Lower gastrointestinal series

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2011) |

| Lower gastrointestinal series | |

|---|---|

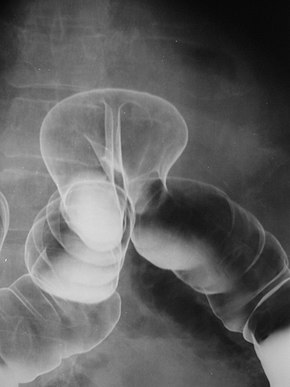

Radiograph of a barium enema displaying a colonic herniation. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 87.64 |

A lower gastrointestinal series is a medical procedure used to examine and diagnose problems with the human colon of the large intestine. Radiographs (X-ray pictures) are taken while barium sulfate, a radiocontrast agent, fills the colon via an enema through the rectum.

The term barium enema usually refers to a lower gastrointestinal series, although enteroclysis (an upper gastrointestinal series) is often called a small bowel barium enema.

Purpose

[edit]For any suspected large bowel disease, colonoscopy is the investigation of choice because tissue sample can be taken for investigation. Virtual colonoscopy (also known as CT colonography) is another preferred investigation, provided that facilities and expertise are available. Virtual colonoscopy also avoids the risk of total blockage of any stricture in the large bowel due to barium impaction.[1] Some conditions are absolutely contraindicated for barium enema namely: toxic megacolon, pseudomembranous colitis, and recent history rigid endoscopy of the large bowel in the past five days and recent history of flexible endoscopy in the past 24 hours. This is because, rigid endoscopy tends to use larger biopsy forceps to take tissue samples from the bowel wall while flexible endoscopy uses small biopsy forceps to take superficial samples.[1] For those with incomplete bowel preparation, the subject can return the next day or the day after next to repeat the procedure. If barium meal was performed recently, then it is advised to wait for another seven to ten days before repeating the procedure. Some frail subject may not be suitable for barium meal.[1]

Barium enemas are most commonly used to check bowel health; they can help diagnose and evaluate the extent of inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Polyps can be seen, though not removed during the exam like with a colonoscopy—they may be cancerous. Other problems such as diverticulosis (small pouches formed on the colon wall that can become inflamed) and intussusception can be found (and in certain cases the test itself can treat intussusception). An acute appendicitis or twisted loop of the bowel may also be seen. If the picture is normal a functional cause such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may be considered.

In a healthy colon, barium should fill the colon uniformly and show normal bowel contour, patency (should be freely open), and position.

Additional conditions under which the test may be performed:

- CMV gastroenteritis/colitis

- Hirschsprung's disease

- intestinal obstruction

- intussusception (children)

Procedure

[edit]

Barium enema can be done in two ways, namely double contrast and single contrast methods. Double contrast (where air is inflated into the bowel after excess barium are drained through anus) is useful in visualising mucosal pattern. For single contrast study (whole bowel is filled up with barium without inflating any air), it is used to visualise any obstruction in the large bowel, and it is used in children where visualisation of mucosal pattern is not needed. Barium enema is also used to reduce an intussusception where this disorder is more commonly found in children.[1] 500 ml of Polibar 150% (barium sulfate suspension) is used to perform this study. Subject should be fasted and Picolax (sodium picosulfate) is taken orally to empty the bowels before barium enema procedure.[1]

This test may be done in a hospital or clinic. The individual lies on the X-ray table and a preliminary X-ray is taken. The individual is then asked to lie on their side while a well lubricated enema tube is inserted into the rectum. As the enema enters the body, the individual might have the sensation that they need to have a bowel movement. The barium sulfate, a radiodense (shows as white on X-ray) contrast medium, flows through the rectum into the colon. A large balloon at the tip of the enema tube may be inflated to help keep the barium sulfate inside. The flow of the barium sulfate is monitored by the health care provider on an X-ray fluoroscope screen (like a TV monitor). Air may be puffed into the colon to distend it and provide better images (often called a "double-contrast" exam). If air is used, the enema tube will be reinserted if it had been removed and a small amount of air will be introduced into the colon, and more X-ray pictures are taken.

The individual is usually asked to move to different positions and the table is slightly tipped to get different views.

If there is a suspected bowel perforation, a water-soluble contrast agent (such as diatrizoate) is used instead of barium. The procedure is otherwise very similar, although the images will be of poorer quality. If a perforation exists, the contrast will leak from the bowel to the peritoneal cavity; water-soluble material is less obscuring compared to barium should an abdominal incision to remove the contrast be necessary.

Radiographic views

[edit]Assume that the x-ray tube is moving above the table and the x-ray film is moving below the table (overcouch):[1] The subject lying supine to give AP (anteroposterior) view of all the bowels.[1] Left lateral view of rectum is to view the rectum from lateral position.[1] Right anterior oblique (RAO) position is to view the caecum, ascending colon, right hepatic flexure and sigmoid colon without overlapping of other bowels.[1] Left anterior oblique (LAO) position is to view the splenic flexure without overlapping of other bowels.[1] Left posterior oblique (LPO) position is to view the sigmoid colon without overlapping of other bowels.[1] Hampton's view (prone caudal view) of rectosigmoid colon is taken when the subject is in prone position with the X-ray tube tilted towards the feet at 30 degrees. This is to separate out the loops of sigmoid colon.[2]

Other views include right and left decubitus views[1]

Risks

[edit]X-rays are monitored and regulated to provide the minimum amount of radiation exposure needed to produce the image. Most experts feel that the risk is low compared with the benefits. Pregnant women and children are more sensitive to the risks of ionizing radiation.

A more serious risk is a bowel perforation.

Special considerations

[edit]CT scans and ultrasounds are now the tests of choice for the initial evaluation of abdominal masses, and colonoscopies are becoming the standard for routine colon screening for those over age 50 or with a familial history of polyps or colon cancer, although it is not uncommon for a barium enema to be done after a colonoscopy for further evaluation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Watson N, Jones H (2018). Chapman and Nakielny's Guide to Radiological Procedures. Elsevier. pp. 60–63. ISBN 9780702071669.

- ^ Elizabeth, MU; Campling, Jo; Royle, AJ (9 November 2013). Radiographic Techniques and Image Evaluation. Springer. pp. 306–307. ISBN 9781489929976. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

External links

[edit]- Duplicated Colon on Barium Enema - MedPix Medical Image Database

- RadiologyInfo - The radiology information resource for patients: Barium Enema

- NIH page on barium enemas