is:Veiðivötn) west of Vatnajökull.

- circa 1480- 1500 - Katla.[53] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- about 1500 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

16th century

- 1510 - Hekla eruption number 8. A large eruption with heavy ash fall to the south. The largest Hekla lava field from historical times. Extensive land degradation in Rangárvallasýsla as a result. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1554 - Vondubjallar southwest of Hekla. The eruption lasted for 6 weeks in the spring. Red bells formed and from them flowed Pálssteinshraun. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1580 - Katla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- circa 1582 - at Eldey

- 1597 - Hekla, eruption number 9. From January 3 into the summer. Volcanic eruptions were widespread but caused little living space, although mainly in Mýrdalur. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1598 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

17th century

- 1603 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1612 - Katla (and / or Eyjafjallajökull). The eruption began on October 16, but sources do not agree on which glacier erupted, Katla is considered more likely.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1619 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1625 - Katla. September 2–14 . Large eruption with heavy ash fall to the east. 25 towns were deserted. Þorsteinn Magnússon, abbot of Þykkvabær, wrote a report on the eruption, the first of its kind in Iceland. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1629 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1636-37 - Hekla, eruption number 10 began on May 8 and lasted for over a year. Ash fall to the northeast and little damage. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1637-38 - by the Westman Islands

- 1638 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1655 -? probably an eruption in Vatnajökull, probably in Kverkfjöll. Big lava flow in Jökulsá á Fjöllum.

- 1659 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1660-61 - Katla. The eruption began on November 3 and lasted until the end of the year. A small ash fall but a large flow on Mýrdalssandur and cut Höfðabrekka off. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1681 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1684-85 - Grímsvötn. A major lava flow in Jökulsá á Fjöllum, one person died and a number of livestock.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1693 - Hekla, eruption number 11 began on 13 February and lasted until the autumn. Heavy ash fall to the northwest at the beginning of the eruption which caused great and permanent damage in the surrounding areas. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1693 - Katla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1697 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

18th century

- 1702 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1706 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1711-12 - Kverkfjöll

- 1716 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1717 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1721 - Katla. Heavy ash fall, about 1 km3 (0.24 cu mi) and a big lava flow. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1724-29 - Mývatnseldar (is:Mývatnseldar) (Myvatn Fires, Krafla Fires). Lava flowed into Lake Mývatn and the volcanic "Viti crater" (Hell crater) formed by Krafla volcano.[60] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1725 - in Vatnajökull

- 1725 - southeast of Hekla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1726 - in Vatnajökull

- 1727 - Öræfajökull, at the glacier roots above Sandfellsskerji. 3 died. (Part of the Öræfajökull volcanic belt (OVB))

- 1729 - Kverkfjöll

- 1746 - Mývatnseldar, (is:Mývatnseldar), (Myvatn Fires, Krafla Fires). 1 eruption. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1753 - southwest of Grímsvatn

- 1755-56 - Katla. The eruption began on October 17 and lasted until mid-February. A large amount of ash, about 1.5 km3 (0.36 cu mi), reached the northeast and caused great damage in Skaftártunga, Álftaveri and Síða. A big lava flow on Mýrdalssandur, mostly west of Hafursey. Lightning killed two people. About 50 towns were deserted, most of them only temporarily. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1766 - west of Vatnajökull, probably in Bárðarbunga. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1766-68 - Hekla, eruption number 12. The largest lava eruption of Hekla in historical time. Ash fall in Húnavatns- and Skagafjarðarsýsla counties. 10 lands were deserted. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1774 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1783 - Nýey. Reykjaneshrygg, southwest of Eldey. The island of Nýey rose from the sea with intense, poisonous, sulphurous smoke, but disappeared in less than a year.[61] (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1783-84 Laki. ( Skaftáreldar, Grímsvötn, Þórðarhyrna, sometimes referred to in Icelandic as the Skaftáreldur, Skaftá Fires)[62] Lava flowed along Skaftá river valley and Hverfisfljót, down into the lowlands and covered about 580 km2 (220 sq mi) (including a gorge thought to have been 200 metres (660 ft) deep).[63] The eruption has been estimated to have killed over six million people globally. Ash fall and poisoning caused hay failure leading to a famine that killed about 25% of the island's population[64] and resulted in a drop in global temperatures, as sulfur dioxide was spewed into the Northern Hemisphere. This caused crop failures in Europe and may have caused droughts in India.[65] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1797 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

19th century

- 1807 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1816 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1821 - Katla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1821-23 - Eyjafjallajökull. The eruption began weakly on December 19, no lava flowed but some ash fell. Subsequently, Lava flowed north to Markarfljót. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1823 - Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1830 - Eldeyjarboði. Submarine eruption. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

- 1838 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1845-46 - Hekla, eruption number 13 began on September 2 and lasted for about 7 months. Heavy ash fall to the southeast and a lava flow in Ytri-Rangá. Lava flowed west and northwest, about 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi), so the town of Næfurholt had to be relocated. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1854 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1860 - Katla. A small eruption. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1861 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1862-64 - at Heljargjárrein. The eruption began on June 30 in a 15 km (9.3 mi) long fissure north of Tungnaárjökull. Trollagígar formed there and Tröllahraun flowed from them.

- 1867 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1867-68 - Mánáreyjar. Submarine eruption.

- 1872 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1873 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1874 - Askja. Likely eruption in February. Gas was seen. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1875 - Askja. Lava eruption began on January 3 . Sigketill began to form later that month. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1875 - Askja. A lava eruption began in Sveinagjá in Mývatnsöræf on 18 February on a 25 km (16 mi) long fissure. It lasted until mid-August and flowed from Nýjahraun. It is believed to be a magma flow from Askja. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1875 - Askja One of the largest ash eruptions in Icelandic history began on March 28 and lasted for about eight hours. Eruption from Víti and other craters. Heavy damage from ash fall in the middle of East Iceland and many towns were deserted. Many East Fjord people moved to the West as a result. Öskjuvatn was formed and it grew steadily. Eruptions occurred for several months. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1876 - Askja. The last flame was seen at the end of the year. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1876 - in Vatnajökull. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1878 - Krakatindur east of Hekla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1879 - Geirfuglasker. Submarine eruption.

- 1883 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1884 - Near Eldey. Submarine eruption. Unclear sources.

- ? 1885 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1887 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1889 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1892 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1896 - Probable eruption south of the Westman Islands

- 1897 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

20th century

- 1902-04 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1905-06 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1908-09 - Grímsvötn. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1910 - Grímsvötn. Ashfall was observed in the east of the country from June to November.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1913 - Mundafell / Lambafit east of Hekla. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1918 - Katla. The eruption began on October 12 and ended on November 5 . The eruption reached a height of 14.3 km (8.9 mi) and caused considerable damage in Skaftártunga. There was a lot of lava flow on Mýrdalssandur. It extended the southern coast by 5 km (3.1 mi) due to laharic flood deposits. Its present dormancy is among the longest in known history.[66] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1921 - Askja. A small lava eruption. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1922 - Askja. A small lava eruption. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1922 - Grímsvötn. The eruption began at the end of September and ended within a month.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1923 - Askja. A small lava eruption. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1923 - Grímsvötn. Smágos.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1926 - Askja. Eruption in the summer. A small island formed in Öskjuvatn. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1926 - at Eldey. Turbulence in the sea for several hours.

- 1927 - Esjufjöll. A small eruption, a lava flow off Breiðamerkurjökull and a Jökulhlaup (literally "glacial run") a type of glacial outburst flood).[67] One person was killed. It is located at the SE part of the Vatnajökull icecap. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1929 - Askja (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1929 - Kverkfjöll. A fire was seen for a long time during the summer.

- 1933 - Grímsvötn. Smágos. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1934 - Grímsvötn. The eruption began at the end of March and lasted until mid-April.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1930s - Gjálp An eruption took place in the 1930s. It had also caused a Jökulhlaup (literally "glacial run") a type of glacial outburst flood), but at the time, science could not yet analyze the events. The eruption remained subglacial.[68] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1938 - Grímsvötn. An eruption north of the caldera but did not emerge from the glacier ice.. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1941 - Grímsvötn. Possible eruption. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1945 - Grímsvötn. Possible eruption. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1947- 48 - Hekla, eruption number 14 began on March 29 with an explosion. The plume reached a height of 30 km (19 mi) ash fall to the south over Fljótshlíð and Eyjafjöll. Heklugjá opened lengthwise, about 0.8 km3 (0.19 cu mi) of lava flowed, mostly to the west and southwest from Axlargígur. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1954 - Grímsvötn. Possible eruption. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1955 - Katla. Probably a small eruption under the glacier. A little lava. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1961 - Askja. Lava eruption began on October 26 on a 300 m long fissure and lasted until the end of November. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1963- 67 - Vestmannaeyjar : Surtsey rose from the sea on November 14 in an underwater eruption southwest of Geirfuglasker. Later, the islands Syrtlingur and Jólnir were formed but soon disappeared again.

- 1970 - Hekla, eruption number 15 began on May 5 in the southwestern part of Heklugjár and in Skjólkvíar north of the mountain. Considerable ash fall to NNV, all the way north to Húnavatnssýslur. In the mountain itself the activity stopped after a few days but in Skjólkvíar it erupted for about 2 months. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1973 - Eldfell, Westman Islands, VEI 3. A 1600 m long eruption fissure opens east of Heimaey on 23 January. About a third of the town was buried under lava, over 400 properties were destroyed. A volcano formed and Heimaey expanded to the east.[69]

- 1975 - Krafla fires, 1st eruption 20 December. Lava eruption from a short fissure at Leirhnjúkur.[70] Note: Mývatnseldar (is:Mývatnseldar), (Myvatn Fires, Krafla Fires), Lake Mývatn and the volcanic "Viti crater" (Hell crater) formed by Krafla.[60] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1977 - Krafla fires, 2nd eruption 27–29 April.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1977 - Krafla fires, 3rd eruption 8–9 September.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1980 - Krafla fires, 4th eruption 16 March.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1980 - Krafla fires, 5th eruption July 10–18.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1980- 81 - Hekla, eruption number 16 began on August 17 and lasted until the 20th . Ash spread to the north, lava flowed mostly to the west and north. The eruption resumed on April 9 of the following year and ended on April 16. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1980 - Krafla fires, 6th eruption, 18–23 October.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ)) (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1981 - Krafla fires, 7th eruption, 30 January - 4 February.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1981 - Krafla fires, 8th eruption, 18–23 November.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 1983 - Grímsvötn. A small eruption at the end of May. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- ? 1984 - Grímsvötn. Probably a small eruption. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1984 - Krafla fires, 9th eruption, 4–18 September.[70] (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- ? 1985 - Final ridge under Vatnajökull. Possible eruption. Gosórói on meters and sigg boilers in the glacier.

- 1991 - Hekla, eruption number 17 began on January 17 in the southern part of Heklugjár but soon subsided. One crater east of the mountain was active until March 17. A considerable amount of lava flowed on the south side of the mountain, but there was little ash fall. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1996 - 1996 eruption of Gjálp (Gjálpargosið / Bárðarbunga). An eruption began on 30 September in a 4–5 km (2.5–3.1 mi) fissure under a glacier between Bárðarbunga and Grímsvatn and lasted until 13 October. The seismic activity indicated a magma flow from Bárðarbunga. Melting water flowed to Grímsvatn and ran from there to Skeiðarársandur on 5 November. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 1998 - Grímsvötn. 18. - 28 December. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 2000 - Hekla, eruption number 18. February 26 - March 8. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

21st century

- 2004 - Grímsvötn. The eruption began on November 1. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 2010 - Eyjafjallajökull. The eruption began at Fimmvörðuháls on March 20. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 2010 - Eyjafjallajökull. The VEI 4 eruption began in Eyjafjallajökull on 14 April. (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 2011 - Grímsvötn. (2011 eruption of Grímsvötn), The Plinian eruption began on May 21 and caused major disruption to air travel in Northwestern Europe from 22–25 May 2011.[71] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

- 2014-15 - Holuhraun. The eruption began on August 29, 2014, and ended on February 28, 2015. (Part of the North volcanic zone (NVZ))

- 2021 - Fagradalsfjall. The eruption began in Geldingadalir valley on March 19 and the "Fagradalshraun" lava has since then flowed into Meradalir valley and Nátthagi valley. (Part of the Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ))

Summary

(For a detail description of the volcanic zones, see : Geological deformation of Iceland)

Volcanic zones and systems

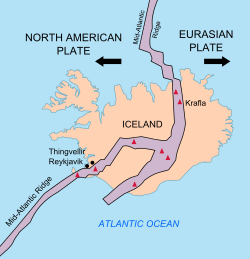

Iceland has several major volcanic zones surrounding the Iceland hotspot:

East volcanic zone (EVZ)

The East Volcanic Zone (EVZ), the central volcanoes Vonarskarð and Hágöngur, belong to the same volcanic system.[72]

Includes: Bárðarbunga, Bláhnjúkur, Brennisteinsalda, Eldgjá, Eyjafjallajökull, Gjálp, Grímsvötn, central volcano Hágöngur (is: Hágöngur), Hekla, Katla (volcano), Laki, Þjórsá Lava, Þórólfsfell, Surtsey, Thordarhyrna (Þórðarhyrna), Tindfjallajökull, Torfajökull, Vatnafjöll, Vatnajökull, Vatnaöldur, Vestmannaeyjar, central volcano Vonarskarð (is: Vonarskarð), Westman Islands,

Mid-Iceland Belt (MIB)

The Mid-Iceland Belt (MIB) connects the East, West and North volcanic zones, across central Iceland.

North volcanic zone (NVZ)

North of Iceland, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge is called Kolbeinsey Ridge (KR) and is connected to the North Volcanic Zone via the Tjörnes Fracture Zone (TFZ).

Includes: Askja, Dettifoss, Dimmuborgir, Fremrinámur, Grjótagjá, Herðubreið, Hverfjall, Jökulsá á Fjöllum, Kollóttadyngja, Krafla, Kverkfjöll, Mývatn, Öskjuvatn, Rauðhólar, Theistareykjarbunga, Trölladyngja

Öræfajökull volcanic belt (ÖVB)

The Öræfajökull volcanic belt (ÖVB) is an intraplate volcanic belt, connected to the Eurasian plate.[73][74]

Includes: Knappafellsjökull, Öræfasveit, Öræfajökull

Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ)

The Reykjanes volcanic zone (RVZ) is one of two major and active transform faults zones striking west-northwest in northern and southern Iceland. Two large fracture zones, associated with the transform faults, namely Tjörnes and Reykjanes Fracture Zones are found striking about 75°N to 80°W.[75][76]

- the Reykjanes Ridge (RR) (the Mid-Atlantic Ridge south of Iceland)

- the Reykjanes Volcanic Belt (RVB) (on the main island)

Includes: Bláfjöll, Brennisteinsfjöll, Búrfell (Hafnarfjörður), Eldborg í Bláfjöllum, Fagradalsfjall, Heiðin há, Helgafell (Hafnarfjörður), Hengill, Keilir, Krýsuvík (volcanic system), Krýsuvík fires, Leitin, Rauðhólar (Reykjavík), Stóra-Eldborg undir Geitahlíð, Svartsengi Power Station, Sveifluháls, Vífilsfell, Þorbjörn (mountain)

Snæfellsnes volcanic belt (SVB)

The Snæfellsnes volcanic belt (SVB) is an intraplate volcanic belt, connected to the North American plate.[73]

It is proposed that the east-west line from the Grímsvötn volcano in the Mid-Iceland Belt (MIB) to the SVB shows the movement of the North American Plate over the Iceland hotspot.[77]

Includes: Arnarstapi, Djúpalónssandur, Grundarfjörður, Hellnar, Ljósufjöll, Lóndrangar, Snæfellsjökull

South Iceland Seismic Zone (SISZ)

The South Iceland Seismic Zone (SISZ) is a fracture zone, which connects the East and West Volcanic Zones. It contains its own volcanic systems, smaller than those in the Mid-Iceland Belt.

Includes: Grímsnes, Ingólfsfjall, Kerið, Reynisdrangar, Selfoss (town)

Tjörnes Fracture Zone (TFZ)

The Tjörnes Fracture Zone (TFZ) connects the North Volcanic Zone to the Kolbeinsey Ridge (KR), which is part of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It contains its own volcanic systems, which are smaller than those in the Mid-Iceland Belt.

It is one of two major and active transform faults zones striking west-northwest in northern and southern Iceland.[75] The Tjörnes and Reykjanes Fracture Zones are found striking about 75°N to 80°W.[76]

West volcanic zone (WVZ)

Includes: Barnafossar, Geitlandsjökull, Geysir, Hengill, Hlöðufell, Hraunfossar, Hveravellir, Kjölur, Langjökull, Ok (volcano), Prestahnúkur, Skjaldbreiður, Stóra-Björnsfell, Surtshellir, Víðgelmir, Þórisjökull, plus Skríðufell, Fjallkirkja, Þursaborg, and Péturshorn.[78]

Eruptive activity

Grímsvötn, including the Skaftá eruption of 1783, is probably the most eruptive volcano system. The Lakagígar lava field alone is estimated to have produced about 15 cubic kilometres (3.6 cu mi) of lava. Grímsvötn has probably had more than 30 eruptions in the last 400 years, and produced around 55 cubic kilometres (13 cu mi) over the last 10,000 years.[79] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

Katla has erupted 17 times in historical times, and Eldgjá seems to be part of the same system. The total volume of volcanic eruptions from Katla over the last 10,000 years is very similar to Grímsvötn.[79] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

Hekla has erupted at least 17 times in historical times, with total volume about 7 cubic kilometres (1.7 cu mi), but around 42 cubic kilometres (10 cu mi) since the last ice age.[79] (Part of the East volcanic zone (EVZ))

See also

- Lists of volcanoes

- Volcanism of Iceland

- Geology of Iceland

- List of volcanoes in Iceland

- Geological deformation of Iceland

- Global Volcanism Program

References

- ^ Müller, R. Dietmar; Royer, Jean-Yves; Lawver, Lawrence A. (1993-03-01). "Revised plate motions relative to the hotspots from combined Atlantic and Indian Ocean hotspot tracks". Geology. 21 (3): 275. Bibcode:1993Geo....21..275D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1993)021<0275:rpmrtt>2.3.co;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ^ Denk, Thomas; Grímsson, Friðgeir; Zetter, Reinhard; Símonarson, Leifur (2011-02-23), Introduction to the Nature and Geology of Iceland, 35, retrieved 2018-10-16

- ^ a b Hvernig myndaðist Esjan? Vísindavefurinn, 9 December 2008 (in Icelandic)

- ^ Freyr Pálsson: Jarðfræði Reykjavíkursvæðisins. Háskóla Íslands, Raunvísindadeild, Jarð- og landfræðiskor. (2007)

- ^ Snæbjörn Guðmundsson: Vegavísir um jarðfræði Íslands. Reykjavík 2015, p. 22-23

- ^ Ari Trausti Guðmundsson, Pétur Þorsteinsson: Íslensk fjöll. Gönguleiðir á 152 tind. Reykjavík 2004, p. 156-157

- ^ a b c "Hengill". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Snæbjörn Gudmunðsson: Vegvísir um jarðfræði Íslands. Reykjavík 2015, p. 257

- ^ "Tindfjallajökull". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Emily Constantine Mercurio: Processes, Products and Depositional Environments of Ice-Confined Basaltic Fissure Eruptions: A Case Study of the Sveifluháls Volcanic Complex, SW Iceland. University of Pittsburgh. (2011) Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ "Katla Volcano". Institute of Earth Sciences. University of Iceland. Archived from the original on 9 November 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Mangerud, J., Lie, S.V., Furned, H., Kristiansen, I.L., Lømo, L. (1984) A Younger Dryas Ash Bed in Western Norway, and Its Possible Correlations with Tephra in Cores from the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic. Quaternary Research 21 85–104

- ^ Grönvold, K.; Oskarsson N.; Johnsen S.J.; Clausen H.B.; Hammer C.U.; Bond G.; Bard E. (1995). "Ash layers from Iceland in the Greenland GRIP ice core correlated with oceanic and land sediments". Earth Planet Sci Lett. 135 (1–4): 149–155. Bibcode:1995E&PSL.135..149G. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(95)00145-3.

- ^ Árni Hjartarson (2003), "Postglacial Lava Production in Iceland" (PDF), in Árni Hjartarson (ed.), PhD-thesis, Geological Museum, University of Copenhagen, pp. 95–108[dead link]

- ^ Housley, R. A.; Lane, C. S.; Cullen, V. L.; Weber, M. -J.; Riede, F.; Gamble, C. S.; Brock, F. (2012-03-01). "Icelandic volcanic ash from the Late-glacial open-air archaeological site of Ahrenshöft LA 58 D, North Germany". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (3): 708–716. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.11.003.

- ^ a b c "Global Volcanism Program".

- ^ "Holocene Volcano List". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Grímsvötn". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Smithsonian Institution - Global Volcanism Program: Worldwide Holocene Volcano and Eruption Information". Volcano.si.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-26. Retrieved 2015-12-16.

- ^ Árni Hjartarson 1988: „Þjórsárhraunið mikla - stærsta nútímahraun jarðar“. Náttúrufræðingurinn 58: 1-16.

- ^ Árni Hjartarson 1994: „Environmental changes in Iceland following the Great Þjórsá Lava Eruption 7800 14C years BP“. In: J. Stötter og F. Wilhelm (ed.) Environmental Change in Iceland (Munchen): 147-155.

- ^ "Global Volcanism Program – Hveravellir". si.edu. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ^ a b US Geological Survey

- ^ visitvestmannislands.is

- ^ Guðrún Sverrisdóttir; Níels Óskarsson; Árný E. Sveinbjörnsdóttir; Rósa Ólafsdóttir. "The Selsund Pumice and the old Hekla crater" (PDF). Institute of earth sciences, Reykjavik. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Elsa G. Vilmundardóttir og Árni Hjartarson 1985: Vikurhlaup í Heklugosum. Náttúrufræðingurinn 54, 17-30.

- ^ Kristján Sæmundsson, Magnús Á. Sigurgeirsson, Árni Hjartarson, Ingibjörg Kaldal, Sigurður Garðar Kristinsson and Skúli Víkingsson (2016). Geological Map of Southwest Iceland, 1:100.000 (2nd ed.). Reykjavík: Iceland GeoSurvey.

- ^ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskuldsson: Iceland. Classic geology of Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p.56

- ^ Eríksson, Jón; et al. (2000). "Chronology of late Holocene climatic events in the northern North Atlantic based on AMS 14C dates and tephra markers from the volcano Hekla, Iceland". Journal of Quaternary Science. 15 (6): 573–580. Bibcode:2000JQS....15..573E. doi:10.1002/1099-1417(200009)15:6<573::AID-JQS554>3.0.CO;2-A. Archived from the original on 2012-12-17.

- ^ "Hekla". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2005). Iron Age Communities in Britain (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 256. ISBN 0-415-34779-3.Pg 68

- ^ "Hekla". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "List of Icelandic Volcanoes". Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ "Geology". Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ "Geothermal Projects in NE Iceland at Krafla, Bjarnarflag, Gjástykki and Theistareykir" (PDF). p. 13. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ^ The Hverfjall fissure eruption Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 29 October 2008

- ^ Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , p.112 - 117

- ^ Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga of sérkenni. Reykjavík 1989, p. 45

- ^ "Snaefellsjökull: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ Rosi, Mauro; Luip, Luca; Papale, Paolo; Stoppato, Marco (2003). Volcanoes (A Firefly Guide). Firefly Books. pp. 130, 131. ISBN 978-1-55297-683-8.

- ^ a b Global Volcanism Program: Vatnafjöll

- ^ a b C.F. Zellmer, et al.: On the recent bimodal magmatic processes and their rates in the Torfajökull–Veidivötn area, Iceland. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 269 (2008) 387–397.

- ^ G. Larsen, Thor Thordarson: Phreatomagmatism in the Eastern Volcanic Zone; 25 July 2010

- ^ Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program - Vatnaöldur

- ^ Árni Hjartarson 2014. Hallmundarkviða, eldforn lýsing á eldgosi. Náttúrufræðingurinn 84 (1–2). 27–37.

- ^ Árni Hjartarson 2015. Hallmundarkviða. Áhrif eldgoss á mannlíf og byggð í Borgarfirði. Náttúrufræðingurinn 85, 60-67.

- ^ Árni Hjartarson 2011. Víðáttumestu hraun Íslands. (The Largest Lavas of Iceland). Náttúrufræðingurinn 81, 37-49.

- ^ "Katla: Eruptive History". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Albert Zijlstra (29 September 2016). "Eldgja: Eruption dating". Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ Oppenheime, Clive; et al. (19 March 2018). "The Eldgjá eruption: timing, long-range impacts and influence on the Christianisation of Iceland". Climatic Change. 147 (3–4): 369–381. doi:10.1007/s10584-018-2171-9. PMC 6560931. PMID 31258223.

- ^ "Volcanic eruption influenced Iceland's conversion to Christianity". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- ^ Sveinn Jakobson u.a., Volcanic systems and segmentation of the plate boundaries in S-W-Iceland

- ^ a b c Ferlir, Volcanic Eruptions in Historical Times

- ^ "Hekla". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Thorarinsson, p. 11

- ^ Brennisteinsfjoll, Global Volcanism Program, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga of sérkenni. Reykjavík 1989, p. 797

- ^ "Auglýsing um friðland að Fjallabaki". Stjórnartíðindi B, nr. 354/1979. August 13. 1979. Retrieved on August 21. 2014. (in Icelandic)

- ^ Sigurður Steinþórsson. "Í hvaða gosi myndaðist hraunið hjá Landmannalaugum og hvaða ár?". The Icelandic Web of Science July 4. 2008. Retrieved on 21 August 2014. (in Icelandic)

- ^ a b Krafla Visitor Centre, Myvatn Fires, Krafla Fires

- ^ University of Iceland, Earth Sciences, How common are new islands in eruptions? by Professor Sigurður Steinþórsson, 9 June 2005.

- ^ Th. Thordarson; S. Self (May 1993). "The Laki (Skaftár Fires) and Grímsvötn eruptions in 1783–1785". Bulletin of Volcanology (abstract). 55 (4): 233–63. doi:10.1007/BF00624353.

- ^ "Vatnajökull National Park—Lakagigar". Klaustur.is. Kirkjubæjarklaustur. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ Gunnar Karlsson (2000), Iceland's 1100 Years, p. 181

- ^ How The Earth Was Made: The Age of Earth (video), History.com

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 November 2005. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Ari Trausti Guðmundsson, Pétur Þorsteinsson: Íslensk fjöll. Gönguleiðir á 151 tind. Reykjavík 2004, p. 200.

- ^ Snæbjörn Guðmundsson: Vegavísir um jarðfræði Íslands. Reykjavík 2015, p. 280-281

- ^ Thorarinsson, S.; Steinthorsson, S.; Einarsson, T.; Kristmannsdottir, H.; Oskarsson, N. (1973-02-09). "The eruption on Heimaey, Iceland". Nature. 241 (5389): 372–375. Bibcode:1973Natur.241..372T. doi:10.1038/241372a0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Reykjavík Grapevine June 4 2021, The Message In The Magma: The Geldingadalir Eruption Site Is Growing—What Have We Learned? By Hannah Jane Cohen

- ^ Smithsonian Institution - Global Volcanism Program - Grimsvotn 2011

- ^ T. Gudmundsson; Thórdís Högnadóttir (January 2007). "Volcanic systems and calderas in the Vatnajökull region, central Iceland: Constraints on crustal structure from gravity data". Journal of Geodynamics. 43 (1): 153–169. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..153G. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.015.

- ^ a b T. Thordarson; G. Larsen (January 2007). "Volcanism in Iceland in historical time: volcano types, eruption styles and eruptive history". Journal of Geodynamics. 43 (1): 118–152. Bibcode:2007JGeo...43..118T. doi:10.1016/j.jog.2006.09.005.

- ^ H. Jóhannesson; K. Sæmundsson (1998). Geologic Map of Iceland, 1:500,000. Bedrock Geology. Reykjavík: Icelandic Institute of Natural History and Iceland Geodetic Survey.

- ^ a b Einarsson, P. (1991). "Earthquakes and present-day tectonism in Iceland". Tectonophysics. 189 (1–4): 261–279. doi:10.1016/0040-1951(91)90501-I.

- ^ a b Ward, P. L. (1971). "New Interpretation of the Geology of Iceland". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 82 (11): 2991–3012. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1971)82[2991:NIOTGO]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ W. Jason Morgan; Jason Phipps Morgan. Plate velocities in hotspot reference frame: electronic supplement (PDF). p. 111. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Kortabók Mál og Menningar, Reykjavík 2005, pp.48/49 and 55/56, icel.

- ^ a b c Visindavefur, Science Web, Which volcano has erupted the most? By Sigurður Steinþórsson, Professor Emeritus

External links

- Mountains of Iceland

- Stratovolcanoes of Iceland

- Active volcanoes

- VEI-5 volcanoes

- East Volcanic Zone of Iceland

- 19th-century volcanic events

- 20th-century volcanic events

- One-thousanders of Iceland

- Volcanic systems of Iceland

- Central volcanoes of Iceland

- 2021 earthquakes

- Krýsuvík Volcanic System

- Reykjanes Volcanic Belt

- Fissure vents

- Subglacial volcanoes of Iceland

- Volcanic eruptions in 2021

- Eyjafjallajökull

- Southern Region (Iceland)

- Calderas of Iceland